Cross-Border Governance: Balancing Formalized and Less Formalized Co-Operations

Abstract

:1. Introduction and Research Questions

2. Cross-Border Governance in Europe

2.1. Cross Border Co-Operation in Western Europe

- The objective necessities for cross-border co-operation can be based on a common (not only comparable) problem, on prevention policies based on favorable situations and an alarmist agenda setting [17].

- In many cases cross-border activities are based on a cross-border homogeneity of preferences and interests which is mainly due to the influence of certain epistemic communities. These epistemic communities are often science based but with intensive linkages to the regional policy world. They can be extremely successful in generating cross-border pressure for actions. This kind of cross-border regime building is most of the time sectorally orientated (e.g., specific environmental issues) [17].

2.2. Governance Solutions for Cross-Border Co-Operations

2.3. Success Factors for Cross-Border Governance Systems

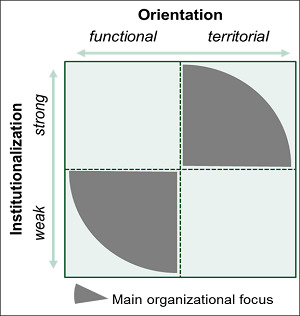

3. Theoretical Model of Cross-Border Governance

| Territorial orientation | Functional orientation | |

|---|---|---|

| Structural pattern of interaction | Vertical, hierarchical | Horizontal, network-based |

| Type of actors/members | Mainly public actors | Integration of private or societal actors, of thematic experts |

| Thematic scope | Broad, many different tasks | Narrow, focus on a specific task |

| Geographic scale | Congruent and stable boundaries (identical to administrative entities) | Fuzzy and variable boundaries depending on the specific issue |

| Strong | Weak | |

|---|---|---|

| Membership | closed, defined representatives | open, flexible |

| Legal form | defined legal status (public law) | loose network arrangements (private law) |

| Organizational structure | Existence of several bodies, complex | Simple structure, modest complexity |

| Decision-making | majority voting | consensus, unanimous votes |

| Character of decisions | binding character, mandatory | non-binding, without obligation |

| Political involvement | political as well as sectoral expertise | various experts, administration |

| Time perspective | Long term perspective | Short or medium term perspective |

4. Empirical Findings of Two Cross-Border Regions

4.1. The Lake Constance Region

- the “phase of formation” mainly due to the consequences of industrialization and with a strong focus on the utilization of the common good “Lake Constance”;

- the “post-war phase” trying to initiate exchange over national borders and to improve international communication;

- the “phase of environment” about the 1960s when severe conflicts between economic growth and protection of the environment (especially of the potable water of the lake) had to be solved;

- the “phase of regionalization” in the 1980s and 1990s driven by the efforts of local and regional actors to counterbalance the strengthening of the national level, bringing along the foundation of the spatial planning conference and the formulation of common guide lines for the development of the cross-border region;

- the “phase of Europeanization” showing an intensification of co-operative activities as well as the foundation of new cross-border institutions in parallel to European initiatives on cross-border integration;

- the “INTERREG-phase” with broad initiatives from all different sectors of society, and economy focusing on the financial support of the European Union (INTERREG programs).

- The International Lake Constance Conference (IBK—Internationale Bodenseekonferenz) is a collaborative association of the regions around the Lake Constance. It functions as a sort of umbrella organization for the different cross-border initiatives going on in the region. Its overall objective is to maintain and promote the Lake Constance region as an attractive living, natural, cultural and economic environment by means of political consultations and joint programs. The IBK was founded in 1972 and has adapted its agenda as well as its organizational settings over the last years. Today, the IBK is constituted by the Conference of the head of governments, a more operative committee of the highest representatives of the administrations, seven commissions (focusing on education, research and development, culture, environment, transport, health and social services as well as public relations) with specific working groups, as well as an executive management board.

- The INTERREG-program Alpine Rhine/Lake Constance/High Rhine (ABH) is supported by the European Union’s funding program for cross-border co-operations. For the new funding period (2014–2021) altogether about 80 million EUR from the European Union, the different regions, as well as from private actors, will probably be available for supporting different cross-border projects. The program aims to strengthen the regional competitiveness, innovation, employment and education. At the same time, environmental issues as well as questions concerning energy or transport will also be focused on. Different commissions and committees assure a high representation of the different authorities involved in the program.

4.2. The Upper Rhine Region

- the “post-war phase” characterized by a strong top-down intention to improve the international communication, especially across the border Germany and France, by some town-partnerships and by a couple of big projects like the airport Bale/Mulhouse;

- the “institution-building phase” in the seventies when the Upper-Rhine Conference was founded—based on an international agreement between France, Germany, and Switzerland—and has offered an institutional framework for the cross-border co-operations in the region;

- the “phase of intensification and diversification” till the year 2000 driven by the financial support of the INTERREG program of the European Union which increased the number of cross-border initiatives as well as the heterogeneity of the involved actors;

- the “phase of the Eurodistricts” which were created in the beginning of the 2000s as four different sub-areas of the Upper Rhine region and rescaled a great part of the regional cross-border activities to a much smaller perimeter;

- the “reform of the governance model” in the last decade which was driven by the creation of the Tri-National Metropolitan Region as coordinating and supporting body for the cross-border region.

- The tri-national Metropolitan Region Upper Rhine was founded in the year 2010. It aims at coordinating cross-border activities of the different policy fields internally by offering a synergetic network of four strategic pillars of the TMO work (policy and administration, economy, research and development, civil society). In addition, an external coordination shall also be assured in these relevant policy fields by taking a moderating role in the multilevel governance system and its vertical distribution of specific tasks. At the same time, actors from outside the administration sector shall be better integrated into the cross-border governance structures.

- The Upper Rhine Conference (more correctly, the Franco-German-Swiss Conference of the Upper Rhine) provides the traditional institutional framework for cross-border co-operation in the Upper Rhine region. It is the successor organization to the two regional commissions, which derived from the 1975 Upper Rhine agreement between Germany, France and Switzerland. It is composed by (i) a Steering Committee as the coordinating and decision-making body of the Upper Rhine Conference; (ii) a Plenary Assembly as a broad discussion forum, and (iii) the Joint Secretariat as the executive management body of the Upper Rhine Conference. In addition; (iv) twelve working groups have been established to deal with cross-border issues that fall within the remit of the Upper Rhine Conference.

5. Different Ways of Organizing Cross-Border Governance

Comparison of the Two Case Regions

- Geographic scale: Cross-border governance in the Upper Rhine region is characterized by geography of a pyramidal structure of scales and subscales. Co-operations on subscales take an important role (Eurodistricts, co-operations on municipal level, etc.). In consequence, the vertical dimension of interaction and exchange between the different geographical levels of co-operations is to be taken into consideration. The situation is quite different in the lake Constance region, where interregional networks and relations exist, but co-operations with a smaller geographical perimeter are far less institutionalized.

- Structural patterns of interactions: While cross-border organizations in the Lake Constance region are strongly dominated by horizontal interrelations, respective relations in the Upper Rhine region also show important vertical elements. That means, in consequence, that around Lake Constance, an interregional moment is of importance, whereas in the Upper Rhine region, cross-border organizations emphasize a more vertical orientation by networking of the different levels involved and by a synchronization of different geographical perimeter/subspaces;

- Organizational structure and processes: The main organizations in the Upper Rhine regions can be seen as classical institution building and are characterised by a broad set of organizational bodies and boards. The degree of formalization is high. Responsibilities, processes as well as procedures are defined and regulated. With the Tri-National Metropolitan Region Upper Rhine also the interrelations and the roles between the different organizations in the cross-border governance system are structured. In contrast, the cross-border governance system in the Lake Constance Region is dominated by flexible, personal, and equal relationships. In consequence exchange and coordination between the different organizations are far less certain and depend on various factors like personal contacts or networks.

- Decision-making, conflict management and transaction costs: Due to the stronger institutionalization in the Upper Rhine region, the regional cross-border bodies show more competencies for binding strategic decisions. Nevertheless, the political commitment to make such decisions is not always given and, in consequence, you find currently the tendency to adopt indefinite resolutions instead of clear decisions. In the Lake Constance Region, the decision finding process sometimes requires extensive processes and negotiations. In addition, conflict-management is attested to be quite low in the region, consensus oriented sunshine-policies are dominating.

- Typology of involved actors: Both regions show a strong dominance of public actors, as it is often the case for cross-border co-operation in general. Actors of other sectors than the public one (private, societal) are integrated almost exclusively on the operative level (project level, working groups), not at the strategic/institutional level.

- Thematic scope: Both regions cover with their organizational setting the traditional policy fields of cross-border interest. That means that initiatives are to be found in the policy fields of planning, economic development, education and research, environment.

- Legal Status: Both regions show no legal status for organizations covering the whole cross-border perimeter. Moreover, in both regions, the main organizations are based on multilateral agreements between the partners. Instruments offering a legal status for cross-border co-operations like the European Grouping for Territorial Cooperation (EGTC) or the Local Cross-border Cooperation Grouping (LCCG) are only used for organizations in the subspaces.

6. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Markus Perkmann. “Cross-Border Regions in Europe—Significance and Drivers of Regional Cross-Border Co-Operation.” European Urban and Regional Studies 10 (2003): 153–71. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Joachim Beck, and Eddie Pradier. “Governance-Strukturen der Grenzregionen.” In Überregionale Partnerschaften in Grenzüberschreitenden Verflechtungsräumen. Bonn: Bundesamt für Bauwesen und Raumordnung, 2011. [Google Scholar]

- James Anderson, Liam O’Dowd, and Thomas M. Wilson. New Borders for a Changing Europe: Cross-Border Cooperation and Governance. London: Psychology Press, 2003. [Google Scholar]

- Carola Fricke. “Spatial Governance across Borders Revisited: Organizational Forms and Spatial Planning in Metropolitan Cross-border Regions.” European Planning Studies 23 (2015): 849–70. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sabine Dörry, and Olivier Walther. “Contested relational policy spaces in two European border regions.” Environment and Planning 47 (2015): 338–55. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Olivier Walther, and Bernard Reitel. “Cross-Border policy networks in the Basel region: The effect of national borders and brokerage roles.” Space & Polity 17 (2013): 217–36. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sabine Dörry, and Antoine Decoville. “Governance and transportation policy networks in the cross-border metropolitan regions of Luxembourg. A social network analysis.” European Urban and Regional Studies, 2013. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Antoine Decoville, Frédéric Durand, Christophe Sohn, and Olivier Walther. “Comparing Cross-Border Metropolitan Integration in Europe: Towards a Functional Typology.” Journal of Borderlands Studies 28 (2013): 221–37. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Christophe Sohn, Bernard Reitel, and Olivier Walther. “Cross-border metropolitan integration in Europe: the case of Luxembourg, Basel, and Geneva.” Environment and Planning C: Government and Policy 27 (2009): 922–39. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Enrico Gualini. “Cross-Border Governance: Inventing Regions in a Trans-National Multi-Level Polity.” DISP 152 (2003): 43–52. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jen Nelles, and Frédéric Durand. “Political rescaling and metropolitan governance in cross-border regions: Comparing the cross-border metropolitan areas of Lille and Luxembourg.” European Urban and Regional Studies 21 (2014): 104–22. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Iain Deas, and Alex Lord. “From a New Regionalism to an Unusual Regionalism? The Emergence of Non-Standard Regional Spaces and Lessons for the Territorial Reorganisation of the State.” Urban Studies 43 (2006): 1847–77. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jens-Dieter Gabbe, Viktor Von Malchus, and Association of European Border Regions. Zusammenarbeit europäischer Grenzregionen: Bilanz und Perspektiven. Baden-Baden: Nomos-Verlag-Gesellschaft, 2008. [Google Scholar]

- Oliver Pfirrmann, and Kristina Zumbusch. “Cross-border regions—Examples of supraregional cooperation processes in science policy.” In Paper presented at the PRIME Conference [Policies for Research and Innovation in the Move towards the European Research Area], “Unpacking Geographical Spaces in research and Innovation in Europe”, Bilbao, Spain, 4–6 October 2005; Available online: https://www.alexandria.unisg.ch/Publikationen/Zitation/Kristina_Zumbusch (accessed on 5 May 2015).

- Lefteris Topaloglou, Dimitris Kallioras, Panos Manetos, and George Petrakos. “A Border Regions Typology in the Enlarged European Union.” Journal of Borderlands Studies 20 (2005): 67–89. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kees Terlouw. “Border Surfers and Euroregions: Unplanned Cross-Border Behaviour and Planned Territorial Structures of Cross-Border Governance.” Planning Practice & Research 27 (2012): 351–66. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Joachim Blatter. “Debordering the World of States: Toward a Multi-Level System in Europe and a Multipolity system in North America—Insights from Border Regions.” European Journal of International Relations 7 (2001): 175–209. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Joachim Blatter. “From ‘Spaces of Place’ to ‘Spaces of Flows’? Territorial and Functional Governance in Cross-Border Regions in Europe and North America.” International Journal of Urban and Regional Research 28 (2004): 530–48. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kristina Zumbusch, and Roland Scherer. “Limits for successful cross-border governance of environmental and spatial development: The Lake Constance Region.” Procedia—Social and Behavioral Sciences 14 (2011): 101–20. [Google Scholar]

- Dietrich Fürst. “Regional Governance—Was ist neu an dem Ansatz und was bietet er? ” In Grenzüberschreitende Zusammenarbeit Leben und Erforschen (Band 2): Governance in Deutschen Grenzregionen. Edited by Joachim Beck and Birte Wassenberg. Stuttgart: Franz Steiner Verlag, 2011, pp. 89–106. [Google Scholar]

- Dietrich Fürst. “Regional Governance [RG]—was hat die deutsche Diskussion gebracht? ” In Regieren—Festschrift für Hubert Heinelt. Edited by Björn Egner, Michael Haus and Georgios Terizakis. Wiesbaden: VS Verlag für Sozialwissenschaften, 2012, pp. 361–77. [Google Scholar]

- Roland Scherer. “Zum Zusammenspiel grenzüberschreitender Netzwerke.” IMPacts 4 (2012): 26–28. [Google Scholar]

- Roland Scherer. Regionale Innovationskoalitionen: Bedeutung und Erfolgsfaktoren Von Regionalen Governance-Systemen. Bern: Haupt Verlag, 2006. [Google Scholar]

- Roland Scherer, and Kristina Zumbusch. “Multiple Rationalities in Regional Development.” In Multi-Rational Management: Mastering Conflicting Demands in a Pluralistic Environment. Edited by Johannes Rüegg-Stürm and Kuno Schedler. London: Palgrave Macmillan, 2014, pp. 100–21. [Google Scholar]

- James Rosenau, and Ernst-Otto Czempiel. Governance without Government: Order and Change in World Politics. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 1992. [Google Scholar]

- Roderick Arthur William Rhodes. “The New Governance: Governing Without Government.” Political Studies 44 (1996): 652–67. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Donald F. Kettl. The Transformation of Governance: Public Administration for the Twenty-First Century. Baltimore: JHU Press, 2015. [Google Scholar]

- Adrienne Héritier, and Martin Rhodes. New Modes of Governance in Europe: Governing in the Shadow of Hierarchy. London: Palgrave Macmillan, 2011. [Google Scholar]

- Olivier Kramsch, and Barbara Hooper. Cross-Border Governance in the European Union. London: Taylor and Francis, 2004. [Google Scholar]

- Liesbet Hooghe, and Gary Marks. “Unraveling the central state, but how? Types of multi-level governance.” American Political Science Review 97 (2003): 233–45. [Google Scholar]

- Heinz Müller-Schnegg. Grenzüberschreitende Zusammenarbeit in der Bodenseeregion. Bamberg: Rosch, 1994. [Google Scholar]

- Roland Scherer, and Klaus-Dieter Schnell. “Die Stärke schwacher Netze. Entwicklung und aktuelle Situation der grenzübergreifenden Zusammenarbeit in der Regio Bodensee.” In Jahrbuch des Föderalismus. Baden-Baden: Nomos, 2002, pp. 502–18. [Google Scholar]

- Markus Perkmann. “Policy entrepreneurship and multilevel governance: A comparative study of European cross-border regions.” Environment and Planning C: Government and Policy 25 (2007): 861–79. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dietrich Fürst. “Regional Governance.” In Governance—Regieren in komplexen Regelsystemen. Eine Einführung. Edited by Arthur Benz and Nicolai Dose. Wiesbaden: VS Verlag für Sozialwissenschaften, 2010, pp. 49–68. [Google Scholar]

© 2015 by the authors; licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Zumbusch, K.; Scherer, R. Cross-Border Governance: Balancing Formalized and Less Formalized Co-Operations. Soc. Sci. 2015, 4, 499-519. https://doi.org/10.3390/socsci4030499

Zumbusch K, Scherer R. Cross-Border Governance: Balancing Formalized and Less Formalized Co-Operations. Social Sciences. 2015; 4(3):499-519. https://doi.org/10.3390/socsci4030499

Chicago/Turabian StyleZumbusch, Kristina, and Roland Scherer. 2015. "Cross-Border Governance: Balancing Formalized and Less Formalized Co-Operations" Social Sciences 4, no. 3: 499-519. https://doi.org/10.3390/socsci4030499