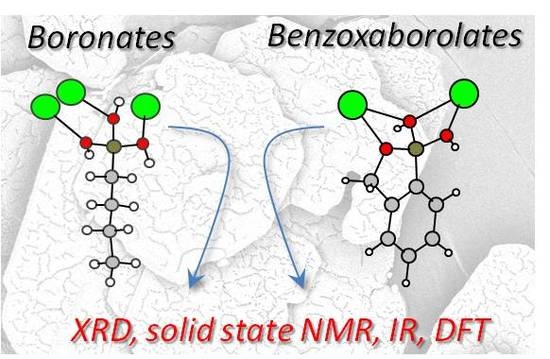

Coordination Networks Based on Boronate and Benzoxaborolate Ligands

Abstract

:1. Introduction

2. Crystal Structures Involving Simple Boronates and Benzoxaborolates

2.1. Acid-Base Properties of Boronic Acids and Benzoxaboroles

2.2. Boronate-Based Crystal Structures with Alkaline-Earth Metals

2.3. Benzoxaborolate-Based Crystal Structures with Alkaline-Earth Metals

3. Boronate and Benzoxaborolate Spectroscopic Signatures in Materials

3.1. Solid State NMR

3.2. Infrared Spectroscopy

4. Emerging Applications of Materials Involving Boronates and Benzoxaborolates

4.1. New Functional Coordination Polymers Based on Boronates

4.1.1. Boronates as a New Class of Ligands

4.1.2. Structures Based on Mixed Boronate/Carboxylate Ligands

4.2. Hybrid Materials Involving Benzoxaborolates: Towards New Ways of Formulating Benzoxaborole Drugs

5. Conclusions

Acknowledgments

Author Contributions

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Hall, D.G. Boronic Acids: Preparation and Applications in Organic Synthesis Medicine and Materials, 2nd ed.; Wiley-VCH: Weinheim, Germany, 2011. [Google Scholar]

- Zheng, H.; Hall, D.G. Boronic acid catalysis: An atom-economical platform for direct activation and functionalization of carboxylic acids and alcohols. Aldrichim. Acta 2014, 47, 41–51. [Google Scholar]

- Sun, X.; Zhai, W.; Fossey, J.S.; James, T.D. Boronic acids for fluorescence imaging of carbohydrates. Chem. Commun. 2016, 52, 3456–3469. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Green Version]

- Brooks, W.L.A.; Summerlin, B.S. Synthesis and applications of boronic acid-containing polymers: From materials to medicine. Chem. Rev. 2016, 116, 1375–1397. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kubo, Y.; Nishiyabu, R.; James, T.D. Hierarchical supramolecules and organization using boronic acid building blocks. Chem. Comm. 2015, 51, 2005–2020. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Smoum, R.; Rubinstein, A.; Dembitsky, V.M.; Srebnik, M. Boron containing compounds as protease inhibitors. Chem. Rev. 2012, 112, 4156–4220. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Adamczyk-Woźniak, A.; Borys, K.M.; Sporzyński, A. Recent developments in the chemistry and biological applications of benzoxaboroles. Chem. Rev. 2015, 115, 5224–5247. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Dowlut, M.; Hall, D.G. An improved class of sugar-binding boronic acids, soluble and capable of complexing glycosides in neutral water. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2006, 128, 4226–4227. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Anacor Pharmaceuticals. Available online: www.anacor.com (accessed on 28 April 2016).

- Clair, S.; Abel, M.; Porte, L. Growth of boronic acid based two-dimensional covalent networks on a metal surface under ultrahigh vacuum. Chem. Commun. 2014, 50, 9627–9635. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Li, D.; Chen, Y.; Liu, Z. Boronate affinity materials for separation and molecular recognition: Structure, properties and applications. Chem. Soc. Rev. 2015, 44, 8097–8123. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Cambre, J.N.; Sumerlin, B.S. Biomedical applications of boronic acid polymers. Polymer 2011, 52, 4631–4643. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, H.; Wang, H.; Liu, Y.; Liu, Z. A benzoboroxole-functionalized monolithic column for the selective enrichment and separation of cis-diol containing biomolecules. Chem. Commun. 2012, 48, 4115–4117. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zhao, Y.; Trewyn, B.G.; Slowing, I.I.; Lin, V.S.-Y. Mesoporous silica nanoparticle-based double drug delivery system for glucose-responsive controlled release of insulin and cyclic AMP. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2009, 131, 8398–8400. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ding, S.-Y.; Wang, W. Covalent organic frameworks (COFs): From design to applications. Chem. Soc. Rev. 2013, 42, 548–568. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lorand, J.P.; Edwards, J.O. Polyol complexes and structure of the benzeneboronate ion. J. Org. Chem. 1959, 24, 769–774. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cammidge, A.N.; Goddard, V.H.M.; Gopee, H.; Harrison, N.L.; Hughes, D.L.; Schubert, C.J.; Sutton, B.M.; Watts, G.L.; Whitehead, A.J. Aryl trihydroxyborates: Easily isolated discrete species convenient for direct application in coupling reactions. Org. Lett. 2006, 8, 4071–4074. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Babcock, L.; Pizer, R. Dynamics of boron acid complexation reactions. Formation of 1:1 boron acid-ligand complexes. Inorg Chem. 1980, 19, 56–61. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tomsho, J.W.; Pal, A.; Hall, D.G.; Benkovic, S.J. Ring structure and aromatic substituent effects on the pKa of the benzoxaborole pharmacophore. ACS Med. Chem Lett. 2012, 3, 48–52. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Haynes, W.M. Handbook of Chemistry and Physics, 92nd ed.; CEC Press: Boca Raton, FL, USA, 2011–2012. [Google Scholar]

- Popov, K.; Rönkkömäki, H.; Lajunen, L.H. Critical evaluation of the stability constants of phosphonic acids. Pure Appl. Chem. 2001, 73, 1641–1677. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Reinholdt, M.; Croissant, J.; Di Carlo, L.; Granier, D.; Gaveau, P.; Bégu, S.; Devoisselle, J.-M.; Mutin, H.; Smith, M.E.; Bonhomme, C.; et al. Synthesis and characterization of crystalline structures based on phenylboronate ligands bound to alkaline earth cations. Inorg. Chem. 2011, 50, 7802–7810. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sene, S.; Reinholdt, M.; Renaudin, G.; Berthomieu, D.; Zicovich-Wilson, C.M.; Gervais, C.; Gaveau, P.; Bonhomme, C.; Filinchuk, Y.; Smith, M.E.; et al. Boronate ligands in materials: Determining their local environment by using a combination of IR/solid-state NMR spectroscopies and DFT calculations. Chem. Eur. J. 2013, 19, 880–891. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Berthomieu, D.; Gervais, C.; Renaudin, G.; Reinholdt, M.; Sene, S.; Smith, M.E.; Bonhomme, C.; Laurencin, D. Coordination polymers based on alkylboronate ligands: Synthesis, characterization, and computational modeling. Eur. J. Inorg. Chem. 2015, 2015, 1182–1191. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Laurencin, D. Les acides boroniques et les boronates, des briques élémentaires pour la construction de matériaux. Actual. Chim. 2014, 391, 23–31. [Google Scholar]

- Wang, S.; Alekseev, E.V.; Miller, H.M.; Depmeier, W.; Albrecht-Schmitt, T.E. Boronic acid flux synthesis and crystal growth of uranium and neptunium boronates and borates: A low-temperature route to the first neptunium(V) borate. Inorg. Chem. 2010, 49, 9755–9757. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sene, S.; Bégu, S.; Gervais, C.; Renaudin, G.; Mesbah, A.; Smith, M.E.; Mutin, P.H.; van der Lee, A.; Nedelec, J.-M.; Bonhomme, C.; et al. Intercalation of benzoxaborolate anions in layered double hydroxides: Toward hybrid formulations for benzoxaborole drugs. Chem. Mater. 2015, 27, 1242–1254. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jaśkowska, E.; Justyniak, I.; Cyrański, M.K.; Adamczyk-Woźniak, A.; Sporzyński, A.; Zygadło-Monikowska, E.; Ziemkowska, W. Benzoxaborolate ligands in group 13 metal complexes. J. Organomet. Chem. 2013, 732, 8–14. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- MacKenzie, K.J.D.; Smith, M.E. Multinuclear Solid State NMR of Inorganic Materials; Pergamon Elsevier: Oxford, UK, 2002. [Google Scholar]

- Frydman, L.; Harwood, L.J.S. Isotropic spectra of half-integer quadrupolar spins from bidimensional magic-angle spinning NMR. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 1995, 117, 5367–5368. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sakellariou, D.; Lesage, A.; Hodgkinson, P.; Emsley, L. Homonuclear dipolar decoupling in solid-state NMR using continuous phase modulation. Chem. Phys. Lett. 2000, 319, 253–260. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ashbrook, S.E.; Smith, M.E. Solid state O-17 NMR—An introduction to the background principles and applications to inorganic materials. Chem. Soc. Rev. 2006, 35, 718–735. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Freitas, J.C.C.; Smith, M.E. Recent Advances in solid-state Mg-25 NMR spectroscopy. Ann. Rep. NMR Spectrosc. 2012, 75, 25–114. [Google Scholar]

- Laurencin, D.; Smith, M.E. Development of 43Ca solid state NMR spectroscopy as a probe of local structure in inorganic and molecular materials. Prog. Nucl. Magn. Reson. Spectrosc. 2013, 68, 1–40. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bonhomme, C.; Gervais, C.; Folliet, N.; Pourpoint, F.; Coelho Diogo, C.; Lao, J.; Jallot, E.; Lacroix, J.; Nedelec, J.-M.; Iuga, D.; et al. 87Sr solid-state NMR as a structurally sensitive tool for the investigation of materials: Antiosteoporotic pharmaceuticals and bioactive glasses. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2012, 134, 12611–12628. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Guerrero, G.; Alauzun, J.G.; Granier, M.; Laurencin, D.; Mutin, P.H. Phosphonate coupling molecules for the control of surface/interface properties and the synthesis of nanomaterials. Dalton Trans. 2013, 42, 12569–12585. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sene, S.; Bouchevreau, B.; Martineau, C.; Gervais, C.; Bonhomme, C.; Gaveau, P.; Mauri, F.; Bégu, S.; Mutin, P.H.; Smith, M.E.; et al. Structural study of calcium phosphonates: A combined synchrotron powder diffraction, solid-state NMR and first-principle calculations approach. CrystEngComm 2013, 15, 8763–8775. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fan, X.; Freslon, S.; Daiguebonne, C.; Le Pollès, L.; Calvez, G.; Bernot, K.; Yi, X.; Huang, G.; Guillou, O.A. Family of lanthanide-based coordination polymers with boronic acid as ligand. Inorg. Chem. 2015, 54, 5534–5546. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Couvreur, P. Nanoparticles in drug delivery: Past, present and future. Adv. Drug Deliv. Rev. 2013, 65, 21–23. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Argyo, C.; Weiss, V.; Bräuchle, C.; Bein, T. Multifunctional mesoporous silica nanoparticles as a universal platform for drug delivery. Chem. Mater. 2014, 26, 435–451. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, K.; Xu, Z.P.; Lu, J.; Tang, Z.Y.; Zhao, H.J.; Good, D.A.; Wei, M.Q. Potential for layered double hydroxides-based, innovative drug delivery systems. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2014, 15, 7409–7428. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sene, S.; McLane, J.; Schaub, N.; Bégu, S.; Mutin, P.H.; Ligon, L.; Gilbert, R.; Laurencin, D. Formulation of benzoxaborole drugs in PLLA: From materials preparation to in vitro release kinetics and cellular assays. J. Mater. Chem. B 2016, 4, 257–272. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Spokoyny, A.M.; Kim, D.; Sumrein, A.; Mirkin, C.A. Infinite coordination polymer nano- and microparticle structures. Chem. Soc. Rev. 2009, 38, 1218–1227. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lin, W.; Rieter, W.J.; Taylor, K.M.L. Modular synthesis of functional nanoscale coordination polymers. Angew. Chem. Int. Ed. 2009, 48, 650–658. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

| Acid-Base Couple | pKa | Reference |

|---|---|---|

| C6H5-B(OH)2/C6H5-B(OH)3− | ~8.9 | [1] |

| CH3-B(OH)2/CH3-B(OH)3− | 10.4 | [18] |

| C7H6BO(OH)/C7H6BO(OH)2− 1 | ~7.3 | [19] |

| CH3COOH/CH3COO− | 4.8 | [20] |

| CH3-PO(OH)2/CH3-PO2(OH)− | 2.2 | [21] |

| CH3-PO2(OH)−/CH3-PO32− | 7.5 | [21] |

© 2016 by the authors; licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC-BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Sene, S.; Pizzoccaro, M.A.; Vezzani, J.; Reinholdt, M.; Gaveau, P.; Berthomieu, D.; Bégu, S.; Gervais, C.; Bonhomme, C.; Renaudin, G.; et al. Coordination Networks Based on Boronate and Benzoxaborolate Ligands. Crystals 2016, 6, 48. https://doi.org/10.3390/cryst6050048

Sene S, Pizzoccaro MA, Vezzani J, Reinholdt M, Gaveau P, Berthomieu D, Bégu S, Gervais C, Bonhomme C, Renaudin G, et al. Coordination Networks Based on Boronate and Benzoxaborolate Ligands. Crystals. 2016; 6(5):48. https://doi.org/10.3390/cryst6050048

Chicago/Turabian StyleSene, Saad, Marie Alix Pizzoccaro, Joris Vezzani, Marc Reinholdt, Philippe Gaveau, Dorothée Berthomieu, Sylvie Bégu, Christel Gervais, Christian Bonhomme, Guillaume Renaudin, and et al. 2016. "Coordination Networks Based on Boronate and Benzoxaborolate Ligands" Crystals 6, no. 5: 48. https://doi.org/10.3390/cryst6050048