Misdiagnosis of renal pelvic unicentric Castleman disease: a case report

- 1Department of Urology, Jinling Clinical Medical College, Nanjing Medical University, Nanjing, China

- 2Division of Nephrology, Changzheng Hospital, Second Military Medical University, Shanghai, China

- 3Internal Medicine III (Nephrology), Naval Medical Center of PLA, Second Military Medical University (Naval Medical University), Shanghai, China

- 4Department of Nephrology, Shanghai Fourth People’s Hospital, School of Medicine, Tongji University, Shanghai, China

- 5Department of Urology, 8th medical Center of the PLA General Hospital, Beijing, China

- 6Department of Nephrology, Zhabei Central Hospital of JingAn District of Shanghai, Shanghai, China

Castleman disease is a rare heterogeneous lymphoproliferative disorder of unknown etiology. Unicentric Castleman disease (UCD) is more common. UCD can occur at any site where lymphatic tissue exists, most commonly in the mediastinum, neck, and abdominal cavity, etc. in the current study, we reported a 46-year-old woman, who has left low back pain and discomfort. Magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) of the kidneys showed the left renal pelvis was occupied, left hydronephrosis, and the left renal hilum and retroperitoneal lymph nodes were enlarged. Enhanced kidney CT showed that the “pelvic tumor” was moderately enhanced in the bottom part in corticomedullary phase, while in nephrogenic phase, it was unevenly enhanced with a highly enhanced bottom part and weakly enhanced upper part. In excretory phase, reinforcement was decreased. “left renal pelvis tumor” was diagnosed and she underwent surgical treatment with left nephrectomy. However, histopathological examination indicated the UCD. We suggest that for renal pelvic tumors having imaging characteristics of homogeneous soft tissue density and heterogeneous CT enhancement, the hyaline vascular type of UCD could be taken into consideration for differential diagnosis.

Background

Castleman disease also known as angiofollicular lymph node hyperplasia, is a rare heterogeneous lymphoproliferative disorder of unknown etiology (1). First described by Dr. Benjamin Castleman in the 1950 s, this disorder is characterized by the abnormal overgrowth (hyperplasia) of lymphoid tissue, leading to the development of lymph node masses. While the majority of cases are localized and non-life-threatening, there are also systemic forms of the disease that can be more severe and challenging to manage. Three basic pathologic types of this disease could be encountered: hyaline vascular type, plasma cell type, and mixed type. Castleman disease also has been classified into various subtypes based on clinical characteristics, including unicentric and multicentric forms.

Unicentric Castleman disease (UCD) is more common (about 90%), hyaline vascular histopathologic is the leading subtype, and in most cases has no obvious symptoms. The symptoms of the disease are often related to the direct compression of the surrounding tissue (2). Surgical excision can improve the prognosis of patients (3). UCD can occur at any site where lymphatic tissue exists, most commonly in the mediastinum, neck, abdominal cavity, etc. Pararenal localizations are very rare and have been reported to account for 2% of cases (4). In the current study, we reported a 46-year-old woman who had a rare UCD in the renal pelvis, which was easily misdiagnosed as renal pelvis tumors. When renal pelvic tumors had imaging characteristics of homogeneous soft tissue density and heterogeneous CT enhancement, the hyaline vascular type of UCD could be taken into consideration for differential diagnosis.

Case report

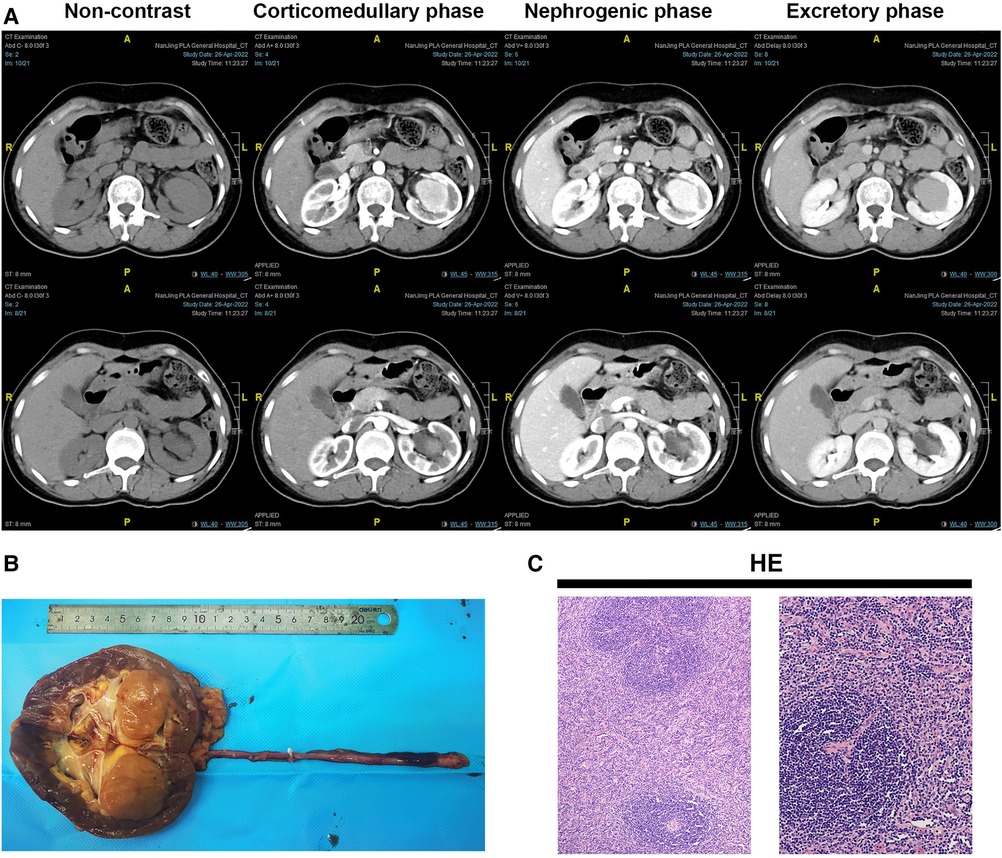

A 46-year-old woman with no known past medical history presented to the urology department with left low back pain and discomfort for 2 weeks on 6 May 2022. CRP was 0.4 mg/L. Levels of ESR, PCT, and IL-6 were all within the normal ranges. Human herpes virus 8 (HHV-8), HIV, HBV, HCV, and syphilis tests were all negative. Urinalysis test and hematuria routines were normal. The patient underwent abdominal computed tomography (CT) scan and found that the left renal pelvis was spherically enlarged and filled with a soft tissue density shadow. Further examination is recommended. The patient then underwent magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) of both kidneys. The results showed the left renal pelvis was occupied, the likely diagnosis was a pelvic tumor, left hydronephrosis, and the left renal hilum and retroperitoneal lymph nodes were enlarged. For differential diagnosis, the patient underwent enhanced kidney CT. The “pelvic tumor” was moderately enhanced in the bottom part in the corticomedullary phase, while in the nephrogenic phase, it was unevenly enhanced with a highly enhanced bottom part and weakly enhanced upper part. In the excretory phase, reinforcement was decreased (Figure 1A). The patient was not accompanied by fever, abdominal pain, gross hematuria, frequent urination, urgent dysuria, etc. The patient was diagnosed with “left renal pelvis tumor” and underwent surgical treatment with a left nephrectomy. Laparoscopic nephroureterectomy was performed by retroperitoneal approach.

Figure 1. Gross view of the left kidney, HE panel, and abdominal enhanced CT scan of the patient. (A) Gross view of the left kidney and ureter; (B) HE panel of the lesion. HE staining showed diffusely proliferating lymphoid tissue, scattered lymphoid follicles with partial atrophy, increased blood vessels between follicles, swelling of endothelial cells, and thickening of the vessel wall with hyaline degeneration. The mantle zone has multiple layers of small lymphocytes arranged in a ring, forming a centripetal ring structure, showing an “onion skin”-like structure (the left picture, X100). The blood vessels between the follicles vertically insert into the germinal center to form a “lollipop"-like follicle (the right picture, X200). (C) The first column was the lower part of the kidney in enhanced CT.

However, in histopathological examination of the left kidney including “tumor” + ureter resection specimens, Castleman disease of the kidney (hyaline vascular type), also known as giant lymph node hyperplasia, was diagnosed with a lesion (size 3.7 cm × 3.5 cm × 3.5 cm, Figure 1B). The lesion involved the renal parenchyma. However, there was no involvement of Castleman disease tissue in the kidney pelvis, perirenal fat capsule, and ureteral resection margin. HE staining showed diffusely proliferating lymphoid tissue, scattered lymphoid follicles with partial atrophy, increased blood vessels between follicles, swelling of endothelial cells, and thickening of the vessel wall with hyaline degeneration (Figure 1C). The immunohistochemistry (IHC) panel showed CD20 (+), CD79a (+), CD3 (+), CD43 (+), CD5 (+), CD21 (+), CD23 (+), CD10 (+), Bcl-2 (3+), Bcl-6 (-), CyclinD1 (-), Ki-67 expression about 10% (+). In situ hybridization of Epstein-Barr virus-encoded RNA (EBER) was negative. Polymerase Chain Reaction (PCR) detection of B lineage gene rearrangement revealed negative IGH and IGK monoclonal bands. The CT of the whole body was performed on the chest and abdomen, and there were no abnormally enlarged lymph nodes and no abnormalities in other parts. PET-CT was not performed after the operation, because it wasn't malignant. Finally, the patient was diagnosed with UCD after systemic Castleman disease was ruled out by clinical systemic examination. Following the nephrectomy, the patient's clinical symptoms improved.

There was no significant change in body weight at one year's follow-up. Tumor biomarkers, such as AFP, CEA, cytoplasmic thymidine kinase 1, and squamous cell carcinoma antigen were all within the normal ranges. Follow-up was performed at 1 month, 3 months, 6 months, 9 months, and 12 months after operation, respectively. All serum and urinary indicators were within normal ranges. Preoperative serum creatinine (scr) was 58.3 µmol/L, while postoperative scr was 84.9 µmol/L, 79.4 µmol/L, and 82.3 µmol/L at 1 month, 9 months, and 12 months, respectively.

Discussion

The presented case of a 46-year-old woman with left low back pain and discomfort highlights the diagnostic challenges and unexpected findings in the evaluation of renal abnormalities. Initially, the patient's symptoms and imaging findings raised suspicion of a pelvic tumor with left hydronephrosis. Like most patients with renal pelvis tumors, there was vague abdominal pain resulting from the abdominal mass. Meanwhile, the mass that compressed the renal pelvis or proximal ureter caused hydronephrosis in this patient. However, further investigations, including MRI and enhanced kidney CT, revealed a different and rare diagnosis: UCD of the kidney, specifically the hyaline vascular type. While Castleman disease typically affects lymph nodes in the chest and abdomen, it can uncommonly involve other sites, including the kidney, as seen in this case.

In this case, the presence of a spherically enlarged left renal pelvis filled with soft tissue density shadow on CT prompted further investigation. The findings from MRI and enhanced kidney CT, such as moderate enhancement in the corticomedullary phase and decreased enhancement in the excretory phase, were consistent with a solid renal mass. Such radiological characteristics could overlap with those of renal cell carcinoma, making the diagnosis more challenging. Diagnostic imaging methods such as ultrasound, CT, and MRI generally are hard to differentiate UCD from other tumors because of lacking specific signs (5). UCD appears as soft tissue density nodules or swelling on plain CT scans with uniform density. In the current case, the lesions were characterized by heterogeneous CT enhancement. The reason for this may be the difference in blood supply from blood vessels in the upper and lower part of the lesion. The characteristic pathology of the hyaline vascular subtype is the proliferation of a large number of small blood vessels in and between the follicles, so a rich capillary network is formed inside the lesion. Even though renal biopsy can be undertaken to assess the tumor malignancy and to help to avoid extensive resection, most surgeons rarely perform the biopsy of an enhancing renal mass (6). Therefore, we suggest that for renal pelvic tumors having characteristics of homogeneous soft tissue density and heterogeneous CT enhancement, the hyaline vascular type of UCD should be taken into consideration.

Histopathological examination and immunohistochemistry played a crucial role in reaching the correct diagnosis. The characteristic features of Castleman disease, including the presence of germinal centers and hyalinized vessels, were observed in the lesion. The immunohistochemistry panel showed the expression of various markers, such as CD20, CD79a, CD3, CD43, CD5, CD21, CD23, CD10, and Bcl-2, which helped distinguish Castleman disease from other conditions like lymphomas. Importantly, HHV-8 and in situ hybridization for EBER was negative, ruling out an association with the virus, which can sometimes be implicated in multicentric Castleman disease. Additionally, PCR detection of B lineage gene rearrangement revealed negative results for IGH and IGK monoclonal bands, further supporting the diagnosis of UCD (7).

The differentiation between unicentric and multicentric Castleman disease is crucial, as the latter carries a more systemic involvement and may require different treatment approaches. In this case, the patient's clinical symptoms significantly improved following the left nephrectomy, which is a standard treatment for localized UCD (7).

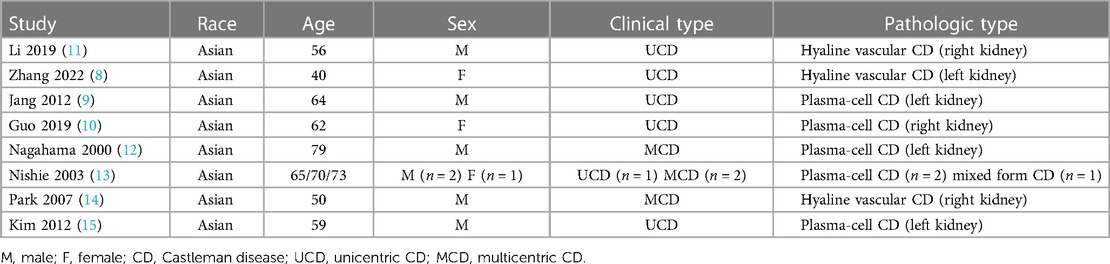

The rarity of Castleman disease and its atypical presentation in the kidney underscore the importance of considering this condition in the differential diagnosis of renal masses. This case report adds to the existing literature on the variable manifestations of Castleman disease and emphasizes the value of imaging and histopathological analysis in arriving at an accurate diagnosis. Since it is rare, few previously published studies reported cases of CD involving the renal sinus (Table 1) (8–15). The presentation of the patients is unspecific in all of the reported cases. The leading subtype was UCD, and the leading histopathological subtypes were HV/PC. What makes this disease interesting is that it has only been reported in Asian populations. The exact reason is unknown.

Overall, this case report serves as a valuable reminder for clinicians to remain vigilant and consider rare entities like Castleman disease when evaluating patients with renal masses, particularly in instances where the typical presentations do not align with the final diagnosis. Further research and case studies are warranted to deepen our understanding of this rare disease and refine the best management strategies for affected individuals.

Data availability statement

The original contributions presented in the study are included in the article/Supplementary Material, further inquiries can be directed to the corresponding author.

Ethics statement

Written informed consent was obtained from the individual(s) for the publication of any potentially identifiable images or data included in this article.

Author contributions

DF, BY and CX: conceptualization, methodology and investigation, formal analysis, writing original draft. ZX and WC: acquisition of data, revising article. ZM and LZ: conception, interpretation of data, revising article. MY, ZL: data collection. All authors contributed to the article and approved the submitted version.

Funding

Innovative technology projects for clinical dignosis and treatment of Jinling Hospital, (grant no. 22LCZLXJS38). Medical innovation research project of Shanghai Science and Technology Innovation Plan (grant no. 22Y11905500), Funding from Naval Medical Center of PLA, Second Military Medical University (grant no. 21M3201, 21M3202).

Conflict of interest

The authors declare that the research was conducted in the absence of any commercial or financial relationships that could be construed as a potential conflict of interest.

Publisher's note

All claims expressed in this article are solely those of the authors and do not necessarily represent those of their affiliated organizations, or those of the publisher, the editors and the reviewers. Any product that may be evaluated in this article, or claim that may be made by its manufacturer, is not guaranteed or endorsed by the publisher.

References

1. Carbone A, Borok M, Damania B, Gloghini A, Polizzotto MN, Jayanthan RK, et al. Castleman disease. Nat Rev Dis Prim. (2021) 7:84. doi: 10.1038/s41572-021-00317-7

2. Herrada J. The clinical behavior of localized and multicentric Castleman disease. Ann Intern Med. (1998) 128:657. doi: 10.7326/0003-4819-128-8-199804150-00010

3. Bucher P, Chassot G, Zufferey G, Ris F, Huber O, Morel P. Surgical management of abdominal and retroperitoneal Castleman’s disease. World J Surg Oncol. (2005) 3:33. doi: 10.1186/1477-7819-3-33

4. Ryu JH, Oh JW, Kim KH, Choi JI, Ryu KH, Kim YJ, et al. Castleman disease misdiagnosed as a neoplasm of the kidney. Korean J Urol. (2009) 50:413. doi: 10.4111/kju.2009.50.4.413

5. Zhao S, Wan Y, Huang Z, Song B, Yu J. Imaging and clinical features of Castleman disease. Cancer Imaging. (2019) 19:53. doi: 10.1186/s40644-019-0238-0

6. Prince HM, Chan K-L, Lade S, Harrison S. Update and new approaches in the treatment of Castleman disease. J Blood Med. (2016) 7:145–58. doi: 10.2147/JBM.S60514

7. van Rhee F, Oksenhendler E, Srkalovic G, Voorhees P, Lim M, Dispenzieri A, et al. International evidence-based consensus diagnostic and treatment guidelines for unicentric Castleman disease. Blood Adv. (2020) 4:6039–50. doi: 10.1182/bloodadvances.2020003334

8. Zhang E, Li Y, Lang N. Case report: Castleman’s disease involving the renal sinus resembling renal cell carcinoma. Front Surg. (2022) 9:1001350. doi: 10.3389/fsurg.2022.1001350

9. Jang SM, Han H, Jang K-S, Jun YJ, Lee TY, Paik SS. Castleman’s disease of the renal Sinus presenting as a urothelial malignancy: a brief case report. Korean J Pathol. (2012) 46:503. doi: 10.4132/KoreanJPathol.2012.46.5.503

10. Guo X-W, Jia X-D, Shen S-S, Ji H, Chen Y-M, Du Q, et al. Radiologic features of Castleman’s disease involving the renal sinus: a case report and review of the literature. World J Clin Cases. (2019) 7:1001–5. doi: 10.12998/wjcc.v7.i8.1001

11. Li Y, Zhao H, Su B, Yang C, Li S, Fu W. Primary hyaline vascular Castleman disease of the kidney: case report and literature review. Diagn Pathol. (2019) 14:94. doi: 10.1186/s13000-019-0870-9

12. Nagahama K, Higashi K, Sanada S, Nezumi M, Itou H. Multicentric Castleman’s disease found by a renal sinus lesion: a case report. Hinyokika Kiyo. (2000) 46:95–9.10769797

13. Nishie A, Yoshimitsu K, Irie H, Aibe H, Tajima T, Shinozaki K, et al. Radiologic features of Castleman’s disease occupying the renal sinus. Am J Roentgenol. (2003) 181:1037–40. doi: 10.2214/ajr.181.4.1811037

14. bean Park J, Hwang JH, Kim H, Choe HS, Kim YK, Kim HB, et al. Castleman disease presenting with jaundice: a case with the multicentric hyaline vascular variant. Korean J Intern Med. (2007) 22:113. doi: 10.3904/kjim.2007.22.2.113

Keywords: Castleman disease, renal tumor, diagnosis, computerized tomography, imaging

Citation: Fu D, Yang B, Yang M, Xu Z, Cheng W, Liu Z, Zhang L, Mao Z and Xue C (2023) Misdiagnosis of renal pelvic unicentric Castleman disease: a case report. Front. Surg. 10:1225890. doi: 10.3389/fsurg.2023.1225890

Received: 20 May 2023; Accepted: 18 August 2023;

Published: 31 August 2023.

Edited by:

Pasquale Cianci, Azienda Sanitaria Localedella Provincia di Barletta Andri Trani (ASL BT), ItalyReviewed by:

Makoto Ide, Takamatsu Red Cross Hospital, JapanVincenzo Lizzi, Azienda Ospedaliero-Universitaria Ospedali Riuniti di Foggia, Italy

© 2023 Fu, Yang, Yang, Xu, Cheng, Liu, Zhang, Mao and Xue. This is an open-access article distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution License (CC BY). The use, distribution or reproduction in other forums is permitted, provided the original author(s) and the copyright owner(s) are credited and that the original publication in this journal is cited, in accordance with accepted academic practice. No use, distribution or reproduction is permitted which does not comply with these terms.

*Correspondence: Cheng Xue chengxia1568@126.com; xuecheng@smmu.edu.cn Liming Zhang zlm198291@163.com Zhiguo Mao maozhiguo518@126.com

†These authors have contributed equally to this work

Dian Fu

Dian Fu Bo Yang

Bo Yang Ming Yang4,†

Ming Yang4,†  Zhenyu Xu

Zhenyu Xu Wen Cheng

Wen Cheng Zhiguo Mao

Zhiguo Mao Cheng Xue

Cheng Xue