Pain Management at the End of Life in the Emergency Department: A Narrative Review of the Literature and a Practical Clinical Approach

Abstract

:1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Eligibility Requirements

2.2. Source of Information and Search Strategy

2.3. Extraction of Data

2.4. Summary of the Findings

2.5. Definitions Used

3. Results

3.1. Result of the Database Search

3.2. General Characteristics of the Included Studies

3.2.1. Pain Assessment

3.2.2. Drugs Prescription

3.2.3. Included Studies’ Results

| Author, Year of Publication | Type of Study | Aim of the Study | Population | Pain Assessment Tool Recommended | Drug(s) Evaluated | Results | Author’s Conclusions |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Bell, 2018 [29] | Review | Review the care of geriatric patients at the end of life | Elderly patients presenting in ED | Verbal pain assessments; For non-verbal patients, facial expressions and other nonverbal cues (moaning or withdrawal) should be observed | For mild/moderate pain: Acetaminophen (1000 mg orally or rectally 3 times per day for a total of 3 g/d) For severe pain: Morphine (2 to 5 mg, IV) (or equivalent analgesic (e.g., 0.3–0.8 mg hydromorphone IV)) and dose every 15 min titrated to pain relief. In the older population, it is the recommended practice to start with the lower dose but escalate quickly (every 15 min) as needed | N/A | Although the ED may not traditionally be designed to meet palliative care, ED providers have a great opportunity to identify patients with palliative care needs and initiate a goal-oriented palliative approach that can have an impact on patient care dramatically |

| Chan, 2021 [30] | Retrospective cohort analysis | To study the performance of EDs in identifying patients of imminent death and the use of opioid and anticholinergic as part of symptom relief agents for patients under EOL | Adult EOL patients admitted to the ED | NR | In EOL service group, 483/688 (70.20%) received opioid and 204/688 (29.65%) received anticholinergic. In non-EOL service group, 49/95 (51.58%) received opioid and 2/95 (2.11%) received anticholinergic | The ED-based EOL care had significantly more patients receiving symptomatic treatment | Emergency physicians are capable of recognising dying patients. Emergency department-based EOL service offers adequate palliation of symptoms |

| Coyne, 2021 [31] | Multicentre, prospective observational study | To describe the reported pain among cancer patients presenting to the ED, how pain is managed, and how pain may be associated with clinical outcomes | Adults with active cancer presenting to the ED | Numeric Rating Scale | No drugs restriction | NSAID, nonselective in 4.8%, NSAID, selective in 0.9%, Acetaminophen in 15.3%, Tramadol in 1.2%, short-acting opioid/narcotic in 31.4%, long-acting opioid/narcotic in 7.1%, other in 1.7% | Patients who present to the ED with severe pain may have a higher risk of mortality, especially those with poor functional status. Patients who require opioid analgesics in the ED are more likely to require hospital admission and are more at risk for 30-day hospital readmission. Need of protocol-driven targeted to at-risk groups |

| De Oliveira, 2021 [32] | Retrospective | To identify the prevalence of PC needs in patients who die at the ED and to assess the symptom control and the aggressiveness of the care received | Adults deceased at the ED | Numeric Rating Scale | Opioids 54/117 (81.8%) patients Paracetamol 25/117 (37.9%) patients NSAISs 4/117 (6.1%) patients | 384 adults died at the ED (median age 82 (IQR 72–89) years). 78.4% (95% CI 73.9% to 82.2%) presented PC needs. 3.0% (n = 9) were referred to the hospital PC team. 64.5% presented dyspnoea, 38.9% pain, 57.5% confusion. Dyspnoea was commonly medicated in 92%, pain in 56%, confusion in 8% | The study warns about an alarming situation of high PC needs at the ED but shows that ED clinicians likely prioritise curative-intended over palliative-intended interventions |

| Lamba, 2010 [33] | Review | To review the common emergency presentations in patients under hospice care | Patients in or worthy of hospice care, no age specification | NR | For patients with constant moderate to severe pain, use morphine in sustained release and immediate release forms. General principles for patients on opiate therapy: (1) calculate the morphine equivalent as a daily 24 h dose; (2) determine the breakthrough dose, which is usually 10% to 15% of this calculated daily dose; (3) titrate doses upward if pain is not controlled or more than 3 breakthrough doses are being used daily; and (4) reduce the calculated conversion dose of a new opioid by 25% to 50% when converting between different opioids because tolerance to one opioid does not imply equivalent tolerance to another because of variable opioid receptor affinity | N/A | Emergency clinicians often care for patients with a terminal illness. An understanding of hospice as a care system may increase the overall emergency clinician comfort level in discussing hospice as a care option, when appropriate, with patients and families. Using the multidisciplinary approach that is central to the hospice model may also facilitate effective management of patients under hospice care who present to the ED |

| Long, 2020 [34] | Review | The review provides a summary of palliative care in the ED, with a focus on the literature behind the management of EOL dyspnoea and cancer-related pain | Oncologic patients in palliative care, no age specification | Numerical rating scale, Wong–Baker FACES scale, the verbal rating scale or PAINAD | Nociceptive pain: Opioid first line for severe pain Acetaminophen or NSAIDs first line for mild to moderate pain Consider adjuvant pain medications as needed (e.g., ketamine) Neuropathic pain: Antidepressants or anticonvulsants Bone pain: NSAIDs first line for mild to moderate bone pain Severe pain will likely require opioids Add adjuvant pain medications as needed Other drugs suggested: ketamine, corticosteroids, antidepressants, anticonvulsants. In opioid-tolerant patients: administer 10 to 15% of total daily opioids dose. Reduce the dose of 25–50% in case of opioid switching or use the rapid fentanyl protocol (dose equal to 10% of total previous 24 h morphine equivalent or 50 mcg, repeat every 5 min apart and increase of 50–100% for the third administration if pain is not controlled) | N/A | The most effective therapy for cancer-related pain is opioids. For rapid alleviation of severe pain, emergency physicians may use a fentanyl rapid dose titration model. There is no literature supporting the notion that opioids hasten death at EOL |

| Rojas, 2016 [35] | Observational study | To develop a best practice initiative to assist actively dying patients in the ED | Actively elderly dying patients | NR | Consider a morphine IV drip, 5 mL/h, or a morphine IV bolus, 5 to 10 mg. Titrate drip every 15 min by 50% dose for comfort | 401 patients evaluated by palliative care team in the emergency department. 91/401 enrolled in hospice while in the emergency department. 36/401 were enrolled in the palliative care protocol. The success of the program has been measured through letters of appreciation received from patients’ families | Care of the dying patient includes an organised interdisciplinary approach to patient care that includes open communication, medication management, and environ- mental modifications |

| Siegel, 2017 [36] | Review | To increase the emergency physician’s knowledge of and comfort with symptom control in palliative and hospice patients | Hospice patients, no age specification | NR | WHO analgesic ladder for nociceptive pain: mild pain (step 1) non-opioids ± adjuvants; moderate pain (step 2) weak opioids ± non-opioid ± adjuvants; severe pain (step 3) strong opioid ± non-opioid ± adjuvants Neuropathic pain: Tramadol ± Gabapentin or pregabalin ± traditional antiepileptics Bone pain: NSAIDs Evaluate morphine equivalents treating patients on chronic opioid therapy | N/A | Emergency physicians need to feel comfortable with the use of morphine and morphine equivalents in managing pain both in the ED and when discharging patients home; palliative care benefits both the patient and the medical system at large: patients report a better quality of life and higher satisfaction when receiving palliative care services and medical costs are decreased. |

| Solberg, 2015 [37] | Review | To review the approach to palliative care in the Emergency Department | Patients worthy of palliative care, no age specification | NR | WHO analgesic ladder for nociceptive pain: mild pain (step 1) non-opioids ± adjuvants; moderate pain (step 2) weak opioids ± non-opioid ± adjuvants; severe pain (step 3) strong opioid ± non-opioid ± adjuvants | N/A | Currently, there is little research and evidence on the use of PC in the ED. However, one may infer patient satisfaction: other outcomes will improve and costs will be reduced, as they have in the inpatient setting. The systematic integration of PC into the ED is slowly occurring, as it is a recognised subspecialty of emergency medicine |

4. Discussion

4.1. Management of Pain at EOL in the ED in Clinical Practice

4.1.1. Identify Patient Worthy of End-of Life Care

4.1.2. Pain Assessment in EOL Patients in ED

4.1.3. Non-Pharmacological Management of Pain in EOL Patients

- −

- Setting: creating time, space, and resources for appropriate, uninterrupted communication with patients and their families.

- −

- Perception: asking first about illness awareness and severity.

- −

- Invitation: ensuring that the patient or family members are ready to discuss palliative or end-of-life care.

- −

- Knowledge: ensure that the patient or family members are aware of the disease context in which the pathology manifests.

- −

- Emotion: address emotions empathically; use the mnemonic NURSE [78] (Name the patient’s emotion, Understand the emotion through empathy, Respect the patient’s response, Support the patient, Explore the patient’s response, and inquire about the emotion).

- −

- Strategy: develop a plan for shared care.

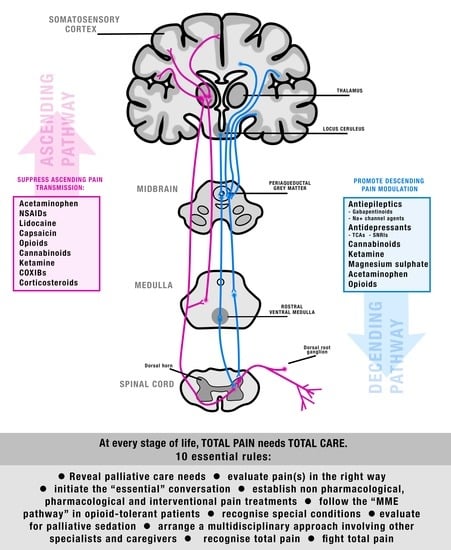

4.1.4. Pharmacological Management of Pain in EOL Patients

4.1.5. Special Situations: Rapid Pain Worsening in Chronic Pain

Breakthrough Pain

Opioid-Induced Hyperalgesia

4.1.6. Palliative Sedation

4.2. Limitations of the Present Narrative Review

5. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

Appendix A. Search Strategy according to Each Database

Appendix B

| Section and Topic | Item | Checklist Item | Location where Item is Reported |

|---|---|---|---|

| TITLE | |||

| Title | 1 | Identify the report as a systematic review. | Page 1, title |

| ABSTRACT | |||

| Abstract | 2 | See the PRISMA 2020 for Abstracts checklist. | Done, PRISMA 2020 abstract checklist included at the end of this checklist |

| INTRODUCTION | |||

| Rationale | 3 | Describe the rationale for the review in the context of existing knowledge. | Pages 2–3 |

| Objectives | 4 | Provide an explicit statement of the objective(s) or question(s) the review addresses. | Page 3, at the end of the introduction |

| METHODS | |||

| Eligibility criteria | 5 | Specify the inclusion and exclusion criteria for the review and how studies were grouped for the syntheses. | Page 3, Section 2.1 to page 4, Section 2.4 |

| Information sources | 6 | Specify all databases, registers, websites, organisations, reference lists and other sources searched or consulted to identify studies. Specify the date when each source was last searched or consulted. | Page 3, Section 2.2 |

| Search strategy | 7 | Present the full search strategies for all databases, registers and websites, including any filters and limits used. | Page 3, Section 2.2 and page 33, Appendix A |

| Selection process | 8 | Specify the methods used to decide whether a study met the inclusion criteria of the review, including how many reviewers screened each record and each report retrieved, whether they worked independently, and if applicable, details of automation tools used in the process. | Page 3, Section 2.2 |

| Data collection process | 9 | Specify the methods used to collect data from reports, including how many reviewers collected data from each report, whether they worked independently, any processes for obtaining or confirming data from study investigators, and if applicable, details of automation tools used in the process. | Page 3, Section 2.2 |

| Data items | 10a | List and define all outcomes for which data were sought. Specify whether all results that were compatible with each outcome domain in each study were sought (e.g., for all measures, time points, analyses), and if not, the methods used to decide which results to collect. | Page 4, Section 2.3 |

| 10b | List and define all other variables for which data were sought (e.g., participant and intervention characteristics, funding sources). Describe any assumptions made about any missing or unclear information. | Page 4, Section 2.3 | |

| Study risk of bias assessment | 11 | Specify the methods used to assess risk of bias in the included studies, including details of the tool(s) used, how many reviewers assessed each study and whether they worked independently, and if applicable, details of automation tools used in the process. | Not admitted |

| Effect measures | 12 | Specify for each outcome the effect measure(s) (e.g., risk ratio, mean difference) used in the synthesis or presentation of results. | Not admitted due to the narrative nature of the review |

| Synthesis methods | 13a | Describe the processes used to decide which studies were eligible for each synthesis (e.g., tabulating the study intervention characteristics and comparing against the planned groups for each synthesis (item #5)). | Page 4, Section 2.4 |

| 13b | Describe any methods required to prepare the data for presentation or synthesis, such as handling of missing summary statistics, or data conversions. | Page 4, Section 2.4 | |

| 13c | Describe any methods used to tabulate or visually display results of individual studies and syntheses. | Page 4, Section 2.4 | |

| 13d | Describe any methods used to synthesise results and provide a rationale for the choice(s). If meta-analysis was performed, describe the model(s), method(s) to identify the presence and extent of statistical heterogeneity, and software package(s) used. | Page 4, Section 2.4 | |

| 13e | Describe any methods used to explore possible causes of heterogeneity among study results (e.g., subgroup analysis, meta-regression). | Page 4, Section 2.4 | |

| 13f | Describe any sensitivity analyses conducted to assess robustness of the synthesised results. | Page 4, Section 2.4 | |

| Reporting bias assessment | 14 | Describe any methods used to assess risk of bias due to missing results in a synthesis (arising from reporting biases). | Not admitted |

| Certainty assessment | 15 | Describe any methods used to assess certainty (or confidence) in the body of evidence for an outcome. | Not admitted |

| RESULTS | |||

| Study selection | 16a | Describe the results of the search and selection process, from the number of records identified in the search to the number of studies included in the review, ideally using a flow diagram. | Page 4, Section 3.1 |

| 16b | Cite studies that might appear to meet the inclusion criteria, but which were excluded, and explain why they were excluded. | Page 4, Section 3.1 | |

| Study characteristics | 17 | Cite each included study and present its characteristics. | Page 4, Section 3.1 and page 6, Section 3.2 |

| Risk of bias in studies | 18 | Present assessments of risk of bias for each included study. | Not admitted |

| Results of individual studies | 19 | For all outcomes, present, for each study: (a) summary statistics for each group (where appropriate) and (b) an effect estimate and its precision (e.g., confidence/credible interval), ideally using structured tables or plots. | Page 4, Section 3.1 and page 9, Table 2 |

| Results of syntheses | 20a | For each synthesis, briefly summarise the characteristics and risk of bias among contributing studies. | Not admitted |

| 20b | Present results of all statistical syntheses conducted. If meta-analysis was conducted, present for each the summary estimate and its precision (e.g., confidence/credible interval) and measures of statistical heterogeneity. If comparing groups, describe the direction of the effect. | Not admitted | |

| 20c | Present results of all investigations of possible causes of heterogeneity among study results. | Page 6, Section 3.2 | |

| 20d | Present results of all sensitivity analyses conducted to assess the robustness of the synthesised results. | Not admitted | |

| Reporting biases | 21 | Present assessments of risk of bias due to missing results (arising from reporting biases) for each synthesis assessed. | Not admitted |

| Certainty of evidence | 22 | Present assessments of certainty (or confidence) in the body of evidence for each outcome assessed. | Page 15, discussion section |

| DISCUSSION | |||

| Discussion | 23a | Provide a general interpretation of the results in the context of other evidence. | Pages 15 and 16, discussion |

| 23b | Discuss any limitations of the evidence included in the review. | Pages 15 and 16, discussion | |

| 23c | Discuss any limitations of the review processes used. | Page 32, Section 4.2 | |

| 23d | Discuss implications of the results for practice, policy, and future research. | Page 32, Section 5 | |

| OTHER INFORMATION | |||

| Registration and protocol | 24a | Provide registration information for the review, including register name and registration number, or state that the review was not registered. | Page 33, registration |

| 24b | Indicate where the review protocol can be accessed, or state that a protocol was not prepared. | Not admitted | |

| 24c | Describe and explain any amendments to information provided at registration or in the protocol. | Not admitted | |

| Support | 25 | Describe sources of financial or non-financial support for the review and the role of the funders or sponsors in the review. | Page 33, acknowledgement and conflicts of interest |

| Competing interests | 26 | Declare any competing interests of review authors. | Page 33 |

| Availability of data, code and other materials | 27 | Report which of the following are publicly available and where they can be found: template data collection forms; data extracted from included studies; data used for all analyses; analytic code; any other materials used in the review. | Page 33 |

| Section and Topic | Item | Checklist Item | Reported (Yes/No) |

|---|---|---|---|

| TITLE | |||

| Title | 1 | Identify the report as a systematic review. | Yes (narrative review) |

| BACKGROUND | |||

| Objectives | 2 | Provide an explicit statement of the main objective(s) or question(s) the review addresses. | yes |

| METHODS | |||

| Eligibility criteria | 3 | Specify the inclusion and exclusion criteria for the review. | yes |

| Information sources | 4 | Specify the information sources (e.g., databases, registers) used to identify studies and the date when each was last searched. | yes |

| Risk of bias | 5 | Specify the methods used to assess risk of bias in the included studies. | Not admitted |

| Synthesis of results | 6 | Specify the methods used to present and synthesise results. | yes |

| RESULTS | |||

| Included studies | 7 | Give the total number of included studies and participants and summarise relevant characteristics of studies. | yes |

| Synthesis of results | 8 | Present results for main outcomes, preferably indicating the number of included studies and participants for each. If meta-analysis was conducted, report the summary estimate and confidence/credible interval. If comparing groups, indicate the direction of the effect (i.e., which group is favoured). | yes |

| DISCUSSION | |||

| Limitations of evidence | 9 | Provide a brief summary of the limitations of the evidence included in the review (e.g., study risk of bias, inconsistency and imprecision). | yes |

| Interpretation | 10 | Provide a general interpretation of the results and important implications. | yes |

| OTHER | |||

| Funding | 11 | Specify the primary source of funding for the review. | yes |

| Registration | 12 | Provide the register name and registration number. | yes |

References

- Smith, A.K.; Cenzer, I.S.; Knight, S.J.; Puntillo, K.A.; Widera, E.; Williams, B.A.; Boscardin, W.J.; Covinsky, K.E. The epidemiology of pain during the last 2 years of life. Ann. Intern. Med. 2010, 153, 563–569. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hagarty, A.M.; Bush, S.H.; Talarico, R.; Lapenskie, J.; Tanuseputro, P. Severe pain at the end of life: A population-level observational study. BMC Palliat. Care 2020, 19, 60. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Teunissen, S.C.; Wesker, W.; Kruitwagen, C.; de Haes, H.C.; Voest, E.E.; de Graeff, A. Symptom prevalence in patients with incurable cancer: A systematic review. J. Pain. Symptom Manag. 2007, 34, 94–104. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lee, A.L.; Harrison, S.L.; Goldstein, R.S.; Brooks, D. Pain and its clinical associations in individuals with COPD: A systematic review. Chest 2015, 147, 1246–1258. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Raina, R.; Krishnappa, V.; Gupta, M. Management of pain in end-stage renal disease patients: Short review. Hemodial. Int. 2018, 22, 290–296. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Peng, J.K.; Hepgul, N.; Higginson, I.J.; Gao, W. Symptom prevalence and quality of life of patients with end-stage liver disease: A systematic review and meta-analysis. Palliat. Med. 2019, 33, 24–36. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Goebel, J.R.; Doering, L.V.; Shugarman, L.R.; Asch, S.M.; Sherbourne, C.D.; Lanto, A.B.; Evangelista, L.S.; Nyamathi, A.M.; Maliski, S.L.; Lorenz, K.A. Heart failure: The hidden problem of pain. J. Pain. Symptom Manag. 2009, 38, 698–707. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Parker, R.; Stein, D.J.; Jelsma, J. Pain in people living with HIV/AIDS: A systematic review. J. Int. AIDS Soc. 2014, 17, 18719. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- De Tommaso, M.; Arendt-Nielsen, L.; Defrin, R.; Kunz, M.; Pickering, G.; Valeriani, M. Pain in Neurodegenerative Disease: Current Knowledge and Future Perspectives. Behav. Neurol. 2016, 2016, 7576292. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lawn, T.; Aman, Y.; Rukavina, K.; Sideris-Lampretsas, G.; Howard, M.; Ballard, C.; Ray Chaudhuri, K.; Malcangio, M. Pain in the neurodegenerating brain: Insights into pharmacotherapy for Alzheimer disease and Parkinson disease. Pain 2021, 162, 999–1006. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Raja, S.N.; Carr, D.B.; Cohen, M.; Finnerup, N.B.; Flor, H.; Gibson, S.; Keefe, F.J.; Mogil, J.S.; Ringkamp, M.; Sluka, K.A.; et al. The revised International Association for the Study of Pain definition of pain: Concepts, challenges, and compromises. Pain 2020, 161, 1976–1982. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Treede, R.D.; Rief, W.; Barke, A.; Aziz, Q.; Bennett, M.I.; Benoliel, R.; Cohen, M.; Evers, S.; Finnerup, N.B.; First, M.B.; et al. A classification of chronic pain for ICD-11. Pain 2015, 156, 1003–1007. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Clauw, D.J.; Essex, M.N.; Pitman, V.; Jones, K.D. Reframing chronic pain as a disease, not a symptom: Rationale and implications for pain management. Postgrad. Med. 2019, 131, 185–198. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chapman, C.R.; Tuckett, R.P.; Song, C.W. Pain and stress in a systems perspective: Reciprocal neural, endocrine, and immune interactions. J. Pain 2008, 9, 122–145. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lumley, M.A.; Cohen, J.L.; Borszcz, G.S.; Cano, A.; Radcliffe, A.M.; Porter, L.S.; Schubiner, H.; Keefe, F.J. Pain and emotion: A biopsychosocial review of recent research. J. Clin. Psychol. 2011, 67, 942–968. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Price, D.D. Psychological and neural mechanisms of the affective dimension of pain. Science 2000, 288, 1769–1772. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zaza, C.; Baine, N. Cancer pain and psychosocial factors: A critical review of the literature. J. Pain Symptom Manag. 2002, 24, 526–542. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Clark, D. ‘Total pain’, disciplinary power and the body in the work of Cicely Saunders, 1958–1967. Soc. Sci. Med. 1999, 49, 727–736. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Treede, R.D.; Rief, W.; Barke, A.; Aziz, Q.; Bennett, M.I.; Benoliel, R.; Cohen, M.; Evers, S.; Finnerup, N.B.; First, M.B.; et al. Chronic pain as a symptom or a disease: The IASP Classification of Chronic Pain for the International Classification of Diseases (ICD-11). Pain 2019, 160, 19–27. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Patel, P.M.; Goodman, L.F.; Knepel, S.A.; Miller, C.C.; Azimi, A.; Phillips, G.; Gustin, J.L.; Hartman, A. Evaluation of Emergency Department Management of Opioid-Tolerant Cancer Patients with Acute Pain. J. Pain Symptom Manag. 2017, 54, 501–507. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fortner, B.V.; Okon, T.A.; Portenoy, R.K. A survey of pain-related hospitalizations, emergency department visits, and physician office visits reported by cancer patients with and without history of breakthrough pain. J. Pain 2002, 3, 38–44. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Van den Beuken-Van Everdingen, M.H.; de Rijke, J.M.; Kessels, A.G.; Schouten, H.C.; van Kleef, M.; Patijn, J. Prevalence of pain in patients with cancer: A systematic review of the past 40 years. Ann. Oncol. 2007, 18, 1437–1449. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Van den Beuken-Van Everdingen, M.H.; Hochstenbach, L.M.; Joosten, E.A.; Tjan-Heijnen, V.C.; Janssen, D.J. Update on Prevalence of Pain in Patients with Cancer: Systematic Review and Meta-Analysis. J. Pain Symptom Manag. 2016, 51, 1070–1090.e9. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tricco, A.C.; Lillie, E.; Zarin, W.; O’Brien, K.K.; Colquhoun, H.; Levac, D.; Moher, D.; Peters, M.D.J.; Horsley, T.; Weeks, L.; et al. PRISMA Extension for Scoping Reviews (PRISMA-ScR): Checklist and Explanation. Ann. Intern. Med. 2018, 169, 467–473. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Australian Commission on Safety and Quality in Health Care. National Consensus Statement: Essential Elements for Safe and High-quality End-of-Life Care: Commonwealthwealth of Australia. 2015. Available online: https://www.safetyandquality.gov.au/sites/default/files/migrated/National-Consensus-Statement-Essential-Elements-forsafe-high-quality-end-of-life-care.pdf (accessed on 24 May 2023).

- WHO. Paliative Care. Available online: https://www.who.int/health-topics/palliative-care (accessed on 4 May 2023).

- Bennahum, D.A. Hospice and palliative care: Concepts and practice. In The Historical Development of Hospice and Palliative Care, 2nd ed.; Forman, W., Kitzes, J., Anderson, R.P., Eds.; Jones and Bartlett: Sudbury, MA, USA, 2003. [Google Scholar]

- Available online: https://www.iasp-pain.org/resources/terminology/ (accessed on 23 May 2023).

- Bell, D.; Ruttenberg, M.B.; Chai, E. Care of Geriatric Patients with Advanced Illnesses and End-of-Life Needs in the Emergency Department. Clin. Geriatr. Med. 2018, 34, 453–467. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chan, Y.C.; Yang, M.L.C.; Ho, H.F. Characteristics and Outcomes of Patients Referred to an Emergency Department-Based End-of-Life Care Service in Hong Kong: A Retrospective Cohort Study. Am. J. Hosp. Palliat. Care 2021, 38, 25–31. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Coyne, C.J.; Reyes-Gibby, C.C.; Durham, D.D.; Abar, B.; Adler, D.; Bastani, A.; Bernstein, S.L.; Baugh, C.W.; Bischof, J.J.; Grudzen, C.R.; et al. Cancer pain management in the emergency department: A multicenter prospective observational trial of the Comprehensive Oncologic Emergencies Research Network (CONCERN). Support. Care Cancer 2021, 29, 4543–4553. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- De Oliveira, R.; Lobato, C.B.; Maia-Moço, L.; Santos, M.; Neves, S.; Matos, M.F.; Cardoso, R.; Cruz, C.; Silva, C.A.; Dias, J.; et al. Palliative medicine in the emergency department: Symptom control and aggressive care. BMJ Support. Palliat. Care 2021. Online ahead of print. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lamba, S.; Quest, T.E. Hospice care and the emergency department: Rules, regulations, and referrals. Ann. Emerg. Med. 2011, 57, 282–290. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Long, D.A.; Koyfman, A.; Long, B. Oncologic Emergencies: Palliative Care in the Emergency Department Setting. J. Emerg. Med. 2021, 60, 175–191. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rojas, E.; Schultz, R.; Linsalata, H.H.; Sumberg, D.; Christensen, M.; Robinson, C.; Rosenberg, M. Implementation of a Life-Sustaining Management and Alternative Protocol for Actively Dying Patients in the Emergency Department. J. Emerg. Nurs. 2016, 42, 201–206. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Siegel, M.; Bigelow, S. Palliative Care Symptom Management in The Emergency Department: The ABC’s of Symptom Management for The Emergency Physician. J. Emerg. Med. 2018, 54, 25–32. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Solberg, L.M.; Hincapie-Echeverri, J. Palliative Care in the Emergency Department. Crit. Care Nurs. Clin. N. Am. 2015, 27, 355–368. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- American College of Emergency Physicians. Ethical issues in emergency department care at the end of life. Ann. Emerg. Med. 2006, 47, 302. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- APSOC. Declaration of Montreal. Available online: https://www.apsoc.org.au/PDF/Publications/DeclarationOfMontreal_IASP.pdf (accessed on 24 May 2023).

- Quest, T.E.; Marco, C.A.; Derse, A.R. Hospice and palliative medicine: New subspecialty, new opportunities. Ann. Emerg. Med. 2009, 54, 94–102. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Huang, Y.L.; Alsaba, N.; Brookes, G.; Crilly, J. Review article: End-of-life care for older people in the emergency department: A scoping review. Emerg. Med. Australas 2020, 32, 7–19. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Beynon, T.; Gomes, B.; Murtagh, F.E.; Glucksman, E.; Parfitt, A.; Burman, R.; Edmonds, P.; Carey, I.; Keep, J.; Higginson, I.J. How common are palliative care needs among older people who die in the emergency department? Emerg. Med. J. 2011, 28, 491–495. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Glajchen, M.; Lawson, R.; Homel, P.; Desandre, P.; Todd, K.H. A rapid two-stage screening protocol for palliative care in the emergency department: A quality improvement initiative. J. Pain Symptom Manag. 2011, 42, 657–662. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yash Pal, R.; Kuan, W.S.; Koh, Y.; Venugopal, K.; Ibrahim, I. Death among elderly patients in the emergency department: A needs assessment for end-of-life care. Singap. Med. J. 2017, 58, 129–133. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- De Decker, L.; Beauchet, O.; Gouraud-Tanguy, A.; Berrut, G.; Annweiler, C.; Le Conte, P. Treatment-limiting decisions, comorbidities, and mortality in the emergency departments: A cross-sectional elderly population-based study. J. Nutr. Health Aging 2012, 16, 914–918. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Aldeen, A.Z.; Courtney, D.M.; Lindquist, L.A.; Dresden, S.M.; Gravenor, S.J. Geriatric emergency department innovations: Preliminary data for the geriatric nurse liaison model. J. Am. Geriatr. Soc. 2014, 62, 1781–1785. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Salvi, F.; Morichi, V.; Grilli, A.; Spazzafumo, L.; Giorgi, R.; Polonara, S.; De Tommaso, G.; Dessì-Fulgheri, P. Predictive validity of the Identification of Seniors at Risk (ISAR) screening tool in elderly patients presenting to two Italian Emergency Departments. Aging Clin. Exp. Res. 2009, 21, 69–75. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mahony, S.O.; Blank, A.; Simpson, J.; Persaud, J.; Huvane, B.; McAllen, S.; Davitt, M.; McHugh, M.; Hutcheson, A.; Karakas, S.; et al. Preliminary report of a palliative care and case management project in an emergency department for chronically ill elderly patients. J. Urban. Health 2008, 85, 443–451. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Grudzen, C.; Richardson, L.D.; Baumlin, K.M.; Winkel, G.; Davila, C.; Ng, K.; Hwang, U.; GEDI WISE Investigators. Redesigned geriatric emergency care may have helped reduce admissions of older adults to intensive care units. Health Aff. 2015, 34, 788–795. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cardona, M.; Lewis, E.T.; Kristensen, M.R.; Skjøt-Arkil, H.; Ekmann, A.A.; Nygaard, H.H.; Jensen, J.J.; Jensen, R.O.; Pedersen, J.L.; Turner, R.M.; et al. Predictive validity of the CriSTAL tool for short-term mortality in older people presenting at Emergency Departments: A prospective study. Eur. Geriatr. Med. 2018, 9, 891–901. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cardona, M.; O’Sullivan, M.; Lewis, E.T.; Turner, R.M.; Garden, F.; Alkhouri, H.; Asha, S.; Mackenzie, J.; Perkins, M.; Suri, S.; et al. Prospective Validation of a Checklist to Predict Short-term Death in Older Patients After Emergency Department Admission in Australia and Ireland. Acad. Emerg. Med. 2019, 26, 610–620. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ouchi, K.; Jambaulikar, G.; George, N.R.; Xu, W.; Obermeyer, Z.; Aaronson, E.L.; Schuur, J.D.; Schonberg, M.A.; Tulsky, J.A.; Block, S.D. The “Surprise Question” Asked of Emergency Physicians May Predict 12-Month Mortality among Older Emergency Department Patients. J. Palliat. Med. 2018, 21, 236–240. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gómez-Batiste, X.; Martínez-Muñoz, M.; Blay, C.; Amblàs, J.; Vila, L.; Costa, X. Identificación de personas con enfermedades crónicas avanzadas y necesidad de atención paliativa en servicios sanitarios y sociales: Elaboración del instrumento NECPAL CCOMS-ICO(©) [Identification of people with chronic advanced diseases and need of palliative care in sociosanitary services: Elaboration of the NECPAL CCOMS-ICO© tool]. Med. Clin. 2013, 140, 241–245. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- George, N.; Barrett, N.; McPeake, L.; Goett, R.; Anderson, K.; Baird, J. Content Validation of a Novel Screening Tool to Identify Emergency Department Patients with Significant Palliative Care Needs. Acad. Emerg. Med. 2015, 22, 823–837. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Maas, E.A.; Murray, S.A.; Engels, Y.; Campbell, C. What tools are available to identify patients with palliative care needs in primary care: A systematic literature review and survey of European practice. BMJ Support. Palliat. Care 2013, 3, 444–451. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Reuter, Q.; Marshall, A.; Zaidi, H.; Sista, P.; Powell, E.S.; McCarthy, D.M.; Dresden, S.M. Emergency Department-Based Palliative Interventions: A Novel Approach to Palliative Care in the Emergency Department. J. Palliat. Med. 2019, 22, 649–655. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Charles, C.; Gafni, A.; Whelan, T. Shared decision-making in the medical encounter: What does it mean? (or it takes at least two to tango). Soc. Sci. Med. 1997, 44, 681–692. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Gawande, A. Being Mortal. Illness, Medicine and What Matters in the End; Profile Books: London, UK, 2015. [Google Scholar]

- Reeves, K. Hospice care in the emergency department: Important things to remember. J. Emerg. Nurs. 2000, 26, 477–528. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bennett, M.I.; Kaasa, S.; Barke, A.; Korwisi, B.; Rief, W.; Treede, R.D.; IASP Taskforce for the Classification of Chronic Pain. The IASP classification of chronic pain for ICD-11: Chronic cancer-related pain. Pain 2019, 160, 38–44. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Loeser, J.D. A new way of thinking about pains. Pain 2022, 163, 1670–1674. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Williamson, A.; Hoggart, B. Pain: A review of three commonly used pain rating scales. J. Clin. Nurs. 2005, 14, 798–804. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hicks, C.L.; von Baeyer, C.L.; Spafford, P.A.; van Korlaar, I.; Goodenough, B. The Faces Pain Scale-Revised: Toward a common metric in pediatric pain measurement. Pain 2001, 93, 173–183. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tan, G.; Jensen, M.P.; Thornby, J.I.; Shanti, B.F. Validation of the Brief Pain Inventory for chronic nonmalignant pain. J. Pain 2004, 5, 133–137. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Melzack, R. The short-form McGill Pain Questionnaire. Pain 1987, 30, 191–197. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bennett, M. The LANSS Pain Scale: The Leeds assessment of neuropathic symptoms and signs. Pain 2001, 92, 147–157. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Galer, B.S.; Jensen, M.P. Development and preliminary validation of a pain measure specific to neuropathic pain: The Neuropathic Pain Scale. Neurology 1997, 48, 332–338. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Crellin, D.J.; Harrison, D.; Santamaria, N.; Babl, F.E. Systematic review of the Face, Legs, Activity, Cry and Consolability scale for assessing pain in infants and children: Is it reliable, valid, and feasible for use? Pain 2015, 156, 2132–2151. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Warden, V.; Hurley, A.C.; Volicer, L. Development and psychometric evaluation of the Pain Assessment in Advanced Dementia (PAINAD) scale. J. Am. Med. Dir. Assoc. 2003, 4, 9–15. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Gélinas, C.; Fortier, M.; Viens, C.; Fillion, L.; Puntillo, K. Pain assessment and management in critically ill intubated patients: A retrospective study. Am. J. Crit. Care 2004, 13, 126–135. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- EUSEM. Guidelines for the Management of Acute Pain in Emergency Situations. Available online: https://www.eusem.org/images/EUSEM_EPI_GUIDELINES_MARCH_2020.pdf (accessed on 24 May 2023).

- Savoia, G.; Coluzzi, F.; Di Maria, C.; Ambrosio, F.; Della Corte, F.; Oggioni, R.; Messina, A.; Costantini, A.; Launo, C.; Mattia, C. Italian Intersociety Recommendations on pain management in the emergency setting (SIAARTI, SIMEU, SIS 118, AISD, SIARED, SICUT, IRC). Minerva Anestesiol 2015, 81, 205–225. [Google Scholar]

- EFIC. What Is the Biopsychosocial Model of Pain? Available online: https://europeanpainfederation.eu/what-is-the-bio-psycho-social-model-of-pain/ (accessed on 24 May 2023).

- Powell, R.; Scott, N.W.; Manyande, A.; Bruce, J.; Vögele, C.; Byrne-Davis, L.M.; Unsworth, M.; Osmer, C.; Johnston, M. Psychological preparation and postoperative outcomes for adults undergoing surgery under general anaesthesia. Cochrane Database Syst. Rev. 2016, 2016, CD008646. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Suls, J.; Wan, C.K. Effects of sensory and procedural information on coping with stressful medical procedures and pain: A meta-analysis. J. Consult. Clin. Psychol. 1989, 57, 372–379. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sallnow, L.; Smith, R.; Ahmedzai, S.H.; Bhadelia, A.; Chamberlain, C.; Cong, Y.; Doble, B.; Dullie, L.; Durie, R.; Finkelstein, E.A.; et al. Report of the Lancet Commission on the Value of Death: Bringing death back into life. Lancet 2022, 399, 837–884. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Baile, W.F.; Buckman, R.; Lenzi, R.; Glober, G.; Beale, E.A.; Kudelka, A.P. SPIKES-A six-step protocol for delivering bad news: Application to the patient with cancer. Oncologist 2000, 5, 302–311. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fischer, G.; Tulsky, J.; Arnold, R. Communicating a poor prognosis. In Topics in Palliative Care; Portenoy, R., Bruera, E., Eds.; Oxford University Press: New York, NY, USA, 2000; pp. 75–89. [Google Scholar]

- Coelho, A.; Parola, V.; Cardoso, D.; Bravo, M.E.; Apóstolo, J. Use of non-pharmacological interventions for comforting patients in palliative care: A scoping review. JBI Database Syst. Rev. Implement. Rep. 2017, 15, 1867–1904. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Davies, A.N.; Dickman, A.; Reid, C.; Stevens, A.M.; Zeppetella, G.; Science Committee of the Association for Palliative Medicine of Great Britain and Ireland. The management of cancer-related breakthrough pain: Recommendations of a task group of the Science Committee of the Association for Palliative Medicine of Great Britain and Ireland. Eur. J. Pain 2009, 13, 331–338. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Poggiali, E.; Bertè, R.; Orsi, L. When emergency medicine embraces palliative care. Emerg. Care J. 2022, 18. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ventafridda, V.; Saita, L.; Ripamonti, C.; De Conno, F. WHO guidelines for the use of analgesics in cancer pain. Int. J. Tissue React. 1985, 7, 93–96. [Google Scholar]

- Meldrum, M. The ladder and the clock: Cancer pain and public policy at the end of the twentieth century. J. Pain Symptom Manag. 2005, 29, 41–54. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Davis, M.P.; Weissman, D.E.; Arnold, R.M. Opioid dose titration for severe cancer pain: A systematic evidence-based review. J. Palliat. Med. 2004, 7, 462–468. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Barakzoy, A.S.; Moss, A.H. Efficacy of the world health organization analgesic ladder to treat pain in end-stage renal disease. J. Am. Soc. Nephrol. 2006, 17, 3198–3203. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jadad, A.R.; Browman, G.P. The WHO analgesic ladder for cancer pain management. Stepping up the quality of its evaluation. JAMA 1995, 274, 1870–1873. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Attal, N.; Cruccu, G.; Baron, R.; Haanpää, M.; Hansson, P.; Jensen, T.S.; Nurmikko, T. EFNS guidelines on the pharmacological treatment of neuropathic pain: 2010 revision. Eur. J. Neurol. 2010, 17, 1113-e88. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vadalouca, A.; Moka, E.; Argyra, E.; Sikioti, P.; Siafaka, I. Opioid rotation in patients with cancer: A review of the current literature. J. Opioid Manag. 2008, 4, 213–250. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Szeto, C.C.; Sugano, K.; Wang, J.G.; Fujimoto, K.; Whittle, S.; Modi, G.K.; Chen, C.H.; Park, J.B.; Tam, L.S.; Vareesangthip, K.; et al. Non-steroidal anti-inflammatory drug (NSAID) therapy in patients with hypertension, cardiovascular, renal or gastrointestinal comorbidities: Joint APAGE/APLAR/APSDE/APSH/APSN/PoA recommendations. Gut 2020, 69, 617–629. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Magee, D.J.; Jhanji, S.; Poulogiannis, G.; Farquhar-Smith, P.; Brown, M.R.D. Nonsteroidal anti-inflammatory drugs and pain in cancer patients: A systematic review and reappraisal of the evidence. Br. J. Anaesth 2019, 123, e412–e423. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Derry, S.; Wiffen, P.J.; Moore, R.A.; McNicol, E.D.; Bell, R.F.; Carr, D.B.; McIntyre, M.; Wee, B. Oral nonsteroidal anti-inflammatory drugs (NSAIDs) for cancer pain in adults. Cochrane Database Syst. Rev. 2017, 7, CD012638. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Anekar, A.A.; Cascella, M. WHO Analgesic Ladder. In StatPearls; StatPearls Publishing: Treasure Island, FL, USA, 2023. [Google Scholar]

- Cuomo, A.; Bimonte, S.; Forte, C.A.; Botti, G.; Cascella, M. Multimodal approaches and tailored therapies for pain management: The trolley analgesic model. J. Pain. Res. 2019, 12, 711–714. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Davis, M.P.; Walsh, D.; Lagman, R.; LeGrand, S.B. Controversies in pharmacotherapy of pain management. Lancet Oncol. 2005, 6, 696–704. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Cruccu, G.; Truini, A. A review of Neuropathic Pain: From Guidelines to Clinical Practice. Pain. Ther. 2017, 6 (Suppl. S1), 35–42. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wiffen, P.J.; Derry, S.; Moore, R.A.; Lunn, M.P. Levetiracetam for neuropathic pain in adults. Cochrane Database Syst. Rev. 2014, 2014, CD010943. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Gill, D.; Derry, S.; Wiffen, P.J.; Moore, R.A. Valproic acid and sodium valproate for neuropathic pain and fibromyalgia in adults. Cochrane Database Syst. Rev. 2011, 2011, CD009183. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wiffen, P.J.; Derry, S.; Moore, R.A. Lamotrigine for acute and chronic pain. Cochrane Database Syst. Rev. 2011, CD006044. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Riccardi, A.; Guarino, M.; Serra, S.; Spampinato, M.D.; Vanni, S.; Shiffer, D.; Voza, A.; Fabbri, A.; De Iaco, F.; Study and Research Center of the Italian Society of Emergency Medicine. Narrative Review: Low-Dose Ketamine for Pain Management. J. Clin. Med. 2023, 12, 3256. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Albrecht, E.; Kirkham, K.R.; Liu, S.S.; Brull, R. Peri-operative intravenous administration of magnesium sulphate and postoperative pain: A meta-analysis. Anaesthesia 2013, 68, 79–90. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tramer, M.R.; Schneider, J.; Marti, R.A.; Rifat, K. Role of magnesium sulfate in postoperative analgesia. Anesthesiology 1996, 84, 340–347. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Morel, V.; Pickering, M.E.; Goubayon, J.; Djobo, M.; Macian, N.; Pickering, G. Magnesium for Pain Treatment in 2021? State of the Art. Nutrients 2021, 13, 1397. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Vyvey, M. Steroids as pain relief adjuvants. Can. Fam. Physician 2010, 56, 1295-e415. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Eker, H.E.; Cok, O.Y.; Aribogan, A.; Arslan, G. Management of neuropathic pain with methylprednisolone at the site of nerve injury. Pain Med. 2012, 13, 443–451. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Mitra, R.; Jones, S. Adjuvant analgesics in cancer pain: A review. Am. J. Hosp. Palliat. Care 2012, 29, 70–79. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Up to Date. Available online: https://www.uptodate.com/contents/search (accessed on 23 May 2023).

- Drug Bank. Available online: https://go.drugbank.com/accessed (accessed on 23 May 2023).

- Bhaskar, A. Interventional pain management in patients with cancer-related pain. Postgrad. Med. 2020, 132 (Suppl. S3), 13–16. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hochberg, U.; Minerbi, A.; Boucher, L.M.; Perez, J. Interventional Pain Management for Cancer Pain: An Analysis of Outcomes and Predictors of Clinical Response. Pain Physician 2020, 23, E451–E460. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Klepstad, P.; Kurita, G.P.; Mercadante, S.; Sjøgren, P. Evidence of peripheral nerve blocks for cancer-related pain: A systematic review. Minerva Anestesiol 2015, 81, 789–793. [Google Scholar]

- Portenoy, K.R.; Copenhaver, M.D. Cancer pain management: Interventional therapies. In UpToDate; Post, T.W., Ed.; UpToDate: Waltham, MA, USA, 2023. [Google Scholar]

- Abdelhamid, K.; ElHawary, H.; Turner, J.P. The Use of the Erector Spinae Plane Block to Decrease Pain and Opioid Consumption in the Emergency Department: A Literature Review. J. Emerg. Med. 2020, 58, 603–609. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Goldsmith, A.J.; Liteplo, A.S.; Shokoohi, H. Ultrasound-Guided Serratus Anterior Plane Block for Intractable Herpes Zoster Pain in the Emergency Department. J. Emerg. Med. 2020, 59, 409–412. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ritcey, B.; Pageau, P.; Woo, M.Y.; Perry, J.J. Regional Nerve Blocks for Hip and Femoral Neck Fractures in the Emergency Department: A Systematic Review. CJEM 2016, 18, 37–47. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- De Iaco, F.; Mannaioni, G.; Serra, S.; Finco, G.; Sartori, S.; Gandolfo, E.; Sansone, P.; Marinangeli, F. Equianalgesia, opioid switch and opioid association in different clinical settings: A narrative review. Eur. Rev. Med. Pharmacol. Sci. 2022, 26, 2000–2017. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Mercadante, S.; Radbruch, L.; Caraceni, A.; Cherny, N.; Kaasa, S.; Nauck, F.; Ripamonti, C.; De Conno, F.; Steering Committee of the European Association for Palliative Care (EAPC) Research Network. Episodic (breakthrough) pain: Consensus conference of an expert working group of the European Association for Palliative Care. Cancer 2002, 94, 832–839. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Caraceni, A.; Hanks, G.; Kaasa, S.; Bennett, M.I.; Brunelli, C.; Cherny, N.; Dale, O.; De Conno, F.; Fallon, M.; Hanna, M. Use of opioid analgesics in the treatment of cancer pain: Evidence-based recommendations from the EAPC. Lancet Oncol. 2012, 13, e58–e68. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Cherny, N.I.; ESMO Guidelines Working Group. ESMO Clinical Practice Guidelines for the management of refractory symptoms at the end of life and the use of palliative sedation. Ann. Oncol. 2014, 25 (Suppl. S3), iii143–iii152. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- De Graeff, A.; Dean, M. Palliative sedation therapy in the last weeks of life: A literature review and recommendations for standards. J. Palliat. Med. 2007, 10, 67–85. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Materstvedt, L.J.; Clark, D.; Ellershaw, J.; Førde, R.; Gravgaard, A.M.; Müller-Busch, H.C.; Porta i Sales, J.; Rapin, C.H.; EAPC Ethics Task Force. Euthanasia and physician-assisted suicide: A view from an EAPC Ethics Task Force. Palliat. Med. 2003, 17, 97–179. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Juth, N.; Lindblad, A.; Lynöe, N.; Sjöstrand, M.; Helgesson, G. European Association for Palliative Care (EAPC) framework for palliative sedation: An ethical discussion. BMC Palliat. Care 2010, 9, 20. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Surges, S.M.; Garralda, E.; Jaspers, B.; Brunsch, H.; Rijpstra, M.; Hasselaar, J.; Van der Elst, M.; Menten, J.; Csikós, Á.; Mercadante, S. Review of European Guidelines on Palliative Sedation: A Foundation for the Updating of the European Association for Palliative Care Framework. J. Palliat. Med. 2022, 25, 1721–1731. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Beller, E.M.; van Driel, M.L.; McGregor, L.; Truong, S.; Mitchell, G. Palliative pharmacological sedation for terminally ill adults. Cochrane Database Syst. Rev. 2015, 1, CD010206. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Maltoni, M.; Pittureri, C.; Scarpi, E.; Piccinini, L.; Martini, F.; Turci, P.; Montanari, L.; Nanni, O.; Amadori, D. Palliative sedation therapy does not hasten death: Results from a prospective multicenter study. Ann. Oncol. 2009, 20, 1163–1169. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Yokomichi, N.; Yamaguchi, T.; Maeda, I.; Mori, M.; Imai, K.; Shirado Naito, A.; Yamaguchi, T.; Terabayashi, T.; Hiratsuka, Y.; Hisanaga, T.; et al. Effect of continuous deep sedation on survival in the last days of life of cancer patients: A multicenter prospective cohort study. Palliat. Med. 2022, 36, 189–199. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Cherny, N.I.; Radbruch, L.; Board of the European Association for Palliative Care. European Association for Palliative Care (EAPC) recommended framework for the use of sedation in palliative care. Palliat. Med. 2009, 23, 581–593. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Garetto, F.; Cancelli, F.; Rossi, R.; Maltoni, M. Palliative Sedation for the Terminally Ill Patient. CNS Drugs 2018, 32, 951–961. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- SIAARTI—Italian Society of Anaesthesia Analgesia Resuscitation and Intensive Care Bioethical Board. End-of-life care and the intensivist: SIAARTI recommendations on the management of the dying patient. Minerva Anestesiol 2006, 72, 927–963. [Google Scholar]

- McEwan, A.; Silverberg, J.Z. Palliative Care in the Emergency Department. Emerg. Med. Clin. N. Am. 2016, 34, 667–685. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- McWilliams, K.; Keeley, P.W.; Waterhouse, E.T. Propofol for terminal sedation in palliative care: A systematic review. J. Palliat. Med. 2010, 13, 73–76. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gaertner, J.; Fusi-Schmidhauser, T. Dexmedetomidine: A magic bullet on its way into palliative care-a narrative review and practice recommendations. Ann. Palliat. Med. 2022, 11, 1491–1504. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mercadante, S. The use of remifentanil in palliative care. J. Pain Symptom Manag. 1999, 17, 387–388. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Goldman, N.; Frankenthaler, M.; Klepacz, L. The Efficacy of Ketamine in the Palliative Care Setting: A Comprehensive Review of the Literature. J. Palliat. Med. 2019, 22, 1154–1161. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Page, M.J.; McKenzie, J.E.; Bossuyt, P.M.; Boutron, I.; Hoffmann, T.C.; Mulrow, C.D.; Shamseer, L.; Tetzlaff, J.M.; Akl, E.A.; Brennan, S.E.; et al. The PRISMA 2020 statement: An updated guideline for reporting systematic reviews. BMJ 2021, 372, n71. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

| Terms | Definition |

|---|---|

| Pain | An unpleasant sensory and emotional experience associated with, or resembling that associated with, actual or potential tissue damage. |

| Allodynia | Pain to stimulus that does not normally provoke pain, leading to an unexpectedly painful response. |

| Hyperalgesia | Increased pain from a stimulus that normally provokes pain. |

| Neuralgia | Pain in the distribution of a nerve or nerves. |

| Neuropathy | A disturbance of function or pathological change in a nerve or in several nerves. |

| Nociception | The neural process of encoding noxious stimuli. |

| Nociceptive pain | Pain that arises from actual or threatened damage to non-neural tissue and is due to the activation of nociceptors. |

| Neuropathic pain | Pain caused by a lesion or disease of the somatosensory nervous system. |

| Central neuropathy pain | Pain caused by a lesion or disease of the central somatosensory nervous system. |

| Peripheral neuropathic pain | Pain caused by a lesion or disease of the peripheral somatosensory nervous system. |

| Nociplastic pain | Pain that arises from altered nociception despite no clear evidence of actual or threatened tissue damage causing the activation of peripheral nociceptors or evidence for disease or lesion of the somatosensory system causing the pain. |

| Scale | Items Evaluated | |

|---|---|---|

| Unidimensional pain evaluation: | ||

| Numerical Rating Scale, NRS | 0 for “no pain” to 10 for “worst pain”, verbally reported | |

| Visual Analogue Scale, VAS | A scale from 0 to 10 is reported on a paper sheet, and the patient needs to mark the level of pain in this scale | |

| Faces Pain Scale Revised | 6 different facial expressions (from a smile to intense crying) are depicted and the patients should choose the most appropriate to describe pain intensity | |

| Multidimensional pain evaluation: | ||

| The Brief Pain Inventory, BPI | 1. Presence of other types of pain 2. Sign areas of pain in the body With a number from 0 to 10: Rate the worst pain in the last 24 h Rate the least pain in the last 24 h Rate the average pain Rate the actual pain Enlist the medications used for pain management Rate how much relief pain medication provided Rate how much pain interfered with: general activity, mood, walking, normal work, relations with other people, sleep, enjoyment of life. | |

| The Short-Form McGill Pain Questionnaire, SF-MPQ | Compiled by the patients, which has to rate as none (0), mild (1), moderate (2) more severe (3) the presence of: Throbbing, Shooting, Stabbing, Sharp, Cramping, Gnawing, Hot/burning, Aching, Heavy, Tender, Spitting, Tiring/Exhausting, Sickening, Fearful, Punishing/Cruel | |

| Edmonton Symptom Assessment System | Compiled by the patient, who has to rate from 0 to 10 how he felt in the last 24 h about: pain; tired, nauseated, depressed, anxious, drowsy, appetite, well-being, shortness of breath, abdominal discomfort, able to move normally | |

| Neuropathic pain: | ||

| Leeds Assessment of Neuropathic Symptoms and Signs (LANSS) | Evaluate the presence or absence of: (I) unpleasant sensations described as pricking, tingling or pins in skin in pain area, skin abnormally sensitive to touch, pain coming suddenly and in burst, sensation of skin temperature altered; (II) objectively tasted: presence of allodynia (different reactions to soft touch in painful and non-painful areas); altered pinprick threshold | |

| Neuropathic Pain Scale (NPS) | The patient has to rate via VAS the presence of: burning pain; overly sensitive to touch, shooting pain, numbness, electric pain, tingling pain, squeezing pain, freezing pain, how unpleasant is usual pain, how overwhelming is usual pain | |

| Non-cooperative or cognitively impaired patients | ||

| Face Leg Activity Cry Consolability, FLACC | Observer scores from 0 to 2 for the presence of abnormal: face expression, legs position, activity, cry, consolability | |

| Pain Assessment in Advanced Dementia, PAINAD | Observer scores from 0 to 2 for the presence of abnormal: breathing, negative vocalisation, facial expression, body language, consolability | |

| Critical Care Pain Observation Tool | Observer scores from 0 to 2 for the compliance with the ventilator in case of an intubated patient, facial expression, body movements, muscle tension | |

| Medication | Mechanism of Action | Dosing | Onset, Peak of Effect, Duration | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Nociceptive pain | ||||

| Mild | ||||

| Acetaminophen | Unclear mechanism of action, activation of descending serotonergic inhibitory pathways in the CNS may be a component, COX-1, COX-2, CO-3 inhibition | IV: maximum dose of 4 g/day, 1 g every six hours Patients <50 kg or with chronic alcoholism, malnutrition, or dehydration: 12.5 mg/kg every four hours or 15 mg/kg every six hours, maximum 750 mg/dose, maximum 3.75 g/day | Onset: oral <1 h, IV: 5–10 min Peak of action: UV; 1 h Duration: oral, IV: 4–6 h | |

| Nonsteroidal anti-inflammatory drugs | Ibuprofen | COX-1 and COX-2 reversible inhibition; reduced prostaglandin formation | PO 200 to 800 mg 3–4 times daily IV 400 to 800 mg every 6 h as needed, up to 3200 mg in acute phase | Onset: PO: 30–60 min Peak: PO: ND Duration:: PO: ND |

| Ketorolac | PO ≥ 50 kg: 20 mg PO, followed by 10 mg every 4–6 h as needed IV ≥ 50 kg: 30 mg IV as a single dose or 30 mg every 6 h | Onset: 30 min Peak: 2–3 h Duration: 4–6 h | ||

| COX-2 selective NSAIDs | Celecoxib | COX-2 inhibition, with decreased prostaglandin precursors formation | PO: 200 mg daily or 100 mg every 12 h, maximum dose: 400 mg per day | Onset: ND Peak: capsule: 3 h, oral solution: 0.7–1 h Duration: ND. Half-life elimination: 0.7–1 h |

| Eterocoxib | PO: 30 to 60 mg once daily, maximum dose: 120 mg in acute pain, up to 8 days, 60 mg otherwise | Onset: ND Peak: 1 h Duration: ND | ||

| Moderate | ||||

| Opioids | Codeine | Mu-, delta-, kappa-opioid receptors agonist; inhibition of ascending pain pathways and altered perception and response to pain | 30 to 60 mg every 4 to 6 h as needed | Onset: 0.5–1 h Peak: 1–1.5 h Duration: 4–6 h |

| Tapentadol | Mu-opioid receptors agonist, sodium-dependent noradrenaline transporter inhibitor; inhibition of ascending pain pathways and altered perception and response to pain | PO 50 to 100 mg every 4 to 6 h as needed; maximum total daily dose: 600 mg/day. | Onset: 1.25 h Peak: 1.25 h, long acting formulations: 3–6 h Duration: ND, half-life elimination: 4 h, long acting formulations: 5–6 h Peak: Immediate release: 1.25 h; Long-acting formulations: 3–6 h Duration 4–6 h | |

| Severe | ||||

| Opioids | Fentanyl | Mu-, delta-opiate receptors agonist at many sites within the CNS; increases pain threshold, alters pain perception and inhibits ascending pain pathways | IN: 1.5–2 mcg/kg IM: 50–100 mcg every 1–2 h as needed (only if IV not available) IV: 50–100 mcg every 30–60 min (1.0 mcg/kg) or 1–3 mcg/kg Acute pain in patients on chronic opioid therapy (e.g., breakthrough cancer pain): transmucosal: buccal tablet: 100 mcg, IN: 100 mcg, sublingual spray: 100 mcg, IV: see main text for specific dosing | Onset: IN: 5 to 10 min; IM: 7 to 8 min; IV: Almost immediate; Transdermal patch (initial placement): 6 h; Transmucosal: 5 to 15 min. Peak: Intranasal: 15–21 min Transdermal patch: 20–72 h Duration: IM: 1 to 2 h; IV: 0.5 to 1 h; Transdermal (removal of patch/no replacement): Related to blood level; some effects may last 72 to 96 h due to extended half-life and absorption from the skin, fentanyl concentrations decrease by ~50% in 20 to 27 h; Transmucosal: Related to blood level |

| Morphine | Mu-, kappa-, delta-opiate receptors agonist; inhibition of ascending pain pathways, alters perception and response to pain, CNS depression | IV: 4 mg every 2 h (0.1 mg/kg), 2–5 mg IV every 15 min titrated to pain relief Acute pain in patients on chronic opioid therapy (e.g., breakthrough cancer pain): calculate the 24 h MME using appropriate opioids equivalent chart, administer 15% of the total dose IV. Repeat as needed | Onset: Oral (immediate release): ~30 min; IV: 5 to 10 min. Peak: Oral: 1 h, IM: 30–60 min, IV: 20 min, SUBQ: 50–90 min Duration: Immediate-release formulations (tablet, oral solution, injection): 3 to 5 h, extended release: 8–24 h; IV half-life elimination: 2–4 h | |

| Hydromorphone | Mu-, kappa-opioid receptor agonist, delta-opioid receptor partial agonist | IV: 0.4–1 mg every 2–4 h (mg/kg) | Onset: Oral: 15–30 min, IV: 5 min Peak: Oral: 30–60 min, IV: 10–20 min Duration: 3–4 h | |

| Oxycodone | Mu-, kappa-, delta-opioid receptor | Oral: Initial: 5 mg every 4 to 6 h as needed Usual dosage range: 5 to 15 mg every 4 to 6 h as needed Acute pain in patients on chronic opioid therapy (e.g., breakthrough cancer pain): Immediate release: Oral. Usual dose: In conjunction with the scheduled opioid, administer 5% to 15% (rarely up to 20%) of the 24 h oxycodone requirement (or morphine milligram equivalents) as needed using an immediate release formulation every 4 to 6 h with subsequent dosage adjustments based upon response | Onset: 10–15 min Peak: 0.5–1 h Duration: 3–6 h | |

| Non-opioids | Ketamine | Glutamate receptor ionotropic NMDA 3A, antagonist, 5-hydroxytryptamine receptor 3A potentiator, alpha-7 nicotinic cholinergic receptor subunit antagonist, cholinesterase inhibitor, nitric oxide synthase inhibitor; analgesia, modulate central sensitisation, hyperalgesia and opioid tolerance | IV: 0.1–0.3 mg/kg bolus; 0.1–0.3 mg/kg/hours via continuous infusion | Onset: IV: 10–15 min, IN: 10 min Peak: IN: 10–15 min, Duration: IV: 30 min, IN: 60 min. |

| Neuropathic pain | ||||

| First-line therapy | ||||

| Antiseizure drugs | Gabapentin | Voltage-dependent calcium channels subunit alpha-2-delta-1 and delta-2 presynaptically located throughout the brain inhibitor, modulating the release of excitatory neurotransmitters which participate in epileptogenesis and nociception | PO: 100–1200 mg | Onset: ND Peak: 2–4 h Duration: ND |

| Pregabalin | Voltage-dependent calcium channel subunit alpha-2/delta-1, effect not known, inhibiting excitatory neurotransmitter release including glutamate, norepinephrine, serotonin, dopamine, substance P, and calcitonin gene-related peptide | PO: 75–300 mg BID | Onset: pain management efficacy may be noted as early as the first week of therapy. Peak: 1.5–3 h Duration: ND | |

| Antidepressants | ||||

| SNRI | Duloxetine | Serotonin and norepinephrine reuptake and dopamine reuptake inhibitor | PO: 30 mg daily for 7 days, then 60 mg daily for chemotherapy-induced peripheral neuropathy, 60 mg daily up to 120 for diabetes mellitus induced neuropathic pain | Onset: ND Peak: ND Duration: ND |

| Venlafaxine | Serotonin and norepinephrine reuptake inhibitor and weak dopamine reuptake inhibitor | PO: 15–100 mg | Onset: ND. Onset of action: pain management effects may be noted as early as the first week of therapy Peak: ND Duration: ND | |

| Tricyclic antidepressants | Amitriptyline | Inhibit norepinephrine and serotonin reuptake, block sodium and calcium channels and NMDA receptors | PO: Initial: 10 to 25 mg once daily at bedtime; may gradually increase dose based on response and tolerability in 10 to 25 mg increments at intervals ≥ 1 week up to 150 mg/day given once daily at bedtime or in 2 divided doses | Onset: ND Peak: 2–5 h Duration: ND |

| Second-line therapy | ||||

| Capsaicin 8% patch | Transient receptor potential vanilloid 1 receptor (TRPV1) agonist via a nociceptor defunctionalisation via a reduction in TRPV1 expression in nerve endings due to capsaicin stimulation | 0.025–0.1% transdermal patch | Onset: 2–4 weeks in continuous therapy Peak: ND Duration: ND | |

| Lidocaine patch | Nerve conduction blockage via a reduction in permeability to sodium ions | - | Onset: 4 h Peak: ND Duration: ND | |

| Tramadol | Mu-opiate receptor agonist, serotonin and norepinephrine reuptake inhibitor with inhibition of ascending pain pathways and altered perception and response to pain | PO 50–100 mg every 4–6 h, IV 50–100 mg every 4–6 h max dose 400 mg daily | Onset: < 1 h Peak: 2–3 h Duration: 6 h | |

| Third-line therapy | ||||

| See strong opioids | ||||

| Other drugs suggested as adjuvants for neuropathic and bone pain: | ||||

| Steroids | Dexamethasone, PO, IV | Adjuvant analgesic for inflammatory and anti-oedema effect | PO or IV: 0.3–0.6 mg/kg up to 10 mg | Onset: ND Peak: ND Duration: ND |

| Methylprednisolone, PO | Adjuvant analgesic for inflammatory and anti-oedema effect | PO: 16 mg | Onset: ND Peak: ND Duration: ND | |

| Prednisone, PO | Adjuvant analgesic for inflammatory and anti-oedema effect | PO: 40–60 mg | Onset: ND Peak: ND Duration: ND | |

| Magnesium Sulphate | NMDA receptor blocker | IV bolus of 1–3 g followed by an infusion of 10 g over 20 h | Onset: ND Peak: ND Duration: ND | |

| Bone pain: | ||||

| See NSAIDs, Steroids | ||||

| Visceral pain: | ||||

| See Steroids | ||||

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2023 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Serra, S.; Spampinato, M.D.; Riccardi, A.; Guarino, M.; Fabbri, A.; Orsi, L.; De Iaco, F. Pain Management at the End of Life in the Emergency Department: A Narrative Review of the Literature and a Practical Clinical Approach. J. Clin. Med. 2023, 12, 4357. https://doi.org/10.3390/jcm12134357

Serra S, Spampinato MD, Riccardi A, Guarino M, Fabbri A, Orsi L, De Iaco F. Pain Management at the End of Life in the Emergency Department: A Narrative Review of the Literature and a Practical Clinical Approach. Journal of Clinical Medicine. 2023; 12(13):4357. https://doi.org/10.3390/jcm12134357

Chicago/Turabian StyleSerra, Sossio, Michele Domenico Spampinato, Alessandro Riccardi, Mario Guarino, Andrea Fabbri, Luciano Orsi, and Fabio De Iaco. 2023. "Pain Management at the End of Life in the Emergency Department: A Narrative Review of the Literature and a Practical Clinical Approach" Journal of Clinical Medicine 12, no. 13: 4357. https://doi.org/10.3390/jcm12134357