- 1The School of Medicine and Manchester Academic Health Sciences Centre, University of Manchester, Manchester, United Kingdom

- 2Department of Endocrinology and Diabetes, Salford Royal Hospital, Salford, United Kingdom

- 3Thyroid Research Group, Division of Infection and Immunity, Cardiff University School of Medicine, Cardiff, United Kingdom

- 4Res Consortium, Andover, United Kingdom

Primary hypothyroidism affects about 3% of the general population in Europe. Early treatments in the late 19th Century involved subcutaneous as well as oral administration of thyroid extract. Until the early 1970s, the majority of people across the world with hypothyroidism were treated with natural desiccated thyroid (NDT) (derived from pig thyroid glands) in various formulations, with the majority of people since then being treated with levothyroxine (L-thyroxine). There is emerging evidence that may account for the efficacy of liothyronine (NDT contains a mixture of levothyroxine and liothyronine) in people who are symptomatically unresponsive to levothyroxine. While this is a highly selected group of people, the severity and chronicity of their symptoms and the fact that many patients have found their symptoms to be alleviated, can be viewed as valid evidence for the potential benefit of NDT when given after careful consideration of other differential diagnoses and other treatment options.

Introduction

Primary hypothyroidism affects about 3% of the general population in Europe (1). Early treatments in the late 19th Century involved subcutaneous as well as oral administration of thyroid extract (2, 3). Until the early 1970s, the majority of people with this condition were treated with natural desiccated thyroid (NDT) (derived from pig thyroid glands) in various formulations (4), with the majority of people since then being treated with levothyroxine (L-thyroxine).

It is reported that up to 10% of treated diagnosed hypothyroid individuals report impaired quality of life, despite achieving serum free thyroxine and thyroid stimulating hormone (TSH) levels within the laboratory reference range and ideally in the ideally in the lower half of the reference range (5). A proportion of people with hypothyroidism who are seemingly treatment resistant as described, are prescribed liothyronine (L-tri-iodothyronine), usually in addition to levothyroxine and occasionally as monotherapy but some do prefer NDT (6).

From the early 1890s through the mid-1970s, desiccated thyroid was the preferred form of therapy for hypothyroidism. In 1965, approximately 4 of every 5 prescriptions for thyroid hormone in the USA were for natural thyroid preparations (4). Concerns about inconsistencies in the potency of these tablets arose after the discovery that some contained anywhere from double to no detectable metabolic activity (7). It was not until 1985 that the revision of the U.S. Pharmacopeia standard from iodine content to L-liothyronine Tt3)/L-thyroxine (T4) content resulted in stable potency after earlier concerns (8), but by then the move to levothyroxine was nearly complete in many countries so that levothyroxine largely replaced NDT. With its more favorable pharmacokinetics allowing for once daily dosing and clinical trial evidence (9), levothyroxine monotherapy has prevailed as the treatment of choice for primary hypothyroidism.

In some cases, seemingly levothyroxine unresponsive individuals with hypothyroidism, are prescribed a Natural Desiccated Thyroid (NDT) preparation such as Armour Thyroid® (4) or ERFA Thyroid®. Other preparations are NatureThroid, WP Thyroid and NP Thyroid (10). They contain a mixture of levothyroxine and liothyronine in a fixed ratio (although this ratio does vary slightly between batches). There is a bovine thyroid derived NDT preparation (11) which can be taken by individuals who for religious or cultural reasons do not eat pork. The NDT preparations available at the time of writing are given in Table 1.

Over the last four decades, only a small proportion of clinicians in the United Kingdom in primary care and in specialist endocrinology clinics have prescribed NDT (12). However it remains an agent that is prescribed in the National Health Service (NHS) in England. We previously reported that 436 individuals in 2018/2019. were prescribed NDT in England by their general practitioners (GPs) across 382 general practices (13). In 2022 an estimated 337 individuals were prescribed NDT in general practice in England. However this does not take account of hospital or private prescriptions. In the United States of America (USA), NDT prescribing is much more prevalent by at least a factor of 10 compared with the UK.

The UK National Institute for Health and Care Excellence (NICE), in its clinical guideline on thyroid disease (14), recommended that further research should be undertaken on the clinical and cost effectiveness of liothyronine/levothyroxine combination therapy compared with levothyroxine alone for people with hypothyroidism whose symptoms have not responded sufficiently to levothyroxine alone. In the absence of such evidence, clinicians have had to take a pragmatic approach in relation to the management of patients who report continuing symptoms, in spite of apparent adequate thyroid hormone replacement, with some prescribing NDT as a less costly alternative to liothyronine (13, 15). The average Cost of NDT in 2016 was £207/prescription with growth by 220% to £440 in 2022 still below liothyronine but up on 2016 levels, while total annual prescriptions fell by 44% from 4,257 in 2016 to 2,384 in 2022. However this does not take account of hospital or private prescriptions.

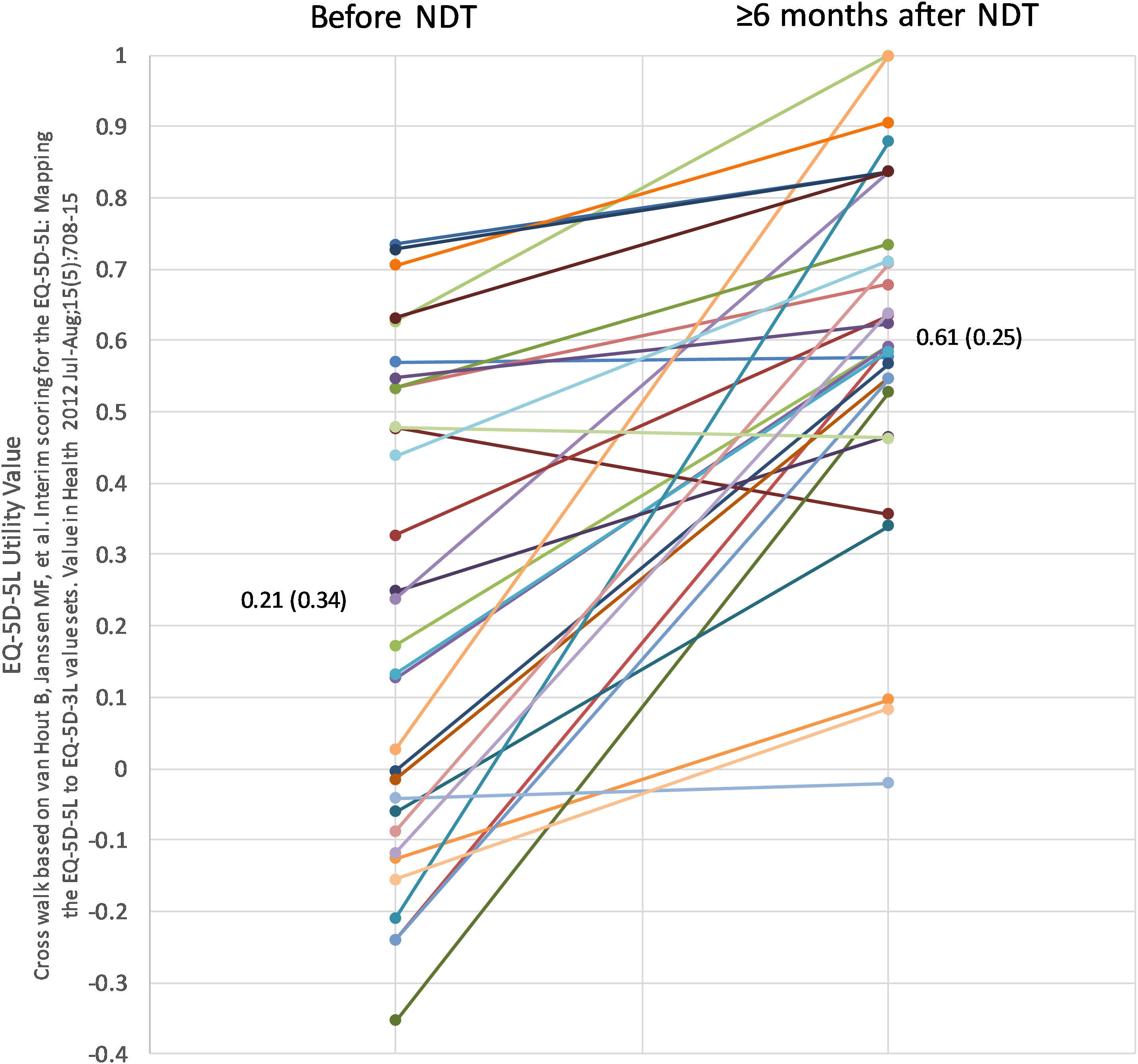

In our recent case series (16) it was reported that significant benefit was experienced by people who by nature of their lack or response to levothyroxine were treated with NDT. The authors noted that the majority of patients found these symptoms to be alleviated and suggested that this could be viewed as robust evidence for the potential benefit of NDT. Notably a significant associated benefit, as measured both by EQ-5D-5L utility scores and ThyPRO scores was seen in people on NDT, as measured both by the EQ-5D-5L and ThyPRO ratings (Figure 1).

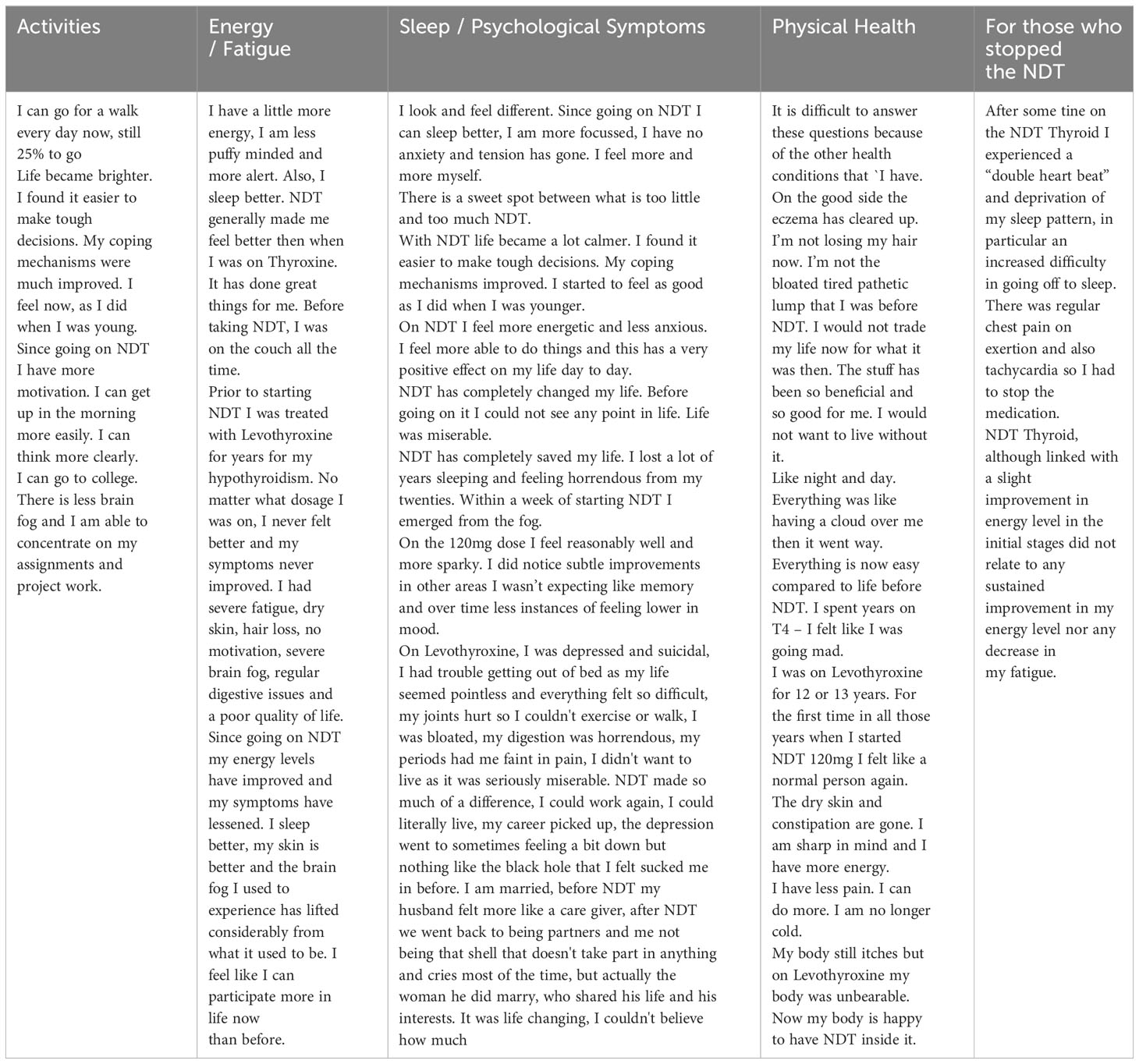

Individual descriptions of the response to NDT in relation to improvement in quality of life and reduction in symptoms were as follows in relation to the lived narrative.

As a result of NDT being around for so long it did not ever need to go through the licensing process in North America – it was classed as a ‘grandfathered drug’ (6). The Food and Drug Administration (FDA) allows some unapproved prescription drugs to be lawfully marketed if they meet the criteria of ‘generally recognized as safe and effective’ (GRASE) or grandfathered (17). Grandfathered drugs are those that were already marketed prior to 1938 and were exempt from changes to their labeling or safety studies under the Federal Food Drug and Cosmetics Act (FFDCA) (17). These drugs have not been formally approved by the FDA. NDT is prescribed as part of usual care in both general practice and specialist settings in many countries.

Current guidelines do not endorse the use of NDT but many people across the world do take it and report great benefit. It should be pointed out that thyrotoxic symptoms and some cases of thyroid storm have been reported during the inappropriate use of thyroid hormone extracts including NDT (18). In the United Kingdom and Eire NDT must be prescribed by a health care practitioner and are not obtainable over the counter. In other countries NDT can be bought ‘over the counter’ in person or on-line.

There is emerging evidence that may account for the efficacy of liothyronine (NDT contains a mixture of levothyroxine and liothyronine) in people who are symptomatically unresponsive to levothyroxine (19). Free T3 is the endogenous thyroid hormone, converted from Free T4 predominantly by local de-iodination in tissues. Increased free T4 levels, as seen with levothyroxine therapy alone, appear to inhibit local deiodination except in the pituitary, so that levothyroxine monotherapy may result in TSH (20) inhibition while reducing thyroid bioavailabity in other tissues.

Polymorphisms in the genetic coding of the deiodinase-2 (DIO2) enzyme, present in 13% of the population, have the potential to reduce T3 levels in many tissues, including the brain, without affecting serum levels (21). This may represent a pharmacogenetic component in those who are non-responsive to levothyroxine (22).

The body of opinion continues to be divided as to whether any other option than levothyroxine should be pursued in levothyroxine unresponsive individuals, with NDT among these other options available. Two randomized double blind controlled trials (RCTs) have compared NDT with levothyroxine. In the RCT reported by Hoang et al. (19), NDT therapy did not result in a significant improvement in quality of life. However NDT was associated with a degree of weight loss and nearly half (48.6%) of the study participants expressed preference for NDT over levothyroxine. (48.6%) Those who preferred NDT lost 4lb during the treatment, and their subjective symptoms were significantly better while taking DTE as measured by the general health questionnaire-12 (23) and a bespoke thyroid symptom questionnaire (24). In a subsequent study by the same group involving a comparison between levothyroxine, levothyroxine+ liothyronine and NDT, subgroup analyses of the 1/3 most symptomatic patients on levothyroxine revealed strong preference for treatment containing liothyronine (levothyroxine+liothyronine and NDT), which reduced symptomatology and improved performance on several scales (25).

The American Thyroid Association concluded in 2014 that there is a role for long-term outcome clinical trials testing combination therapy or thyroid extracts (26). We accept that there are some who take a different view on the prescribing of NDT to people with levothyroxine unresponsive hypothyroidism, for example by Coutinho et al. in 2018 (27) – they stated that due to the ‘lack of standardization’ in the liothyronine content, the use of ArmourThyroid® should be avoided. However, it should again be pointed out that since 1985 the formulation of clinician prescribed NDT has been considered reliable (8), contrary to what is believed by some to be the case. Nevertheless the precise composition of NDT thyroid does very slightly over time, given that this is a biological preparation.

In countries like the UK, where liothyronine prescription costs run at a premium (although they have reduced in recent years), NDT may be considered as a lower dose alternative to combination treatment with levothyroxine and liothyronine. Nevertheless it should not be prescribed in anyone with a history of diagnosed cardiac dysrhythmia.

Some clinicians take a different view on the matter of alternative treatment of levothyroxine (28). The reduction it symptoms and improvement in quality of life, as evidenced in our study by the change in scores on the ThyPro and EQ5D5L (29, 30) scales provide objective evidence of benefit and although very much a minority player in terms of numbers of prescriptions in the UK (30) and in some other countries, it is still seen by some clinicians as an agent that be of benefit in treating people with ongoing symptoms of hypothyroidism in spite of levothyroxine treatment. Furthermore individual patient preference in relation to medication that most people with hypothyroidism have to take lifelong should be considered when making prescribing choices.

For initiation of NDT, the therapy is usually instituted using low doses, with increments which depend on the cardiovascular status of the patient. The usual starting dose is 30 mg of eg Armour Thyroid (31) with increments of 15 mg every 2 to 3 weeks. A lower starting dosage, 15 mg/day, is recommended in patients with long-standing myxedema, particularly if cardiovascular impairment is suspected, in which case extreme caution is recommended. The appearance of angina is an indication for a reduction in dosage. Most patients require 60 to 120 mg/day. Failure to respond to doses of 180 mg suggests lack of concordance or malabsorption. Maintenance dosages 60 to 120 mg/day usually result in normal serum T4 and T3 levels. Adequate therapy usually results in normal TSH and T4 levels after 2 to 3 weeks of therapy.

Individual descriptions of the response to NDT in relation to improvement in quality of life and reduction in symptoms (Table 2) have validity in a clinical context. The potential beneficial effects of combination treatment with levothyroxine and liothyronine (with an optimum ratio of LT4 to LT3) cannot be compared to treatment with NDT in hypothyroid patients; the latter containing a slightly different proportion of LT3 and LT4 vs the physiological ratio. We need large well-designed RCTs to identify which individuals could benefit from NDT compared to LT4 monotherapy.

Nevertheless, while NDT is not perfect in terms of the ratio of liothyronine to levothyroxine it can offer a ‘lifeline’ to people who may for many years have experienced debilitating symptoms of levothyroxine unresponsiveness who are not able to access combination prescribed LT4 and LT3.

Conclusion

Significant benefit is experienced by people who by nature of their lack or response to levothyroxine have been treated with NDT. While this is a highly selected group of people, the severity and chronicity of their symptoms and the fact that many patients have found their symptoms to be alleviated, can be viewed as valid evidence for the potential benefit of NDT when given after careful consideration of other differential diagnoses and other treatment options.

Author contributions

AH: Conceptualization, Investigation, Methodology, Resources, Visualization, Writing – original draft, Writing – review & editing. PT: Conceptualization, Investigation, Software, Visualization, Writing – original draft, Writing – review & editing. LP: Conceptualization, Formal Analysis, Investigation, Methodology, Writing – original draft, Writing – review & editing. MS: Validation, Visualization, Writing – original draft, Writing – review & editing. CD: Conceptualization, Validation, Writing – original draft, Writing – review & editing.

Funding

The author(s) declare that no financial support was received for the research, authorship, and/or publication of this article.

Conflict of interest

The authors declare that the research was conducted in the absence of any commercial or financial relationships that could be construed as a potential conflict of interest.

Publisher’s note

All claims expressed in this article are solely those of the authors and do not necessarily represent those of their affiliated organizations, or those of the publisher, the editors and the reviewers. Any product that may be evaluated in this article, or claim that may be made by its manufacturer, is not guaranteed or endorsed by the publisher.

References

1. Taylor PN, Albrecht D, Scholz A, Gutierrez-Buey G, Lazarus JH, Dayan CM, et al. Global epidemiology of hyperthyroidism and hypothyroidism. Nat Rev Endocrinol (2018) 14:301–16. doi: 10.1038/nrendo.2018.18

2. Murray GP. Note on the treatment of myxoedema by hypodermic injections of an extract of the thyroid gland of sheep. BMJ. (1891) 2:796–10. doi: 1136/bmj.2.1606.796

3. Fox EL. A case of myxoedema treated by taking extract of thyroid by mouth. BMJ (1892) 2:941. doi: 10.1136/bmj.2.1661.941

4. Kaufman SC, Gross TP, Kennedy DL. Thyroid hormone use: trends in the United States from 1960 through 1988. Thyroid. (1991) 1:285–91. doi: 10.1089/thy.1991.1.285

5. Pearce SH, Brabant G, Duntas LH, Monzani F, Peeters RP, Razvi S, et al. ETA guideline: management of subclinical hypothyroidism. Eur Thyroid J (2013) 2(4):215–28. doi: 10.1159/000356507

6. McAninch EA, Bianco AC. The history and future of treatment of hypothyroidism. Ann Intern Med (2016) 164:50–6. doi: 10.7326/M15-1799

7. Braverman LE, Ingbar SH. Anomalous effects of certain preparations of desiccated thyroid on serum protein-bound iodine. N Engl J Med (1964) 270:439–42. doi: 10.1056/NEJM196402272700903

8. Mangieri CN, Lund MH. Potency of United States Pharmacopeia dessicated thyroid tablets as determined by the antigoitrogenic assay in rats. J Clin Endocrinol Metab (1970) 30:102–4. doi: 10.1210/jcem-30-1-102

9. Smith RN, Taylor SA, Massey JC. Controlled clinical trial of combined triiodothyronine and thyroxine in the treatment of hypothyroidism. Br Med J (1970) 17(4):145–8. doi: 10.1136/bmj.4.5728.145

10. Mitchell AL, Hickey B, Hickey JL, Pearce SH. Trends in thyroid hormone prescribing and consumption in the UK. BMC Public Health (2009) 9:132. doi: 10.1186/1471-2458-9-132

11. Jackson IM, Cobb WE. Why does anyone still use desiccated thyroid USP? Am J Med (1978) 64:284–8. doi: 10.1016/0002-9343(78)90057-8

12. Saravanan P, Chau WF, Roberts N, Vedhara K, Greenwood R, Dayan CM. Psychological well-being in patients on 'adequate' doses of l-thyroxine: results of a large, controlled community-based questionnaire study. Clin Endocrinol (Oxf). (2002) 57:577–85. doi: 10.1046/j.1365-2265.2002.01654.x

13. Stedman M, Taylor P, Premawardhana L, Okosieme O, Dayan C, Heald AH. Liothyronine and levothyroxine prescribing in England: A comprehensive survey and evaluation. Int J Clin Pract (2021) 75(9):e14228. doi: 10.1111/ijcp.14228

14. NICE. Available at: https://www.nice.org.uk/guidance/indevelopment/gid-ng10074 (Accessed 2 November 2020).

15. Stedman M, Taylor P, Premawardhana L, Okosieme O, Dayan C, Heald AH. Trends in costs and prescribing for liothyronine and levothyroxine in England and Wales 2011-2020. Clin Endocrinol (Oxf). (2021) 94(6):980–9. doi: 10.1111/cen.14414

16. Heald AH, Premawardhana L, Taylor P, Okosieme O, Bangi T, Devine H, et al. Is there a role for natural desiccated thyroid in the treatment of levothyroxine unresponsive hypothyroidism? Results from a consecutive case series. Int J Clin Pract (2021) 75(12):e14967. doi: 10.1111/ijcp.14967

17. Available at: https://www.fda.gov/drugs/enforcement-activities-fda/unapproved-drugs.

18. Jha S, Waghdhare S, Reddi R, Bhattacharya P. Thyroid storm due to inappropriate administration of a compounded thyroid hormone preparation successfully treated with plasmapheresis. Thyroid. (2012) 22:1283–1286. doi: 10.1089/thy.2011.0353

19. Hoang TD, Olsen CH, Mai VQ, Clyde PW, Shakir MK. Desiccated thyroid extract compared with levothyroxine in the treatment of hypothyroidism: a randomized, double-blind, crossover study. J Clin Endocrinol Metab (2013) 98:1982–90. doi: 10.1210/jc.2012-4107

20. Christoffolete MA, Ribeiro R, Singru P, et al. Atypical expression of type 2 iodothyronine deiodinase in thyrotrophs explains the thyroxine-mediated pituitary thyrotropin feedback mechanism. Endocrinology (2006) 147(4):1735–43. doi: 10.1210/en.2005-1300

21. Castagna MG, Dentice M, Cantara S, Ambrosio R, Maino F, Porcelli T, et al. DIO2 thr92Ala reduces deiodinase-2 activity and serum-T3 levels in thyroid-deficient patients. J Clin Endocrinol Metab (2017) 102:1623–30. doi: 10.1210/jc.2016-2587

22. Panicker V, Saravanan P, Vaidya B, Evans J, Hattersley AT, Frayling TM, et al. Common variation in the DIO2 gene predicts baseline psychological well-being and response to combination thyroxine plus triiodothyronine therapy in hypothyroid patients. J Clin Endocrinol Metab (2009) 94:1623–9. doi: 10.1210/jc.2008-1301

23. McDowell I, Newell C. The general health questionnaire. Measuring health. A guide to rating scales and questionnaires. 2nd ed. New York, NY: Oxford University Press (1996).

24. Clyde PW, Harari AE, Getka EJ, Shakir KM. Combined levothyroxine plus liothyronine compared with levothyroxine alone in primary hypothyroidism: a randomized controlled trial. JAMA (2003) 290:2952–8.

25. Shakir MKM, Brooks DI, McAninch EA, Fonseca TL, Mai VQ, Bianco AC, et al. Comparative effectiveness of levothyroxine, desiccated thyroid extract, and levothyroxine+Liothyronine in hypothyroidism. J Clin Endocrinol Metab (2021) 106:e4400–13.

26. Jonklaas J, Bianco AC, Bauer AJ, Burman KD, Cappola AR, Celi FS, et al. Guidelines for the treatment of hypothyroidism: prepared by the American Thyroid Association task force on thyroid hormone replacement. Thyroid. (2014) 24:1670–751.

27. Coutinho J, Field JB, Sule AA. Armour® Thyroid rage - A dangerous mixture. Cureus. (2018) 10:e2523.

28. Watt T, Bjorner JB, Groenvold M, Rasmussen AK, Bonnema SJ, Hegedüs L, et al. Establishing construct validity for the thyroid-specific patient reported outcome measure (ThyPRO): an initial examination. Qual Life Res (2009) 18:483–96.

29. Rabin R, de Charro F. EQ-5D: a measure of health status from the EuroQoL Group. Ann Med (2001) 33:337–43. doi: 10.3109/07853890109002087

30. Available at: https://digital.nhs.uk/data-and-information/publications/statistical/practice-level-prescribing-data (Accessed 31 July 2023).

31. Available at: https://www.drugs.com/pro/armour-thyroid.html (Accessed 30 July 2023).

Keywords: hypothyroidism, treatment unresponsive, NDT, liothyronine, cost

Citation: Heald AH, Taylor P, Premawardhana L, Stedman M and Dayan C (2024) Natural desiccated thyroid for the treatment of hypothyroidism? Front. Endocrinol. 14:1309159. doi: 10.3389/fendo.2023.1309159

Received: 07 October 2023; Accepted: 06 December 2023;

Published: 08 January 2024.

Edited by:

Terry Francis Davies, Icahn School of Medicine at Mount Sinai, United StatesReviewed by:

Bernadette Biondi, University of Naples Federico II, ItalyCopyright © 2024 Heald, Taylor, Premawardhana, Stedman and Dayan. This is an open-access article distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution License (CC BY). The use, distribution or reproduction in other forums is permitted, provided the original author(s) and the copyright owner(s) are credited and that the original publication in this journal is cited, in accordance with accepted academic practice. No use, distribution or reproduction is permitted which does not comply with these terms.

*Correspondence: Adrian H. Heald, adrian.heald@manchester.ac.uk

Adrian H. Heald

Adrian H. Heald Peter Taylor

Peter Taylor Lakdasa Premawardhana

Lakdasa Premawardhana Mike Stedman4

Mike Stedman4 Colin Dayan

Colin Dayan