The palliative care needs and experiences of patients with advanced Parkinson’s disease: a qualitative scoping review

- 1School of Nursing, Hangzhou Normal University, Hangzhou, Zhejiang, China

- 2Zhejiang Haining Health School, Haining City, Zhejiang, China

- 3School of Nursing, Shanxi Medical University, Taiyuan, Shanxi, China

Aim: To determine the experiences and needs of palliative care in patients with advanced Parkinson’s disease (PD).

Methods: A scoping literature review methodology, as described by the Joanna Briggs Institute, was employed to search for relevant literature. An electronic search of studies published in English was conducted across five databases from inception to 10 September 2023.

Results: The search yielded a total of 1,205 articles, with 20 meeting the inclusion criteria. The findings were organized into four themes: (1) unmet emotional and informational needs; (2) needs for effective coordination of care; (3) planning for the future; and (4) symptom management. This scoping review highlights the intricate nature of palliative care for patients with PD and sheds light on issues within current palliative care healthcare systems. The findings emphasize the necessity for individualized interventions and services to address the diverse unmet palliative care needs of people with PD.

Conclusion: The study reveals the complex landscape of palliative care for individuals with advanced PD, emphasizing the inadequacies within existing healthcare systems. The identified themes underscore the importance of tailored interventions to address the varied unmet palliative care needs of this population.

1 Introduction

Parkinson’s disease (PD) is a progressive neurodegenerative disease characterized by motor and non-motor symptoms (1). In 2016, it was estimated that PD affected 6.1 million people worldwide, and it is expected that the rate of growth in numbers of patients will be the highest of all neurological disease, even that of Alzheimer’s disease (2). The progression of PD can be described as experiencing a phase trajectory, starting from the “honeymoon” phase where symptoms are almost entirely alleviated due to medication, followed by the motor complications phase, the neuropsychiatric phase, and finally entering the palliative phase (3). The treatment for early-stage PD is entirely different from that of the advanced stage. Early-stage PD treatment requires minimizing motor disturbances and reducing the occurrence of both motor and non-motor off times to maximize independent motor function. However, in the advanced stage, patients with advanced PD have escalating disabilities and a rising number of symptoms, there are almost no available treatment options, and the focus of treatment shifts to addressing primary non-motor symptoms with more supportive and palliative measures (4). Therefore, palliative care is especially important for patients with advanced Parkinson’s disease.

According to the WHO definition (5), palliative care is an approach aimed at enhancing the wellbeing of patients and their families when dealing with challenges related to serious illnesses. This involves early identification, thorough assessment, and effective management of pain and other concerns, whether they are physical, emotional, or spiritual. Advanced PD presents a significant symptom burden, encompassing pain, fatigue, daytime drowsiness, mobility issues, depression, cognitive impaired, and so on, which requiring timely planning and potential end-of-life considerations (6). Moreover, advanced PD imposes a substantial strain on caregivers, making their caregiver roles challenging. A meta-ethnography highlighted the complex and dynamic experiences of family caregivers for PD patients, underlining the heavy burden associated with caring for those with PD (7).

There is evidence showing that palliative care specialists in multidisciplinary PD clinics can improve patients’ and caregivers’ quality of life as well as other outcomes (8). Palliative care has been demonstrated to improve self-perception and minimize stress, anger, and loss of control (9, 10). Additionally, it helped patients with their disease burden (11). Despite these potential benefits, there is still confusion about the role of palliative care in PD progression, and palliative care participation is likely being underutilized. PD patients are less likely to obtain palliative care services than patients with other neurological disorders, a study found that hospice deaths were exceedingly rare in patients with PD, occurring in just 0.6% of this population (12). Patients with advanced PD in Germany have a drastically deteriorated quality of life, with 72% having an unmet need for palliative care and only 2.6% having contact with palliative care providers (13).

As the potential benefits of palliative care for advanced PD are gradually acknowledged, an increasing number of researchers are turning to qualitative research methods to explore the specific needs and experiences of this group regarding palliative care. Compared to quantitative research, qualitative studies provide a deeper understanding, helping researchers interpret the complexity, depth, and meaning of certain phenomena (14). However, there currently exists no literature review specifically focused on qualitative research concerning the palliative care needs and experiences of patients with advanced PD. A scoping review can provide comprehensive insights and is crucial in showcasing the types of evidence that can inform practice and identify significant areas lacking evidence (15). Therefore, through this qualitative scoping review, our aim is to comprehensively understand and identify the palliative care needs and experiences of patients with advanced PD and their caregivers. By doing so, we aspire to make significant contributions to the development of pertinent care models and to pinpoint areas for future investigation.

2 Methods

The five-stage scoping review framework proposed by Arksey and O’Malley (16) was employed. The goal was to compile a list of advanced PD patients’ palliative care needs and experiences. Because of the scoping review’s nature, no attempt was made to assess the quality of the papers included. Instead, the review was guided by the five-stage methodology shown below.

2.1 Determining the study question

This stage entails determining the research question as well as this review’s principal goal. The primary goal of this study was to compile current evidence on the needs and experiences of patients with advanced PD in palliative care from the perspectives of patients and their caregivers. The research question was: What are the needs and experiences of patients with advanced PD and their caregivers in terms of palliative care?

2.2 Identifying relevant studies

The literature was thoroughly assessed in the following five databases from the inception (1 January 1952) to 10 September 2023: PubMed, Embase, EBSCOhost CINAHL, ProQuest, and Scopus. Two members of the research team designed a keyword-based search strategy, which was approved by the third member of the research team. We are using the key words Parkinson’s disease, palliative care, qualitative research identified as relevant Medical Subject Headings (MeSH). Free text words added to the search were supportive care, qualitative, need*, experience*, and so on, see Supplementary File 1. The different keywords were combined using Boolean operators, such as AND or OR. Thesaurus phrases were chosen to complement the keywords based on an individual database. All of the included articles’ reference lists were also meticulously searched for any other papers that discussed palliative care experiences and requirements.

2.3 Study selection

The literature period was from 1 January 1952 to 10 September 2023, to assure the theme’s comprehensiveness. For the selection of studies, the following inclusion criteria were considered: (a) original qualitative research articles which detailed participants’ direct reports of their supportive and palliative care needs; (b) made available in the full version; and (c) English languages. Exclusion criteria were defined: (a) a mixed population and not focus on advanced PD separately; (b) the sample of advanced PD less than 50%; (c) the focus of the article was medical/clinical treatment, deep brain stimulation, or prognostication or reporting unmet supportive care needs specific to the COVID-19 pandemic (outside of scope); (d) focusing on a single aspect of palliative care services (e.g., spiritual care only); and (e) conferences, public policies, and videos. The scoping review’s inclusion and exclusion criteria were determined after obtaining knowledge with the existing literature on palliative care. The first phase of screening looked at the titles and abstracts to see if they met the inclusion and exclusion criteria. The entire texts of selected papers from the first round of screening were assessed in the second step. Any discrepancies between the two reviewers were resolved by a two-reviewer consensus or the consultation of a third reviewer to confirm the final inclusion.

2.4 Charting the data

Depending on the research questions, the following essential pieces of data from the included publications were compiled in an iteratively designed data chart form: first author, country, aims, setting, participants, methods, and findings. This chart form was used to compile data from all of the listed studies in a narrative format.

2.5 Compiling, analyzing, and reporting the findings

We used six steps of thematic analysis (17) to define the needs: (1) Familiarization with the data: two researchers repeatedly read the included literature to become thoroughly acquainted with it. (2) Generating initial codes: once familiar with the data, the next step involves coding the data. In our research, this was done independently by the two team members. Coding involves highlighting words, phrases, or sections of the data that appear significant and tagging them with a descriptive label. (3) Searching for themes: after coding, the next step is to collate codes into potential themes. In our research, this involved an iterative process where coding results were continuously revised until the themes comprehensively covered all needs and experiences mentioned in the literature. (4) Reviewing themes: this involves refining and defining the themes to ensure they have a clear scope and focus. To ensure consistency and validate the process, two reviewers conducted a thematic analysis separately. (5) Defining and naming themes: once the themes are refined, they are clearly defined and named. The results were segmented into literature aspects and subthemes that address PD patients’ palliative care experiences and needs. (6) Producing the report: after performing critical comparisons and debates, the research team unanimously supported the findings.

3 Results

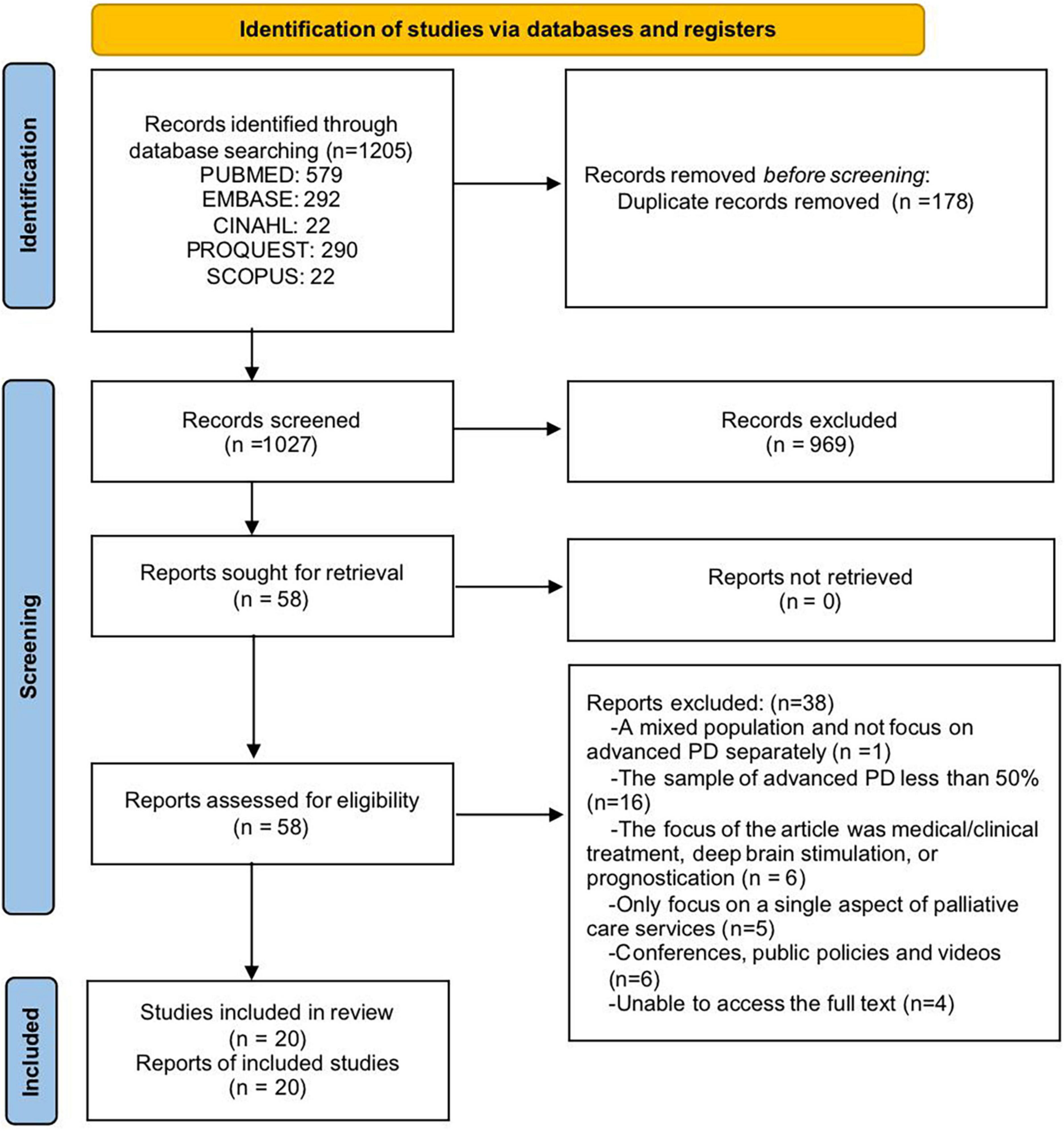

Our search yielded 1,206 articles from the five databases combined. After excluding duplicates (n = 178), the titles and abstracts of the remaining 1,027 studies were screened, and 58 articles were subjected to full-text reviews. Based on the inclusion and exclusion criteria, 20 studies were identified as eligible for this study. A flowchart of the search strategy and selection procedure is shown in Figure 1.

Figure 1. PRISMA diagram of the literature search. Adapted from Page et al. (58).

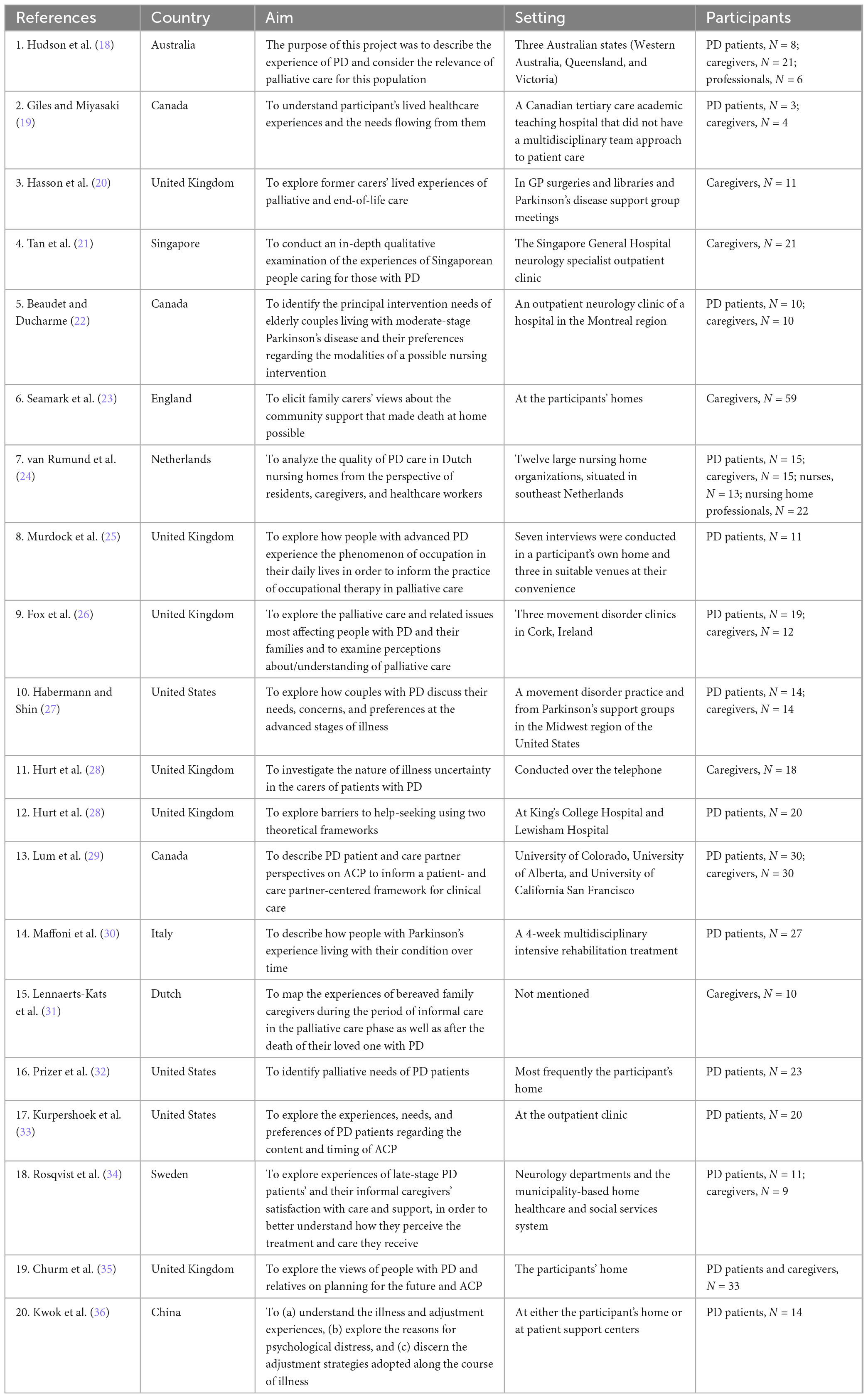

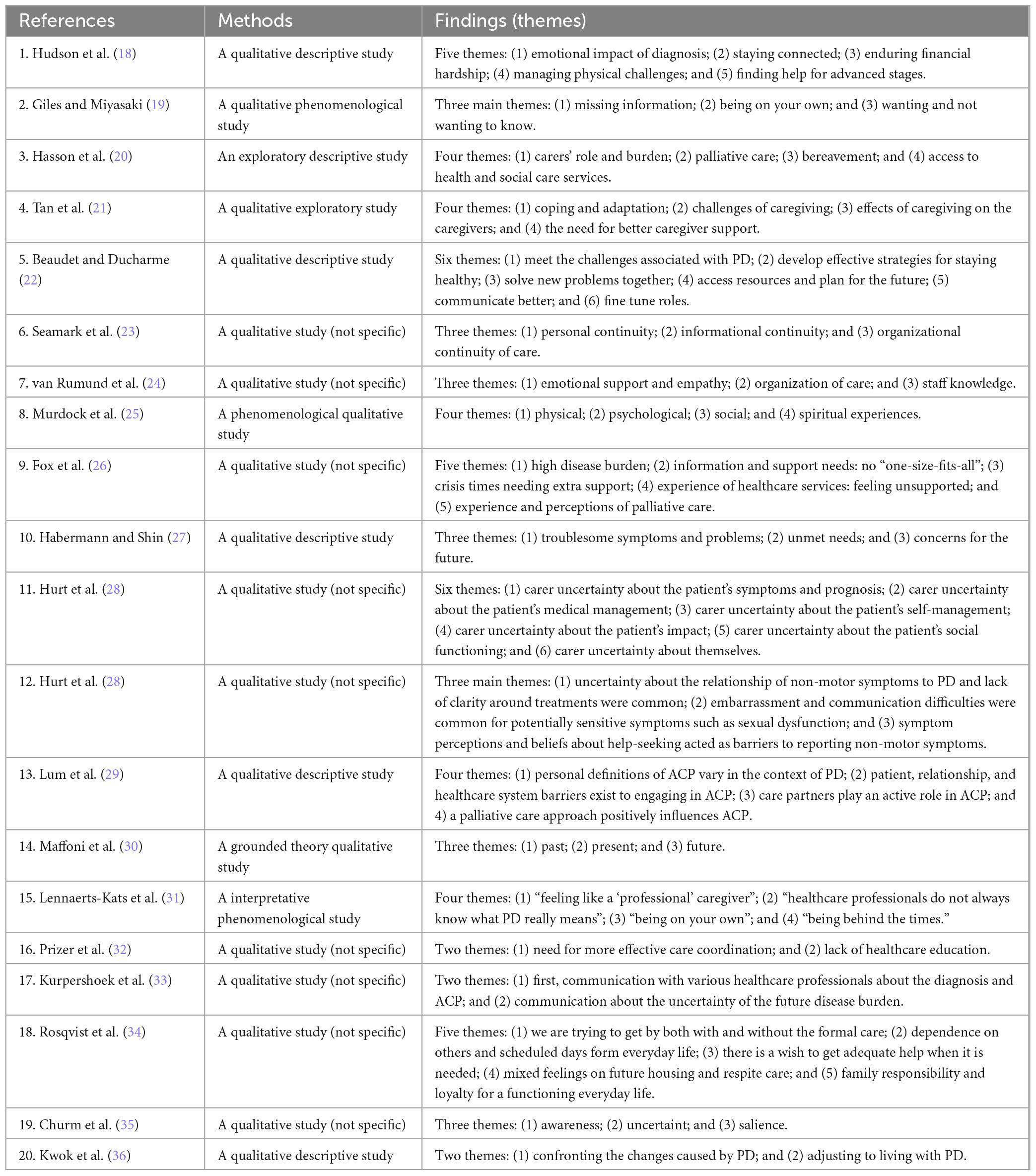

3.1 Aspects of the literature

The general elements of the reviewed literature are presented in Table 1. Most of the 20 studies included were performed in the United Kingdom (n = 7), and the remaining were from the United States (n = 3), Canada (n = 3), Netherlands (n = 1), Italy (n = 1), Australia (n = 1), Dutch (n = 1), Singapore (n = 1), Sweden (n = 1), and China (n = 1). There were 533 participants (238 patients, 254 caregivers, and 41 healthcare professionals). Among these 20 papers, 6 focused solely on the perspectives of PD patients, 5 focused solely on the perspectives of PD caregivers, 7 presented information on the patients and caregivers, and the other paper on the patients, caregivers, and healthcare professionals. The precise elements of the papers included are described in Tables 1, 2.

3.2 Experience and needs of palliative care

Based on a thematic analysis, four main themes emerged: (1) unmet emotional and informational needs; (2) needs for effective coordination of care; (3) planning for the future; and (4) symptom management.

3.2.1 Theme 1: unmet emotional and informational needs

This theme is prominently addressed across the included literature (18–22, 24, 26–28, 31–36). Upon receiving a diagnosis of PD, patients and their family members often grapple with intense emotional turmoil, characterized by profound sadness and apprehensions about the future. Family caregivers describe the impact of the diagnosis with phrases such as “the bottom fell out of his world” and “he was broken-hearted” (18). This emotional upheaval is intricately linked to the unpredictable trajectory of the disease (19, 24, 26, 36).

However, when seeking information regarding prognosis, diagnosis, and home care services, patients and their families frequently encounter information gaps (19, 22, 26, 27, 33). Some are unsure about what questions to pose, while others are apprehensive about potential reprimands from physicians for making inquiries (19). Many patients report a sense of isolation due to a lack of sufficient information post-diagnosis. Some families turn to the internet for answers (19), and certain caregivers express a desire for more proactive and clear medical guidance (31, 34). Uncertainty emerges as a prevalent topic (28, 35), with both the unpredictability of the future and mixed messages regarding PD progression amplifying patient distress (20, 32).

Moreover, caregivers frequently note that their lifestyle is constrained, their roles have shifted, and they experience physical and emotional fatigue (21, 22, 28). They articulate an urgent need for enhanced caregiving support and more comprehensive guidance on PD management. Concurrently, both patients and caregivers indicate that their interactions with medical professionals often lack a sense of adequate support (32, 34). In summary, the unmet needs faced by PD patients and their families encompass a strong demand for emotional support and specialized information.

3.2.2 Theme 2: needs for effective coordination of care

The theme of “needs for effective coordination of care” has been consistently emphasized in the selected literature. Most caregivers explicitly state their need for a more integrated care package, allowing them to regularly interact with experts and to be clearly directed to other types of services and information (20). This further underscores the notion that adopting a more integrated approach to PD services can enhance the effectiveness of the healthcare system (21). Continuity is a fundamental aspect of this theme. Family caregivers particularly value the consistent care from one or two primary caregivers or nurses, transitioning the relationship from strangers to trusted aides (23). However, frequent changes in nursing personnel are viewed negatively. The continuity of information becomes a focal point, with family caregivers having low expectations for information transfer between different care institutions. Many reported negative experiences related to information dissemination and communication (23). When the organizational aspect of care runs smoothly, family caregivers feel comforted and encouraged. Yet, many also reported negative facets of care organization, especially outside of working hours (23).

Budget constraints, frequent staff turnover, and time pressures are identified as challenges, all affecting the quality of care (24). This operational inefficiency leaves many feeling isolated, a sentiment exacerbated by limited interactions with the medical team. This often leads to a noticeable lack of ongoing support and service coherence (26). Communication between healthcare providers is a recurrent concern. Many participants feel that there is little communication among their doctors (32). Moreover, most feel that care is not well-integrated throughout the medical system, highlighting challenges in managing and coordinating care (32). Patients and caregivers express a preference for more frequent contact with PD specialists or neurologists. A common sentiment is that non-specialist medical institutions often lack adequate PD-specific knowledge, leading to mistakes, especially concerning medications (34). Many patients hope for more physiotherapy, emphasizing a shortage of specialized PD physiotherapy. Assistive devices and housing adaptations are deemed essential for daily living. In summary, there is a widespread desire among participants to receive appropriate assistance when needed. The capability and continuity of healthcare personnel are deemed crucial, especially in home healthcare. Challenges arising from staff turnover and communication errors are frequently lamented. There is a general hope for more flexibility and personalization in home healthcare (20).

3.2.3 Theme 3: planning for the future

The theme of “planning for the future” pertains to how caregivers and patients anticipate and make plans for the progression of the disease and their perspectives on advance care planning (ACP). Most caregivers are pained by witnessing the physical and mental decline of patients. While they understand that death is inevitable, they still hope for the patient to remain at home for as long as possible (20, 34). Many Parkinson’s disease patients and their spouses strongly express the desire to stay in their homes for an extended duration. They are concerned about the lack of information that would help them make informed decisions for the future (27). Both patients and caregivers are keen to understand available resources, how to access them, and how to adequately plan for the future, emphasizing the importance of understanding and navigating available services (22).

Advance care planning is an emotionally charged topic, with varied opinions on when and how it should be approached. While some individuals remain hopeful about future treatments and do not wish to contemplate the end of life, others have given profound thought to care directives (26). Although many participants are not well-acquainted with or have misconceptions about palliative care (35), those who have experienced specialized palliative care hold it in high regard, recognizing its potential benefits in symptom control and support (26). In terms of communication around ACP, a majority of patients wish to discuss ACP with their healthcare providers to anticipate what the future may hold (33). While many have discussed issues related to ACP with their families (29), only a few have had such discussions with their medical teams. They express concerns about potential future symptoms, such as living in a wheelchair, becoming dependent, becoming a burden to their family, or having to reside in a nursing home (33). Many fear the onset of dementia and hope that discussions around ACP can address these uncertainties (33).

3.2.4 Theme 4: symptom management

The theme of “symptom management” primarily focuses on how PD patients and caregivers confront, cope with, and manage the myriad symptoms of the disease. Symptom management encompasses various considerations. For instance, PD patients discuss a range of symptoms, like tremors, stiffness, and mobility issues, with a special focus on the common problems of “foot freezing” and movement difficulties (25). Medication is crucial in managing these symptoms, yet its “on/off” nature and side effects still have a negative impact on daily life (25). Also, the loss of speech and social interaction abilities, make it difficult for patients to communicate with others (18). Moreover, psychological and social experiences, such as sleep disorders, fatigue, depression, anxiety, stress, work, and recreational activities, are also pivotal aspects for PD patients to consider in symptom management (25, 37). In summary, PD patients face multifaceted challenges in symptom management. They have to deal not only with physical difficulties but also with psychological, social, and spiritual issues (30).

For caregivers, dealing with the patient’s increasingly severe symptoms poses a challenge. They frequently feel anxious and fearful, especially when the patient starts losing balance and falling. Family caregivers might also need to give up their employment to provide essential care, further exacerbating economic burdens (18). To better cope, they not only seek strength from their spiritual beliefs but also strive to maintain social activities (21). The moderate phase of PD presents a multitude of challenges for their caregivers, such as the loss of freedom, communication difficulties, and changes in roles and relationships. They emphasize the importance of finding ways to foster autonomy, hope, and learning (22, 30, 36).

4 Discussion

This scoping review investigated data from 20 qualitative studies to identify knowledge gaps in understanding the needs and experiences of individuals with PD who received palliative care. In our research findings, we discovered that unmet emotional and informational support is a recurring theme mentioned by the majority of PD patients and their caregivers. PD patients and their caregivers face numerous emotional challenges. As the disease progresses, many PD patients may experience feelings of depression, anxiety, loneliness, and low self-esteem (38). These emotional challenges can impact their daily quality of life, social interactions, and overall health (39). As such, emotional support becomes an urgent need for them. Moreover, changes in family dynamics, financial pressures, loss of patient autonomy, and feelings of social isolation also contribute to the caregivers’ burdens (40). Thus, offering them emotional support is equally vital. While doctors and medical teams are the primary sources of information, communities, support groups, patient associations, and online communities can also provide invaluable resources for PD patients and caregivers (41, 42). Additionally, mental health professionals and social workers can offer them emotional support (43, 44).

Parkinson’s disease progression is gradual, usually starting with minor tremors and escalating to other symptoms that affect daily life (45). Since there is currently no cure for PD and each patient’s response is relatively unique, it complicates the prediction of disease progression and prognosis (46). Given the uncertainty around the cause of PD, coupled with the variability in its progression and the complexity of its treatment, patients and caregivers might have misconceptions about the disease (47). They might struggle to interpret their symptoms, be unsure about selecting the best treatment options, or be unaware of how to handle potential complications. Therefore, providing disease-related informational support is of paramount importance. PD patients and caregivers need to understand how to manage symptoms, adjust daily activities to accommodate the disease’s limitations, and effectively communicate with doctors and medical teams (48). Moreover, advanced PD patients might need more medications and more frequent medical check-ups (49). Patients with PD often have comorbidities such as diabetes or hypertension due to age-related factors. Research (50) has found that PD shares common pathogenic mechanisms with diabetes in inflammation, oxidative stress, etc. Additionally, the use of antihypertensive drugs may sometimes exacerbate PD symptoms (51). Given these needs, medical institutions and relevant organizations should consider initiating PD educational programs or home visits to help patients and caregivers better understand and cope with the disease (52, 53).

Effective coordination of care is an urgent need for PD patients and their caregivers. van Vliet et al. (54) believed that there are barriers between specialist palliative care and neurology. Furthermore, a qualitative study in the Netherlands involving healthcare professionals on palliative care for PD patients showed that some interviewees supported the development of a PD palliative care system. However, they also felt the need to better understand the essence of palliative care. Some interviewees stated they would never introduce the term “palliative” and believed doctors should not discuss spiritual issues with patients, arguing that medical care should remain the core focus (55). This highlights that many medical professionals still lack a clear understanding of palliative care, often confusing it with end-of-life care. Hence, training for medical and care staff in palliative care and team building should be enhanced to improve the palliative care experience for advanced Parkinson’s patients and their caregivers.

As the disease progresses, PD patients might experience a gradual decline in physical and cognitive functions, leading to increased difficulties in daily life. This uncertain future leaves many PD patients and their caregivers feeling overwhelmed and anxious about how to prepare for what is ahead (49). Planning for the future can help PD patients and caregivers better cope with the challenges the disease presents and ensure their needs and wishes are respected and met (56). ACP provides PD patients and caregivers with a tool and opportunity to prepare for the future and ensure their medical wishes are respected. While it may be an emotional challenge (57), it offers assurance to PD patients and caregivers that their wishes will be respected and executed in critical moments.

In this study, the theme of symptom management provided us with an opportunity to deeply understand the numerous challenges faced by PD patients and their caregivers. The progression of Parkinson’s disease brings about a series of symptoms that profoundly affect the daily lives of those affected. For instance, the loss of language and social interaction capabilities often leads to feelings of isolation and depression (18). Many patients find themselves compelled to abandon their professional roles, leading to financial pressures. When caregivers, typically family members, have to make the tough decision to give up their jobs to cater to the escalating needs of the patient, this financial burden intensifies (18). Our study’s findings reveal that caregivers’ coping mechanisms are multifaceted: many find solace and strength from their spiritual beliefs, while others emphasize the importance of maintaining social connections and activities to alleviate feelings of isolation and helplessness (21). In conclusion, symptom management in PD is a complex, multi-dimensional task. Patients must combat the physical manifestations of the disease while also dealing with psychological, social, and spiritual challenges. It is heartening to see that, in the face of these adversities, both patients and caregivers proactively seek various strategies and resources (36). Medical professionals should acknowledge the positive coping strategies of patients and caregivers and offer necessary assistance to meet their needs in symptom management.

5 Limitations

This review had several limitations. We only included English publications and did not undertake a hand search of significant journals. We also did not include gray literature. Given all of these considerations, it could be possible that some data sources were overlooked. Although we included literature from various countries, the lack of data from Southeast Asian countries may be strongly related to cultural factors and suggests that future research should further explore the current state of palliative care services in these countries. Lastly, we did not perform a quality assessment of all included studies since the risk of bias/quality assessment was not often suggested in the retrieved reviews.

6 Conclusion

This scoping review revealed critical knowledge gaps regarding the needs and experiences of PD patients and their caregivers who receive palliative care. Our findings indicate that many PD patients and caregivers often face unmet emotional and informational needs, and they deeply aspire for effective care coordination. As they plan for the future, they try to prepare, even though some are not well-versed with ACP. Furthermore, they bear a significant burden in symptom management. While some patients and caregivers have found coping mechanisms, the majority still wrestle with numerous challenges on psychological, social, and spiritual fronts. In conclusion, further research and promotion of effective strategies and resources are essential to better address these needs and enhance their quality of life.

Data availability statement

The original contributions presented in this study are included in the article/Supplementary material, further inquiries can be directed to the corresponding author.

Author contributions

YL: Methodology, Resources, Writing – original draft. YTL: Conceptualization, Data curation, Formal analysis, Software, Writing – review & editing. YC: Conceptualization, Supervision, Writing – review & editing.

Funding

The author(s) declare that no financial support was received for the research, authorship, and/or publication of this article.

Conflict of interest

The authors declare that the research was conducted in the absence of any commercial or financial relationships that could be construed as a potential conflict of interest.

Publisher’s note

All claims expressed in this article are solely those of the authors and do not necessarily represent those of their affiliated organizations, or those of the publisher, the editors and the reviewers. Any product that may be evaluated in this article, or claim that may be made by its manufacturer, is not guaranteed or endorsed by the publisher.

Supplementary material

The Supplementary Material for this article can be found online at: https://www.frontiersin.org/articles/10.3389/fmed.2024.1362828/full#supplementary-material

References

2. Armstrong M, Okun M. Diagnosis and treatment of Parkinson disease: A review. JAMA. (2020) 323:548–60.

3. Poewe W, Mahlknecht P. The clinical progression of Parkinson’s disease. Parkinson Relat Disord. (2009) 15:S28–32.

4. Varanese S, Birnbaum Z, Rossi R, Di Rocco A. Treatment of advanced Parkinson’s disease. Parkinsons Dis. (2010) 2010:480260.

5. Sepúlveda C, Marlin A, Yoshida T, Ullrich A. Palliative care: The world health organization’s global perspective. J Pain Symptom Manag. (2002) 24:91–6.

6. Senderovich H, Jimenez Lopez B. Integration of palliative care in Parkinson’s disease management. Curr Med Res Opin. (2021) 37:1745–59. doi: 10.1080/03007995.2021.1954895

7. Chen Y, Zhou W, Hou L, Zhang X, Wang Q, Gu J, et al. The subjective experience of family caregivers of people living with Parkinson’s disease: A meta-ethnography of qualitative literature. Aging Clin Exp Res. (2022) 34:959–70. doi: 10.1007/s40520-021-01995-9

8. Pedersen S, Suedmeyer M, Liu L, Domagk D, Forbes A, Bergmann L, et al. The role and structure of the multidisciplinary team in the management of advanced Parkinson’s disease with a focus on the use of levodopa-carbidopa intestinal gel. J Multidiscip Healthc. (2017) 10:13–27. doi: 10.2147/JMDH.S111369

9. Lum H, Kluger B. Palliative care for Parkinson disease. Clin Geriatr Med. (2020) 36:149–57. doi: 10.1016/j.cger.2019.09.013

10. Chan L, Yan O, Lee J, Lam W, Lin C, Auyeung M, et al. Effects of palliative care for progressive neurologic diseases: A systematic review and meta-analysis. J Am Med Dir Assoc. (2023) 24:171–84. doi: 10.1016/j.jamda.2022.11.001

11. Bock M, Katz M, Sillau S, Adjepong K, Yaffe K, Ayele R, et al. What’s in the sauce? The specific benefits of palliative care for Parkinson’s disease. J Pain Symptom Manag. (2022) 63:1031–40. doi: 10.1016/j.jpainsymman.2022.01.017

12. Sleeman K, Ho Y, Verne J, Glickman M, Silber E, Gao W, et al. Place of death, and its relation with underlying cause of death, in Parkinson’s disease, motor neurone disease, and multiple sclerosis: A population-based study. Palliat Med. (2013) 27:840–6. doi: 10.1177/0269216313490436

13. Klietz M, Tulke A, Müschen L, Paracka L, Schrader C, Dressler D, et al. Impaired quality of life and need for palliative care in a German cohort of advanced Parkinson’s disease Patients. Front Neurol. (2018) 9:120. doi: 10.3389/fneur.2018.00120

14. Jones R. Strength of evidence in qualitative research. J Clin Epidemiol. (2007) 60:321–3. doi: 10.1016/j.jclinepi.2006.06.001

15. Peters M, Godfrey C, McInerney P, Soares C, Khalil H, Parker D. The Joanna Briggs institute reviewers’ manual 2015: Methodology for JBI scoping reviews. Adelaide, SA: The Joanna Briggs Institute (2015).

16. Arksey H, O’Malley L. Scoping studies: Towards a methodological framework. Int J Soc Res Methodol. (2005) 8:19–32.

18. Hudson P, Toye C, Kristjanson L. Would people with Parkinson’s disease benefit from palliative care? Palliat Med. (2006) 20:87–94.

19. Giles S, Miyasaki J. Palliative stage Parkinson’s disease: Patient and family experiences of health-care services. Palliat Med. (2009) 23:120–5.

20. Hasson F, Kernohan W, McLaughlin M, Waldron M, McLaughlin D, Chambers H, et al. An exploration into the palliative and end-of-life experiences of carers of people with Parkinson’s disease. Palliat Med. (2010) 24:731–6.

21. Tan S, Williams A, Morris M. Experiences of caregivers of people with Parkinson’s disease in Singapore: A qualitative analysis. J Clin Nurs. (2012) 21:2235–46. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2702.2012.04146.x

22. Beaudet L, Ducharme F. Living with moderate-stage Parkinson disease: Intervention needs and preferences of elderly couples. J Neurosci Nurs. (2013) 45:88–95.

23. Seamark D, Blake S, Brearley S, Milligan C, Thomas C, Turner M, et al. Dying at home: A qualitative study of family carers’ views of support provided by GPs community staff. Br J Gen Pract. (2014) 64:e796–803. doi: 10.3399/bjgp14X682885

24. van Rumund A, Weerkamp N, Tissingh G, Zuidema S, Koopmans R, Munneke M, et al. Perspectives on Parkinson disease care in Dutch nursing homes. J Am Med Dir Assoc. (2014) 15:732–7. doi: 10.1016/j.jamda.2014.05.009

25. Murdock C, Cousins W, Kernohan W. “Running water won’t freeze”: How people with advanced Parkinson’s disease experience occupation. Palliat Support Care. (2015) 13:1363–72. doi: 10.1017/S1478951514001357

26. Fox S, Cashell A, Kernohan W, Lynch M, McGlade C, O’Brien T, et al. Palliative care for Parkinson’s disease: Patient and carer’s perspectives explored through qualitative interview. Palliat Med. (2017) 31:634–41.

27. Habermann B, Shin J. Preferences and concerns for care needs in advanced Parkinson’s disease: A qualitative study of couples. J Clin Nurs. (2017) 26:1650–6. doi: 10.1111/jocn.13565

28. Hurt C, Cleanthous S, Newman S. Further explorations of illness uncertainty: Carers’ experiences of Parkinson’s disease. Psychol Health. (2017) 32:549–66.

29. Lum H, Jordan S, Brungardt A, Ayele R, Katz M, Miyasaki J, et al. Framing advance care planning in Parkinson disease: Patient and care partner perspectives. Neurology. (2019) 92:e2571–9. doi: 10.1212/WNL.0000000000007552

30. Maffoni M, Pierobon A, Frazzitta G, Callegari S, Giardini A. Living with Parkinson’s–past, present and future: A qualitative study of the subjective perspective. Br J Nurs. (2019) 28:764–71.

31. Lennaerts-Kats H, Ebenau A, Steppe M, van der Steen J, Meinders M, Vissers K, et al. How long can i carry on?” The need for palliative care in Parkinson’s disease: A qualitative study from the perspective of bereaved family caregivers. J Parkinsons Dis. (2020) 10:1631–42. doi: 10.3233/JPD-191884

32. Prizer L, Gay J, Wilson M, Emerson K, Glass A, Miyasaki J, et al. A mixed-methods approach to understanding the palliative needs of Parkinson’s patients. J Appl Gerontol. (2020) 39:834–45.

33. Kurpershoek E, Hillen M, Medendorp N, de Bie R, de Visser M, Dijk J. Advanced care planning in Parkinson’s disease: In-depth interviews with patients on experiences and needs. Front Neurol. (2021) 12:683094. doi: 10.3389/fneur.2021.683094

34. Rosqvist K, Kylberg M, Löfqvist C, Schrag A, Odin P, Iwarsson S. Perspectives on care for late-stage Parkinson’s disease. Parkinsons Dis. (2021) 2021:9475026.

35. Churm D, Dickinson C, Robinson L, Paes P, Cronin T, Walker R. Understanding how people with Parkinson’s disease and their relatives approach advance care planning. Eur Geriatr Med. (2022) 13:109–17.

36. Kwok J, Lee J, Auyeung M, Chan M, Chan H. Letting nature take its course: A qualitative exploration of the illness and adjustment experiences of Hong Kong Chinese people with Parkinson’s disease. Health Soc Care Commun. (2020) 28:2343–51. doi: 10.1111/hsc.13055

37. Hurt C, Rixon L, Chaudhuri K, Moss-Morris R, Samuel M, Brown R. Identifying barriers to help-seeking for non-motor symptoms in people with Parkinson’s disease. J Health Psychol. (2019) 24:561–71. doi: 10.1177/1359105316683239

38. Landau S, Harris V, Burn D, Hindle J, Hurt C, Samuel M, et al. Anxiety and anxious-depression in Parkinson’s disease over a 4-year period: A latent transition analysis. Psychol Med. (2016) 46:657–67. doi: 10.1017/S0033291715002196

39. Quelhas R, Costa M. Anxiety, depression, and quality of life in Parkinson’s disease. J Neuropsychiatry Clin Neurosci. (2009) 21:413–9. doi: 10.1176/jnp.2009.21.4.413

40. Van der Steen J, Lennaerts H, Hommel D, Augustijn B, Groot M, Hasselaar J, et al. Dementia and Parkinson’s disease: Similar and divergent challenges in providing palliative care. Front Neurol. (2019) 10:54. doi: 10.3389/fneur.2019.00054

41. Attard A, Coulson NS. A thematic analysis of patient communication in Parkinson’s disease online support group discussion forums. Comp Hum Behav. (2012) 28:500–6.

42. Shah S, Glenn G, Hummel E, Hamilton J, Martine R, Duda J, et al. Caregiver tele-support group for Parkinson’s disease: A pilot study. Geriatr Nurs. (2015) 36:207–11. doi: 10.1016/j.gerinurse.2015.02.002

43. Erickson C, Muramatsu N. Parkinson’s disease, depression and medication adherence: Current knowledge and social work practice. J Gerontol Soc Work. (2004) 42:3–18.

44. Troeung L, Gasson N, Egan S. Patterns and predictors of mental health service utilization in people with Parkinson’s disease. J Geriatr Psychiatry Neurol. (2015) 28:12–8.

45. Poewe W. The natural history of Parkinson’s disease. J Neurol. (2006) 253(Suppl. 7):Vii2–6. doi: 10.1007/s00415-006-7002-7

46. Zahoor I, Shafi A, Haq E. Pharmacological treatment of Parkinson’s disease. In: Stoker T, Greenland J editors. Parkinson’s disease: Pathogenesis and clinical aspects. Brisbane, QL: Codon Publications (2018).

47. Salinas M, Chambers E, Ho T, Khemani P, Olson D, Stutzman S, et al. Patient perceptions and knowledge of Parkinson’s disease and treatment (KnowPD). Clin Park Relat Disord. (2020) 3:100038. doi: 10.1016/j.prdoa.2020.100038

48. Kessler D, Liddy C. Self-management support programs for persons with Parkinson’s disease: An integrative review. Patient Educ Couns. (2017) 100:1787–95. doi: 10.1016/j.pec.2017.04.011

49. Haahr A, Kirkevold M, Hall E, Ostergaard K. Living with advanced Parkinson’s disease: A constant struggle with unpredictability. J Adv Nurs. (2011) 67:408–17. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2648.2010.05459.x

50. Patil R, Tupe R. Communal interaction of glycation and gut microbes in diabetes mellitus, Alzheimer’s disease, and Parkinson’s disease pathogenesis. Med Res Rev. (2024) 44:365–405. doi: 10.1002/med.21987

51. Kutikuppala L, Sharma S, Chavan M, Rangari G, Misra A, Innamuri S, et al. Bromocriptine: Does this drug of Parkinson’s disease have a role in managing cardiovascular diseases? Ann Med Surg. (2024) 86:926–9.

52. Gatsios D, Antonini A, Gentile G, Konitsiotis S, Fotiadis D, Nixina I, et al. Education on palliative care for Parkinson patients: Development of the “Best care for people with late-stage Parkinson’s disease” curriculum toolkit. BMC Med Educ. (2021) 21:538. doi: 10.1186/s12909-021-02964-6

53. Fleisher J, Barbosa W, Sweeney M, Oyler S, Lemen A, Fazl A, et al. Interdisciplinary home visits for individuals with advanced Parkinson’s disease and related disorders. J Am Geriatr Soc. (2018) 66:1226–32. doi: 10.1111/jgs.15337

54. van Vliet L, Gao W, DiFrancesco D, Crosby V, Wilcock A, Byrne A, et al. How integrated are neurology and palliative care services? Results of a multicentre mapping exercise. BMC Neurol. (2016) 16:63. doi: 10.1186/s12883-016-0583-6

55. Lennaerts H, Steppe M, Munneke M, Meinders M, van der Steen J, Van den Brand M, et al. Palliative care for persons with Parkinson’s disease: A qualitative study on the experiences of health care professionals. BMC Palliat Care. (2019) 18:53. doi: 10.1186/s12904-019-0441-6

56. Jordan S, Kluger B, Ayele R, Brungardt A, Hall A, Jones J, et al. Optimizing future planning in Parkinson disease: Suggestions for a comprehensive roadmap from patients and care partners. Ann Palliat Med. (2020) 9(Suppl 1):S63–74. doi: 10.21037/apm.2019.09.10

57. Sokol L, Young M, Paparian J, Kluger B, Lum H, Besbris J, et al. Advance care planning in Parkinson’s disease: Ethical challenges and future directions. NPJ Parkinsons Dis. (2019) 5:24. doi: 10.1038/s41531-019-0098-0

Keywords: palliative care, Parkinson’s disease, needs, experiences, scoping review

Citation: Lou Y, Li Y and Chen Y (2024) The palliative care needs and experiences of patients with advanced Parkinson’s disease: a qualitative scoping review. Front. Med. 11:1362828. doi: 10.3389/fmed.2024.1362828

Received: 01 February 2024; Accepted: 26 March 2024;

Published: 10 April 2024.

Edited by:

Grazia Daniela Femminella, University of Naples Federico II, ItalyReviewed by:

Klara Komici, University of Molise, ItalyLuca Marino, Sapienza University of Rome, Italy

Copyright © 2024 Lou, Li and Chen. This is an open-access article distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution License (CC BY). The use, distribution or reproduction in other forums is permitted, provided the original author(s) and the copyright owner(s) are credited and that the original publication in this journal is cited, in accordance with accepted academic practice. No use, distribution or reproduction is permitted which does not comply with these terms.

*Correspondence: Yiping Chen, yipingchen520@126.com

†ORCID: Yan Lou, orcid.org/0000-0002-7302-5132

Yan Lou

Yan Lou Yiting Li3

Yiting Li3  Yiping Chen

Yiping Chen