“I’ma put the lil homies on next”: mixtape methodology and mapping Black men’s college experiences

- Wake Forest University, Winston-Salem, NC, United States

In recent years, many studies have attempted to explore the experiences of historically marginalized populations within higher education; especially Black men. While most studies expand the discourse about the Black male experience in higher education, few incorporate arts-based methodologies that uniquely speak to the cultural sensibilities of Black men. This study remixes traditional qualitative methodologies through an arts-informed, hip-hop pedagogical perspective by inviting participants to write and record original music in response to a prompt related to an original research question: What does the creation of a Hip-Hop mixtape by Black, male, college-educated emcees, reveal about Black men’s experiences in higher education? Together, this curated collection of songs formed a mixtape, which was made available across multiple streaming platforms, and introducing the counternarratives of Black male hip-hop collegians to audiences beyond the academy. The resulting mixtape offers practical implications for revolutionizing the way educators’ may center cultural knowledge as means of collecting data that captures the nuance of marginalized students’ experiences within (and beyond) the context of school.

Introduction

In August of 2023, hip-hop culture – that is, a multimodal mode of cultural expression, consisting of DJing, emceeing, breakdancing, and graffiti – turns 50 years old. This big bang, this world building cultural phenomena was made possible by the ingenuity of Black and Brown youth, whose sense of joy and wonder would emanate, far beyond the social, economic, and political upheaval that categorized life in the South Bronx. As the civil rights movement came to a close and the children of that movement came of age in the early 1970s, there was a need to create something that was uniquely them – it wasn’t jazz or gospel, disco or rhythm and blues. Instead, it was an amalgam of all of these aesthetics – it was sonic and visual, embodied and lyrical. When DJ Kool Herc packed the rec room at 1520 Sedgwick Ave., and used two turntables to isolate and prolong break beats on popular records, he not only suspended bodies in motion, sustaining the party’s good vibes, he – and other innovative DJs of this era – gave us an auditory canvas to paint our stories. This technique of extended breaking was something Herc learned from his native Jamaica, where the DJ judged by simple equation: the bigger the sound system, the bigger the party. Since Herc laid claim to the loudest sound system in his neighborhood, few would have envisioned the sonic boom that was to come. Though hip-hop would soon become the globalized, mainstream artform we know today, perhaps what was always understood by those who create it and connect with it, the genius of hip-hop culture – and all of its expressive elements – could not be contained in the walls of that rec room.

For half of a century, the Black and Brown youth responsible for laying the foundation of hip-hop culture, were purveyors of radical joy, truth-tellers, and world-builders. For this reason, it is important that educators and researchers alike, find new ways to embody the innovative spirit of hip-hop culture by attempting to understand its utility in different spaces, amplifying Black and Brown voices along the way.

Thankfully, the past 25 years have featured groundbreaking research in the realm of culturally-relevant (Ladson-Billings, 1995), −responsive (Tierney, 1999), −sustaining (Paris, 2012), and-revitalizing (McCarty and Lee, 2014) pedagogies rooted in the preexisting knowledges of Communities of Color, which have been historically marginalized both within and beyond the context of school. Such is the reason why recent pedagogical innovations, as it relates to cultural phenomena like Hip-Hop and spoken word poetry, continue to push the bounds of what culture can do in educational spaces. This, coupled with a newfound interest in Black men’s experiences in colleges and universities, create a critical moment in educational scholarship for the sustained exploration of how minoritized ways of knowing can inform student success and institutional change.

I enter this project as an education non-profit professional, former college administrator, professor, scholar, poet, and emcee; but more than that, I am a husband, father, and Hip-Hop head with a firm belief that music is not just a window to the soul. It is a gateway to healing. In my lowest, most morally and academically challenging moments as a college student, Hip-Hop and spoken word poetry provided an avenue for introspect, meaning making, and perhaps most importantly, community building. When I wrestled with imposter syndrome and questioned my sense of belonging, there was a steady stream of beats, rhymes, mics, packed crowds, big stages, and bright lights to silence my discontent. To that end, I believe we, as scholars and practitioners in higher education, are at a critical juncture. Between the rapid racial and ethnic diversification of American schools, persistent disparities in educational outcomes, and a rampant global health crisis, the academy, much like our K-12 colleagues, must learn to pursue meaning and create new knowledge through culturally innovative means. Now, perhaps more than ever, it is incumbent upon us to design emancipatory research that venerates cultural knowledge rooted in our subjects’ ways of being. Doing so begins the long process of repairing the breach between the academy and the communities we aspire to liberate through scholarship.

In this article, I will expound on a unique qualitative, arts-informed research methodology known as mixtaping or mixtape methodology (Livingston, 2023) – which inlists the voices of Hip-Hop artists to write and record songs in response to a prompt related to a particular phenomena. The resulting mixtape itself, is data; a key finding to be shared broadly across multiple music streaming platforms. Rather than solely publishing and presenting these findings in niche, expensive, jargon-intensive academic journals and conferences, the mixtape is readily accessible to the public. In this case, I use mixtape methodology to explore Black men’s experiences and meaning-making processes in college, while offering important considerations for other higher education professionals and stakeholders.

Literature review

As the focus on Black men in academic journals, conference presentations, and dissertations continues to rise, so too has the range of projects dedicated to Black men’s experiences in higher education. Dancy and Brown (2012) explore the ways in which “education may participate in the process of reconstructing racial and other identities for African American males and how this process is directly tied to addressing disparate outcomes among this group in education,” (p. x). Harper and Wood (2016) expound on this work in their edited volume dedicated to Black male student success across the educational pipeline, from preschool to Ph.D. To that end, scholars have continued to advance research on Black males in higher education through anti-deficit (Harper, 2013) and resilience frameworks (King and Palmer, 2014), that illustrate the cultural assets Black men activate in order to successfully navigate colleges and universities.

More recent studies have reflected on the ways in which Black males approach the postsecondary planning and enrollment process (Rhoden, 2018; Hines et al., 2020, 2023), once again, through asset-based frameworks as articulated in Harper (2012) famed national report on Black male achievement at colleges and universities. In addition to this work centering Black male experiences and voice on college campuses, scholars have continued to put the pressure on universities – especially predominantly white institutions (PWIs) – to make good their promise to diversity and inclusion by adapting new theoretical frameworks like empathetic transcendence, an action that Bridgeforth (2018) says, “requires campus leaders [to] crate an interconnected system of programs, events, and opportunities for administrators, faculty, staff, and students to learn, understand, and appreciate, the historical context of what it means for someone to be African American and male in a predominantly white society,” (p. 451). In the case of Black male’s experiences and identity development at Historically Black Colleges and Universities, Rogers and Mitchell (2022) indicate that identity development occurs in four stages: (1) acknowledgment of Black male identity, (2) understanding of differences among Black males, (3) creation of professional identity, and (4) transition into Black male role model. While Rogers & Mitchell acknowledge that the HBCU context is unique, and these results do not necessarily apply to Black males at PWIs, their work carries on the tradition of exploring the efficacy of culturally competent campus leadership, and the role they play reducing harm and invisibility (Allen, 2020) caused by institutional racism, which, at times, according to Green (2016), the university often exacerbates.

These frameworks were vital to the establishment of methodological and theoretical foundations for understanding the Black male experience in education, more broadly. The early 2000s saw an increase in qualitative scholarship in higher education institutional assessment (Harper and Museus, 2007). Since that time, scholars like McLean et al. (2018) continue to insist that cultural context matters in qualitative research; especially inquiry aimed at student identity development. To that end, scholars have made great strides in introducing innovative qualitative methods that speak to Black men’s cultural capital. Building on the framework of Critical Race Theory (CRT), and its tenet of counter narrative storytelling, Harper (2009), designed a set of composite stories based on face-to-face interviews with 143 Black male undergraduates, intended to oppose dominant discourse concerning the social and educational status of Black men in America. Other phenomenological studies about Black men in higher education featured face-to-face and telephone interviews. Most notably is that of Harper and Quaye (2007), whose work revealed that Black male student leaders at PWIs develop cross-cultural communication skills, care for other disenfranchised groups, and pursue social justice via leadership and student organization membership. Similarly, Brooms (2019) multisite qualitative study exploring the narratives of Black male college students’ engagement experiences in a Black Male Initiative (BMI) program across three different campuses, featured a combination of participant observations, interviews, and discourse analysis from program data and printed materials. This robust repository of data revealed that students identified bonding with their Black male peers and learning from Black men connected to the program as central components of the BMI community (Brooms, 2019).

While this brief snapshot reflects a myriad of qualitative approaches to inquiry centering Black men in college, there are fewer studies that employ arts-based methodologies. McGowan (2017) used a visual methodology to explore how African American college men conceptualized gender within their interpersonal relationships at a traditionally White institution. While McGowan (2017) still relied on semi-structured interviews, his methods also included photo elicitation with the 17 participants who shared stories about their interpersonal relationships with other men, and ascribed multiple meanings to images that yielded key insights into how they developed and maintained peer connections on campus. According to Tonge et al. (2015), photo elicitation is “a qualitative technique where participants are asked to take photographs relating to the concept under study, and these are then used as triggers for underlying memories and feelings during a subsequent interview,” (p. 741). Participants within this methodology produced data in new ways that pushed the boundaries of traditional qualitative research, adding a richness that could only be captured through their unique lens. In a later study, McGowan (2018) explored Black college men’s experiences participating in a research study that explored sensitive topics, which also involved their identity and interpersonal relationships. In it, McGowan (2018) once again, uses photo elicitation alongside semi-structured interviews to identify five important themes that reflect Black men’s meaning-making processes when participating in research studies that invite vulnerability: (a) experiencing catharsis despite uncomfortable moments, (b) unpacking unresolved issues from childhood, (c) exploring the nature of friendships, (d) fostering self-awareness and growth, and (e) being invested in the study’s aims and outcomes. It would seem then, that finding creative, perhaps even arts-informed, mechanisms for Black college men to share their stories continues to produce meaningful experiences for participants and researchers alike. Other arts-informed higher education research, though not unique to Black men, included Loads (2009), who invited university lecturers to create collages, masks, and small-scale sculptures in response to the prompt, “what does teaching mean to me?.” Similarly, Jones (2010) used poetic transcription – that is, reproducing interview transcripts in distilled form, paying attention to the emphasis, rhythm and nuance of speech – to investigate faculty teaching practices. Gitonga and Delport (2015) built on this tradition, by designing participatory research with arts-based data-generation; which included, drawing and lyric inquiry, and the use of Hip-Hop music. Their study found that Hip-Hop music prompted profound engagement with the self, providing participants with a space to, “reflect on and articulate the continual, interactional and situational dimensions of their lives” (p. 990–991). Ultimately, Gitonga and Delport (2015) lay the framework for establishing Hip-Hop as a transformative tool for data-generation in participatory research projects with students (age 18–22) who identify with the culture. Levy et al. (2022) go a step further in implementing a culturally responsive, evidence-based hip-hop and lyrical intervention – centering the meaning-making habits of Black and Brown youth – in an attempt to help counselors better support students’ social emotional development. Together, these methodological innovations provide the necessary groundwork for more creative scholarly endeavors that elevate the cultural sensibilities of students of color. Although scholars admit there is much to be learned about arts-based methodologies, many believe there is value in finding alternative ways of representing their ideas and experiences (Burge et al., 2016).

Methodology

Theoretical framework

This project is grounded in two theoretical frameworks that not only center participant voice, but also decolonize the research process: Critical Race Theory and community cultural wealth. The former, Critical Race Theory, centers the Outsider, as Yosso puts it, “transgressive knowledges,” that undermine the notion that students of color enter academic spaces with “cultural deficiencies,” (p. 70). It is important to recognize, too, that CRT has received criticism in recent years by conservative pundits who have obfuscated its meaning, stripped away its academic rigor, reducing it to the status of landmine on the battlefield of cultural warfare. Rather than watch my step, I choose to walk confidently in the direction of CRT, as its roots in legal studies, ethnic studies, women’s studies, history, and sociology provide a viable landscape, upon which to explore the experiences of historically marginalized groups in majority contexts (Solórzano and Yosso, 2001; Crenshaw, 2002). Solórzano (1997, 1998) work, which explores CRT within the context of education is grounded in five core tenets: (1) the intercentricity of race and racism; (2) the challenge to dominant ideology; (3) the commitment to social justice; (4) the centrality of experiential knowledge; and (5) the utilization of interdisciplinary approaches. Among these tenets, perhaps the most relevant to this study are challenging dominant ideologies which are, in this case, research methods that are not sensitive to Black men’s ways of knowing; and the centrality of experiential knowledge, which is evidenced by the implementation of an arts-informed research method, that centers participant’s utilization of original hip-hop lyricism.

With regard to community cultural wealth, Yosso (2005) established this framework to challenge traditional, Bourdieuian conceptualizations of cultural capital. In her framework, Yosso (2005) states, “community cultural wealth is an array of knowledge, skills, abilities and contacts possessed and utilized by Communities of Color to survive and resist macro and micro-forms of oppression,” (p. 77). The framework itself, which is also grounded in CRT, insists that community cultural wealth is nurtured by six forms of capital: aspirational, navigational, social, linguistic, familial, and resistant capital. Each of which, according to Yosso, “build on one another,” constructing a new understanding of whose culture has value in majoritarian society. When enacted, these six forms of capital provide a pathway to survival and wholeness for marginalized groups when navigating institutions and systems that were not designed for them to thrive. While it is unclear which forms of capital within the community cultural wealth framework will be most salient within the data, it is abundantly clear that hip-hop lyricism and mixtape-making more broadly, provides an opportunity for limitless discovery and self-actualization.

The study

Given the scholarly innovations of the past decade, especially those related to Hip-Hop educational research (Petchauer, 2017), the field is poised to take yet another giant leap forward. With the continued interest in Black men’s experiences in higher education, it seemed appropriate to attempt a new, alternative methodological approach to a question of timeless significance, carried out in the spirit of the #HipHopEd movement. After all, Emdin et al. (2018) remind us that #HipHopEd, “is aimed at disrupting the oppressive structures of schools and schooling for marginalized youth through a reframing of hip-hop in the public sphere,” (p. 1). Therefore, like Livingston (2023), I propose a new qualitative, arts-based research method, called mixtaping, that, not only elucidates cultural knowledge within an under-studied population in postsecondary education – Hip-Hop artists – but also situates their knowledge within the public sphere. Petchauer (2007) refers to these students as Hip-Hop collegians – college students whose educational interests, motivations, and practices have been shaped by involvement in Hip-Hop. Livingston (2023) stipulates that mixtape methodology is grounded by five distinct steps: (1) Identify study participants that are actively engaged in creating hip-hop music; (2) Foreground participant interviews within the research design; (3) Ask participants to respond to a prompt by writing and recording an original song; (4) Determine a frame for analysis – which in this instance, would by lyrical inquiry (Leggo, 2008); and (5) Share across multiple streaming platforms.

With this in mind, highlighting the experiences of Black men in college, who also identify as Hip-Hop artists or Hip-Hop collegians, may provide fresh perspective on how we, as educators, can best serve the social, emotional, and academic needs of this historically marginalized community within the landscape of higher education. Therefore, this qualitative, arts-informed study was grounded by the question:

What does the creation of a Hip-Hop mixtape by Black, male, college-educated emcees, reveal about Black men’s experiences in higher education?

In lieu of the expansiveness, accessibility, global appeal of Hip-Hop music, it seemed that compiling an original mixtape centering the college experiences of Black men allowed for a unique sort of counter narrative storytelling.

To respond to this inquiry, it was important that I design a research method that would honor the meaning making processes that Hip-Hop music, production, and performance provides. The study – and thus, the mixtaping method – opened with hour-long, one-on-one participant interviews, with questions exploring three key themes: (1) Hip-Hop background and origin story; (2) Creating Hip-Hop in college; and (3) Being Black and male at the institution. In many ways, these interviews were as much about information-gathering as they were about establishing trust. The interviews, which took place over Zoom, were vital to the process of building rapport, in preparation for the subsequent stages of the research design.

Next, at the conclusion of the interview, participants were given a prompt, to which they were required to write and record one song. The prompt – Describe your experience as a Black man at your institution – was posited more as a destination rather than a directive. In other words, although the participants were instructed toward this thematic end point, how they arrived at that destination was completely up to them. What I hoped to transpire was a compilation of songs that was lyrically, sonically, and aesthetically diverse. Because Black men’s experiences are varied and intersectional across time, place, and institutional type, it was important to create a prompt that allowed for the meaningful exploration of those subtleties. The song lyrics were analyzed through a lyric inquiry framework, which according to Nielsen (2008) refers to both the research activity and its outcome, namely the lyrics, in other words a short poem of songlike quality that is generated. This method thus marries the concept of lyric with that of research (p. 95). All the materials – including interview audio files and transcripts, song lyrics and song files – were saved in a google drive folder and shared with each participant in the study for their review.

Finally, after analyzing the qualitative data (e.g., interviews, song transcripts, and MP3 song files), I arranged and released the songs on a mixtape, entitled KEYS: Knowledge Essential for Your Success. The mixtape was uploaded to UnitedMasters – an independent digital music distribution service – and made available across multiple streaming platforms, including Apple Music, Spotify, and Tidal. Through UnitedMasters, I was able to add album cover art, credit the participants using their chosen rap aliases, and track the number of streams each song received. While the number of streams does not reveal much about how audiences are consuming, engaging with, and actively interpreting the content of the mixtape, it does demonstrate how Hip-Hop exists as a form of entertainment and public pedagogy (Williams, 2009). In the true spirit of Hip-Hop, mixtaping is a methodological approach, designed to erode the culture of elitism that characterizes scholarship in the academy.

Participants

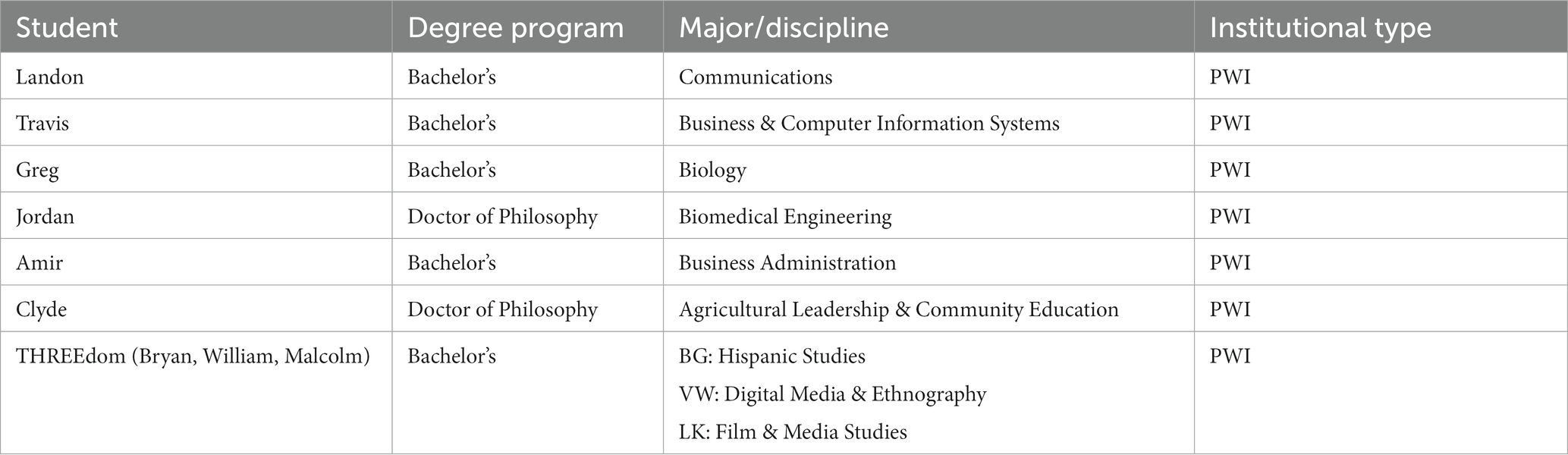

Participants for this study were recruited through various means. After receiving IRB approval, I shared information about the study across multiple social media platforms, including Facebook, Instagram, LinkedIn, and Twitter. I also sent emails to fellow #HipHopEd researchers and colleagues at other institutions who worked closely with undergraduate musicians and were connected to the Hip-Hop scene across their respective campuses. After receiving a few leads, I followed up with the prospective participants via Direct Message and email, providing further detail about the study, its requirements, and gauging their continued interests. Upon receiving favorable responses, I scheduled and conducted six interviews with nine participants, and received five songs, which were included in the mixtape, chronicling the experiences of Black men in higher education. Table 1 lists the participants in the study; each of whom have been given pseudonyms to protect their identities.

Although all the participants identify as cisgender, heterosexual Black men at PWIs, they bring with them a diversity of experience in higher education. Landon and Amir both took time away from undergraduate coursework; Landon later re-enrolled at his university after an extended absence due to mounting family responsibilities, while Amir transferred to a new university, after dropping out of his original institution and joining the Marine Corps. Prior to enrolling at PWIs, Amir and Clyde both attended HBCUs. Amir and Clyde, within the past 4 years, have also become fathers; an identity they both regard as motivation for their academic success. Bryan, a member of the trio THREEdom, after completing his undergraduate degree in Hispanic Studies, is currently enrolled in biology courses in a post-baccalaureate program, completing prerequisites for graduate school. Similarly, William is enrolled at a local community college, completing a sustainable small farm technician certificate program. All the while, each of these men are learning amid a global health crisis that has, in many ways, upended their respective experiences in postsecondary education.

Findings

Results & analysis

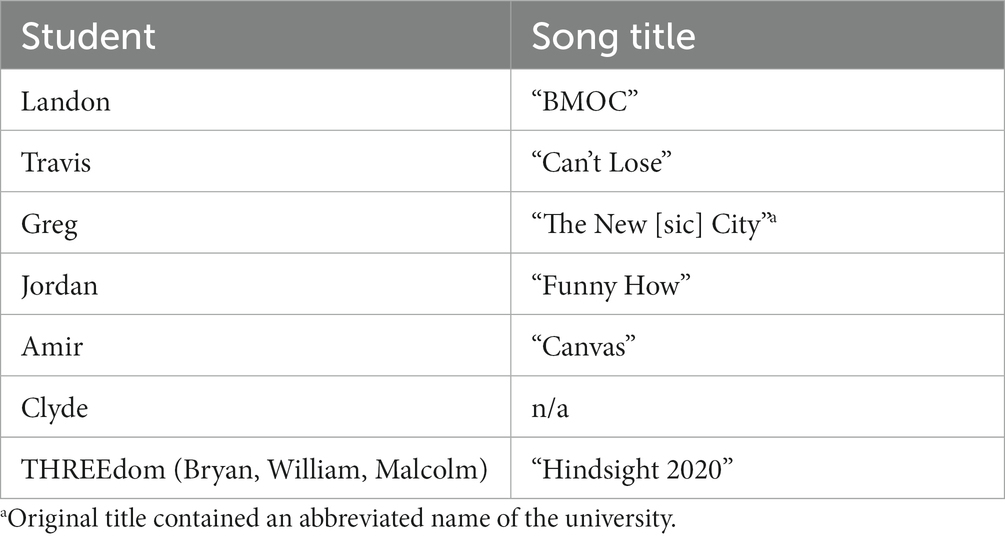

Of the nine (9) participants interviewed for this study, eight (8) submitted recorded work. THREEdom, of course, submitted one (1) song featuring its three (3) members, while five (5) other participants – Landon, Travis, Greg, Jordan, and Amir – offered a contribution to the mixtape. Clyde was the only participant that did not submit a song. Admittedly, I was worried that the pandemic and limited access to recording technology would hamper participants’ ability to record new music. Initially, I was surprised that so many participants offered their voices to this endeavor. When I thought about Hip-Hop Culture, its foundation and functionality, however, I realized that Hip-Hop has always been a sort of creative declaration in the face of adversity; a means of making a way out of no way; finding joy in moments of peril. Based on our conversations, it is plausible that the participants would’ve found a mechanism for writing, recording, and sharing their music regardless of this study. As William of THREEdom notes in one of his verses:

“God got us, there’s no stopping

This is not a hobby

We live and breathe this music

That’s what got us out the lobby.”

The act of creating Hip-Hop is, for many of the participants, a source of healing and community building, a revival of the soul (Adjapong and Levy, 2021; Levy, 2021). Sharing the music with their audiences, seemed to imbue each participant with a sense of affirmation; a sentiment with profound social, emotional, and academic implications in the participants’ experiences at their respective institutions. The conversations and mixtape song submissions yielded three distinct themes related to the original research question, revealing that these nine, college-educated, Black male emcees: (a) regard their institutions as the “new trap”; and (b) define themselves in relation to a ubiquitous “they”; and use their lyricism to pay it forward, or “put you on game.” Table 2 lists the titles of each of the participants’ songs.

Navigating the new trap

Upon first listen to the mixtape, it is easy to get lost in the barrage of similes, metaphors, melodies, hooks, and stellar instrumentation. For all that the mixtape has to offer, perhaps its most powerful element is the participants’ storytelling. Each of them offers a unique insight into how they navigate their respective institutions. This concept is reminiscent of Yosso (2005) concept of community and cultural wealth, that is, “an array of knowledge, skills, abilities, and contacts possessed and utilized by Communities of Color to survive and resist macro and micro-forms of oppression,” (p. 77). In her model of community and cultural wealth, Yosso (2005) refers to navigational capital as the skills of maneuvering through social institutions; more specifically, those institutions that were designed without Communities of Color in mind. To that point, Greg raps:

“I heard it through the grapevine this wasn’t my America

It wasn’t meant for us, but I’ma make sure to embarrass her.”

Such a declaration is a reminder that Greg’s presence at his university, much like other social institutions grounded in whiteness, is often questioned and contested. Thus, he wields lyricism as a means of illuminating historical atrocities against Black and Brown bodies that America – which is, in this sense, a macrocosm of his university – might regard as particularly embarrassing. For the participants, Hip-Hop music provides an important avenue for meaning making, in addition to self-expression. The act of creating Hip-Hop music, more specifically, compels these Black men to reflect, process, and communicate their navigational strategies – or survival tactics – as they pursue their respective degrees, in spaces that were not historically intended to serve them.

The participants’ understanding of their survival was not borne of their university experience. Several participants liken their time at their colleges to a popular subgenre of Hip-Hop music, called trap. Scholars contend that the trap rappers’ music – like Jeezy, Gucci Mane, and Future – which usually features heavy 808 kick drums and melodic synths, cannot be disaggregated from the practice of production in which it originally appears (Kaluža, 2018). According to Adaso (2017), the trap signifies a place where drugs and other illegal businesses take place and a certain lifestyle is practiced. As Kaluža (2018) notes, “the term trap is appropriate because it is hard to escape from a certain lifestyle in which people are entrapped,” (p. 25). To that end, Amir raps:

“I ain’t get no sleep

But Jeezy told me ‘trap or die’

So I cannot close my eyes.”

This connection between the trap and higher education is an important one. Amir’s conceptualization of the trap is both material and metaphorical. In this instance, the term trap in its verb tense, compels Amir to participate in a system that’s profiting from his demise. For this reason, even Travis’ song title, “Cannot Lose,” which he later reiterates in his ad-libs, takes on additional meaning. It is an acknowledgement that higher education is, for Black men – and other underrepresented populations – as much a risk as it is an opportunity; an opportunity the participants seized with a vengeance. For instance, Greg asserts:

“I’m serving up the beat, no MSG

The system tried to tie me down

I turned the trap in two degrees.”

Together, Greg and Amir’s songs begin to lay a framework for understanding what the trap is (e.g., the industry of higher education) and how to effectively navigate the system. In the first verse of Amir’s “Canvas,” he raps:

“Gotta buy the candy bar to get the golden ticket, that’s what tuition is

I could not imagine room and board, that’s ridiculous

Do not take it personal boy, that’s business.”

In addition to this, Jordan provides insight into the politics of respectability at play, that compel Black men to assimilate to predominantly white institutions’ norms, customs, and beliefs. These traditionally white ways of knowing, as he raps below, create an ideological rift among Black men, in determining how they should (or should not) carry themselves on campus:

“Politics, acknowledge it, but they still play the game

They playin’ with yo face, and they playin’ wit yo name

I swear this shit is feelin’ like it’s crabs in a barrel

They put you in a jam then they actin’ like a hero.”

Although the participants possess a deep knowledge of the structure of higher education, for some, their knowledge of the system came with a price. Hard lessons were learned as a result of systemic, cultural, and academic impediments on their respective journeys. Jordan recalls the moment in which he realized, in order to make inroads in the academy, it was impressed upon him, that he must assimilate in order to get ahead:

“I’m crying all alone like I failed myself

[…] They said if I want it all, I had to sell myself.”

While this experience may seem universal among minoritized groups in social institutions, like colleges and universities, Jordan insists that we reconsider what parts of ourselves we put on display for public consumption. Essentially, Jordan is asking other Black men, what they are willing to lose for the sake of participating in these institutions, that compel us to barter our culture for profit.

Amir reflects on some hard lessons of his own; namely, his difficult decision to drop out of college in 2010:

“The way up out this maze is [to] elevate my education

[…] Life comes in stages

when I first stepped to the plate, I could not Willie Mays it.”

While Amir has rebounded from this moment of perceived failure, he seems to rely on resistance capital (Solorzano and Yosso, 2002, Yosso, 2005), as a means of surviving another potentially repressive institution: The United States military. Amir raps about how his decision to join the armed forces, was fueled by the tuition assistance program:

“Nipsey taught me, ‘all money in, no money out’

Army tuition assistance and submission from my house.”

Thanks to his cultural knowledge of Nipsey Hussle, Amir was able to navigate multiple social institutions, banking on the military’s promise to pay for his next attempt at higher education, which, to date, includes two associate degrees, and a bachelor’s on the way. For this reason, Amir refers to the system of higher education in his song as, “the plug I finessed.” And rightfully so.

Though he does not offer a navigational strategy from his own non-traditional degree path, Landon acknowledges that the presence of Black spaces on campus – presumably, student organizations and the free-standing Black cultural center – reinforce his sense of belonging:

“I’m glad we got black spaces

Won’t for that, I would not even like school.

Similarly, Clyde recognizes the importance of predominantly Black spaces, as a means of navigating this new trap. In addition to being appointed as the graduate advisor of the Caribbean Student Association (pseudonym), Clyde also played a critical leadership role in another student-led Hip-Hop organization known as Crate Divers (pseudonym). During his time in the organization, he helped plan, organize, and implement a Hip-Hop symposium, in conjunction with the university archives. In his interview, Clyde states:

“As a third year Ph.D. student, [Crate Divers] gave me a platform I never thought I would have at [this university] […] I’ve been able to link with undergraduates, masters, and doctoral students, people of different races and genders, all because of Hip-Hop. [Crate Divers] has always been a safe space.”

Clyde’s active participation in these niche communities, reaffirmed his confidence in navigating the institution as a graduate student. Meanwhile, it is worth noting that the mere existence of spaces like these, however, are not enough to shield students from issues back home. Landon raps:

“But back home, everything is still anxious

Cannot afford it but I said I’ma try school

Ain’t nothing getting better for ma dukes

And my peers do not understand that

Ion even know if this the right school.”

While these circumstances were instrumental in his decision to step away from school, return home, and work a part-time job to continue providing financial support to his family, he came back to school and completed his bachelor’s degree in 2021. Similarly, Travis encountered impediments in his own academic journey, as he recounts a story of being placed on academic probation, following an alleged cheating incident:

“I had to get selfish, started out with just me

Got me some friends […]

I helped them all study […] got put on probation

Advisors do not help, they all hesitated

Dean’s list next year, now they want my good graces

Kissing my ass, congratulations.”

In a fit of justified rage toward a ubiquitous they (see: The Ubiquitous “They”) – which is, in this case a group of peers and ineffective academic advisors – Travis laments about not having adequate access to the resources needed to rectify his probationary academic status:

“I was down bad and they know that

Ain’t giving me the tools that I need to succeed

Hiding my major needs.”

In those moments where institutional structures – not to mention inter-peer relationships – seem to let these Black men down, it seems that Hip-Hop provides a space for them to feel confident and affirmed. In their interviews, participants were asked to complete the following sentence, using one word: As a Black man on campus, I feel __________.

Clyde: “empowered.”

Landon: “multifaceted.”

Amir: “like the shit.”

William: “powerful.”

Bryan: “justified.”

It is also worth noting that, as Black men on campus, they also feel targeted; as if they live under a microscope. Contrary to Travis’ sense of isolation in the wake of being placed on academic probation, this dyad of hypervisibility and invisibility is consistent with the literature about minority populations in schools (Reddy, 1998). Participants recall feeling “looked at or noticed” (Greg), “guarded” (Jordan), and “threatened” (Clyde), which compel them to lean heavily on their identities as Hip-Hop artists as source of healing and guidance. Amir raps:

“Lost in these books, Hip-hop that’s my compass

I’d be broke and lost without it, I’m just being honest.”

The act of writing, recording, and performing Hip-Hop music in college then, takes on a restorative quality. It is a transgressive act, designed to help the participants cope with the dissonance associated with remaining authentic in pursuit of educational opportunity. Ultimately, their ability to remain true to themselves and their craft, reflects the navigational influence Hip-Hop music provides the participants. When it comes to navigating the new trap, perhaps, Malcolm said it best:

“We showed up and showed out

No invitation, just innovation

[…] Now we all degree holders

Put the school on our shoulders

Campus legends, no question nigga.”

The ubiquitous “they”

Each of the participants offer scathing critiques of their institutions through their experiences as Black men on campus. However, rather than naming specific persons or entities that have c/overtly impeded their academic progress or symbolic violence (Richardson, 2011), the participants use their lyrics to create a ubiquitous they. That is, what I describe as, a composite character whose habits and dispositions reflect that of white supremacy and internalized racism. In many ways, they act as a foil to the participants’ lyrical protagonist. I use the term foil intentionally, as foil characters, at times, exist alongside the protagonist, rather than in direct opposition to them. In most instances, the foil characters exist to reflect and amplify the characteristics of the protagonist. To that end, the participants’ construction of a ubiquitous “they,” carries on the colloquial tradition of phrases like, “the man” – a derogatory term intended to represent the government, or some authority in a position of power (Lighter, 1997). In constructing this they-me dichotomy, the participants posit three unique perspectives on who the ubiquitous they represent: (a) purveyors of whiteness and white supremacy; (b) Black men who espouse the politics of respectability and internalized racism; and (c) the self, in relation to others.

First, the participants contend that there are discursive forces at play that support and perpetuate white supremacy. The participants describe these discursive forces as a collection of policies, procedures, histories of racial/ethnic inequality, and interpersonal interactions with white and other non-Black students whose presence on campus is consistently affirmed and validated. Because each of the participants currently attends or attend PWIs, it seems important that their lyrics provide insight into how the ubiquitous they propagates whiteness. For instance, Travis raps:

“I’m tryna feel safe in my own skin

Foot in the door, they will not let me in.”

Although he’s granted access into a PWI, he still feels as if they will not let him in – or, in other words, participate in the dominant culture on campus. Similarly, this culture of exclusion is depicted in Bryan’s hook on THREEdom’s “Hindsight 2020”:

“Lately I’ve been on the edge

I do not think you understand right now

They do not wanna see me as a man

So I’m going beast mode

Now I’m back at it again.”

For Bryan, being excluded from the dominant culture creates within himself, a sense of anxiety; a sentiment that is only exacerbated when he encounters a group of white locals, wielding a Confederate flag while studying at an off-campus coffee shop:

“A far cry outta my comfort zone

Outnumbered, I gotta feeling I’m home alone

[…] Freshman year, Summit Coffee when I seen that hate-filled flag

Had me stuck right to my seat like some Velcro pads.”

This incident, which took place in the days following the 2016 presidential election elicited within Bryan, a paralyzing fear of racialized acts of violence. Bryan speaks directly to other nonwhite, liberal college students who felt a sense of helplessness and desperation in the wake of Donald Trump’s victory. White, far right-wing conservatives, who felt emboldened by Trump’s virulent brand of racist rhetoric, now felt justified in their beliefs; returning to a more vitriolic expression of their white supremacist sentiments.

Although Bryan’s experience predates the tragically pivotal Unite the Right rally in Charlottesville at the University of Virginia, his anecdote represents the ways in which Black students were making sense of their presence at PWIs. To this point, Travis continues:

“They do not get it

They hate when I’m front of the class or make an appearance

You can catch me in the front row, getting these A’s,

Raising my hand, do not care if you hear it.”

“They do not want Black faces up at the top

[…] I am what I want me to be

Not who they think,

I’m not who they wanna see.”

While Bryan takes on a more reflective tone, Travis’ posture is more confrontational; transforming that negative energy received from historically racist opposition, into a culturally defiant pursuit of academic achievement. Landon goes a step further in his song, “BMOC,” when he raps:

“They glad to know me […] token in class

Gotta watch what they ask

I gotta take a seat in the front of the class

[They] think I’m an athlete, yeah,

I’m an athlete running these grades up on ya ass.”

Although he feels like a token Black man in his class, Landon uses this as a source of motivation; driving him to outperform his peers. Landon goes on to name the ubiquitous they he refers to above:

“All my classmates Asian or White.

Wanna know about a day in the life.

Wanna see what I say about rights.”

Rather than wallow in his perceived tokenization, Landon identifies his they – challenging these communities to reexamine their preconceived notions of what it means to be Black in higher education. These lines represent a sentiment felt by many Black students, who believe their opinions in class, while valid, are assumed by others to represent their entire race.

While my conceptualization of the ubiquitous they is anchored by racist and reductive notions of Blackness, it is also worth noting that the participants insist that Black people – Black men in this case – can also propagate internalized forms of oppression through respectability politics. For decades, Black feminist (White, 2001) and Black queer (Lane, 2019) scholars have led the discourse on intersectionality, the politics of respectability, and how the performance of whiteness, even as a means of self-preservation, will not, in fact, save us (Houston, 2015) hypervisibility in majoritarian environments – like colleges and universities that were not historically intended to serve communities of color. In the lyrics below, the participants begin to unpack the ways in which their physiology – which in this case, refers to their hair – exists as a point of contention and hypervisibility as they navigate campus life, rendering the charade of fitting in seem moot:

Greg: “Now I’m in a place where my hair is described like a felon’s.”

Jordan: “See a nigga wit a fro and suddenly they trouble

I cannot let nobody in like the NBA bubble.”

Greg, who began growing locs during his freshman year, and Jordan, who rocks a prominent afro, both offer these brief reflections on the ways in which their physical appearance is often policed from within their own community. In lieu of this, Jordan remains guarded; skeptical of, and ultimately distancing himself from, those who stereotype him because of the way he chooses to wear his hair. As isolating as this may be, it is an act of self-preservation in a space that is often at odds with his cultural ways of being.

In addition to this, Landon provides commentary on the perceived appropriateness of African American Vernacular English (AAVE) in the classroom:

“Let me tell y’all about English class

Cannot talk Ebonics, shit will not pass

Hooked on phonics, but these hooks mo’ honest

When I speak that jazz.”

While the previous examples imply the presence of a ubiquitous they, the subtext from Greg, Jordan and Landon read like cautionary tales to Black men, fraught with concern about being accepted within the dominant campus culture. Landon’s use of the word “honesty” is significant because it harkens back to literature that ranks authenticity among the pantheon of prerequisites for performing Hip-Hop culture (Low, 2011) in academic environments. This is especially important for Jordan as well, who continues his lyrical onslaught against Black men who selectively choose to distinguish themselves from the collective struggle for human rights:

“Look, I was down bad, could not see a way out

Askin’ what I’m finna do, all I heard was they doubt

Got so many faces, I do not know what they bout

Down for the cause till you need em, then they fade out

It’s these uppity niggas that never seen struggle

[…] Let that nigga stand next to Uncle Tom, bet I’m seeing double.”

Here, Jordan is effectively calling out Black men who, rather than prioritizing collectivism, revert to rugged individualism; whose idea of success is characterized by a proximity to whiteness. Jordan’s lyrics are consistent with other Black male writers like Damon Young of Very Smart Brothers, who, in 2017 wrote, “straight Black men are the white men of Black people.” Together, Young (2017) and Jordan both signify that cisgender heterosexual Black men, who face significant forms of oppression, also internalize behaviors from their oppressors that in turn, inform the way they marginalize the voices, experiences, and injustices against Black women and other minoritized groups. Jordan expounds on this sentiment in the hook of his song, “Funny How,” as he moves seamlessly between his critiques of multiple theys – the purveyors institutional racism and the Black men who condemn him for calling them out:

“Funny how they thought that I would fail, and I would not

Funny how they wanted me to fold, and I could not

Funny how they wanted me to change, but I should not

They wanted me to play a game they ain’t winning

Funny how they Black but tried to Black ball the kid

Funny how they cannot even admit to what they did

Funny how I’m standing tall after all this shit

Funny how I still ball, after all this shit.”

Finally, the participants used their mixtape contributions to define themselves in relation to the ubiquitous they. Rather than ascribe to a set of white, Eurocentric politics of respectability that mediate socially acceptable behaviors, the participants forged pathways in their music for the preservation of their culture. For instance, several participants made specific references to their hometowns, and.

Greg: “I’m from Macon, screaming east side ‘til I die.”

William: “A-t-l-a-n-t-a the west was where I laid boi

Took em out the city, made a nigga to playboy.”

Similarly, Malcolm of THREEdom made references to his hometown of Brooklyn in his ad-libs. This act of representing where you are from is a fundamental element of Hip-Hop culture and the identity of the emcee. When Landon follows up in his song by saying, “I want honor, not designer,” it symbolizes how he sees himself, not merely in relation to the ubiquitous they, but how he sets himself apart from the pack. To the emcee, it is not merely an honor to hail from their place of origin, it is essential to their knowledge of self. Ultimately, the participants are reclaiming their personhood by naming where they are from, and how that distinguishes them from the dominant culture on campus.

For Greg, however, it was not enough to simply name where he’s from; he provides context on what it means to call Macon, Georgia home and to be enrolled in college:

“I’m a mix between a gangsta and a businessman

So you never know what state I’m in.”

While vacillating between “gangsta” and “businessman” might seem complicated, it is merely contemporary manifestation of DuBois’ theory of double consciousness (Boxill, 2020); that is, the heightened sense of awareness Black people – and people of other minoritized identities – experience when navigating predominantly white spaces. Greg’s ability to code switch or, perhaps in this case, code mesh (Williams-Farrier, 2017) is essential to his survival. Owning who he is, as a result of being where he’s from, allows Greg to remain his authentic self, while enacting the knowledge necessary to reclaim some semblance of authority in academic spaces.

By possessing a deep knowledge of self, according to Hop scholars (Love, 2016), is a foundational pillar among the performative elements of Hip-Hop culture. While DJing, emceeing, breaking, and graffiti reflect Hip-Hop culture’s core modalities, knowledge of self is the element that connects them all. It is the transcendent thread that provides Hip-Hop artists across the modalities, with their style, confidence, and charisma. To that point, in their respective songs, Malcolm and Greg go so far as to refer to themselves as GOATS, or the greatest of all time:

Malcolm: “Real GOATs in the making

[…] rise above our station

hear us on every station, boi.”

Greg: “You cannot see me though, or feel me though

I’m Casper the fucking ghost, I am the fucking GOAT

Came in off a fucking boat

I cannot be humble no mo’.”

Such a declaration is not possible without a keen sense of self-awareness and aspirational capital (Yosso, 2005). Although the participants spend significant time naming, critiquing, and breaking down their opposition, they are not some amorphous, existential entity. Rather, they pose a serious threat to the social, political, and academic livelihood of these Black men. Thus, the act of creating Hip-Hop music is, what Jenkins (2016) might refer to as, the healing component – a spiritual salve for remaining true to oneself and one’s goals in moments of dissonance. Perhaps Malcolm illustrates the participants’ collective orientation to the ubiquitous they:

“Went from peasants to some Kingz

Went from Kingz to some Legendz

We’ve been fighting for our dreams

since we were freshmen like it’s Tekken.”

It is within that fight, through the art of Hip-Hop, participants can articulate who they are and hope to be, within a system of higher education; a system that often exists in opposition to the participants’ countercultural ways of being.

Put you on game

In addition to creating moments for self-knowledge and reflection on systemic oppression, internalized racism, and navigational capital, the mixtape allows the participants a profound opportunity to share their new knowledge with other Black men hoping to follow in their footsteps. KRS-ONE after all, proclaims to be hip is to know; hop is a movement (Price, 2017). Thus, the cultural phenomenon that is Hip-Hop, at its core, is about the ways in which historically marginalized communities communicate their knowledge about the world, how the world functions, and (re)imagining their places within and beyond it. In the spirit of KRS-ONE and Hip-Hop’s essential definition, the participants carry on this tradition, by leaving behind a roadmap for other young Black men that is as existential as it is practical. To pay it forward, the participants offer somewhat of a blueprint to Black youth who see higher education as a pathway to their personal and professional goals. To put one on game, in this context, is to share the gritty details of what the game is (e.g., higher education), and what that game has in store for those who dare to play.

Prior to offering his story of overcoming academic probation, Travis reflects on knowledge shared from his father – who was the first in the family to go to college. He raps:

“Pops said use that brain up in your head ‘fore you lose it

Now I just got so much to prove, and I ain’t losing.”

Not only does this speak to Travis’ concept of community and cultural wealth (Yosso, 2005), this admonishment from his father is a source of intrinsic motivation; a fire that fuels his persistence in the face of adversity; a reminder of why he inevitably, “cannot lose.” Travis, however, is not the only participant to invoke paternal wisdom. Amir, a father himself, begins his song with a skit featuring a short dialogue between him and his son:

Amir’s son: “Daddy?”

Amir: “Yes.”

Amir’s son: “Are you doing your homework?”

Amir: “I am! I love you!”

Both: [shared laughter].

Though Amir does not offer advice to his son in the form of an aphorism, by actively completing his homework in the presence of his son, he models, in real time, the habits and dispositions necessary for academic success. While his son may be too young to understand the difference between an associate and bachelor’s degree, he will still recall what it was like to bear witness to his father pursuing (and presumably achieving) a long-term, academic goal. For Amir, his success is reflected through the people in his life; the ones he holds close.

In reflecting on his experiences using his military service as an avenue for tuition assistance, Amir goes on to say:

“I came to school to die with a check, not debt

And Imma put the lil’ homies on up next.”

These lessons reverberate throughout THREEdom’s music as well. Bryan’s third verse on “Hindsight 2020” concludes with a bold statement about the power of paying it forward:

“Remember every step forward gotta reach yo hand back

Shouldn’t even have to wait for you to be an old head to understand that.”

Malcolm’s attempts to pay it forward are a bit more foreboding, admonishing listeners to be wary of those who would relish in their downfall, while also being confident enough to put those naysayers in their place. Ultimately, this unwillingness to falter at the behest of foes, for Malcolm, is a prerequisite for leaving his mark on campus:

“Late nights, long days, took some Ls, never sweat em

Had some haters, had to check em

Made mistakes then correct em

[…] Made a mark so big, they will not forget us.”

While he does not provide specific examples of what those long nights entail, the mistake he’s made, or how he keeps his opposition in check, Amir, in turn, offers a detailed rundown of his academic missteps, and his newfound inroads to success in the classroom:

“Dropped out, my momma cried, it burned me deep

Fast forward 10 years, I’m on my 3rd degree

Friendly faces see that ain’t no slave in me.

I’m married, working on my Bachelor’s, this one gon’ be free

Classes 4 by 4 like Jeeps, 4 classes every 9 weeks

Got a wife to please and son to feed.”

This stanza reflects both a low point in Amir’s higher education experience and how he’s risen from those depths. In just a few lines, Amir provides insight into who was, and continues to be, most affected by his journey through higher education – namely his mother, wife, and son. The detail with which he describes his coursework speaks to the transgressive appeal of his music.

By sharing his newly acquired knowledge of how colleges, universities, and the US military tuition assistance program functions, Amir creates a moment for Black men who aspire to infiltrate historically repressive institutions to pursue their goals, while holding their families close. Similarly, Bryan of THREEdom adds:

“Aye tell me what’s the plan

Making sure my people straight

I gotta chase a band.”

This declaration from Bryan provides subtle commentary on the myth of the American meritocracy; that is, the notion that people’s social status becomes increasingly dependent upon an individual’s level of education (Moore, 2004; Liu, 2011). In these lines, Bryan posits that having a plan – presumably a plan to pursue and complete a college degree – will help him secure “a band,” and social mobility more broadly. From Bryan, completing his degree is a means for making sure he can meet the financial needs of the people in his family circle.

Finally, Greg offers words of encouragement to Black men who may be struggling to rationalize their academic goals with the time it takes to complete them. Greg raps:

“I got a dream to flood the streets.

With peace signs,

But the finish line is way too far away

[…] Do not be scared to be great.”

This charge to be great is grounded in Duncan-Andrade (2009) conceptualization of critical hope; that is, an audacious hope that, “demands that we reconnect to the collective by struggling alongside one another, sharing in the victories and the pain,” (p. 190). Based on Greg’s lines, greatness is not merely some platitude devoid of context. Instead, daring to be great requires an acknowledgement of one’s social condition and circumstance. It is the basis for being able to hope when it seems as though all hope is lost.

Limitations & looking ahead

While this project proved to be uniquely engaging and widely accessible, there are indeed growing pains associated with establishing a new methodology. Though noble in its intentions, mixtaping is messy. Corralling multiple artists from various regions of the country, who have no chemistry or prior knowledge of each other’s work, makes the likelihood of establishing a unified voice distinctly difficult. Unlike scholars who strive to create a cohesive co-authored article or edited volume of text, Hip-Hop artists in this academic context, may be interested in distinguishing their voices from their counterparts rather than fusing them. After all, with the exception of THREEdom, the participants did not have an opportunity to meet, listen to, or learn from one another beyond their engagement with the finished product. While this sort of engagement is beyond the scope of this project, I believe there is value in hip-hop artists being mutually engaged in the creation of a meaningful body of work.

In the case of our mixtape, each participant responded boldly to the prompt in his own unique fashion, making for a multidimensional perspective on the Black male experience in college. The limitation as it relates to intergroup chemistry, however, was most evident when faced with making executive decisions about the mixtape (e.g., the title, cover art, release date, etc.). Perhaps that lack of chemistry was due, in part, to ineffective modes of communication. As the primary researcher, I did not make consistent attempts to encourage conversation among the participants. In addition, as stated above, the participants were granted access to interview audio and files, as well as song lyrics and audio files. However, there was no evidence that the participants took it upon themselves to explore those documents or reach out to the other participants via email on their own volition. In the future, I will work harder to build trust, not just among myself and the participants, but among them as well. Hip-Hop, in many ways, is about building and sustaining community. And it was clear, as the study progressed, that the only meaningful connection the participants had to one another was me. Thus, in the future, I encourage scholars to create alternate spaces outside of the shared google folder, for the participants to be connected and engage one another throughout the duration of the study. I will share links their social media pages and previously recorded music; a group chat or text thread, to communicate pertinent updates; and establish intermittent check-ins, so I can share my initial findings and receive feedback, as a means of holding myself accountable to publishing the most accurate interpretation of the participants’ voices.

In addition to improving communication among the participants, I would’ve hoped to recruit Black men from multiple institutional types. Although the colleges these young men represent are spread across the American south, each of them currently attends a PWI or community college. While Clyde, one of the two graduate student participants in the study, attended an HBCU for his undergraduate degree, I believe the study would have benefited from HBCU greater representation from current HBCU students. Travis even lamented in “Cannot Lose” that he wanted to “apply to Howard to look for a change” because of the racial/ethnic homogenization at his current institution. Comparatively, reflections on the HBCU experience from a currently enrolled HBCU student, would’ve provided the study with another valuable lens, through which we may come to understand the Black male experience in higher education. That is not to discredit the other opinions that were posited in these songs. After all, having representation from Black men enrolled in online, community college, post-baccalaureate, and certificate programs is a significant accomplishment considering our small sample size. However, if given more time to complete this project, I would not forge ahead without an HBCU emcee.

With regard to representation, I was quite wary of naming the institutions the participants attend/attended. Identifying marks such as these, though perhaps influential to their craft, I was hoping to spare them any collateral backlash that may come from any unsavory misinterpretations of their work. Similarly, I chose to hide the participant’s hometowns, again, in an attempt to preserve as much anonymity as possible. It is likely that a participant’s individual artistic influences, sensibilities, and expressiveness could undermine the veneer of safety my pseudonyms or aliases may provide, I also understand that a prerequisite for participation in hip-hop culture is authenticity – knowledge of self. For all of my efforts as a researcher, the rapper in me understands that every opportunity we have to write and record is another chance to put on for where you are from! And no amount of scholarly discretion, nor informed consent form, can contain one’s ability to use their voice; to represent themselves as they see fit. In the future, depending on the nature of the research question, I may make a more concerted effort to at least provide room in the discourse for a meaningful discussion of the participant’s hometowns and lyrical influences. This will, at least, preserve as much anonymity as possible without inadvertently identifying an individual participant.

I also acknowledge that this project was executed amid the COVID-19 pandemic. This is significant for several reasons. Although video conferencing via Zoom made it possible to reach a wider audience of prospective participants, it was not abundantly clear that each participant had consistent access to recording equipment and audio engineering technology. The IRB-approved participant recruitment materials clearly stated that participants will be asked to record a song, however, it was unclear whether recording materials, instrumentation, or engineering assistance would be provided by my institution, or if it would be required by the participants themselves. For some of the participants, this might’ve been an additional, out-of-pocket expense, if they had to pay for professional audio engineering services. Although I asked thorough questions related to why they write, record, and perform Hip-Hop in college, I did not pose specific questions as to how they go about it. Was I asking them to perhaps venture outside of their homes, using another person’s recording equipment and voluntarily place themselves at risk of exposure to COVID-19, just for the sake of recording a niche mixtape? Certainly, my intent was not to put the participants in harm’s way. Research always requires special attention to detail; but during a global health crisis, those details may very well be a matter of life and death. Thankfully, none of the participants were harmed as a result of this project. However, moving forward, it is important to supply participants with PPE and other safety equipment necessary to execute the task before them. As arts-informed inquirers, we must ensure the health and safety of our participant cohorts.

Conclusion

Mixtaping as a research method yielded unique results. As stated above, the compilation music project, created by the participants revealed that Black men – especially those who identify as Hip-Hop artists: (a) regard their institutions as the “new trap”; (b) define themselves in relation to a ubiquitous “they”; and (c) use their lyricism to pay it forward, or “put you on game.” That is not to say that the perspectives described by the participants would not be captured in more conventional qualitative methods, like interviews and focus groups. However, when scholars approach inquiry through the prism of culturally relevant, emancipatory research design, the study becomes more than a study. It is an opportunity for healing and critical hope. As fascinating as the results may be, the true value in this study is its accessibility to audiences beyond the academy. While results published in this article are borne of my own lenses, I acknowledge that there are indeed, blind spots in my interpretations. However, because Hip-Hop is public pedagogy, I am inspired in knowing that these beats, rhymes, and reflections on campus life are open to interpretation from an audience who, for far too long, have been denied access to contemporary discourse within the ivory tower.

Data availability statement

The datasets presented in this study can be found in online repositories. The names of the repository/repositories and accession number(s) can be found at: https://donovanlivingston.bandcamp.com/album/k-e-y-s-knowledge-essential-for-your-success.

Ethics statement

The studies involving humans were approved by Wake Forest University Research & Sponsored Programs. The studies were conducted in accordance with the local legislation and institutional requirements. The participants provided their written informed consent to participate in this study. Written informed consent was obtained from the individual(s) for the publication of any potentially identifiable images or data included in this article.

Author contributions

The author confirms being the sole contributor of this work and has approved it for publication.

Conflict of interest

The author declares that the research was conducted in the absence of any commercial or financial relationships that could be construed as a potential conflict of interest.

Publisher’s note

All claims expressed in this article are solely those of the authors and do not necessarily represent those of their affiliated organizations, or those of the publisher, the editors and the reviewers. Any product that may be evaluated in this article, or claim that may be made by its manufacturer, is not guaranteed or endorsed by the publisher.

References

Adaso, H. (2017). The history of trap music. Available at: https://www.thoughtco.com/history-of-trap-music-2857302 (Accessed November 27, 2020).

Adjapong, E., and Levy, I. (2021). Hip-hop can heal: addressing mental health through hip-hop in the urban classroom. New Educ. 17, 242–263. doi: 10.1080/1547688X.2020.1849884

Allen, Q. (2020). (In)visible men on campus: campus racial climate and subversive black masculinities at a predominantly white liberal arts university. Gend. Educ. 32, 843–861. doi: 10.1080/09540253.2018.1533924

Boxill, B. (2020). W.E.B. DuBois and William James on double consciousness. J. Soc. Philos. 54, 316–332. doi: 10.1111/josp.12329

Bridgeforth, J. (2018). “Examining campus climate for African American males at predominantly white institutions” in The handbook of research on black males: quantitative, qualitative, and multidisciplinary. eds. T. S. Ransaw, C. P. Gause, and R. Majors (East Lansing, MI Michigan State University Press), 441–455.

Brooms, D. R. (2019). Not in this alone: black men’s bonding, learning, and sense of belonging in black male initiative programs. Urban Rev. 51, 748–767. doi: 10.1007/s11256-019-00506-5

Burge, G., Godinho, M. G., Knottenbelt, M., and Loads, D. (2016). “…But we are academics!” a reflection on using arts-based research activities with university colleagues. Teach. High. Educ. 21, 730–737. doi: 10.1080/13562517.2016.1184139

Crenshaw, K. (2002). “The first decade: critical reflections, or ‘a foot in the closing door’” in Crossroads, directions and a new critical race theory. eds. F. Valdes, J. McCristal Culp, and A. Harris (Philadelphia, PA: Temple University Press), 9–31.

Dancy, T. E., and Brown, M. C. (Eds.) (2012). African American males and education: researching the convergence of race and identity Ser. contemporary perspectives on race and ethnic relations. Charlotte, NC: Information Age Pub.

Duncan-Andrade, J. (2009). Note to educators: hope required when growing roses in concrete. Harv. Educ. Rev. 79, 181–194. doi: 10.17763/haer.79.2.nu3436017730384w

Emdin, C., Adjapong, E., and Levy, I. (2018). #hiphoped: The compilation on Hip-Hop Education. Brill Sense.

Gitonga, P. N., and Delport, A. (2015). Exploring the use of hip-hop music in participatory research studies that involve youth. J. Youth Stud. 18, 984–996. doi: 10.1080/13676261.2015.1020929

Green, A. (2016). The cost of balancing academia and racism. The Atlantic. Available at: http://www.Theatlantic.com/education/archive/2016/01/balancing-academia-racism/424887/ created from duke on 2023-08-08 00:55:31.

Harper, S. R. (2009). Niggers no more: a critical race counternarrative on black male student achievement at predominantly white colleges and universities. Int. J. Qual. Studi. Educ. 22, 697–712. doi: 10.1080/09518390903333889

Harper, S. R. (2012). Black male student success in higher education: a report from the National Black Male College Achievement Study. Philadelphia: University of Pennsylvania, Center for the Study of Race and Equity in Education.

Harper, S. R. (2013). Am I my brother's teacher? Black undergraduates, racial socialization, and peer pedagogies in predominantly white postsecondary contexts. Rev. Res. Educ. 37, 183–211. doi: 10.3102/0091732X12471300

Harper, S. R., and Museus, S. D. (2007). Using qualitative methods in institutional assessment Ser. New Dir. Inst. Res. 2007:5. doi: 10.1002/ir.227

Harper, S. R., and Quaye, S. J. (2007). Student organizations as venues for black identity expression and development among African American male student leaders. J. Coll. Stud. Dev. 48, 127–144. doi: 10.1353/csd.2007.0012

Harper, S. R., and Wood, J. L. (Eds.) (2016). Advancing black male student success from preschool through PH. D (First). Sterling, VA: Stylus Publishing.

Hines, E. M., Harris, P. C., Mayes, R. D., and Moore III, J. L. (2020). I think of college as setting a good foundation for my future: black males navigating the college decision making process. J. Multicult. Educ. 14, 129–147. doi: 10.1108/JME-09-2019-0064

Hines, E. M., Mayes, R. D., Harris, P. C., and Vega, D. (2023). Using a culturally responsive MTSS approach to prepare black males for postsecondary opportunities. Sch. Psychol. Rev. 52, 357–371. doi: 10.1080/2372966X.2021.2018917

Houston, S. (2015). Respectability will not save us: Black Lives Matter is right to reject the “dignity and decorum” mandate handed down to us from slavery https://Www.Salon.Com/2015/08/25/Respectability_will_not_save_us_black_lives_matter_is_right_to_reject_the_dignity_and_decorum_mandate_handed_down_to_us_from_slavery/

Jones, A. (2010). Not some shrink-wrapped beautiful package: using poetry to explore academic life. Teach. High. Educ. 15, 591–606. doi: 10.1080/13562517.2010.491902

Kaluža, J. (2018). Reality of trap: trap music and its emancipatory potential. J. Media Commun. Film 5, 23–41. doi: 10.22492/ijmcf.5.1.02

King, T., and Palmer, R. T. (2014) in Building on resilience: models and frameworks of black males' success across the p-20 pipeline. ed. F. A. Bonner (Sterling, VA: Stylus Publishing).

Ladson-Billings, G. (1995). Toward a theory of pedagogy. Am. Educ. Res. J. 32, 465–491. doi: 10.3102/00028312032003465

Lane, N. (2019). The black queer work of ratchet: race, gender, sexuality, and the (anti)politics of respectability. New York, NY: Springer International Publishing AG.

Leggo, C. (2008). “Astonishing silence: knowing as poetry in a” in Handbook of the arts in qualitative research: perspectives, methodologies, examples, and issues. ed. L. Cole (London, UK: Thousand Oaks, CA: Sage Publications), 166–175.

Levy, I. (2021). “Healing in collaboration with school counselors: hip-hop and spoken word poetry” in Critical pedagogy for healing: paths beyond wellness, toward a soul revival of teaching and learning. eds. T. Kress, C. Emdin, and R. Lake (London, UK: Bloomsbury Publishing Plc), 81–87.

Levy, I. P., Emdin, C., and Adjapong, E. (2022). Lyric writing as an emotion processing intervention for school counselors: hip-hop spoken word therapy and motivational interviewing. J. Poet. Ther. 35, 114–130. doi: 10.1080/08893675.2021.2004372

Liu, A. (2011). Unraveling the myth of meritocracy within the context of US higher education. High. Educ. 62, 383–397. doi: 10.1007/s10734-010-9394-7

Livingston, D. (2023). Beats, rhymes, and college life: making a case for mixtape methodology in higher education research. Int. J. Qual. Stud. Educ. 36, 1–12. doi: 10.1080/09518398.2022.2135038

Loads, D. (2009). Putting ourselves in the picture: art workshops in the professional development of university lecturers. Int. J. Acad. Dev. 14, 59–67. doi: 10.1080/13601440802659452

Love, B. (2016). Complex personhood of hip hop & the sensibilities of the culture that fosters knowledge of self & self-determination. Equity Excell. Educ. 49, 414–427. doi: 10.1080/10665684.2016.1227223

Low, B. E. (2011). Slam school: Learning through conflict in the hip-hop and spoken word classroom. Stanford, Calif: Stanford University Press.

McCarty, T., and Lee, T. (2014). Critical culturally sustaining/revitalizing pedagogy and indigenous education sovereignty. Harv. Educ. Rev. 84, 101–124. doi: 10.17763/haer.84.1.q83746nl5pj34216

McGowan, B. L. (2017). Visualizing peer connections: the gendered realities of African American college men's interpersonal relationships. J. Coll. Stud. Dev. 58, 983–1000. doi: 10.1353/csd.2017.0079

McGowan, B. L. (2018). Unanticipated contexts for vulnerability: an exploration of how black college men made meaning of a research interview process involving sensitive topics. J. Men Stud. 26, 266–283. doi: 10.1177/1060826518769073

McLean, K. C., Lilgendahl, J. P., Fordham, C., Alpert, E., Marsden, E., Szymanowski, K., et al. (2018). Identity development in cultural context: the role of deviating from master narratives. J. Pers. 86, 631–651. doi: 10.1111/jopy.12341

Moore, R. (2004). Education and society: issues and explanations in the sociology of education. Cambridge, England: Polity Press.

Nielsen, L. (2008). “Lyric inquiry” in Handbook of the arts in qualitative research: perspectives, methodologies, examples, and issues. ed. A. L. Cole (Thousand Oaks, CA: Sage Publications), 93–102.

Paris, D. (2012). Culturally sustaining pedagogy: a needed change in stance, terminology, and practice. Educ. Res. 41, 93–97. doi: 10.3102/0013189X12441244

Petchauer, E. (2007). “Welcome to the underground”: portraits of worldview and education among hip-hop collegians. Diss. Abstr. Int. 68, iii–iv. (UMI. 3271452)

Petchauer, E. (2017). Framing and reviewing hip-hop educational research. Rev. Educ. Res. 79, 946–978. doi: 10.3102/0034654308330967

Price, W. (2017). In his own words: KRS one – definition of hip hop ⋆ global Texan chronicles. Available at: https://globaltexanchronicles.com/words-krs-one/ (Accessed November 27, 2020).

Reddy, M. (1998). Invisibility/hypervisibility: the paradox of normative whiteness. Transform. J. Incl. Scholarsh. Pedagog., 9, 55–64. Available at: http://www.jstor.org/stable/43587107 (Accessed November 27, 2020)

Rhoden, S. (2018). Building trust and resilience among black male high school students: boys to men. 1st Edn Routledge Available at: https://doi-org.proxy.lib.duke.edu/10.4324/9781315159089.

Richardson, C. (2011). “Can’t tell me nothing”: symbolic violence, education, and Kanye West. Pop. Music Soc. 34, 97–112. doi: 10.1080/03007766.2011.539831

Rogers, T., and Mitchell, D. (2022). Hidden identity: a constructivist grounded theory of black male identity development at historically black colleges and universities. Qual. Rep. 27, 2251–2277. doi: 10.46743/2160-3715/2022.5718

Solórzano, D. (1997). Images and words that wound: critical race theory, racial stereotyping and teacher education. Teach. Educ. Q. 24, 5–19.

Solórzano, D. (1998). Critical race theory, racial and gender microaggressions, and the experiences of Chicana and Chicano scholars. Int. J. Qual. Stud. Educ. 11, 121–136. doi: 10.1080/095183998236926

Solórzano, D., and Yosso, T. (2001). Critical race and LatCrit theory and method: counterstorytelling Chicana and Chicano graduate school experiences. Int. J. Qual. Stud. Educ. 14, 471–495. doi: 10.1080/09518390110063365