Regulation of Nitric Oxide Production in the Developmental Programming of Hypertension and Kidney Disease

Abstract

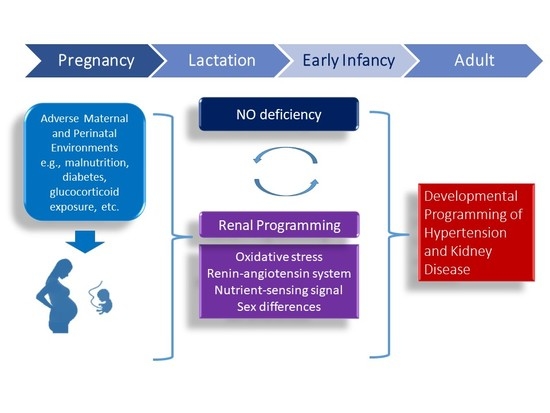

:1. Introduction

2. Regulation of Nitric Oxide in the Kidney

3. Developmental Programming of Hypertension and Kidney Disease: Insight Provided by Human Study

4. Mechanisms of Renal Programming Related to Nitric Oxide (NO) Pathway

4.1. Oxidatice Stress

4.2. Renin-Angiotensin System

4.3. Nutrient-Sensing Signals

4.4. Sex Differences

4.5. Others

5. Reprogramming Interventions Targeting the NO Pathway to Prevent the Programming of Hypertension and Kidney Disease

5.1. Substrate for Nitric Oxide Synthase (NOS)

5.2. Asymmetric Dimethylarginine (ADMA)-Lowering Agents

5.3. NO Donors

5.4. Others

6. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Conflicts of Interest

Abbreviations

| ADMA | Asymmetric dimethylarginine |

| AGXT2 | Alanine-glyoxylate aminotransferase 2 |

| AMPK | Adenosine monophosphate-activated protein kinase |

| CAKUT | Congenital anomaly of kidney and urinary tract |

| CAT | Cationic amino acid transporter |

| DDAH | Dimethylarginine dimethylaminohydrolase |

| DOHaD | Developmental origins of health and disease |

| FHH | Fawn hooded hypertensive rat |

| KEGG | Kyoto Encyclopedia of Genes and Genomes |

| L-NAME | NG-nitro-L-arginine-methyl ester |

| NCD | Non-communicable disease |

| NOS | Nitric oxide synthase |

| PGC-1α | Peroxisome proliferator-activated receptor-γ coactivator-1α |

| PPAR | Peroxisome proliferator-activated receptor |

| PIN | Protein inhibitor of neuronal nitric oxide synthase |

| PRMT | Protein arginine methyltransferase |

| RAS | Renin-angiotensin system |

| SDMA | Symmetric dimethylarginine |

| SHR | Spontaneously hypertensive rat |

| SIRT | Silent information regulator transcript |

| TCDD | 2,3,7,8-tetrachlorodibenzo-p-dioxin |

References

- Sladek, S.M.; Magness, R.R.; Conrad, K.P. Nitric oxide and pregnancy. Am. J. Physiol. Regul. Integr. Comp. Physiol. 1997, 272, R441–R463. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Khalil, A.; Hardman, L.; O’Brien, P. The role of arginine, homoarginine and nitric oxide in pregnancy. Amino Acids 2015, 47, 1715–1727. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Baylis, C.; Beinder, E.; Suto, T.; August, P. Recent insights into the roles of nitric oxide and renin-angiotensin in the pathophysiology of preeclamptic pregnancy. Semin. Nephrol. 1998, 18, 208–230. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Huang, L.T.; Hsieh, C.S.; Chang, K.A.; Tain, Y.L. Roles of Nitric Oxide and Asymmetric Dimethylarginine in Pregnancy and Fetal Programming. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2012, 13, 14606–14622. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Green Version]

- Hanson, M.; Gluckman, P. Developmental origins of noncommunicable disease: Population and public health implications. Am. J. Clin. Nutr. 2011, 94, 1754S–1758S. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zarocostas, J. Need to increase focus on non-communicable diseases in global health, says WHO. Br. Med. J. 2010, 341, c7065. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Barker, D.J.; Bagby, S.P.; Hanson, M.A. Mechanisms of disease: In utero programming in the pathogenesis of hypertension. Nat. Clin. Pract. Nephrol. 2006, 2, 700–707. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chong, E.; Yosypiv, I.V. Developmental programming of hypertension and kidney disease. Int. J. Nephrol. 2012, 2012, 760580. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Baylis, C. Nitric oxide synthase derangements and hypertension in kidney disease. Curr. Opin. Nephrol. Hypertens. 2012, 21, 1–6. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Wilcox, C.S. Oxidative stress and nitric oxide deficiency in the kidney: A critical link to hypertension? Am. J. Physiol. Regul. Integr. Comp. Physiol. 2005, 289, R913–R935. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Luyckx, V.A.; Bertram, J.F.; Brenner, B.M.; Fall, C.; Hoy, W.E.; Ozanne, S.E.; Vikse, B.E. Effect of fetal and child health on kidney development and long-term risk of hypertension and kidney disease. Lancet 2013, 382, 273–283. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Paixão, A.D.; Alexander, B.T. How the kidney is impacted by the perinatal maternal environment to develop hypertension. Biol. Reprod. 2013, 89, 144. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kett, M.M.; Denton, K.M. Renal programming: Cause for concern? Am. J. Physiol. Regul. Integr. Comp. Physiol. 2011, 300, R791–R803. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Tain, Y.L.; Hsu, C.N. Targeting on asymmetric dimethylarginine related nitric oxide-reactive oxygen species imbalance to reprogram the development of hypertension. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2016, 17, 2020. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Racasan, S.; Braam, B.; Koomans, H.A.; Joles, J.A. Programming blood pressure in adult SHR by shifting perinatal balance of NO and reactive oxygen species toward NO: The inverted barker phenomenon. Am. J. Physiol. Ren. Physiol. 2005, 288, F626–F636. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lundberg, J.O.; Weitzberg, E.; Gladwin, M.T. The nitrate-nitrite-nitric oxide pathway in physiology and therapeutics. Nat. Rev. Drug Discov. 2008, 7, 156–167. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kone, B.C. Nitric oxide synthesis in the kidney: Isoforms, biosynthesis, and functions in health. Semin. Nephrol. 2004, 24, 299–315. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cynober, L.; Moinard, C.; De Bandt, J.P. The 2009 ESPEN Sir David Cuthbertson. Citrulline: A new major signaling molecule or just another player in the pharmaconutrition game? Clin. Nutr. 2010, 29, 545–551. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tain, Y.L.; Hsu, C.N. Toxic Dimethylarginines: Asymmetric Dimethylarginine (ADMA) and Symmetric Dimethylarginine (SDMA). Toxins (Basel) 2017, 9, E92. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cardounel, A.J.; Cui, H.; Samouilov, A.; Johnson, W.; Kearns, P.; Tsai, A.L.; Berka, V.; Zweier, J.L. Evidence for the pathophysiological role of endogenous methylarginines in regulation of endothelial NO production and vascular function. J. Biol. Chem. 2007, 282, 879–887. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rodionov, R.N.; Martens-Lobenhoffer, J.; Brilloff, S.; Hohenstein, B.; Jarzebska, N.; Jabs, N.; Kittel, A.; Maas, R.; Weiss, N.; Bode-Böger, S.M. Role of alanine:glyoxylate aminotransferase 2 in metabolism of asymmetric dimethylarginine in the settings of asymmetric dimethylarginine overload and bilateral nephrectomy. Nephrol. Dial. Transplant. 2014, 29, 2035–2042. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Green Version]

- Popolo, A.; Adesso, S.; Pinto, A.; Autore, G.; Marzocco, S. l-Arginine and its metabolites in kidney and cardiovascular disease. Amino Acids 2014, 46, 2271–2286. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Dong, J.Y.; Qin, L.Q.; Zhang, Z.; Zhao, Y.; Wang, J.; Arigoni, F.; Zhang, W. Effect of oral l-arginine supplementation on blood pressure: A meta-analysis of randomized, double-blind, placebo-controlled trials. Am. Heart J. 2011, 162, 959–965. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Nakagawa, T.; Tanabe, K.; Croker, B.P.; Johnson, R.J.; Grant, M.B.; Kosugi, T.; Li, Q. Endothelial dysfunction as a potential contributor in diabetic nephropathy. Nat. Rev. Nephrol. 2011, 7, 36–44. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Tain, Y.L.; Kao, Y.H.; Hsieh, C.S.; Chen, C.C.; Sheen, J.M.; Lin, I.C.; Huang, L.T. Melatonin blocks oxidative stress-induced increased asymmetric dimethylarginine. Free Radic. Biol. Med. 2010, 49, 1088–1098. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kopkan, L.; Cervenka, L. Renal interactions of renin-angiotensin system, nitric oxide and superoxide anion: Implications in the pathophysiology of salt-sensitivity and hypertension. Physiol. Res. 2009, 58, S55–S67. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Schlesinger, S.; Sonntag, S.R.; Lieb, W.; Maas, R. Asymmetric and symmetric dimethylarginine as risk markers for total mortality and cardiovascular outcomes: A systematic review and meta-analysis of prospective studies. PLoS ONE 2016, 11, e0165811. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Goonasekera, C.D.; Rees, D.D.; Woolard, P.; Frend, A.; Shah, V.; Dillon, M.J. Nitric oxide synthase inhibitors and hypertension in children and adolescents. J. Hypertens. 1997, 15, 901–909. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Roseboom, T.; de Rooij, S.; Painter, R. The Dutch famine and its long-term consequences for adult health. Early Hum, Dev. 2006, 82, 485–491. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Luyckx, V.A.; Brenner, B.M. The clinical importance of nephron mass. J. Am. Soc. Nephrol. 2010, 21, 898–910. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Luyckx, V.A.; Brenner, B.M. Birth weight, malnutrition and kidney-associated outcomes—A global concern. Nat. Rev. Nephrol. 2015, 11, 135–149. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- White, S.L.; Perkovic, V.; Cass, A.; Chang, C.L.; Poulter, N.R.; Spector, T.; Haysom, L.; Craig, J.C.; Salmi, I.A.; Chadban, S.J.; et al. Is low birth weight an antecedent of CKD in later life? A systematic review of observational studies. Am. J. Kidney Dis. 2009, 54, 248–261. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Tain, Y.L.; Luh, H.; Lin, C.Y.; Hsu, C.N. Incidence and risks of congenital anomalies of kidney and urinary tract in newborns: A population-based case-control study in Taiwan. Medicine 2016, 95, e2659. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Tain, Y.L.; Joles, J.A. Reprogramming: A preventive strategy in hypertension focusing on the kidney. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2015, 17, 23. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Thompson, L.P.; Al-Hasan, Y. Impact of oxidative stress in fetal programming. J. Pregnancy 2012, 2012, 582748. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Avila, J.G.; Echeverri, I.; de Plata, C.A.; Castillo, A. Impact of oxidative stress during pregnancy on fetal epigenetic patterns and early origin of vascular diseases. Nutr. Rev. 2015, 73, 12–21. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Tain, Y.L.; Huang, L.T.; Hsu, C.N.; Lee, C.T. Melatonin therapy prevents programmed hypertension and nitric oxide deficiency in offspring exposed to maternal caloric restriction. Oxid. Med. Cell Longev. 2014, 2014, 283180. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tain, Y.Y.; Lee, W.C.; Hsu, C.N.; Lee, W.C.; Huang, L.T.; Lee, C.T.; Lin, C.Y. Asymmetric dimethylarginine is associated with developmental programming of adult kidney disease and hypertension in offspring of streptozotocin-treated mothers. PLoS ONE 2013, 8, e55420. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Su, Y.; Bi, J.; Pulgar, V.M.; Figueroa, J.; Chappell, M.; Rose, J.C. Antenatal glucocorticoid treatment alters Na+ uptake in renal proximal tubule cells from adult offspring in a sex-specific manner. Am. J. Physiol. Ren. Physiol. 2015, 308, F1268–F1275. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Gwathmey, T.M.; Shaltout, H.A.; Rose, J.C.; Diz, D.I.; Chappell, M.C. Glucocorticoid-induced fetal programming alters the functional complement of angiotensin receptor subtypes within the kidney. Hypertension 2011, 57, 620–626. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tain, Y.L.; Sheen, J.M.; Chen, C.C.; Yu, H.R.; Tiao, M.M.; Kuo, H.C.; Huang, L.T. Maternal citrulline supplementation prevents prenatal dexamethasone-induced programmed hypertension. Free Radic. Res. 2014, 48, 580–586. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Tain, Y.L.; Hsu, C.N.; Lee, C.T.; Lin, Y.J.; Tsai, C.C. N-Acetylcysteine Prevents Programmed Hypertension in Male Rat Offspring Born to Suramin-Treated Mothers. Biol. Reprod. 2016, 95, 8. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Tain, Y.L.; Wu, K.L.; Lee, W.C.; Leu, S.; Chan, J.Y. Maternal fructose-intake-induced renal programming in adult male offspring. J. Nutr. Biochem. 2015, 26, 642–650. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Tain, Y.L.; Lin, Y.J.; Sheen, J.M.; Yu, H.R.; Tiao, M.M.; Chen, C.C.; Tsai, C.C.; Huang, L.T.; Hsu, C.N. High fat diets sex-specifically affect the renal transcriptome and program obesity, kidney injury, and hypertension in the offspring. Nutrients 2017, 9, 357. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Tain, Y.L.; Hsu, C.N. Interplay between oxidative stress and nutrient sensing signaling in the developmental origins of cardiovascular disease. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2017, 18, 841. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Tain, Y.L.; Huang, L.T.; Lee, C.T.; Chan, J.Y.; Hsu, C.N. Maternal citrulline supplementation prevents prenatal NG-nitro-L-arginine-methyl ester (L-NAME)-induced programmed hypertension in rats. Biol. Reprod. 2015, 92, 7. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Tain, Y.L.; Lee, C.T.; Chan, J.Y.; Hsu, C.N. Maternal melatonin or N-acetylcysteine therapy regulates hydrogen sulfide-generating pathway and renal transcriptome to prevent prenatal N(G)-Nitro-L-argininemethyl ester (L-NAME)-induced fetal programming of hypertension in adult male offspring. Am. J. Obstet. Gynecol. 2016, 215, 636. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tain, Y.L.; Huang, L.T.; Chan, J.Y.; Lee, C.T. Transcriptome analysis in rat kidneys: Importance of genes involved in programmed hypertension. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2015, 16, 4744–4758. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Majzunova, M.; Dovinova, I.; Barancik, M.; Chan, J.Y. Redox signaling in pathophysiology of hypertension. J. Biomed. Sci. 2013, 20, 69. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sheen, J.M.; Yu, H.R.; Tiao, M.M.; Chen, C.C.; Huang, L.T.; Chang, H.Y.; Tain, Y.L. Prenatal dexamethasone-induced programmed hypertension and renal programming. Life Sci. 2015, 132, 41–48. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tain, Y.L.; Hsu, C.N.; Chan, J.Y.; Huang, L.T. Renal transcriptome analysis of programmed hypertension induced by maternal nutritional insults. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2015, 16, 17826–17837. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Tain, Y.L.; Leu, S.; Wu, K.L.; Lee, W.C.; Chan, J.Y. Melatonin prevents maternal fructose intake-induced programmed hypertension in the offspring: Roles of nitric oxide and arachidonic acid metabolites. J. Pineal Res. 2014, 57, 80–89. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Yosypiv, I.V. Renin-angiotensin system in ureteric bud branching morphogenesis: Insights into the mechanisms. Pediatr. Nephrol. 2011, 26, 1499–1512. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Te Riet, L.; vanEsch, J.H.; Roks, A.J.; vanden Meiracker, A.H.; Danser, A.H. Hypertension: Renin-angiotensin aldosterone system alterations. Circ. Res. 2015, 116, 960–975. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Woods, L.L.; Ingelfinger, J.R.; Nyengaard, J.R.; Rasch, R. Maternal protein restriction suppresses the newborn renin-angiotensin system and programs adult hypertension in rats. Pediatr. Res. 2001, 49, 460–467. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wu, L.; Shi, A.; Zhu, D.; Bo, L.; Zhong, Y.; Wang, J.; Xu, Z.; Mao, C. High sucrose intake during gestation increasesangiotensinIItype1receptor-mediatedvascularcontractilityassociatedwithepigeneticalterations in aged offspring rats. Peptides 2016, 86, 133–144. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hsu, C.N.; Wu, K.L.; Lee, W.C.; Leu, S.; Chan, J.Y.; Tain, Y.L. Aliskiren administration during early postnatal life sex-specifically alleviates hypertension programmed by maternal high fructose consumption. Front. Physiol. 2016, 7, 299. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sherman, R.C.; Langley-Evans, S.C. Antihypertensive treatment in early postnatal life modulates prenatal dietary influences upon blood pressure in the rat. Clin. Sci. 2000, 98, 269–275. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Manning, J.; Vehaskari, V.M. Postnatal modulation of prenatally programmed hypertension by dietary Na and ACE inhibition. Am. J. Physiol. Regul. Integr. Comp. Physiol. 2005, 288, R80–R84. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Hsu, C.N.; Lee, C.T.; Huang, L.T.; Tain, Y.L. Aliskiren in early postnatal life prevents hypertension and reduces asymmetric dimethylarginine in offspring exposed to maternal caloric restriction. J. Renin Angiotensin Aldosterone Syst. 2015, 16, 506–513. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jansson, T.; Powell, T.L. Role of placental nutrient sensing in developmental programming. Clin. Obstet. Gynecol. 2013, 56, 591–601. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Efeyan, A.; Comb, W.C.; Sabatini, D.M. Nutrient-sensing mechanisms and pathways. Nature 2015, 517, 302–310. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Green Version]

- Tain, Y.L.; Hsu, C.N.; Chan, J.Y. PPARs link early life nutritional insults to later programmed hypertension and metabolic syndrome. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2015, 17, 20. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Rakhshandehroo, M.; Knoch, B.; Müller, M.; Kersten, S. Peroxisome proliferator-activated receptor α target genes. PPAR Res. 2010, 2010, 612089. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lee, J.; Giordano, S.; Zhang, J. Autophagy, mitochondria and oxidative stress: Cross-talk and redox signaling. Biochem. J. 2012, 441, 523–540. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Komen, J.C.; Thorburn, D.R. Turn up the power-pharmacological activation of mitochondrial biogenesis in mouse models. Br. J. Pharmacol. 2014, 171, 1818–1836. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Valerio, A.; Nisoli, E. Nitric oxide, interorganelle communication, and energy flow: A novel route to slow aging. Front. Cell Dev. Biol. 2015, 3, 6. [Google Scholar]

- Tain, Y.L.; Hsu, C.N. AMP-Activated protein kinase as a reprogramming strategy for hypertension and kidney disease of developmental origin. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2018, 19, 1744. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tain, Y.L.; Lin, Y.J.; Sheen, J.M.; Lin, I.C.; Yu, H.R.; Huang, L.T.; Hsu, C.N. Resveratrol prevents the combined maternal plus postweaning high-fat-diets-induced hypertension in male offspring. J. Nutr. Biochem. 2017, 48, 120–127. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gilbert, J.S.; Nijland, M.J. Sex differences in the developmental origins of hypertension and cardiorenal disease. Am. J. Physiol. Regul. Integr. Comp. Physiol. 2008, 295, R1941–R1952. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Tomat, A.L.; Salazar, F.J. Mechanisms involved in developmental programming of hypertension and renal diseases. Gender differences. Horm. Mol. Biol. Clin. Investig. 2014, 18, 63–77. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Vina, J.; Gambini, J.; Lopez-Grueso, R.; Abdelaziz, K.M.; Jove, M.; Borras, C. Females live longer than males: Role of oxidative stress. Curr. Pharm. Des. 2011, 17, 3959–3965. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hilliard, L.M.; Sampson, A.K.; Brown, R.D.; Denton, K.M. The “his and hers” of the renin-angiotensin system. Curr. Hypertens. Rep. 2013, 15, 71–79. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Mukai, Y.; Ozaki, H.; Serita, Y.; Sato, S. Maternal fructose intake during pregnancy modulates hepatic and hypothalamic AMP-activated protein kinase signalling in a sex-specific manner in offspring. Clin. Exp. Pharmacol. Physiol. 2014, 41, 331–337. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kwekel, J.C.; Desai, V.G.; Moland, C.L.; Vijay, V.; Fuscoe, J.C. Sex differences in kidney gene expression during the life cycle of F344 rats. Biol. Sex Differ. 2013, 4, 14. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tain, Y.L.; Wu, M.S.; Lin, Y.J. Sex differences in renal transcriptome and programmed hypertension in offspring exposed to prenatal dexamethasone. Steroids 2016, 115, 40–46. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Mao, J.; Zhang, X.; Sieli, P.T.; Falduto, M.T.; Torres, K.E.; Rosenfeld, C.S. Contrasting effects of different maternal diets on sexually dimorphic gene expression in the murine placenta. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 2010, 107, 5557–5562. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Baylis, C. Sex dimorphism in the aging kidney: Difference in the nitric oxide system. Nat. Rev. Nephrol. 2009, 5, 384–396. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Satoh, N.; Nakamura, M.; Suzuki, A.; Tsukada, H.; Horita, S.; Suzuki, M.; Moriya, K.; Seki, G. Effects of Nitric Oxide on Renal Proximal Tubular Na(+) Transport. Biomed. Res. Int. 2017, 2017, 6871081. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bianco-Miotto, T.; Craig, J.M.; Gasser, Y.P.; van Dijk, S.J.; Ozanne, S.E. Epigenetics and DOHaD: From basics to birth and beyond. J. Dev. Orig. Health Dis. 2017, 8, 513–519. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Song, R.; Van Buren, T.; Yosypiv, I.V. Histone deacetylases are critical regulators of the renin-angiotensin system during ureteric bud branching morphogenesis. Pediatr. Res. 2010, 67, 573–578. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Al Khodor, S.; Reichert, B.; Shatat, I.F. The microbiome and blood pressure: Can microbes regulate our blood pressure? Front. Pediatr. 2017, 5, 138. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ma, J.; Li, H. The role of gut microbiota in atherosclerosis and hypertension. Front. Pharmacol. 2018, 9, 1082. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Cavanal Mde, F.; Gomes, G.N.; Forti, A.L.; Rocha, S.O.; Franco Mdo, C.; Fortes, Z.B.; Gil, F.Z. The influence of l-arginine on blood pressure, vascular nitric oxide and renal morphometry in the offspring from diabetic mothers. Pediatr. Res. 2007, 62, 145–150. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Koeners, M.P.; Racasan, S.; Koomans, H.A.; Joles, J.A.; Braam, B. Nitric oxide, superoxide and renal blood flow autoregulation in SHR after perinatal l-arginine and antioxidants. Acta Physiol. 2007, 190, 329–338. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Koeners, M.P.; Braam, B.; van der Giezen, D.M.; Goldschmeding, R.; Joles, J.A. Perinatal micronutrient supplements ameliorate hypertension and proteinuria in adult fawn-hooded hypertensive rats. Am. J. Hypertens. 2010, 23, 802–808. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Racasan, S.; Braam, B.; van der Giezen, D.M.; Goldschmeding, R.; Boer, P.; Koomans, H.A.; Joles, J.A. Perinatal l-arginine and antioxidant supplements reduce adult blood pressure in spontaneously hypertensive rats. Hypertension 2004, 44, 83–88. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tain, Y.L.; Hsieh, C.S.; Lin, I.C.; Chen, C.C.; Sheen, J.M.; Huang, L.T. Effects of maternal l-citrulline supplementation on renal function and blood pressure in offspring exposed to maternal caloric restriction: The impact of nitric oxide pathway. Nitric Oxide 2010, 23, 34–41. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chien, S.J.; Lin, K.M.; Kuo, H.C.; Huang, C.F.; Lin, Y.J.; Huang, L.T.; Tain, Y.L. Two different approaches to restore renal nitric oxide and prevent hypertension in young spontaneously hypertensive rats: l-Citrulline and nitrate. Transl. Res. 2014, 163, 43–52. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Koeners, M.P.; van Faassen, E.E.; Wesseling, S.; Sain-van der Velden, M.; Koomans, H.A.; Braam, B.; Joles, J.A. Maternal supplementation with citrulline increases renal nitric oxide in young spontaneously hypertensive rats and has long-term antihypertensive effects. Hypertension 2007, 50, 1077–1084. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hsu, C.N.; Lin, Y.J.; Lu, P.C.; Tain, Y.L. Maternal Resveratrol Therapy Protects Male Rat Offspring against Programmed Hypertension Induced by TCDD and Dexamethasone Exposures: Is It Relevant to Aryl Hydrocarbon Receptor? Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2018, 19, E2459. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Tain, Y.L.; Leu, S.; Lee, W.C.; Wu, K.L.H.; Chan, J.Y.H. Maternal Melatonin Therapy Attenuated Maternal High-Fructose Combined with Post-Weaning High-Salt Diets-Induced Hypertension in Adult Male Rat Offspring. Molecules 2018, 23, E886. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Tai, I.H.; Sheen, J.M.; Lin, Y.J.; Yu, H.R.; Tiao, M.M.; Chen, C.C.; Huang, L.T.; Tain, Y.L. Maternal N-acetylcysteine therapy regulates hydrogen sulfide-generating pathway and prevents programmed hypertension in male offspring exposed to prenatal dexamethasone and postnatal high-fat diet. Nitric Oxide 2016, 53, 6–12. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lin, Y.J.; Lin, I.C.; Yu, H.R.; Sheen, J.M.; Huang, L.T.; Tain, Y.L. Early Postweaning Treatment with Dimethyl Fumarate Prevents Prenatal Dexamethasone- and Postnatal High-Fat Diet-Induced Programmed Hypertension in Male Rat Offspring. Oxid. Med. Cell Longev. 2018, 2018, 5343462. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Tsai, C.M.; Kuo, H.C.; Hsu, C.N.; Huang, L.T.; Tain, Y.L. Metformin reduces asymmetric dimethylarginine and prevents hypertension in spontaneously hypertensive rats. Transl. Res. 2014, 164, 452–459. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Fan, N.C.; Tsai, C.M.; Hsu, C.N.; Huang, L.T.; Tain, Y.L. N-acetylcysteine prevents hypertension via regulation of the ADMA-DDAH pathway in young spontaneously hypertensive rats. Biomed. Res. Int. 2013, 2013, 696317. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Tain, Y.L.; Huang, L.T.; Lin, I.C.; Lau, Y.T.; Lin, C.Y. Melatonin prevents hypertension and increased asymmetric dimethylarginine in young spontaneous hypertensive rats. J. Pineal Res. 2010, 49, 390–398. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wesseling, S.; Essers, P.B.; Koeners, M.P.; Pereboom, T.C.; Braam, B.; van Faassen, E.E.; Macinnes, A.W.; Joles, J.A. Perinatal exogenous nitric oxide in fawn-hooded hypertensive rats reduces renal ribosomal biogenesis in early life. Front. Genet. 2011, 2, 52. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wu, Z.; Siuda, D.; Xia, N.; Reifenberg, G.; Daiber, A.; Münzel, T.; Förstermann, U.; Li, H. Maternal treatment of spontaneously hypertensive rats with pentaerythritoltetranitrate reduces blood pressure in female offspring. Hypertension 2015, 65, 232–237. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, S.C.; Lin, K.M.; Chien, S.J.; Huang, L.T.; Hsu, C.N.; Tain, Y.L. RNA silencing targeting PIN (protein inhibitor of neuronal nitric oxide synthase) attenuates the development of hypertension in young spontaneously hypertensive rats. J. Am. Soc. Hypertens. 2014, 8, 5–13. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Uson-Lopez, R.A.; Kataoka, S.; Mukai, Y.; Sato, S.; Kurasaki, M. Melinjo (Gnetum gnemon) Seed Extract Consumption during Lactation Improved Vasodilation and Attenuated the Development of Hypertension in Female Offspring of Fructose-Fed Pregnant Rats. Birth Defects Res. 2018, 110, 27–34. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sengupta, P. The Laboratory Rat: Relating Its Age with Human’s. Int. J. Prev. Med. 2013, 4, 624–630. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Gokce, N. l-Arginine and hypertension. J. Nutr. 2004, 134, 2807S–2811S. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Romero, M.J.; Platt, D.H.; Caldwell, R.B.; Caldwell, R.W. Therapeutic use of citrulline in cardiovascular disease. Cardiovasc. Drug Rev. 2006, 24, 275–290. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wu, G.; Morris, S.M., Jr. Arginine metabolism: Nitric oxide and beyond. Biochem. J. 1998, 336, 1–17. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Beltowski, J.; Kedra, A. Asymmetric dimethylarginine (ADMA) as a target for pharmacotherapy. Pharmacol. Rep. 2006, 58, 159–178. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Jaffrey, S.R.; Snyder, S.H. PIN: An associated protein inhibitor of neuronal nitric oxide synthase. Science 1996, 274, 774–777. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Interventions | Animal Models | Intervention Period | Species/Gender | Age at Measure (Week) | Protective Effects | Reference |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Substrate for NOS | ||||||

| l-arginine | Maternal streptozotocin-induced diabetes | 3 weeks to 24 weeks | Wistar/M | 24 | Prevented hypertension and glomerular hypertrophy | [84] |

| l-arginine + antioxidants | Genetic hypertension | 2 weeks before until 8 weeks after birth | SHR/Mand F | 9 | Prevented hypertension | [85] |

| l-arginine + antioxidants | Genetic hypertension | 2 weeks before until 4 weeks after birth | FHH/M and F | 36 | Prevented hypertension, proteinuria, and glomerulosclerosis | [86] |

| l-arginine + antioxidants | Genetic hypertension | 2 weeks before until 8 weeks after birth | SHR/M and F | 50 | Prevented hypertension and proteinuria | [87] |

| l-citrulline | Maternal 50% caloric restriction | 3 weeks before until 3 weeks after birth | SD/M | 12 | Prevented kidney damage, increased nephron number | [88] |

| l-citrulline | Maternal nitric oxide deficiency | 3 weeks before until 3 weeks after birth | SD/M | 12 | Prevented hypertension | [46] |

| l-citrulline | Maternal streptozotocin-induced diabetes | 3 weeks before until 3 weeks after birth | SD/M | 12 | Prevented hypertension and kidney damage, increased nephron number | [38] |

| l-citrulline | Prenatal dexamethasone exposure | 3 weeks before until 3 weeks after birth | SD/M | 12 | Prevented hypertension, increased nephron number | [41] |

| l-citrulline | Genetic hypertension | 4 weeks to 12 weeks | SHR/M | 12 | Prevented hypertension | [89] |

| l-citrulline | Genetic hypertension | 2 weeks before until 6 weeks after birth | SHR/M and F | 50 | Prevented hypertension | [90] |

| Asymmetric dimethylarginine (ADMA)-lowering agents | ||||||

| Resveratrol | Prenatal dexamethasone plus TCDD exposure | 3 weeks before until 3 weeks after birth | SD/M | 12 | Prevented hypertension | [91] |

| Melatonin | Maternal high-fructose diet plus post-weaning high-salt diet | 3 weeks before until 3 weeks after birth | SD/M | 12 | Prevented hypertension | [92] |

| Aliskiren | Maternal caloric restriction | 2 weeks to 4 weeks | SD/M | 12 | Prevented hypertension | [60] |

| N-acetylcysteine | Prenatal dexamethasone plus postnatal high-fat diet | 3 weeks before until 3 weeks after birth | SD/M | 16 | Prevented hypertension | [93] |

| Dimethyl fumarate | Prenatal dexamethasone plus postnatal high-fat diet | 3 weeks to 6 weeks | SD/M | 16 | Prevented hypertension | [94] |

| Metformin | Genetic hypertension | 4 weeks to 12 weeks | SHR/M | 12 | Prevented hypertension | [95] |

| N-acetylcysteine | Genetic hypertension | 4 weeks to 12 weeks | SHR/M | 12 | Prevented hypertension | [96] |

| Melatoin | Genetic hypertension | 4 weeks to 12 weeks | SHR/M | 12 | Prevented hypertension | [97] |

| Aliskiren | Genetic hypertension | 4 weeks to 12 weeks | SHR/M | 12 | Prevented hypertension | [61] |

| NO donor | ||||||

| Nitrate | Genetic hypertension | 4 weeks to 12 weeks | SHR/M | 12 | Prevented hypertension | [89] |

| Molsidomine | Genetic hypertension | 2 weeks before until 4 weeks after birth | FHH/M and F | 42 | Prevented hypertension | [98] |

| Pentaerythritol tetranitrate | Genetic hypertension | 3 weeks before until 3 weeks after birth | SHR/M and F | 24 | Prevented hypertension | [99] |

| Others | ||||||

| Short interfering RNA targeting PIN | Genetic hypertension | 4 weeks to 12 weeks | SHR/M | 12 | Prevented hypertension | [100] |

| Melinjo (Gnetum gnemon) Seed Extract | Maternal high-fructose diet | Birth to 3 weeks | Wistar/F | 17 | Prevented hypertension | [101] |

© 2019 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Hsu, C.-N.; Tain, Y.-L. Regulation of Nitric Oxide Production in the Developmental Programming of Hypertension and Kidney Disease. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2019, 20, 681. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijms20030681

Hsu C-N, Tain Y-L. Regulation of Nitric Oxide Production in the Developmental Programming of Hypertension and Kidney Disease. International Journal of Molecular Sciences. 2019; 20(3):681. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijms20030681

Chicago/Turabian StyleHsu, Chien-Ning, and You-Lin Tain. 2019. "Regulation of Nitric Oxide Production in the Developmental Programming of Hypertension and Kidney Disease" International Journal of Molecular Sciences 20, no. 3: 681. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijms20030681