Food Parenting Practices Promoted by Childcare and Primary Healthcare Centers in Chile: What Influences Do These Practices Have on Parents? A Qualitative Study

Abstract

:1. Introduction

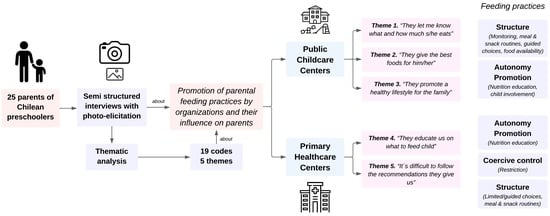

2. Method

2.1. Research Team Reflexivity

2.2. Study Design

2.2.1. Participant Selection

2.2.2. Setting

2.2.3. Data Collection

2.3. Data Analysis

3. Findings

3.1. Public Childcare Centers

3.2. Primary Healthcare Center

4. Discussion

Implication for Practice, Policy, and Future Research

5. Conclusions

Supplementary Materials

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

References

- FAO; IFAD; UNICEF; WHO. The State of Food Security and Nutrition in the World 2022. Repurposing Food and Agricultural Policies to Make Healthy Diets More Affordable; FAO: Rome, Italy, 2022. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ministerio de Salud. Norma Técnica Para La Supervisión de Salud Integral de Niños y Niñas de 0 a 9 Años En La Atención Primaria de Salud—2a Edición, Actualización 2021. Capítulo 2. Componentes Transversales y Específicos de La Supervisión de Salud Integral Infantil; Ministerio de Salud: Santiago, Chile, 2021. Available online: https://www.minsal.cl/wp-content/uploads/2021/12/Capítulo-2-Web.pdf (accessed on 22 November 2023).

- Ministerio de Salud. Vigilancia Del Estado Nutricional de La Población Bajo Control y de La Lactancia Materna En El Sistema Público de Salud de Chile; Ministerio de Salud: Santiago, Chile, 2020. Available online: http://www.bibliotecaminsal.cl/wp/wp-content/uploads/2019/11/Informe-Vigilancia-Nutricional-2017.pdf (accessed on 22 November 2023).

- Vio del Río, F. Obesidad Infantil. Una Pandemia Invisible. Llamado Urgente a La Acción, 1st ed.; Permanyer: Mexico City, Mexico, 2023. [Google Scholar]

- Junta Nacional de Auxilio Escolar y Becas. Informe Mapa Nutricional 2022. 2023. Available online: https://www.junaeb.cl/wp-content/uploads/2023/07/INFORME-EJECUTIVO_2022_VF.pdf (accessed on 29 October 2023).

- Araya, C.; Corvalán, C.; Cediel, G.; Taillie, L.S.; Reyes, M. Ultra-Processed Food Consumption Among Chilean Preschoolers Is Associated with Diets Promoting Non-communicable Diseases. Front. Nutr. 2021, 8, 601526. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- United Nations Children’s Fund (UNICEF). Case Study. Santiago, Chile. Panamá, 2022. Available online: https://www.unicef.org/lac/media/36916/file/Case%20study:%20Chile.pdf (accessed on 29 October 2023).

- Pinheiro, A.C.; Quintiliano-Scarpelli, D.; Flores, J.A.; Álvarez, C.; Suárez-Reyes, M.; Palacios, J.L.; Quevedo, T.P.; de Oliveira, M.R.M. Food Availability in Different Food Environments Surrounding Schools in a Vulnerable Urban Area of Santiago, Chile: Exploring Socioeconomic Determinants. Foods 2022, 11, 901. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- United Nations Children’s Fund UNICEF; World Health Organization; World Bank Group Joint Child Malnutrition Estimates. Levels and Trends in Child Malnutrition: Key Findings of the 2020 Edition of the Joint Child Malnutrition Estimates; WHO: Geneva, Switzerland, 2020; Available online: https://www.unicef.org/sites/default/files/2020-06/Joint-malnutrition-estimates-2020.pdf (accessed on 22 November 2023).

- Birch, L.L.; Ventura, A.K. Preventing childhood obesity: What works? Int. J. Obes. 2009, 33, S74–S81. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Story, M.; Kaphingst, K.M.; Robinson-O’Brien, R.; Glanz, K. Creating Healthy Food and Eating Environments: Policy and Environmental Approaches. Annu. Rev. Public Health 2008, 29, 253–272. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Masento, N.A.; Dulay, K.M.; Harvey, K.; Bulgarelli, D.; Caputi, M.; Cerrato, G.; Molina, P.; Wojtkowska, K.; Pruszczak, D.; Barlińska, J.; et al. Parent, child, and environmental predictors of vegetable consumption in Italian, Polish, and British preschoolers. Front. Nutr. 2022, 9, 958245. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ningning, W.; Wenguang, C. Influence of family parenting style on the formation of eating behaviors and habits in preschool children: The mediating role of quality of life and nutritional knowledge. PLoS ONE 2023, 18, e0288878. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Vaughn, A.E.; Ward, D.S.; Fisher, J.O.; Faith, M.S.; Hughes, S.O.; Kremers, S.P.; Musher-Eizenman, D.R.; O’connor, T.M.; Patrick, H.; Power, T.G. Fundamental constructs in food parenting practices: A content map to guide future research. Nutr. Rev. 2015, 74, 98–117. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Engle, P.L.; Pelto, G.H. Responsive Feeding: Implications for Policy and Program Implementation. J. Nutr. 2011, 141, 508–511. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Balantekin, K.N.; Anzman-Frasca, S.; Francis, L.A.; Ventura, A.K.; Fisher, J.O.; Johnson, S.L. Positive parenting approaches and their association with child eating and weight: A narrative review from infancy to adolescence. Pediatr. Obes. 2020, 15, e12722. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Say, A.; Garcia, X.d.l.P.; Mallan, K.M. The correlation between different operationalisations of parental restrictive feeding practices and children’s eating behaviours: Systematic review and meta-analyses. Appetite 2023, 180, 106320. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shloim, N.; Edelson, L.R.; Martin, N.; Hetherington, M.M. Parenting Styles, Feeding Styles, Feeding Practices, and Weight Status in 4–12 Year-Old Children: A Systematic Review of the Literature. Front. Psychol. 2015, 6, 1849. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ventura, A.K.; Birch, L.L. International Journal of Behavioral Nutrition and Physical Activity Does Parenting Affect Children’s Eating and Weight Status? J. Behav. Nutr. Phys. Act. 2008, 5, 15. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pérez-Escamilla, R.; Jimenez, E.Y.; Dewey, K.G. Responsive Feeding Recommendations: Harmonizing Integration into Dietary Guidelines for Infants and Young Children. Curr. Dev. Nutr. 2021, 5, nzab076. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ayala, G.X.; Monge-Rojas, R.; King, A.C.; Hunter, R.; Berge, J.M. The Social Environment and Childhood Obesity: Implications for Research and Practice in the United States and Countries in Latin America. Obes. Rev. 2021, 22, e13246. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Britto, P.R.; Lye, S.J.; Proulx, K.; Yousafzai, A.K.; Matthews, S.G.; Vaivada, T.; Perez-Escamilla, R.; Rao, N.; Ip, P.; Fernald, L.C.H.; et al. Nurturing care: Promoting early childhood development. Lancet 2016, 389, 91–102. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Subsecretaría de Educación Parvularia. Informe de Caracterización de La Educación Parvularia. Oficial. 2019. Available online: https://bibliotecadigital.mineduc.cl/bitstream/handle/20.500.12365/14480/Inf-Gral-EdParv-cierre.pdf?sequence=1&isAllowed=y (accessed on 22 November 2023).

- Fundación Integra Ministerio de Educación. Reporte Integra 2022. Santiago, 2022. Available online: https://www.integra.cl/wp-content/uploads/2023/05/reporte_integra_2022.pdf (accessed on 7 November 2023).

- Berk, L.E.; Meyers, A.B. Theory and Research in Child Development; Pearson: Boston, MA, USA, 2015; pp. 3–7. [Google Scholar]

- Junta Nacional de Jardines Infantiles. Plan Estratégico JUNJI 2019–2023. Actualización 2020. Santiago, Chile, 2020. Available online: https://www.junji.gob.cl/wp-content/uploads/2020/08/PLAN_ESTRATEGICO_JUNJI_2020-1.pdf (accessed on 29 October 2023).

- Red de Salas Cunas y Jardines Infantiles. INTEGRA. Política de Calidad Educativa. 2017. Available online: https://www.integra.cl/wp-content/uploads/2018/03/POLITICA-DE-CALIDAD-EDUCATIVA-2017-2.pdf (accessed on 29 October 2023).

- Vine, M.; Hargreaves, M.B.; Briefel, R.R.; Orfield, C. Expanding the Role of Primary Care in the Prevention and Treatment of Childhood Obesity: A Review of Clinic- and Community-Based Recommendations and Interventions. J. Obes. 2013, 2013, 172035. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- World Health Organization. A Primary Health Care Approach to Obesity Prevention and Management in Children and Adolescents: Policy Brief. 2023. Available online: https://www.sochob.cl/web1/wp-content/uploads/2023/05/A-primary-health-care-approach-to-obesity-prevention-and-management-in-children-and-adolescents-policy-brief.pdf (accessed on 29 October 2023).

- Turer, C.B.; Mehta, M.; Durante, R.; Wazni, F.; Flores, G. Parental perspectives regarding primary-care weight-management strategies for school-age children. Matern. Child Nutr. 2014, 12, 326–338. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kain, J.; Uauy, R.; Concha, F.; Leyton, B.; Bustos, N.; Salazar, G.; Lobos, L.; Vio, F. School-Based Obesity Prevention Interventions for Chilean Children During the Past Decades: Lessons Learned. Adv. Nutr. Int. Rev. J. 2012, 3, 616S–621S. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Santos, J.L.; Kain, J.; Dominguez-Vásquez, P.; Lera, L.; Galván, M.; Corvalán, C.; Uauy, R. Maternal anthropometry and feeding behavior toward preschool children: Association with childhood body mass index in an observational study of Chilean families. Int. J. Behav. Nutr. Phys. Act. 2009, 6, 93. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rana, K.; Poudel, P.; Chimoriya, R. Qualitative Methodology in Translational Health Research: Current Practices and Future Directions. Healthcare 2023, 11, 2665. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Creswell, J.W. Preliminary Considerations. In Research Design Qualitative, Quantitative and Mixed Methods Approaches; Knight, V., Ed.; SAGE Publications: Thousand Oaks, CA, USA, 2014. [Google Scholar]

- Kaushik, V.; Walsh, C.A. Pragmatism as a Research Paradigm and Its Implications for Social Work Research. Soc. Sci. 2019, 8, 255. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- OECD. OECD Economic Surveys: Chile, 2015. Available online: https://www.oecd-ilibrary.org/oecd-economic-surveys-chile-2015_5jrqm0ppdsg6.pdf?itemId=%2Fcontent%2Fpublication%2Feco_surveys-chl-2015-en&mimeType=pdf (accessed on 22 November 2023).

- Ministerio de Desarrollo Social y Familia. Gobierno de Chile. Evolución de La Pobreza 1990–2017: ¿Cómo Ha Cambiado Chile? 2020. Available online: http://observatorio.ministeriodesarrollosocial.gob.cl/storage/docs/pobreza/InformeMDSF_Gobcl_Pobreza.pdf (accessed on 22 November 2023).

- Lorenz, L.S.; Kolb, B. Involving the public through participatory visual research methods. Health Expect. 2009, 12, 262–274. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Patricia, G.E.; Vizcarra, M.; Palomino, A.M.; Valencia, A.; Iglesias, L.; Schwingel, A. The photo-elicitation of food worlds: A study on the eating behaviors of low socioeconomic Chilean women. Appetite 2017, 111, 96–104. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Chakona, G.; Shackleton, C. Food Taboos and Cultural Beliefs Influence Food Choice and Dietary Preferences among Pregnant Women in the Eastern Cape, South Africa. Nutrients 2019, 11, 2668. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- de Garine, I. Views about food prejudice and stereotypes. Soc. Sci. Inf. 2001, 40, 487–507. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Johnson, C.M.; Sharkey, J.R.; Dean, W.R.; McIntosh, W.A.; Kubena, K.S. It’s who I am and what we eat. Mothers’ food-related identities in family food choice. Appetite 2011, 57, 220–228. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Johnson, C.M.; Sharkey, J.R.; Dean, W.R. It’s all about the children: A participant-driven photo-elicitation study of Mexican-origin mothers’ food choices. BMC Women’s Health 2011, 11, 41. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Espinoza, P.G.; Vizcarra, M.; Molina, P.; Coloma, M.J.; Stecher, M.J.; Bost, K.; Schwingel, A. Exploring parents’ perspectives on feeding their young children: A qualitative study using photo-elicitation in Chile. Public Health Nutr. 2022, 25, 2415–2425. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Braun, V.; Clarke, V. Using thematic analysis in psychology. Qual. Res. Psychol. 2006, 3, 77–101. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kaiser, K. Protecting Respondent Confidentiality in Qualitative Research. Qual. Health Res. 2009, 19, 1632–1641. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Carter, N.; Bryant-Lukosius, D.; DiCenso, A.; Blythe, J.; Neville, A.J. The Use of Triangulation in Qualitative Research. Oncol. Nurs. Forum 2014, 41, 545–547. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lindsay, A.C.; Machado, M.T.; Sussner, K.M.; Hardwick, C.K.; Peterson, K.E. Infant-Feeding Practices and Beliefs about Complementary Feeding among Low-Income Brazilian Mothers: A Qualitative Study. Food Nutr. Bull. 2008, 29, 15–24. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Johnson, S.L.; Ramsay, S.; Shultz, J.A.; Branen, L.J.; Fletcher, J.W. Creating Potential for Common Ground and Communication Between Early Childhood Program Staff and Parents About Young Children’s Eating. J. Nutr. Educ. Behav. 2013, 45, 558–570. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Mena, N.Z.; Risica, P.M.; Gans, K.M.; Lofgren, I.E.; Gorman, K.; Tobar, F.K.; Tovar, A. Communication With Family Child Care Providers and Feeding Preschool-Aged Children: Parental Perspectives. J. Nutr. Educ. Behav. 2020, 52, 10–20. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lindsay, A.C.; Greaney, M.L.; Wallington, S.F.; Sands, F.D.; Wright, J.A.; Salkeld, J. Latino parents’ perceptions of the eating and physical activity experiences of their pre-school children at home and at family child-care homes: A qualitative study. Public Health Nutr. 2016, 20, 346–356. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Cooke, L. The importance of exposure for healthy eating in childhood: A review. J. Hum. Nutr. Diet. 2007, 20, 294–301. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Dwyer, J.; Needham, L.; Simpson, J.R.; Heeney, E.S. Parents report intrapersonal, interpersonal, and environmental barriers to supporting healthy eating and physical activity among their preschoolers. Appl. Physiol. Nutr. Metab. 2008, 33, 338–346. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ministerio de Desarrollo Social. Informe de Descripción de Programas Sociales. Programa de Alimentación Escolar. 2016; p. 7. Available online: https://programassociales.ministeriodesarrollosocial.gob.cl/pdf/2017/PRG2017_3_60159_2.pdf (accessed on 22 November 2023).

- Blom-Hoffman, J.; Kelleher, C.; Power, T.J.; Leff, S.S. Promoting healthy food consumption among young children: Evaluation of a multi-component nutrition education program. J. Sch. Psychol. 2004, 42, 45–60. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hawkes, C. Promoting Healthy Diets Through Nutrition Education and Changes in the Food Environment: An International Review of Actions and Their Effectiveness. 2013. Available online: https://www.fao.org/3/i3235e/i3235e.pdf (accessed on 22 November 2023).

- Suwalska, J.; Bogdański, P. Social Modeling and Eating Behavior—A Narrative Review. Nutrients 2021, 13, 1209. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dev, D.A.; McBride, B.A.; Speirs, K.E.; Donovan, S.M.; Cho, H.K. Predictors of Head Start and Child-Care Providers’ Healthful and Controlling Feeding Practices with Children Aged 2 to 5 Years. J. Acad. Nutr. Diet. 2014, 114, 1396–1403. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pérez-Escamilla, R.; Segura-Pérez, S.; Lott, M. Feeding Guidelines for Infants and Young Toddlers: A Responsive Parenting Approach. Nutr. Today 2017, 52, 223–231. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Andreyeva, T.; Kenney, E.L.; O’Connell, M.; Sun, X.; Henderson, K.E. Predictors of Nutrition Quality in Early Child Education Settings in Connecticut. J. Nutr. Educ. Behav. 2018, 50, 458–467. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Matwiejczyk, L.; Mehta, K.; Scott, J.; Tonkin, E.; Coveney, J. Characteristics of Effective Interventions Promoting Healthy Eating for Pre-Schoolers in Childcare Settings: An Umbrella Review. Nutrients 2018, 10, 293. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ministerio de Educación. JUNJI. Educación Parvularia. Available online: https://www.junji.gob.cl/programas-educativos/ (accessed on 22 November 2023).

- Junta Nacional de Jardines Infantiles JUNJI. Estrategias Para Afianzar La Articulación y Comunicación Con Las Familias. 2021. Available online: https://www.junji.gob.cl/wp-content/uploads/2021/01/Estrategia-Comunicacion-Familias-21.01.21.pdf (accessed on 22 November 2023).

- Hughes, S.O.; Patrick, H.; Power, T.G.; Fisher, J.O.; Anderson, C.B.; Nicklas, T.A. The Impact of Child Care Providers’ Feeding on Children’s Food Consumption. J. Dev. Behav. Pediatr. 2007, 28, 100–107. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mary, P.D.S.; Kaphingst, K.M.; French, S. The Role of Child Care Settings in Obesity Prevention. Futur. Child. 2006, 16, 143–168. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- MINSAL. Política Nacional De Alimentación Y Nutrición; MINSAL: Santiago, Chile, 2017. [Google Scholar]

- Arora, A.; Rana, K.; Manohar, N.; Li, L.; Bhole, S.; Chimoriya, R. Perceptions and Practices of Oral Health Care Professionals in Preventing and Managing Childhood Obesity. Nutrients 2022, 14, 1809. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Cheng, H.; George, C.; Dunham, M.; Whitehead, L.; Denney-Wilson, E. Nurse-led interventions in the prevention and treatment of overweight and obesity in infants, children and adolescents: A scoping review. Int. J. Nurs. Stud. 2021, 121, 104008. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ray, D.; Sniehotta, F.; McColl, E.; Ells, L. Barriers and facilitators to implementing practices for prevention of childhood obesity in primary care: A mixed methods systematic review. Obes. Rev. 2022, 23, e13417. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Centro de Políticas Públicas UC. Serie No. 67: Fortalecimiento de La Atención Primaria de Salud: Propuestas Para Mejorar El Sistema Sanitario Chileno; Centro de Políticas Públicas UC: Santiago, Chile, 2014; Volume 9, p. 19. [Google Scholar]

- Jansen, E.; Mulkens, S.; Emond, Y.; Jansen, A. From the Garden of Eden to the land of plenty: Restriction of fruit and sweets intake leads to increased fruit and sweets consumption in children. Appetite 2008, 51, 570–575. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Harte, S.; Theobald, M.; Trost, S.G. Culture and community: Observation of mealtime enactment in early childhood education and care settings. Int. J. Behav. Nutr. Phys. Act. 2019, 16, 69. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ministerio de Salud de Chile. Subsecretaría de Redes Asistenciales. División Atención Primaria. Orientaciones Para La Imple-Mentación Del Modelo de Atención Integral de Salud Familiar y Comunitaria: Dirigido a Equipos de Salud; Ministerio de Salud de Chile (MINSAL): Santiago, Chile, 2013.

- Resnicow, K.; Davis, R.; Rollnick, S. Motivational Interviewing for Pediatric Obesity: Conceptual Issues and Evidence Review. J. Am. Diet. Assoc. 2006, 106, 2024–2033. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Brown, C.L.; Perrin, E.M. Obesity Prevention and Treatment in Primary Care. Acad. Pediatr. 2018, 18, 736–745. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Austin, Z.; Sutton, J. Qualitative Research: Getting Started. Can. J. Hosp. Pharm. 2014, 67, 436–440. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Fujimoto, G.; Peralta, V. La Atención Integral de la Primera Infancia en América Latina: Ejes Centrales Y Los Desafíos Para El Siglo XXI. Available online: https://www.oas.org/udse/readytolearn/documentos/7.pdf (accessed on 6 November 2023).

- Corvalán, C.; Garmendia, M.L.; Jones-Smith, J.; Lutter, C.K.; Miranda, J.J.; Pedraza, L.S.; Popkin, B.M.; Ramirez-Zea, M.; Salvo, D.; Stein, A.D. Nutrition status of children in Latin America. Obes. Rev. 2017, 18, 7–18. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cuba-Fuentes, M.S.; Romero-Albino, Z.; Dominguez, R.; Mezarina, L.R.; Villanueva, R. Dimensiones claves para fortalecer la atención primaria en el Perú a cuarenta años de Alma Ata. An. Fac. Med. 2018, 79, 346–350. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hughes, S.O.; Power, T.G.; Fisher, J.O.; Mueller, S.; Nicklas, T.A. Revisiting a neglected construct: Parenting styles in a child-feeding context. Appetite 2005, 44, 83–92. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Characteristics | Total Participants n = 25 |

|---|---|

| Average age and age range (years) | 32.1 (21–49) |

| Education level, n (%) | |

| Elementary | 3 (12) |

| High school | 13 (52) |

| Vocational | 3 (12) |

| Higher education | 6 (24) |

| Work status, n (%) | |

| Unemployed | 5 (20) |

| Currently working n (%) | 20 (80) |

| Housing | |

| Own a house | 10 (40) |

| Rent a house | 5 (20) |

| Live with other family members | 10 (40) |

| Household size (range) | 2–14 |

| Type of caregiver, n (%) | |

| Mother | 24 (96) |

| Father | 1 (4) |

| Family type n (%) | |

| Two-parent family | 20 (80) |

| One-parent family | 6 (24) |

| Type of health insurance n (%) | |

| Public | 18 (72%) |

| Private | 2 (8%) |

| Both | 5 (20%) |

| Category of Food Parenting Practices | Childcare Center | Primary Healthcare Center |

|---|---|---|

| Structure | Monitoring (n = 19) | Limited/guided choices (n = 17) |

| Teachers/teacher aides give information about child eating behaviors (how much, what foods the child ate or did not eat) or parents ask about child eating behaviors. | Healthcare providers promote the reduction in portion sizes. | |

| Parents can assess whether they should give more food or can understand why their child eats more or less at home. | Recommend healthier food brands and replace foods for the child with other healthier options. | |

| Meal and snack routines (n = 16) | Meal and snack routines (n = 10) | |

| Childcare centers have a schedule for providing meals and snacks. Components of lunch are salad, main course, and dessert. Parents try to keep the meal routines at home (schedule and food order at lunch) but more flexibly. Childcare gives their meal plan weekly to families. Parents can go to the childcare center to feed their children or help teachers to feed the children during mealtimes. | Healthcare providers promote meal/snack routines through the delivery of a meal plan or feeding guidelines that include schedules, meal times, and amounts of food for the child. | |

| Limited/Guided choices (n = 9) | ||

| In the childcare center, healthy food is offered, but teachers and teacher aides ask parents about food preferences, allergies, etc. | ||

| Food availability (n = 9) | ||

| Childcare centers provide meals with adequate energy. Foods are diverse because they offer fruits, vegetables, legumes, etc. Children are not allowed to bring food categorized as less healthy (high in calories, sodium, and saturated fats, among others, according to nutritional warning labels on food and drink products). | ||

| Autonomy support or promotion | Nutrition education (n = 10) | Nutrition education (n = 16) |

| Parents: Childcare centers promote a healthy lifestyle by offering workshops about foods, healthy eating, and obesity. | Healthcare providers educate parents about the benefits of healthy eating, child weight, growth status, and the consequences of excess weight. | |

| Children: Childcare centers educate children about nutritional warning labels on food and drink products, a healthy weight, and the relationship between sugary food and cavities. | ||

| Child involvement (n = 5) | ||

| Teachers/teacher aides prepare mixed fruits and other foods with children. They also encourage children to eat by themselves. | ||

| Depending on the theme of the week, teachers/teacher aides provide opportunities for children to taste varied food and preparations, including fruits, legumes, vegetables, fish, etc. | ||

| Coercive control | Restriction (n = 2) | Restriction (n = 9) |

| Childcare centers suggest avoiding the consumption of unhealthy foods (e.g., with nutritional warning labels on food and drinks). | Parents indicate that a strong and frequent suggestion from healthcare providers is food restriction (type or quantity) of a diverse food such as unhealthy foods. |

| Themes | Key Quotes and Parental Practice They Promote | |

|---|---|---|

| Public Childcare Centers | ||

| Theme 1. “They let me know what and how much s/he eats” | Monitoring (structure): “The childcare center does not force any child to eat, but it does let parents know about it when they pick them up, “you know, [the child] did not eat,” so they give the children something else at home... and the teachers here also say “the child has not eaten anything”, so I know I have to have something for my child back home” (E16) | Monitoring (structure): “I ask [the teachers or teacher aides at the childcare center], “Did the child eat?”, and they say “No, they ate this food, and we gave them more milk… they ate half a bread bun more.” We still get home to reinforce food…every day we need to ask the childcare center teachers… they always informed me, every day they told me if the child had had milk, if they’d had lunch, without me asking. “Do not worry, today he ate 100%,” which means the child has eaten all the food…” (E24) |

| Theme 2. “They give the best foods for him/her” | Meal and snack routines (structure): “[Related to the mother learning about the child’s feeding thanks to the childcare center… it was about eliminating some foods not needed, I mean, maybe add dessert or something like that [like in the childcare center], because before I gave the child the meal and a juice, but here they are used to giving them the dessert and the salad, so then I started adding [to foods at home] dessert and salad. It could be a smaller portion, but as I had more things, I became used to it” (E11) | Food availability (structure): “I know that in the childcare center they just give them healthy foods, so I am not afraid that my child goes to the childcare center and eats because I know that they give them only good foods. They give them legumes, the same things I make here [at home]. They give them “carbonada” [a Chilean vegetable and beef soup] they give them better meat than I do…” (E6) |

| Theme 2. “They give the best foods for him/her” | Meal and snack routines (structure): [Related to how the childcare center has influenced the child’s feeding at home] “... In the schedules... The child came in (to the childcare center) drinking from a baby bottle milk... Later “No, mom, I don’t bring the bottle”, because the child already drinks from a cup”... because almost all the children were already drinking from a cup and he wasn’t. And the other thing is that I don’t know, he [child] is one of those people who imitates everything in that aspect [of eating]... The schedule and the types of food, they do not add salt or anything... besides, they [the educators] are always asking in the childcare center if he is allergic to something [food], what he cannot eat, they always ask you to know what [food] to give him and what not to give him” (E2). | |

| Theme 3. “They promote a healthy lifestyle for the whole family” | Child involvement (autonomy support or promotion): “In this childcare center they do help a lot…, the projects they have done here, they have done one of healthy lifestyle, last year they had physical education teachers, they had zumba lessons for mums... Now these days they ask for fruit every day in the classroom because I think that during recess when children are very restless, they tell them “ok, go get a fruit”… Sometimes, any day of the week they do healthy activities, say, making an “alfajor” but a healthy one, or I don’t know, a fruit salad, that the children themselves make, so [the child] likes that” (E21) | Nutrition education (autonomy support or promotion): “In the childcare center [the child learnt about front-of-package food warning labels]... There was a workshop and they did, like, activities about the labels. I mean, “don’t give me this mum because it has too many labels” [says the preschooler]... that it had too much sugar…fats, that sort of thing. The children start to, like, notice… avoid the black stuff [foods with food warning labels]” (E14) |

| Healthcare Center | ||

| Theme 4. “They educate us on what to feed our child” | Nutrition education (autonomy support or promotion): “The nutritionist [from the healthcare center] in that sense [how to approach feeding] was very clear and she would tell me all the steps to follow, or how to do it. I told [the child] “Look, your mum is going to tell me about you… if I tell you to eat half a bread bun, it has to be half, and if not, eat a fruit.” So then they would explain everything to both, me and the child... ” (E15) | Limited/guided choices (structure): “The pediatrician told us that we already had to start giving some foods [offer foods to the child]. I can’t remember if there was a list of foods, yes, I think so, she gave me a list, a guide... she gave me a list of the foods I had to incorporate in the daily diet of the child, um... carbohydrate from potato, pasta or rice plus a protein, which was mostly chicken, and then to start with a certain amount of vegetables... and that’s how we start. (E14) |

| Theme 5. “It is difficult to follow the recommendations they give us” | Restriction (coercive control): “… I have nothing to say, they have explained me well [in the public healthcare center about the preschooler’s feeding]. The problem is that sometimes, how do you do it? Because I say, “ok, if they give the child milk at 4 and at 7 because they should eat every three hours, she [the nutritionist] says to give him a little amount, I mean, one tries, really, but I told her: he [the child] really likes eating fruit. She [the nutritionist] said, “... fruit is healthy but in big amounts it is also harmful,” so, then what do I give him?” (E15) | Restriction (coercive control): “I tell the nutritionist [at the healthcare center] yes, yes, but then, I still give [the child] some foods, because then what is wrong with yogurt, jelly? As I am saying, for her everything is bad, [the child] couldn’t eat sausage, egg, or there were too many lentils... they tell me to make him gain weight, but I can’t give him everything and then if he gains weight, they are going to tell me that he should lose weight, so then it’s like, I’m done... I am not going to rack my brain... I know how he [the preschooler] is, I know what he is going to eat, and if I forbid him to eat something he is going to want to eat it even more... As I am saying, [the child] can eat many things, but just a little bit of everything” (E7) |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2023 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Molina, P.; Coloma, M.J.; Gálvez, P.; Stecher, M.J.; Vizcarra, M.; Schwingel, A. Food Parenting Practices Promoted by Childcare and Primary Healthcare Centers in Chile: What Influences Do These Practices Have on Parents? A Qualitative Study. Children 2023, 10, 1875. https://doi.org/10.3390/children10121875

Molina P, Coloma MJ, Gálvez P, Stecher MJ, Vizcarra M, Schwingel A. Food Parenting Practices Promoted by Childcare and Primary Healthcare Centers in Chile: What Influences Do These Practices Have on Parents? A Qualitative Study. Children. 2023; 10(12):1875. https://doi.org/10.3390/children10121875

Chicago/Turabian StyleMolina, Paulina, María José Coloma, Patricia Gálvez, María José Stecher, Marcela Vizcarra, and Andiara Schwingel. 2023. "Food Parenting Practices Promoted by Childcare and Primary Healthcare Centers in Chile: What Influences Do These Practices Have on Parents? A Qualitative Study" Children 10, no. 12: 1875. https://doi.org/10.3390/children10121875