Green Experiential Marketing, Experiential Value, Relationship Quality, and Customer Loyalty in Environmental Leisure Farm

- 1Department of Accounting and Auditing, Guangxi University of Finance and Economics, Nanning, China

- 2School of Economics and Management, Foshan University, Foshan, China

Environmental/green marketing has emerged as one of the dominant paradigms of marketing in recent years. However, aspects, such as internationalization, the development of artificial intelligence, and stress from growing global competitive forces, have brought about changes in the way leisure farms approach experiential marketing with a significant environmental focus. In this context, the concept of relationship quality offers an opportunity for environmental leisure farms to understand how green experiential marketing impacts consumers’ perceived value and the ongoing interaction relationship. This study adopts a comprehensive perspective that includes green experiential marketing and relationship marketing that leisure farms use in order to enhance customer loyalty, and analyzes the effect of a series of elements inherent to customer psychic or personal needs. Seven hundred fifty-four valid copies of questionnaire were adopted in total. To verify the proposed model empirically, a survey of customers of environmental leisure farms in Taiwan was conducted. Structural equation modeling is conducted to examine the research hypotheses. The findings show that, overall, green experiential marketing has positive direct effects on experiential value and experiential value has positive direct effects on trust, commitment, and satisfaction. At the same time, trust and satisfaction have positive effects on attitudinal and behavioral loyalty. In addition, attitudinal loyalty has a positive influence on behavioral loyalty.

JEL Classifications: C83, M31, Q13, Z33.

Introduction

In the context of economic booms, people in urbanized environments are exposed to nonenvironmental, non-green, and unhealthy things and are trapped in an oppressive and tense situation. With increasing awareness of the need for environmental protection, consumers are paying more attention to the green experience and pursuing their physical health (Wu H. C. et al., 2018). This has urged leisure farms to enhance their environmental image, so as to give a positive impression to tourists and promote consumer loyalty to the farms. According to Owens (2000), the advent of new technologies, increasing numbers of competitors, and increasing wealth of consumers will change economic industries that focus on services, and lead a new consumption trend that focuses on experience (Chang and Horng, 2010; Maklan and Klaus, 2011; Lemon and Verhoef, 2016). In recent years, the experience economy has become a hot topic of discussion for economists and management scholars (Pine and Gilmore, 1998; Mathwick et al., 2001; Hosany and Witham, 2010; Brun et al., 2017), and the concept of experiential marketing has also emerged (Chang and Horng, 2010; Maklan and Klaus, 2011). According to Brun et al. (2017), current generic conceptualizations of experience may be too broad to be actionable and relevant in any one context. Indeed, measurement of variables could require differentiation based on the context (Hosany and Witham, 2010; Lemke et al., 2011; Maklan and Klaus, 2011), such as green experiential marketing. In this regard, green experiential marketing can be defined as that something environmentally friendly is added into a brand, product, or service, which brings consumers unforgettable experiential memories and enhances their sense of identity with the concept of environmental demands. Under the circumstances of sustainable development of environment and leisure farms, it is necessary to figure out how to make tourists perceive the significance of environmental protection and enhance their consuming intention. Thus, this study explores the role that green experiential marketing plays in the sustainable development of environment and leisure farms from the perspective of green marketing.

In the field of service marketing, better pre- and post-sales services are also required, after establishing the relationship, so as to maintain and enhance it (Maklan and Klaus, 2011; Monferrer-Tirado et al., 2016). Moliner et al. (2007) claimed that customers’ overall assessment of service providers is reflected in the perceived relationship quality (RQ), which is also a key mechanism for guiding customer behaviors (Arcand et al., 2017). The perceived RQ is defined as the degree of appropriateness in meeting the demands for customer relations (Hennig-Thurau and Klee, 1997; Olavarría-Jaraba et al., 2018). However, no previous studies have analyzed the possible RQ antecedents from the perspective of green marketing. Or, put another way, studies have failed to include the set of green experiential marketing and experiential value aspects needed by environmental leisure farms so that customer value and relations can be maintained (Olavarría-Jaraba et al., 2018). Based on the above arguments, this study aims to explore the mediating role of RQ in the relationship between green experiential marketing and consumers’ intentions to visit leisure farms.

Based on consumer decision-making theory, Kotler (1997) proposed that the consumer decision-making process comprises a “black box.” Because consumers’ decisions are deeply influenced by their cultural background, social culture, and personal psychological factors, they only make purchase decisions—which also comprise a subsequent behavior—following a complicated psychological process after being stimulated by external factors (Chang and Horng, 2010; Srivastava and Kaul, 2016). Consumer decision-making theory describes the antecedent variables as external stimuli to consumers, whereas the RQ is the psychological process of dealing with stimuli (Monferrer-Tirado et al., 2016); an attitude toward the stimuli is formed, and this is subsequently reflected as loyalty (Brakus et al., 2009; Srivastava and Kaul, 2016; Brun et al., 2017). However, in terms of RQ, there is still a question of whether loyalty behaviors are affected by attitude, which is derived from the antecedent variables (stimuli), or from the interaction effect of different attitudes originating from the psychological process (Maklan and Klaus, 2011; Olavarría-Jaraba et al., 2018). In fact, consumer motivation and decision-making for green product or service purchase differ from those for common product purchase. For consumers, green consumption is often not based on immediate self-interest, but on environmental altruism. Thereby, compared with the purchasing behavior pattern of common products, the purchase decision of green consumption is often more complicated. Despite green experiential marketing is an important source of stimulation, it still needs to judge the feelings brought by the stimulation via information processing and further transform it into positive emotions and attitudes. Experiential value may be an important intermediary variable between green experiential marketing and RQ thereinto. Mathwick et al. (2001) defined experiential value as consumers’ perception of and relative preference for product attributes or service performance. Thus, this study regards experiential value as an important antecedent variable that affects RQ.

According to our research purposes, this study attempts to provide several contributions. Firstly, this study approaches the consumer experience marketing in terms of green or environmental awareness. Secondly, we adopted the theory of consumer decision-making to verify the framework generated from green and relationship marketing. Thirdly, this study employs consumer decision-making theory to examine the relationships among green experiential marketing, experiential value, and RQ, and consumer loyalty is deepened in the view of management, through which it may develop during the process of stimuli, cognition, emotion, and action. Hence, recommendations for managers relevant to environmental sustainability will be put forward.

Literature Review and Hypotheses Development

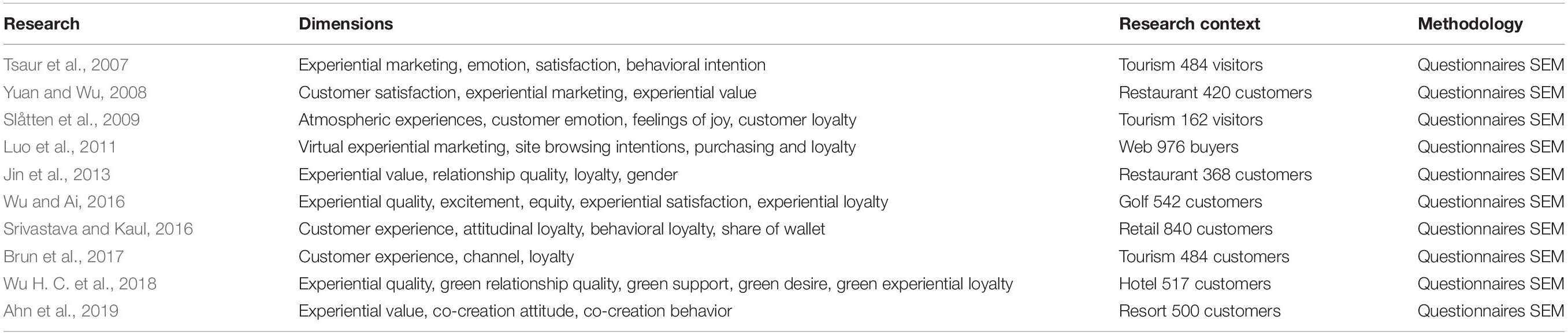

Theoretical Foundation

Referring to the study by Oliver (1997), this study proposes that the loyalty should be formed through the path of cognition–affect–conation–action. In the cognition phase, consumers will make evaluation based on stimulus or previous experience and knowledge (experiential value) (Brun et al., 2017). If satisfaction arises, it will enter the phase of affect. The affect phase focuses on the psychological level of consumers and is based on the cumulative experience of satisfaction (RQ). The conation phase means that consumers have repeated positive emotions and the commitment to repurchase. Finally, the action phase is the action control, indicating that the consumer’s purchasing pattern has been formed and any obstacle that prevents the repurchasing will be overcome (customer loyalty) (Srivastava and Kaul, 2016). Notwithstanding a lot of research support for the relationship among the variables of this study in a previous literature (as shown in Table 1), such as experiential value and loyalty, RQ and loyalty, experiential value and RQ, etc., but in allusion to the issues of environmental sustainable development and leisure farms, there are few research studies combining the concept of green marketing and experiential marketing for discussion and then developing the potential gaps in the literatures to be discussed in this study.

Customer loyalty has always been a hot topic in the field of marketing, and it has also driven a lot of research on loyalty marketing (Srivastava and Kaul, 2016; Brun et al., 2017). Oliver (1997) defined customer loyalty as “despite environmental changes and competitors’ efforts in marketing have a potential impact on the conversion of consumer behaviors after purchase, consumers are still willing to promise to buy or consume the same goods and services in the future, thereby resulting in repetitive purchases of the same brand or brands.” According to Oliver’s definition, customer loyalty can be divided into two parts: attitudinal loyalty and behavioral loyalty (Srivastava and Kaul, 2016). Attitudinal loyalty reflects the consumer’s psychological level, whereas behavioral loyalty mainly reflects the actual purchase behavior of consumers. Singh and Sirdeshmukh (2000) stated that customer loyalty is a behavioral tendency for consumers to continue to maintain relationships with service providers. Chao et al. (2007) argued that competitors in the retail industry will provide heterogeneous services and competitive prices to attract customers, but the customer loyalty may not follow (Monferrer-Tirado et al., 2016). The background of this research is similar to the retail industry. Managers of leisure farms offer differentiated and customized services to attract customers, expecting the generation of loyalty. However, Chao et al. (2007) measured customer loyalty only by the behavioral loyalty, holding that although the attitudinal loyalty is important to the expected cash flow in the future, it cannot be immediately reflected on the company’s financial performance. This study proposes that according to the view of relationship marketing, the operators of this industry should develop long-term stable relationships with customers for the purpose of establishing and maintaining customer relationships, although the behavioral loyalty can produce substantial benefits in the short term (Monferrer-Tirado et al., 2016). Therefore, subsequent studies are recommended to consider both attitudinal loyalty and behavioral loyalty when measuring brand loyalty (Zeithaml et al., 1996; Oliver, 1997; Palmatier et al., 2006). Particularly, the behavioral loyalty, also known as purchase loyalty, refers to the customer’s repeated purchase.

Green Experiential Marketing

Schmitt (1999) claimed that experience comprises an event in which an individual responds to certain stimuli, including the essence of the whole life, where the experience derives from engagement in or direct observation of the event, no matter whether the event is real, fantasy, or virtual (Pine and Gilmore, 1998; Lemke et al., 2011; Lemon and Verhoef, 2016). In this regard, the experience is translated into interaction between the body, the cognition, and the affect in the context of the environment, and any effort or skill of experience introduction will affect that interaction (Arnould et al., 2004; Chang and Horng, 2010; Maklan and Klaus, 2011; Brun et al., 2017). Affect and cognition are inseparable. Affect refers to the evaluation process in the mind, which derives the physical state and the additional mind, making experience the core of consumer behavior (Maklan and Klaus, 2011). Pine and Gilmore (1998) believed that experience crosses two dimensions, of which the core is customer participation and passive participation and active participation are contained. Hence, customers are critical to performance or event creation which yields experience. The greatest difference between experiential and traditional marketing is that traditional marketing puts emphasis on product features and benefits, whereas experiential marketing shifts the focus to the overall consumption situation and brand experience (Hosany and Witham, 2010; Lemke et al., 2011). However, environmental issues are now a core competitive factor in product markets (McDonagh and Prothero, 2014). Compared with the experiential and/or traditional marketing era, where the emphasis was on front-line polluters, environmentally friendly behaviors are being more widely adopted across all industries (Papadas et al., 2017). Some scholars have concluded that the green marketing has not performed to its full potential, and that existing research about environmental/green marketing is still in the stage of studying its applied value in practice (Fuentes, 2015; Papadas et al., 2017). Despite there is a lack of definitive results from previous research, this study is based on the current literature and aims to capture a more integrative perspective of green experiential marketing. To identify the purposes of environmental/green marketing, this study conceptualizes the green experiential marketing construct as a set of dimensions and defines it as a series of physical and psychological stimuli of environmental/green awareness while offering consumers products and services that have environmental value (Wu H. et al., 2018).

The green experiential marketing concept is based on the strategic experiential field. Schmitt (1999) proposed to cooperate with experiential providers to attract customers via five aspects of experience—sense, feel, think, act, and relation—which allow us to understand customer experience from a wide, integral and comprehensive angle. In this study, a multi-dimensional model is adopted for comprehension of perceived green experiential marketing. According to a large number of studies (Wu and Li, 2017), a multi-dimensional model is available for measuring green experiential marketing in an environmental leisure farm. These five aspects have been deemed as the basis for research in this field (e.g., Gentile et al., 2007; Brakus et al., 2009; Verhoef et al., 2009) and have become widely accepted (Lemon and Verhoef, 2016). The “sense” experience creates sensory impacts through perceptual stimuli, providing excitement, pleasure, and satisfaction, and creating a fresh and unique emotional or perceptual experience (Lemke et al., 2011). In the process of consumption at environmental leisure farms, consumers can experience psychological comfort and relaxation in the countryside. The “feel” experience aims to tap into consumers’ inner emotions and affects and enables consumers to generate positive emotional responses to related products and brands by providing that experience. The emotional experience generated via environmental leisure farms enables consumers to relieve stress, relax, increase their emotional communication with the environment, and experience enhanced emotional value. The “think” experience encourages consumers to think differently and creatively compared with in their day-to-day lives. Consumers gain think experiences in environmental leisure farms, learn about farm life, and observe people’s affairs in rural contexts. The “act” experience comprises the connection between body experience and lifestyle. By increasing the body experience, alternative lifestyles and ways of doing things are found, which enrich the lives of consumers (Lemke et al., 2011). The act experience in environmental leisure farms serves to transform the attitudes of consumers and create a common drive to protect the environment through participation in activities related to environmental protection, thereby promoting a positive experience. Finally, the “relate” experience links individuals to the broad cultural and social contexts reflected in a brand, allowing individuals to link with others, specific communities or cultures, and abstract entities (Srivastava and Kaul, 2016).

Based on the above arguments, the previous studies suggested that when it comes to the green marketing strategies of an environmental leisure farm, the green experiential marketing is critical to consumer experience determination (Wu H. C. et al., 2018). Meanwhile experiential value based on the customer experience is also of great significance (Marković and Raspor Janković, 2013). Wu and Li (2017) argued in their study that good experiential quality contributes to the positive perception of the experienced products for consumers, which is better than the expected perceptual experiential value. Similarly, Tsaur et al. (2007) stated that the five variables of experiential marketing can strongly influence consumers’ positive emotions and enhance their dedication and enjoyment in the process of experience. At environmental leisure farms, consumers can look for the relevance with green environmental protection, so as to deepen their recognition of farms. On the basis of the above reasoning, this study suggests that green experience marketing will enhance consumers’ experiential value. Thus, the following hypotheses are proposed:

H1a: Sense experience has a positive and significant impact on experiential value.

H1b: Feel experience has a positive and significant impact on experiential value.

H1c: Think experience has a positive and significant impact on experiential value.

H1d: Act experience has a positive and significant impact on experiential value.

H1e: Relation experience has a positive and significant impact on experiential value.

Experiential Value

Lam et al. (2004) argued that customer value refers to the overall value that customers obtain from products or services, including product value, service value, personnel value, and image value. Customer cost is the financial amount required to obtain value from products and services, including monetary cost, time cost, energy cost, and psychic cost. The true value of the customer comes from the gap between the total customer value and the customer cost. If the total customer value is greater than the customer cost, the value is positive; otherwise, it is negative (Huber et al., 2001; Flint et al., 2002, 2005). Mathwick et al. (2001) referred to customer value from the perspective of experience, calling it experiential value. They identified the relevant aspects of experiential value and defined it as a perception and relative preference for product attributes or service performance, stating that such value can be improved through interactions, but these interactions may help or hinder the achievement of consumer goals. Referring to customer value from the perspective of experience, as proposed by Holbrook (1999); Mathwick et al. (2001) classified experiential value into four types: customer return on investment, service excellence, aesthetics, and playfulness.

Zeithaml et al. (1996) advocated that improving experiential value leads to greater consumer satisfaction. Before buying, consumers already have a standard of service (i.e., an expectation), which is used to measure the service performance, resulting in a positive or negative evaluation (Oliver, 1997). If consumers experience cognitive value brought by their experiential activities, they will believe in the goods and services provided by the operators and respond in a kind and friendly manner (Duncan and Moriarty, 1997; Baker et al., 2002). Zeithaml (1988) argued that the greatest difficulty in value research lies in the multiple meanings value holds for consumers and the implicit symbolic meaning at the highest level. These aspects may involve an emotional payoff. The relationship between experiential value and RQ needs to be found for an overall comprehension of the various functions of experiential value in leisure farm settings. According to Wu and Li (2017), Wu H. C. et al. (2018) experiential value perceptions are closely related to interactions between direct experience and distant evaluations of feelings, and such interactions lay the basis for experiential value perception and determine the level of consumer RQ. Wu H. C. et al. (2018) found in the research results that the perceived experiential value, through the value-added concept of experiential marketing, can promote consumers’ satisfaction with the friendly green environment and enhance their trust in the green environment after the experience, thus leading to green experiential loyalty. Jin et al. (2013) examined the effects of experiential value on RQ in a full-service restaurant, finding experiential functions and value to be important antecedents to RQ in US restaurants. In our context, when consumers obtain emotional value from a better experience value at a leisure farm, they will have a high-level emotional reaction to the leisure farm, thus generating enhanced expectations and support for the operator, as well as a willingness to maintain the mutual relationship in return for the emotional payoff involved (Maklan and Klaus, 2011). Therefore, hypotheses are developed as follows:

H2a: Experiential value has a positive and significant impact on satisfaction with leisure farm.

H2b: Experiential value has a positive and significant impact on trust with leisure farm.

H2c: Experiential value has a positive and significant impact on commitment with leisure farm.

Relationship Quality

Crosby et al. (1990) stated that RQ is an overall assessment of the relationship intensity between buyer and seller. This assessment is in line with the needs and expectations of both parties, and these needs and expectations are based on past successful or failed experiences or events of both parties. Smith and Bolton (1998) also indicated that RQ is a high-level contract built on the results of various positive relationships (Olavarría-Jaraba et al., 2018), reflecting the overall relationship intensity and the degree of satisfaction of the parties in terms of needs and expectations, in the manner of a reciprocal output (Wulf et al., 2001). However, to date, there have been no explicit discussions on the mediators of RQ in green marketing, and few previous studies have discussed RQ from the perspective of environmental protection, in that experiential value can impact loyalty through mediators such as trust, commitment, and satisfaction (Monferrer-Tirado et al., 2016). The present study aims to address this deficiency. Therefore, referring to the concepts put forward by Wulf et al. (2001); Beloucif et al. (2004), Rauyruen and Miller (2007); Olavarría-Jaraba et al. (2018), this study uses satisfaction, trust, and commitment as the main aspects of RQ. This study not only verifies the causal relationship among the measurement variables, such as antecedent variable, dependent variable, and RQ, but also discusses the relationship among the measurement variables within the RQ (Ferro et al., 2016; Arcand et al., 2017).

Morgan and Hunt (1994) defined trust as the degree to which a relationship member has confidence in the reliability and honesty of a trading partner. Trust not only is about having confidence in a relationship partner but also centers on the individual’s willingness to take risky actions to support the partner (Garbarino and Johnson, 1999; Moliner et al., 2007; Olavarría-Jaraba et al., 2018). Trust can also be defined as the willingness to rely on a trusted and well-meaning partner. If customers receive high-quality services and are aware that service personnel are reliable and genuine, positive word of mouth will form (Prasad and Aryasri, 2008; Monferrer-Tirado et al., 2016). Caceres and Paparoidamis (2007) argued that long-term loyalty entails commitment, where if a customer has brand commitment, three important behavioral outputs will result: repeated purchase of the brand’s products, offsetting of changes caused by competition, and offsetting of negative feelings caused by dissatisfaction. It has been indicated in the studies from Wu and Ai (2016), Wu H. C. et al. (2018) that high trust and satisfaction arising from the process of experience are conducive to generating high customer loyalty. In long-term relationships with customers, if customers’ commitment can be continuously maintained, their relationship with the firm will be enhanced, which will increase purchase frequency (Prasad and Aryasri, 2008; Arcand et al., 2017). Furthermore, Caceres and Paparoidamis (2007) argued that the development of trust and commitment is strategically important, because it creates a relationship atmosphere between the two parties and directly affects the customer’s behavioral intentions (Monferrer-Tirado et al., 2016). Past research has illustrated that customer satisfaction is a key antecedent factor for customer loyalty and repeated purchases (Seiders et al., 2005). In the environmental setting, a leisure farm perceived to be environmentally friendly can make consumers more satisfactory with their product or service when they visit the farm (Wu H. C. et al., 2018). Prasad and Aryasri (2008) claimed that the quality of preferred service attributes will increase the satisfaction level and satisfaction strength (Hosany and Witham, 2010; Lemon and Verhoef, 2016). Additionally, Jin et al. (2013) investigated the mediating role of RQ on the connection between experiential value and relationship outcomes (attitudinal and behavioral loyalty) in full-service restaurants and found that the effective use of experiential value increased customers’ RQ to the restaurant, thereby increasing loyalty. Therefore, the following hypotheses are derived:

H3a: Trust has a positive and significant impact on consumers’ loyalty (behavioral and attitudinal) in leisure farms.

H3b: Satisfaction has a positive and significant impact on consumers’ loyalty (behavioral and attitudinal) in leisure farms.

H3c: Commitment has a positive and significant impact on consumers’ loyalty (behavioral and attitudinal) in leisure farms.

In the service industry, high contact between consumers and service providers is necessary. Customers with high satisfaction of service experience will have a high degree of trust in the service provided by the organization itself and the service provider (Arcand et al., 2017). Garbarino and Johnson (1999) demonstrated that satisfaction is an antecedent factor for trust, and that the higher the satisfaction, the higher the trust degree of consumers, no matter for product purchase or the business performance, between which there is a positive relationship (Moliner et al., 2007; Ferro et al., 2016). Lin et al. (2014) also believed that trust is a major element in the development of higher-order relationships, especially at the initial stage of relationship development, consumers’ imagination degree of demand and expectation for relationship strength and satisfaction should be enhanced so as to establish the cornerstone of stable relationships (Arcand et al., 2017). In other words, in environmental leisure farms, satisfied consumers will be more likely to increase short-term and long-term consumption levels (Hsieh and Hiang, 2004) than dissatisfied consumers by establishing trust with leisure farms (Ferro et al., 2016). Thus, this study explores that consumers show preference when they perceive services and environmental qualities provided by environmental leisure farms, then they will have higher trust in leisure farms. To sum up, the following hypothesis is proposed in this study:

H3d: Satisfaction has a positive and significant impact on trust in leisure farms.

Trust is the willingness to rely on trustworthy and good-faith exchange partners (Ferro et al., 2016). When consumers receive good quality services, they perceive the service providers as reliable and benevolent, thus generating positive reputation (Prasad and Aryasri, 2008). Arcand et al. (2017) mentioned that the key element of trust lies in the fact that consumers believe in the intentions and motivations of sellers that are beneficial to consumers and have the creation of positive consumer output in consideration. If consumers perceive that the business operator does not have any speculative behavior, but consider their own welfare, they will have higher trust in the operator (Ferro et al., 2016). Besides, Caceres and Paparoidamis (2007) considered that the development of trust and commitment is of strategic importance, as it forms the atmosphere of relationship between the two sides and directly influences consumers’ behavioral intention. In conclusion, the following hypothesis is proposed in this study:

H3e: Trust has a positive and significant impact on commitment in leisure farms.

Most previous studies have considered attitude as the antecedent factor of behavior (Zaltman and Wallendorf, 1983; Srivastava and Kaul, 2016). Indeed, Oliver (1997) proposed a loyalty model that divides customers’ loyalty regarding products or services into four stages (Srivastava and Kaul, 2016): cognitive loyalty, emotional loyalty, attitudinal loyalty, and behavioral loyalty. These four stages have a sequential relationship. In addition, when the customer generates an intention to recommend and repurchase, the behavioral loyalty stage will start, resulting in substantial purchase behavior. McMullan and Gilmore (2003) echoed Oliver’s (1997) view that loyalty can be divided into four stages, and that these stages come one after another. They also indicated that behavioral loyalty always comes after attitudinal loyalty (Srivastava and Kaul, 2016). Based on the results of past research on customer loyalty, the following final hypothesis is proposed.

H4: Consumers’ attitudinal loyalty has a positive and significant impact on behavioral loyalty.

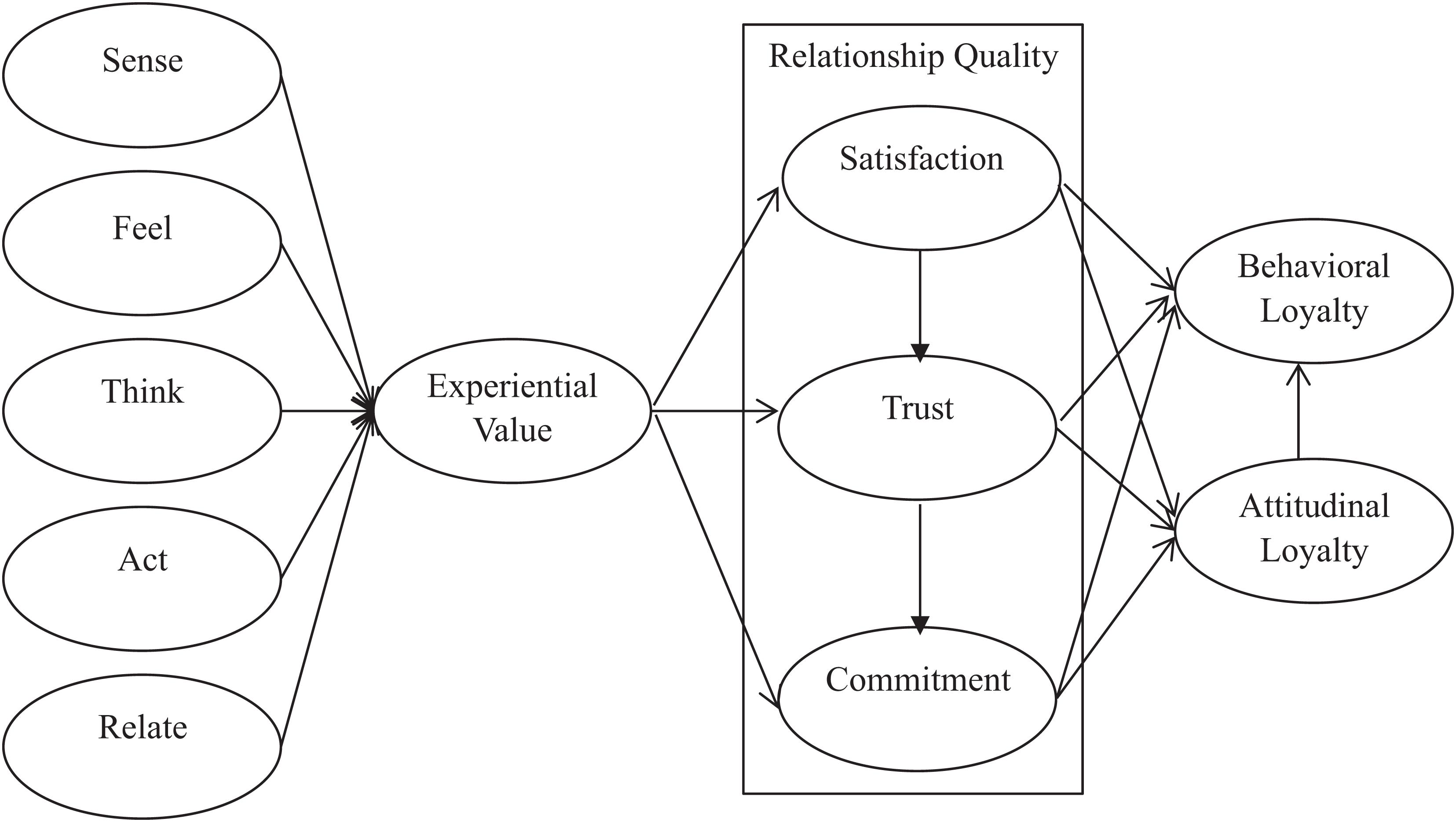

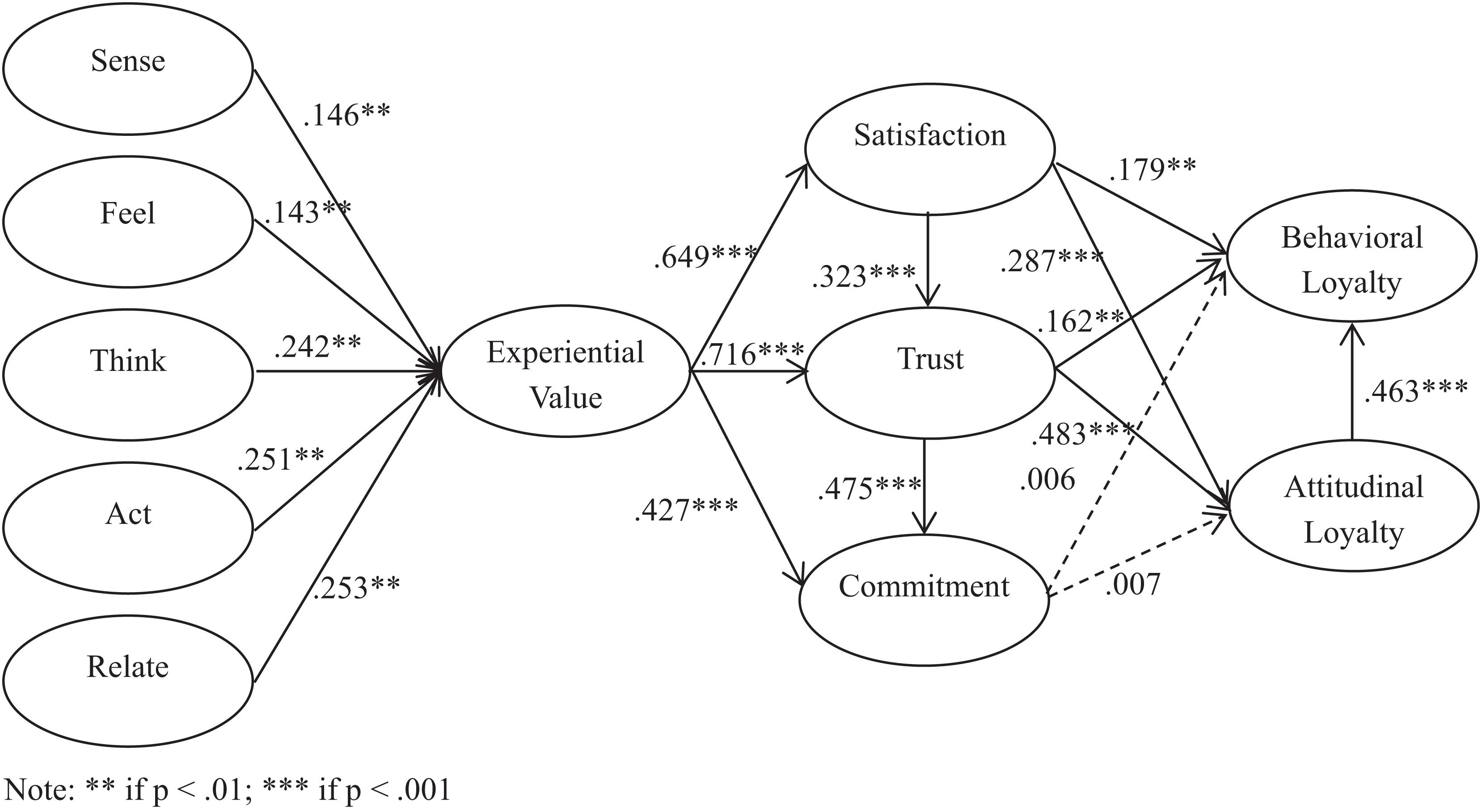

Based on the above arguments, this study proposes the following research framework in Figure 1.

Methodology

Sampling

The questionnaire used in this study was designed based on extant literature about experiential marketing (e. g., Kumar et al., 1995; Garbarino and Johnson, 1999; Schmitt, 1999; Moliner et al., 2007). Two pre-tests and several revisions were undertaken. The final questionnaire comprised three sections focusing on the following areas: (1) the consumer’s perceived experiential marketing and experiential value provided by an environmental leisure farm whose services they had used, (2) the consumer’s overall satisfaction with, trust in, and commitment and loyalty to the environmental leisure farm, and (3) demographic information on the consumer. Sampling of all leisure farms is difficult on account of numerous leisure farms in Taiwan; thus, purposive sampling was adopted. Moreover, some principles for sampling were set so as to accurately measure consumers’ perceptions of the variables in the study and improve external validity. First, it intends for investigation of consumers’ actual cognition to environmental leisure farms. Respondents are those who have been to environmental leisure farms, for those who have just been to general leisure farms may not have explicit expression of their feelings toward the importance of environmental protection; thereby, the effect of each variable on customer loyalty is impossible to measure. Second, since consumers with a clear environmental awareness are constituted by the sample, the question was contained to eliminate those who were less inclined to seek environmental leisure farms in the near future with the purpose of representativeness enhancement of samples, which expressed “Do you have environmental awareness?” One thousand copies of questionnaire were distributed among environmental leisure farm consumers, and 761 were returned, giving a 76.1% return rate. After removing the copies that were considered invalid, 754 remained for use in our empirical analysis.

Of these 754 samples, 53% of the participants were male, and 47% of the participants were female; 51.7% were aged less than 30 years; 82.1% had completed university courses; and the group was distributed into equal thirds regarding personal average monthly income (less than 600 USD, 600–1,300 USD, and more than 1,300 USD). In addition, 486 respondents reported having a relationship with a leisure farm for fewer than 2 years, 115 reported a relationship of 2–3 years, and 153 reported a relationship of longer than 3 years. To confirm whether there are differences among the samples in different background variables, this study conducted independent sample t test in terms of gender, income, age, and other factors. The results show that there is no significant influence when the sample is placed in different background variables. Thus, sample segments are not a critical issue.

Measurements

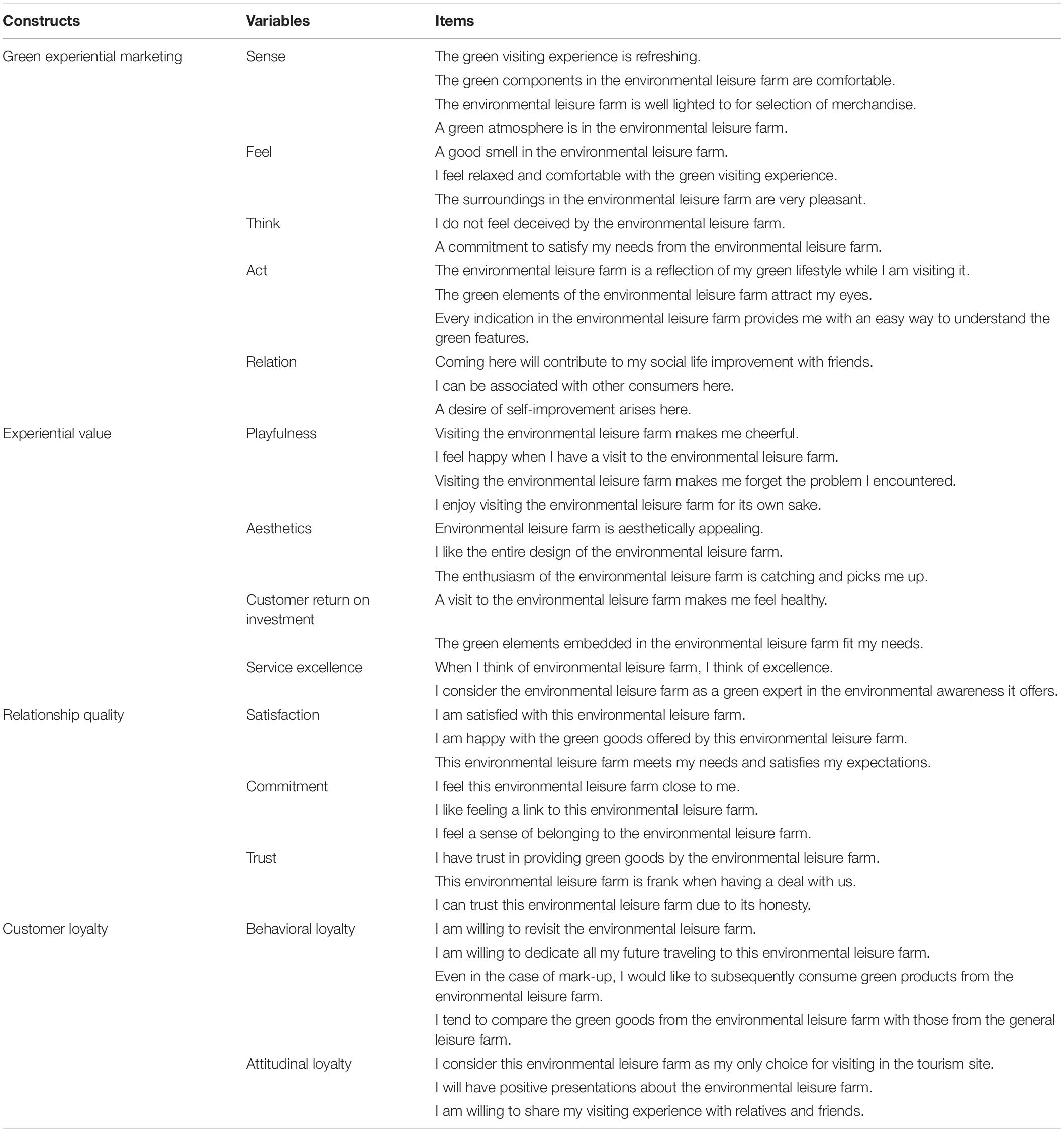

Green Experiential Marketing

We developed the experiential marketing scale based on Schmitt’s (1999) model. To enrich the items with the concept of green marketing, the study has modified the content of the items and conducted a pre-test before the formal test to check the availability of the items. In the pre-test, 53 samples were tested, and the factor analysis results show that the measurement variables can be extracted effectively and achieved good reliability (Cronbach’s α values of all variables are higher than 0.7). Thus, this scale was adopted for a formal test. The objective was to measure the five main dimensions and the subdimensions thereof, using a short, user-friendly scale that would ensure a high response rate. Items were included to measure perceptions of sense (4 items), feel (3 items), think (2 items), act (4 items), and relation (3 items).

Experiential Value

We used items adapted from the dimensions of Mathwick et al.’s (2001) scale of experiential value. Items were included to measure perceptions of playfulness (4 items), aesthetics (3 items), customer return on investment (2 items), and service excellence (2 items).

Relationship Quality

Relationship quality refers to the overall nature of the relationship between the consumer and the firm and views fulfilling consumers’ needs as central to relationship success. Beloucif et al. (2004); Rauyruen and Miller (2007) proposed that RQ is a three-dimensional construct consisting of satisfaction, commitment, and trust. Specifically, satisfaction was measured using a five-point semantic differential scale, as recommended by Ganesan (1994). Commitment was measured using three items adapted from scales by Garbarino and Johnson (1999); Morgan and Hunt (1994). Trust was measured using a five-point semantic differential scale, as recommended by Morgan and Hunt (1994); Kumar et al. (1995), Garbarino and Johnson (1999).

Customer Loyalty

Previously, the literature has divided customer loyalty into two categories: behavioral loyalty, which means repurchase behavior, and attitudinal loyalty, meaning recognition and attitude (Oliver, 1997; Chaudhuri and Holbrook, 2002). This study applied a five-point Likert scale to measure customer loyalty with respect to the following items: behavioral loyalty (4 items) and attitudinal loyalty (3 items). All items are using five-point Likert scales (1 = totally disagree; 5 = totally agree) and shown in Table 2.

Data Analysis Strategy

This study tested the hypotheses of research framework and included paths via structural equation modeling (SEM). For construct with a higher-order factor structure (green experiential marketing, experiential value RQ, and customer loyalty), if the traditional regression model is used, the effect between parameters is difficult to be tested. Thus, SEM is adopted in this study for model test and hypothesis verification. Structural validity analysis was performed using the IBM-AMOS statistical program, v. 23.0 (New York, NY, USA) for Windows; this program was also used to construct the structural prediction model, specifically, verification of the structural linear prediction hypothesis (path analysis) (de la Fuente et al., 2020).

Model Estimate

The latent variable SEM is conveniently divided into two parts: the latent variable model and the measurement model. The latent variable model (sometimes called the structural model) is (Eq. 1).

where ηi is a vector of latent endogenous variables for unit i, αη is a vector of intercept terms for the equations, B is the matrix of coefficients giving the expected effects of the latent endogenous variables (η) on each other, ξi is the vector of latent exogenous variables, Γ is the coefficient matrix giving the expected effects of the latent exogenous variables (ξ) on the latent endogenous variables (η), and ζi is the vector of disturbances. The i subscript indexes the ith case in the sample (Bollen and Noble, 2011). In this study, sense (ξ1), feel (ξ2), think (ξ3), act (ξ4), and relation (ξ5) are latent exogenous variables; experiential value (η1), satisfaction (η2), commitment (η3), trust (η4), attitudinal loyalty (η5), and behavioral loyalty (η6) are latent endogenous variables. According to 17 paths in our research framework, this study forms six equations. To illustrate this model in equation form, consider the equation for the latent green experiential marketing variables [sense (ξ1), feel (ξ2), think (ξ3), act (ξ4), and relation (ξ5)] for experiential value (η1) (Eq. 2),

and the equation for satisfaction variable (η2) (Eq. 3),

and the equation for commitment variable (η3) (Eq. 4),

and the equation for trust variable (η4) (Eq. 5),

and the equation for attitudinal loyalty variable (η5) (Eq. 6),

and the equation for behavioral loyalty variable (η6) (Eq. 7),

Data Analysis

Assessing Measurement Model

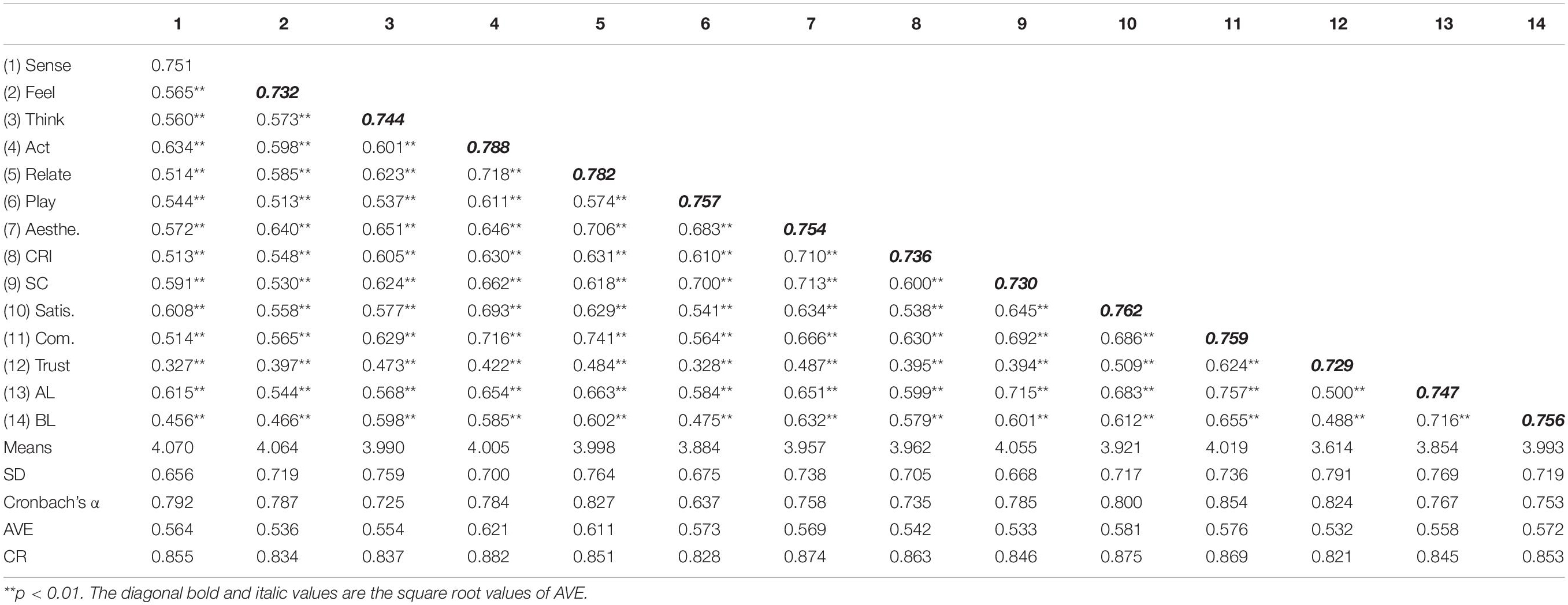

As Table 3 shows, all scales are reliable, with Cronbach’s α ranging from 0.725 to 0.854. In order to gauge validity, this study adopted the confirmatory factor analysis (CFA) using AMOS 23.0 to verify the validity of the construct, which includes convergent and discriminant validity. Hair et al. (2010) recommended convergent validity criteria as follows:(1) standardized factor loading of items higher than 0.5, (2) average variance extracted (AVE) above 0.5, and (3) composite reliability (CR) above 0.7. As Table 3 indicates, all three criteria for convergent validity are met.

The criterion for discriminant validity is the square root of the AVE for one dimension greater than the correlation coefficient with any other dimension(s). As Table 3 shows, correlation coefficients are all less than the square root of the AVE within one dimension, suggesting that each dimension in this study has good discriminant validity.

An Examination of the Structural Model

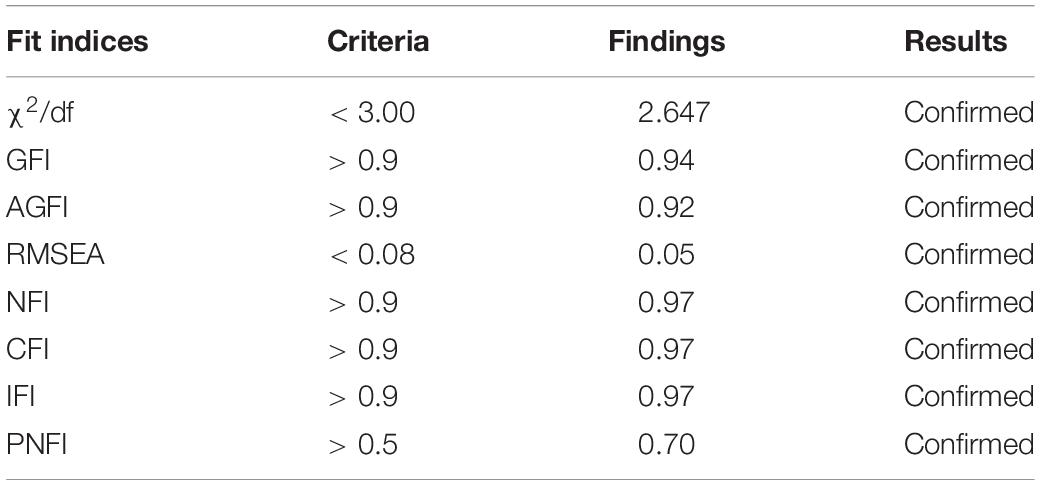

In this study, the measurement patterns of the above-mentioned variables are established according to the research framework, and the model matching degree of the SEM is adopted. For mode matching tests, Bagozzi and Yi (1988) considered that the size of the sample should be considered, and suggested that when the mode fit is measured by the ratio of χ2 to the degree of freedom (df), it generally does not exceed 3 (Hair et al., 2010). In the study, green experiential marketing, experiential value, RQ, and customer loyalty are often higher-order constructs in nature, with items measuring them as indirect reflective measures of both second- and first-order factors associated with them, where the green experiential marketing, experiential value, RQ, and customer loyalty are umbrella terms for multiple sub-constructs. Cadogan and Lee (2013) suggested that research should avoid developing and evaluating a model containing a direct link from the antecedent variable to the aggregate endogenous variable. However, this study aims to explore the role of green experiential marketing in the consumer decision-making process. Furthermore, according to research purposes and hypotheses, the experiential value is measured from the first-order construct in order to optimize the overall fitness index of the model and lower the complexity of the model. In this study, 754 valid copies of questionnaire were analyzed. The results are shown in Table 4. The ratio of χ2 to its DOF is less than 3; PNFI is greater than 0.5; goodness of fit index (GFI), adjusted goodness of fit index (AGFI), normed fit index (NFI), comparative fit index (CFI), and incremental fit index (IFI) are all greater than 0.9; root mean square error of approximation (RMSEA) is less than 0.08 (Jöreskog and Sörbom, 1993). The moderation of this research model is acceptable.

Verification of Structural Model

Correlations among variables were detected using SEM. There are many items in the consideration of certain facet scales. The results are shown in Figure 2. The path coefficients of sense (β = 0.146, p < 0.01), feel (β = 0.143, p < 0.01), think (β = 0.242, p < 0.01), act (β = 0.251, p < 0.01), and relation (β = 0.253, p < 0.01) to self-efficacy are statistically positive and significant; thus, H1a–e is supported. Similarly, the path coefficients of experiential value for trust (β = 0.716, p < 0.001), commitment (β = 0.427, p < 0.001), and satisfaction (β = 0.649, p < 0.001) are statistically positive and significant, meaning that H2a–c are also supported. In addition, the path coefficients of trust (β = 0.162, p < 0.01; β = 0.483, p < 0.001) and satisfaction (β = 0.179, p < 0.01; β = 0.287, p < 0.001) for behavioral and attitudinal loyalty are statistically positive and significant. Thus, the higher a customer’s degree of trust and satisfaction in an environmental leisure farm, the higher their behavioral and attitudinal loyalty. Thus, there is support for H3a and H3b. However, the path coefficients of commitment for behavioral and attitudinal loyalty are 0.006 and 0.007 (p > 0.1); then, H3c was not supported. The path coefficients of satisfaction→ trust (β = 0.323, p < 0.001) and trust→ commitment (β = 0.475, p < 0.001) were statistically positive and significant; thus, H3d and H3e were supported. The coefficient of attitudinal loyalty on behavioral loyalty is 0.463 (p < 0.001), so H4 is also supported. The R2 and Stone–Geisser Q2 values obtained through the blindfolding procedures for experiential value (Q2 = 0.368; R2 = 0.385), trust (Q2 = 0.322; R2 = 0.573), commitment (Q2 = 0.217; R2 = 0.382), satisfaction (Q2 = 0.482; R2 = 0.534), attitudinal loyalty (Q2 = 0.362; R2 = 0.443), and behavioral loyalty (Q2 = 0.324; R2 = 0.485) were larger than 0, supporting that the model has predictive relevance (Hair et al., 2017).

Discussion

Previous studies have emphasized the significance of sustainability in intensely competitive markets. This study contributes to the literature from three perspectives: (1) we demonstrate, for the first time, an integral and comprehensive approach toward green experiential marketing for environmental leisure farms; (2) by incorporating prior studies’ findings on the role of green experiential marketing, experiential value, RQ, and customer loyalty, we examine the correlations among these constructs; and (3) by verifying the nomological network of the green experiential marketing scale, we provide support for the findings of previous studies in terms of the positive effect of green experiential marketing on experiential value. Based on the above research findings, it makes substantial contributions to theories and practice. In theoretical aspect, green experiential marketing proposed in this study is combined with the concepts of green marketing and experiential marketing; thus, specific measurement items are proposed, and good reliability and validity are achieved. Furthermore, the research framework is constructed through the formed sequence of consumer loyalty proposed by Oliver (1997), and the results obtained after verification enrich the degree of generalization of consumer decision theory in various fields. In regard to the practical part, the findings of this study provide administrators and marketers with emphasis on environmental awareness and green experience, which not only enhance consumer intention toward leisure farms but also demonstrate their social responsibility for environmental conservation, and further enhance business reputation and positive feelings of consumers. Specific theories and management implications are described as follows.

Theoretical Implications

To the best of our knowledge, this is the first study to (1) conceptualize and operationalize the broad meaning of green experiential marketing and (2) build an integrated and empirically tested framework of this concept. Our findings are significant to the further development of environmental/green marketing. Generally speaking, the results offer four main theoretical implications. First, the development of an economical green experiential marketing scale can be used in future studies of green marketing. From the methodological point of view, this study incorporates the green marketing concept into Schmitt’s (1999) experiential marketing scale, which results in a holistic scale of green experiential marketing (Maklan and Klaus, 2011). The verification results of our measurement model confirm the reliability and validity of five dimensions of green experiential marketing and support its use in scholarly research in the future. Similar to Hosany and Witham (2010), our findings establish the importance of five dimensions in explaining the outcome variable of experiential value.

Second, this study provides an updated and comprehensive investigation into relationship marketing strategies, which extends the scope of earlier studies of green marketing (e.g., Menon and Menon, 1997) and relationship marketing (e.g., Morgan and Hunt, 1994; Garbarino and Johnson, 1999; Rauyruen and Miller, 2007; Olavarría-Jaraba et al., 2018). Most empirical studies on relationship marketing to date have emphasized the functional/emotional activities related to relationship marketing strategies (e. g., Maklan and Klaus, 2011; Lemon and Verhoef, 2016; Olavarría-Jaraba et al., 2018). Our results suggest that environmental leisure farms employ green initiatives at an individual consumer level. The confirmation of H1a–e agrees with Lemke et al.’s (2011), Lemon and Verhoef’s (2016), Brun et al.’s (2017), findings and seems to underline the need to focus on experiential value in the green context, and in particular as a key factor for environmental leisure farms to build relationships with consumers.

Third, in line with Brun et al.’s (2017) advocation for additional research, this study explores the combination of green experiential marketing and relationship marketing and investigates the relationships among experiential value, RQ (satisfaction, commitment, and trust), and customer loyalty (behavioral and attitudinal loyalty). The findings with regard to these relationships are in line with those of Oliver (1997); Monferrer-Tirado et al. (2016), Srivastava and Kaul (2016). They suggest a four-stage framework that demonstrates a hierarchical approach to loyalty formation. Specifically, the results indicate that experiential value has direct effects on satisfaction, commitment, and trust (H2a–c); satisfaction and trust have direct effects on behavioral and attitudinal loyalty (H3a, H3c); and attitudinal loyalty has a direct effect on behavioral loyalty (H4). Similarly, Srivastava and Kaul (2016) reported that attitudinal loyalty leads to behavioral loyalty. In the green context, according to the barometer of Monferrer-Tirado et al. (2016) about RQ, the approach to RQ defined in recent works has been confirmed (Beloucif et al., 2004; Rauyruen and Miller, 2007; Olavarría-Jaraba et al., 2018) regarding three variables: trust, commitment, and satisfaction. Specifically, satisfaction and trust act as antecedents of behavioral and attitudinal loyalty.

Managerial Implications

This study analyzes the effect of experiential elements (green experiential marketing and experiential value) on RQ, where RQ is found to affect consumer loyalty. By integrating green experiential marketing into the relationship marketing framework, this study takes the lead in adopting managerial issues. The findings help to explain the effect of RQ between customers and environmental leisure farms.

This study also provides insights for operators. First, our findings on the aspects of sense, feel, think, act, and relation in the green experiential marketing scale can help managers of environmental leisure farms to devise appropriate green marketing actions. For example, creating elaborate physical surroundings to induce customers’ positive emotional perceptions of the green experience might be critical, whereas employing a green-specific experience design may facilitate customers to sense the importance of environmental protection and create significant differentiation from ordinary leisure farms.

Second, our findings offer interesting implications with regard to maintaining each RQ dimension. In an atmospheric context, the feel and sense stimuli at environmental leisure farms contribute to positively perceived value and enhance customer satisfaction, commitment, and trust. This also suggests that green experiential activities (e.g., organic vegetables, use of recycled materials) offer a differentiation strategy to managers for (1) improving the green brand image of environmental leisure farms in the long term and (2) adjusting their green experiential marketing strategy through increasing the drive for environmental protection. Moreover, RQ evolves over time, so environmental leisure farms need to pay constant attention to the evolution of customer demands and expectations so as to continually update their experiential value. As some customers psychologically tend to cultivate relationships than others to a certain extent, it may be critical to determine the level of experiential value for customers using services and natural facilities of the leisure farm, and for those who turn to competitors.

Third, the study provides new insights into loyalty by demonstrating the roles of customer RQ and green experiential marketing in a four-stage framework. Furthermore, the findings can help operators to understand how outcomes from loyalty can be achieved and used. This study suggests that environmental leisure farms should enhance attitudinal loyalty first and then create specific consumption behavior. If customers perceive that the leisure farm has spent time addressing their needs and offering the best leisure environment, this constitutes a fundamental step in promoting emotional or psychological attachment and, therefore, engagement in desired (repurchase) behavior.

Limitations and Future Research

The above conclusions should be considered in light of the study’s limitations, which also suggest future directions of research. First, the sampling region of the study was confined to Taiwan, which limits the generalization of the results. Taiwan is a popular tourist attraction in Asia, and the conditions of its environmental leisure farms are on a par with those of other Asian countries, such as China, Thailand, Japan, Malaysia, and Vietnam. Although environmental leisure farms have developed in Taiwan, they are still rare in other countries. Given this, new research could compare the proposed relationships in other countries to improve the generalization of results.

Furthermore, it would be interesting to study the possible influence of other factors related to customer demographics, such as age, gender, and education level, as well as potential moderating effects related to loyalty, involvement, service quality, or personal interactions.

Data Availability Statement

The raw data supporting the conclusions of this article will be made available by the authors, without undue reservation.

Ethics Statement

The studies involving human participants were reviewed and approved by the University of Taipei. The patients/participants provided their written informed consent to participate in this study.

Author Contributions

This study is a joint work of the four authors. T-CL and MP contributed to the ideas of educational research, collection of data, empirical analysis, data analysis, design of research methods, and tables. MP participated in developing a research design, writing, and interpreting the analysis. All authors contributed to the literature review and conclusions.

Conflict of Interest

The author declares that the research was conducted in the absence of any commercial or financial relationships that could be construed as a potential conflict of interest.

References

Ahn, J., Lee, C. K., Back, K. J., and Schmitt, A. (2019). Brand experiential value for creating integrated resort customers’ co-creation behavior. Int. J. Hosp. Manag. 81, 104–112. doi: 10.1016/j.ijhm.2019.03.009

Arcand, M., PromTep, S., Brun, I., and Rajaobelina, L. (2017). Mobile banking service quality and customer relationships. Int. J. Bank Mark. 35, 1068–1089. doi: 10.1108/ijbm-10-2015-0150

Bagozzi, R. P., and Yi, Y. (1988). On the evaluation of structural equation models. J. Acad. Mark. Sci. 16, 74–94.

Baker, J., Parasuraman, A., Grewal, D., and Voss, G. B. (2002). The influence of multiple store environment cues on perceived merchandise value and patronage intentions. J. Mark. 66, 120–141. doi: 10.1509/jmkg.66.2.120.18470

Beloucif, A., Donaldson, B., and Kazanci, U. (2004). Insurance broker–client relationships: an assessment of quality and duration. J. Financial Serv. Mark. 8, 327–342. doi: 10.1057/palgrave.fsm.4770130

Bollen, K. A., and Noble, M. D. (2011). Structural equation models and the quantification of behavior. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U.S.A. 108, 15639–15646. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1010661108

Brakus, J. J., Schmitt, B. H., and Zarantonello, L. (2009). Brand experience: what is it? How is it measured? Does it affect loyalty? J. Mark. 73, 52–68. doi: 10.1509/jmkg.73.3.052

Brun, I., Rajaobelina, L., Ricard, L., and Berthiaume, B. (2017). Impact of customer experience on loyalty: a multichannel examination. Serv. Ind. J. 37, 317–340. doi: 10.1080/02642069.2017.1322959

Caceres, R. C., and Paparoidamis, N. G. (2007). Service quality, relationship satisfaction, trust, commitment and business-to-business loyalty. Eur. J. Mark. 41, 836–867. doi: 10.1108/03090560710752429

Cadogan, J. W., and Lee, N. (2013). Improper use of endogenous formative variables. J. Bus. Res. 66, 233–241. doi: 10.1016/j.jbusres.2012.08.006

Chang, T.-Y., and Horng, S.-C. (2010). Conceptualizing and measuring experience quality: the customer’s perspective. Serv. Ind. J. 30, 2401–2419. doi: 10.1080/02642060802629919

Chao, P., Fu, H. P., and Lu, L. Y. (2007). Strengthening the quality-loyalty Linkage: the role of customer orientation and interpersonal relationship. Serv. Ind. J. 27, 471–494. doi: 10.1080/02642060701346425

Chaudhuri, A., and Holbrook, M. (2002). Product class effects on brand commitment and brand outcomes: the role of brand trust and brand affect. J. Brand Manag. 10, 33–58. doi: 10.1057/palgrave.bm.2540100

Crosby, L. A., Evans, K. A., and Cowles, D. (1990). Relationship quality in services selling: an interpersonal influence perspective. J. Mark. 54, 68–81. doi: 10.2307/1251817

de la Fuente, J., Verónica Paoloni, P., Vera-Martínez, M. M., and Garzón-Umerenkova, A. (2020). Effect of levels of self-regulation and situational stress on achievement emotions in undergraduate students: class, study and testing. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 17:4293. doi: 10.3390/ijerph17124293

Ferro, C., Padin, C., Svensson, G., and Payan, J. (2016). Trust and commitment as mediators between economic and non-economic satisfaction in manufacturer-supplier relationships. J. Bus. Ind. Mark. 31, 13–23. doi: 10.1108/jbim-07-2013-0154

Flint, D. J., Larsson, E., Gammelgaard, B., and Mentzer, J. T. (2005). Logistics innovation: a customer value-oriented social process. J. Bus. Logistics 26, 113–147. doi: 10.1002/j.2158-1592.2005.tb00196.x

Flint, D. J., Robert, B. W., and Sarah, F. G. (2002). Exploring the phenomenon of customers’ desired value change in a business-to-business context. J. Mark. 66, 102-117.

Fuentes, C. (2015). How green marketing works: practices, materialities and images. Scand. J. Manag. 31, 192–205. doi: 10.1016/j.scaman.2014.11.004

Ganesan, S. (1994). Determinants of long-term orientation in buyer–seller relationships. J. Mark. 58, 1–19. doi: 10.2307/1252265

Garbarino, E., and Johnson, M. S. (1999). The different roles of satisfaction, trust, and commitment in customer relationships. J. Mark. 63, 70–87. doi: 10.2307/1251946

Gentile, C., Spiller, N., and Noci, G. (2007). How to sustain the customer experience:: an overview of experience components that co-create value with the customer. Eur. Manag. J. 25, 395–410.

Hair, J. F. Jr., Sarstedt, M., Ringle, C. M., and Gudergan, S. P. (2017). Advanced Issues in Partial Least Squares Structural Equation Modeling. Thousand Oaks, CA: SAGE publications.

Hair, J. Jr., Black, W., Babin, B., Anderson, R., and Tatham, R. (2010). SEM: An Introduction. Multivariate Data Analysis: A Global Perspective, 7th Edn. New Jersey, NJ: Pearson-Prentice Hall.

Hennig-Thurau, T., and Klee, A. (1997). The impact of customer satisfaction and relationship quality on customer retention: a critical reassessment and model development. Psychol. Mark. 14, 737–764. doi: 10.1002/(sici)1520-6793(199712)14:8<737::aid-mar2>3.0.co;2-f

Holbrook, M. B. (1999). Consumer Value: A Framework for Analysis and Research. New York, NY: Routledge.

Hosany, S., and Witham, M. (2010). Dimensions of Cruisers’ experiences, satisfaction, and intention to recommend. J. Travel Res. 49, 351–364. doi: 10.1177/0047287509346859

Hsieh, Y. C., and Hiang, S. T. (2004). A study of the impacts of service quality on relationship quality in search-experience-credence services. Total Q. Manag. Bus. Excell. 15, 43–58. doi: 10.1080/1478336032000149090

Huber, F., Herrmann, A., and Morgan, R. E. (2001). Gaining competitive advantage through customer value oriented management. J. Consum. Mark. 18, 41–53. doi: 10.1108/07363760110365796

Jin, N., Line, N. D., and Goh, B. (2013). Experiential value, relationship quality, and customer loyalty in full-service restaurants: the moderating role of gender. J. Hosp. Mark. Manag. 22, 679–700. doi: 10.1080/19368623.2013.723799

Jöreskog, K. G., and Sörbom, D. (1993). LISREL 8: Structural Equation Modeling with the SIMPLIS Command Language. Mooresville, IL: Scientific Software.

Kotler, P. (1997). Marketing Management - Analysis Planning, Implementation, and Control, 9th Edn. Englewood Cliffs, NJ: Prentice-Hall.

Kumar, N., Scheer, L. K., and Steenkamp, J. B. (1995). The effects of supplier fairness on vulnerable resellers. J. Mark. Res. 32, 54–65. doi: 10.2307/3152110

Lam, S. Y., Shankar, V., Erramilli, M. K., and Murthy, B. (2004). Customer value, satisfaction, loyalty, and switching costs: an illustration from a business-to-business service context. J. Acad. Mark. Sci. 32, 293–311. doi: 10.1177/0092070304263330

Lemke, F., Clark, M., and Wilson, H. (2011). Customer experience quality: an exploration in business and consumer contexts using repertory grid technique. J. Acad. Mark. Sci. 39, 846–869. doi: 10.1007/s11747-010-0219-0

Lemon, K. N., and Verhoef, P. C. (2016). Understanding customer experience throughout the customer journey. J. Mark. 80, 69–96. doi: 10.1509/jm.15.0420

Lin, J., Wang, B., Wang, N., and Lu, Y. (2014). Understanding the evolution of consumer trust in mobile commerce: a longitudinal study. Inf. Technol. Manag. 15, 37–49. doi: 10.1007/s10799-013-0172-y

Luo, M. M., Chen, J. S., Ching, R. K., and Liu, C. C. (2011). An examination of the effects of virtual experiential marketing on online customer intentions and loyalty. Serv. Ind. J. 31, 2163–2191. doi: 10.1080/02642069.2010.503885

Maklan, S., and Klaus, P. (2011). Customer experience: are we measuring the right things? Int. J. Mark. Res. 53, 771–792. doi: 10.2501/ijmr-53-6-771-792

Marković, S., and Raspor Janković, S. (2013). Exploring the relationship between service quality and customer satisfaction in Croatian hotel industry. Tour. Hosp. Manag. 19, 149–164.

Mathwick, C., Malhotra, N., and Rigdon, E. (2001). Experiential value: conceptualization, measurement and application in the catalog and internet shopping environment. J. Retail. 77, 39–56. doi: 10.1016/s0022-4359(00)00045-2

McDonagh, P., and Prothero, A. (2014). Sustainability marketing research: past, present and future. J. Mark. Manag. 30, 1186–1219. doi: 10.1080/0267257x.2014.943263

McMullan, R., and Gilmore, A. (2003). The conceptual development of customer. loyalty measurement: a proposed scale. J. Target. Meas. Anal. Mark. 11, 230–243. doi: 10.1057/palgrave.jt.5740080

Menon, A., and Menon, A. (1997). Enviropreneurial marketing strategy: the emergence of corporate environmentalism as market strategy. J. Mark. 61, 51–67. doi: 10.2307/1252189

Moliner, M. A., Sánchez, J., Rodríguez, R. M., and Callarisa, L. (2007). Perceived relationship quality and post-purchase perceived value: an integrative framework. Eur. J. Mark. 41, 1392–1422. doi: 10.1108/03090560710821233

Monferrer-Tirado, D., Estrada-Guillén, M., Fandos-Roig, J. C., and Moliner-Tena, M. Á, and Sánchez García, J. (2016). Service quality in bank during an economic crisis. Int. J. Bank Mark. 34, 235–259. doi: 10.1108/ijbm-01-2015-0013

Morgan, R. M., and Hunt, S. D. (1994). The commitment-trust theory of relationship marketing. J. Mark. 58, 20–38. doi: 10.2307/1252308

Olavarría-Jaraba, A., Cambra-Fierro, J. J., Centeno, E., and Vázquez-Carrasco, R. (2018). Analyzing relationship quality and its contribution to consumer relationship proneness. Serv. Bus. 12, 641–661. doi: 10.1007/s11628-018-0362-0

Oliver, R. L. (1997). Satisfaction: A Behavioral Perspective on the Consumer. New York, NY: Irwin/McGraw-Hill.

Palmatier, R. W., Dant, R. P., Grewal, D., and Evans, K. R. (2006). Factors influencing the effectiveness of relationship marketing: a meta-analysis. J. Mark. 70, 136–153. doi: 10.1509/jmkg.70.4.136

Papadas, K. K., Avlonitis, G. J., and Carrigan, M. (2017). Green marketing orientation: conceptualization, scale development and validation. J. Bus. Res. 80, 236–246. doi: 10.1016/j.jbusres.2017.05.024

Pine, B. J., and Gilmore, J. H. (1998). Welcome to the experience economy. Harvard Bus. Rev. 76, 97–105.

Prasad, J. S., and Aryasri, A. R. (2008). Study of customer relationship marketing practices in organized retailing in food and grocery sector in India: an empirical analysis. J. Bus. Perspect. 12, 33–43. doi: 10.1177/097226290801200404

Rauyruen, P., and Miller, K. E. (2007). Relationship quality as a predictor of B-to-B customer loyalty. J. Bus. Res. 60, 21–31. doi: 10.1016/j.jbusres.2005.11.006

Schmitt, B. (1999). Experiential marketing. J. Mark. Manag. 15, 53–67. doi: 10.1362/026725799784870496

Seiders, K., Voss, G. B., Grewal, D., and Godfrey, A. L. (2005). Do satisfied customers buy more? Examining moderating influences in a retailing context. J. Mark. 69, 26–43. doi: 10.1509/jmkg.2005.69.4.26

Singh, J., and Sirdeshmukh, D. (2000). Agency and trust mechanisms in consumer satisfaction and loyalty judgments. J. Acad. Mark. Sci. 28, 150–167. doi: 10.1177/0092070300281014

Slåtten, T., Mehmetoglu, M., Svensson, G., and Svćri, S. (2009). Atmospheric experiences that emotionally touch customers: a case study from a winter park. Manag. Serv. Q. 19, 721–746. doi: 10.1108/09604520911005099

Smith, A. K., and Bolton, R. N. (1998). An experimental investigation of customer reactions to service failure and recovery encounters. J. Serv. Res. 1, 65–81. doi: 10.1177/109467059800100106

Srivastava, M., and Kaul, D. (2016). Exploring the link between customer experience–loyalty–consumer spend. J. Retail. Consum. Serv. 31, 277–286. doi: 10.1016/j.jretconser.2016.04.009

Tsaur, S. H., Chiu, Y. T., and Wang, C. H. (2007). The visitors behavioral consequences of experiential marketing: an empirical study on Taipei Zoo. J. Travel Tour. Mark. 21, 47–64. doi: 10.1300/j073v21n01_04

Verhoef, P. C., Lemon, K. N., Parasuraman, A., Roggeveen, A., Tsiros, M., and Schlesinger, L. A. (2009). Customer experience creation: determinants, dynamics and management strategies. J. Retail. 85, 31–41. doi: 10.1016/j.jretai.2008.11.001

Wu, H. C., and Ai, C. H. (2016). Synthesizing the effects of experiential quality, excitement, equity, experiential satisfaction on experiential loyalty for the golf industry: the case of Hainan Island. J. Hosp. Tour. Manag. 29, 41–59. doi: 10.1016/j.jhtm.2016.05.005

Wu, H. C., and Li, T. (2017). A study of experiential quality, perceived value, heritage image, experiential satisfaction, and behavioral intentions for heritage tourists. J. Hosp. Tour. Res. 41, 904–944. doi: 10.1177/1096348014525638

Wu, H., Cheng, C., Chen, Y., and Hong, W. (2018). Towards green experiential loyalty: driving from experiential quality, green relationship quality, environmental friendliness, green support and green desire. Int. J. Contemp. Hosp. Manag. 30, 1374–1397. doi: 10.1108/ijchm-10-2016-0596

Wu, H. C., Li, M. Y., and Li, T. (2018). A study of experiential quality, experiential value, experiential satisfaction, theme park image, and revisit intention. J. Hosp. Tour. Res. 42, 26–73. doi: 10.1177/1096348014563396

Wulf, K. D., Schroder, G. O., and Lacobucci, D. (2001). Investments in consumer relationships: a corss-country and corss-industry exploration. J. Mark. 65, 33–50. doi: 10.1509/jmkg.65.4.33.18386

Yuan, Y. H. E., and Wu, C. K. (2008). Relationships among experiential marketing, experiential value, and customer satisfaction. J. Hosp. Tour. Res. 32, 387–410. doi: 10.1177/1096348008317392

Zaltman, G., and Wallendorf, M. (1983). Consumer Behavior: Basic Findings and Management Implications. New York, NY: John Wiley & Sons.

Zeithaml, V. A. (1988). Consumer perceptions of price, quality, and value: a means-end model and synthesis of evidence. J. Mark. 52, 2–22. doi: 10.2307/1251446

Keywords: green experiential marketing, green marketing, experiential value, relationship quality, customer loyalty

Citation: Lee T-C and Peng MY-P (2021) Green Experiential Marketing, Experiential Value, Relationship Quality, and Customer Loyalty in Environmental Leisure Farm. Front. Environ. Sci. 9:657523. doi: 10.3389/fenvs.2021.657523

Received: 23 January 2021; Accepted: 25 February 2021;

Published: 28 May 2021.

Edited by:

Faik Bilgili, Erciyes University, TurkeyReviewed by:

Sevda Kuşkaya, Erciyes University, TurkeyAweng Peter Majok Garang, University of Juba, South Sudan

Copyright © 2021 Lee and Peng. This is an open-access article distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution License (CC BY). The use, distribution or reproduction in other forums is permitted, provided the original author(s) and the copyright owner(s) are credited and that the original publication in this journal is cited, in accordance with accepted academic practice. No use, distribution or reproduction is permitted which does not comply with these terms.

*Correspondence: Michael Yao-Ping Peng, s91370001@mail2000.com.tw

†These authors have contributed equally to this work and share first authorship

Tzai-Chiao Lee1†

Tzai-Chiao Lee1†  Michael Yao-Ping Peng

Michael Yao-Ping Peng