The role of sexism in holding politicians accountable for sexual misconduct

- Department of Social and Political Sciences, Philosophy, and Anthropology, Faculty of Humanities, Arts and Social Sciences, University of Exeter, Exeter, United Kingdom

Experimental research on the impact of the #MeToo movement on the evaluation of politicians has focused on how the impact is conditioned by partisan motivation. Beyond partisanship, gender identity and sexist attitudes may also act as a barrier to the success of #MeToo in challenging sexual misconduct in politics. In a conjoint experiment, we examine the extent to which sexism and gender identities (feminine/masculine identity and self-identified gender) condition how individuals respond to politicians accused of sexual misconduct. Respondents were shown two profiles of fictional British male candidates accused of sexual misconduct where the characteristics of the candidate and the scandal were (the number of allegations made, whether they apologized for the misconduct, their partisanship, and their stance on Brexit). We find that in general, more severe misconduct has a more negative impact on evaluations but that respondents who expressed attitudes consistent with hostile sexism were less likely to punish politicians for multiple offenses and less likely to reward a recognition of wrongdoing. Categorical gender identity, whether the respondent was a man or a woman, did not condition the electoral consequences of the scandal and a feminine and masculine identities moderated the impact of the political stance of the candidate. We conclude by discussing the importance of measuring gender attitudes, especially sexism and non-categorical measures of gender identity, in future studies on the political consequences of #MeToo.

1. Introduction

The #MeToo movement, launched by Tarana Burke in 2006, is an intersectional project to support women and girls of color who have experienced sexual violence (Pellegrini, 2018). With the revelations of rape and sexual assault by Hollywood director Harvey Weinstein, actor Alyssa Milano encouraged social media user to adopt the #MeToo hashtag as a rallying cry for victims of sexual misconduct. Following the mobilization of the #MeToo movement, several politicians in the US such as Al Franken (in 2018) and John Conyer (in 2017) resigned due to allegations of sexual misconduct. While these high-profile resignations and legal cases give evidence of the movement's success, some are more cautious about the lasting impact because the focus has been on high profile, celebrity cases and the media has been unduly positive about the impact (Rosewarne, 2019). Beyond these hurdles, sexist attitudes that minimize the experiences of women, could also prevent the movement from changing how we treat perpetrators of sexual assault and those guilty of sexual misconduct (Archer and Kam, 2020).

Much of the research on #MeToo and its political consequences has focused on the United States but we turn our attention to Britain. Awareness of the movement in Britain is reasonably high, with 55% of both men and women surveyed having heard of the movement at the time of our study (YouGov, 2019), and perhaps more significantly, “over half of women aged 18–34, and 58% of young men say they have been more willing to challenge behavior or comments they think are unacceptable” [Fawcett Society, (2018, October 2), p. 1]. Allegations against British MPs followed those in the US in 2017 with Secretary of State for Defense Michael Fallon resigning after being accused of sexual misconduct. Then Prime Minister Theresa May called for a change in procedures for reporting and discipling acts of sexual misconduct. Despite there being high awareness of the movement, less than half (45%) of people believe that the campaign has positively impacted women (YouGov, 2019). Despite this level of support, what types of attitudes may stall progress of the movement, prevent the public from holding guilty politicians accountable or, even, drive a backlash against #MeToo movement? We address this question by considering the role of gender attitudes that endorse negative, traditional, and stereotyped views of women.

We discuss below the potential for sexual misconduct scandals to have electoral consequences for politicians. This review of past research allows us to propose several expectations about how these electoral consequences can be moderated by gendered attitudes. Attitudes about gender, in particular hostile sexism which indicates negativity toward women who violate traditional gender norms, can shape views of politicians and we test below how they condition the electoral consequences of sexual misconduct allegations.

2. Electoral consequences of sex scandals

Political scandals are a regular part of contemporary politics and maintaining political accountability during scandals is a test for a healthy democracy. When political scandals are exposed and the corrupt politicians resign or are turned out by voters, democratic legitimacy is enhanced but the failure to hold these political actors accountable can signal a weakness in democracy. Research does show that when politicians transgress the norms of legitimate and legal behavior, they tend to lose votes (Banducci and Karp, 1994; Maier, 2011) and scandals in general tend to have a negative impact on trust in politicians and political institutions (Bowler and Karp, 2004). Are sex scandals different? Past political sex scandals involving marital infidelity, such as the one involving President to Bill Clinton and Monica Lewinsky (in 1998), rather than detracting from Clinton's approval coincided with an increase due to a booming economy (Zaller, 1998). Those involved in political or economic scandals are judged more harshly than those involved in moral or sexual scandals, potentially due to the former being more relevant to their job (Doherty et al., 2014). Other evidence suggests that the nature of the scandal, whether in a politician's private or public life, does not seem to make a difference with perhaps the exception of France (Sarmiento-Mirwaldt et al., 2014). However, due to increased awareness and mobilization of the #MeToo movement, the consequences of accusations of sexual misconduct in the political realm are driven by a different partisan dynamic that has developed over the past 25 years since Clinton and Lewinsky (Holman and Kalmoe, 2021). For example, how victims view sexual consent has evolved. Monica Lewinsky herself reconsidered the consensual nature of her relationship with Bill Clinton to recognize that the power differential between a president and an intern means “the idea of consent might well be rendered moot” (Lewinsky, 2018, para 33).

We build on the partisan motivated reasoning research on the electoral consequences of #MeToo and sexual misconduct allegations to examine the impact of sexual misconduct allegations in Britain. Our primary focus is on how gender attitudes and identity condition responses to sexual misconduct allegations. Specifically, we test whether gender identity and hostile sexism – overtly negative attitudes about women – mitigate the negative impact of allegations by women against male politicians. We examine this moderating effect across four attributes of the sexual misconduct scandal – the candidate's reaction, the severity of the allegations, the time passed and whether the candidate accepts blame. By examining these relationships in Britain, we provide a test of their effect where politics are less personalized. Outside the personalized politics of the US, these types of allegations may have less of an impact. By drawing together the research that has focused on the impact of attributes of sexual misconduct and the research that has focused on heterogeneous effects among study participants, we outline below how the conditioning impact of gender attitudes, such as hostile sexism, might vary across attributes. For example, a respondent whose identity is invested in #MeToo is both more likely to punish but also more likely to respond to outright apologies. On the other hand, those who are likely to dismiss #MeToo accusations because they are inconsistent with one's gender attitudes are less likely to punish but more likely to punish the politician when he denies the allegations.

3. Sexual misconduct allegations: hostile sexism, context and candidate evaluations

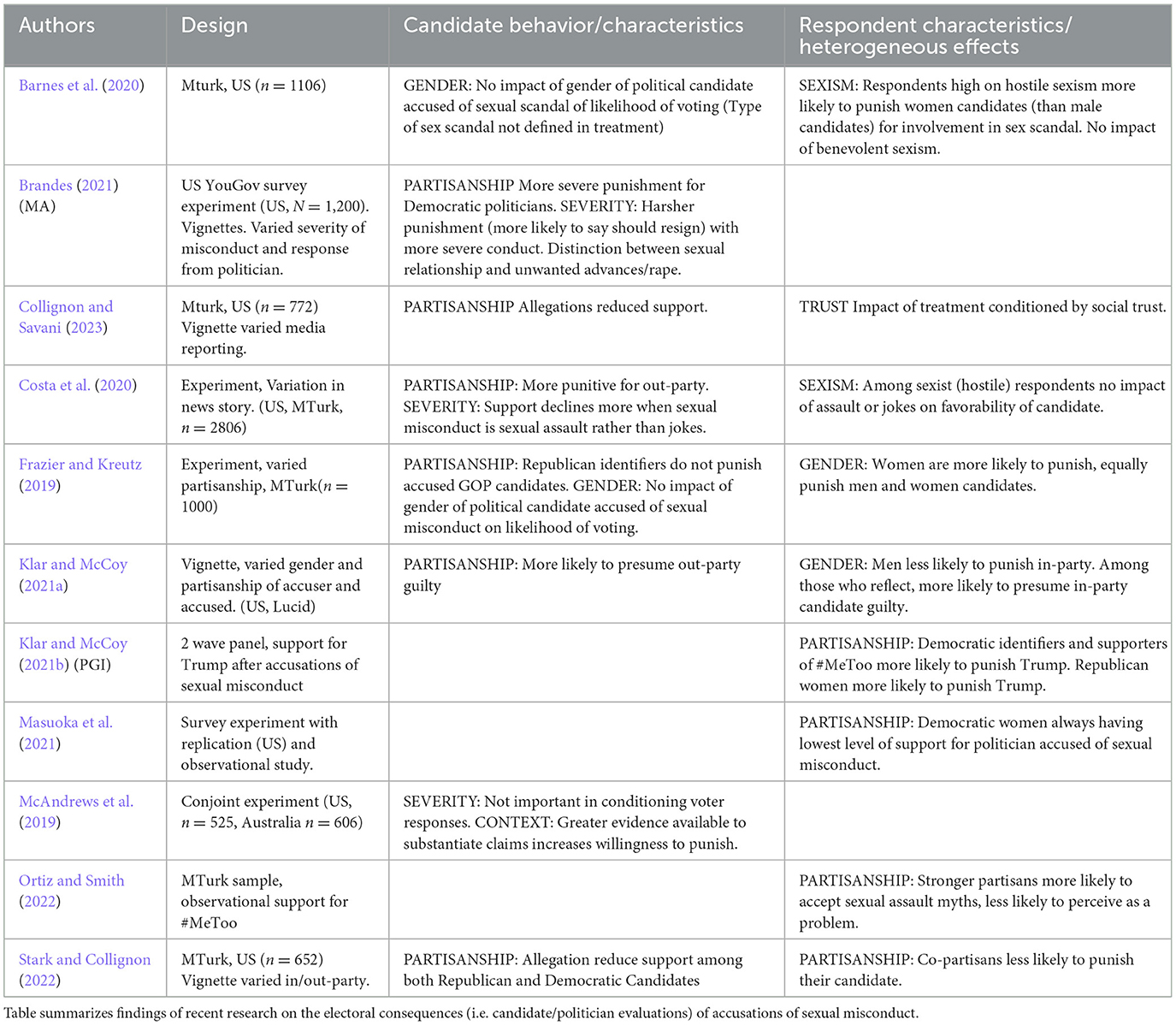

While other studies have examined sex scandals, such as Vonnahme (2014) who demonstrates the immediate but unenduring liability of accusations related to an extramarital affair, our analysis centers on sexual misconduct rather than sex scandals in general. Additionally, unlike Barnes et al. (2020) who show that women candidates provoke negative reactions from sexist respondents when engaged in a sex scandal, we limit our analysis to sexual misconduct allegations against male politicians. Table 1 summarizes existing studies about #MeToo allegations against politicians that we build on. In particular, we draw on those studies Barnes et al. (2020) and Costa et al. (2020) – that also question how gender attitudes (e.g., sexism) condition responses to allegations. Below we provide a theoretical framework for examining how gender attitudes and identity shape the way individuals punish (or fail to punish) politicians for sexual misconduct.

Table 1. Summary of #MeToo experimental studies - candidate behavior, characteristics and heterogeneous effects.

We know that some politicians seem to be immune to allegations. For example, despite Trump's sexually violent language this did “nothing to prevent him winning the votes of a majority of white women” (Smith, 2019) with some concluding that the use of #MeToo as an awareness raising implement has been reasonably well received, but its use as a political tool has been said to be “conspicuously ineffective” (Matthews, 2019). Recent research on the electoral consequences of scandal has been driven by the partisan motivated reasoning framework and examines whether co-partisan candidates are less likely to be punished. The motivated reasoning framework suggests that the desire to reach conclusions supportive of prior attitudes or beliefs may limit or override any accuracy motivations, resulting in accurate information that is at odds with predispositions being diluted, ignored, or even reinterpreted as supportive to the extent that views are strengthened in the face of contradictory information (Kunda, 1990). Thus, when co-partisan politicians are accused of sexual misconduct, this information may be discounted when evaluating the political actor. Research exploring motivated reasoning and #MeToo does shows that partisans are more likely to view politicians from another party as guilty of sexual misconduct (Klar and McCoy, 2021a), partisans are more likely to resist these allegations when evaluating preferred politicians (Klar and McCoy, 2021b), those aligned with parties on the left are more likely to believe sexual misconduct allegations about politicians (Craig and Cossette, 2022) and this is particularly true among women on the left (Masuoka et al., 2021).

The framework of partisan motivated reasoning draws attention to how partisanship can provide a lens by which to judge politicians accused of misconduct but attitudes about the role of women, one's own experiences of discrimination or gender-based violence and one's own sense of gender are also predispositions shaping attitudes to actors and events that are at the intersection of gender and politics. On the one hand, we can ask whether there are limitations to partisan reasoning (Costa et al., 2020) such that those who hold more gender equal attitudes, for example, may not forgive co-partisans. Or those who hold sexist views will be less likely to punish politicians accused of sexual misconduct. For example, sexist attitudes – held by both men and women – and the salience of gender identity can explain why white women did not punish Trump for his sexualised and misogynistic language (Ratliff et al., 2019).

The research summarized in Table 1 has found that gender relevant attitudes other than partisanship can shape whether voters punish politicians. Support for the #MeToo movement (Klar and McCoy, 2021a; Craig and Cossette, 2022) can increase willingness to punish those accused of sexual misconduct whereas hostile sexism can decrease the willingness to punish (Costa et al., 2020). Collignon and Savani (2023) find that higher motivational values relating to universalism and benevolence increase the inclination to withdraw support from a candidate accused of sexual misconduct. Costa et al. (2020) show that sexism, relative to partisanship, has a strong influence on willingness to punish politicians accused of sexual misconduct and suggest we need to consider gender attitudes such as sexism to understand the impact on #MeToo on the ability of elections to hold accused politicians accountable. We build on the work of Costa et al. (2020) but rather than compare the impact of sexism relative to partisanship we expand the range of gender attitudes examined.

3.1. Hypotheses

Below we detail three gender related factors that we hypothesize will influence the weight given to sexual misconduct in vote choices: gender identity, hypermasculinity and sexism. We develop how gender identity, feminine/masculine identities and sexist attitudes structure responses to sexual misconduct by candidates by providing a legitimizing ideology (Jost, 2019; Barnes et al., 2020).

3.2. Gender identity

There is some research suggesting that women may be more likely than men to judge political candidates harshly when it comes to issues related to sex and gender. One possible explanation for this gender difference is that women may have a stronger sense of empathy and concern for victims of sexual harassment and assault, which could make them more likely to be critical of politicians who are accused of engaging in such behavior. Additionally, women may be more attuned to gender inequality and sexism in society, and thus more likely to be critical of politicians who are seen as perpetuating these problems.

Whilst men can also be victims of sexual harassment, women are significantly more likely to experience sexual harassment and be victims of sexual violence, with the majority of perpetrators being men (UK Parliament, 2018). Estimates by the United Nations are that up to 50% of women in European Union countries have experienced sexual harassment at work (Criado-Perez, 2019), and a study at UK Universities found that 56% of students had experienced unwanted sexual harassment and sexual assault, with 49% of women surveyed stating that they had been touched inappropriately (Batty, 2019). This reality leads to greater resistance among men who are more dismissive of sexual assault claims than women (Szekeres et al., 2020). Attitudinally, men are shown to be more tolerant of sexual harassment than women, which is unsurprising given that women are significantly more likely to be victims of it (Russell and Trigg, 2004). Men also are shown to underestimate the level of sexual harassment experienced by women, with British men underestimating levels by an average of 18%, with women underestimating also, but to a lesser extent (9%) (Duncan and Topping, 2018). Also, women are more likely to perceive sexual assault as a problem and less likely to believe sexual assault myths (Ortiz and Smith, 2022). Negative statements about the movement by men may reflect gender differences in reactions to the campaign (Kunst et al., 2019). These gender differences demonstrate both greater empathy for women as victims of sexual assault and greater risk of sexual assault. This is likely to translate into punishing candidates more for sexual misconduct than men.

Whereas, Barnes et al. (2020) find that women are more likely to punish candidates for scandals they find that the punishment is harsher for women candidates, theorizing that norm violating women suffer. Democratic women voters always rate House incumbents who have been accused of harassment lower—regardless of whether they share the same party or are from the opposing party. Similarly, women, especially Democratic women, viewed the sexual misconduct of Trump more harshly (Lawless and Fox, 2018).

Here we can also draw on theoretical frameworks such as system justification theory (Jost, 2019) that suggest that individuals may defend existing social, economic, and political arrangements inequalities to reduce dissonance or anxiety. Even if individuals experience personal discrimination, beliefs about social structures can underlie passive acceptance of existing inequalities and prejudice, particularly when challenging the status quo can be costly. In a study on rape culture and willingness to report and punish for rape (Schwarz et al., 2020) find that factors related to the victim (e.g., race, gender, attire at time of attack) and the perpetrators (profession) played an important role. Indeed, research suggests that women are more likely than men to perceive behavior as sexual misconduct (Rotundo et al., 2001), and that men are more tolerant of sexual harassment than women (Russell and Trigg, 2004). This leads to our first hypothesis:

H1: Those who identify as women will be more likely to punish candidates accused of sexual misconduct.

3.3. Hypermasculinity and hyperfemininity

Recently scholars of gender and politics have recommended moving beyond categorical measures of gender. Self-expressions of femininity and masculinity allow for a more nuanced understanding of how individuals perceive their gender identities. Drawing on social identity theory, individuals who are polarized in their conceptions of their own masculine and feminine traits [i.e., hypermasculinity and hyperfemininity, see Gidengil and Stolle (2021)] are more likely to draw on these conceptions for the basis of attitudes and preferences. Hypermasculinity and hyperfemininity, extreme or exaggerated forms of masculinity and femininity, indicate adherence to rigid gender roles and stereotypes. On the other hand, individuals who are more fluid in conceptions of their own masculine or feminine traits (put themselves closer to the midpoint on both) are likely to draw on core values that reflect this more fluid conception such as such as openness and diversity.

Hypermasculine individuals may feel particularly threatened by social changes that serve to weaken male dominance. Similarly, hyperfeminine women in their adherence to traditional gender roles might also feel threatened by the decline of the patriarchy. Extant research suggests that these scales demonstrate that femininity and masculinity are good measures of non-categorical gender even though strongly correlated to categorical gender (Gidengil and Stolle, 2021) and are important for understanding variation in important social attitudes, such as those related to social anxiety (Wängnerud et al., 2019). Furthermore, those who have polarized identities – hypermasculine or hyperfeminine – may, in order to reduce anxieties, be more likely to legitimate current structural factors such as women being victims of sexual misconduct. In this way hypermasculine and hyperfeminine identities and attitudes can structure responses to allegations through acceptance of sexual harassment or assault of women as an existing social arrangement. Schermerhorn and Vescio (2022) in a study using the related concept of hegemonic masculinity found that both men and women who endorsed the notion of hegemonic masculinity led to more positive evaluations of Supreme Court Justice Kavanaugh and more negative evaluations of the women who made accusations of sexual assault. Drawing on the argument about how the #MeToo movement represents a threat to male dominance, we hypothesize that:

H2: Individuals with polarized gender identities (e.g. hypermasculine and hyperfeminine) will be less more sympathetic to candidates accused of sexual misconduct.

3.4. Hostile sexism

Hostile sexism is related to a number of attitudes relevant to sexual misconduct such as belief that victims of sexual assault wanted sex (Barreto and Doyle, 2022). Hostile sexism represents antagonistic attitudes toward and beliefs about women, expressed in an obvious and often negative fashion (Glick and Fiske, 1996). It aims to preserve men's dominance over women by underlining men's power and is often resentful toward women who violate what are seen as stereotypical or traditional gender roles (Mastari et al., 2019). Hostile sexism is associated with “greater tolerance of sexual harassment, increased moral disengagement from sexual harassment, and even a higher proclivity to commit sexual assault” (Kunst et al., 2019). Those who endorse hostile sexist beliefs may be less likely to see sexual misconduct as a serious problem or to view victims of sexual harassment or assault sympathetically. Hostile sexism may influence the perception of the perpetrators of sexual assault.

A number of studies have demonstrated how hostile sexism mobilizes support for populist candidates like Trump (Schaffner et al., 2018), policies like Brexit (Green and Shorrocks, 2023) and voting for parties on the right (de Geus et al., 2022). The evidence for the role of sexism in moderating attitudes is not clear cut. Barnes et al. (2020) shows that hostile sexism has a negative impact on evaluation for candidate accused of sex scandals but only if the candidate is a woman. Whereas we only examine sexual misconduct among male candidates, we hypothesize that:

H3: Those who hold hostile sexist attitudes are less likely to punish politicians for sexual misconduct.

Before moving to a discussion of the data and methods, we briefly discuss the attributes of the sexual misconduct scandal we use in our conjoint experiment. We draw on the research summarized in Table 1 to identify salient attributes about sexual misconduct scandals (candidate behavior and characteristics). Table 1 illustrates on the features of the scandal such as the behavior of politicians, the severity of the allegations and the attitudes of individuals. While our focus is on how gender attitudes moderate the impact of sexual misconduct on holding politicians accountable, we explain our choice of attributes and how they potentially interact with gender. Because we hypothesize that gender attitudes will moderate the effect of them, we briefly describe the reasoning behind each of these attributes.

How politicians respond to the allegations are also important in influencing responses. Schlenker (1980) theory of impression management suggests that people anticipate how their behavior will be seen, and how it will affect others, and then attempt to mitigate those effects, controlling the outcome. This “impression management”, denial rather than apologizing, is effective in reducing the negative consequences of allegations of misconduct (Sigal et al., 1988). When accusations of sexual misconduct are easily dismissed, denials of the accusation are seen more favorably in the eyes of the public than an apology and signs of effective impression management (Sigal et al., 1988; Costa et al., 2020). Schlenker (1980) argues that apologies are ineffective because of this dynamic and create negative consequences for politicians accused of scandal (Sigal et al., 1988). Other forms of apology, such as older perpetrators lamenting on the difference in social norms, is another way of apologizing, though again – this does also represent an admission of guilt.

Sexual misconduct can be a strong signal to voters that politicians lack character or are untrustworthy (Doherty et al., 2014). However, these signals can be weak or strong depending on features of the accusations. We examine two in particular: time passed since the events and the severity based on the number of women affected. Studies have shown that the “passage of time is likely to weaken the extent to which voters view the scandal as a signal of the politician's true character” (Doherty et al., 2014, p. 358), and this is particularly true for ‘moral' scandals, including those involving sex. The findings on the severity of allegations summarized in Table 1 points to different conclusions. Using a conjoint experiment, McAndrews et al. (2019) find that more extreme accusations (e.g., sexual assault versus comments) do not necessarily reduce electoral support but that more victims does. Brandes (2021) finds that more extreme accusations do indeed attract greater punishment.

Two salient political attitudes in Britain are party affiliation and Leave/Remain support (Hobolt et al., 2021). The vote to leave the European Union in 2016 revealed deep social divides, which didn't follow traditional party lines (Sobolewska et al., 2019). The slim margin, along with the divisiveness of the issue has caused the UK to become “deeply divided on all alternatives to EU membership”, with no stable majority for any one approach (Dunin-Wasowicz, 2018). Very few people have changed their minds about Brexit, according to current polling data (Hobolt et al., 2018), and it is considered that Brexit has given rise to new political identities. As with traditional partisan identities, “these newly formed Brexit identities have consequences for how people view the world” that impact economics, views on prejudice, and that of nationalism (Hobolt et al., 2021).

4. Data and methods

The data used in this paper was collected by an online survey (20–22 May 2019, N = 1802)1 using the Dynata panel targeting a diversity of respondents, representative of the UK as of its 2011 census. We employed a quota sampling method based on age, gender, and region. The online survey was conducted just prior to the 2019 European Parliament election. It was the last European election to be held in the UK before the leaving the European Union on 31 January 2020. In addition to our conjoint experiment, we asked respondents a series of questions about the party preferences, evaluations of government and political attitudes. Our target sample size for the study1 was 1,500 to allow us for a minimum detectable effect size of ~5% for a four-level attribute experiment across five discrete choice tasks. We recruited beyond this minimum sample size, so we are able to detect smaller effect sizes.

4.1. Conjoint experiments

Conjoint experiments, also known as discrete choice experiments (DCEs), are used to measure the value people place on different attributes of a service or products. Conjoint experiments allow researchers to estimate the effects of multiple components at the same time and can closely approximate the real-world behavioral benchmark (Hainmueller et al., 2014). The use of conjoint analysis is a common tool for studying political preferences and “disentangles patterns in respondents' favourability toward complex, multidimensional objects, such as candidates or policies” (Leeper et al., 2020, p. 207). The purpose of this conjoint experiment is to evaluate how people in the UK judge politicians who have been accused of sexual assault, and how this judgment impacts their vote choice and candidate likeability. Through this experiment, we aimed to establish what parameters are important in the judgement of those accused, as well as how dimensions like the gender and partisanship of respondents affected their opinion.

For the experiment, respondents in the online panel were shown a screen with the prompt: “We would now like to get your opinion on hypothetical candidates for political office. We will ask you to choose one of two candidates described. Please read the descriptions of two potential political candidates.” They were then shown the profile of two candidates. The two profiles of candidates for the House of Commons, all with randomized attributes, included: date of incident (2 years ago, or 20 years ago), number of women who made accusations of sexual misconduct (one woman, several women), the response of the candidate to the allegations made (apologized stating that “times were different”, apologized stating that “what I did was wrong”, and denied the accusations altogether), their stance on Brexit (campaigned to leave, campaigned to remain), and his political party (the Conservative Party, or the Labour Party).

The conjoint experiment allowed for two ways for respondents to show “candidate preference”. We asked for a binary choice between the two profiles with the question: “Which of the two candidates you would personally prefer to see elected to the House of Commons?” The second asked respondents to rate each candidate out of 10 (“On a scale from 1 to 10, where 1 indicates “not at all likely” and 10 indicates “very likely”, what is your likelihood of voting for candidate 1?”), rating their ‘likelihood of voting' for each candidate.

Our choice of five attributes about the scandal and the politician is based on a maximum number of recommended attributes. Exceeding six or seven attributes entails an increased cognitive burden put on the respondents, leading to cognitive shortcuts in evaluating profiles and making choices (Kirkland and Coppock, 2018). There are also certain restrictions for the number of levels per attribute, as the more levels are inspected, the larger the sample size should be to detect the statistically significant effects.

Prior to the conjoint experiment, we measured a series of attitudes to test our hypotheses about the moderating impact of gender attitudes.

4.2. Gender and masculine/feminine identities

We use two approaches to measuring gender identity to capture a fuller range of the identities as a single binary measure may not be appropriate for all populations. First, we use self-expressed gender identity using the question: “How would you describe yourself?”2 Second, we move beyond the categorical measure of gender. Scholars working with survey measures of gender identity have approached the measurement of non-categorical gender with the use of two scales that do not impose stereotypical definitions of femininity and masculinity (Wängnerud et al., 2019).

The question we use is: “We would now like to ask you questions about gender identity. Any one person—woman or man—can have feminine and masculine traits. In general, on each scale, how do you see yourself?” Respondents then assess their characteristics on two scales, one for masculine and another for feminine characteristics. Each scale ranges from 1 = “Not at all feminine/masculine,” to 7= “Very feminine/masculine.” These are the same scales used by Gidengil and Stolle (2021) to create a bidimensional scale – it contains two different dimensions with each one measured separately and does not assume that femininity is the opposite of masculinity. In other words, respondents rate themselves on both masculine and feminine characteristics and are not given any instructions as to what constitutes “male” or “female” characteristics. From the feminine and masculine scales, we created a categorical measure of polarization in gender identities similar to Gidengil and Stolle (2021). Respondents scoring high on masculinity (6, 7) but low on femininity (1, 2) were coded as “hypermasculine” (n = 417, 25%) while those similarly high on femininity and similarly low on masculinity were coded as “hyperfeminine” (n = 428. 25%). We then created categories of weak femininity (3, 4, 5 on feminine scale and lower than 3 on masculine scale with n = 328, 19%) and the opposite scores for weak masculinity (n = 317, 19%). Those who scored themselves at the center on both scales were coded as undifferentiated (n = 197, 12%).3 There is a high correlation between respondent's self-reported categorical gender identity and the bidimensional scale. Among those who identity as women, 49% are hyperfeminine [compared to 45% in Gidengil and Stolle (2021), for example] and 34% as weak feminine. Among men, 51% are hypermasculine and 32% are weak masculine.

4.3. Hostile sexism

There is a battery of items from the ambivalent sexism inventory that measure hostile sexism (Glick and Fiske, 2001). In the survey we asked three items from the hostile sexism index: “Women who complain about sexual harassment cause more problems than they solve”; “For most women, equality means seeking special favors, such as hiring policies that favor them over men”; “Most women interpret innocent remarks or acts as being sexist”. Respondents are asked to express agreement or disagreement with these items (response categories ranged from “Strongly Agree” to “Strongly Disagree” with “Neither Agree or Disagree” as the midpoint. Respondents were also offered a “Don't Know” option).4 High scores indicate agreement with the statements, and we take the average agreement with these as a measurement of hostile sexist attitudes. For the analysis we have created three categories. Those respondents who were one standard deviation above the mean on this scale are labeled as high on hostile sexism with this one standard deviation below the mean are labeled as low on hostile sexism. In our sample, 31% scored high on hostile sexism while 19% scored low on hostile sexism.

5. Results

Our analysis proceeds by estimating the overall effect of the attributes and levels from the conjoint experiment analyzing both discrete choices (left panel of figures) and ranking evaluations (right panel of figures). For our analysis of the conjoint experiment, we used the cregg package by Leeper (2020) to calculate both the average marginal component effects (AMCE) and the marginal means. The AMCE can be interpreted as indicators of “causal effect” coefficients. The AMCE is calculated by taking the average of the marginal component effects (MCEs) for each level of an attribute, weighted by the proportion of times that level was included in the experiment. The MCE is the change in preference score associated with a one-unit change in an attribute level, holding all other attributes constant. Thus, the AMCE provides information on the relative importance of each attribute (relative to the baseline category) for respondents and can be used to rank the attributes by importance. The baseline level was the default generated by the estimation procedure.

We also report the marginal means that how the overall favourability of an attribute with the mean support (0 to 1). Marginal means then can provide a descriptive account of the attributes in our sample and give an indication of the mean outcome of an attribute, such that means with averages above the midpoint indicate a positive effect on infection treatment preference and below the midpoint indicates a negative effect. We then analyse the impact of attributes for our subgroups of interests (i.e., gender, polarized gender identities and hostile sexism) to test our hypothesized moderation impact of gender attitudes. For subgroup analysis we rely on estimations of the marginal means. For the subgroup analysis we rely only on the marginal means because they are the preferred method for comparing sub-group differences due to the sensitivity of AMCE to the choice of baseline (Leeper et al., 2020).

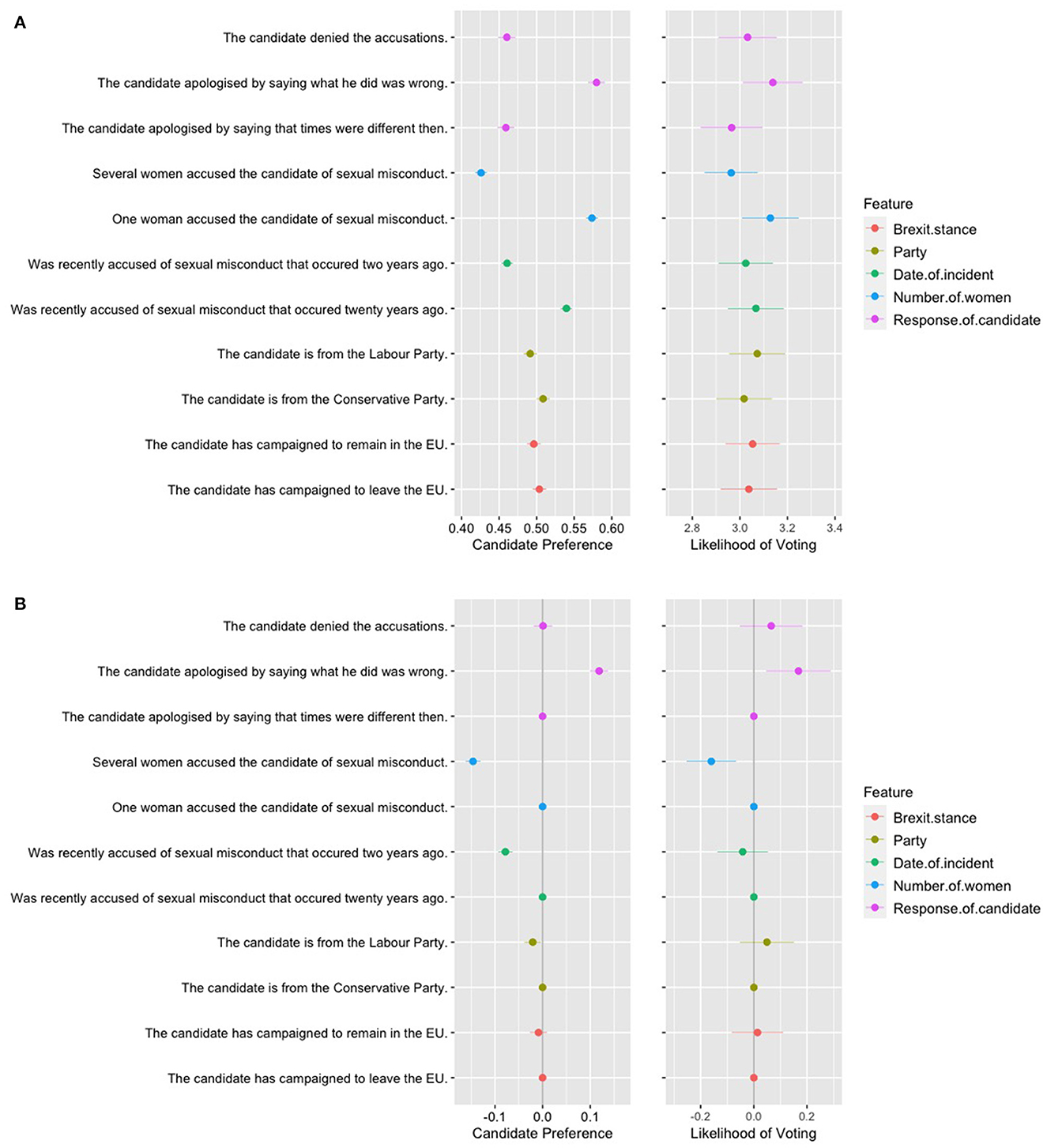

Figure 1A shows the average marginal component effects of all respondents, with each point representing. The left-hand graph, shows the results of the binary choice question, “Which of the two candidates would you prefer to see elected?”, and the right-hand graph shows the results of the questions ‘on a scale of 1 to 10, where 1 indicates “not at all likely”, and 10 indicates “very likely”, what is your likelihood for voting for candidate 1?', with a second identical question asking about candidate 2. The point estimates show the impact of the effect of each value, relative to the baseline category, with a confidence interval of 95 per cent. The baseline comparison point estimates (One woman, Occurred 20 years ago, Apologized – different times, Campaigned to leave, Conservative party candidate) have no confidence interval and are controlled at zero as a comparison for each attribute.

Figure 1. (A) Average marginal component effect of sexual harassment accusation of all respondents. Point estimates are ACME, the average change in the predicted outcome (e.g., likelihood of choosing a candidate, likelihood of voting) associated with a one-unit change in a specific attribute or feature of a product or candidate, holding all other attributes constant (n = 1750). (B) Marginal Means - Effect of Sexual Harassment accusation of all respondents. Point estimates are marginal means representing the mean outcome across all appearances of a particular conjoint feature level, averaging across all other features. The estimates on the left are based on a discrete choice preference between two candidate profiles and the estimates on the right are ranked preferences of each candidate, across 5 tasks (n = 1750).

Consistent with our expectations, the severity of the accusations makes a significant difference to evaluations. The “candidate preference” graph, starting with the “number of women”, shows that candidates with accusations by “several women” are rated much lower than those with accusations by one woman (baseline), fitting with expectations. Perhaps this is unsurprising, given that several women making accusations' gives them more weight and is also a strong signal about the “poor” character of the accused. For the “likelihood of voting” graph, the result is similar, with accusations by “several women” negatively affecting the respondents vote choice, in comparison to the baseline. Whilst the confidence interval is large for “likelihood of voting”, it is entirely under the baseline, showing a fully negative effect.

Consistent with our hypothesized effects, both graphs in Figure 1A show on average that incidents which happened 2 years ago impact respondents more negatively than the baseline response of a more historic event of “20 years ago”. “Candidate preference” shows that incidents said to occur 2 years ago are more negative (–0.07) than the baseline response of “20 years ago”. However, for the “likelihood of voting” graph, the result for “2 years ago” (−0.04) does cross the baseline, giving us the chance that the “20 years ago” response could potentially be more positive when judged on a rating scale. This is also true of the ‘likelihood of voting' data, where events “2 years ago” are again, viewed more negatively (−0.04) than “20 years ago” on the baseline. However, with the “likelihood of voting” graph, the confidence interval is wide, crossing the baseline, meaning that like the “number of women”, this result is not statistically significant.

However, there are some notable results where our hypotheses are not supported. First, contrary to impression management expectations denials are not more successful in mitigating any negative electoral consequences. Those who apologized and declared they were wrong had greater support both in terms of discrete choice and likelihood to vote. Furthermore, the type of apology mattered. Those who apologized and indicated that times were different where no more successful in mitigating the negative consequences of the allegations than those who denied them. Second, Remain supporters were no more likely to be punished that Leave supporters indicating that there is no strong indication of a negative impact of norm violation. This is not a direct test of the motivated reasoning hypothesis, but we return to a discussion of how gender attitudes can moderate political affiliations such as Brexit support and partisanship.

Figure 1B shows reports the marginal means for the same analysis. The results are similar to the AMCE results in that the more severe allegations and more recent allegations, reduce support for the candidate. Given we have estimates of mean support even for baseline comparisons we can see those who denied allegations or apologized saying times were difference are equally punished relative to an apology where the is an admission of guilt. It is important to recognize that in modeling the likelihood of voting for each of the accused candidate, i.e., the ranking of each candidate profile, the marginal mean does not pass the 0.50 threshold or the midpoint of the scale. Thus, in the experiment, there is overall a very low likelihood of voting for candidates who have been accused of any sexual misconduct and we view the forced choice between the two profiles is really a choice between two candidates where there is a low likelihood of voting for either.

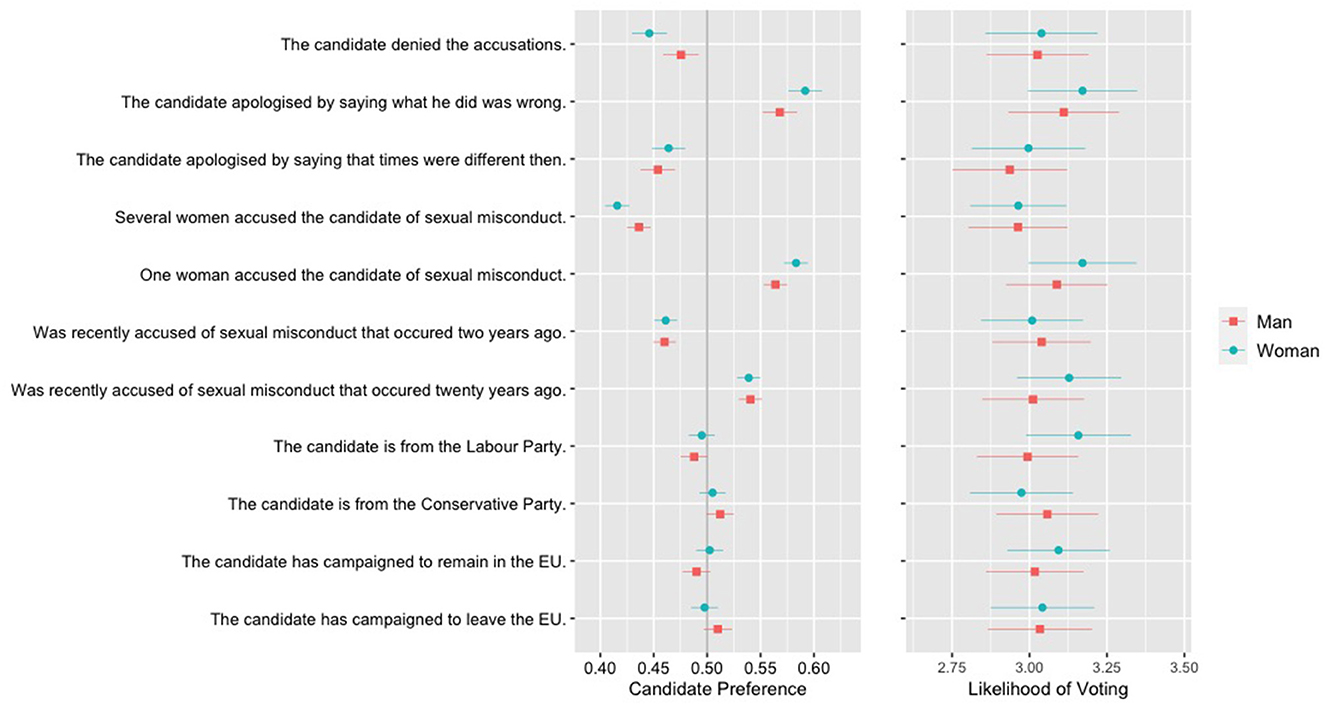

We next move to our subgroup analysis. Figure 2 shows the marginal mean estimates from the conjoint analysis, subset by respondent gender (H1). The left-hand graph, shows the results of the binary choice question, “Which of the two candidates would you prefer to see elected?”, and the right-hand graph shows the results of the questions “on a scale of 1 to 10, where 1 indicates ‘not at all likely', and 10 indicates ‘very likely', what is your likelihood for voting for candidate 1?”, with a second identical question asking about candidate 2. The two points, are shown in blue for women and red for men. To summarize the hypothesized expectations, women who are more likely to have great personal experiences of sexual misconduct or feel more threatened, are more likely to be impacted by the attributes about the severity and recency of the accusations. Multiple allegations increase the chance that the allegations are true and hence they may be more sensitive to these accusations. We also hypothesize that they also are more negatively impacted by attempts by the candidate to manage impression through the denial of accusations.

Figure 2. Marginal means impact of gender identity on accusation of sexual misconduct. Point estimates are marginal means representing the mean outcome across all appearances of a particular conjoint feature level, averaging across all other features. The estimates on the left are based on a discrete choice preference between two candidate profiles and the estimates on the right are ranked preferences of each candidate, across 5 tasks (n = 1750).

Consistent with our expectations, in terms of “candidate preference”, accusations by “several women” have a more negative impact for women than men. However, these same differences are not evident for the recency of the event. Contrary to expectations women are not more sensitive to recency of the event or the candidate's response. Men and women are equally likely to hold politicians accountable (punish) for allegations from 2 years ago and, even though women have a lower level of mean support than men for those who denied the allegations, these are not statistically significant differences. The subgroup differences in rating the likelihood of voting for each accused candidate shows very similar results for both men and women. As in Figure 1B, the lack of statistically significant differences between subgroups also reflects that there is a low level of support among all respondents with little variation.

Figure 3 tests for subgroup differences among polarized gender identities (H2). We expected that those with hypermasculine and to a lesser extent, hyperfeminine identities would be less impacted by the accusations. We find some limited evidence in that those with weak feminine identities are more negatively impacted by the candidate denying the accusations. However, there are no significant differences across the number of women making the accusations or the timing of the events. We do, on the other hand, see evidence of differences on the political characteristics of the candidates. Hyperfeminine and hypermasculine are resistant to the negative consequences of accusations for Conservative party candidates for those who have campaigned to leave the EU. Those with weak feminine identities are more positive about Labor party candidates and those who campaigned to remain in the EU. Thus, we see some differentiation among the types of attributes and how they are moderated by gender attitudes. Polarized gender identities are conditioning the political attributes of the candidates rather than the attributes of the sexual misconduct itself in terms of preferred candidates. We come back to this point in the discussion to consider the links between polarized gender identities in the context of partisan motivated reasoning.

Figure 3. Marginal means impact of polarized gender identities on accusation of sexual misconduct, subset by levels of feminine and masculine identities. Point estimates are marginal means representing the mean outcome across all appearances of a particular conjoint feature level, averaging across all other features. The estimates on the left are based on a discrete choice preference between two candidate profiles and the estimates on the right are ranked preferences of each candidate, across 5 tasks (n = 1750).

The marginal means for the likelihood of voting for each accused candidates are displayed in the lower panel of Figure 3. The results displayed here are the opposite of what we expected. Those with more polarized gender identities are less likely to vote for each candidate regardless of political attributes or the attributes of the accusations. Those with weak identities have higher rankings than those with polarized identities but lower than those that we have labeled as having undifferentiated identities. This is completely unexpected where even for the political attributes we see the same differences among the categories of gender identities. We discuss in the conclusions how this may possibly reflect negative attitudes about all candidates among those who polarized identities.

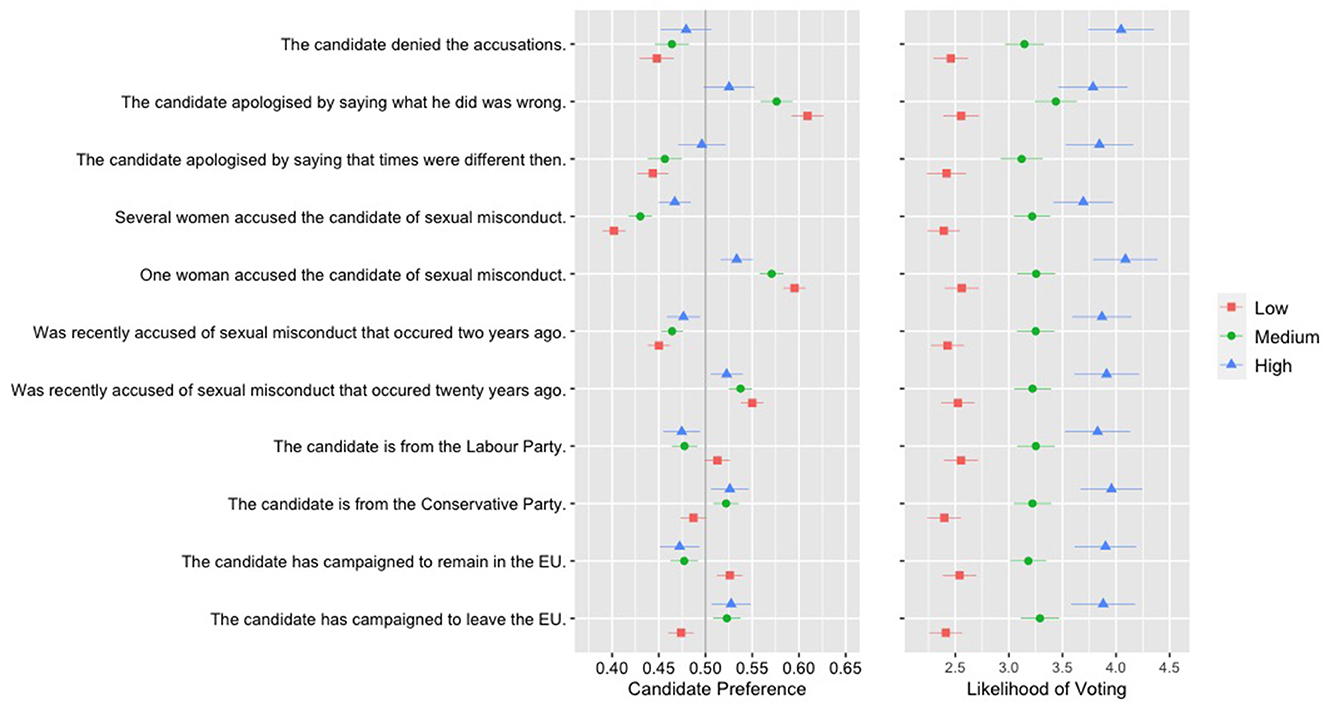

Finally, Figure 4 shows the results from the test of subgroup differences by hostile sexist attitudes (H3). Unlike gender identities, we do note difference here with, in general, those holding sexist attitudes being less likely to be impacted by the accusations. For candidate preferences (the left panel), those with low levels of hostile sexism prefer candidates who have apologized and said what they did was wrong whereas those who have scored high on the hostile sexism index prefer those who have apologized by saying times were different. For those low on hostile sexism there are no differences though between denying and apologizing with times were different. Interestingly, the baseline effects in Figure 1 showed that apologies and accepting responsibility were more effective in maintaining support than denials and this was counter to expectations from impression management theory. However, in the discrete choice results in Figure 4 we see that this apology is less effective among those with hostile sexist attitudes. Therefore, impression management may only be effective for those high on hostile sexism because the impression being managed is more consistent with patriarchal views.

Figure 4. Marginal Means Impact of Accusation of Sexual Misconduct on Candidate Preferences, subset by levels of hostile sexism. Point estimates are marginal means representing the mean outcome across all appearances of a particular conjoint feature level, averaging across all other features. The estimates on the left are based on a discrete choice preference between two candidate profiles and the estimates on the right are ranked preferences of each candidate, across 5 tasks (n = 1750).

Sexist attitudes also significantly moderate the severity and recency of the accusations. For example, for those who are high on hostile sexism the number of women making the accusations makes less difference to preferences than for those low on sexism. Those who are low on sexism have a much higher preference for those candidates who were accused of sexual misconduct by one woman. A similar pattern is evident for the when the incidents happened. The timing of the event does not distinguish preferences as strongly for those with high levels of hostile sexism whereas for low hostile sexists the date of occurrence has a stronger relationship to preferences. Again, these results indicate sexist attitudes moderate preference choices across severity, recency, and candidate response.

The impact of the political attributes of the candidates, their partisanship and Brexit position, are to some extent moderated by sexist attitudes. Those with low levels of sexism, relative to those in the mid and high categories of hostile sexism, are less likely to prefer the candidates from the Conservative party and those who campaigned to remain.

The pattern for the moderating impact of sexism on the likelihood of voting for each candidate is similar to the other models tested rankings of candidates in that the attributes are not conditioned by the gender attitude. However, the pattern is dissimilar in that sexist attitudes impact where respondents will vote for a candidate accused of sexual misconduct in general. Those who score high are the hostile sexism scale are more immune to the allegations than are those who are in the middle of the scale and much more than those who score lowest on the hostile sexism scale. Those respondents lowest on the hostile sexism scale have the lowest mean probability of voting for each candidate accused of sexual misconduct regardless of the attributes of the candidate or the scandal. This demonstrates that hostile sexism lessens the ability of candidates accused of sexual misconduct to be held accountable.

6. Conclusions

The ability to maintain accountability is central to democratic legitimacy. Drawing on the strength of conjoint experiments we examined five attributes of sexual misconduct scandals about the political dispositions of the candidates and the characteristics of the scandal itself – to examine how these impact voters' willingness to hold politicians accountable. Work on political scandals have found that partisan motivated reasoning might provide a limitation to whether voters hold politicians accountable. Our main focus in the conjoint experiment is to examine whether negative attitudes about women can moderate the ability of citizens to hold politicians accountable for behavior that is damaging to women. We recognize that men are also the victims of misconduct but in this study we have limited our analysis to perpetrators who are men and vitcims who are women.

Overall, the results of our conjoint analysis are consistent with other experiments looking at similar questions in that we find the severity of the allegations matters – more victims increase willingness to punish. Apologies matter but contrary to expectations from impression management apologies and accepting behavior was wrong increases preferences for a candidate relative to denial of the accusations. Generally, we find also, and this is contrary to studies that examine other types of scandals, that apologies make a difference. It does not seem to be an effective strategy for politicians to deny the allegations. Perhaps our results here – that accepting blame for doing something wrong – reflects the impact of the #MeToo movement on how people consider these allegations when calculating voting decisions (at least under hypothetical and experimental conditions). In terms of accountability, this finding suggests that while variations in the type of allegation can be a signal about poor character, apologizing and admitting to wrongdoing can also be a strong positive signal about character.

The answer to the question on whether the electoral consequences of sexual misconduct scandals are moderated by gender attitudes is that it depends, the type of gender attitude and the attribute. Hostile sexism was a strong moderator of attributes. Largely, those high on hostile sexism were more immune to the attributes of the scandal than those who were low on hostile sexism. These findings reflect the growing body of evidence that sexism can be a foundational attitude in the dynamics of political preferences. Similar to studies that have found sexism to drive US presidential choice (Ratliff et al., 2019) and partisan preferences in Britain (de Geus et al., 2022). It is also important to reiterate the point that those who would hold hostile sexist attitudes were less likely to punish candidates in general. That we find these strong effects for sexism and no moderating impact of gender identity suggests negative attitudes about women rather than the attitudes of women are more salient in explaining resistance to holding politicians accountable in the #MeToo era.

Finally, it is important to recognize where the type of attribute did make a difference to whether gender attitudes moderated the impact of the sexual misconduct. For the most part of the bidimensional measure of feminine and masculine identity did not moderate the impact of the scandal except when it came to the political attributes of the candidates. Those with more polarized, sex typical identities (i.e., hypermasculine and hyperfeminine) were less likely to punish Conservative and Leave supporting candidates. Thus, we see how acceptance of sexual misconduct can be tolerated for politicians who hold right wing views or are consistent with a strong state – views that would be consistent with defending a traditional patriarchal society. Without the use of the bidimensional scale we would have concluded that gender identity has no moderating impact as there were no significant differences using the categorical measure of gender identity. Given that polarized gender identities can prevent the exercise of electoral accountability to further maintain patriarchal norms in politics, further studies on sexual misconduct scandals specifically and other political policies that challenge traditional gender roles should incorporate this bidimensional measure of gender identities.

Data availability statement

The raw data supporting the conclusions of this article will be made available by the authors, upon request, without undue reservation.

Ethics statement

The studies involving human participants were reviewed and approved by the University of Exeter, Social Sciences, and International Studies. The patients/participants provided their written informed consent to participate in this study.

Author contributions

BL contributed to research design, analysis, and writing. SB contributed equally to design, analysis, and writing. All authors contributed to the article and approved the submitted version.

Funding

This work was funded by the European Union (ERC Advanced Grant, TWICEASGOOD, 101019284).

Conflict of interest

The authors declare that the research was conducted in the absence of any commercial or financial relationships that could be construed as a potential conflict of interest.

Publisher's note

All claims expressed in this article are solely those of the authors and do not necessarily represent those of their affiliated organizations, or those of the publisher, the editors and the reviewers. Any product that may be evaluated in this article, or claim that may be made by its manufacturer, is not guaranteed or endorsed by the publisher.

Footnotes

1. ^After missing data from non-response on items has been removed our sample size is reduced to 1750.

2. ^The response categories are: “man”, “woman”, “transgender” and “Do not identify as male, female or transgender”. This question does not allow for an expression of identity outside these categories which does not reflect a more inclusive measure. There were 19 missing responses on the gender identity question which is similar to the missing cases on region. Thus, we are confident non-response on this item does not introduce bias. We rely on the femininity and masculinity scale to capture fluidity of gender because 10 respondents (0.5% of sample) identified as transgender or non-binary. These latter respondents also were missing on some tasks for the conjoint experiment and had to be dropped from the analysis.

3. ^Gidengil and Stolle (2021) use the most extreme categories on the scale for their hyperfeminine and hyper masculine categories and have a category of strong identity. We have collapsed their strong and weak into a single category of weak. They have another mid-category of androgynous to reflect those who put themselves above the midpoint on both scales. However, we have placed this in the undifferentiated category to simply the subgroup analysis for the conjoint experiments. Our distributions are roughly are similar to those reported in Table 1 of their study.

4. ^Those who responded “Don't Know” have been dropped from the analysis.

References

Archer, A. M., and Kam, C. D. (2020). Modern sexism in modern times public opinion in the #metoo era. Public Opinion Q. 84, 813–837. doi: 10.1093/poq/nfaa058

Banducci, S. A., and Karp, J. A. (1994). Electoral consequences of scandal and reapportionment. in the 1992 House elections. Am. Polit. Q. 22, 3–26. doi: 10.1177/1532673X9402200101

Barnes, T. D., Beaulieu, E., and Saxton, G. W. (2020). Sex and corruption: how sexism shapes voters' responses to scandal. Politics Groups Ident. 8, 103–121. doi: 10.1080/21565503.2018.1441725

Barreto, M., and Doyle, D. M. (2022). Benevolent and hostile sexism in a shifting global context. Nat. Rev. Psychol. 2, 98–111.

Batty, D. (2019). More than half of UK students say they have faced unwanted sexual behaviour. The Guardian. Available online at: https://www.theguardian.com/education/2019/feb/26/more-than-half-of-uk-students-say-they-have-faced-unwanted-sexual-behaviour

Bowler, S., and Karp, J. A. (2004). Politicians, scandals, and trust in government. Political Behav. 26, 271–287. doi: 10.1023/B:POBE.0000043456.87303.3a

Brandes, E. (2021). ‘To Believe or Not to Believe: Voters' Responses to Sexual Assault Allegations in Politics'. Bucknell University. Available online at: https://digitalcommons.bucknell.edu/honors_theses/574 (accessed March 15 2022).

Collignon, S., and Savani, M. M. (2023). Values and candidate evaluation: How voters respond to allegations of sexual harassment. Elect. Stud. 83, 102613. doi: 10.1016/j.electstud.2023.102613

Costa, M., Briggs, T., Chahal, A., Fried, J., Garg, R., Kriz, S., et al. (2020). How partisanship and sexism influence voters' reactions to political #MeToo scandals. Res. Polit. 7, 2053168020941727. doi: 10.1177/2053168020941727

Craig, S. C., and Cossette, P. S. (2022). Eye of the beholder: Partisanship, identity, and the politics of sexual harassment. Polit. Behav. 44, 749–777. doi: 10.1007/s11109-020-09631-4

Criado-Perez, C. (2019). Invisible Women: Exposing Data Bias in a World Made for Men. London: Chatto & Windus.

de Geus, R., Ralph-Morrow, E., and Shorrocks, R. (2022). Understanding ambivalent sexism and its relationship with electoral choice in Britain. Br. J. Polit. Sci. 52, 1564–1583.

Doherty, D., Dowling, C. M., and Miller, M. G. (2014). Does time heal all wounds? Sex scandals, tax evasion, and the passage of time. Polit. Sci. Polit. 47, 357–366. doi: 10.1017/S1049096514000213

Duncan, P., and Topping, A. (2018). Men underestimate levels of sexual harassment against women–Survey. The Guardian. p. 6.

Dunin-Wasowicz, R. (2018). The Brexit Vote has Only Deepened the Political and Social Divisions Within British Society. Available online at: https://blogs.lse.ac.uk/brexit/2018/02/01/the-brexit-vote-has-only-deepened-the-political-and-social-divisions-within-british-society/

Fawcett Society. (2018, October 2). “#METOO ONE YEAR ON - WHAT'S CHANGED?”. Fawcett Society. Available online at: https://www.fawcettsociety.org.uk/metoo-one-year (accessed April 30, 2020).

Frazier, S., and Kreutz, C. (2019). How Constituents React to Allegations of Sexual Misconduct in the “Me Too” Era. Sigma: J. Polit. Int. Stud. 36, 50–62.

Gidengil, E., and Stolle, D. (2021). Beyond the gender gap: the role of gender identity. J. Polit. 83, 1818–1822. doi: 10.1086/711406

Glick, P., and Fiske, S. (1996). The ambivalent sexism inventory: Differentiating hostile and benevolent sexism. J. Pers. Soc. Psychol. 70, 491–512. doi: 10.1037/0022-3514.70.3.491

Glick, P., and Fiske, S. T. (2001). An ambivalent alliance: Hostile and benevolent sexism as complementary justifications for gender inequality. Am. Psychol. 56, 109. doi: 10.1037/0003-066X.56.2.109

Green, J., and Shorrocks, R. (2023). The gender backlash in the vote for brexit. Polit. Behav. 45, 347–371.

Hainmueller, J., Hopkins, D., and Yamamoto, T. (2014). 22 political analysis cjoint: causal inference in conjoint analysis: understanding multi-dimensional choices via stated preference experiments. Polit. Sci. 22, 1–30. doi: 10.2139/ssrn.2231687

Hobolt, S. B., Leeper, T. J., and Tilley, J. (2018). Emerging Brexit Identities. Available online at: https://ukandeu.ac.uk/emerging-brexit-identities/

Hobolt, S. B., Leeper, T. J., and Tilley, J. (2021). Divided by the vote: Affective polarization in the wake of the Brexit referendum. Br. J. Polit. Sci. 51, 1476–1493. doi: 10.1017/S0007123420000125

Holman, M. R., and Kalmoe, N. P. (2021). Partisanship in the #MeToo era. Persp. Polit. 29, 1–18. doi: 10.1017/S1537592721001912

Jost, J. T. (2019). A quarter century of system justification theory: Questions, answers, criticisms, and societal applications. Br. J. Soc. Psychol. 58, 263–314. doi: 10.1111/bjso.12297

Kirkland, P. A., and Coppock, A. (2018). Candidate choice without party labels: new insights from conjoint survey experiments. Polit. Behav. 40, 571–591. doi: 10.1007/s11109-017-9414-8

Klar, S., and McCoy, A. (2021a). Partisan-motivated evaluations of sexual misconduct and the mitigating role of the # MeToo movement. Am. J. Polit. Sci. 65, 777–789. doi: 10.1111/ajps.12619

Klar, S., and McCoy, A. (2021b). The #MeToo movement and attitudes toward President Trump in the wake of a sexual misconduct allegation. Polit. Groups Ident. 10, 837–846. doi: 10.1080/21565503.2021.1908374

Kunda, Z. (1990). The case for motivated reasoning. Psychol. Bullet. 108, 480. doi: 10.1037/0033-2909.108.3.480

Kunst, J. R., Bailey, A., Prendergast, C., and Gundersen, A. (2019). Sexism, rape myths and feminist identification explain gender differences in attitudes toward the #metoo social media campaign in two countries. Media Psychol. 22, 818–843. doi: 10.1080/15213269.2018.1532300

Lawless, J. L., and Fox, R. L. (2018). A trump effect? Women and the 2018 midterm elections. The Forum. 16, 665–686.

Leeper, T. J., Hobolt, S. B., and Tilley, J. (2020). Measuring subgroup preferences in conjoint experiments. Polit. Anal. 28, 207–221. doi: 10.1017/pan.2019.30

Lewinsky, M. (2018). ‘Emerging from “the House of Gaslight” in the Age of #MeToo'. Vanity Fair. Available online at: https://www.vanityfair.com/news/2018/02/monica-lewinsky-in-the-age-of-metoo (accessed June 27, 2022).

Maier, J. (2011). The impact of political scandals on political support: an experimental test of two theories. Int. Polit. Sci. Rev. 32, 283–302. doi: 10.1177/0192512110378056

Mastari, L., Spruyt, B., and Siongers, J. (2019). Benevolent and hostile sexism in social spheres: the impact of parents, school and romance on Belgian adolescents' sexist attitudes. Front. Sociol. 4, 47. doi: 10.3389/fsoc.2019.00047

Masuoka, N., Grose, C., and Junn, J. (2021). Sexual harassment and candidate evaluation: Gender and partisanship interact to affect voter responses to candidates accused of harassment. Polit. Behav. 6, 1–23. doi: 10.1007/s11109-021-09761-3

Matthews, H. (2019). Biden's Status as Democratic Front-Runner Reveals #MeToo as Weak Political Strategy. Available online at: https://theconversation.com/bidens-status-as-democratic-front-runner-reveals-metoo-as-weak-political-strategy-114813

McAndrews, J. R., de Geus, R., and Loewen, P. J. (2019). Voters Punish Politicians for Credible Allegations of Sexual Misconduct.

Ortiz, R. R., and Smith, A. M. (2022). A social identity threat perspective on why partisans may engage in greater victim blaming and sexual assault myth acceptance in the #MeToo era. Viol. Against Women 28, 1302–1325. doi: 10.1177/10778012211014554

Pellegrini, A. (2018). #MeToo: Before and after. Stu. Gender Sexuality 19, 262–264. doi: 10.1080/15240657.2018.1531530

Ratliff, K. A., Redford, L., Conway, J., and Tucker Smith, C. (2019). Engendering support: Hostile sexism predicts voting for Donald Trump over Hillary Clinton in the 2016 U.S. presidential election. Group Process. Intergroup Relat. 22, 578–593.

Rosewarne, L. (2019). # MeToo and the Reasons to be Cautious. #MeToo and the Politics of Social Change. Cham: Springer International Publishing, 171–84.

Rotundo, M., Nguyen, D. -H., and Sackett, P. R. (2001). A meta-analytic review of gender differences in perceptions of sexual harassment. J. Appl. Psychol. 86, 914–922.

Russell, B. L., and Trigg, K. Y. (2004). Tolerance of sexual harassment: An examination of gender differences, ambivalent sexism, social dominance, and gender roles. Sex Roles. 50, 565–573. doi: 10.1023/B:SERS.0000023075.32252.fd

Sarmiento-Mirwaldt, K., Allen, N., and Birch, S. (2014). No sex scandals please, we're French: french attitudes towards politicians' public and private conduct. West Eur. Politics 37, 867–885. doi: 10.1080/01402382.2014.911482

Schaffner, B. F., MacWilliams, M., and Nteta, T. (2018). Explaining white polarization in the 2016 vote for president: The sobering role of racism and sexism. Polit. Sci. Q. 133, 9–34.

Schermerhorn, N., and Vescio, T. K. (2022). Men's and women's endorsement of hegemonic masculinity and responses to COVID-19. J. Health Psychol. 28, 251–266.

Schlenker, B. R. (1980). Impression Management: The Self-Concept, Social Identity, and Interpersonal Relations. Monterey, Calif: Brooks/Cole Pub. Co.

Schwarz, S., Baum, M. A., and Cohen, D. K. (2020). (Sex) crime and punishment in the #MeToo era: how the public views rape. Polit. Behav. 44, 75–104. doi: 10.1007/s11109-020-09610-9

Sigal, J., Hsu, L., Foodim, S., and Betman, J. (1988). Factors affecting perceptions of political candidates accused of sexual and financial misconduct. Polit. Psychol. 9, 273–280. doi: 10.2307/3790956

Smith, J. (2019). ‘Donald Trump and Boris Johnson Are Liked Because They Can Get Away With Anything—Moralizing Won't Stop Them | Opinion'. Newsweek. Available online at: https://www.newsweek.com/trump-johnson-populism-what-they-want-1450951 (accessed October 8 2022).

Sobolewska, M., Ford, R. A., and Goodwin, M. J. (2019). The Brexit Referendum And Identity Politics in Britain: Social Cleavages, Party Competition, and the Future of Immigration and Integration Policy. Available online at: https://gtr.ukri.org/projects?ref.ES%2FR000522%2F1

Stark, S., and Collignon, S. (2022). Sexual predators in contest for public office: How the american electorate responds to news of allegations of candidates committing sexual assault and harassment. Polit. Stud. Assoc. 20, 329–352.

Szekeres, H., Shuman, E., and Saguy, T. (2020). Views of sexual assault following #MeToo: the role of gender and individual differences. Person. Ind. Diff. 166, 110203. doi: 10.1016/j.paid.2020.110203

UK Parliament. (2018). Sexual Harassment in the Workplace. London: House of Commons Women and Equalities Committee.

Vonnahme, B. M. (2014). Surviving scandal: An exploration of the immediate and lasting effects of scandal on candidate evaluation. Soc. Sci. Q. 95, 1308–1321. doi: 10.1111/ssqu.12073

Wängnerud, L., Solevid, M., and Djerf-Pierre, M. (2019). Moving beyond categorical gender in studies of risk aversion and anxiety. Polit. Gender 15, 826–850. doi: 10.1017/S1743923X18000648

YouGov. (2019). Only 55% of Britons Have Heard of #MeToo. Available online at: https://yougov.co.uk/topics/politics/articles-reports/2019/03/07/only-55-britons-have-heard-metoo

Keywords: conjoint experiment, elections, sexual misconduct, candidate evaluations, sexism, gender identity

Citation: Longdon B and Banducci S (2023) The role of sexism in holding politicians accountable for sexual misconduct. Front. Polit. Sci. 5:1064902. doi: 10.3389/fpos.2023.1064902

Received: 08 October 2022; Accepted: 01 June 2023;

Published: 15 August 2023.

Edited by:

Jorge M. Fernandes, University of Lisbon, PortugalReviewed by:

Elizabeth J. Zechmeister, Vanderbilt University, United StatesJill Sheppard, Australian National University, Australia

Copyright © 2023 Longdon and Banducci. This is an open-access article distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution License (CC BY). The use, distribution or reproduction in other forums is permitted, provided the original author(s) and the copyright owner(s) are credited and that the original publication in this journal is cited, in accordance with accepted academic practice. No use, distribution or reproduction is permitted which does not comply with these terms.

*Correspondence: Susan Banducci, s.a.banducci@exeter.ac.uk

Bella Longdon

Bella Longdon Susan Banducci

Susan Banducci