Nexus between uncertainty, remittances, and households consumption: Evidence from dynamic SUR application

- 1Agricultural Bank of China LTD Nanjing Chengbei Sub-branch, Nanjing, Jiangsu, China

- 2School of Business and Economics, United International University, Dhaka, Bangladesh

- 3School of Political Science and Economics, Waseda University, Tokyo, Japan

- 4Hailey College of Banking and Finance, University of the Punjab, Lahore, Pakistan

- 5Hailey College of Banking and Finance, University of the Punjab, Lahore, Pakistan

- 6Department of Economics, Aligarh Muslim University, Aligarh, India

Household consumption induces aggregated economic activities by pushing market demand, capital accumulation and financial growth in the economy; on the other hand, instability in household consumption adversely affects the overall economic progress. Thus, exploring the key determinants responsible for household consumption instability is essential. The motivation of the study is to gauge the role of pandemic uncertainties and remittance inflow on household consumption in lower, Lower-middle, and Upper-Middle-income Countries for the period 1996 to 2020. The study employed several econometrical tools, including a panel cointegration test with the error correction term, dynamic SUR. The panel unit root test following CADF and CIPS documented variables are stationary after the first difference, and long-run associations are confirmed with the panel cointegration test. The coefficient of Dynamic Seemingly Unrelated Regression exposed pandemic uncertainties and has a negative impact on household consumption in all three-panel estimations; however, the coefficient of PUI is more prominent with COVID-19 effects. Remittances’ role in household consumption was positive and statistically significant, suggesting migrant remittances encourage additional consumption among households. On the policy aspect, the study proposed that the government should undertake macro policies to manage policy uncertainties so that the normal course of consumption level should not be interrupted because household consumption volatility creates discomfort in aggregated development. Moreover, efficient reallocation and remittance channels should be ensured in the economy; therefore, efficient institutional development has to be confirmed.

Introduction

Household consumption, according to the Keynesian macro-economic model, plays a critical and deterministic role in ensuring economic growth with the extension of capital formulation, aggregated output escalation and elevation of aggregated expenditure in the economy. The impact of household consumption can also be discovered in financial development, poverty reduction, trade liberalization, and foreign capital flows. Thus, policymakers always seek an appropriate policy (monetary and fiscal policy) to encourage household expenditures. Furthermore, a growing number of researchers in literature have investigated the key determinants and revealed several macro and micro fundamentals. According to the existing literature, household consumption is influenced by several variables. Among those remittances, inflows have been placed on the apex. Literature suggested that remittance inflows contribute to household consumption levels by lessening income variability, security, and liquidity. The study by Adams, Lopez-Feldman (Adams, 2008) documented that households’ spending behavior differs among households who received remittances and who did not.

With this study, we considered pandemic uncertainties, remittances and household nexus in the panel data estimation for lower, lower-middle and Upper-Middle-Income Countries with and without potential effects from COVID-19. In December 2019, the coronavirus (COVID-19) outbreak gained extensive media attention (Qamruzzaman, 2018; Qamruzzaman et al., 2019a; Qamruzzaman et al., 2019b; Haroon and Rizvi, 2020) and prompted widespread anxiety (Ali et al., 2020), virtually closing down most of the economy. When a virus spreads, several elements determine its economic impact, including the immediate impacts of containment attempts to control it; the duration of these containment efforts; and the amount to which direct economic implications endure, amplify, and spread across regions. Since the direct impacts of solitary confinement have been thoroughly explored elsewhere, our model does not mention them. It is worthwhile to utilize when it is more accurate than projections based on mechanically adding up the expenses of shutting down various sectors of the economy. Furthermore, as seen by widespread lockdowns and restrictions to prevent new infections, the outbreak has had a significant effect on the economic slowdown, unemployment (Uddin and Alam, 2021; Azam et al., 2022), The motivation of this study is to seek the impact of uncertainties and emittances on household consumption with the inclusion and exclusion of covid effects in empirical estimation. The study has taken into account three panels of data which are sub-grouped according to income level that is lower-income countries (LIC), Lower-middle income countries (LMIC) and Upper-Middle-Income Countries (UMIC), respectively, for the period 1996–2020. The empirical estimation has been executed by implementing several econometrical tools, including the homogeneity test, cross-sectional dependency and panel unit root test. The magnfititutes of pandemic uncertainties and remittances on household consumption has detected by performing dynamic SUR. The elasticity of pandemic uncertain tie has documented a negative and statistically significant connection to household consumption, whereas remittances support increasing household consumption by ensuring income stability and preferred liquidity.

The present study contributes to the existing literature in two folds. First, the nexus between pandemic uncertainties and household consumption with the inclusion of COVID-19 effects, for the first-ever empirical assessment as far as the existing literature is concerned. According to existing literature, a negligible number of researcher has investigated the impact of uncertainties on household consumption, while referring to pandemic uncertainties’ effects on household consumption has yet to be extensively investigated. The present study intends to explore the existing literature by exploring fresh insights and establishing a bridge to mitigate the research gap. Furthermore, assessing the impact of pandemic uncertainties study has implemented an empirical model assessment to include and exclude the COVID-19 economic phenomenon. Second, the impact of uncertainties on macro fundamentals has been investigated. However, the effects of pandemic uncertainties on household consumption have yet to assess extensively. This study tried to explore fresh insight relating to the nexus between pandemic uncertainties and household consumption. Third, it is well established that remittances significantly impact a household’s consumption and support stability. However, the role of remittance on household consumption with pandemic uncertainties has yet to investigate extensively. The present study has contributed to mitigating the research gap.

The remaining structure of the paper is as follows: Introduction deals with the relevant literature survey pertinent to the present study. The variables definition and methodology of the study are reported in Introduction. Data analysis and interpretation are exhibited in Introduction. Finally, the conclusion of the study is reported in Introduction.

Theoretical model

The motivation of the study is to explore the household’s consumption trend due to economic policy uncertainty and pandemic-related uncertainty for the period 1996–2020. The following theoretical model has been established by following the income-expenditure relationship in an open economy (see, for instance, Wu (Wu, 2020), (Coddington, 1976; Karim and Qamruzzaman, 2020; Qamruzzaman, 2020; Qamruzzaman and JIANGUO, 2020; Jia et al., 2021; Lingyan et al., 2021; QAMRUZZAMAN et al., 2021)). The generalized I-E economic relationship cab is reported as follows:

Household consumption (C) can be derived by subsuming the trade balance in Eq 1 with (X-M). Therefore,

Furthermore, it is believed that during uncertainties, the aggregated output in the economy is adversely affected, the money flows from foreign remittances positively increase in securing households’ financial security, and pandemic uncertainties have adverse effects on domestic trade expansion, that is, the trade balance will be experienced negative trend which eventually decreases overall consumption in the economy. By subsuming the focused variables in Eq 2, the empirical model can be rewritten in the following manner.

Noted that FD stands for financial development role in the theoretical model.

Literature survey

Uncertainty and household consumption

Economic uncertainty in the global economy during the COVID-19 Pandemic, according to Altig, Baker (Altig et al., 2020), is greater than before the COVID-19 Pandemic. According to Baker, Bloom (Baker et al., 2020a), COVID-19 Pandemic-related economic uncertainty has a considerable impact on macroeconomic variables (consumption, employment, and investments) and is adversely associated with stock market returns. According to Leduc and Liu (Leduc and Liu, 2020), COVID-19-related uncertainty is a substantial driver of macroeconomic indices. Following these articles, we concentrate on Ahir, Bloom (Ahir et al., 2750) Pandemic Uncertainty Index for measuring pandemic-related. Wu and Zhao (Wu and Zhao, 2021) have investigated household consumption behavior during economic uncertainty using Chinese household consumption data. The study documented that EPU has negative effects on liquidity position that household prefers to hold more liquid assets such as cash or cash equivalent by subsidizing their present level of consumption.

The COVID-19 Pandemic has had a detrimental impact on many aspects of the global economy. Governments have enacted several policy consequences to restrict the spread of the new coronavirus, which is more lethal than the virus that causes normal flu. During the COVID-19 Pandemic, governments have locked down public locations such as schools, restaurants, and shopping malls, or individuals willingly remain at home. (Fetzer et al., 2020; Ganlin et al., 2021; Pu et al., 2021; QAMRUZZAMAN et al., 2021; Xu et al., 2021; Yang et al., 2021). In the study, Guo, Liao (Guo et al., 2021) documented with survey data in China that the outbreak of COVID-19 produces tremendous concern among households in making consumption decisions, especially in managing their liquidity position. Laborde, Martin (Laborde et al., 2020) revealed that the COVID pandemic had challenged food security by raising concerns about global agricultural production disruption. Food prices rose almost immediately, and as a result, there has been substantial concern that poverty and food insecurity will rise, and the nutritional status of vulnerable groups will fall, as the pandemic continues.

Wu (Wu, 2020) has gauged the nexus between pandemic-related uncertainties and household consumption from 1996-to 2017 with a panel of 138 countries employing feasible generalized least squares (FGLS). Household consumption is adversely affected by gross fixed capital creation, government spending, balance of trade, and the Pandemic Uncertainty Index, according to the theoretical model and empirical data from the Feasible Generalized Least Squares (FGLS) estimates. The findings are also true in the panel dataset, including 42 high-income nations and 96 developing economies. Liu, Pan (Liu et al., 2020) investigated the nexus between mobile banking, pandemic uncertainties and household consumption in China by capitalizing on the micro-level data extracted from china household finance survey data (CHFS). Study findings documented that during the COVID outbreak, the household consumption level declined in rural and urban areas. Mobile banking facilitates augmented household consumption in urban areas but remains unaffected in rural areas. The study further postulated that mobile payment systems, in particular, may help consumers and organizations migrate from offline to online consumption, overcoming space and time constraints, avoiding wasteful staff mobility, and addressing consumer and corporate demands throughout the epidemic. Mobile payment is important in increasing consumption; nevertheless, it is only seen in metropolitan households. Li, Song (Li et al., 2020) revealed that pandemic uncertainties significantly impact household consumption and liquidity constraints. The study also documented that the propensity of savings willingness has increased with limiting liquidity constraints due to COVID-19 outbreaks. For tourism development, Işık, Sirakaya-Turk (Işık et al., 2020) has evaluate the effects of EPU on tourism development, study revealed that adverse association between EPU and tourism development, implying that increase of uncertainties in the economy decrease the arrival of international tourist in the economy.

Remittance and household consumption

The current economic crisis has prompted policymakers and economists to reconsider economic stabilization mechanisms. One of the most severe effects of production shocks is household consumption unpredictability, which harms the welfare of risk-averse agents. Household consumption uncertainty, according to Athanasoulis and Van Wincoop (Athanasoulis and Van Wincoop, 2000) and Pallage and Robe (Pallage and Robe, 2003), might have negative effects on the buildup of human and physical capital. The determinants of household consumption instability include financial security, financial development, economic progress, and macro diversification. In contrast, many researchers have investigated the key determinants in stabilizing household consumption and established that excess money and financial security could mitigate the adversity of household consumption (Hossain and Gani, 2022; JinRu and Qamruzzaman, 2022; Karim et al., 2022; Zhao and Qamruzzaman, 2022). Remittance inflows have emerged and placed in a position to ensure stability in income elasticity, especially in the volatile macroeconomic state.

Moreover, migration is predicted to improve household income and consumption via remittances, including cash and products sent by migrants to family members remaining in the place of origin. The study of Debnath and Nayak (Debnath and Nayak, 2022) addressed the impact of remittances on household consumption by taking a sample of 785 migrants remittances recipients located in a frequently drought-affected Bankura district in the Rarh region of West Bengal State of India. Logistic regression model estimation documented that households preferred remittance to maintain food costs and repay their debt obligation. Moreover, the study established remittances’ role in eradicating chronic poverty and relieving the rural population from the vicious cycle of poverty by offering income liquidity and financial security. In Adams and Cuecuecha (Adams and Cuecuecha, 2010), a two-stage multinomial selection model was used to analyze household survey data collected in Guatemala in 2002. The study discovered that households receiving international remittances spend less on food expenses, and those receiving either internal or international remittances spend more on education and housing than they would have otherwise. A similar vine of evidence is available in the study of Adams, Lopez-Feldman (Adams, 2008) and Wouterse (Wouterse, 2008).

Remittance’s role in reducing household consumption instability has investigated and documented the critical role that the inflows of remittances bring households consumption stability by ensuring financial security and liquidity (Combes and Ebeke, 2011; Mehta et al., 2022; Serfraz et al., 2022). This effect may be examined via changes in household migration status and consumer purchasing patterns (To et al., 2017), which is critical for determining whether migrant remittances contribute to household welfare enhancement. Additionally, if remittances are utilized to cover health and education costs, they help ensure the long-term development of human capital (Nguyen et al., 2017; Alam et al., 2020).

Limitations in the existing literature

After careful assessment of the existing literature, we have found the following limitations.

1. The impact of uncertainties on macro fundamentals has been investigated; however, the effects of pandemic uncertainties on household consumption have yet to assess extensively. This study tried to explore fresh insight relating to the nexus between pandemic uncertainties and household consumption.

2. It is well established that remittances significantly impact households’ consumption and support stability. However, the role of remittance on household consumption with pandemic uncertainties has yet to investigate extensively. The present study has contributed to mitigating the research gap.

Data and empirical estimation procedure

Model specification

By taking into account the motivation of the study, the generalized empirical equation can be displayed in the following manner;

Where

As a dependent variable, household consumption is measured by final household consumption (constant 2015 US$) and remittances inflows are measured by Personal remittances received (current US$). Ahir, Bloom (Ahir et al., 2750) first proposed the Pandemic Uncertainty Index (PUI). This new dataset tracks national-level conversations regarding pandemics. The PUI is computed by measuring the number of words in Economist Intelligence Unit (EIU) national reports that refer to pandemic uncertainty (and its variations). Note that a higher index value suggests higher uncertainty about pandemics. Apart from target variables, two additional variables are considered in empirical estimation: financial development and government expenditure. According to existing literature, financial benefits availability and investment opportunity in the financial system allows households financial mobility and liquidity, which eventually encourages consumer spending behavior. On the other hand, government spending injects money into the economy, allowing households greater scope for income accumulation. Therefore, the inclusion of financial development and government spending might have the capacity to produce diverse outcomes from empirical assessment.

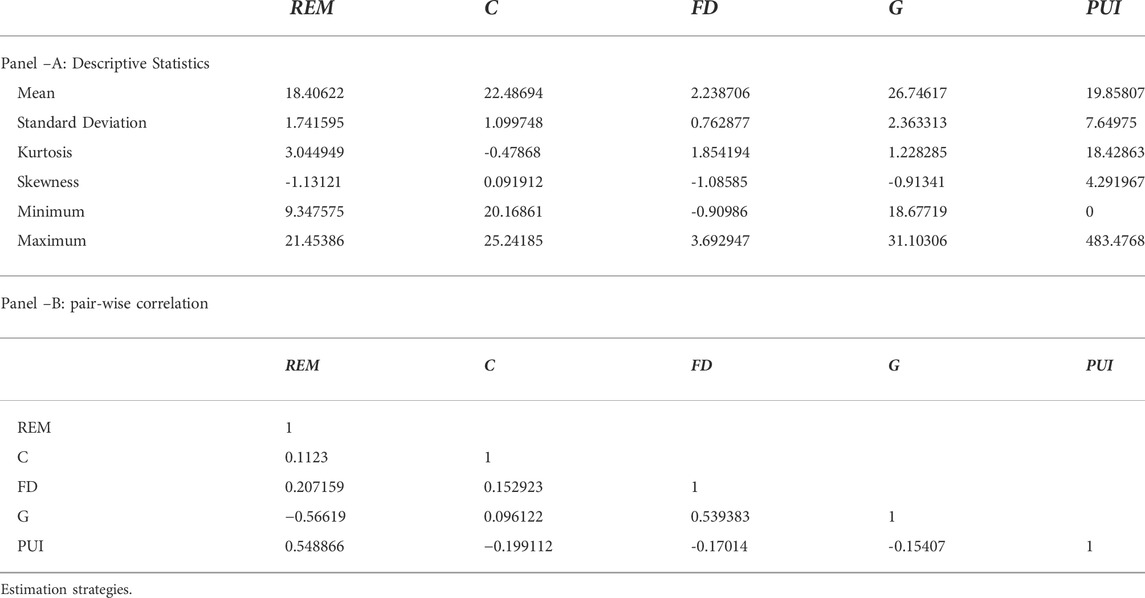

The descriptive statistics of research variables display in Table 1 include panel A for descriptive statistics and the pairwise correlation matrix in Panel–B. The mean value of REM is 18.406 with a standard deviation of 1.741, indicating the range of remittances inflows of 15.671–20.014. Moreover, the minimum level of remittances is 9.347, and the maximum level of remittances is 21.453. The average household’s consumption level is 22.4869, and the standard deviation is 1.099, implying the household consumption level ranges from 19.994 to 23.512. The minimum value of C is20.168, and the maximum is 25.24. The mean value of the pandemic uncertainties index is 19.85807, and the standard deviation is 7.64975, indicating the PUI range of 12.214–27.457.

According to pairwise correlation output, a positive correlation between remittances inflows and pandemic uncertainties is apparent, suggesting the migrant population has sent more money to their home country to ensure their financing security. Household consumption and PUI revealed a negative association which is expected. It implies that uncertainties discourage households from spending money on second-category demand. Furthermore, remittance inflows cause household consumption on a positive note. Excess capital flows to households allow them to maintain their present level of consumption even in a state of uncertainty.

The motivation of the study is to investigate the nexus between pandemic uncertainties, remittances and household consumption from 1996 to 2020. The study implemented Dynamic Seemingly Unrelated Regression (DSUR), which was proposed by Mark, Ogaki (Mark et al., 2005), for detecting the impact of pandemic uncertainties, remittances, financial development and gross capital formation on households consumption in LIC, LMIC, and UMIC countries. The DSUR method is practicable for panels where the number of cointegrating regression equations N is much less than the number of time-series data T. furthermore, heterogeneous sets of regressors are included in the regressions, as well as when equilibrium errors are linked via cointegration regressions, the DSUR outperforms non-system techniques such as dynamic ordinary least square (DOLS) and provides efficiency gains over these methods. Another benefit of the DSUR is that it may be used when the panel is heterogeneous or homogenous, as previously stated (Hongxing et al., 2021). The DSUR is as follows:

Where

Apart from the key target model, the study has implemented several data properties assessment tests by employing widely applied panel data tests, including research units heterogeneity tests by following the framework offered by Pesaran and Yamagata (Pesaran and Yamagata, 2008). The internal interdependency among research variables has been assessed by employing the test of cross-sectional dependency following Pesaran, Ullah (Pesaran et al., 2008), Pesaran (Pesaran, 2004). Panel stationary tests have been implemented for diagnosing the variables stationarity test following Pesaran (Pesaran, 2007), which can handle the cross-sectional dependency among research units.

Empirical results and discussion

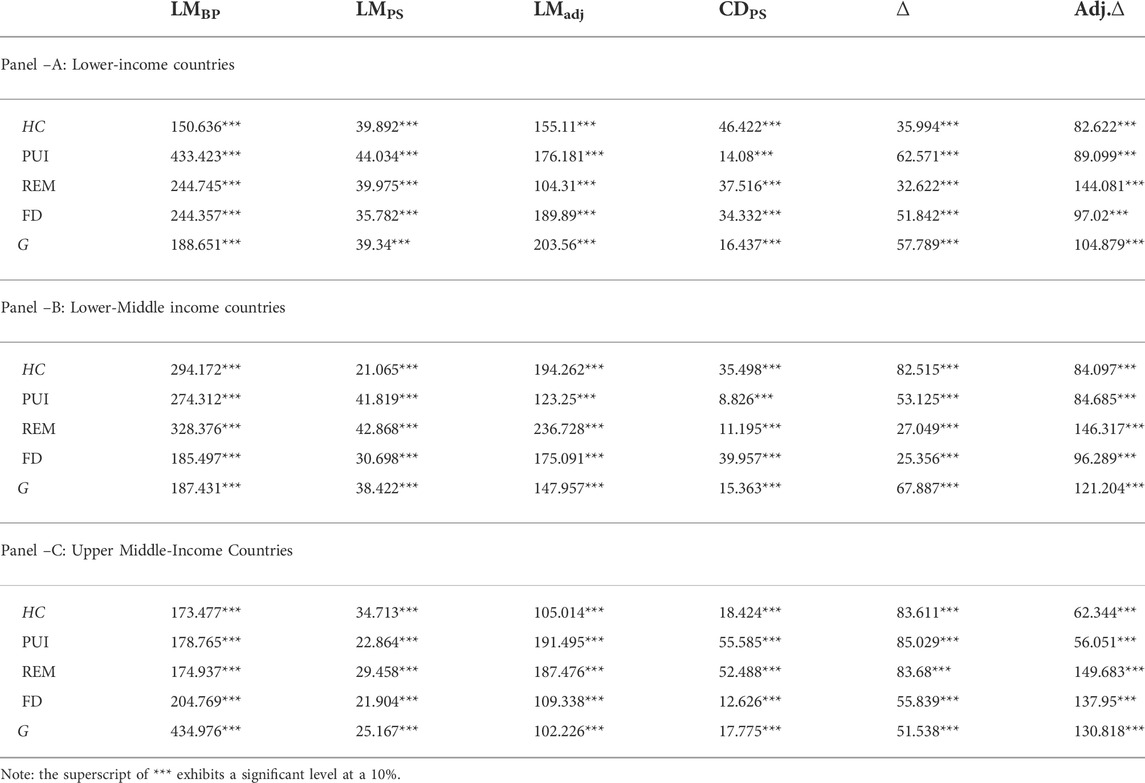

Before implementing the target model, the study possessed several elementary assessments such as cross-sectionally dependent tests, tests of heterogeneity, unit root test, and cointegration test. Table 2 exhibits the cross-sectional dependency test results with the cross-sectionally independent null hypothesis. Regarding the test statistics and associated p-value from the CSD test, study findings suggest rejecting the null hypothesis, alternatively confirming the common dynamics among research units. Furthermore, the homogeneity test results documented heterogeneous proprieties in the research unit in all three data panels.

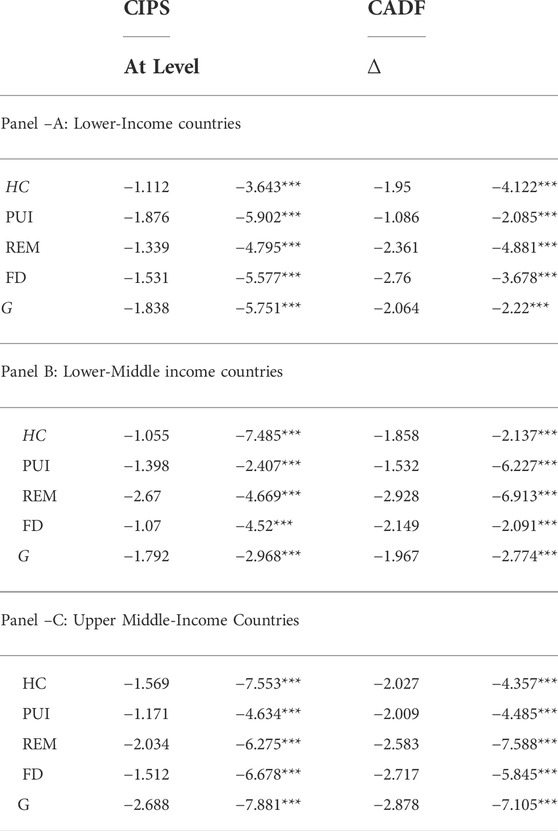

Following, Study deals with panel unit root tests by employing cross-sectionally dependent test of stationary, offered by Pesaran (Pesaran, 2007), commonly known as CIPS and CADF. The panel unit root test results in Table 3 include panel-A for LIC, Panel-B for LIMC and Panel–C for UMIC. According to the test statistics of panel unit root tests, it is apparent that all the variables are stationary after the first difference.

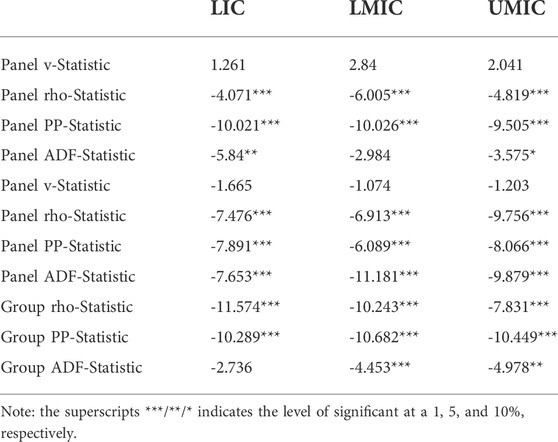

The long-run association study has implemented the panel cointegration test by following Pedroni (Pedroni, 2004), Pedroni (Pedroni, 2001), and Table 4 exhibits the cointegration test results. Refers to test statistics, it is apparent that most test statistics are statistically significant at a 1% level of significance, suggesting the rejection of the null hypothesis that on-cointegration. Alternatively, the study established a long-run association between pandemic uncertainties, household consumption, remittances inflows, and financial inclusion in all three panels.

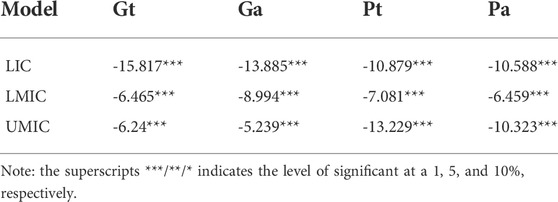

Nest’s study further implemented with advanced panel cointegration test by following Westerlund (Westerlund, 2007) with the null hypothesis of no-cointegration. Gt, Ga, Pt, and Pa test statistics were statistically significant at a 1% significance level, suggesting the long-run association in the empirical equation (see Table 5).

Dynamic Seemingly uncorrelated Regression

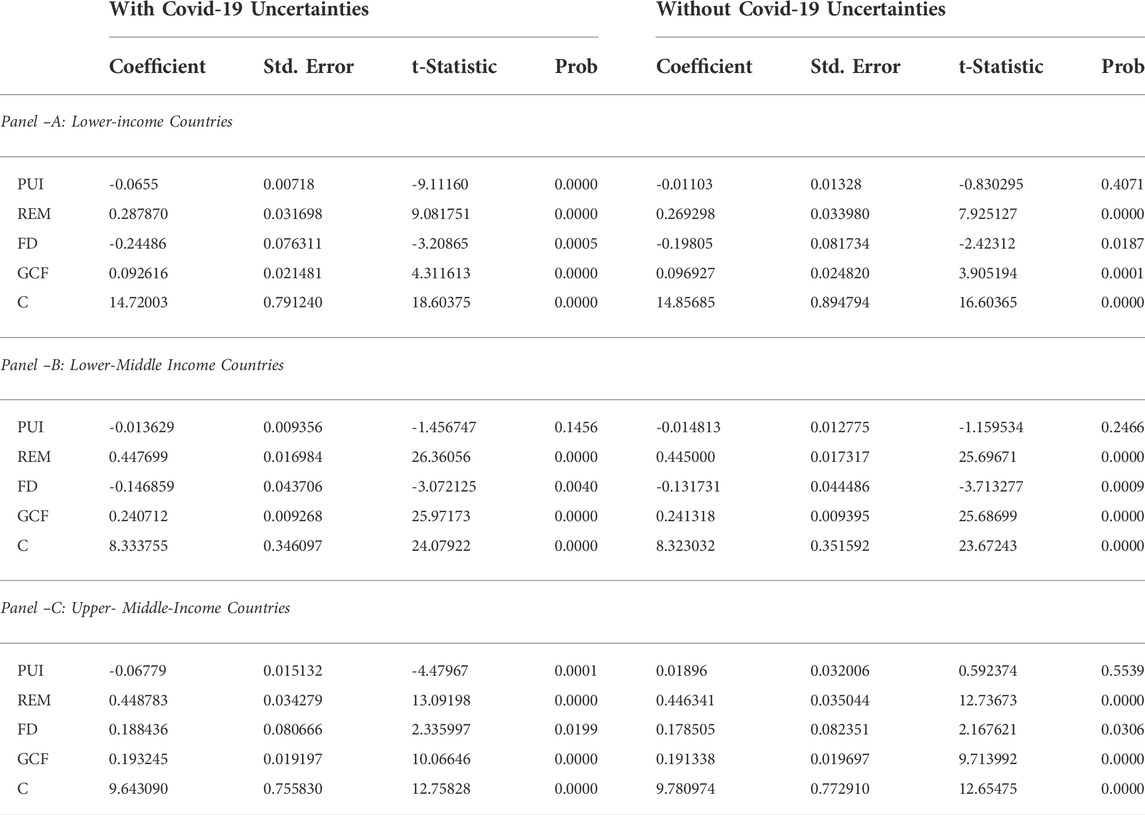

The following study performed dynamic SUR in exploring the coefficients of independent variables that are Pandemic Uncertainty Index (PUI), remittance (REM), gross capital formation (GCF), and financial development (FD) household consumption in LIC, LMIC, and UMIC. The results of the empirical estimation are displayed in Table 6.

Refers to the impact of pandemic uncertainties on household consumption, the study documented negative and statistically significant linkage in LIC (a coefficient of -0.0655), LMIC (a coefficient of -0.01362), and UMIC (a coefficient of -0.06779). In particular, a 10% increase in pandemic uncertainties can decrease household consumption by 0.655% in LIC, 0.1362% in LMIC, and 0.677% in UMIC, respectively. Our study findings are in line with existing literature see Chen, Qian (Chen et al., 2021), Wu (Wu, 2020), ACMA (ACMA, 2014), Li and Qamruzzaman (Li and Qamruzzaman, 2022), Baker, Farrokhnia (Baker et al., 2020b). The possible explanation regarding household consumption variability is the fare of unavoidable consequences due to economic uncertainties. To maintain the normal course of life, households should have to maintain financial and food security with sufficient money flows; therefore, during the pandemic, they become more cautious in their present consumption trend. In the study of Coibion, Gorodnichenko (Coibion et al., 2020), the authors postulated that pandemic uncertainties discourage households’ spending behavior and increase negative perception in recovering the economic adversity due to unforeseen causes. Furthermore, refers to output derived in Model-2 (without covid-19 uncertainties). The study documented a negative and statistically significant connection between pandemic uncertainties and household consumption in all three panel estimates. More specifically, a 10% increase of uncertainties due to non-human causing events in the economy can result in an adverse impact on household consumption that is level of consumption to be decreased by 0.1103% in LIC, 0.148% in LMIC, and 0.189% in UMIC, respectively. With a comparison note, it is obvious from the magnitude of PUI on HC that in both cases household consumption has adversely affected by the empirical model estimation with COViD-19 has produced more prominent scratch on households mind in compare to the past events.

The study documented a positive and statistically significant linkage between remittances inflows and household consumption in LIC (a coefficient of 0.2878), LMIC (a coefficient of 0.4476) and UMIC (a coefficient of 0.4487). The existing literature supports our study findings see Combes and Ebeke (Combes and Ebeke, 2011), Mondal and Khanam (Mondal and Khanam, 2018). In particular, a 10% development in remittance inflows can positively affect household consumption by 2.876% in LIC, 4.476% in LMIC, and 4.487% in UMIC. The possible reasons that induce household consumption with excess liquidity are migrant’s injection of money inflows into the economy. Additional money inflows into the economy, especially in the hands of households, increase their purchasing capacity and allow them to think about additional consumption over certain levels of savings (Adams, 2006; Faruqui et al., 2015; Jianguo and Qamruzzaman, 2017; Jia et al., 2020; Ganlin et al., 2021; Andriamahery and Qamruzzaman, 2022a; Andriamahery and Qamruzzaman, 2022b). Therefore additional expenditure for consumption is an inhabitable outcome with money availability.

The study documented a negative and statistically significant linkage between financial development and household consumption in LIC (a coefficient of 0.2445) and LMIC (a coefficient of -0.1468). The study suggests that access to formal financial services and benefits increases savings propensity among households, and thus by subsidizing extravagant consumption, households prefer to save for future consumption. However, household consumption level in Upper-Income Countries has increased with the development of the financial sector (a coefficient of 0.1884), suggesting that opportunities for generating a higher income level with financing and investing opportunities in the economy induce households to expand their present consumption level. The possible motivation behind this rational behavior is that earning opportunities establish financial securities and liquidity; therefore, extra consumption can be managed; a study by Song, Li (Song et al., 2020) established that access to formal financial services and financial services digitalization promotes households consumption levels and the impacts are more prominent in an urban area than a rural area.

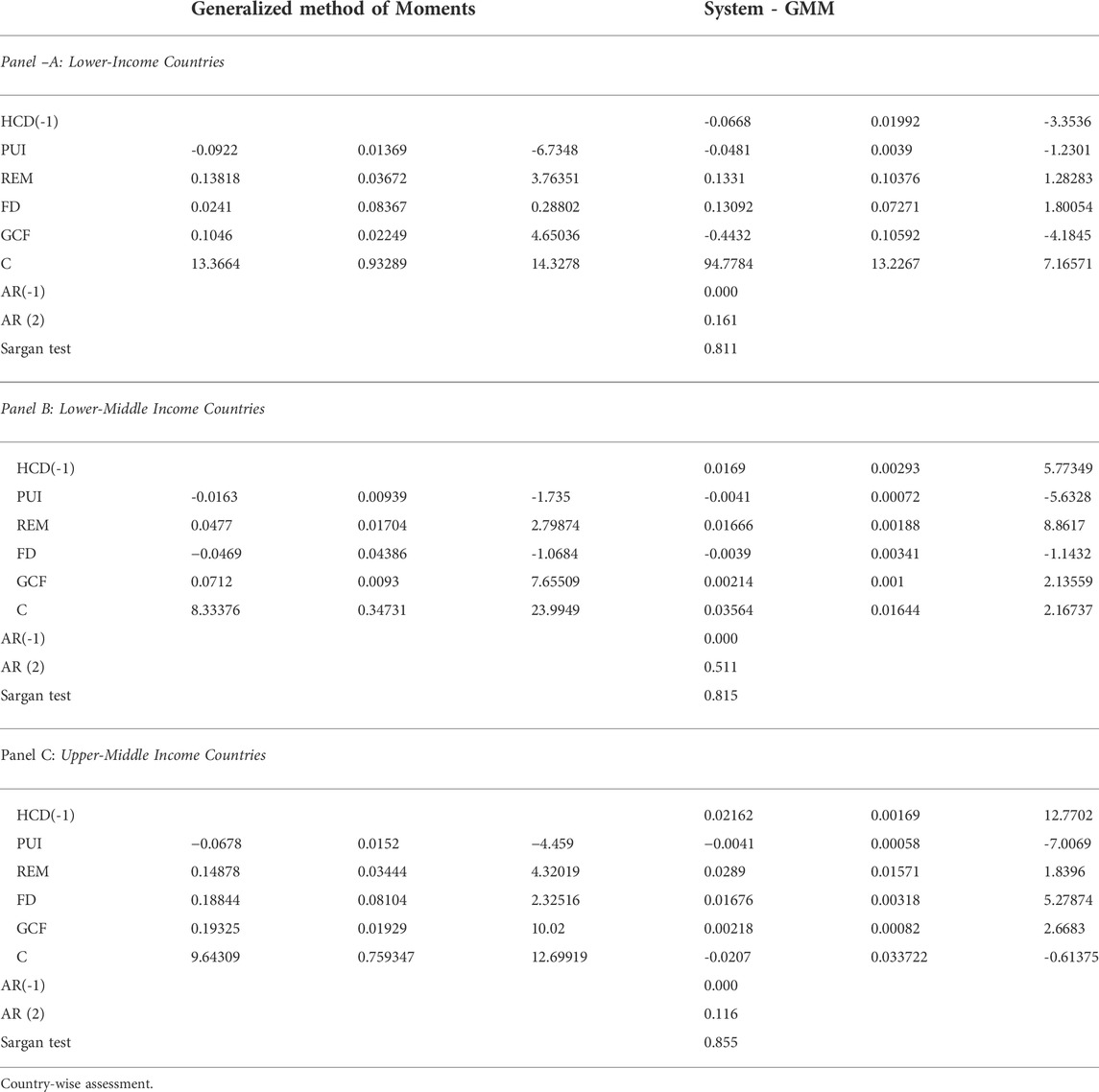

Next, the study moved to robustness assessment in empirical estimation by employing GMM and system GMM. The results of GMM and system-GMM are displayed in Table 7. For lower-income counties (see panel–A), the study reviled that policy uncertainty has an adverse impact on households consumption a coefficient of -0.0922 (-0.0481) in LIC, a coefficient of -0.0163 (-0.0041) in LMIC, and a coefficient of -0.0678 (-0.0041), respectively. Study findings suggest that the fear of uncertainties has adversely influenced the lower-income groups, thus reducing consumption.

While the impact of remittances revealed positive and statistically significant, suggesting that migrants’ money inflows in the economy have accelerated households consumption in LIC (a coefficient of 0.1381), LMIC (a coefficient of 0.0477), and UMIC (a coefficient of 0.1488), moreover the elasticity with system-GMM revealed the similar line of association in LIC (a coefficient of 0.1331), in LMIC (a coefficient of 0.0167), and UMIC (a coefficient of 0.0289), respectively. The notable fact has revealed that even though the role of remittances is positively connected with household consumption, the intensity is more prominent in lower-income countries in comparison with high-income countries.

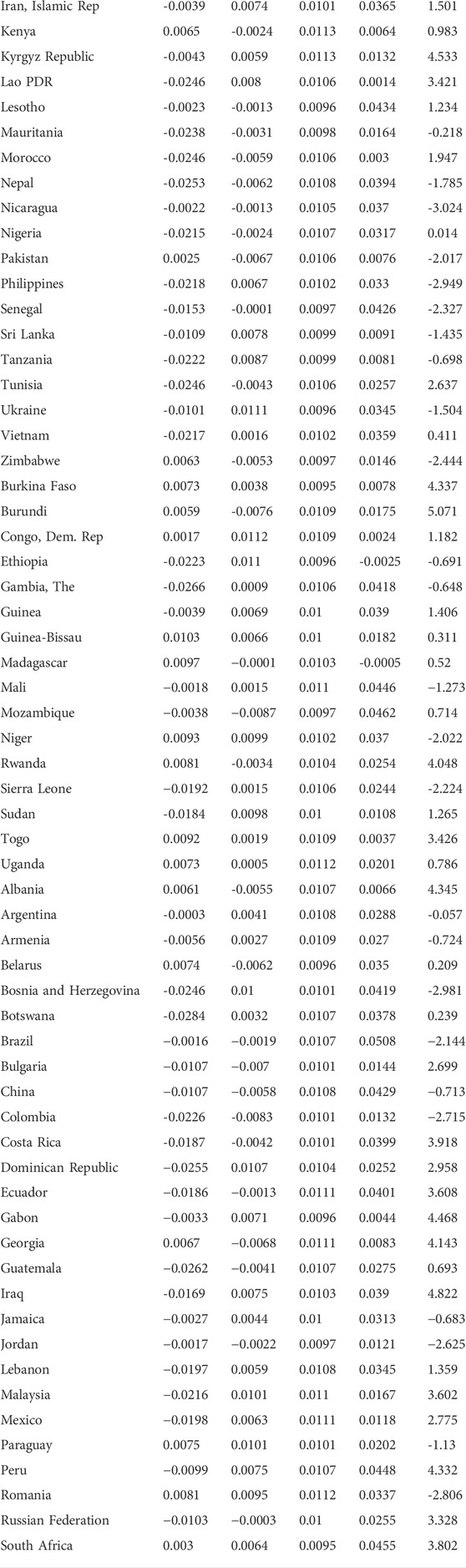

Next, the study implemented Ordinary Least Square to investigate the potential impact of pandemic uncertainties on household consumption considering country-level information. The results of the country-level estimation are displayed in Table 8. The study documented three association lines that refer to pandemic uncertainties on household consumption. First, the negative linkage, that is, uncertainties, discourages household normal consumption level and induces maintaining the financial security and stability in Botswana, Gambia, Dominican Republic, Bolivia, Nepal, India, Lao PDR, Morocco, Tunisia, Bosnia and Herzegovina, Mauritania, Honduras, Colombia, Benin, Ethiopia, Tanzania, Philippines, Vietnam, Malaysia, Nigeria, Mexico, Lebanon, Sierra Leone, Costa Rica, Ecuador, Sudan, El Salvador, Iraq, Cambodia, Senegal, Angola, Ghana, Congo, Rep, Sri Lanka, Bulgaria, China, Russian Federation, Ukraine, Belize, Peru, Armenia, Indonesia, Haiti, Kyrgyz Republic, Iran, Islamic Rep, Guinea, Mozambique, Gabon, Jamaica, Lesotho, Nicaragua, Mali, Jordan, Brazil, Algeria, Cameroon, Argentina. A study suggests that uncertainties discourage household consumption by considering financial security and liquidity. The second line of evidence revealed positive effects run from pandemic uncertainties on household consumption in Pakistan, South Africa, Cote d'Ivoire, Bangladesh, Burundi, Albania, Zimbabwe, Kenya, Georgia, Egypt, Arab Rep., Burkina Faso, Uganda, Belarus, Paraguay, Rwanda, Romania, Togo, and Niger. The third line of evidence is no effects of pandemic uncertainties on household consumption in Burundi, Albania, Zimbabwe, Kenya, Georgia, Egypt, Arab Rep., Burkina Faso, Uganda, Belarus, Paraguay, Rwanda, Romania, Togo, Niger, Madagascar, Guinea-Bissau.

Refers to remittances’ impact on households consumption, study findings revealed remittances disarrange households consumption in Congo, Rep, Mozambique, Benin, Colombia, Ghana, El Salvador, Burundi, Bulgaria, Georgia, Haiti, Pakistan, Nepal, Indonesia, Belarus, Morocco, China, Albania, Zimbabwe, Tunisia, Costa Rica, Guatemala, Bolivia, Belize, Rwanda, Mauritania, Cote d'Ivoire, Nigeria, Angola, Algeria, Kenya, Jordan, Bangladesh, Brazil, Ecuador, Lesotho, Nicaragua, Honduras, Russian Federation, Senegal, Madagascar. Study findings advocated that households tend to accumulate money flows for future investment capital accumulation after a certain standard of living. Our finding is in line with Ang, Jha (Ang et al., 2009). The second line of findings revealed positive nexus between remittances and households consumption in Egypt, Arab Rep., Uganda, Gambia, Sierra Leone, Mali, Vietnam, Togo, Armenia, Botswana, Cambodia, Burkina Faso, Argentina, Mexico, South Africa, Guinea-Bissau, Philippines, Guinea, Gabon, Iran, Islamic Rep. Iraq, Peru, Sri Lanka, Lao PDR, Tanzania, Cameroon, Romania, Sudan, Niger, India, Ethiopia, Ukraine, Congo, Dem. Rep. study postulated that excess money flows induce household spending, which is in line with Kakhkharov and Rohde (Kakhkharov and Rohde, 2020). Neutral effects are available in Bosnia and Herzegovina, Malaysia, Paraguay, Dominican Republic, Jamaica, Lebanon, Kyrgyz Republic. Study findings advocated that the recipients of migrants’ remittances do not affect household consumption, which is in line with Castaldo and Reilly (Castaldo and Reilly, 2015).

Discussion

Household consumption variability relies on macro-economic shocks such as piece hikes of necessity goods, political instability, and economic uncertainty. The impact of unforeseen and uncontrolled economic events adversely affected household consumption due to liquidity constraints, income instability and future insecurity. In line with the existing literature, study findings have extended the prevailing belief that uncertainties discourage households from spending additional consumption expenditures rather than a conservative approach. The magnitudes of PUI on household consumption revealed negative and statistically significant, suggesting household consumption tends to decline in the pandemic state, especially when the situation appears unpredicted. Adams Jr and Cuecuecha (Adams and Cuecuecha, 2013) found that households’ economic expectations deteriorated regarding these expectations and the uncertainty around these levels. According to theory, Uncertainty impacts the economic behavior of families; moreover, Uncertainty influences future consumption and should prompt conservative conduct, such as higher precautionary savings and liquidity, lower levels of consumption, and reduced consumption exposure to hazardous financial investments, among other things. Furthermore, household saving increases dramatically when the level of uncertainty regarding the future direction of income rises, A family may raise its savings by either consuming less or working more; however, most prior research on precautionary savings.

By understanding remittances as a source of income for the homes that receive them, it is possible to logically explain the link between remittance and household consumption in the United States. Traditional consumption models, such as the lifecycle and perpetual income theories of consumption, assert that the source of income has little impact on consumption behavior since families seek to smooth expenditure over a long period. Consequently, we should assume that families receiving remittances would act the same way any other home would under the same circumstances. Refers to remittances’ impact on household consumption, the study documented an U–invert association between remittances inflows and household consumption, implying that excess money inflows increase consumption propensity up to a certain level; after that, households tend to move savings for future consumption. Furthermore, the consumption level with migrant’s remittances has exhibited different magnfititutes with income group and economic status of the home economy. Migrant transfers are generally acknowledged as a substantial source of income for households and a significant source of foreign currency for the country (Zwager, 2005). According to a growing body of studies, remittances seem to have a favorable influence on development. Consequently, the government, international organizations, and non-governmental organizations (NGOs) collaborate to establish rules for improved remittance management to benefit families and the country.

Findings and conclusion

Household consumption patterns in society vary based on the macroeconomic state; macro volatility, inequality, poverty level, income constraints, and others have played a detrimental role. Furthermore, unforeseen economic uncertainties due to non-human events have a critical role in managing society’s consumption pattern. The motivation of the study is to investigate the impact of pandemic uncertainties on household consumption levels in Lower-income countries (LIC), Lower-Middle Income countries (LMIC) and Upper-Middle Income Countries (UMIC) for the period 1996-to 2020. The key findings of the study are as follows:

First, the cross-sectional dependency test revealed that research units share some common dynamics that variables exhibited cross-sectionally dependent. Moreover, the heterogeneous properties in research variables have been established by rejecting the null hypothesis of homogeneity. Second, panel data stationary tests have documented that all the variables have become stationary after the first difference I(1), and neither has been exposed to stationary after second difference I(2). Second, the study has implemented a panel cointegration test to document a long-run association between PUI REM, FD, G, and HC. Referring to Pedroni (Pedroni, 2004), Pedroni (Pedroni, 2001) cointegration test, the study found that most test statistics have established statistically significant confirmation of long-run cointegration. Furthermore, the panel contention test following Westerlund (Westerlund, 2007) established a similar line of conclusion that is a long-run association in empirical estimation.

Third, study findings with SUR revealed the negative nexus between pandemic uncertainties and household consumption, suggesting a state of uncertainties adversely influenced household consumption and motivated control consumption for liquidity. Our study findings are in line with existing literature see Chen, Qian (Chen et al., 2021), Wu (Wu, 2020), Baker, Farrokhnia (Baker et al., 2020b). The possible explanation regarding household consumption variability is the fare of unavoidable consequences due to economic uncertainties. Maintaining the normal course of life, households should maintain financial and food security with sufficient money flows. Therefore during pandemics, households become more cautious in their present consumption trend. In the study of Coibion, Gorodnichenko (Coibion et al., 2020), the authors postulated that pandemic uncertainties discourage households’ spending behavior and increase negative perception in recovering the economic adversity due to unforeseen causes.

On policy note, the study has come up with the following suggestion.

1. Household consumption stability has immensely relied on the availability of money in households and has promoted economic development by ensuring economic optimization. The study suggested that to ensure the continual flow of remittances in the economy, and the promotional offerings must be disclosed and implemented effectively.

2. Financial efficiency and intermediation have induced the migrant population to send foreign remittances to their relatives through formal financial channels, which accelerates economic activities and ensures household consumption stability, especially in the long run. Therefore, an efficient financial system has to be offered with operational and distributional efficiency.

3. Monetary and fiscal stability accelerated economic well-being and long-run growth with equitable development. Good governance and institutional quality in the economy are the prerequisites for establishing stability and reducing uncertainties, leading to long-term consumption stability. The study postulated that effective policy formulation and implementation would offer institutional effectiveness and stability in the economy.

The present study does not have certain limitations; first, it is suggested to consider the asymmetric framework for getting fresh evidence and explaining the nexus between uncertainties, remittances and household consumption for future studies. Second, further study might be initiated by including the most adversely affected economy with COVID-19 in one panel and the top 50 remittances receiving economy in another panel. The data homogeneity might reveal diverse results for further insight development. In addition, the outcomes of this research indicate that the EPU index should be incorporated in Households demand assessment models as an independent variable in addition to the conventional variables connected to economic considerations. Today’s complicated and unstable global economy makes this concern more important than ever. There may be a need for further empirical investigations using other methodology and data sets including various nations.

Data availability statement

Publicly available datasets were analyzed in this study. This data can be found here: WDI.

Author contributions

YY: data curating; empirical estimation; Final Preparation. MQ: introduction; data curation; empirical estimation, First Draft; Final Preparation. HX: literature survey; methodology; first draft; AM: literature survey; methodology; first draft; final preparation. FN: Literature survey, Discussion, Conclusion, Final Preparation. IB: literature survey; methodology.

Funding

This study received financial support from the Institutes for Advanced Research (IAR), United International University, Bangladesh: Ref: IAR/2022/PUB/022.

Conflict of interest

Author YY was employed by the company Agricultural Bank of China LTD Nanjing Chengbei Sub-branch.

The remaining authors declare that the research was conducted in the absence of any commercial or financial relationships that could be construed as a potential conflict of interest.

Publisher’s note

All claims expressed in this article are solely those of the authors and do not necessarily represent those of their affiliated organizations, or those of the publisher, the editors and the reviewers. Any product that may be evaluated in this article, or claim that may be made by its manufacturer, is not guaranteed or endorsed by the publisher.

References

Acma, M. Q. (2014). Comparative study on performance evaluation of mutual fund schemes in Bangladesh: An analysis of monthly returns. J. Bus. Stud. Q. 5 (4), 190.

Adams, R. H., and Cuecuecha, A. (2010). Remittances, household expenditure and investment in Guatemala. World Dev. 38 (11), 1626–1641. doi:10.1016/j.worlddev.2010.03.003

Adams, R. H., and Cuecuecha, A., The impact of remittances on investment and poverty in Ghana. World Development, 2013. 50: p. 24–40.

Adams, R. H. (2006). International remittances and the household: Analysis and review of global evidence. J. Afr. Econ. 15 (2), 396–425. doi:10.1093/jafeco/ejl028

Adams, R., Remittances, inequality and poverty: Evidence from rural Mexico. Migration and development within and across borders: Research and policy perspectives on internal and international migration, 2008: p. 101–130.

Alam, M. N., Alam, M. S., and Chavali, K. (2020). Stock market response during COVID-19 lockdown period in India: An event study. J. Asian Finance, Econ. Bus. 7 (7), 131–137. doi:10.13106/jafeb.2020.vol7.no7.131

Ali, M., Alam, N., and Rizvi, S. A. R. (2020). Coronavirus (COVID-19) — an epidemic or pandemic for financial markets. J. Behav. Exp. Finance 27, 100341. doi:10.1016/j.jbef.2020.100341

Altig, D., Baker, S., Barrero, J. M., Bloom, N., Bunn, P., Chen, S., et al. (2020). Economic uncertainty before and during the COVID-19 pandemic. J. Public Econ. 191, 104274. doi:10.1016/j.jpubeco.2020.104274

Andriamahery, A., and Qamruzzaman, M. (2022). A symmetry and asymmetry investigation of the nexus between environmental sustainability, renewable energy, energy innovation, and trade: Evidence from environmental kuznets curve hypothesis in selected MENA countries. Front. Energy Res. 9. doi:10.3389/fenrg.2021.778202

Andriamahery, A., and Qamruzzaman, M. (2022). Do access to finance, technical know-how, and financial literacy offer women empowerment through women’s entrepreneurial development? Front. Psychol. 12 (5889), 776844. doi:10.3389/fpsyg.2021.776844

Ang, A., Jha, S., and Sugiyarto, G., Remittances and household behavior in the Philippines. Asian Development Bank Economics Working Paper, 2009(188).

Athanasoulis, S. G., and Van Wincoop, E. (2000). Growth uncertainty and risksharing. J. Monetary Econ. 45 (3), 477–505. doi:10.1016/s0304-3932(00)00003-9

Azam, M. Q., Hashmi, N. I., Hawaldar, I. T., Alam, M. S., and Baig, M. A. (2022). The COVID-19 pandemic and overconfidence bias: The case of cyclical and defensive sectors. Risks 10 (3), 56. doi:10.3390/risks10030056

Baker, S. R., Bloom, N., Bloom, N., Davis, S. J., and Terry, S. J. (2020). Covid-induced economic uncertainty. National Bureau of Economic Research. doi:10.3386/w26983

Baker, S. R., Farrokhnia, R. A., Meyer, S., Pagel, M., and Yannelis, C. (2020). How does household spending respond to an epidemic? Consumption during the 2020 COVID-19 pandemic. Rev. Asset Pricing Stud. 10 (4), 834–862. doi:10.1093/rapstu/raaa009

Castaldo, A., and Reilly, B. (2015). Do migrant remittances affect the consumption patterns of Albanian households? South-Eastern Eur. J. Econ. 5 (1).

Chen, H., Qian, W., and Wen, Q. (2021). “The impact of the COVID-19 pandemic on consumption: Learning from high-frequency transaction data,” in AEA Papers and Proceedings.

Coddington, A. (1976). Keynesian economics: The search for first principles. J. Econ. literature 14 (4), 1258–1273.

Coibion, O., Gorodnichenko, Y., and Weber, M. (2020). The cost of the covid-19 crisis: Lockdowns, macroeconomic expectations, and consumer spending. Natl. Bureau Econ. Res.

Combes, J.-L., and Ebeke, C. (2011). Remittances and household consumption instability in developing countries. World Dev. 39 (7), 1076–1089. doi:10.1016/j.worlddev.2010.10.006

Debnath, M., and Nayak, D. K. (2022). Dynamic use of remittances and its benefit on rural migrant households: Insights from rural West Bengal. India: GeoJournal.

Faruqui, G. A., Ara, L. A., and Acma, Q. (2015). TTIP and TPP: Impact on Bangladesh and India economy. Pac. Bus. Rev. Int. 8 (2), 59–67.

Fetzer, T., Witte, M., Hensel, L., Jachimowicz, J. M., Haushofer, J., Ivchenko, A., et al. (2020). Global behaviors and perceptions in the COVID-19 pandemic.

Ganlin, P., Qamruzzaman, M., Mehta, A. M., Naqvi, F. N., and Karim, S. (2021). Innovative finance, technological adaptation and SMEs sustainability: The mediating role of government support during COVID-19 pandemic. Sustainability 13 (16), 9218–9227. doi:10.3390/su13169218

Guo, J., Liao, M., He, B., Liu, J., Hu, X., Yan, D., et al. (2021). Impact of the COVID-19 pandemic on household disinfectant consumption behaviors and related environmental concerns: A questionnaire-based survey in China. J. Environ. Chem. Eng. 9 (5), 106168. doi:10.1016/j.jece.2021.106168

Haroon, O., and Rizvi, S. A. R. (2020). COVID-19: Media coverage and financial markets behavior—a sectoral inquiry. J. Behav. Exp. Finance 27, 100343. doi:10.1016/j.jbef.2020.100343

Hongxing, Y., Abban, O. J., and Dankyi Boadi, A. (2021). Foreign aid and economic growth: Do energy consumption, trade openness and CO2 emissions matter? A DSUR heterogeneous evidence from africa’s trading blocs. PLOS ONE 16 (6), e0253457. doi:10.1371/journal.pone.0253457

Hossain, A., and Gani, M. O. (2022). Impact of migration on household consumption expenditures in Bangladesh using the coarsened exact matching (CEM) approach. Asian J. Econ. Bank. 6, 198–220. ahead-of-print(ahead-of-print). doi:10.1108/ajeb-10-2021-0117

Işık, C., Sirakaya-Turk, E., and Ongan, S. (2020). Testing the efficacy of the economic policy uncertainty index on tourism demand in USMCA: Theory and evidence. Tour. Econ. 26 (8), 1344–1357. doi:10.1177/1354816619888346

Jia, Z., Hajdari, B., Khalid, R., Wei, J., and Qamruzzaman, M. D., Economic policy uncertainty and financial innovation: Is there any affiliation? Preprints, 2020.

Jia, Z., Mehta, A. M., Qamruzzaman, M., and Ali, M. (2021). Economic Policy uncertainty and financial innovation: Is there any affiliation? Front. Psychol. 12, 631834. doi:10.3389/fpsyg.2021.631834

Jianguo, W., and Qamruzzaman, M. (2017). Financial innovation and economic growth: A casual analysis. INNOVATION Manag.

JinRu, L., and Qamruzzaman, M. (2022). Nexus between environmental innovation, energy efficiency, and environmental sustainability in G7: What is the role of institutional quality? Front. Environ. Sci. 10. doi:10.3389/fenvs.2022.860244

Kakhkharov, J., and Rohde, N. (2020). Remittances and financial development in transition economies. Empir. Econ. 59 (2), 731–763. doi:10.1007/s00181-019-01642-3

Karim, S., and Qamruzzaman, M. (2020). Corporate culture, management commitment, and HRM effect on operation performance: The mediating role of just-in-time. Cogent Bus. Manag. 7 (1), 1786316. doi:10.1080/23311975.2020.1786316

Karim, S., Qamruzzaman, M., and Jahan, I. (2022). Nexus between information technology, voluntary disclosure, and sustainable performance: What is the role of open innovation? J. Bus. Res. 145, 1–15.

Laborde, D., Martin, W., Swinnen, J., and Vos, R. (2020). COVID-19 risks to global food security. Science 369 (6503), 500–502. doi:10.1126/science.abc4765

Leduc, S., and Liu, Z. (2020). The uncertainty channel of the coronavirus. FRBSF Econ. Lett. 7, 1–05.

Li, J., and Qamruzzaman, M. (2022). Dose tourism induce Sustainable Human capital development in BRICS through the channel of capital formation and financial development: Evidence from Augmented ARDL with structural Break and Fourier TY causality. Front. Psychol., 1260.

Li, J., Song, Q., Peng, C., and Wu, Y. (2020). COVID-19 pandemic and household liquidity constraints: Evidence from micro data. Emerg. Mark. Finance Trade 56 (15), 3626–3634. doi:10.1080/1540496x.2020.1854721

Lingyan, M., Qamruzzaman, M., and Adow, A. H. E. (2021). Technological adaption and open innovation in SMEs: An strategic assessment for women-owned SMEs sustainability in Bangladesh. Sustainability 13 (5), 2942. doi:10.3390/su13052942

Liu, T., Pan, B., and Yin, Z. (2020). Pandemic, mobile payment, and household consumption: Micro-evidence from China. Emerg. Mark. Finance Trade 56 (10), 2378–2389. doi:10.1080/1540496x.2020.1788539

Mark, N. C., Ogaki, M., and Sul, D. (2005). Dynamic seemingly unrelated cointegrating regressions. Rev. Econ. Stud. 72 (3), 797–820. doi:10.1111/j.1467-937x.2005.00352.x

Mehta, A. M., Qamruzzaman, M., and Serfraz, A. (2022). The effects of finance and knowledge on entrepreneurship development: An empirical study from Bangladesh. J. Asian Finance, Econ. Bus. 9 (2), 409–418.

Mondal, R. K., and Khanam, R. (2018). The impacts of international migrants’ remittances on household consumption volatility in developing countries. Econ. Analysis Policy 59, 171–187. doi:10.1016/j.eap.2018.07.001

Nguyen, D. L., Grote, U., and Nguyen, T. T. (2017). Migration and rural household expenditures: A case study from Vietnam. Econ. Analysis Policy 56, 163–175. doi:10.1016/j.eap.2017.09.001

Pallage, S., and Robe, M. A. (2003). On the welfare cost of economic fluctuations in developing countries. Int. Econ. Rev. Phila. 44 (2), 677–698. doi:10.1111/1468-2354.t01-2-00085

Pedroni, P. (2004). Panel cointegration: Asymptotic and finite sample properties of pooled time series tests with an application to the PPP hypothesis. Econ. Theory 20 (3), 597–625. doi:10.1017/s0266466604203073

Pedroni, P. (2001). Purchasing power parity tests in cointegrated panels. Rev. Econ. Statistics 83 (4), 727–731. doi:10.1162/003465301753237803

Pesaran, M. H. (2007). A simple panel unit root test in the presence of cross‐section dependence. J. Appl. Econ. Chichester. Engl. 22 (2), 265–312. doi:10.1002/jae.951

Pesaran, M. H., Ullah, A., and Yamagata, T. (2008). A bias‐adjusted LM test of error cross‐section independence. Econom. J. 11 (1), 105–127. doi:10.1111/j.1368-423x.2007.00227.x

Pesaran, M. H., and Yamagata, T. (2008). Testing slope homogeneity in large panels. J. Econ. 142 (1), 50–93. doi:10.1016/j.jeconom.2007.05.010

Pu, G., Qamruzzaman, M., Mehta, A. M., Naqvi, F. N., and Karim, S. (2021). Innovative finance, technological adaptation and SMEs sustainability: The mediating role of government support during COVID-19 pandemic. Sustainability 13 (16), 9218. doi:10.3390/su13169218

Qamruzzaman, M. (2020). COVID-19 impact on SMEs in Bangladesh: An investigation of what they are experiencing and how they are managing? United International University. Available at SSRN https://ssrn.com/abstract=3654126. doi:10.2139/ssrn.3654126

Qamruzzaman, M., and Jianguo, W. (2020). Nexus between remittance and household consumption: Fresh evidence from symmetric or asymmetric investigation. J. Econ. Dev. 45 (3), 1–27.

Qamruzzaman, M., Karim, S., and Jahan, I. (2021). COVID-19, remittance inflows, and the stock market: Empirical evidence from Bangladesh. J. Asian Finance, Econ. Bus. 8 (5), 265–275.

Qamruzzaman, M., Karim, S., and Jianguo, W. (2019). Revisiting the nexus between financial development, foreign direct investment and economic growth of Bangladesh: Evidence from symmetric and asymmetric investigation. J. Sustain. Dev. Stud. 12 (2).

Qamruzzaman, M., Karim, S., and Wei, J. (2019). Does asymmetric relation exist between exchange rate and foreign direct investment in Bangladesh? Evidence from nonlinear ardl analysis. J. Asian Finance, Econ. Bus. 6 (4), 115–128. doi:10.13106/jafeb.2019.vol6.no4.115

Qamruzzaman, W. J. (2018). Does foreign direct investment, financial innovation, and trade openness coexist in the development process: Evidence from selected asian and african countries? Br. J. Econ. Finance Manag. Sci. 16 (1), 73–94.

Serfraz, A., Munir, Z., Mehta, A. M., and Qamruzzaman, M. D. (2022). Nepotism effects on job satisfaction and withdrawal behavior: An empirical analysis of social, ethical and economic factors from Pakistan. J. Asian Finance, Econ. Bus. 9 (3), 311–318.

Song, Q., Li, J., Wu, Y., and Yin, Z. (2020). Accessibility of financial services and household consumption in China: Evidence from micro data. North Am. J. Econ. Finance 53, 101213. doi:10.1016/j.najef.2020.101213

To, H., Grafton, R. Q., and Regan, S. (2017). Immigration and labour market outcomes in Australia: Findings from HILDA 2001–2014. Econ. Analysis Policy 55, 1–13. doi:10.1016/j.eap.2017.03.006

Uddin, M. A., and Alam, M. S. (2021). Personal remittances: An empirical study in Oman. J. Asian Finance, Econ. Bus. 8 (3), 917–929.

Westerlund, J. (2007). Testing for error correction in panel data. Oxf. Bull. Econ. Stat. 69 (6), 709–748. doi:10.1111/j.1468-0084.2007.00477.x

Wouterse, F. S., Migration, poverty, and inequality: Evidence from Burkina Faso. Vol. 786. 2008: Intl Food Policy Res Inst.

Wu, S. (2020). Effects of pandemics-related uncertainty on household consumption: Evidence from the cross-country data. Front. Public Health 8, 615344. doi:10.3389/fpubh.2020.615344

Wu, W., and Zhao, J. (2021). Economic policy uncertainty and household consumption: Evidence from Chinese household. J. Asian Econ., 101436.

Xu, S., Qamruzzaman, M., and Adow, A. H. (2021). Is financial innovation bestowed or a curse for economic sustainably: The mediating role of economic policy uncertainty. Sustainability 13 (4), 2391. doi:10.3390/su13042391

Yang, Y., Qamruzzaman, M., Rehman, M. Z., and Karim, S. (2021). Do tourism and institutional quality asymmetrically effects on FDI sustainability in BIMSTEC countries: An application of ARDL, CS-ardl, NARDL, and asymmetric causality test. Sustainability 13 (17), 9989. doi:10.3390/su13179989

Zhao, L., and Qamruzzaman, M. (2022). Do urbanization, remittances, and globalization matter for energy consumption in belt and road countries: Evidence from renewable and non-renewable energy consumption. Front. Environ. Sci. 10. doi:10.3389/fenvs.2022.930728

Keywords: households consumption, remittances, pandemic uncertainties, dynamic SUR, COVID-19

Citation: Yin Y, Qamruzzaman M, Xiao H, Mehta AM, Naqvi FN and Baig IA (2022) Nexus between uncertainty, remittances, and households consumption: Evidence from dynamic SUR application. Front. Environ. Sci. 10:950067. doi: 10.3389/fenvs.2022.950067

Received: 22 May 2022; Accepted: 09 August 2022;

Published: 05 September 2022.

Edited by:

Cem Işık, Anadolu University, TurkeyReviewed by:

Hayot Berk Saydaliev, Institute of Forecasting and Macroeconomic Research, UzbekistanMd Shabbir Alam, University of Bahrain, Bahrain

Copyright © 2022 Yin, Qamruzzaman, Xiao, Mehta, Naqvi and Baig. This is an open-access article distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution License (CC BY). The use, distribution or reproduction in other forums is permitted, provided the original author(s) and the copyright owner(s) are credited and that the original publication in this journal is cited, in accordance with accepted academic practice. No use, distribution or reproduction is permitted which does not comply with these terms.

*Correspondence: Md. Qamruzzaman, zaman_wut16@yahoo.com;

†ORCID: Ahmed Muneeb Mehta, orcid.org/0000-0001-6333-9077; Imran Ali Baig, orcid.org/0000-0002-2087-3621

Ying Yin1

Ying Yin1  Md. Qamruzzaman

Md. Qamruzzaman Ahmed Muneeb Mehta

Ahmed Muneeb Mehta