Survival Foreign Language Acquisition Strategies During the Emergency Remote Learning: An Exploratory Study in Molding Indonesian Students’ Creativity

- 1English Department, Universitas Islam Negeri Antasari, Banjarmasin, Indonesia

- 2English Department, Universitas Muhammadiyah Banjarmasin, Banjarmasin, Indonesia

- 3Bahasa Indonesia Education Department, Universitas Lambung Mangkurat, Banjarmasin, Indonesia

Being a foreign language, mastery of English acquisition is hard for Indonesian learners. The transformation of teaching and learning in the condition of the COVID-19 outbreak even makes the teaching-and-learning is more difficult since they previously rely on face-to-face interaction and listening to teachers as the primary source of learning with unconvincing result. This article explores how undergraduate students cope up with emergency remote learning. Using exploratory research design, the students learning strategies are identified. Sixty-four university students who experienced blended learning using Google Classroom for one semester were recruited to participate in the research. A questionnaire and interview were used to collect the data. The questionnaire was developed to examine the kinds of effective strategies employed by the students. The interview aimed to detail their responses so their strategies can be mapped clearly. The research findings showed that some learning strategies, such as social and cognitive strategies, are more favorable than others during the pandemic. The condition requires them to make some changes; even some students found some new techniques for learning. At the end of the article, some implications for implementing future blended or online learning are highlighted.

Introduction

Individual efforts and active participation in learning are essential factors in the success of second language learning (Lamb, 2004; Alfian, 2018). During the outbreak of COVID-19, universities sent students home (Demuyakor, 2020; Morgan, 2020; Xue et al., 2020), which eventually required them to adapt to the new learning condition. Social and physical restrictions during the pandemic did not allow face-to-face meetings. Consequently, online learning becomes the possible choice to deal with the current situation and ensure students’ safety. According to Hurd (2006), online or distance learning craves greater self-regulation, so the students need to be more responsible for their learning. They need to improve their self-management, including managing their learning strategies, to learn in the online environment successfully.

Indonesia confirmed the first COVID-19 case in March 2020 (The Jakarta Post, 2020a). Schools and universities were asked to be temporarily closed no longer after the announcement. This situation forced them to change the mode of learning from offline to online. It was reported that online learning encountered some problems, such as the students got confused to adjust to because they never experienced it previously (The Jakarta Post, 2020b). Carrillo and Flores (2020) summarize that online learning deals with some challenges, for instance, insufficient facilities for online teaching and learning, inexperienced teachers, the complex environment at home, and lack of mentoring and support. The last challenge requires the students to be more active in learning to survive online learning.

Regardless of some emerging challenges due to the crisis of COVID-19, it also brings possibilities to change existing practice (Bryson and Andres, 2020). Students develop their learning autonomy because they need to use different online tools to support their learning (Sepulveda-Escobar and Morrison, 2020). A study conducted by Supiani et al. (2020) found that students have to become more independent to achieve their learning goals during the pandemic successfully. Since they become more autonomous, they also need to find their learning strategy. Huang (2018, p. 647) mentions that “learning is situated and learning strategies are derived from the context.” It means that students’ learning strategy is significantly affected by the current situations and conditions they are dealing with.

Previously, the teaching and learning in many universities in Indonesia relies on face-to-face meeting. Tanjung (2018) argued that many students in Indonesia were not well-familiar with learning strategies for their dependency on lecturers. The shift from offline to online due to the COVID-19 outbreak changes this habit. Students are forced to be more independent. Amir et al. (2020) reported that most students preferred classroom learning over online learning, but many of them agreed that they could adjust their learning strategies during the implementation of study from home regulation. They even experienced the efficiency and the flexibility of online learning. These findings lead to an argument that the transition from online to offline brings possibilities that students develop and change their learning strategies when they become more independent.

Although there have been some previous studies related to students’ learning strategies during the COVID-19, not many of them focuses on discussing the changes and adaptation of the strategies. In addition, study that concerning the Indonesian context regarding this topic is also scarcely found. Therefore, this study aims to find out how students can find solutions and deal with learning difficulties in the remote learning context. This present research focuses to answer these two research questions (1) What are language learning strategies used by the students during the emergency remote learning? and (2) How do the students’ adapt their learning strategies due to online learning during the emergency remote learning?

Literature Review

Language Learning Strategies in a Foreign Language Context

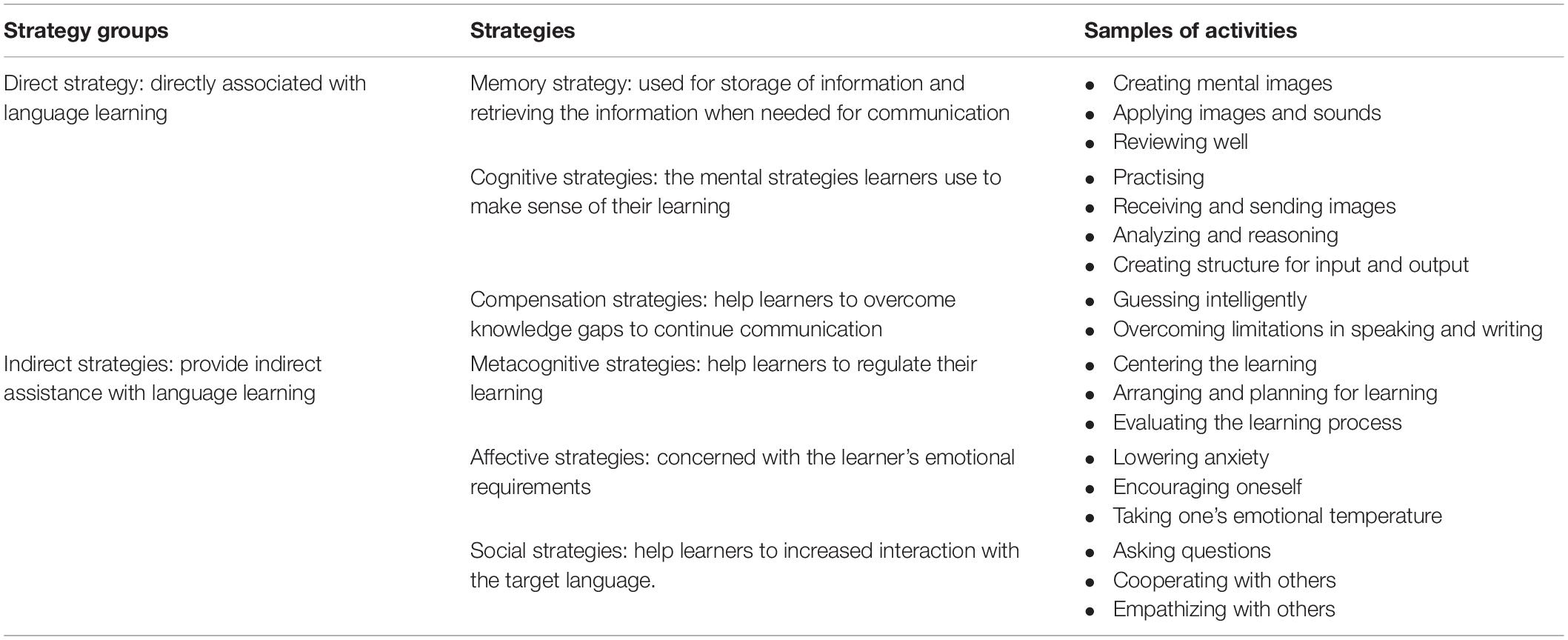

The aim of language learning strategies is oriented toward the development of communicative competence. Oxford divides language learning strategies into two main classes, direct and indirect. Language learning strategies are classified into six categories arguing that many different strategies can be used by language learners (Oxford, 1990): (a) metacognitive techniques for organizing, focusing, and evaluating one’s learning; (b) affective strategies for handling emotions or attitudes; (c) social strategies for cooperating with others in the learning process; (d) cognitive strategies for linking new information with existing schemata and for analyzing and classifying it; (e) memory strategies for entering new information into memory storage and for retrieving it when needed, and (f) compensation strategies (such as guessing or using gestures) to overcome deficiencies and gaps in one’s current language knowledge.

Direct learning strategies are directly associated with language learning (Chuin and Kaur, 2015). Those strategies involved the mental processing of the language (Oxford, 1990). Memory, cognitive, and compensation strategies belong to this category. On the other hand, Chuin and Kaur (2015) explain that indirect learning strategies do not directly help learners during the language learning process. Examples of these strategies are metacognitive, social, and practical strategies. Having high motivation, for example, is not counted as a mental processing activity when we are learning a language. However, because of the trigger, the students continuously learn the language.

In Oxford’s system, metacognitive strategies help learners to regulate their learning. Affective strategies are concerned with the learner’s emotional requirements, such as confidence, while social strategies lead to increased interaction with the target language. Cognitive strategies are the mental strategies learners use to make sense of their learning, memory strategies are those used to store information, and compensation strategies help learners overcome knowledge gaps to continue communication. In the foreign language learning context, research findings regarding which strategies students use mainly show a different result. Chuin and Kaur (2015) reported that metacognitive, social, and cognitive strategies were in the top three for the ranking among other strategies. This result was almost the same as a study conducted by Rustam et al. (2016) in the Indonesian setting, which concluded that metacognitive was the dominant learning strategy used by the students. However, Chang and Liu (2013) found that compensation and metacognitive were the most used ones. Although metacognitive always become the top rank, there is no fixed position for each strategy. Different contexts and participants will affect different results since learning strategies are related to individual factors and preferences. Adopting Saks and Leijen’s (2018) summary of language learning strategies, Table 1 clearly presents the groups, strategies, and sample of activities.

The students’ choices for learning strategies are affected by some factors, including cultural values (Chamot, 2004; Aktaş, 2012; Li and Wang, 2015; Raymond and Choon, 2017). Aktaş (2012) explains that students who grow in individualist culture will prefer to learn in the modes of abstract conceptualization and active experimentation. Meanwhile, those who hold collectivist values will favor tangible experience and reflective observation as learning approaches. Chamot (2004) suggests that cultural and contextual factors should become a consideration for teachers to find out their students learning strategies preferences. Previous research conducted by Fatimah et al. (2021) also yields that cultural beliefs affect students preferences in learning. Therefore, understanding students’ cultural backgrounds can help researchers better understand their reasons for using particular learning strategies.

Students’ Language Learning Strategies During the COVID-19 Pandemic

Since COVID-19 was announced as a pandemic, it forced schools to close and start online learning. This sudden change, of course, is not predicted, which eventually transformed the learning mode from face-to-face to remote learning without proper preparation. The digital transformation is not a new issue in education, but the presence of COVID-19 makes the trial for the situation faster. Adedoyin and Soykan (2020) list some factors which possibly become the challenges for digital transformation during COVID-19, including technology, socio-economic factor, human and pet intrusion, digital competence, and heavy workload. It is normal that when asking about the problem of online learning, both teachers and students in some countries, for example, in Indonesia, will talk about bad internet connections. Low economic students will also get difficulty affording broadband connections. In addition, not all teachers or students have good digital competence when using digital devices for online learning. These all examples of conditions then require students to make some changes to the way they learn.

The sudden change of the learning mode migration, from offline to online, of course also affected both teachers and students in the teaching and learning process. Pokhrel and Chhetri (2021) who conducted a literature review on the impact of COVID-19 on students’ teaching and learning found out that learners with a fixed mindset struggled to adjust, whereas learners with a growth mindset could quickly adapt to a new learning mode. Supiani et al. (2020) investigated how two international students adapt their learning strategies during the pandemic. Their findings yield that the restriction during the COVID-19 has different effects per different learners’ personalities. The introverted students tended to be less anxious in dealing with new situations compared to the extroverted ones. It is due to the habit of learning having by the introverted student, which made her have no problem with physical and social restrictions. The extrovert one was used to learning with their friends, so she felt lonely when studying at home alone. However, both students had a similar experience that they became more autonomous in learning. Rahiem (2021) figured out that university students remained motivated to study from home. Their motivation was driven by these three factors: personal, social, and environment. The personal factors include some sub-variables such as challenge, curiosity, self-determination, satisfaction, and religious commitment. The social factors cover some aspects such as relationships, inspiration, and well-being of self and others. Last, the environmental factors are related to facilities and conditioning. She concluded that those factors made the university students still committed to their studies.

Methodology

Research Design and Research Participants

The present research used an exploratory research design. This design allows researchers to investigate a problem, which is not well research previously. The participants were 65 English department students of a state Islamic University in South Kalimantan, Indonesia. They were 27 males (42.2%) and 37 females (57.8%). Those students came from two classes. When this study was carried out, they were in the fifth semester. Most of them are about 20 years old. They had studied English for almost 8 years since most of them started to learn English at junior high school. Some even got English classes since elementary school. Those 64 students enrolled on one of the researcher classes so she had access to invite them to join this research. Before the research, the participants had been informed that all the data collected will be used for publication. They also had been told that their names would be replaced with pseudonyms to keep their privacy.

Data Collection and Analysis

The data were collected by using two main instruments: a questionnaire and an interview. The questionnaire was developed by adapting the six language learnings strategies classification from Oxford (1990). The questionnaire consisted of 25 close-ended questions. Those questions were divided into memory strategies (3 items), cognitive strategies (4 items), metacognitive strategies (4 items), compensation strategies (2 items), affective strategies (8 items), and social strategies (4 items). In each item, every strategy was listed, so the students only needed to click on the learning strategies they experienced during the COVID-19 crisis. Some of those strategies have been modified to meet the online learning environment. In addition, one open question was also provided so the students could mention their strategies, which were not mentioned in the close-ended items. The questionnaire was administered online by using Google Form. One of the researchers shared the Google form with the students’ WhatsApp group.

The interview was intended to answer the second research question regarding how the students adapt their learning strategies during the COVID-19, as well as to collect additional data based on the result of the questionnaire. Not all participants were recruited for the interview, but only those students who filled the open-ended question. It was based on the consideration that the strategies they listed in the open-ended question was unique and could lead to a new insight. After listing the name of the interviewees, each of them was contacted to get their permission. Ten out of seventeen students agreed to have an interview by phone. The interview was conducted in Bahasa Indonesia so the participants could freely express their ideas without language barriers. They were informed that the conversation was recorded. During the interview, one of the researchers asked some detailed questions, such as how long they had used those strategies, whether they used them only during the COVID-19 pandemic, and whether they modified their learning strategy during the study from home.

The questionnaire data was analyzed using descriptive statistics to answer the first research question about the kinds of strategies used by the students during the pandemic. The interview result was transcribed and translated into English. The transcription, then, were coded and thematic analysis was used to interpret the data.

Results

This section is intended to answer two research questions, which are (RQ1) What are language learning strategies used by the students during the emergency remote learning? and (RQ2) How do the students’ adapt their learning strategies due to the online learning during the emergency remote learning?

Research Questions #1

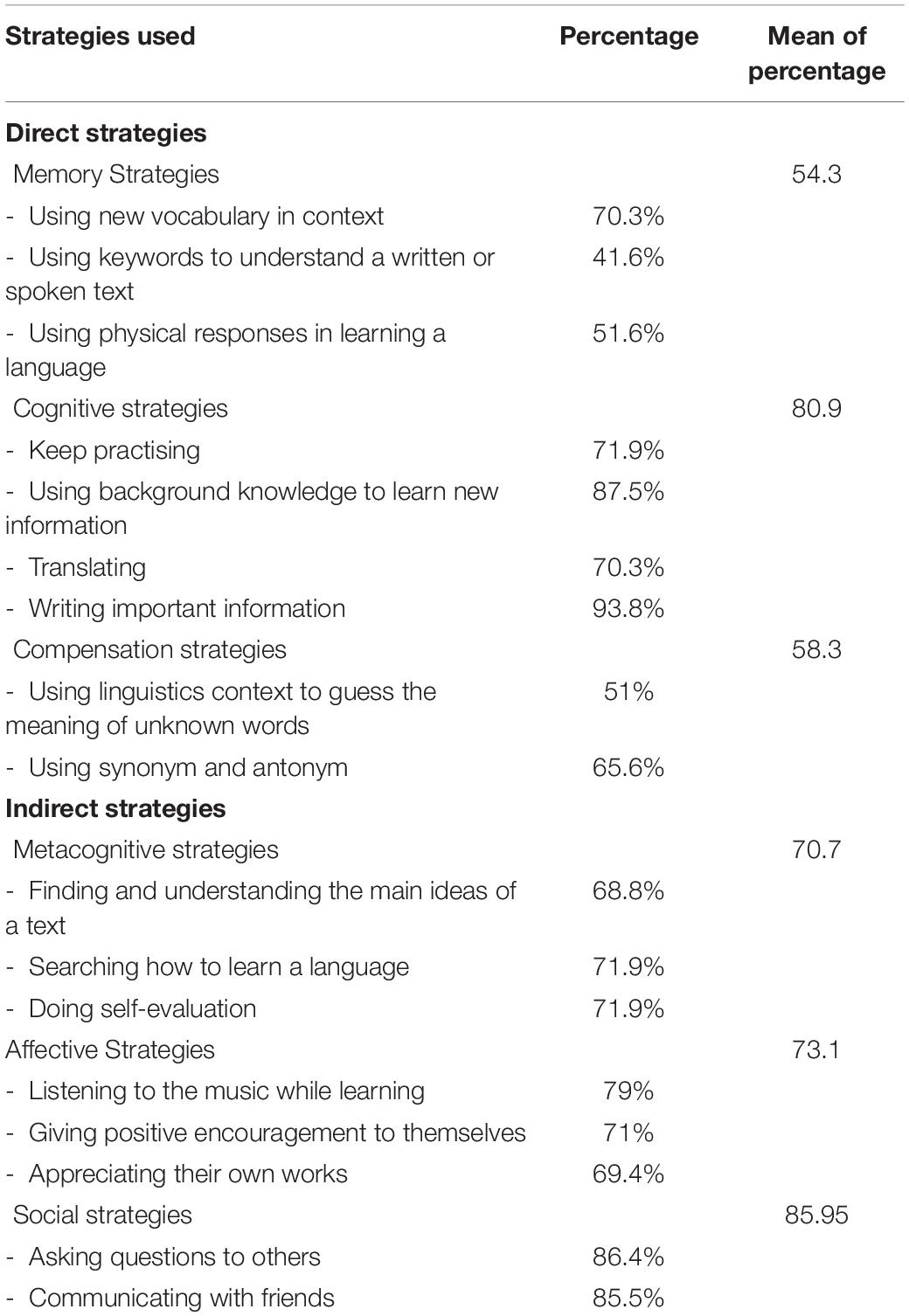

The answer to this question is mainly gained from the result of the questionnaire. The students still use all the language learning strategies during the study from home. Table 2 displays the most frequently used strategies by the students during the COVID-19 outbreak.

Table 1 shows that there are seventeen strategies chosen by the students. Looking at the mean of the percentage, we can identify that social and cognitive strategies are the most used strategies employed by the students during study at home.

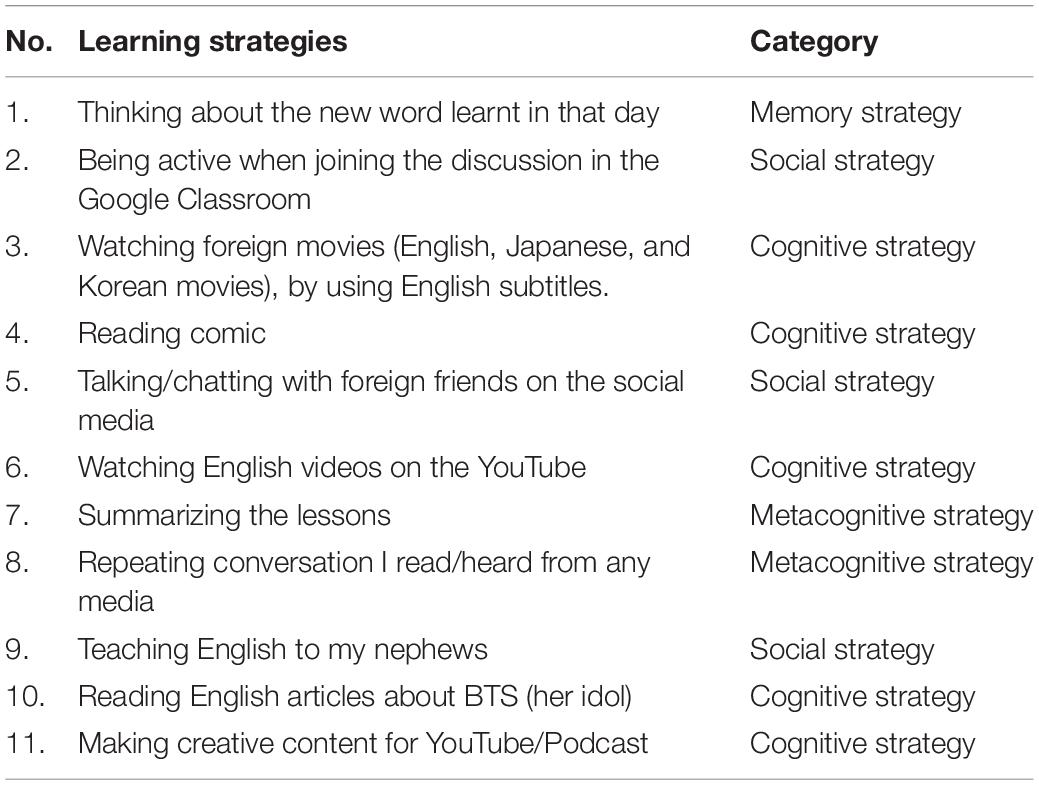

In addition to close-ended items, the questionnaire also had one open question so the participants could list strategies they thought were not listed. Table 3 shows the complete list of those strategies.

Specific strategies mentioned in Table 2 also belongs to those six categories of language learning strategies. When the student said that they thought about the new word learnt that day, they attempted to remember it. This strategy then could be added to the memory strategies. Another example is strategy number two, in which the students were active in the discussion forum. This strategy belongs to social strategy because the students engage in a virtual discussion to use English.

Research Question #2

This research question was answered based on the interview with the students. Some of the participants reported that they did not change their learning strategies during then COVID-19. They only made some adaptations due to the social distance regulation. The interview data revealed that most students still communicate with their friends through social media, such as WhatsApp or Telegram group. This data can be drawn from these interview excerpts:

We have our class WhatsApp group. When I did not understand the materials, I can post questions there. Some of my friends will explain to me or, sometimes, give links for resources (Ari, Interview data, Excerpt #1).

No, I did not frequently ask my lecturer. I prefer to ask my friends; except I need to do so (Ari, Interview data, Excerpt #2).

Next, the changes made by the students are the time allotment for surfing on the internet and the choice of media for learning. Adi, for example, was used to learning online by browsing some materials on the internet, but he browsed more frequently during the COVID-19. It also happened to Tania, who preferred to learn through YouTube. This result supports the data from the questionnaire regarding why social strategies still become favorites for those students. Tania’s answer is presented in the following excerpt.

“Before COVID-19, I also watch YouTube, but more for entertainment. Now, I watch YouTube more for study because I think, sometimes, the lecturer explanation in the Google Classroom was not really clear. I need more explanation and YouTube helped me. I prefer to watch the video explanation instead of reading from a web page” (Tania, Interview data, Excerpt #3).

Adi’s and Tania’s answers reflect that their adaptation to learning strategies did not significantly change during the COVID-19. They only added more time to surf the internet. Padli also experiences this kind of adaptation. His hobby was reading comics, so he had more time to read English comics at home. He said that he enjoyed this activity because it was fun and gave benefits for his English development.

However, some students found a new strategy for learning English. Since students were at home during the pandemic, Alia used this opportunity to teach English to her nephews, improving her English. She introduced new vocabulary to them and explained to them how to use it. When her nephews came to her house, she would invite them to learn English. Aisya also stated that COVID-19 had a positive impact on her learning. Her answer was portrayed in the following excerpt.

“Hmmm…. I don’t know what to say, but I think COVID-19 has a positive effect on me. I have more time to make creative content. So, I like to make content for my podcast/YouTube. However, when we had regular classes, I did not have time to do such activities because I need to attend classes/to discuss group works with my friends. Now, because all the classes are online, I had time to plan and make the content. The content is in English so it also helps me to learn” (Aisya, Interview data, Excerpt #4).

Those participants answer showcase that the pandemic situation brought a positive side for them. In Aisya’s case, she could make creative content as well as learn English. Another positive effect of study from home is the growth of students’ autonomous learning, as expressed by Maya in the following excerpt:

“During the pandemic, I frequently used search engines, such as Google, to look for learning resources. I also like to get more explanations from videos, such as YouTube. When I found important information, I will take notes so I can use it for completing my assignment, or for preparing middle and final tests” (Maya, Interview data, Excerpt #5).

However, it cannot be neglected that some of the participants also complained about the disadvantages of the present emergency remote learning. Unstable internet connection lacks support from family and institutions, and lack of social interaction are some to problems to mention. Ihsan for example stated his problem in the following excerpt.

“I think sometimes it is hard to learn online, especially the connection in my village is not really good. When the lecturer told us to have a Google Meet or Zoom meeting, for example, I need to search for a place with a good signal. It is also frequent that the lecturers voice is unclear or like buffering. This situation, sometimes, made me difficult to understand the lesson” (Ihsan, Interview data, Excerpt #6).

Meanwhile, Meila who had problem related to family support said that when studying from home, sometimes, her family asked her to do household chores. She mentioned that she got more assignments during the online learning, but she also needed to help her parents at home. This situation was different when she studied at campus. She lived in a rent house so no one would bother her when she completing the assignments. Related to the social interaction, some students said that the regulation to keep physical distancing hinder them to have a meeting or a face-to-face discussion. In addition, since many of them were sent to their home they could not meet or do group works after the class.

Discussion

The result shows that social and metacognitive strategies are more favorable for most of the students. In contrast with Supiani et al.’s (2020) study, the social restriction during the pandemic hindered students from social interaction. This condition can be driven by the research context and participants’ factors. In Supiani et al.’s (2020) study, the participants are graduate students with higher perceived isolation levels both socially and academically (Erichsen and Bolliger, 2011). This condition is driven by their need to focus more on their study and projects. Some of the participants said, during the interview, that before the pandemic they used to discuss in groups and doing group work projects. Therefore, although they cannot meet each other, they still keep in touch through social media.

Interview excerpt #1 informed us those students used social media to communicate to help them learn. Djamdjuri and Kamilah (2020) reported that social media, including WhatsApp, is more efficient than the learning management system (LMS). They argued that most of the students had well understood how to use social media, so they did not require much training, and it also consumed less internet data. These advantages facilitate the students to maintain communication, although they could not have a face-to-face discussion.

The last excerpt (#2) implied that the only social interaction that reduces during the remote learning is the students’ communication with the lecturer. In Asian countries context, including Indonesia, this condition is driven by cultural factors. Indonesia holds collectivist culture with high power distance. It makes the teaching and learning usually will be more teacher-centered in which the students are expected to respect teachers (Raymond and Choon, 2017). As a result, it is frequent that students will avoid having direct and frequent communication with their teacher. In Ari’s story, he said he would ask his lecturer when he needed to do it, for example, if none of his friends could answer his questions.

The following strategy used by the majority of the students is cognitive strategies. They covered reasoning, analysis, and concluding. Cognitive strategies help the students manipulate the target language or task correctly by using all their processes (Oxford, 1990). For example, the use of drills to practice the language and a dictionary to find difficult words. Writing meaningful information becomes the most used of the student by 93.8%, using background knowledge to learn information at 87.5%, keep practising 71.9%, and the translating is a strategy that is a little use by students at the percentage 70.3%.

As expressed in Excerpt #5, writing essential information strategies helps the student grow her autonomous learning. Lamb (2004) mentions that learners must be active in learning to learn the language successfully. He said that independent learning is required to make students successful language learners in a collectivist or individualist society. However, the challenge in the collectivist culture is the students are more dependent. They rely on the teacher to guide them in learning (Raymond and Choon, 2017). Since the students learning in isolation during the COVID-19, it forces them to be more independent like what Maya had experienced.

Other two strategies whose high percentage are affective strategies and metacognitive strategies. Affective strategies focus on controlling the emotions, attitudes, motivations and values (Oxford, 1990). These strategies have a powerful influence on language learning because they allow the students to manage their feelings. For example, students may use laughter to relax and praise to reward themselves for their achievements. The strategy most used by the students in affective strategies were listening to the music while learning at 79%, then giving positive encouragement to themselves 71%, and appreciating their works 69.4%. During the interview, some participants said that listening to music made them feel relaxed, which helped them to grasp the information being learnt.

Metacognitive strategies are used by the students to coordinate the learning process by centring, to arrange, planning, and evaluating. These strategies will help the learner to control their own learning. For example, organizing, focusing, and evaluating one’s own learning. In the previous research (Chuin and Kaur, 2015), metacognitive strategies are the most dominant strategies employed by the students. However, in the present study, it is in the fourth rank. Nevertheless, the means the percentage of students using these strategies can be categorized as high (70.7%). Examples of strategies applied were doing self-evaluation at 71.9%, searching how to learn a language at 71.9%, and finding and understanding the main ideas of a text 68.8%.

The students employ compensation strategies to overcome the missing knowledge in the target language due to a lack of vocabulary. The techniques help to allow the students to use the language to speak and write in the target language even when their vocabulary is limited. For example, using linguistic clues to guess the meanings or inventing words to the use of linguistic clues to think compensates their lack of vocabulary. In this concern, most of the students used synonyms and antonyms with a percentage of 65.6%, while using linguistics context to guess the meaning of the unknown word only 51%. The following list is compensation strategies.

Finally, the least strategies are memory strategies. Most of the students use new vocabulary in context strategies with the percentage 70.3% while using keywords to understand a written or spoken text at 41.6% and using physical responses in learning a language at 51.6%. According to Oxford (1990), memorization is a technique that helps students remember more effectively, retrieve, and transfer information needed in the future. Moreover, these strategies will help the students to get the information back.

Regarding the students’ adaptation, it is found that the pandemic did not change their learning strategies a lot. It brings both positive and negative contributions to their learning. The positive effects are the increasing of students’ creativity and autonomy. Aisya’s story reveals that she could make creative content during the study from home because she had more time. It is due to the flexibility of online learning, which allows the students to learn anytime and anywhere (Adedoyin and Soykan, 2020), so the students can manage their time to do other activities. The growth of students’ autonomy in learning can be investigated from Maya’s narration. She becomes more autonomous because of her need to study. Cirocki et al. (2019) argue that Indonesian students had low motivation in learning English, so they did not become familiar with the concept of autonomous learning. The present finding pinpoints that this conclusion will be different when the students are in a certain condition. When the condition required them to be more independent, the students can be more autonomous in learning.

Some challenges that can negatively impact students learning are an unstable internet connection, lack of support from family and institution, and lack of social interaction. To deal with these barriers, the students need to manage their strategies carefully. According to Dhawan (2020), students are required to adapt to those challenges as quickly as possible to survive in the learning environment. Rahiem (2021) also suggests that students remain motivated despite all the limitations they may encounter during the pandemic. The motivation to continuously learn during the pandemic should come from the students themselves by having self-determination, setting their goals, and religious devotion. She also emphasizes the importance of school, friends, and family support to maintain the students’ enthusiasm for learning.

Dealing with those challenges also require lecturers in higher education to be more creative in designing their online classes. During the emergency remote learning, to avoid the absence of social interaction, lecturers can set discussion in the e-learning. They also could assign project-based learning which will require students to be more independent, but still work collaboratively. Ideas for video-making activities for example (see Asfihana and Yansyah, 2022) can be an alternative to mold students’ creativity. As stated by Aisya (Exceprt #4), making video content was one of her interests so it should be taken as an opportunity by the lecturers to assign this kind of engaging activities. The use of video-making activities also can grow students understanding toward better understanding of how to combine between technology and pedagogy in teaching.

Furthermore, Education 4.0 also can be considered to be a method in learning during the uncertainty times. Education 4.0 offers autonomy as well as flexibility. This method suitably match with the technology-based strategies (Srivani et al., 2022a). A research conducted by Srivani et al. (2022b) conclude that the use of Education 4.0 promotes innovation as well as facilitate the learners to have self-learning opportunities. Thus, it is encouraged for lecturers to be update with recent educational technology that can help their students maximize learning either through synchronous or asynchronous ways.

Last, regarding the students’ internal factors such as self-determination, time management, and religious devotion should also be considered in helping them to be well adapted with the new learning mode. Rahiem (2021) mentions that students self-determination can be built by asking them to be more responsible for fulfilling their tasks. They should create challenges for themselves by setting their daily, weekly, or monthly goals so they it will help them to manage their time during the study at home. Rahiem (2021) emphasized on the importance of assignments as a means for facilitating the students to be more organized in learning. However, too many assignments are also not good for students well-being because it can increase their level of stress (Nurwulan et al., 2021). Regarding religious devotion, for muslim students, they can be remained that learning is a responsibility. Teachers can encourage the students to keep studying, even in the emergency remote learning condition, as an expression of being grateful to the God. Rahiem (2021) in his study reported that by having such faith, students remained motivated for they knew that their chance to continue their study in higher education was God’s grace which should be appreciated.

Concluding Remarks

The present research pinpoints that most of the six strategies are used by undergraduate students. Social and cognitive strategies have become the most popular among others. The collectivist culture of Indonesian people where they tend to maintain social harmony (Rajiani and Kot, 2020) supports the popularity of social strategies. Compared to western culture, Li (2019) who investigated the relationship between learners’ demographic and their learning strategy found out that Latin America preferred learning in a quiet and comfortable place, with few distractions to study. The social and physical restrictions did not hinder the students’ interaction from supporting their learning. Social media becomes an alternative to substitute face-to-face discussion with their friends. The COVID-19 pandemic also changes the way students learning. Some students become more creative and autonomous because of the condition allow and require them to do so.

Meanwhile, some barriers such as unstable internet connection, lack of support from family and institution, and lack of social interaction should get attention and solution to minimize the negative impacts of learning in isolation. The students should be more encouraged to manage their time well. Motivating students to have self-determination, religious devotion, and social support are suggestions to deal with those problems.

It implies that the use of social media for accompanying LMS or online classrooms, which are commonly used during emergency remote learning, is highly recommended. Nowadays, almost everyone has social media, such as WhatsApp or Telegram, so it does not require them to train to use its features. The use of social media can help teachers to provide social aspect learning in the online environment. Therefore, teachers are encouraged to include social aspects and interact more with students in the online environment through social media.

Another implication from the present study is the urgency to provide additional resources such as links for online materials. Many of the participants used cognitive strategies. Although the students become more autonomous in learning, supplementary materials from the teachers or lecturers will help them save time for keeping practice and writing notes. They also will get more reliable resources for learning since the internet is like a jungle that contains a lot of information. Besides, training them to choose good and reliable resources on the internet also can be an alternative to solve this problem.

Next, the outbreak of COVID-19 has brought both positive and negative impacts on learners learning strategies. It can be identified that those who previously use social strategies make the biggest changes in their learning strategies. Therefore, it is suggested to maintain the students’ motivation in learning by facilitating them to set their goals during the study from home. Teachers or lecturers are also suggested to continuously give feedback on their learning so they would feel that they get support during learning. Group work and collaboration through certain apps are recommended because friends’ support also matters. Last, support from family is also expected so the students can survive and adapt to this sudden transformation of learning.

This study has limitations, including the coverage of the participants, which only covers two classes in a foreign language setting. More participants with various backgrounds may provide better information about students’ learning strategies. This study also relies on the data based on the students’ information from the questionnaire and interview. Future studies are expected to explore this topic with various research instruments so that the data gathered will be more comprehensive. In addition, using other research designs may provide different perspectives and insights. Last, in the present research the researchers did not measures the benefits or drawbacks of remote learning on students with different learning outcomes, future studies can fill this gap for a better understanding of students’ learning strategies adaptation.

Data Availability Statement

The original contributions presented in the study are included in the article/supplementary material, further inquiries can be directed to the corresponding author.

Ethics Statement

The studies involving human participants were reviewed and approved by the Universitas Islam Negeri Antasari. The patients/participants provided their written informed consent to participate in this study. Written informed consent was obtained from the individual(s) for the publication of any potentially identifiable images or data included in this article.

Author Contributions

NM: conceptualization, design, analysis, drafting manuscript, and final approval. Yansyah: data acquisition, writing, editing, and reviewing. Jumadi: editing and reviewing. All authors contributed to the article and approved the submitted version.

Conflict of Interest

The authors declare that the research was conducted in the absence of any commercial or financial relationships that could be construed as a potential conflict of interest.

Publisher’s Note

All claims expressed in this article are solely those of the authors and do not necessarily represent those of their affiliated organizations, or those of the publisher, the editors and the reviewers. Any product that may be evaluated in this article, or claim that may be made by its manufacturer, is not guaranteed or endorsed by the publisher.

References

Adedoyin, O. B., and Soykan, E. (2020). Covid-19 pandemic and online learning: the challenges and opportunities. Interact. Learn. Environ. doi: 10.1080/10494820.2020.1813180

Aktaş, M. (2012). Cultural values and learning styles: a theoretical framework and implications for management development. Procedia Soc. Behav. Sci. 41, 357–362. doi: 10.1016/j.sbspro.2012.04.041

Alfian, A. (2018). Proficiency level and language learning strategy choice of islamic university learners in Indonesia. TEFLIN J. 29, 1–18. doi: 10.15639/teflinjournal.v29i1/1-18

Amir, L. R., Tanti, I., Maharani, D. A., Wimardhani, Y. S., Julia, V., Sulijaya, B., et al. (2020). Student perspective of classroom and distance learning during COVID-19 pandemic in the undergraduate dental study program Universitas Indonesia. BMC Med. Educ. 20:392. doi: 10.1186/s12909-020-02312-0

Asfihana, R., and Yansyah. (2022). Integrating technological pedagogical content knowledge into video-making activities: learning from practice. J. Asia TEFL 19, 345–353.

Bryson, J. R., and Andres, L. (2020). Covid-19 and rapid adoption and improvisation of online teaching: curating resources for extensive versus intensive online learning experiences. J. Geogr High. Educ. 44, 1–16. doi: 10.1080/03098265.2020.1807478

Carrillo, C., and Flores, M. A. (2020). COVID-19 and teacher education: a literature review of online teaching and learning practices. Eur. J. Teach. Educ. 43, 466–487. doi: 10.1080/02619768.2020.1821184

Chamot, A. (2004). Issues in language learning strategy research and teaching. Electron. J. Foreign Lang. Teach. 1, 14–26.

Chang, C. H., and Liu, H. J. (2013). Language learning strategy use and language learning motivation of Taiwanese EFL university students. Electron. J. Foreign Lang. Teach. 10, 196–209.

Chuin, T. K., and Kaur, S. (2015). Types of language learning strategies used by tertiary English majors. TEFLIN J. 26:17. doi: 10.15639/teflinjournal.v26i1/17-35

Cirocki, A., Anam, S., and Retnaningdyah, P. (2019). Readiness for autonomy in English language learning: the case of Indonesian high school students. Iran. J. Lang. Teach. Res. 7, 1–18.

Demuyakor, J. (2020). Coronavirus (COVID-19) and online learning in higher institutions of education: a survey of the perceptions of Ghanaian international students in China. Online J. Commun. Media Technol. 10:e202018. doi: 10.29333/ojcmt/8286

Dhawan, S. (2020). Online learning: a panacea in the time of COVID-19 crisis. J. Educ. Technol. Syst. 49, 5–22. doi: 10.1007/s11159-021-09889-8

Djamdjuri, D. S., and Kamilah, A. (2020). WhatsApp media in online learning during COVID-19 Pandemic. Engl. J. 14, 69–74. doi: 10.32832/english.v14i2.3792

Erichsen, E. A., and Bolliger, D. U. (2011). Towards understanding international graduate student isolation in traditional and online environments. Educ. Technol. Res. Dev. 59, 309–326. doi: 10.1007/s11423-010-9161-6

Fatimah, F., Rajiani, S. I., and Abbas, E. W. (2021). Cultural and individual characteristics in adopting computer-supported collaborative learning during covid-19 outbreak: willingness or obligatory to accept technology? Manage. Sci. Lett. 11, 373–378. doi: 10.5267/j.msl.2020.9.032

Huang, S. C. (2018). Language learning strategies in context. Lang. Learn. J. 46, 647–659. doi: 10.1080/09571736.2016.1186723

Hurd, S. (2006). Towards a better understanding of the dynamic role of the distance language learner: learner perceptions of personality, motivation, roles, and approaches. Distance Educ. 27, 303–329. doi: 10.1080/01587910600940406

Lamb, M. (2004). “It depends on the students themselves”: independent language learning at an Indonesian state school. Lang. Cult. Curric. 17, 229–245. doi: 10.1080/07908310408666695

Li, K. (2019). MOOC learners’ demographics, self-regulated learning strategy, perceived learning and satisfaction: a structural equation modeling approach. Comput. Educ. 132, 16–30. doi: 10.1016/j.compedu.2019.01.003

Li, L. N., and Wang, X. (2015). Culture, language, and knowledge: cultural learning styles for international students learning Chinese in China. US China Educ. Rev. A 5, 487–499. doi: 10.17265/2161-623x/2015.07a.004

Morgan, H. (2020). Best practices for implementing remote learning during a pandemic. Clearing House 93, 135–141. doi: 10.1080/00098655.2020.1751480

Nurwulan, N. R., Kurniawan, B. A., Rahmasari, D. A., Rahmasanti, J. W., Abbas, N. A., and Hadyanto, M. H. (2021). Students workload and stress level during COVID-19 pandemic. Indones. J. Educ. Stud. 24, 9–16.

Oxford, R. L. (1990). Language Learning Strategies: What Every Teacher Should Know. Boston, MA: Heinle and Heinle.

Pokhrel, S., and Chhetri, R. (2021). A Literature review on impact of COVID-19 pandemic on teaching and learning. High. Educ. Future 8, 133–141. doi: 10.1177/2347631120983481

Rahiem, M. D. H. (2021). Remaining motivated despite the limitations: University students’ learning propensity during the COVID-19 pandemic. Children Youth Serv. Rev. 120:105802. doi: 10.1016/j.childyouth.2020.105802

Rajiani, I., and Kot, S. (2020). Javanese Indonesia: Human resource management issues in a uniquely collectivist culture. Cult. Manage. 4, 9–21. doi: 10.30819/cmse.4-2.01

Raymond, C. Y., and Choon, T. (2017). Understanding Asian students learning styles, cultural influence and learning strategies. J. Educ. Soc. Policy 7, 194–210.

Rustam, N. S., Hamra, A., and Weda, S. (2016). The language learning strategies used by students of merchant marine studies polytechnics makassar. ELT Worldw. 2:77. doi: 10.26858/eltww.v2i2.1689

Saks, K.Leijen, Ä. (2018). Adapting the SILL to measure Estonian learners’ language learning strategies: the development of an alternative model. Lang. Learn. J. 46, 634–646. doi: 10.1080/09571736.2016.1191169

Sepulveda-Escobar, P., and Morrison, A. (2020). Online teaching placement during the COVID-19 pandemic in Chile: challenges and opportunities. Eur. J. Teach. Educ. 43, 587–607. doi: 10.1080/02619768.2020.1820981

Srivani, V., Hariharasudan, A., Nawaz, N., and Ratajczak, S. (2022a). Impact of Education 4.0 among engineering students for learning English language. PLoS One 17:e0261717. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0261717

Srivani, V., Hariharasudan, A., and Pandeeswari, D. (2022b). English language learning using education 4.0 in Karimnagar, India. World J. Engl. Lang. 12:325. doi: 10.5430/wjel.v12n2p325

Supiani, Rafidayah, D., and Yansyah, and Nadia, H. (2020). The emotional experiences of Indonesian PhD students studying in Australia during the COVID-19 pandemic. J. Int. Stud. 10, 108–125. doi: 10.32674/jis.v10is3.3202

Tanjung, F. Z. (2018). Language learning strategies in English as a foreign language classroom in Indonesia higher education context. LLT J. 21, 50–68. doi: 10.24071/llt.2018.suppl2106

The Jakarta Post (2020a). War Begins on Coronavirus. Editorial Board. Available online at: https://www.thejakartapost.com/academia/2020/03/03/war-begins-on-coronavirus.html (accessed August 5, 2021).

The Jakarta Post (2020b). Challenges of Home Learning During a Pandemic Through the Eyes of a Student. Lifestyle. Available online at: https://www.thejakartapost.com/life/2020/04/11/challenges-of-home-learning-during-a-pandemic-through-the-eyes-of-a-student.html (accessed August 5, 2021).

Keywords: exploratory study, learning strategies, online learning, EFL, emergency remote learning

Citation: Mufidah N, Yansyah and Jumadi (2022) Survival Foreign Language Acquisition Strategies During the Emergency Remote Learning: An Exploratory Study in Molding Indonesian Students’ Creativity. Front. Educ. 7:901282. doi: 10.3389/feduc.2022.901282

Received: 21 March 2022; Accepted: 26 April 2022;

Published: 26 May 2022.

Edited by:

Yanki Hartijasti, University of Indonesia, IndonesiaReviewed by:

Yudhi Arifani, Universitas Muhammadiyah Gresik, IndonesiaA. Hariharasudan, Kalasalingam University, India

Copyright © 2022 Mufidah, Yansyah and Jumadi. This is an open-access article distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution License (CC BY). The use, distribution or reproduction in other forums is permitted, provided the original author(s) and the copyright owner(s) are credited and that the original publication in this journal is cited, in accordance with accepted academic practice. No use, distribution or reproduction is permitted which does not comply with these terms.

*Correspondence: Nida Mufidah, nidamufidah@uin-antasari.ac.id

Nida Mufidah

Nida Mufidah Yansyah

Yansyah Jumadi

Jumadi