Developing an Explanatory Risk Management Model to Comprehend the Employees’ Intention to Leave Public Sector Organization

Abstract

:1. Introduction

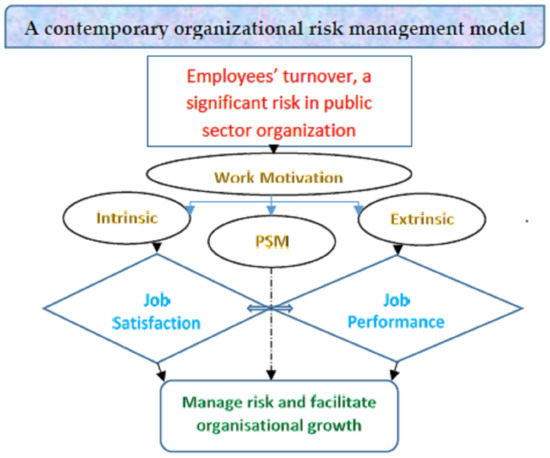

2. An Explanatory Risk Management Model

3. Examining Relationship between Work Motivations and Job Performance and Job Satisfaction

3.1. Relationship between Work Motivations and Job Performance

- (1)

- A higher level of PSM of an individual is favourable to join a public sector organization;

- (2)

- PSM is positively correlated with job performance; and

- (3)

- Individual employees’ performance can be easily managed if the public sector organizations appoint workforce having a higher level of PSM.

3.2. Relationship between Work Motivation and Job Satisfaction

3.3. Relationship between Job Satisfaction and Job Performance

4. Determinants of the Intention to Leave an Organization

4.1. The Public Sector Context

4.2. Turnover Intention in the Public Sector

5. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Allen, David, and Rodger Griffeth. 1999. Job Performance and Turnover: A Review and Integrative Multi-Route Model. Human Resource Management Review 9: 525–48. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Alonso, Pablo, and Gregory Lewis. 2001. Public Service Motivation and Job Performance: Evidence from the Federal Sector. The American Review of Public Administration 31: 363–80. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Anderfuhren-Biget, Simon Varone, Frederic Giauque David, and Adrian Ritz. 2010. Motivating Employees of the Public Sector: Does Public Service Motivation Matter? International Public Management Journal 13: 213–46. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bellé, Nicola. 2013. Experimental Evidence on the Relationship between Public Service Motivation and Job Performance. Public Administration Review 73: 143–53. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bertelli, Anthony. 2007. Determinants of Bureaucratic Turnover Intention: Evidence from the Department of the Treasury. Journal of Public Administration Research and Theory 17: 235–58. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bertelli, Anthony, and David Lewis. 2013. Policy Influence, Agency-Specific Expertise, and Exit in the Federal Service. Journal of Public Administration Research and Theory 23: 223–45. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bluedorn, Allen. 1982a. A unified model of turnover from organizations. Human Relations 35: 135–53. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bluedorn, Allen. 1982b. Managing turnover strategically. Business Horizons 25: 6–12. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bonner, Sarah, and Geoffrey Sprinkle. 2002. The effects of monetary incentives on effort and task performance: Theories, evidence, and a framework for research. Accounting, Organizations and Society 27: 303–45. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Borgogni, Laura, Dello Russo Salvia, Laura Petitta, and Michele Vecchione. 2010. Predicting job satisfaction and job performance in a privatized organization. International Public Management Journal 13: 275–96. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Boswell, Wendy, John Boudreau, and Jan Tichy. 2005. The relationship between employee job change and job satisfaction: The honeymoon-hangover effect. Journal of Applied Psychology 90: 882–92. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Boyne, George, Oliver James, Peter John, and Nicolai Petrovsky. 2010. Does Public Service Performance Affect Top Management Turnover? Journal of Public Administration Research and Theory 20: i261–i279. [Google Scholar]

- Brayfield, Arthur, and Walter Crockett. 1955. Employee attitudes and employee performance. Psychological Bulletin 52: 396–424. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bright, Leonard. 2007. Does Person-Organization Fit Mediate the Relationship Between Public Service Motivation and the Job Performance of Public Employees? Review of Public Personnel Administration 27: 361–79. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bright, Leonard. 2008. Does public service motivation really make a difference on the job satisfaction and turnover intentions of public employees? The American Review of Public Administration 38: 149–66. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bright, Leonard. 2013. Where Does Public Service Motivation Count the Most in Government Work Environments? A Preliminary Empirical Investigation and Hypotheses. Public Personnel Management 42: 5–26. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Carmeli, Abraham, and Jacob Weisberg. 2006. Exploring turnover intentions among three professional groups of employees. Human Resource Development International 9: 191–206. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, Gilad, Robert Ployhart, Helena Cooper Thomas, Neil Anderson, and Paul Bliese. 2011. The power of momentum: A new model of dynamic relationships between job satisfaction change and turnover intentions. Academy of Management Journal 54: 159–81. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chiu, Randy, and Anne Marie Francesco. 2003. Dispositional traits and turnover intention. Examining the mediating role of job satisfaction and affective commitment. International Journal of Manpower 24: 284–98. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cho, Yoon Jik, and James Perry. 2012. Intrinsic motivation and employee attitudes: Role of managerial trustworthiness, goal directedness, and extrinsic reward expectancy. Review of Public Personnel Administration 32: 382–406. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Condly, Steven, Richard Clark, and Harold Stolovitch. 2003. The Effects of Incentives on Workplace Performance: A Meta-analytic Review of Research Studies. Performance Improvement Quarterly 16: 46–63. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cowley, Edd, and Sarah Smith. 2014. Motivation and mission in the public sector: Evidence from the World Values Survey. Theory and Decision 76: 241–63. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- de Moura, Georgina Randsley, Dominic Abrams, Carina Retter, Sigridur Gunnarsdottir, and Kaori Ando. 2009. Identification as an organizational anchor: How identification and job satisfaction combine to predict turnover intention. European Journal of Social Psychology 39: 540–57. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Deci, Edward, Richard Ryan, and Richard Koestner. 1999. A meta-analytic review of experiments examining the effects of extrinsic rewards on intrinsic motivation. Psychological Bulletin 125: 627–68. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Delobelle, Peter, Jakes Rawlinson, Sam Ntuli, Inah Malatsi, Rika Decock, and Anne Marie Depoorter. 2011. Job satisfaction and turnover intent of primary healthcare nurses in rural south africa: A questionnaire survey. Journal of Advanced Nursing 67: 371–83. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- DeSantis, Victor, and Samantha Durst. 1996. Comparing job satisfaction among public- and private-sector employees. The American Review of Public Administration 26: 327–43. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dysvik, Anders, and Bard Kuvaas. 2010. Intrinsic motivation as a moderator on the relationship between perceived job autonomy and work performance. European Journal of Work and Organizational Psychology 20: 367–87. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Dysvik, Anders, and Bard Kuvaas. 2013. Intrinsic and extrinsic motivation as predictors of work effort: The moderating role of achievement goals. British Journal of Social Psychology 52: 412–30. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Ellett, Alberta, Jacquelyn Ellis, Tonya Westbrook, and Denise Dews. 2007. A qualitative study of 369 child welfare professionals’ perspectives about factors contributing to employee retention and turnover. Children and Youth Services Review 29: 264–81. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Furnham, Adrian, Andreas Eracleous, and Tomas Chamorro-Premuzic. 2009. Personality, motivation and job satisfaction: Hertzberg meets the Big Five. Journal of Managerial Psychology 24: 765–79. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Garbers, Yvonne, and Udo Konradt. 2014. The effect of financial incentives on performance: A quantitative review of individual and team-based financial incentives. Journal of Occupational and Organizational Psychology 87: 102–37. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Georgellis, Yannis, Elisabetta Iossa, and Vurain Tabvuma. 2011. Crowding Out Intrinsic Motivation in the Public Sector. Journal of Public Administration Research and Theory 21: 473–93. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Grant, Adam. 2008. Does Intrinsic Motivation Fuel the Prosocial Fire? Motivational Synergy in Predicting Persistence, Performance, and Productivity. Journal of Applied Psychology 93: 48–58. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Green Version]

- Griffeth, Rodger, Peter Hom, and Stefan Gaertner. 2000. A meta-analysis of antecedents and correlates of employee turnover: Update, moderator tests, and research implications for the next millennium. Journal of Management 26: 463–88. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Grissom, Jason, Jill Nicholson-Crotty, and Lael Keiser. 2012. Does my boss’s gender matter? Explaining job satisfaction and employee turnover in the public sector. Journal of Public Administration Research and Theory 22: 649–73. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hackman, Richard, and Greg Oldham. 1976. Motivation through the design of work: Test of a theory. Organizational Behavior and Human Performance 16: 250–79. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hellman, Chan. 1997. Job satisfaction and intent to leave. The Journal of Social Psychology 137: 677–89. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Herzberg, Frederick. 1968. One more time: How do you motivate employees? Harvard Business Review 81: 87–96. [Google Scholar]

- Herzberg, Frederick. 1974. Motivation-hygiene profiles: Pinpointing what ails the organization. Organizational Dynamics 3: 18–29. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Herzberg, Frederick, Bernard Mausner, and Barbara Bloch Snyderman. 1962. The Motivation to Work, 2nd ed. New York: Wiley. [Google Scholar]

- Hom, Peter, and Angelo Kinicki. 2001. Toward a greater understanding of how dissatisfaction drives employee turnover. Academy of Management Journal 44: 975–87. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Huang, Xu, and Evert Van De Vliert. 2003. Where intrinsic job satisfaction fails to work: National moderators of intrinsic motivation. Journal of Organizational Behavior 24: 159–79. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hwang, Jee-In, and Hyejung Chang. 2008. Explaining turnover intention in Korean public community hospitals: Occupational differences. The International Journal of Health Planning and Management 23: 119–38. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Iaffaldano, Michelle, and Paul Muchinsky. 1985. Job Satisfaction and Job Performance. A Meta-Analysis. Psychological Bulletin 97: 251–73. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Islam, Jesmin, Quazi Ali, and Azizur Rahman. 2011. Nexus between cultural dissonance, management accounting systems, and managerial effectiveness: Evidence from an asian developing country. Journal of Asia-Pacific Business 12: 280–303. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Joo, Baek-kyoo, Chang-Wook Jeung, and Hea Jun Yoon. 2010. Investigating the influences of core self-evaluations, job autonomy, and intrinsic motivation on in-role job performance. Human Resource Development Quarterly 21: 353–71. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Judge, Timothy, Carl Thoresen, Joyce Bono, and Gregory Patton. 2001. The job satisfaction-job performance relationship: A qualitative and quantitative review. Psychological Bulletin 127: 376–407. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Jung, Chan Su. 2014. Why Are Goals Important in the Public Sector? Exploring the Benefits of Goal Clarity for Reducing Turnover Intention. Journal of Public Administration Research and Theory 24: 209–34. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lambert, Eric, and Nancy Hogan. 2009. The Importance of Job Satisfaction and Organizational Commitment in Shaping Turnover Intent: A Test of a Causal Model. Criminal Justice Review 34: 96–118. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lawler, Edward, and Lyman William Porter. 1967. The effect of performance on job satisfaction. Industrial Relations: A Journal of Economy and Society 7: 20–28. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lee, Geon, and Benedict Jimenez. 2011. Does Performance Management Affect Job Turnover Intention in the Federal Government? The American Review of Public Administration 41: 168–84. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, Bangcheng, Jianxin Liu, and Jin Hu. 2010. Person-organization fit, job satisfaction, and turnover intention: An empirical study in the chinese public sector. Social Behavior and Personality: An International Journal 38: 615–25. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Locke, Edwin. 1970. Job satisfaction and job performance: A theoretical analysis. Organizational Behavior and Human Performance 5: 484–500. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Locke, Edwin. 1991. The motivation sequence, the motivation hub, and the motivation core. Organizational Behavior and Human Decision Processes 50: 288–99. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Locke, Edwin, and Gray Latham. 1990. Work motivation and satisfaction: Light at the end of the tunnel. Psychological Science 4: 240–46. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Luna-Arocas, Roberto, and Joaquin Camps. 2008. A model of high performance work practices and turnover intentions. Personnel Review 37: 26–46. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Maertz, Carl, and Rodger Griffeth. 2004. Eight Motivational Forces and Voluntary Turnover: A Theoretical Synthesis with Implications for Research. Journal of Management 30: 667–83. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Maidani, Ebrahim. 1991. Comparative study of Herzberg’s two-factor theory of job satisfaction among public and private. Public Personnel Management 20: 441. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Markovits, Yannis, Ann Davis, Doris Fay, and Rolf van Dick. 2010. The link between job satisfaction and organizational commitment: Differences between public and private sector employees. International Public Management Journal 13: 177–96. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Meier, Kenneth, and Alisa Hicklin. 2008. Employee Turnover and Organizational Performance: Testing a Hypothesis from Classical Public Administration. Journal of Public Administration Research and Theory 18: 573–90. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Mihajlov, Snezana, and Nenad Mihajlov. 2016. Comparing public and private employees’ job satisfication and turnover intention. MEST Journal 4: 75–86. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mobley, William. 1977. Intermediate linkages in the relationship between job satisfaction and employee turnover. Journal of Applied Psychology 62: 237–40. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Moynihan, Donald, and Noel Landuyt. 2008. Explaining Turnover Intention in State Government: Examining the Roles of Gender, Life Cycle, and Loyalty. Review of Public Personnel Administration 28: 120–43. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Moynihan, Donald, and Sanjay Pandey. 2008. The Ties that Bind: Social Networks, Person-Organization Value Fit, and Turnover Intention. Journal of Public Administration Research and Theory 18: 205–27. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Naff, Katherine, and John Crum. 1999. Working for America: Does public service motivation make a difference? Review of Public Personnel Administration 19: 5–16. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nyberg, Aanthony. 2010. Retaining your high performers: Moderators of the performance—job satisfaction—voluntary turnover relationship. Journal of Applied Psychology 95: 440–53. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Park, Chunoh, Nicholas Lovrich, and Dennis Soden. 1988. Testing Herzberg’s Motivation Theory in a Comparative Study of U.S. and Korean Public Employees. Review of Public Personnel Administration 8: 40–60. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pedersen, Mogens Jin. 2013. Public Service Motivation and Attraction to Public Versus Private Sector Employment: Academic Field of Study as Moderator? International Public Management Journal 16: 357–85. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Perry, James. 1997. Antecedents of Public Service Motivation. Journal of Public Administration Research and Theory 7: 181–97. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Perry, James, and Annie Hondeghem. 2008. Building theory and empirical evidence about public service motivation. International Public Management Journal 11: 3–12. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Perry, James, and Lois Recascino Wise. 1990. The motivational bases of public service. Public Administration Review 50: 367–73. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Peterson, Shari. 2004. Toward a Theoretical Model of Employee Turnover: A Human Resource Development Perspective. Human Resource Development Review 3: 209–27. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pitts, David, Marvel John, and Sergio Fernandez. 2011. So Hard to Say Goodbye? Turnover Intention among U.S. Federal Employees. Public Administration Review 71: 751–60. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Podsakoff, Nathan, Jeffery LePine, and Marcie LePine. 2007. Differential challenge stressor-hindrance stressor relationships with job attitudes, turnover intentions, turnover, and withdrawal behavior: A meta-analysis. Journal of Applied Psychology 92: 438–54. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Porter, Lyman William, Richard M. Steers, Richard T. Mowday, and Paul V. Boulian. 1974. Organizational Commitment, Job-Satisfaction, and Turnover among Psychiatric Technicians. Journal of Applied Psychology 59: 603–9. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Price, James. 1989. The impact of turnover on the organization. Work and Occupations 16: 461–73. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Prihandinisari, Carolina, Azizur Rahman, and John Hicks. 2016. What Motivate Individuals to Join Public Service? Examining Public Service Motivation in a Non-Western Cultural Context. In 5th Global Business and Finance Research Conference. Berwick: World Business Institute, pp. 1–13. [Google Scholar]

- Rahman, Azizur, and Najmul Hasan. 2017. Modeling Effects of KM and HRM Processes to the Organizational Performance and Employee’s Job Satisfaction. International Journal of Business and Management 12: 35–45. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Rosenfeld, Michael, and Steve Zdep. 1971. Instrinsic-extrinsic aspects of work and their demographic correlates. Psychological Reports 28: 359–62. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rutherford, Brian, Yujie Wei, JungKun Park, and Won-Moo Hur. 2012. Increasing job performance and reducing turnover: An examination of female Chinese salespeople. Journal of Marketing Theory and Practice 20: 423–36. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ryan, Richard, and Edward Deci. 2000. Intrinsic and extrinsic motivations: Classic definitions and new directions. Contemporary Educational Psychology 25: 54–67. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sachau, Daniel. 2007. Resurrecting the motivation-hygiene theory: Herzberg and the positive psychology movement. Human Resource Development Review 6: 377–93. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schleicher, Deidra, John Watt, and Gary Greguras. 2004. Reexamining the job satisfaction-performance relationship: The complexity of attitudes. Journal of Applied Psychology 89: 165–77. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sell, Lea, and Bryan Cleal. 2011. Job Satisfaction, Work Environment, and Rewards: Motivational Theory Revisited. LABOUR 25: 1–23. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Smith, Deborah, and Joel Shields. 2013. Factors Related to Social Service Workers’ Job Satisfaction: Revisiting Herzberg’s Motivation to Work. Administration in Social Work 37: 189–98. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sousa-Poza, Alfonso, and Andres Sousa-Poza. 2007. The effect of job satisfaction on labor turnover by gender: An analysis for Switzerland. The Journal of Socio-Economics 36: 895–913. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Spector, Paul, Tammy Allen, Steven Poelmans, Laurent Lapierre, Cary Cooper, Michael O’Driscoll, Juan Sanchez, Nureya Abarca, Matilda Alexandrova, Barbara Beham, and et al. 2007. Cross-national differences in relationships of work demands, job satisfaction, and turnover intentions with work–family conflict. Personnel Psychology 60: 805–35. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Steel, Robert. 2002. Turnover theory at the empirical interface: Problems of fit and function. Academy of Management Review 27: 346–60. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Steel, Robert, and John Lounsbury. 2009. Turnover process models: Review and synthesis of a conceptual literature. Human Resource Management Review 19: 271–82. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Steers, Richard, Richard Mowday, and Debra Shapiro. 2004. The future of work motivation theory. Academy of Management Review 29: 379–87. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Swailes, Stephen, and Saleh Al Fahdi. 2011. Voluntary turnover in the Omani public sector: An Islamic values perspective. International Journal of Public Administration 34: 682–92. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Taylor, Jeannette. 2007. The impact of public service motives on work outcomes in Australia: A comparative multi-dimensional analysis. Public Administration 85: 931–59. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Taylor, Jeannette. 2014. Public service motivation, relational job design, and job satisfaction in local government. Public Administration 92: 902–18. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Taylor, Jeannette, and Ranald Taylor. 2011. Working hard for more money or working hard to make a difference? Efficiency wages, public service motivation, and effort. Review of Public Personnel Administration 31: 67–86. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Taylor, Jeannette, and Janathan Westover. 2011. Job satisfaction in the public service. Public Management Review 13: 731–51. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tett, Robert, and John Meyer. 1993. Job satisfaction, organizational commitment, turnover intention, and turnover: Path analyses based on meta-analytic findings. Personnel Psychology 46: 259–93. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Van Iddekinge, Chad, Philip Roth, Dan Putka, and Stephen Lanivich. 2011. Are you interested? A meta-analysis of relations between vocational interests and employee performance and turnover. Journal of Applied Psychology 96: 1167–94. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Vandenabeele, Wouter. 2007. Toward a public administration theory of public service motivation. Public Management Review 9: 545–56. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vandenabeele, Wouter. 2008. Development of a public service motivation measurement scale: Corroborating and extending perry’s measurement instrument. International Public Management Journal 11: 143–67. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vandenabeele, Wouter. 2009. The mediating effect of job satisfaction and organizational commitment on self-reported performance: More robust evidence of the PSM—Performance relationship. International Review of Administrative Sciences 75: 11–34. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vandenabeele, Wouter. 2011. Who Wants to Deliver Public Service? Do Institutional Antecedents of Public Service Motivation Provide an Answer? Review of Public Personnel Administration 31: 87–107. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, Yau-De, Chyan Yang, and Kuei-Ying Wang. 2012. Comparing Public and Private Employees’ Job Satisfaction and Turnover. Public Personnel Management 41: 557–73. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Warr, Peter, John Cook, and Toby Wall. 1979. Scales for the measurement of some work attitudes and aspects of psychological well-being. Journal of Occupational Psychology 52: 129–48. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Westover, Jonathan, and Jeannette Taylor. 2010. International differences in job satisfaction. International Journal of Productivity and Performance Management 59: 811–28. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wiersma, Uco Jillert. 1992. The effects of extrinsic rewards in intrinsic motivation: A meta-analysis. Journal of Occupational and Organizational Psychology 65: 101–14. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zimmerman, Ryan, and Todd Darnold. 2009. The impact of job performance on employee turnover intentions and the voluntary turnover process. A meta-analysis and path model. Personnel Review 38: 142–58. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Author(s) | Objectives | Method | Major Findings |

|---|---|---|---|

| Maidani (1991) | Compare public and private sector job satisfaction using Herzberg’s Two-Factor Theory | It used a survey of 173 and 177 respondents from private and public sector data, with staffs’ work factor importance and job satisfaction measurement (Resenfeld and Zdep 1971; Warr et al. 1979). | Motivators and hygiene factors were sources of satisfaction for both sectors. Employee in public sector had a higher level of job satisfaction than private sector. Moreover, public sector employees recognized higher value on the hygiene factors. |

| DeSantis and Durst (1996) | Test differences in job satisfaction between public and private sector. | The study utilized a panel data from the National Longitudinal Surveys of Youth (NLSY) in the US. The survey collected 12,686 respondents’ data yearly from 1979–1985. | In general, both public and private sector showed similar perception in JS. Regarding salary, private staffs recognized it as key factor, and young employees considered the actual level of income is important. |

| Carmeli and Weisberg (2006) | Assess the effects of key factors on turnover intention on public sector (social workers and financial officers) and private sector (lawyers). | A study in Israel with the data from social workers (228) and financial officers (98), and professional lawyers (183). A structured questionnaire survey was conducted to collect the data, and it employed two hierarchical regressions analyses. | Affective commitment and intrinsic job satisfaction (IJS) were negatively linked to turnover, but no link between IJS and turnover. IJS had more impact on turnover than extrinsic job satisfaction (EJS). No link between job performance and turnover. Private sector had lower turnover than public sector. |

| Markovits et al. (2010) | Examine the effects of organizational commitment and JS on public and private sectors. | A sample of 257 private and 360 public sector staffs data by the MSQ (Warr et al. 1979) and a scale by Tett and Meyer (1993) were employed. | Extrinsic and intrinsic satisfactions were more strongly related to affective and normative commitment for public sector employees than for private sector. |

| Wang et al. (2012) | Compare job satisfaction and turnover intentions of public and private sector in Taiwan. | The study involved 243 public employees and 240 private employees (overall return rate of 48.3%) in Taiwan. The Chinese version of the MSQ was used as measurement. | Public employees had higher IJS, but lower EJS and turnover intent than private sector. The negative relationship between EJS and turnover intention is weaker in public than in private employees. |

| Cowley and Smith (2014) | Compare intrinsic motivation of public and private sector. | The study used data from the World Values Survey and used 51 countries. | A higher level of corruption in a country had negative effect on the proportion of intrinsically motivated public sector staffs. |

| Mihajlov and Mihajlov (2016) | Compare job satisfaction and turnover intentions of private and public sector in Serbia | The study used questionnaires based survey data from a random sample of 234 people of which 166 and 68 employees were from public and private sectors respectively. | Staff in public sector showed much higher level of JS and much lower level of turnover against private sector. Also public employees have a higher level of EJS but a lower level of IJS than their counterparts in private sector. |

| Author(s) | Objectives | Method | Major Findings |

|---|---|---|---|

| Bertelli (2007) | Examine the determinants of turnover intention in government service. | The study used the 2002 Federal Human Capital Survey (FHCS, USA). The targeted organizations were the Internal Revenue Service (IRS) and the Office of the Comptroller of the Currency (OCC) both are under the U.S. Treasury. | It found that job involvement and intrinsic motivations vs friendship solidarity with co-workers and supervisors both decrease the likelihood of turnover. Subordinates’ turnover were not influenced by perceived rewards. |

| Bertelli and Lewis (2013) | Analyze turnover intention among federal executives, USA. Their model also considered agency-specific human capital and out-side options (labor market). | It used data from the 2007–2008 Survey on the Future of Government Service, a survey conducted by the Princeton Survey Research Center. The overall response rate for the survey is 34% (2398/7151) with 2069 completed the full survey. | The perceived availability of outside options increases probability of executive turnover. The influence of outside options on turnover is conditional on the presence of agency-specific human capital. |

| Boyne et al. (2010) | Explore whether public service performance makes a difference to the turnover of top managers in public organizations. | The study used 4 years (2002–2006) of panel data on all 148 English principal local governments (London boroughs, metropolitan boroughs, unitary authorities, and county councils). | Managers were more likely to leave for poor performance. The negative link between performance and turnover was weaker for chief executives than senior managements. |

| Grissom et al. (2012) | Assess the impact of manager gender on the job satisfaction and turnover of public sector workers. | The data on public school teachers used in this study were obtained from the National Center for Education Statistics (NCES) in the US. | Teachers preferred male principals. Gender incongruent more likely influenced job satisfaction and turnover intention for men, than women. |

| Moynihan and Landuyt (2008) | Test a turnover model focusing on life cycle stability, gender, organizational loyalty, diversity policy. | A total of 62,628 staff was surveyed in 53 different state agencies in Texas, US, resulting in 34,668 usable responses, a response rate of more than 55%. | Employees reached life cycle stability, were less likely to quit. Females were less likely to quit public sector. From HRM view, IJS and salary had big effects on turnover. |

| Moynihan and Pandey (2008) | Examine the role of social networks on turnover intention, and to examine how employee values shaped turnover intention. | Data used in this study were collected from 12 organizations in the northeastern part of the US in 2005; include private nonprofit (5) and public service organization (7). Of the 531 comprising the sample, 326 responded for a response rate of 61.4%. | Staff turnover affected by internal network. Staff who had a sense of obligation toward co-workers were less likely to leave in the short and long term. JS and years in position were key turnover factors. P-O fit negatively affected long-term turnover. |

| Jung (2014) | Explore the influence of goal clarity on turnover intentions in public organizations. | The main data sources for this analysis were the 2005 MPS and the 2005 PART, the samples comprised 18,242 US federal employees. | Goal specificity and goal importance, pay, promotion, and training showed negative links to turnover. Internal alliance had negative effect on turnover, at both personal and organizational level. |

| Lee and Jimenez (2011) | Examine the influence of performance management on turnover intention in federal employees. | The study used data from the 2005 Merit Principles Survey conducted by the Merit Systems Protection Board (MSPB). The total number of federal employees who completed the survey was 36,926 or a response rate of 49.9%. | Performance-based reward system and supporting supervision were significantly and negatively related to JS and turnover. Job position had positive link with turnover, and a U-shape relation found between age and turnover. |

| Meier and Hicklin (2008) | Study the relations between staff turnover and organizational performance in public sector. | It used a database of the 1000+ Texas school districts for the academic years 1994 through 2002. The data set was a panel data set that includes nine years data on each school district. | In higher task difficulties, an inverted U-shaped link existed between turnover and performance. At some point higher level turnover had detrimental effects on performance. |

| Bright (2008) | Investigate the relationship among PSM, job satisfaction, and the turnover intentions mediated by P-O fit. | The sample of 205 employees from three public organizations in states of Oregon, Indiana, and Kentucky was analysed. | PSM showed a big and positive link to P-O fit, but P-O fit had a negative link to turnover. If P-O fit was taken into account, PSM showed relation to JS and turnover. |

| Liu et al. (2010) | Investigate the relationship among P-O fit, job satisfaction, and turnover intentions in China public sector. | The study used a survey data from 259 part-time Master in Public Administration (MPA) program student but also full-time public sector employees. | P-O fit had noticeable positive link to JS, and negative link to turnover. Age and tenure had a strongly negative effect on turnover. JS mediates P-O fit and turnover intentions. |

| Pitts et al. (2011) | Explore key factors (e.g., demographic, organizational and satisfaction, workplace) that affected turnover. | The 2006 Federal Human Capital Survey (FHCS) data was used which consists a sample of more than 200,000 US federal government employees. | The most significant factors that affect turnover intentions of federal employees were job satisfaction, satisfaction with progress, and age. |

© 2020 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Prihandinisari, C.; Rahman, A.; Hicks, J. Developing an Explanatory Risk Management Model to Comprehend the Employees’ Intention to Leave Public Sector Organization. J. Risk Financial Manag. 2020, 13, 200. https://doi.org/10.3390/jrfm13090200

Prihandinisari C, Rahman A, Hicks J. Developing an Explanatory Risk Management Model to Comprehend the Employees’ Intention to Leave Public Sector Organization. Journal of Risk and Financial Management. 2020; 13(9):200. https://doi.org/10.3390/jrfm13090200

Chicago/Turabian StylePrihandinisari, Carolina, Azizur Rahman, and John Hicks. 2020. "Developing an Explanatory Risk Management Model to Comprehend the Employees’ Intention to Leave Public Sector Organization" Journal of Risk and Financial Management 13, no. 9: 200. https://doi.org/10.3390/jrfm13090200