- 1Department of Neurology, Tokai University School of Medicine, Isehara, Japan

- 2Department of Legal Medicine, St. Marianna University School of Medicine, Kawasaki, Japan

- 3Support Center for Medical Research and Education, Tokai University, Isehara, Japan

- 4Department of Clinical Laboratory, National Center of Neurology and Psychiatry, National Center Hospital, Tokyo, Japan

- 5Department of Neurology, Mihara Memorial Hospital, Isesaki, Japan

- 6Department of Neuropathology, Tokyo Metropolitan Geriatric Hospital and Institute of Gerontology, Tokyo, Japan

- 7Department of Pathology, Brain Research Institute, Niigata University, Niigata, Japan

Background: Amyotrophic lateral sclerosis (ALS) is a fatal neurodegenerative disorder associated with progressive impairment of spinal motor neurons. Continuous research endeavor is underway to fully understand the molecular mechanisms associating with this disorder. Although several studies have implied the involvement of inositol pyrophosphate IP7 in ALS, there is no direct experimental evidence proving this notion. In this study, we analyzed inositol pyrophosphate IP7 and its precursor IP6 in the mouse and human ALS biological samples to directly assess whether IP7 level and/or its metabolism are altered in ALS disease state.

Methods: We used a liquid chromatography-mass spectrometry (LC-MS) protocol originally-designed for mammalian IP6 and IP7 analysis. We measured the abundance of these molecules in the central nervous system (CNS) of ALS mouse model SOD1(G93A) transgenic (TG) mice as well as postmortem spinal cord of ALS patients. Cerebrospinal fluid (CSF) and peripheral blood mononuclear cells (PBMCs) from ALS patients were also analyzed to assess if IP7 status in these biofluids is associated with ALS disease state.

Results: SOD1(G93A) TG mice showed significant increase of IP7 level in the spinal cord compared with control mice at the late stage of disease progression, while its level in cerebrum and cerebellum remains constant. We also observed significantly elevated IP7 level and its product-to-precursor ratio (IP7/IP6) in the postmortem spinal cord of ALS patients, suggesting enhanced enzymatic activity of IP7-synthesizing kinases in the human ALS spinal cord. In contrast, human CSF did not contain detectable level of IP6 and IP7, and neither the IP7 level nor the IP7/IP6 ratio in human PBMCs differentiated ALS patients from age-matched healthy individuals.

Conclusion: By directly analyzing IP7 in the CNS of ALS mice and humans, the findings of this study provide direct evidence that IP7 level and/or the enzymatic activity of IP7-generating kinases IP6Ks are elevated in ALS spinal cord. On the other hand, this study also showed that IP7 is not suitable for biofluid-based ALS diagnosis. Further investigation is required to elucidate a role of IP7 in ALS pathology and utilize IP7 metabolism on the diagnostic application of ALS.

1 Introduction

Amyotrophic lateral sclerosis (ALS) is an incurable neurodegenerative disorder categorized to the progressive motor neuron disease, and its incident is most frequent in sexagenarians and septuagenarians (1, 2). An epidemiological study showed that 1.68 per 100,000 person-years suffered from this disease in worldwide with substantial variations in region (3). Sporadic ALS where the ALS onset is independently of hereditary traits accounts for 70–80% of all of the ALS cases, confounding the genetic prediction of future ALS onset (4). Due to the absence of effective biomarkers for ALS, its diagnosis hinges on the indirect approaches by checking clinical symptoms and measuring muscle action potential amplitudes, which results in the delayed therapeutic intervention with limited number of medical options (5). To tackle these issues, a number of ALS-causative proteins including C9orf72, TDP-43 and FUS have been identified and studied for the development of ALS therapeutic agents selectively targeting these molecules (6, 7). In addition, the discovery of potentially diagnostic biomarkers for ALS such as Neurofilament L (NfL) facilitates the biofluid-based noninvasive approaches for ALS diagnosis (8–10). Yet, there is still a lack of molecular information with regard to the ALS pathology, and thus its features in molecular machinery should be elucidated more clearly for liberating humanity from the agony of this disease.

Inositol pyrophosphate exists in a wide variety of organisms from slime molds and fungi to mammals and is involved in numerous cellular processes including intracellular signaling (11–13). Diphosphoinositol pentakisphosphate (a.k.a. IP7), a representative inositol pyrophosphate in mammals, is synthesized from the precursor molecule inositol hexakisphosphate (a.k.a. IP6) by inositol hexakisphosphate kinases (IP6Ks). So far, several lines of evidence suggested pathological roles of IP6Ks and IP7 in stress response and neurodegeneration. IP6K2, one of the major IP7-synthesizing kinase in mammals, was characterized as a cell death mediator (14) and IP7 facilitates cellular apoptosis by reactive oxygen treatment (15). Considering our previous observations of IP6K2 mRNA induction during presymptomatic disease state of ALS (16) and IP6K2 modulatory role in TDP-43-mediated cellular apoptosis (17), these facts collectively imply the notion that IP7 would be induced in aberrant motor neuron of ALS disease state. However, none of the direct evidences has not been obtained due to lack of technologies directly detecting and quantifying IP7. Recently, we developed an analytical protocol directly and selectively detecting IP7 in mammalian tissues (18, 19), unlocking the direct evaluation of this molecule in various clinical biopsies.

In this study, we analyzed endogenous IP7 and its precursor IP6 in ALS model mice as well as human ALS patients by an originally-designed liquid chromatography mass spectrometry (LC-MS) protocol and assessed if ALS disease state would be accompanied by altered IP7 level.

2 Materials and methods

2.1 Human samples and peripheral blood cell fractionation

Frozen postmortem spinal cords derived from 9 ALS patients and five neurologically normal patients were obtained from Japan Brain Bank Net (JBBN) and Brain Research Institute of Niigata University. Each 3 mL of cerebrospinal fluid (CSF) was collected from 3 ALS patients by lumber puncture. Peripheral blood samples (20 mL) were collected from 25 ALS patients after the definitive diagnosis by the El Escorial diagnostic criteria (20) and 22 age-matched healthy controls in our hospital (Supplementary Tables 1, 2). Three out of 25 ALS patients were excluded as statistical outliers, and therefore 22 ALS patients were used for the subsequent analysis. After the isolation using a Lymphocyte Separation Solution (Nacalai Tesque, Japan), peripheral blood mononuclear cells (PBMCs) were lysed by Lysis buffer (0.01% Triton X-100, 1 mM EDTA, 20 mM Tris-HCl). After centrifugation, the supernatant was further processed to isolate IP6 and IP7 for the subsequent LC-MS analysis. All participants before passing away or their families provided written informed consent. Experiments using human samples were performed with institutional approval and guidelines from the Clinical Investigation Committee at Tokai University School of Medicine (institutional review board No. 10R-010).

2.2 Mouse samples

All experiments involving animals were performed in accordance with protocols approved by institutional animal care guidelines (Tokai University School of Medicine). SOD1(G93A) transgenic (TG) mice and littermate wild-type (WT) mice were obtained from Clea Japan (Tokyo, Japan) and maintained at an ambient temperature of 23 ± 2°C and humidity of 55 ± 15% with a 12 h light-dark cycle. Food (CE-2; Clea Japan) and water were fed ad libitum. The behavioral performance of the TG mice was regularly monitored by rotarod test. These mice were anesthetized using isoflurane and then sacrificed to collect the central nervous system (CNS; cerebrum, cerebellum, spinal cord). The harvested organs were frozen until further use.

2.3 Extraction of IP6 and IP7 from human and mouse samples

Human and mouse frozen tissues were homogenized using a Shake Master Neo (Bio Medical Science). The crude lysates were centrifuged to collect the supernatants. The supernatants from tissues and cells were mixed with an equal volume of 2 M perchloric acid and further centrifuged to remove insoluble protein fraction. After adding 3 nmol of hexadeutero-myo-inositol trispyrophosphate (ITPP-d6, Toronto Research Chemicals) as a surrogate internal standard, IP6 and IP7 were purified using titanium dioxide beads (GL Sciences) as described previously (21).

2.4 Measurements of IP6 and IP7 by liquid chromatography–tandem mass spectrometry (LC-MS)

Quantitative measurement of IP6 and IP7 in human and mouse samples were performed using an originally-designed LC-MS protocol (18, 19). Briefly, chromatographic separation of IP6, IP7, and internal standard ITPP-d6 is achieved by hydrophilic interaction liquid chromatography (HILIC) mode with a polymer-based bioinert column (HILICpak VG-50 2D; Shodex, Tokyo, Japan). The aqueous mobile phase was 300 mM ammonium bicarbonate buffer (pH 10.5) containing 0.1% InfinityLab deactivator additive (Agilent Technologies) and the organic mobile phase was 90% acetonitrile containing 10 mM ammonium bicarbonate buffer (pH 10.5) and 0.1% InfinityLab deactivator additive. The total flow rate of the mobile phase was 0.4 ml/min. Linear gradient separation was achieved as follows: 0–2 min, 75% B; 2–12 min, 75%−2% B; 12–15 min, 2% B. Mass spectrometric detection of these molecules was performed by selected reaction monitoring (SRM) using a LCMS-8050 triple quadrupole mass analyzer (Shimadzu corporation, Kyoto, Japan).

2.5 ALSFRS-R scoring

The ALSFRS-R scores of 25 ALS patients whom the peripheral blood was collected from were assessed by two neurologists. ALSFRS-R consists of 12 categories including speaking, eating, and respiratory ability, each of which is scored between 0 and 4 points. Scores decrease along with increasing functional exacerbation, and thus the total ALSFRS-R scores of ALS patients with normal and the worst functional status sum up as 48 (maximum) and 0 (minimum) points, respectively.

2.6 Statistical analysis

Statistical analysis was performed by SPSS software ver.26. Data are expressed as the mean ± standard deviation. Differences between two or more groups were analyzed using two-tailed Student's t-test. Statistical significance was set at p < 0.05. Variable PBMC data of ALS patients were processed by SIMCA-P software (Umetrics, Umeå, Sweden) for the evaluation of statistical outliers.

3 Results

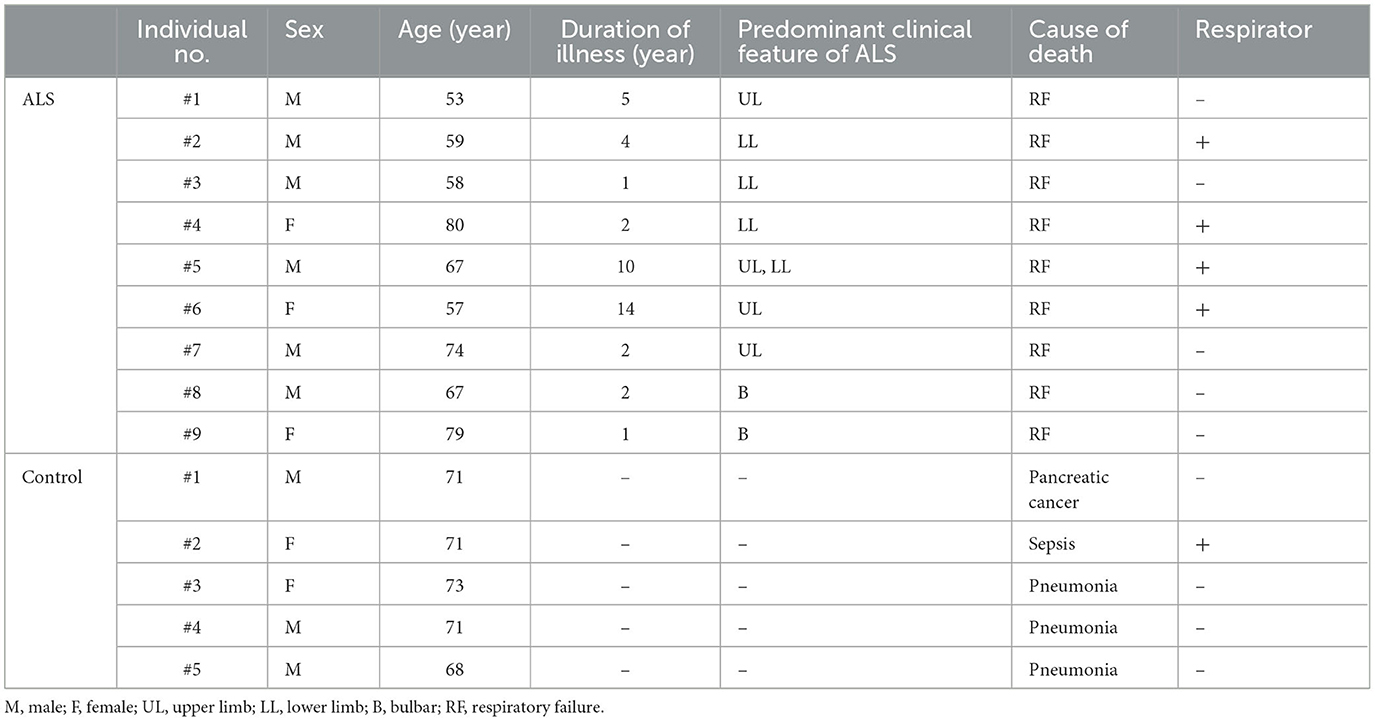

3.1 Elevated IP7 level in the spinal cord of ALS model mice

We previously showed that IP6K2 mRNA level was increased in the spinal cord of ALS patients, implying elevated production of IP7 in the ALS spinal cord (16, 17). To verify this hypothesis, we analyzed IP7 and its precursor IP6 in the CNS of ALS mouse model SOD1(G93A) transgenic (TG) mice at the three different breeding points, namely 12-week age (before ALS onset), 15-week age (early-middle stage of ALS), and 18-week age (late stage of ALS; Figure 1A). These TG mice become impairing their motor activity around 16-week age and almost completely lose lower limb mobility with the moribund state around 18-week age, which is in accordance with a previous report (22). LC-MS analysis showed that IP7 level was significantly increased in the spinal cord of the TG mice compared with that of littermate control mice at 18-week age (late stage of ALS), while its level did not significantly change in cerebrum and cerebellum of the same mice (Figures 1B, C). In the spinal cord of TG mice at 18-week age, IP6 level was also increased slightly but not significantly. Thus, we observed elevated IP7 level in the spinal cord of a rodent ALS model at ALS progressive state.

Figure 1. Elevated IP7 level in the spinal cord of SOD1(G93A) TG mice in the ALS late stage. (A) Schematic illustration of the experimental workflow. SOD1(G93A) TG and their littermate WT mice at 12-week (before ALS onset), 15-week (ALS early-middle stage) and 18-week (ALS late stage) were sacrificed to harvest central nervous system (CNS) for LC-MS analysis. (B) The concentrations of IP6, IP7, and IP7/IP6 (product-to-precursor) ratio in the cerebrum, cerebellum and spinal cord of SOD1(G93A) TG and their littermate WT mice. The values shown represent the mean ± SD of four independent experiments and are expressed relative to the WT mice. P-values calculated by Student's t-test are given in parenthesis. Asterisks indicate statistical significance (p < 0.05) compared with WT mice. (C) Representative SRM chromatograms of IP6, IP7, and internal standard ITPP-d6 in the spinal cord of SOD1(G93A) TG and their littermate WT mice. The arrowheads indicate the SRM peaks of the corresponding analytes. IS, internal standard.

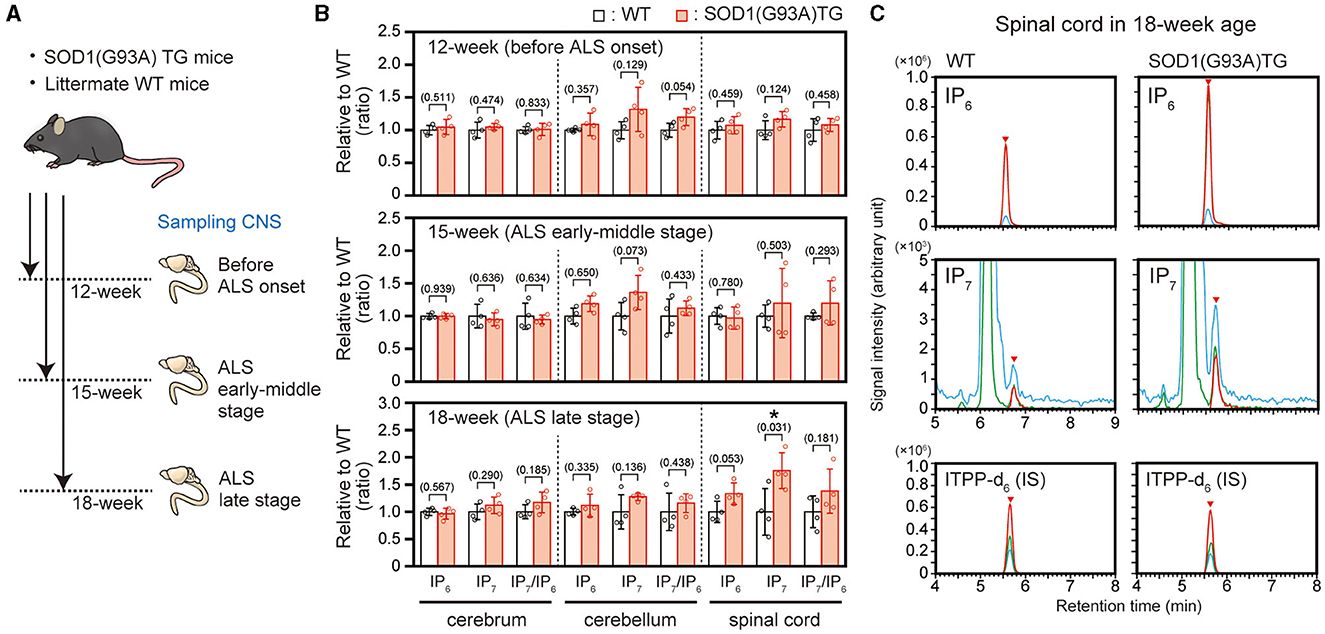

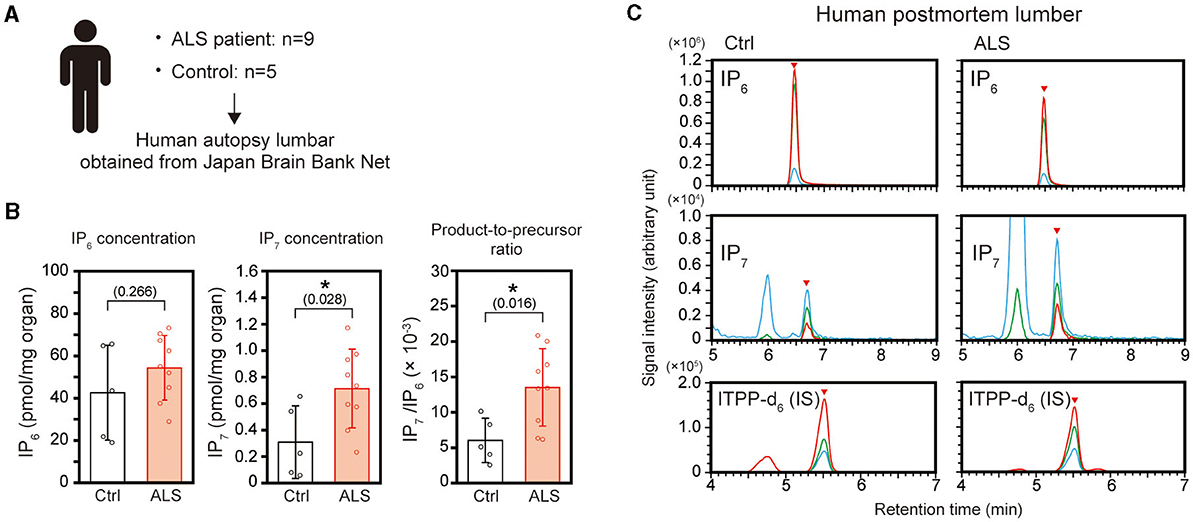

3.2 Elevated IP7 level in the postmortem spinal cord of ALS patients

To further confirm the elevated IP7 induction in the ALS spinal cord, we prepared 9 and 5 biopsies of human postmortem lumber cord from ALS patients and neurologically normal patients (control), respectively (Figure 2A and Table 1). The average ages of these two groups were 66.0 ± 9.96 for ALS patients and 70.8 ± 1.79 for control patients. All ALS patients examined were at the late stage of the disease and died by respiratory failure manifested as ALS-related dysfunction. IP7 level and the product-to-precursor (IP7/IP6) ratio were significantly increased in the postmortem lumber cord of the ALS patients compared with that of controls, while IP6 level was comparable between these two groups (Figures 2B, C). Thus, we demonstrated that IP7 level and its production rate are significantly elevated in the human spinal cord during ALS disease state.

Figure 2. Elevation of IP7 level and its production rate in the postmortem lumber cord of ALS patients. (A) Schematic depiction of the experimental workflow. Human postmortem lumber cords of ALS patients (n = 9) and neurologically normal patients (control; n = 5) obtained from Japan Brain Bank Net were subjected to LC-MS analysis. (B) The concentration of IP6 (left panel), IP7 (middle panel), and IP7/IP6 (product-to-precursor) ratio (right panel) in the postmortem lumber cords of ALS patients and neurologically normal patients (controls). The values shown represent the mean ± SD of nine (ALS) and five (control) independent experiments. P-values calculated by Student's t-test are given in parenthesis. Asterisks indicate statistical significance (p < 0.05) compared with the controls. (C) Representative SRM chromatograms of IP6, IP7, and internal standard ITPP-d6 in the postmortem lumber of ALS patients and controls. The arrowheads indicate the SRM peaks of the corresponding analytes. Ctrl, control; IS, internal standard.

3.3 IP7 is not suitable for usage as biofluid-based biomarker for ALS diagnosis

Certain ALS-associated proteins such as NfL and TDP-43 exist in biofluids and are considered as promising biofluid-based biomarkers for ALS diagnosis (23). To assess the availability of IP7 as a biofluid-based diagnostic marker, we first analyzed CSF of 3 ALS patients. However, neither IP7 nor IP6 were detected in CSF samples (Figure 3A). We next attempted to analyze peripheral blood because our and other groups have shown that certain amount of IP7 is present in the human peripheral blood (18, 24, 25). By fractionation of human peripheral blood into cell subsets and plasma, we found that peripheral blood mononuclear cells (PBMCs) predominantly possess both IP6 and IP7 among major fractions of peripheral blood (Supplementary Figure 1). We analyzed the PBMCs of 25 ALS patients and excluded three of them as statistical outliers based on IP6 and IP7 levels, IP7/IP6 ratio, and ALSFRS-R values (Supplementary Figure 2). We next compared the levels of IP6, IP7, and IP7/IP6 ratio in the PBMCs of ALS patients (n = 22) with those in the age-matched healthy counterparts (n = 22; Figure 3B). The level of IP6, IP7, and IP7/IP6 ratio in the PBMCs were comparable between ALS patients and age-matched healthy counterparts (Figure 3C). Also, these values did not show significant correlations with ALSFRS-R (Supplementary Figure 3). Thus, we failed to suggest that IP7 can be used as an ALS biomarker using biofluid such as CSF and peripheral blood.

Figure 3. IP7 level in human CSF and PBMCs do not differentiate ALS patients from healthy controls. (A) Representative SRM chromatogram of IP6 (left panels), IP7 (middle panels), and internal standard (IS) ITPP-d6 (right panels) in the CSF of ALS patients. Three mL of CSF was used for this analysis. SRM peaks of these molecules obtained by analyzing these standards were shown as reference. The arrowheads indicate the SRM peaks of the corresponding analytes. Neither IP6 nor IP7 were detected in any of the human CSF collected in this study. (B) Schematic illustration of the experimental workflow. Twenty milliliters of peripheral blood was collected from ALS patients (n = 25) and age-matched volunteers without any neurological disorder (control; n = 22). Harvested PBMCs were processed to isolate IP6 and IP7, which were analyzed by LC-MS. (C) The concentration of IP6 (left panel), IP7 (middle panel), and IP7/IP6 (product-to-precursor) ratio (right panel) in the PBMCs of ALS patients and controls. The values shown represent the mean ± SD of each 22 independent experiments. P-values calculated by Student's t-test are given in parenthesis. Ref, reference; Ctrl, control; IS, internal standard; n.s., not significant.

4 Discussion

While a number of studies have identified causative proteins and potential biomarkers for ALS so far (6), such exploring efforts still continue to understand the molecular machinery of this disease more precisely. Several studies reported the implicit findings that inositol pyrophosphate IP7 might be associated with ALS pathogenesis (14–17), but there has been no direct evidence proving this notion. In this study, we analyzed IP7 and its precursor IP6 in ALS model mice and ALS patients by an originally-designed LC-MS protocol (18, 19) to directly examine the relationship between IP7 and ALS.

We used a canonical ALS mouse model SOD1(G93A) TG mice to analyze IP7 level and metabolism before and after ALS onset and found that IP7 level significantly increased in the spinal cord of the TG mice at the late stage of the disease (Figures 1B, C). The spinal cord of the TG mice showed slightly but not significantly elevated IP7 metabolism (IP7/IP6 ratio) due to the up-regulation of IP6 level concomitantly with IP7 elevation, implying dysregulation of the metabolic pathway in lower inositol phosphates (IPs). A recent transcriptome analysis using the TG mice exhibited that mRNA levels of certain genes involved in phosphatidyl inositol metabolic process such as INPP5D (inositol polyphosphate-5-phosphatase D) and INPPL1 (inositol polyphosphate phosphatase like 1) was changed in the spinal cord at ALS disease state (26). Such alteration in inositol phospholipid pathway might lead to the dysregulated metabolism of IP7 and other lower inositol phosphates. Similar with the results of this rodent ALS model, significant elevation of IP7 level and metabolism was observed in the postmortem lumber of human ALS patients (Figures 2B, C). Considering our previous data that the transcript level of IP7-synthesizing enzyme IP6K2 increased in the spinal cord of ALS disease state (16), transcriptional activation of this enzyme is likely to contributes to IP7 elevation in the spinal cord of ALS.

The molecular mechanism underlying IP7 induction in the ALS condition is still elusive, but IP7 and its synthesizing kinase IP6Ks has been shown to associate with several neurodegeneration-related proteins. In our previous report, IP6K2 interacts with TDP-43 and promotes TDP-43-inducing cell death (17). A recent study identified IP7 kinase PPIP5K as an α-synuclein neurotoxicity modulator by functional RNAi screening using nematode Perkinson's disease model (27). Moreover, IP6K and IP7 facilitate the formation of aberrant protein-RNA aggregates inducing neurotoxicity in various neurodegenerative disorders (28) at least via promoting the interaction of RNA-binding proteins (for IP6K) and inhibiting the 5′-decapping reaction of non-translated mRNAs (for IP7) (29, 30). In addition, IP7 competitively binds to AKT and inhibits its downstream signaling including mTOR, a key regulator of cell survival (31, 32) (Information of proteins associating with IP6 was summarized in Supplementary Figure 4). These pieces of knowledge suggest that IP7 could regulate various neurodegenerative-related proteins in a multifaceted manner. However, we did not investigate pathobiological role of IP7 in the CNS of ALS model mice because the major barrier for studying IP7 functions in mouse models is the difficulty to efficiently inhibit IP7 production in vivo. Two genes IP6K1 and IP6K2 are responsible for IP7 production, but the deletion of both genes results in embryonic death and the deletion of single gene partially inhibits its production in the CNS as shown in our recent report (19). Recent report showed that a novel IP6K inhibitor efficiently blocks IP7 production in vivo (24), which will enable to investigate the role of IP7 in ALS using disease model mice. Further investigation will be warranted to prove the notion that elevated IP7 is associated with progressive degeneration of spinal motor neurons during ALS.

Since several ALS-associated molecules such as NfL and TDP-43 are promising for applying biofluid-based ALS diagnostic markers (23), we examined the applicability of IP7 in such diagnostic approach using peripheral blood and CSF. Among human peripheral blood fractions, PBMCs possessed most abundant IP6 and IP7 (Supplementary Figure 1), but the levels of these molecules in PBMCs could not differentiate ALS patients from age-matched healthy individuals (Figure 3C), suggesting the unfeasibility of peripheral blood IP7 for usage as an ALS diagnostic marker. In addition, our LC-MS analysis could not detect IP7 and IP6 in human CSF, suggesting that the abundances of these molecules in CSF are less than 0.3 μM considering the lower limit of detection in our LC-MS protocol (18, 19). It would be necessary to evaluate CSF IP7 level by more sensitive protocol such as capillary electrophoresis-mass spectrometry (CE-MS) (33) or develop a technology whereby spinal cord IP7 is measured non-invasively for considering the application of IP7 for ALS diagnosis.

Although this study focused at the relationship between IP7 and ALS in this study, it is meaningful to elucidate if IP7 level and its metabolism would be altered in other neurodegenerative disorders. So far, IP7 has been implied to be associated with certain neurodegenerative diseases such as Huntington's disease (34) and Alzheimer's disease (35). Sensitive mass spectrometric analysis of IP7 using clinical biopsies as well as mouse disease models would unveil a pathobiological role of IP7 in such diseases in future.

Recently, CE-MS analysis clarified that several IP7 isotypes such as 4/6-IP7 and 1/3-IP7 constitute mammalian IP7 in addition to 5-IP7, an already-known isotype of mammalian IP7 (25). Due to the technical limitation of LC-MS, we could not determine if the IP7 status would be affected during ALS at the level of isotype. Further investigation is required which isotypes of IP7 is elevated in the spinal cord of ALS disease state.

We demonstrate for the first time that IP7 level and/or its metabolism (IP7/IP6 ratio) were significantly elevated in mouse and/or human ALS spinal cord compared with neurologically normal counterparts in a direct way. On the other hand, this study showed several limitations. First, the sample number of postmortem ALS spinal cord isn't necessarily sufficient for the statistical analysis. Secondly, we failed to demonstrate IP7 level and its metabolism as biofluid-based diagnostic parameters for ALS. Lastly, we could not clarify the molecular basis and pathophysiological significance of IP7 elevation during ALS disease state. We believe that further investigation of IP7 function in ALS pathology will lead to the development of novel diagnostic and therapeutic approach for this incurable disease.

Data availability statement

The original contributions presented in the study are included in the article/Supplementary material, further inquiries can be directed to the corresponding author/s.

Ethics statement

The studies involving humans were approved by the Clinical Investigation Committee at Tokai University School of Medicine. The studies were conducted in accordance with the local legislation and institutional requirements. The participants provided their written informed consent to participate in this study. The animal study was approved by the Institutional Animal Care and Use Committee at Tokai University. The study was conducted in accordance with the local legislation and institutional requirements. Written informed consent was obtained from the individual(s) for the publication of any potentially identifiable images or data included in this article.

Author contributions

MI: Formal analysis, Investigation, Methodology, Visualization, Writing—original draft, Writing—review & editing. NF: Investigation, Writing—review & editing. SK: Investigation, Writing—review & editing. MTan: Formal analysis, Writing—review & editing. MTak: Funding acquisition, Resources, Writing—review & editing. BM: Resources, Writing—review & editing. YS: Funding acquisition, Resources, Writing—review & editing. AM: Writing—review & editing. TN: Writing—review & editing. SN: Writing—review & editing. NS: Writing—review & editing. AK: Funding acquisition, Resources, Writing—review & editing. EN: Conceptualization, Funding acquisition, Project administration, Supervision, Writing—review & editing.

Funding

The author(s) declare financial support was received for the research, authorship, and/or publication of this article. This work was partly supported by grants-in-aid numbers JP19K07851 and JP22K07379 for scientific research from Japan Society for the Promotion of Science (to EN), Japan Agency for Medical Research and Development under Grant Number JP21wm0425019 (to MTak and AK) and JP23jm0210097 (to AK), intramural funds from the National Center of Neurology and Psychiatry (to MTak), and the Collaborative Research Project of the Brain Research Institute of Niigata University (to AK).

Acknowledgments

We appreciate Japan Brain Bank Net for providing postmortem lumbers of ALS patients, Prof. Shunya Takizawa of Tokai University for fruitful suggestions, Prof. Shinji Hadano of Tokai University for providing SOD1 (G93A) TG mice, and the Support Center for Medical Research and Education of Tokai University for technical assistance.

Conflict of interest

The authors declare that the research was conducted in the absence of any commercial or financial relationships that could be construed as a potential conflict of interest.

Publisher's note

All claims expressed in this article are solely those of the authors and do not necessarily represent those of their affiliated organizations, or those of the publisher, the editors and the reviewers. Any product that may be evaluated in this article, or claim that may be made by its manufacturer, is not guaranteed or endorsed by the publisher.

Supplementary material

The Supplementary Material for this article can be found online at: https://www.frontiersin.org/articles/10.3389/fneur.2023.1334004/full#supplementary-material

References

1. Marin B, Fontana A, Arcuti S, Copetti M, Boumédiene F, Couratier P, et al. Age-specific ALS incidence: a dose-response meta-analysis. Eur J Epidemiol. (2018) 33:621–34. doi: 10.1007/s10654-018-0392-x

2. Mehta P, Kaye W, Raymond J, Punjani R, Larson T, Cohen J, et al. Prevalence of amyotrophic lateral sclerosis – United States, 2015. MMWR Morb Mortal Wkly Rep. (2018) 67:1285–9. doi: 10.15585/mmwr.mm6746a1

3. Marin B, Boumédiene F, Logroscino G, Couratier P, Babron MC, Leutenegger AL, et al. Variation in worldwide incidence of amyotrophic lateral sclerosis: a meta-analysis. Int J Epidemiol. (2017) 46:57–74. doi: 10.1093/ije/dyw061

4. Feldman EL, Goutman SA, Petri S, Mazzini L, Savelieff MG, Shaw PJ, et al. Amyotrophic lateral sclerosis. Lancet. (2022) 400:1363–80. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(22)01272-7

5. Brown RH, Al-Chalabi A. Amyotrophic lateral sclerosis. N Engl J Med. (2017) 377:162–72. doi: 10.1056/NEJMra1603471

6. Masroni P, Van Damme P. Amyotrophic lateral sclerosis: a clinical review. Eur J Neurol. (2020) 27:1918–29. doi: 10.1111/ene.14393

7. van Es MA, Hardiman O, Chio A, Al-Chalabi A, Pasterkamp RJ, Veldink JH, et al. Amyotrophic lateral sclerosis. Lancet. (2017) 390:2084–98. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(17)31287-4

8. Turner MR, Kiernan MC, Leigh PN, Talbot K. Biomarkers in amyotrophic lateral sclerosis. Lancet Neurol. (2009) 8:94–109. doi: 10.1016/S1474-4422(08)70293-X

9. Bridel C, van Wieringen WN, Zetterberg H, Tijms BM, Teunissen CE, The NFL Group. Diagnostic value of cerebrospinal fluid neurofilament light protein in neurology: a systematic review and meta-analysis. JAMA Neurol. (2019) 76:1035–48. doi: 10.1001/jamaneurol.2019.1534

10. Benatar M, Zhang L, Wang L, Granit V, Statland J, Barohn R, et al. Validation of serum neurofilaments as prognostic and potential pharmacodynamic biomarkers for ALS. Neurology. (2020) 95:e59–69. doi: 10.1212/WNL.0000000000009559

11. Pisani F, Livermore T, Rose G, Chubb JR, Gaspari M, Saiardi A. Analysis of Dictyostelium discoideum inositol pyrophosphate metabolism by gel electrophoresis. PLoS ONE. (2014) 9:e85533. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0085533

12. Ingram SW, Safrany ST, Barnes LD. Disruption and overexpression of the Schizosaccharomyces pombe aps1 gene, and effects on growth rate, morphology and intracellular diadenosine 5′,5″'-P1,P5-pentaphosphate and diphosphoinositol polyphosphate concentrations. Biochem J. (2003) 369:519–28. doi: 10.1042/bj20020733

13. Menniti FS, Miller RN, Putney JW Jr, Shears SB. Turnover of inositol polyphosphate pyrophosphates in pancreatoma cells. J Biol Chem. (1993) 268:3850–6. doi: 10.1016/S0021-9258(18)53551-1

14. Nagata E, Luo HR, Saiardi A, Bae BI, Suzuki N, Snyder SH. Inositol hexakisphosphate kinase-2, a physiologic mediator of cell death. J Biol Chem. (2005) 280:1634–40. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M409416200

15. Onnebo SM, Saiardi A. Inositol pyrophosphates modulate hydrogen peroxide signalling. Biochem J. (2009) 423:109–18. doi: 10.1042/BJ20090241

16. Moriya Y, Nagata E, Fujii N, Satoh T, Ogawa H, Hadano S, et al. Inositol hexakisphosphate kinase 2 is a presymptomatic biomarker for amyotrophic lateral sclerosis. Tokai J Exp Clin Med. (2017) 42:13–8.

17. Nagata E, Nonaka T, Moriya Y, Fujii N, Okada Y, Tsukamoto H, et al. inositol hexakisphosphate kinase 2 promotes cell death in cells with cytoplasmic TDP-43 aggregation. Mol Neurobiol. (2016) 53:5377–83. doi: 10.1007/s12035-015-9470-1

18. Ito M, Fujii N, Wittwer C, Sasaki A, Tanaka M, Bittner T, et al. Hydrophilic interaction liquid chromatography-tandem mass spectrometry for the quantitative analysis of mammalian-derived inositol poly/pyrophosphates. J Chromatogr A. (2018) 1573:87–97. doi: 10.1016/j.chroma.2018.08.061

19. Ito M, Fujii N, Kohara S, Hori S, Tanaka M, Wittwer C, et al. Inositol pyrophosphate profiling reveals regulatory roles of IP6K2-dependent enhanced IP7 metabolism in the enteric nervous system. J Biol Chem. (2023) 299:102928. doi: 10.1016/j.jbc.2023.102928

20. Brooks BR, Miller RG, Swash M, Munsat TL, World World federation of neurology research group on motor neuron diseases. El escorial revisited: revised criteria for the diagnosis of amyotrophic lateral sclerosis. Amyotroph Lateral Scler Other Motor Neuron Disord. (2000) 1:93–299. doi: 10.1080/146608200300079536

21. Wilson MS, Bulley SJ, Pisani F, Irvine RF, Saiardi A. A novel method for the purification of inositol phosphates from biological samples reveals that no phytate is present in human plasma or urine. Open Biol. (2015) 5:150014. doi: 10.1098/rsob.150014

22. Julien JP, Kriz J. Transgenic mouse models of amyotrophic lateral sclerosis. Biochim Biophys Acta. (2006) 1762:1013–24. doi: 10.1016/j.bbadis.2006.03.006

23. Kasai T, Kojima Y, Ohmichi T, Tatebe H, Tsuji Y, Noto Y, et al. Combined use of CSF NfL and CSF TDP-43 improves diagnostic performance in ALS Ann Clin Transl Neurol. (2019) 6:2489–502. doi: 10.1002/acn3.50943

24. Moritoh Y, Abe SI, Akiyama H, Kobayashi A, Koyama R, Hara R, et al. The enzymatic activity of inositol hexakisphosphate kinase controls circulating phosphate in mammals. Nat Commun. (2021) 12:4847. doi: 10.1038/s41467-021-24934-8

25. Qiu D, Gu C, Liu G, Ritter K, Eisenbeis VB, Bittner T, et al. Capillary electrophoresis mass spectrometry identifies new isomers of inositol pyrophosphates in mammalian tissues. Chem Sci. (2022) 14:658–67. doi: 10.1039/D2SC05147H

26. Fernández-Beltrán LC, Godoy-Corchuelo JM, Losa-Fontangordo M, Williams D, Matias-Guiu J, Corrochano S, et al. Transcriptomic meta-analysis shows lipid metabolism dysregulation as an early pathological mechanism in the spinal cord of SOD1 mice. Int J Mol Sci. (2021) 22:9553. doi: 10.3390/ijms22179553

27. Vozdek R, Pramstaller PP, Hicks AA. Functional screening of Parkinson's disease susceptibility genes to identify novel modulators of α-synuclein neurotoxicity in Caenorhabditis elegans. Front Aging Neurosci. (2022) 14:806000. doi: 10.3389/fnagi.2022.806000

28. Rhine K, Al-Azzam N, Yu T, Yeo GW. Aging RNA granule dynamics in neurodegeneration. Front Mol Biosci. (2022) 9:991641. doi: 10.3389/fmolb.2022.991641

29. Sahu S, Wang Z, Jiao X, Gu C, Jork N, Wittwer C, et al. InsP7 is a small-molecule regulator of NUDT3-mediated mRNA decapping and processing-body dynamics. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. (2020) 117:19245–53. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1922284117

30. Shah A, Bhandari R. IP6K1 upregulates the formation of processing bodies by influencing protein-protein interactions on the mRNA cap. J Cell Sci. (2021) 134:jcs259117. doi: 10.1242/jcs.259117

31. Luo HR, Huang YE, Chen JC, Saiardi A, Iijima M, Ye K, et al. Inositol pyrophosphates mediate chemotaxis in dictyostelium via pleckstrin homology domain-PtdIns(3,4,5)P3 interactions. Cell. (2003) 114:559–72. doi: 10.1016/S0092-8674(03)00640-8

32. Chakraborty A, Koldobskiy MA, Bello NT, Maxwell M, Potter JJ, Juluri KR, et al. Inositol pyrophosphates inhibit Akt signaling, thereby regulating insulin sensitivity and weight gain. Cell. (2010) 143:897–910. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2010.11.032

33. Qiu D, Wilson MS, Eisenbeis VB, Harmel RK, Riemer E, Haas TM, et al. Analysis of inositol phosphate metabolism by capillary electrophoresis electrospray ionization mass spectrometry. Nat Commun. (2020) 11:6035. doi: 10.1038/s41467-020-19928-x

34. Nagata E, Saiardi A, Tsukamoto H, Okada Y, Itoh Y, Satoh T, et al. Inositol hexakisphosphate kinases induce cell death in Huntington disease. J Biol Chem. (2011) 286:26680–6. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M111.220749

35. Crocco P, Saiardi A, Wilson MS, Maletta R, Bruni AC, Passarino G, et al. Contribution of polymorphic variation of inositol hexakisphosphate kinase 3 (IP6K3) gene promoter to the susceptibility to late onset Alzheimer's disease. Biochim Biophys Acta. (2016) 1862:1766–73. doi: 10.1016/j.bbadis.2016.06.014

Keywords: amyotrophic lateral sclerosis, inositol pyrophosphate, diphosphoinositol pentakisphosphate, inositol hexakisphosphate, liquid chromatography-tandem mass spectrometry

Citation: Ito M, Fujii N, Kohara S, Tanaka M, Takao M, Mihara B, Saito Y, Mizuma A, Nakayama T, Netsu S, Suzuki N, Kakita A and Nagata E (2024) Elevation of inositol pyrophosphate IP7 in the mammalian spinal cord of amyotrophic lateral sclerosis. Front. Neurol. 14:1334004. doi: 10.3389/fneur.2023.1334004

Received: 06 November 2023; Accepted: 15 December 2023;

Published: 11 January 2024.

Edited by:

Elijah W. Stommel, Dartmouth College, United StatesReviewed by:

Christiana Christodoulou, The Cyprus Institute of Neurology and Genetics, CyprusKazumasa Saigoh, Kindai University Hospital, Japan

Debabrata Laha, Indian Institute of Science (IISc), India

Copyright © 2024 Ito, Fujii, Kohara, Tanaka, Takao, Mihara, Saito, Mizuma, Nakayama, Netsu, Suzuki, Kakita and Nagata. This is an open-access article distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution License (CC BY). The use, distribution or reproduction in other forums is permitted, provided the original author(s) and the copyright owner(s) are credited and that the original publication in this journal is cited, in accordance with accepted academic practice. No use, distribution or reproduction is permitted which does not comply with these terms.

*Correspondence: Eiichiro Nagata, enagata@is.icc.u-tokai.ac.jp; Masatoshi Ito, masatoshi.ito@marianna-u.ac.jp

Masatoshi Ito

Masatoshi Ito Natsuko Fujii1

Natsuko Fujii1 Masaki Takao

Masaki Takao Atsushi Mizuma

Atsushi Mizuma Eiichiro Nagata

Eiichiro Nagata