Historical maps as a neglected issue in history education. Students and textbooks representations of territorial changes of Spain and Argentina

- 1National Council of Scientific and Technical Research (CONICET) – FLACSO-Argentina and National University of La Plata, La Plata, Argentina

- 2Autonoma University of Madrid, Madrid, Spain

- 3Universidad Autónoma de Madrid, España and FLACSO-Argentina, Madrid, Argentina

In the last years, history education has become a highly developed field, which is receiving considerable attention not only from educators but also from historians, philosophers of history, and social scientists in general. In this vein, seminal empirical and theoretical papers have focused on how history is taught to students and what are the different abilities that should be developed with the end to critically understand historical processes. These abilities are related to key concepts in the field such as historical thinking, historical consciousness, and historical culture. The aim of this paper is to focus on a matter not much considered in any of these approaches. This is to say, “where” the historical processes occurred. Usually the “where” implies a specific territory that is under dispute. In this vein, territories and their transformation through different time periods are represented by historical maps reproduced in atlas and textbooks. But these representations could have several bias and also tend to provide a number of incomplete ideas among the students and citizens in general. In relation to this, it is necessary study not only the features of historical maps but, also, how students appropriate them. This appropriation could be influenced by an essentialist view of the nation through historical master narratives. This is what we have found in our initial empirical studies in Spain and Argentina. Additional empirical studies are needed to improve history education studies from the point of view of the development of historical thinking and historical consciousness taking into account how historical maps and territorial changes are represented by both students and textbooks.

1 Introduction

In the last decades, there has been a considerable development in research on history education. Some works have referred to the great number of scientific studies under the term History Education that have been published in the last 15 years (Epstein and Salinas, 2018). On the other hand, a great number of the research from this field are intended to design and apply instructional strategies not just to transmit historical facts and dates, but also to analyse how encourage the development of historical thinking (Peck and Seixas, 2008; Lévesque, 2011; Seixas and Morton, 2013).

Works on historical thinking intend mainly to be a reaction against traditional history education that places the student in a passive position. According to this approach, the student must learn, usually by rote memory, facts, dates, and concepts about the past, as well as a given historical master narratives they must internalize. In opposition to this, the new approach proposes a more active history education that incorporates learning second order concepts, which articulate the historical thinking and mirror historian’s procedures to produce narratives about the past (Van Boxtel and van Drie, 2018; Thorp and Persson, 2020). From this new approach, historical knowledge is understood not as a mere description of what happened in the past, but as something that also incorporates the knowledge of the processes from which what happened in the past is interpreted and understood (Lee, 2005). The past is qualitatively different from the present and requires a specific methodology of history to be interpreted and understood, in a way historians do (Wineburg, 2001). To this end, it is necessary to apply the second order concepts or the “historical thinking concepts” (Seixas, 2017, p. 597), like historical significance, primary source evidence, continuity and change, cause and consequence, historical perspective, or the ethical dimension on the past (Seixas, 2004, 2017; Seixas and Morton, 2013).

The two approaches above – traditional and new – correspond to the distinction established between the romantic and enlightened objectives present in the teaching of history (Carretero, 2011). A teaching of history with romantic objectives has a more social character and tries to promote in the students the national identity from a positive assessment of the past, the present and the future of the national group; from a positive assessment of the political evolution of the country; and from the identification with the facts and characters of the past. However, a historical education with enlightened objectives, more focused on historiography and critical rationality, tries to favor in students the complex understanding of the past and the development of historical thinking. All of this from the knowledge of historical periods; from the understanding of historical causality; from historical consciousness and from an active approach to the methodology used by historians. Although the romantic and enlightened objectives often coexist in historical education, nevertheless, the romantics have been predominant from the late nineteenth century until the 70’s in which the enlightened objectives begin to receive attention. Despite this, the presence of romantic objectives for identity purposes in the teaching of history in many countries is still very noteworthy (Carretero, 2011; Berger, 2012).

The historical knowledge that is taught and learned in school contexts is articulated around narratives, that is, schemes of representation of the past that allow to organize in an integrated whole a group of interrelated facts (Wertsch, 1998, 2002). In traditional romantic history teaching, students do not necessarily learn historical thinking, as they reproduce and internalize an already elaborated master narrative about the nation. This master narrative is a cultural tool that incorporates information from a given community and guides how to think and act to be a good member of that community (McLean and Syed, 2015). National master narratives create a cohesive community of understanding from a common interpretation of the past that provides to the one who adopts it with a sense of belonging to the group, as well as of past and shared future perspective (Wertsch, 2018). This narrative gives meaning to human action and national identity (Wertsch, 2021). The national master narrative is not only present in the teacher’s discourse, but also in educational resources, such as textbooks (Alridge, 2006); in school and extracurricular activities, such as reenactments (Carretero et al., 2022); and in other products and cultural and institutional contexts of the community (Wertsch, 2021). The fundamental point is that the already elaborated national master narrative that students must internalize simplifies the interpretation of the past, denies students a complex understanding of it (Alridge, 2006), and prevents students from developing critical rationality and historical thought.

However, in the teaching of history for enlightened purposes students generate actively narratives and construct them from historical thinking, working, for example, on different narratives of different social groups, on sources and evidence, on causes and consequences, as historians do. The construction of narratives is central to historical knowledge and, therefore, narratives must receive greater attention in the models of historical thinking (Zajda, 2022). The narrative about the nation and about the national territory varies depending on the approach from which the teaching of history is undertaken, which can be romantic or enlightened (López et al., 2015; Rodríguez-Moneo and López, 2017).

In that way, an element present in historical master narratives is the territory. In narratives, the territory can either be the place where historical events take place, or a land wanted by the nation that has been conquered or taken by another group and is intended to be recovered. In this sense, the knowledge of the territory where events occur provides important information to understand and analyse the outcomes (Bednarz et al., 2006; Bednarz, 2016). Even more, the territory is transformed because of human actions and, in this vein, it helps us understand better changes in society and history itself. However, despite the central position of the territory for historical master narratives, we think that its relevance to understand the past has not always been properly appreciated in history education research. Although in recent years there have been several studies reflecting on the importance of historical maps in history education, they have underestimated students understanding of the place where such historical events took place and how students represent the national territory and its transformations in the past (Carretero, 2018). In this sense, we think that it is necessary to do more research on the features of historical maps that go with historical master narratives and are used to represent the territory in which the events occurred, or how events have transformed the territory.

To this end, in this paper and within the framework of research in history education, we will firstly consider the importance of reflecting on “where” historical processes took place and how are they represented in historical maps. Secondly, we will analyze the features of cartographic images used at school to represent national historical processes. Then, we will present data from our research in Argentina and Spain about how students represent the territory in the past and its transformations when they produce a historical national narrative. Finally, we will present some considerations about the importance of working with historical maps at school, to encourage students to develop a historical thinking about cartographic images.

2 School historical maps and changes in the territory

As we have mentioned above, the relationship between the territory and events from the past is bidirectional. On one side, the territory has a great value to explain the facts that have occurred in it; on the other side, the events from the past transformed the territory. Thus, when a historical process takes place on a certain space, the territory can be a key factor in the course of events, and also, it may be transformed as a consequence of the events. For example, after the two World Wars, or after the fall of the Berlin Wall, some national territories and, thus, their representations in maps had changed drastically. Even more, in some cases as Poland and Korea the national territory changed dramatically after foreign invasions. In the case of the first by Germany and USRR and in the case of the latter by China and Japan. In the same way, after independence wars in the 19th century, the maps of America were considerably changed. Several state units which did not exist before independence events appeared. In this sense, it should also be observed that after certain historical events, many states around the world have changed their frontiers through the passing of time. In the classroom, one of the sources that can help students understand these transformations are historical maps. A historical map is defined as a group of cartographic representations designed in the present in order to represent the territory of the past and the changes it has undergone. In addition, these maps tend to appear in student’s textbooks and atlases (Kamusella, 2010).

The maps students use in class, either printed or digital, are external visual–spatial representations and they are used to create an internal representation in the students in an analogous format. The analogous representational format is combined with the historical information students usually incorporate in a propositional format (Aparicio Frutos and Rodríguez-Moneo, 2015), derived from the historical information in textbooks and in their teacher’s speech.

In general, historical maps used at school are divided by geographical or political borders to show political, social, cultural, and economic activities. These borders help to develop the identity of the people included within those limits and, at the same time, it excludes everyone who is a foreigner in that limited territory (Agnew, 2008). The territories bounded by the borders are linked to the nation-state and the maps about the nation are very present both inside and outside the school, so that students develop their national identity linked to the territory of the nation reproduced on the map and tend to reproduce essentialist biases about the national space, often induced by school materials, as will be seen below.

As we mentioned above, maps are associated to master narratives, and they help understand them better (Caquard, 2013). It could be said that historical maps play a key role in the history teaching field, together with the narratives: they actively help to produce an effect of reality and credibility in the master narratives they go with. However, in the same way, maps not only help to legitimize the content of narratives, but they also create and foster national historical narratives (Craib, 2002). For example, after Iraq troops invaded Kuwait in 1990, the government of that country produced two atlases to shatter Iraq government’s intentions to reclaim Kuwait as a part of their territory (Culcasi, 2011). These atlases included maps from the 19th century where Kuwait was a state unit independent from the Mesopotamia Region. This example shows how historical maps interact with national master narratives. Maps are a guarantee of the veracity of the narratives, and they carry national narratives that reflect a certain group’s perspective about the space and hide other narratives and cartographic images they would be in conflict with. Even more, after the decolonization period in the 19th and 20th centuries, many American nation states produced their own national historical maps in order to delete their colonial past and to highlight their existence as an entity prior to the colonization period (Dym and Offen, 2011).

As well as with master narratives, maps can be used according to the principles of traditional or romantic history teaching (Carretero, 2011). From this approach, the information included in the historical map and the transformations in the territory are meant to be learned just as they appear in the representation, learning dates and events by memory, and justifying them based on the present political map, on the national identity, and on the master narrative it is included in. Even the sequence in which maps are presented in a textbook or a historical atlas may be a product of a narrative web used to legitimize certain actions through the visualization of the space involved in the national narratives (Herb, 2004). However, it is also possible to use maps with a more Enlightened approach and based on historical thinking. In this case, the historical map is considered as a complex document that may trigger questions for reflection and critical thinking (LeBlanc, 2016). In this sense, maps are considered a source to be analyzed, that can be compared with other maps or sources; a source from which we can explore the historical significance of the events that can be inferred from the map; their causes and consequences; continuity and change in time. It can also be used to analyze the historical perspective and the relationship between past events and present reality, and a projection of the future.

3 Historical representation of the national territory

Let us mention a specific anecdote, which could be useful to describe lay representations about the national territory in the past. Some years ago, in a documentary about Arizona Border Recon1 group, which can be seen on internet,2 one member of the group said they defend the borders because without them, they would be lost as a nation. For him, and according to his words, the disappearance of the frontier would imply a loss of sovereignty, of identity, and of their culture. The interviewee seems to confuse the concepts of territory, sovereignty, identity, and even culture in his speech. On the other hand, it is worth mentioning that the present territory of Arizona was added formally to the United States territory in 1848, because of the Guadalupe-Hidalgo Treat, that ended the war between Mexico and the United States. This shows the importance of considering how the territory is represented in historical maps and the transformations it undergoes. This analysis may help us understand the importance of advocating for the development of historical thinking in school contexts, so necessary and relevant now that we are witnessing several territorial and migration conflicts.

In this vein, it would be interesting to ask ourselves: How was this border established? Which are the causes that led to its constitution? Has the border line dividing Mexico and the United States always been there, or has it been changing for a long time? Even when the answers to these questions apply specifically to the territorial history of the United States of America, we deem it necessary to make these questions and to encourage our students to think about them in the classroom when we are teaching the configuration of the national territory, as they can lead students to a better understanding of the relationship between past and present.

As a consequence of human actions, the borders of national territories change. However, we think that school historical maps do not show the complexity of these transformations and they tend to show an atemporal representation of the territory. Figure 1 is an example of the historical maps we can usually find in textbooks when the territorial transformations in the United States are made explicit. The interest on the contents of historical maps is because they are a graphic representation used to make the contents of the master narrative more concrete in school contexts, either through textbooks, historical master narratives or some other source (Pérez-Manjarrez and Carretero, 2021).

Figure 1. Historical territorial expansion of the United States of America from Carretero (2018). Available in https://vividmaps.com/the-united-states-of-america/.

As we can see, in the previous map, the current limits and state borders are mixed with the territorial transformations that took place during the 19th century. The map shows the expansion of the territory of the United States and each color represents a stage in the expansion process. However, each of those processes was carried out through specific actions against different peoples and the territory changed after each process. Now, in the historical map it seems that this is a logical evolution as the transformations are represented on the current map, as if the current limits of the United States already existed in those days, and this makes it more difficult for students to understand the differences in each historical moment. We think this confusion may be based on the essentialist conceptions students develop about the national territory, as we will see below.

On the other hand, in the different periods the map refers to, many of the states that form the United States today did not exist, not politically, nor territorially. However, they are mentioned in the map and, hence, made concrete providing a sense of permanence in time. The map not only shows the idea that the United States existed with its current external limits, but also with it current political and administrative division. Thus, the cartographic image mixes past and present, but it also implies that the national territory has maintained its essence, as it is presented as an unmodified space despite the transformations it pretends to show. These features of historical maps are not only observed when teaching the expansion of the American territory. In our research, we have found similar patterns in the historical maps of Argentina (Parellada et al., 2020) and Mexico (Pérez-Manjarrez and Carretero, 2021). In the next sections, we will analyze the representation of Argentina’s territorial expansion in the historical maps used in school contexts.

4 Historical maps in schools in Argentina and the territorial evolution

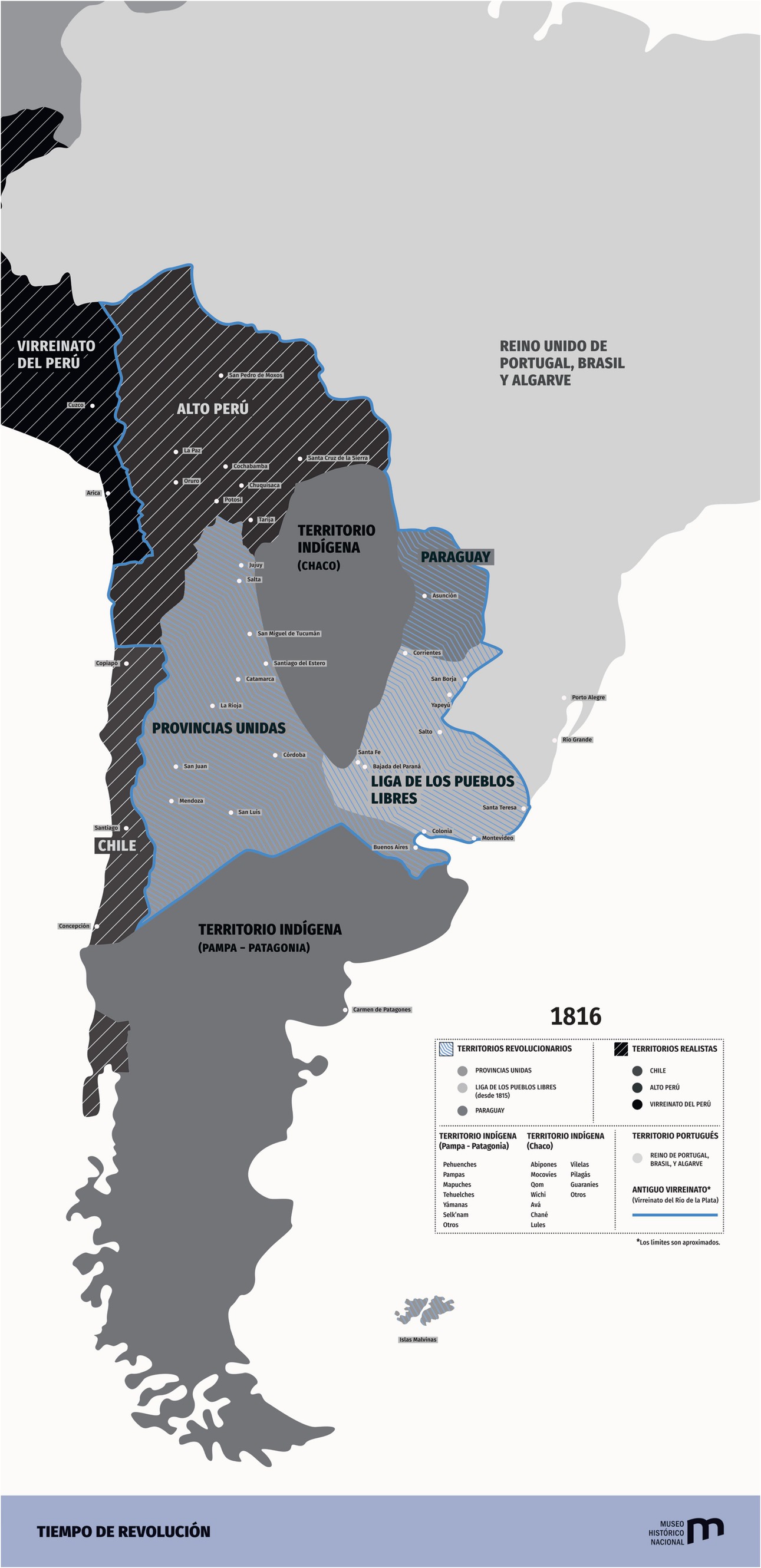

Argentina became an independent state on July 9th, 1816. However, in those days, the new nation state had a different territory and a different political and administrative organization (Lois, 2014). After de afore mentioned date and over more than 40 years, there were several civil wars to define what the political organization of the new state would be. Finally, once the civil wars ended by the end of the 19th century, and politically organized as a nation state, several military campaigns, known as the Conquest of the Desert (1878–1885) to expand the territory were undertaken. These campaigns were done in order to conquer Patagonia lands, at the south of the line of latitude 42, which were at that moment under the control of the aboriginal peoples (Lois, 2014). In other words, until 1885, when the Conquest of the Desert ended, Argentina did not have any sovereign right over the lands of Patagonia. Even more, there was an international dispute over those territories with Chile, country that gave up its rights on the territory in 1881, when they signed a territorial treat with Argentina (Orrego Luco, 1902). In Figure 2, we can see a map exhibited nowadays in the National Historical Museum of Argentina in 2022, which illustrates the territorial situation of the different political units that were being established as a consequence of the independence wars, in the southern part of America. Specifically, in the map the parts named Indigenous Territory [Territorio Indígena] show a part of the current Argentinian territory, which was not colonized until the end of 19th century. As a matter of fact, this territory was not part of the Spanish Viceroy of the River Plate, by 1810–6 when the independence of Argentina as a nation started. As can be seen in the map, this process of independence took place at the same time in two different territories, the United Provinces [Provincias Unidas del Sur] and Liga de los Pueblos Libres [League of the Free Peoples or Federal League]. Thus, the territorial representation of these political units coincide with documented historical atlases as the World Historical Atlas (Duby, 2000).

Figure 2. Map presently exhibited in the National Historical Museum of Argentina. Retrieved from https://museohistoriconacional.cultura.gob.ar/media/uploads/site-6/multimedia/tiempo_de_revolucion_infografias_descargables.pdf.

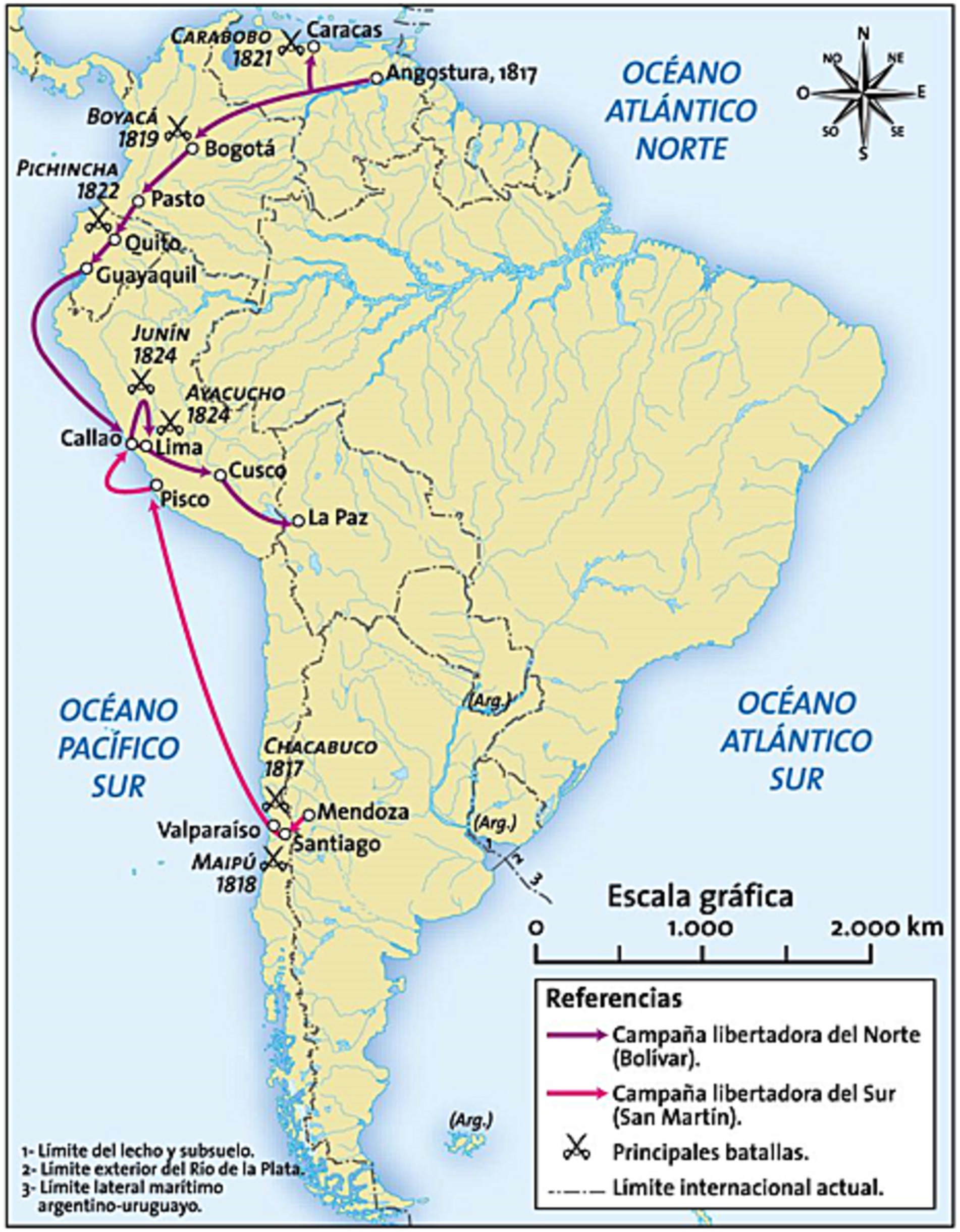

However, despite these considerations, the maps used in schools in Argentina to represent the national territory of the beginning of the 19th century and to illustrate the military campaigns for South American independence, are very different from the one we have just seen. They do not show the territorial configuration of the time. The map in Figure 3 shows the current limits of Argentina and, just as we commented above about the United States, it reproduces an essentialist image of the national territory, showing that the current frontiers were already set even before the country became independent. In other words, the map shows the current external limits of Argentina, and the rest of the countries in South America, as if they had existed by the time each of them became independent. Even when the image is trying to show historical processes that occurred before Argentina and the other countries become nation states. Thus, there is a significant difference between well-known world history atlas [i.e., for example, the atlas by Duby (2000)] and the ones used in some countries, as Argentina.

Figure 3. Map included in an Argentinian current textbook that show South America’s liberation campaigns in the early 19th century. Available in https://www.educ.ar/recursos/125203/mapas-de-america-de-temas-historicos.

Also, present and past are so mixed in the historical map that we can even read the phrase (Arg) on the Falkland Islands. This is a territory in dispute at present between Argentina and the United Kingdom, and Argentina does not have any right upon it. However, the historical map includes a reference to these islands belonging to Argentina, even when the map, as we mentioned above, represents a historical period in which Argentina did not exist yet, and so, it could not have any claim of sovereignty over that territory.

To understand where the reference to the Falkland Islands as Argentinian in a historical map comes from, it is necessary to mention that in Argentina there is a legal regulation called Ley 22,936 de la Carta [Law 22,936 of Charter]. This law establishes that the national state can forbid the commercialization and reproduction of representations of the Continental, Insular and Antarctic Territory of the Argentinian Republic that do not comply with the norm set by the National Executive Power through the National Geographic Institute. In 1941, Argentina passed Law 12,969 of Geodetic Works and Topographic Surveys. It required that maps that were published in the national territory and that totally or partially reproduced a sector of the Argentine territory had to incorporate part of the Antarctic Sector and the Falkland Islands as territories belonging to the nation state. Then, in 1983, Law 22,963 of the Charter was enacted, which modified the afore mentioned Law 12,969 and had the objectives of consolidating a national awareness of the territory and avoiding differences in geographic information about the Argentine Republic. The regulations specify that the only valid cartographic representation is the version made by the national government. At present, this law, with some minor modifications, continues to be applied in Argentina. In other words, in the maps used for school context, publishers can only reproduce the official map of the Argentine Republic by law. On the contrary, if the cartographic images do not adjust to the official cartography and are not reproduced based on the official map, which includes the Falklands as part of the territory, the publisher may be sanctioned, and the commercialization of the book may be forbidden.

5 Student’s representations about the historical national territory

The persistence of atemporal representations of the national territory may be related to the still strong presence of national contents within school history contents (Van Sledright, 2008; López, 2021). From the beginning, the territory has been present in the national master narratives about the 19th century. Sometimes, it is represented as a space that had to be liberated or recovered for the nation, from an external enemy’s threat. Wertsch (1998), for example, claims the presence of the territory to be a key element of the Russian historical master narrative that he called Triumph against alien forces. According to the author’s proposal, most of the Russian historical narratives produced by the subjects interviewed developed over four steps: (1) an initial situation in which Russians live pacifically in their territory; (2) a threat to the territory from alien forces; (3) as a consequence, there is a time of crisis and suffering for the Russian people who resist the invasion; and 4) the triumph over alien forces by the Russian people, that heroically defended their territory from the invasion. On the other hand, within the field of social psychology, Billig (1995) thinks that the territory is one of the elements over which the development of a banal nationalism is consolidated. In the same sense, Anderson (1983) considers the territory to be the place over which the members of an imagined community, independently of whether they interact daily with the place or not, experience a feeling of belonging.

These events show the importance and the presence of the territory in national historical master narratives. Moreover the representations of the space, far from being in conflict, strengthen and legitimize the master narratives (Parellada et al., 2020). Therefore, when students study national history, they are in touch with a cartographic image that reproduces the shape of the national territory. Also, the same shape is not only in school context, but it is reproduced in multiple objects as well, providing what Anderson (1983) calls logo-map. This means a simple way of drawing the shape of the nation that can be reproduced infinitely, through different objects of our everyday life, such as billboards, stamps, banknotes, regional products, and textbooks, among others. The logo-map, which is easily recognized by the citizens, becomes a national symbol of the territory. So, when we refer to a state, many times, it tends to be associated by students in particular, and people in general, to the territory represented by the logo-map and, consequently, that map becomes a symbol to the nation.

In our research, we have analyzed the concept of nation and territory. Specifically, our investigations show that very often students with no specific education in history or cartography assign the same features to the nation and to the national territory. In other words, in the research carried by our team, we found that most of the subjects interviewed in both Spain and Argentina, consider their own nation and the national territory associated to it as a fixed and immutable entity (López et al., 2015; Carretero, 2018; Carretero et al., 2018; Parellada et al., 2020).

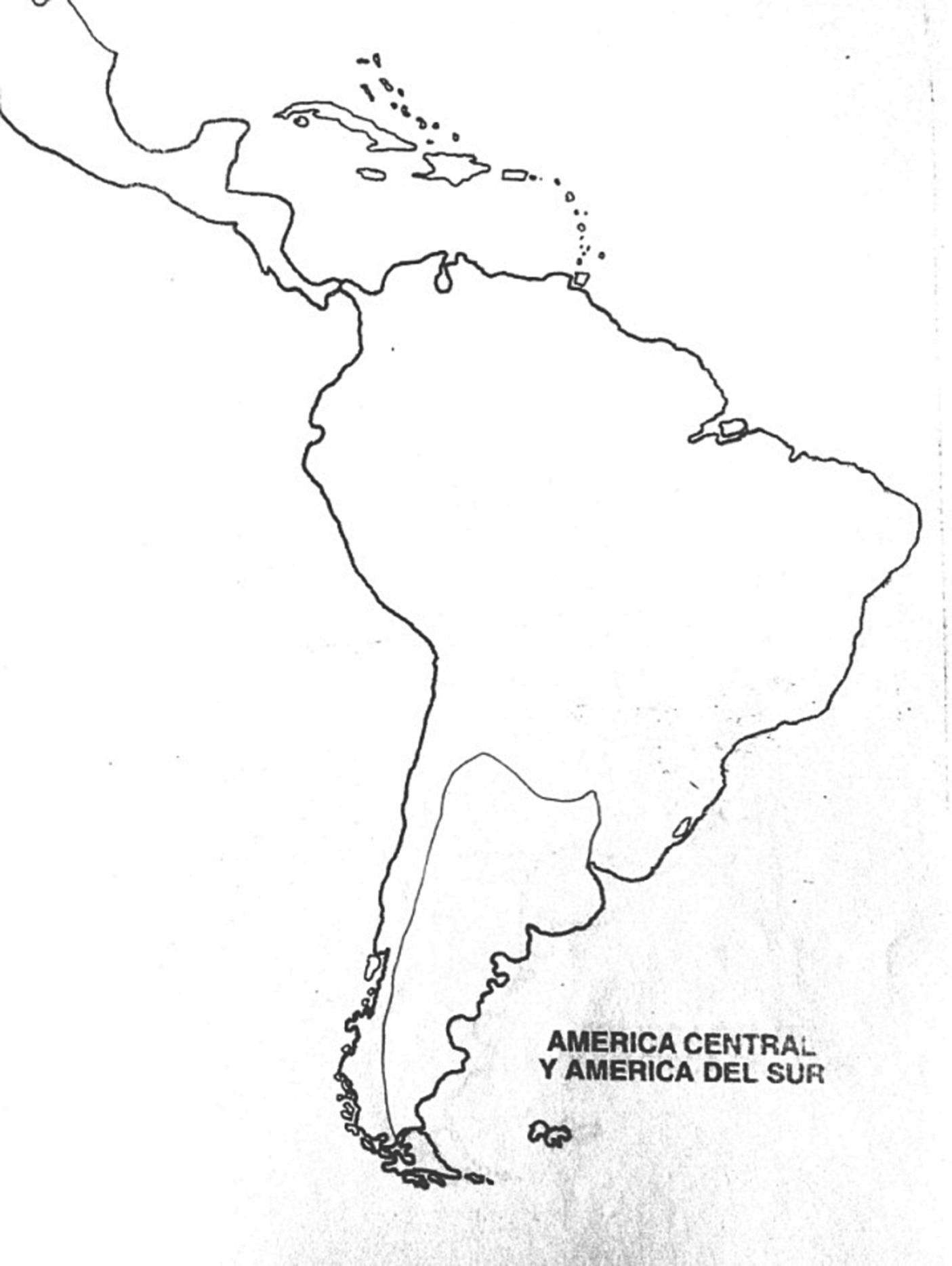

In a research of our team carried out in Argentina, we asked thirty Argentinian university students to produce a narrative about their country’s independence, on July 9th, 1816 and the transformations of the national territory caused by the Conquest of the Desert (Parellada, 2019). In such study, we asked them to produce a narrative about de independence of Argentina by drawing the borders of the territory that became independent in 1816, in a map of Latin America, all of that based on their knowledge on the topic, and then produce a narrative about the Conquest of the Desert, in order to understand if they recognized the expansion of the territory. As we mentioned above, the territory that became independent in 1816 is very different from the current one (see Figure 2). Most of the subjects interviewed draw maps very similar to Figure 4. As you can see, the map shows the current borders of Argentina, but the students were using it to refer to the territory that became independent at the beginning of the 19th century (Figure 4). Also, when students saw maps produced in the 19th century that show the Patagonia was not part of the Argentina’s territory in those years, the majority of they had not changed their considerations. Specifically, most of they considered that the cartographer was wrong because maybe “he forgot represent the Patagonia as part of Argentina” (Parellada, 2019, p. 219). In other words, for most of the students interviewed, the essentialist representation of the national territory remained unchanged even in the presence of data that contradicted it.

Figure 4. Essentialist map limits of Argentinean territory by 1816 (date of the independence) drawn by an Argentine university student in our study.

The cartographic images drawn by the students reproduce the current national borders and show some kind of atemporal space for the Argentinian territory. In other words, students seem to think that the Argentinian territory has remained unchanged for more than 200 years, instead of considering its transformations through the years as a product of a series of multicausal changes. Paradoxically, recognizing there is a continuity and the change as a consequence of historical processes is one of the abilities of historical thinking, but far from that, students tend to reproduce a model of continuity of the nation based on a nationalist approach. According to this model, the aim is to establish a continuity between past and present in national terms, so that the citizens identify themselves with certain groups from the past and they can lead their actions in the present and in the future.

Also, after drawing the maps, the students interviewed were shown different cartographic images from the end of the 19th century, where they could see the differences between the current national territory and the past one. However, even when they had information about the territorial transformations, most of the subjects interviewed did not change their initial representation and they provided arguments such as the cartographer who produced the map at the end of the 19th century forgot to include the Patagonia in the shape of Argentina (Parellada and Carretero, 2022). So, we can say there is an essentialist connection between the territory in the cartographic representations and the arguments provided, and this connection seems to outweigh the information that shows the historical transformations in the shape of the territory. We found similar results in Spain when students were asked to produce a narrative and a map about the Reconquest of Spain (López et al., 2015). This concept includes the historical period and process from the arrival of Muslim peoples to the Iberian Peninsula in 711 to their defeat in Granada in 1492 under the rule of the Catholic Monarchs. When Spanish university students were asked to draw a map about this historical process, most of them drew a map with the present borders of Spain, France, and Portugal, as if these countries had existed in the 8th century. We think that, even when more empirical work on this is necessary, it seems clear that the subjects have difficulties to understand the processes of territorial change of their own nation. So, we think it is necessary to reflect on the importance of the historical maps used in history teaching with the complexity of the historical processes related to the transformations of the national territories.

6 Final comment: thinking historically with maps

As we have tried to show in this article, considering the national territory and its transformations is an issue that has not been properly considered in school History teaching and learning yet. Historical maps show where historical processes occurred or how the territory has changed. However, as we have shown, the maps used in school textbooks and atlases usually tend to reproduce the present borders, and this produces a wrong idea that the national territory has remained as an immutable entity through the years. In this sense, we think it is important to reflect on historical maps to encourage a better understanding of the historical processes in the students and to favor the development of historical thinking. In other words, we should not only expect students to look at a map and reproduce it as it is. Instead, from a historical thinking perspective, they should be expected to consider it as a complex source they can question to understand the past better. Also, it is important to consider that in order to fully understand how both students and textbooks represent territorial changes across times it is necessary to take into account the contribution of research on geographical representations in general and studies on spatial patterns in particular. For example, Gersmehl and Gersmehl (2011), from the point of view of neuroscience, define eight features in the development of spatial thinking. No doubt these features could possibly have an influence on how human beings represent the territory of our own countries. Further research is necessary to draw clearer conclusions about this matter. But anyway, in this paper our main point is related to how cultural devices such as textbooks and other related territorial representations, very often presented by media, foster biased and essentialist views of historical maps.

As we said above, historical maps can be analyzed as sources. They were produced in a certain historical and social context and, thus, they offer information about the society that produced them. Presenting students with activities to question maps may improve the development of historical thinking. In this sense, maps as documentary sources help us understand how a society understands or understood space in a certain historical time (Harley, 1988). We can understand continuity and change not only in the way space is represented, which could be technical knowledge, but also in the way a certain society represents the space and what territories they consider important to represent and which they do not. If students learnt to ask these questions to historical maps, they could stop conceiving the territory as the shape of the present national state, and they could be able to understand that this is just one way, among many others, to map the space and to make sense of it historically. The shape of the nation state in historical maps seems to condition the subject’s historical interpretation about the territory, but we do not think that producing maps without this shape is enough. It is important to question de image and to analyze why the space is being represented in that way and how that information can be related to other historical documents.

The way in which subjects understand maps and how they interpret them is mediated by their perspectives and considerations (Jacob, 2006). Thus, school teaching centered on historical thinking should consider studying historical maps, as it could enable a different context of meaning to interpret them better than the one provided by the nation state. The use of comparison activities between different cartographic images may help students understand why some sectors of society tend to intervene legally in cartographic representations, as it is the case in Argentina, and encourage the reproduction of the current frontiers, even in periods where they did not exist. For example, they may question what territorial disputes of the present are related with this representation of space in a historical map. As students question cartographic images and compare them with others from different historical periods, or even from other societies that do not have their borders in dispute, they might be surprised, and they may even start to interrogate images with questions similar to the ones a historian would ask.

From this point of view, the purpose of working in a classroom with historical maps should not only be that students solve historical problems. They should be encouraged to take critical distance from the cartographic images and from their own conceptions about the territory in the past, trying to develop a consciousness of historicity about the territory and the different forms of representation there may be as part of a particular historic moment. Also, these activities in which students interrogate the map are a great opportunity to reflect on the narrative that builds identity, and also to reflect on some historical concepts and their evolution. All these, considered from the point of view of the different social groups coexisting in the territory and considering the conflicts between groups for power, territorial expansion, or any other conflict. The analysis of the conflict from the point of view of different groups makes it easier for the student to see multiple perspectives in the conflict and to consider arguments and counterarguments about it.

In other words, working historically with maps and questioning them may challenge national historical narratives and the understanding of the national territory when they are in tension with some official historical explanations. Seeing cartographic representations as constructions and analyzing them as historical sources may contribute to change how our conception of the territory affects our perception and our relationship with it, its borders and with others, that we consider foreigners. Students need tools to develop their historical thinking, but these are not general abilities. It is also necessary to reflect on historical maps specifically to question them and to challenge the hegemonic historical master narrative.

Author contributions

CP: Investigation, Writing – original draft. MR-M: Conceptualization, Supervision, Writing – original draft. MC: Conceptualization, Writing – original draft.

Funding

The author(s) declare financial support was received for the research, authorship, and/or publication of this article. The authors declare having received the following financial support for the research, authorship and/or publication of this article: This work was financed by the project PID2021-127529OB-I00 (AEI-MCIN FEDER), Spain, to which the second and third authors belong and PICT 2020-SERIEA-02828 (ANPCYT, Argentina), to which the first and third author belong, both coordinated by the third author.

Conflict of interest

The authors declare that the research was conducted in the absence of any commercial or financial relationships that could be construed as a potential conflict of interest.

The reviewer AV declared a shared affiliation with the authors MC and MR-M at the time of review.

Publisher’s note

All claims expressed in this article are solely those of the authors and do not necessarily represent those of their affiliated organizations, or those of the publisher, the editors and the reviewers. Any product that may be evaluated in this article, or claim that may be made by its manufacturer, is not guaranteed or endorsed by the publisher.

Footnotes

1. ^The Arizona Border Recon is a group of more than 200 former by Americans military men patrolling and checking on the limits between the United States and Mexico in Ariyaca, Arizona State.

References

Agnew, J. (2008). Borders on the mind: re-framing border thinking. Ethics Glob. Polit. 1, 175–191. doi: 10.3402/egp.v1i4.1892

Alridge, D. P. (2006). The limits of master narratives in history textbooks: an analysis of representations of Martin Luther king. Jr. Teachers College Record 108, 662–686. doi: 10.1111/j.1467-9620.2006.00664.x

Anderson, B. (1983). Imagined communities: Reflections on the origin and spread of nationalism. London, UK: Verso.

Aparicio Frutos, J. J., and Rodríguez-Moneo, M. (2015). El aprendizaje humano y la memoria. Una visión integrada y su correlato neurofisiológico [human learning and memory. An integrated view and its neurophysiological correlate.]. Madrid, Spain: Pirámide.

Bednarz, S. W. (2016). The practices of geography. Geogr. Teach. 13, 46–51. doi: 10.1080/19338341.2016.1170712

Bednarz, S. W., Acheson, G., and Bednarz, R. S. (2006). Maps and map learning in social studies. Soc. Educ. 70:398-404, 432.

Berger, S. (2012). “De-nationalizing history teaching and nationalizing it differently! Some reflections on how to defuse the negative potential of national (ist) history teaching” in History education and the construction of national identities. eds. M. Carretero, M. Asensio, and M. Rodríguez-Moneo (Charlotte, NC: Information Age Publishing).

Caquard, S. (2013). Cartography I: mapping narrative cartography. Prog. Hum. Geogr. 37, 135–144. doi: 10.1177/0309132511423796

Carretero, M. (2011). Constructing patriotism. Teaching history and memories in global worlds. Charlotte, NC: Information Age Publishing.

Carretero, M. (2018). “Historical consciousness and representations of National Territories. What the trump and Berlin walls have in common” in Contemplating historical consciousness: Notes from the field. eds. A. Clark and C. Peck (Cham, Switzerland: Berghahn Books).

Carretero, M., Pérez-Manjarrez, E., and Rodríguez-Moneo, M. (2022). “‘Reenacting the past in the school yard’. Its role in history and civic education” in Historical reenactments. New ways of experiencing history. eds. M. Carretero, B. Wagoner, and E. Pérez-Manjarrez (New York, US: Berghahn Books).

Carretero, M., van Alphen, F., and Parellada, C. (2018). “National Identities in the making and alternative pathways of history education” in The Cambridge handbook of sociocultural psychology. eds. A. Rosa and J. Valsiner. 2nd Edn (Cambridge, UK: Cambridge University Press).

Craib, R. (2002). A nationalist metaphysics: state fixations, National Maps, and the geo-historical imagination in nineteenth-century México. Hisp. Am. Hist. Rev. 82, 33–68. doi: 10.1215/00182168-82-1-33

Culcasi, K. (2011). Cartographies of supranationalism: creating and silencing territories in the “Arab homeland”. Polit. Geogr. 30, 417–428. doi: 10.1016/j.polgeo.2011.08.003

Dym, J., and Offen, K (2011). Mapping Latin America Cartographic Reader. Chicago. The University of Chicago Press.

Epstein, T., and Salinas, C. (2018). “Research methodologies in history education” in The Wiley International handbook of history, teaching and learning. eds. S. Metzger and L. McArthur Harris (London, UK: Wiley-Blackwell).

Gersmehl, P. J., and Gersmehl, C. A. (2011). Spatial thinking: where pedagogy meets neuroscience. Prob. Educ. 27, 48–66.

Harley, J. B. (1988). Silences and secrecy: the hidden agenda of cartography in early modern Europe, Imago Mundi. Int. J. Hist. Cartogr. 40, 57–76. doi: 10.1080/03085698808592639

Herb, G. (2004). Double vision: territorial strategies in the construction of National Identities in Germany, 1949-1979. Ann. Assoc. Am. Geogr. 94, 140–164. doi: 10.1111/j.1467-8306.2004.09401008.x

Jacob, C. (2006). The sovereign map. Theoretical approaches in cartography throughout history. Chicago, US: The University of Chicago Press.

Kamusella, T. (2010). School history atlases as instruments of nation-state making and maintenance: a remark on the invisibility of ideology in popular education. J. Educ. Media Mem. Soc. 2, 113–138. doi: 10.3167/jemms.2010.020107

LeBlanc, M. (2016). American revolution maps in the classroom: K-12 education at the Norman B. Leventhal map centre. J. Map Geogr. Librar. 12, 281–294. doi: 10.1080/15420353.2016.1209611

Lee, P. (2005). “Putting principles into practice: understanding history” in Committee on how people learn (Eds.). How students learn: History, mathematics and sciences in the classroom (Washington, US: National Academies Press).

Lévesque, S. (2011). “What it means to think historically” in New possibilities for the past: Shaping history education in Canada. ed. P. Clark (Vancouver, Canada: UBC Press).

Lois, C. (2014). Mapas Para la Nación: Episodios en la Historia de la Cartografía Argentina [maps for the nation: episodes in the history of argentine cartography]. Biblos.

López, C. (2021). Las narrativas nacionales en la mente de los estudiantes: Principales características y pautas para el desarrollo del pensamiento histórico [National narratives in students’ mind: Main features and guidelines for developing historical thinking]. Campo Abierto 40, 293–306. doi: 10.17398/0213-9529.40.3.293

López, C., Carretero, M., and Rodríguez-Moneo, M. (2015). Conquest or reconquest? Students’ conceptions of nation embedded in a historical narrative. J. Learn. Sci. 24, 252–285. doi: 10.1080/10508406.2014.919863

McLean, K. C., and Syed, M. (2015). Personal, master, and alternative narratives: an integrative framework for understanding identity development in context. Hum. Dev. 58, 318–349. doi: 10.1159/000445817

Orrego Luco, L. (1902). Los problemas internacionales de Chile. La cuestión Argentina, el tratado de 1881 y negociaciones posteriores [the international problems of Chile. The argentine question, the 1881 treaty and subsequent negotiations]. Imprenta, encuadernación y litografía Esmeralda.

Parellada, C. (2019). Representaciones del territorio nacional y narrativas históricas. Implicaciones Para la enseñanza de la historia [representations about national territory and historical narratives. Implications for the history teaching] Doctoral Thesis, National University of La Plata. Available at: http://sedici.unlp.edu.ar/handle/10915/80106

Parellada, C., and Carretero, M. (2022). “Digital historical maps in classrooms. Challenges in history education” in History education in the digital age. eds. M. Carretero, M. Cantabrana, and C. Parellada (Cham: Springer).

Parellada, C., Carretero, M., and Rodríguez-Moneo, M. (2020). Historical borders and maps as symbolic supporters of master narratives. Theory Psychol. 31, 763–779. doi: 10.1177/0959354320962220

Peck, C., and Seixas, P. (2008). Benchmarks of historical thinking: first steps. Can. J. Educ. 31, 1015–1038.

Pérez-Manjarrez, E., and Carretero, M. (2021). “Historical maps as narratives: anchoring the nation in history textbooks” in Analysing historical narratives. On academic, popular and educational framings of the past. eds. S. Berger, N. Launch, and C. Lorenz (New York, US: Berghahn Books).

Rodríguez-Moneo, M., and López, C. (2017). “Concept acquisition and conceptual change in history” in Palgrave handbook of research in historical culture and education. eds. M. Carretero, S. Berger, and M. Grever (London, UK: Palgrave Macmillan).

Seixas, P. (2017). A model of historical thinking. Educ. Philos. Theory 49, 593–605. doi: 10.1080/00131857.2015.1101363

Seixas, P., and Morton, T. (2013). The big six historical thinking concepts. Toronto, Canada: Nelson Education.

Thorp, R., and Persson, A. (2020). On historical thinking and the history educational challenge. Educ. Philos. Theory 52, 891–901. doi: 10.1080/00131857.2020.1712550

Van Boxtel, C., and van Drie, J. (2018). “Historical reasoning: conceptualizations and educational applications” in The Wiley International handbook of history teaching and learning. eds. S. Metzger and L. Harris (London, UK: Wiley).

Van Sledright, B. (2008). Narratives of nation-state, historical knowledge, and school history. Rev. Res. Educ. 32, 109–146. doi: 10.3102/0091732X07311065

Wertsch, J. (2018). “National Memory and where to find it” in Handbook of culture and memory. ed. B. Wagoner (New York, US: University Press).

Wertsch, J. V. (2021). How the nations remember a narrative approach. Oxford: Oxford University Press.

Wineburg, S. (2001). Historical thinking and other unnatural acts. Philadelphia, US: Temple University Press.

Keywords: historical maps, historical thinking, historical consciousness, history education, historical maps of Spain, historical maps of Argentina

Citation: Parellada C, Rodríguez-Moneo M and Carretero M (2024) Historical maps as a neglected issue in history education. Students and textbooks representations of territorial changes of Spain and Argentina. Front. Educ. 8:1287500. doi: 10.3389/feduc.2023.1287500

Edited by:

Delfín Ortega-Sánchez, University of Burgos, SpainReviewed by:

Alfonso Garcia De La Vega, Autonomous University of Madrid, SpainPilar Rivero, University of Zaragoza, Spain

Pedro Miralles-Martínez, University of Murcia, Spain

Copyright © 2024 Parellada, Rodríguez-Moneo and Carretero. This is an open-access article distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution License (CC BY). The use, distribution or reproduction in other forums is permitted, provided the original author(s) and the copyright owner(s) are credited and that the original publication in this journal is cited, in accordance with accepted academic practice. No use, distribution or reproduction is permitted which does not comply with these terms.

*Correspondence: Cristian Parellada, cristianparellada@hotmail.com

Cristian Parellada

Cristian Parellada María Rodríguez-Moneo

María Rodríguez-Moneo Mario Carretero

Mario Carretero