Changes in teaching from the perspective of novice and retired teachers: Present and past in review

- Department of Didactics and School Organization, University of Murcia, Murcia, Spain

Background: This study aimed to understand the perceptions that Spanish teachers of different educational levels have about the functions attributed to them, the overload of administrative tasks that they face daily, and the external consideration that their professional profile has raised. A generational perspective was adopted in this study, taking into consideration different educational stages: Early Childhood, Primary, and Secondary Education.

Methods: This descriptive study was developed using a qualitative methodology. The data were extracted through semi-structured interviews with 60 Spanish teachers from public schools. The information was analyzed with the qualitative data analysis tool ATLAS.ti, version 22.

Results: The results extracted from this study expose the overload of administrative work that teachers face daily, preventing them from developing pedagogical tasks that can improve their practice. In addition, the results highlight that a series of prejudices and negative external considerations toward the figure of the teacher are developing in the society.

Conclusion: It can be concluded that older and more experienced teachers in educational centers place more emphasis on the work overload that they have assumed over the years in their work. However, novice teachers do not show as much concern about this work overload. Additionally, teachers state that the society has a negative regard for their work.

1. Introduction

Traditionally, education has depended on the family and school (Prieto, 2008). In this article, the formative function of schools is analyzed through the figure of the teacher, as an essential part in the education of the student body. To this end, we first present the legislative and additional functions attributed to the teachers. This helps build clarity about the tasks assigned to teachers and what factors determine whether or not they can be carried out.

We then analyze the factors that have contributed to the deterioration of the teaching profession in the last decade. More specifically, teachers’ decision-making capacities have been gradually limited, by not consulting them when making far-reaching decisions affecting them and implementing such decisions. Currently, we are experiencing education policies that are committed to uniformity, standardization, and accountability, which are leading the teaching practice toward bureaucratization (Sanz Ponce et al., 2020), which is distant from the teacher’s passion for teaching (Day, 2006). These and other factors distort the functions of the teacher and the perception that the society has of them. According to Avalos et al. (2010), the ways in which teachers are perceived and valued socially influence the ways in which they see themselves and perform their role.

In this sense, the objective of this article is to present the perceptions that teachers have about their teaching work and the workload they assume. It is also intended to expose the perceptions they have about their consideration and social value. In short, the study this article reports aimed to analyze the situation that teachers are experiencing based on their perceptions. To this end, we consider their different professional experiences, analyzing the factors that are conditioning their teaching practice.

There is no doubt that the teacher is a fundamental part of the teaching–learning process that takes place in the classroom, having a significant impact on the quality of the educational system (Barber and Mourshed, 2008; Hattie, 2017; Sanz Ponce et al., 2020). In this regard, Avalos et al. (2010) stated that “the success of educational systems and student learning depends on the quality of teachers (…) and how this is combined with social expectations regarding their role” (p. 243). Likewise, Colomo and Aguilar (2019) recognized that teachers “have a responsibility and commitment to improve society” (p. 10). These same authors state that there is currently concern about the role of the teachers in the society and what skills they should have, taking into account our educational reality.

In recent decades, the demands of the teaching profession have been progressively increasing, including not only the mastery of new methodologies and the integration of new technological tools, but also attitudes and ethical commitments, the competence to create and sustain personalized learning relationships, willingness and skills to work in coordination with different professionals, resolve to fight against any inequality, and contributing to social justice (Escudero, 2011).

Today, a teacher is allocated and delegated functions that were previously only assigned to the family nucleus. They are entrusted with the tasks of educating, mediating in cases of conflict, and acting as a link between the family and center, instructor, etc. (Pérez and Rodríguez, 2013). In addition, they must carry out other tasks, such as the preparation of class material, undertaking professional training, innovation, coordination, work and involvement in the center, completing paperwork, etc. These tasks sometimes result in their not having sufficient time to reflect on their teaching practice and often generates discomfort in the assessment of the set of tasks they must perform and the need to redefine their teaching role (Guzmán and Javier, 2020; Merieu, 2020).

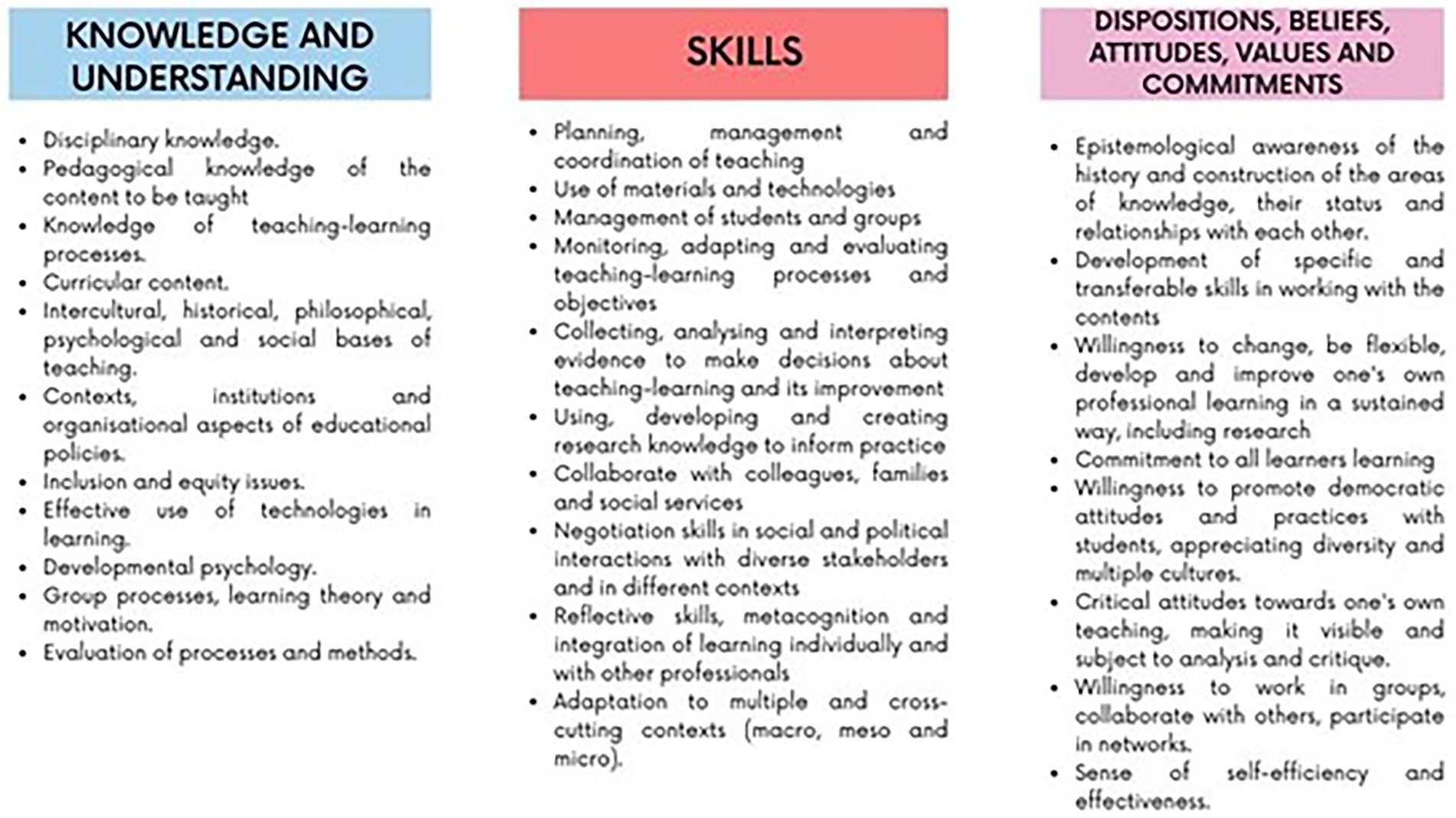

The conditions of the teaching practice have changed at a significant speed (see Figure 1); thus, teachers have had to adapt to the changes and continue to develop the functions assigned to them according to the legislation in force in each country. However, despite the effort that teachers make (resulting in overexertion on many occasions), a series of prejudices are created around them, meaning that they are not always valued as they should be by society (Vílchez and Fernando, 2019; Camacho, 2020).

Figure 1. Key competencies for educators. Source: EU (2013, p. 45–46).

García et al. (1991) enumerate a series of issues that have been generalized about the teaching practice and frequently detract from the teachers’ role. There is a growing tendency to generalize the defects or negative characteristics of some teachers to the rest of the teaching body, such as lack of punctuality, motivation, and training, disinterest, and apathy. In this sense, it should be noted that the figure of the teacher is usually questioned. This results in a negative external reputation due to a decrease in the level of trust toward their work, as well as a loss of respect and lack of consideration, which contribute to the creation of a tense atmosphere between the family and educational center, as teachers become scapegoats for the school’s failure. These aspects, along with others, such as the exhaustion and fatigue caused by professional overload, can lead to burnout syndrome, which is quite common among teachers.

Society currently demands “full professionalism from those who are dedicated to this activity” (Gonzalvez Perez, 2016, p. 199); that is, teachers are required to devote themselves to their profession without considering the emotional or affective aspects of it, or the (administrative) workload they face every day. Currently, we are facing a bureaucratized vision of the profession. In 2012, Bolívar remarked that “external changes and regulations (…) have led teaching practices (…) to increasingly bureaucratized tasks. In the same way, Hargreaves (2003), as cited in Tardif (2010) stated that the teaching field is becoming bureaucratized, subtracting time from the preparation of the teaching–learning process and reducing it to a mere execution of marked and predetermined tasks from higher bodies. In contrast, Perrenoud (2012) has stressed the idea that “the school was locked into uniformity” (p. 15), downplaying the role of teachers as drivers of change.

This discourse, however, is not new; almost three decades ago, Zurriaga Llorens (1993) pointed to bureaucratization as an overload of work imposed on the teacher that has a direct impact on the quality of teaching, given that more time is devoted to administrative tasks than to educational tasks. Several studies report (Hargreaves, 1992; Esteve, 2006; Lui and Ramsey, 2008) that teachers emphasize the lack of time to prepare for their classes, attend to their students, prepare materials, and undertake training due (in most cases) to the heavy administrative workload that they must face daily (Bolívar, 2012). This, along with other arguments, can be the cause of the demotivation, fatigue, and pessimism that some teachers experience.

Taking this into account, we can demonstrate that both external consideration and bureaucratization are aspects that can affect the adequate performance of the teaching role, and that these factors often go hand in hand. Day (2011) recognized that the erosion of teachers’ morale is associated with misconceptions about their role and the work overload that administrations and centers demand from them that results in less time to delve into their work and prepare for it.

Given this situation, Bolívar (2012) recognized that the best antidote to bureaucratization was teacher professionalization. For their part, Day (2011) stated that, for teachers to demonstrate commitment, they must be in “less alienating environments, with less bureaucratic management that is not only based on performative measures” (p. 219). In short, given the external consideration of their work and the overload of administrative burden that teachers face regularly, we must promote confidence in their functions, not increase their workload, resort to responsibility and conciliation in order to maintain a suitable atmosphere, provide them with tools to promote quality teaching, and offer them time for training and the preparation of tasks. In the words of Fullan (2002) and Hargreaves and Shirley (2012), we must allow teachers to become “agents of change” through training. Recent studies highlight the impact that both factors (external consideration and overload of administrative tasks) have on the teaching task (Avilés, 2019; Londoña Montoya et al., 2019; Moreno and Yreidys, 2019).

However, there is hardly any research that focuses on knowing how teachers currently live their profession, the social consideration they perceive of their work and the valuation they make of the administrative tasks they must perform. In short, the well-being of teachers in schools is a focus of interest for various international organizations, which have identified it as a priority for research (OECD, 2019, 2022). What do teachers think about this? How do they currently experience their profession and well-being? Do they perceive that their profession has undergone many changes? To answer these questions, teachers of different generations and at different levels of their profession (novice teachers, experts, and retirees from different educational stages) were interviewed to determine their perception, interpretation, and social consideration of their work, as well as the factors that are impacting their teaching practice.

2. Materials and methods

This study is part of a broader project1 that uses a mixed methodology (qualitative and quantitative methods; Portela et al., 2022). For that project, a multiphase design that covers two sequential studies was developed: the first focused on the generational diversity of teachers and the other on intergenerational collaboration among teachers. Both phases incorporate a quantitative and qualitative methodology, which are fundamental aspects in the context of this type of methodology (Creswell, 2015). The project has collected information from both focal groups and utilized semi-structured interviews (Patton, 2015; Stewart and Shamdasani, 2015).

For this article, the information extracted from the first sub-study dedicated to intergenerational diversity among teachers has been used, specifically the data from the interviews. For this reason, only qualitative data will be presented.

2.1. Sample

For the selection of the participants, chain or network sampling (also known as snowball sampling) was carried out: “key participants are identified and added to the sample, they are asked if they know other people who can provide more data or expand the information” (Morgan, 2008, p. 816), and once contacted, these other people are also included. The following criteria were applied for the selection of the participants:

(a) Teachers at different educational levels: Early Childhood Education (Second Cycle), Primary Education, and Secondary Education (including mandatory secondary education and professional training).

(b) Teachers of centers supported with public funds.

(c) New teachers (born after 1990 and with a maximum of 6 years of teaching experience); veteran teachers (teachers more than 50 years of age and with more than 10 years of teaching experience); and retired teachers (forced or voluntary retirement, excluding retirement for disability).

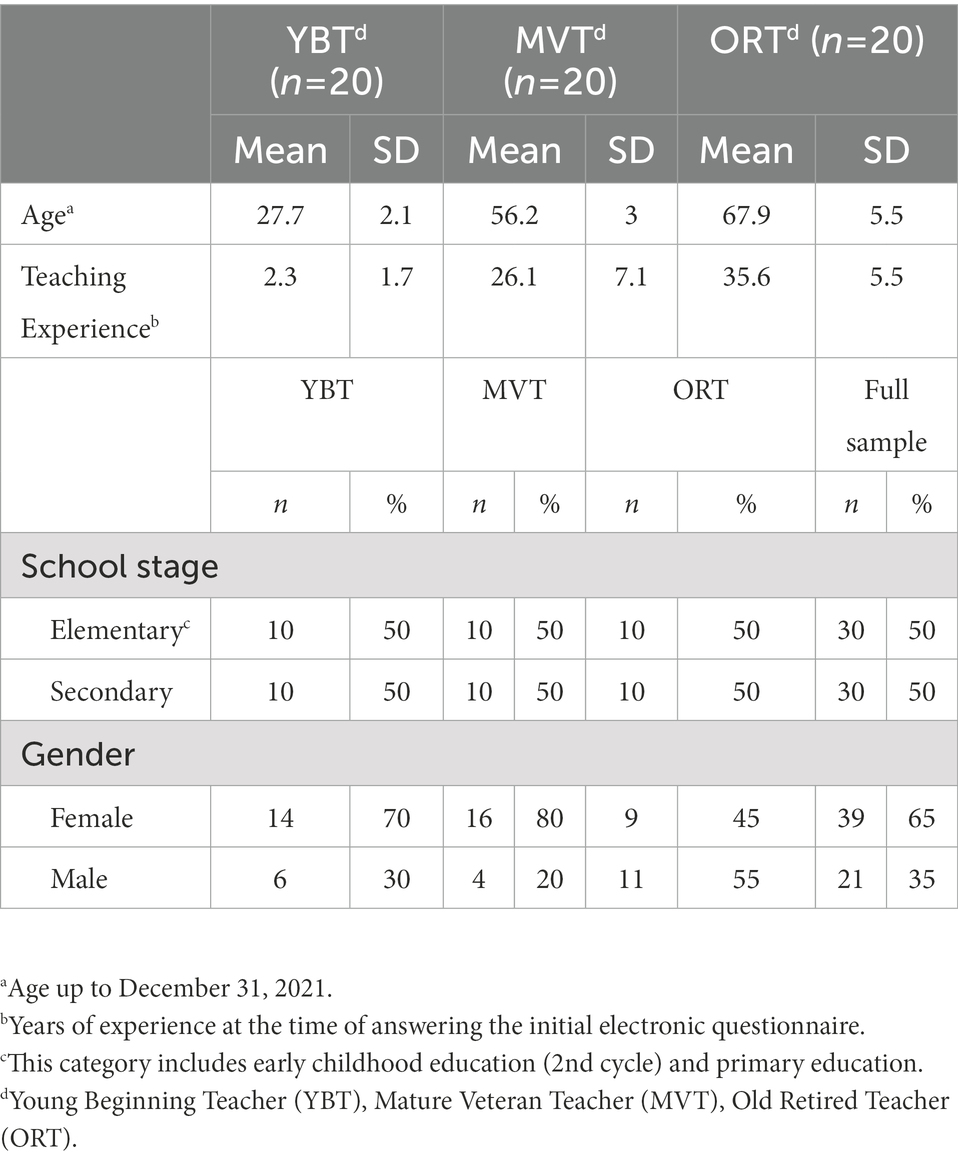

The sample was made as representative as possible of the Spanish territory. Thus, considering the criteria for the selection of the teaching staff, 20 teachers were chosen for each teaching experience and 15 teachers for each educational level. The final sample consisted of 60 teachers from all over the Spanish territory. Participant characteristics are shown in Table 1.

2.2. Data collection

Data for this study were collected through semi-structured interviews. According to Sampieri et al. (2014), this technique is “based on a guided set of questions where the interviewer has the freedom to make additional questions to clarify concepts or obtain more information” (p. 436). These types of interviews allow us to understand the perceptions and beliefs that each participant has of certain aspects (Patton, 2015), while also allowing us to understand emotional experiences (Hargreaves, 2005). The interviews were conducted by referring to the protocol and guidance designed by the project research team. Initially, the interviews were conducted in a pilot test and, after achieving the expected results, the appropriate improvements were made and applied to the rest of the participants.

Four central questions were included in the interview protocol for the first sub-study (intergenerational diversity), which were subdivided into other specific questions in order to delve into the specific topic. For this study, data comprised responses to questions such as: “What is your vision of the teaching profession and the teaching practice, and why do you have this vision?”; “How did you come to see teaching as a profession?”; and “With whom do you share and/or have shared a vision of the teaching profession?”

2.3. Data analysis

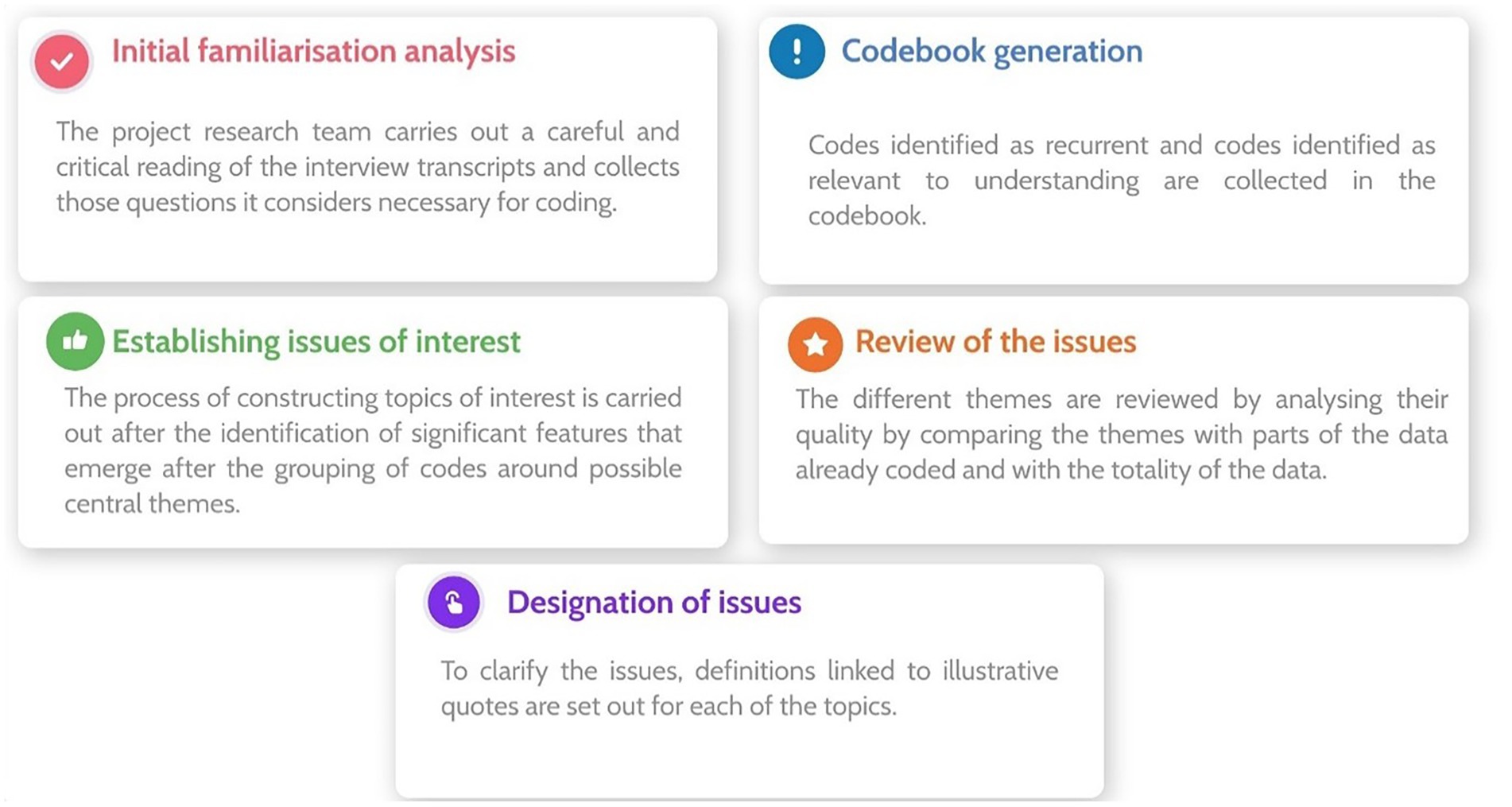

For data analysis, reflective thematic analysis (Braun and Clarke, 2021) and constant comparative analysis (Tracy, 2020), were implemented. The analysis was based on the interpretive conception of the meanings granted to the interviewees’ responses, based on the theoretical orientations of the research team. Therefore, the analysis carried out is of an inductive nature. The data analysis was conducted based on the proposal established by Braun and Clarke (2006), through the phases outlined in Figure 2.

The ATLAS.ti software, version 22, was used for the qualitative analysis of the data. This tool facilitates systematic deepening by the researcher, as well as the presentation of valid and reliable results through analysis techniques that allow the conceptual surface of the data to be transferred (Hwang, 2008; Friese, 2019; Soratto et al., 2020).

2.4. Ethics statement

The research project under which this study was conducted was reviewed and approved by the Research Ethics Committee of the University of Murcia (Approval Identification Code: 2087/2018); this included the information sheet of the participants and the informed consent form to participate in the study. In addition, all members of the sample participated on a voluntary basis. After explaining to them the development of the research and that their participation would be anonymous and confidential, they filled out an electronic form in which they gave their informed consent to participate.

2.5. Research quality

The research developed here followed the criteria of quality and rigor typical of qualitative research. The researchers adopted the principle of trustworthiness and the associated criteria that have brought agreement to the research (credibility, transferability, dependability, and confirmability; Berkovich and Grinshtain, 2021; Yadav, 2021). The most salient strategies for each criterion are outlined below:

• Credibility, increasing the internal validity of the research, using multiple data collection sources in order to triangulate information. Reach a sufficient level of theoretical data saturation. Identify negative or controversial evidence in the re-examination of categories.

• Transferability, the research process has been precisely developed through the various publications and reports. Morevoer, formulating context-relevant working hypotheses that give external validity to the research.

• Dependability, triangulating the data (see Portela et al., 2022) and per-forming data logging using ATLAS.ti software. The systematicity with which the data have been treated, among others, provides consistency to the research.

• Confirmability, by checking the data obtained with the participants themselves and discussing the information with the research group. Thus, the researcher’s perception has been contrasted with the sample components.

3. Results

3.1. General characterization of results on central analysis categories

We will first address a series of general considerations that will help the reader characterize the administrative work carried out by teachers and the external consideration that they present. In this way, a first presentation of results from a macro-level analysis is proposed in order to facilitate the understanding of the established central categories and subsequently develop a detailed analysis.

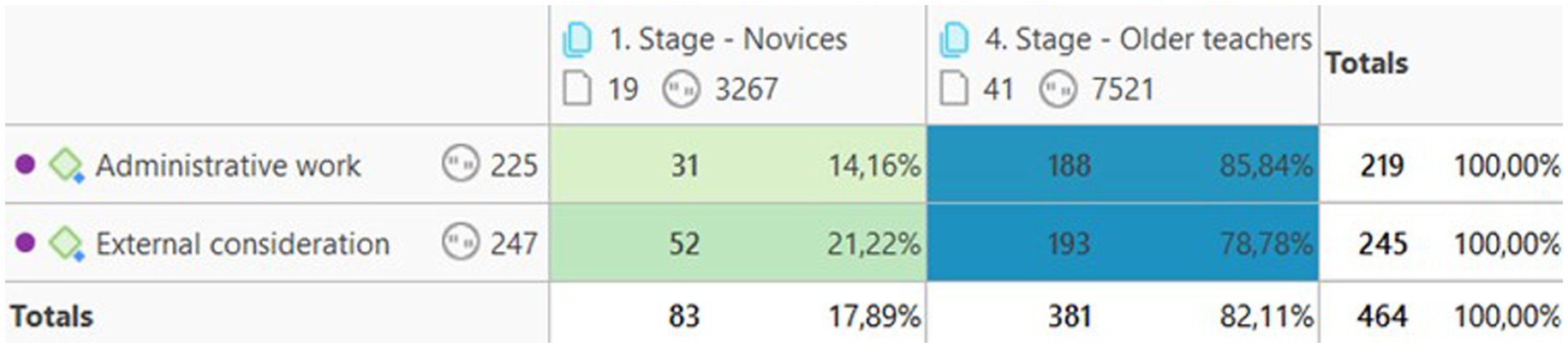

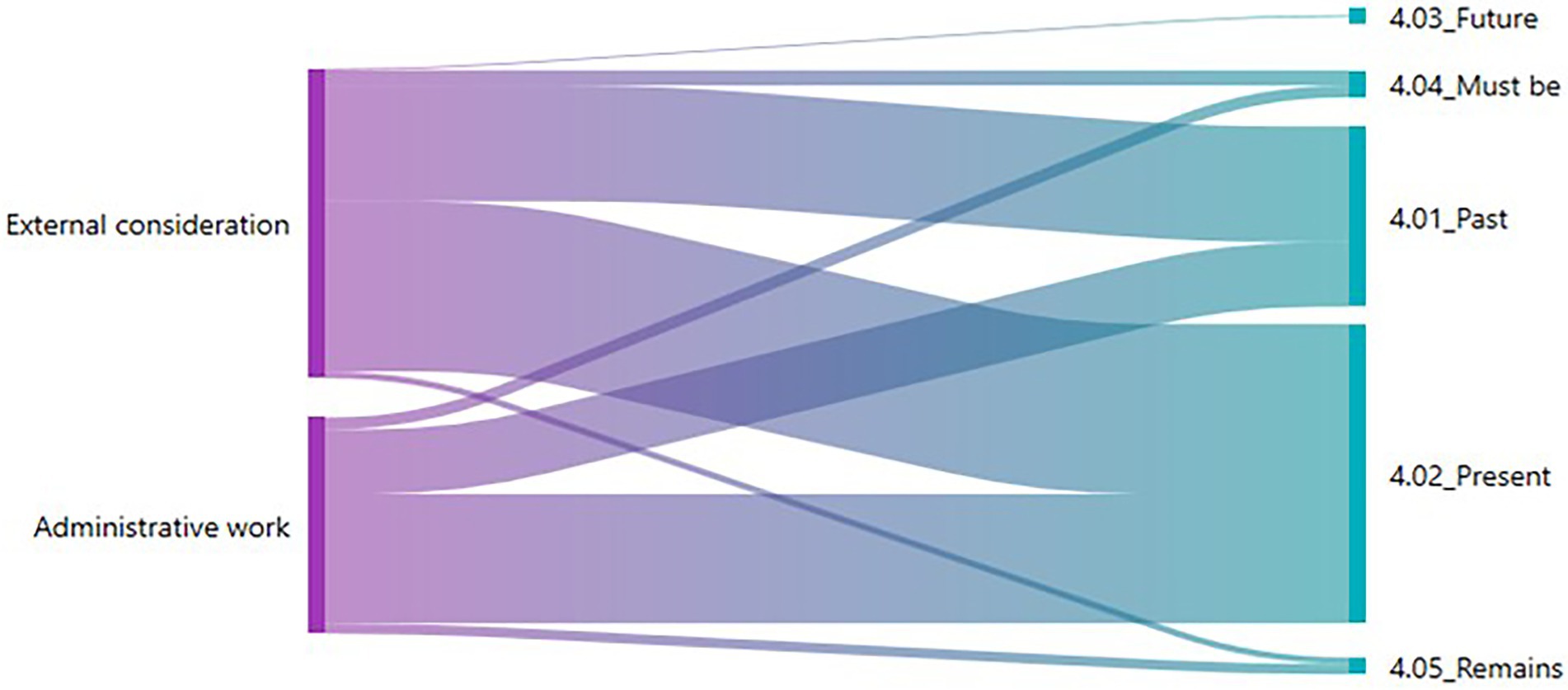

In Figure 3, the relationship between the identified central categories is presented alongside the groups of documents referred to by means of a document-code table. The clear prevalence of these two categories in older teachers can be clearly appreciated (85.84% for administrative work and 78.78% for external consideration) but is far less prevalent in novice teachers.

These results lead us to question why young people have less consideration for those two issues. If we investigate the citations that refer to them, we see that there is no other category to which any of those used in this analysis is robustly linked. Therefore, a conceptual motivation cannot be established. However, it can be noted that this difference is due to a progressive change in the two categories.

In Figure 3, administrative work and external consideration are related to the temporality in which the teachers place each of the citations. The evolution of the citations from the past to the present can be easily appreciated by multiplying the number of mentions of administrative work and external consideration in the present. This shows that these two elements currently deserve greater consideration from older teachers than they did in the past.

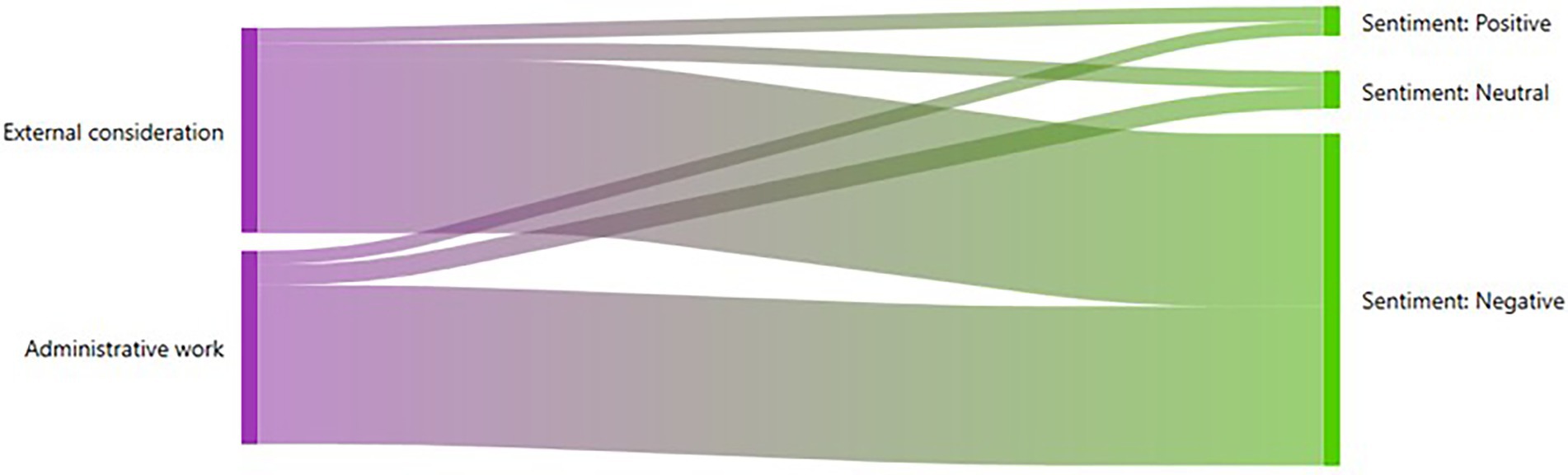

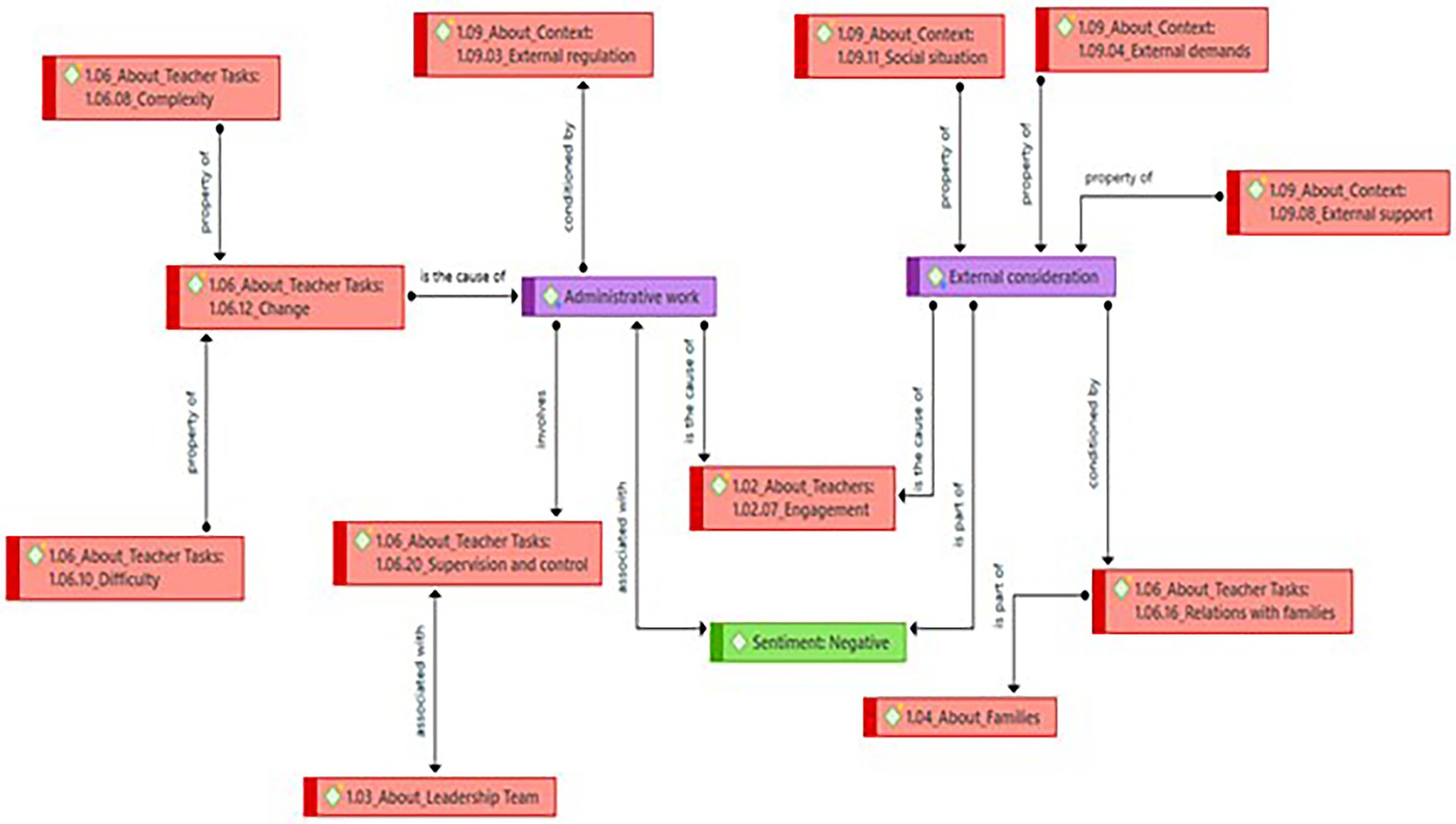

Due to the differences present until now, it is interesting to understand the perception that teachers have about these differences. In order to obtain this data, a sentiment analysis was carried out using ATLAS.ti, which has an algorithm that identifies the emotional effect produced on participants by their discourse. In Figure 4, it can be seen that, in both categories, the prevalence of the discourse is in a negative sphere, so it can be inferred that the progression seen in Figure 5—the increase in the prevalence of the teachers’ discourse on these two issues—currently has a negative emotional effect.

3.2. Delving into the conceptual relationship of administrative work and the external consideration of teachers

Through Figure 6, we can obtain an initial approximation of the content of the discourse. It must be taken into account that, in a preliminary review of the categories that are of interest to us, no relevant link was found with others related categories. Therefore, the suggestions below will be based on the discourse of older teachers.

We can begin to address the discourse content from the change that teachers claim to have experienced in their work and how this change, which is caused by external regulation and the social state of affairs, brings complexity and difficulty, leading to an increase in administrative work. Teachers have a negative perception of these changes because they have considerably increased the bureaucratization of their work and, due to so much “play” with them, their perceived external consideration has decreased. Next, these questions and others that are of interest for the proposed research hypotheses will be developed. These can be evidenced by the following quote:

Obviously, the fundamental part of our profession is teaching, directly teaching students, but there is an arduous and important work behind it, and although some of this directly contributes to the work with the students, other tasks are more bureaucratic, more administrative; but in any case, there is a great task outside the classroom that is unknown and therefore not sufficiently valued (D38:7).

3.2.1. The change in the educational profession and its bureaucratization

Something that has been recurrent in the discourse of the teachers interviewed is the constant reference to different elements of homework and how the administrative work has gradually increased. This implies, on the one hand, an evolution of the teaching profession and, on the other hand, a greater workload for teachers. Among others, they point out the constant task of implementing action protocols that strictly regulate their work, curricular changes at the same pace as government changes, and the implementation of new resources as they appear in society. Thus, issues that were previously sporadic and carried out for necessity are currently being rejected by the teachers:

What we used to do has now been converted into the general norm, organizing school councils is now law; in my school, three parents, three teachers, and three coordinators used to hold meetings […], but this was born out of necessity. We almost started it, and now it has become mandatory. I always say that when something becomes law, it is perverted (D11:8).

All of this evolution experienced by teachers has been a long-distance race in which numerous changes have taken place. However, they have not seen an improvement in their teaching conditions or a decrease in the daily tasks that add complexity to it. The complexity of the teaching tasks has remained constant over the years and has been worsened by legislative changes.

A perspective, although logical, that high school of more than twenty years ago is not the high school of today. But well, I believe that part of the problems, concerns, and challenges of a teacher back then are quite similar to those that exist now (D38:3).

In addition to the aforementioned issues, the different changes in the profession imply greater control and supervision in their daily work. As in any matter derived from an external regulation, its extension is manifested in the monitoring of its compliance by the administrative and management figures of the educational center. Teachers perceive this unjustified need for control as an element of greater pressure in their work because they have always striven to achieve excellence in the teaching–learning process. This new dynamic in the relationship between teachers and management figures has given rise to problems between colleagues, hindering the professional relationships of teachers:

It also depends on who the staff is, but the circumstances give rise to some colleagues exercising an even despotic power. I say it because clearly I have experienced how the situation lends itself to abuses of power, and I have suffered those. […] as it occurs when there is a strong power, in other words, people align with power (67:19).

According to the teaching staff, the external regulation imposed on them is harmful to education itself and hampers their task. Teachers indicate that, with each change that is presented to them, their work increases to the point that, before they are able to implement the change, a new reform arrives that makes them start the process over again. This situation results in an overload of work to the detriment of other tasks directly related to the act of teaching.

… the constant changes to which we are subjected […] weighs heavily on the training of the teaching staff in this country, due to the adapting work involved: teachers changing their methodology, their planning, and even the conceptual, procedural, and attitudinal content. All that change being implemented, and then bang! A change, and then another change of government, resulting in another change (D38:15).

The lack of improvement of the teaching practice, despite the continuous changes, evidences the increase in complexity and bureaucratization of the tasks without any type of alleviation. This situation, in turn, results in complications in the relationships with other agents, such as the families themselves.

… at a certain moment, the administration goes very slowly, and you require the help of another professional. Child psychiatry in the Spanish health system is very poor, because they do not give you appointments […] So, you turn to other professionals and the truth is that they don't even communicate what they've said, they don't tell the truth to the parents either, then the parents confront you and I think: “Jeez! What did I get myself into this mess for?!” And sometimes, you don't want to get involved more than you need to, and you think to yourself, I will pass it, approve it, and let it be what God wants, right? Because in the past, getting involved in that way, well, has led me to many confrontations with families and with other professionals since they do not collaborate with you at all (D66:8).

Hence, the bureaucratization experienced by teachers is immensely linked with their external consideration. The lack of agility to solve problems and the impediments or limitations to carrying out their jobs with greater quality are the main causes for external agents, such as families, negatively perceiving the work they do, as the families are unaware that, in many instances, the teachers are strongly constrained by external regulations.

3.2.2. Lack of external consideration as a consequence of bureaucratization

The social situation and the external demands experienced by teachers are some of the main causes of change in their work, as has already been noted by the changes they have suffered in their role. Any fact of social interest has repercussions in the school system; for instance, the inclusion of new technologies, the different trends that may appear or, as many point out, any negative results in education, will always be attributed to teachers.

From the counseling is the message, that is, if there is an educational failure and the children do not pass, it seems that the problem is ours; "Review the methodology, change I don't know what, change something" (D64:82).

In addition to the overload in the work of teachers caused by the increasing bureaucracy, one needs to consider their function as a “channel” through which the different issues are transferred to the students and their families. They are the intermediaries between the different levels that exercise the external regulation of the teaching practice and the participants whom these regulations affect. Teachers act as informants for families with the consequences derived from the issues that may be questioned.

A center located in a middle-class neighborhood, I tell you, as I had [students from] middle class, upper middle class, who did not have special schooling problems […] this is different from another center in another area of Córdoba, with other students who are from different social backgrounds and that is why each center has to have its autonomy and the parents have to know; the parents have the right to know which center project is going to be applied to their children. This seems fundamental to me and this, I believe, is the great disadvantage that public education has with respect to private education (D7:36).

Thus, families are the main agents from whom teachers receive feedback on their work. To a great extent, it is from the relationship with the families that their perceived external consideration is built. Some of this feedback is related to the feeling that they are not carrying out their work correctly, or that their consideration depends on that of the school itself based on different aspects:

In high school it also happens that there are families demanding things they shouldn’t from teachers (D40:135).

The prestige of the school has a great influence on the assessment and perspectives, on the expectations that parents have (in the case of younger students) and the students themselves (in the case of older students) can have; all this from the rankings (D38:28).

All issues that have been raised, both in the current section and the previous one, are a source of discredit on the part of parents and students and, in the end, the social stigma that teachers suffer and that conditions the way they carry out their work.

It's not that they have to give you prizes, but simply that they don't insult you, that they don't despise your work, that they stop getting involved in what you do since they argue "You don't know"; there are always parents, families, the society that surrounds you telling you “It’s your job,” just like that. The truth is that, lately, more and more people despise the work of the teacher. They don't respect you as a professional, they get involved in your work, they say how you have to do it, and they give you orders: “Hey, don't do that. No, no, no, don't touch, don't say, don't do, don't mess around” (D66:3).

Previously, the strong relationship between the social situation and the external demands of teachers was mentioned, and its direct impact on the teaching practice and indirect impact on the intensity and extension of administrative work carried out by teachers was noted. Furthermore, one of the most significant consequences was the impossibility of developing the teaching practice or attending to the students. Based on this, the main relationship between both issues studied in this article has been evidenced. However, it is worth questioning the effect this has on teachers.

3.2.3. Main consequences of bureaucratization and lack of external consideration: Low teacher involvement and limited opportunities for professional development

The teaching profession has manifested a gradual change with the implementation of changes derived from external regulation that have caused a need for teachers to adapt over time. With this evolution, a change was observed in the practice, as well as in the teachers themselves and their behavior. The most relevant changes have been derived from the detected social demands or the dynamics of the classroom. One of the most palpable, according to some teachers, is the relationship with the students and the difficulty in managing the classroom and the associated tasks.

I would tell you that I am more focused on what I am doing today. Yes, it is true that lately I give more importance to group management, because previously group management was more… I wouldn't say easier, but more rational, more establishing… The student knew where they were, and I was clear that I was the teacher. I am still clear that I am the teacher (D12:35).

In addition, teachers state that they are busier and more concerned about unnecessary administrative tasks and how this will impact their professional development. They spend a lot of time on administrative tasks that do not have a direct effect on teaching, or the quality of attention given to the students. They note that the administration itself is the main obstacle to the different professional development opportunities that may be offered to them and is also the impediment for important issues such as the promotion of professional relationships or the creation of spaces for them to be heard.

… another aspect, administrative issues that many times represent obstacles, for example, resources and help provided that facilitate the meeting, the exchange of experiences, and motivation, and on the other hand, sometimes they are an impediment for many things to be carried out (D20:35).

In this sense, teachers do not find greater motivation to carry out their work than their intrinsic one, although it supposes that, progressively, their involvement decreases. The profession itself and what it entails require a lot of involvement on their part. However, it is something that, over time, has been lost to the benefit of administrative tasks and the bureaucratization of the profession.

I don't like the idea of an official, of the bureaucratization of education. I think that education has an important implication, for me the role of the teacher as a tutor, as a person who guides a student […] For me that is the important thing, for me now the role of the group has been slightly lost; that is, before, when I started, there was more vocation, there was more involvement, and there was a will to change the world through education (D11:2).

4. Discussion and conclusion

After the interviews were conducted and analyzed, several ideas were extracted about the teachers’ perception of the bureaucratization of their work and the external consideration that other agents outside the center (in this case, the families) have about their function.

As has been verified in previous sections, there is a relevant difference in terms of teachers with more experience and novices regarding both topics. More specifically, older and therefore more experienced teachers place more emphasis on the overload of work that they have assumed over the years, while younger teachers and those with less experience show little concern in this regard (Cortez et al., 2013). This may be due to the fact that, having recently started their professional career, they assume administrative functions as inherent to their role, without perceiving the differences that the profession has gradually been subjected to (Imbernón, 1994). Something similar occurs with the external consideration, as most experienced teachers express their concern about the external consideration that has been shaped around them (Díaz et al., 2010). However, both issues are currently latent and have been included in the discourse of the teachers interviewed.

The teaching staff has expressed a negative consideration toward both categories (bureaucratization and external consideration). Teachers with more experience recognize the change that the teaching practice has undergone because they have seen their workload, as well as its complexity and difficulty, increase over the years (Avilés, 2019; Sanz Ponce et al., 2020). In this sense, they consider that they must carry out their functions as teachers and also the extra tasks that have been imposed on them, tasks that are mostly of an administrative nature and which they must face on a day-to-day basis (Prieto, 2008). Thus, the teachers interviewed allude to the amount of bureaucratic work and action protocols that they adhere to systematically (Day, 2011; Londoña Montoya et al., 2019), which result in greater regulation and control by the administration and higher bodies, causing a certain reticence in the teachers (Sachs and Mockler, 2012).

The teachers interviewed also refer directly to the legislative and government changes that have been implemented in recent years, obviously affecting the educational practice. On the one hand, teachers consider that, despite all the legislative changes they have experienced, they have not perceived an improvement in the conditions of and for their teaching practice, nor a reduction of functions. On the contrary, each new change has resulted in an increase and/or overload of tasks (Bolívar, 2012; Guzmán and Javier, 2020). Likewise, they argue that there have been numerous reforms that, even before being reviewed and implemented, or before being put into practice, have been repealed and replaced by different ones (sometimes related to changes in the government). This is perceived by teachers as being detrimental to the performance of their duties because they must dedicate a large number of hours and great effort to adapt, modify, and renew their tasks based on the new legislative requirements. This takes up time that teachers feel could be dedicated to other aspects that are more related to their practice and that can directly benefit the teaching–learning process, such as innovation, training, the preparation of materials, classes, creativity, and teamwork (Hargreaves and Shirley, 2012).

On the other hand, the participants in this study consider that all these changes provoke in them a feeling of continuous vigilance (Bolívar, 2012; Guzmán Marín, 2018). Teachers feel pressured by the number of procedures and administrative tasks that they must carry out and the accountability they must exhibit before the governing bodies and the administration. This implies that teachers must spend more time solving problems and limiting their role to ensure adherence to protocols.

The increase in external regulation to which teachers have been subjected has resulted in a negative influence on their external consideration. Teachers recognize that the society has a negative view of their work without being aware of the large number of tasks they must carry out to perform their role (Day, 2011).

In short, the overload of administrative and management work faced by teachers when performing tasks that are sometimes more administrative than pedagogical, together with the prejudices that society has created around their work, have led to a decrease in their social consideration. Therefore, we can deduce that both factors are linked.

4.1. Potential research limitations and practical implications

The limitations of this cross-sectional study must be taken into consideration. On the one hand, it is evident that the various changes to the teaching practice are mostly perceived by older teachers and not so much by the younger ones. This is because the latter, with their limited teaching experience, have not had time to appreciate these changes; for them, this work overload is assumed to be normal. On the other hand, it should be highlighted that the period in which this study was conducted may have an effect on the results. As this investigation was carried out after the coronavirus disease 2019 pandemic, different teachers were influenced by the various changes that emerged post the pandemic and to which they have had to adapt with hardly any time to think or reflect on their teaching practice. Phenomena like this have already been presented in previous research and are referred to as “cohort effects” (Costanza et al., 2012).

Another limitation that this research may present is the sample. Despite attempts to collect a broad and representative sample, ideas or perceptions characteristic of a delimited area have been expressed on occasions. Although the convergence of the data is significant, the management of decentralized education (which is not carried out at the national level) means that the particularities of each jurisdiction can emerge. However, looking into the differences between each of the autonomous communities could be seen as a future line of inquiry.

One of the main implications that we identified is the notable increase in the complexity of the teaching practice to the detriment of the quality of the education offered, limiting aspects such as teacher development or their dedication to improving teaching with their students, undertaking training, innovating, and working as a team. In this sense, Caena (2011) stated that the teaching task requires a great deal of involvement on the part of the teaching staff. Thus, the way in which the involvement of teachers is affected by issues such as work overload, the assumption of new tasks, and the increase in the difficulty to carry out their role are possible lines of future research.

From the perceptions of the teachers interviewed, the following practical implications or proposals for improvement for the future of the teaching function can be deduced. On the one hand, it is necessary to reduce the bureaucratic burden by ensuring the presence of full-time administrative staff in the centers. This figure could be the key to reducing the workload of the teaching staff. Secondly, time should be guaranteed for coordination and joint planning among teachers, which would imply reducing the number of hours of direct class time with students for teachers. Finally, there is a need to recognize the efforts made in teacher training and innovation through work incentives. This is due to the constant and little recognized action of teachers to improve and innovate in their classrooms.

Data availability statement

The data analyzed in this study is subject to the following licenses/restrictions: Not included to preserve the anonymity of the participants and their personal opinions. Requests to access these datasets should be directed to abraham.bernardez@um.es.

Ethics statement

The studies involving human participants were reviewed and approved by Human Research Ethics Committee of the University of Murcia. The patients/participants provided their written informed consent to participate in this study.

Author contributions

MP-C and MG-H: conceptualization. AT-S: methodology. MG-H and AT-S: software. AB-G, MG-H, and AT-S: formal analysis. MP-C, MG-H, and AT-S: investigation. AB-G, MG-H, and AT-S: data curation. MP-C, MG-H, AB-G, and AT-S: writing—original draft preparation and writing—review and editing. MG-H: supervision. All authors contributed to the article and approved the submitted version.

Funding

The authors disclose receipt of the following financial support for the research, authorship, and/or publication of the article: this work was supported by the Ministry of Science and Innovation (Spain), AEI (Spain), and European Regional Development Fund (EU) [Project RTI2018-098806-B-I00].

Acknowledgments

We thank all the participants and organizations involved in the study for their commitment and support.

Conflict of interest

The authors declare that the research was conducted in the absence of any commercial or financial relationships that could be construed as a potential conflict of interest.

Publisher’s note

All claims expressed in this article are solely those of the authors and do not necessarily represent those of their affiliated organizations, or those of the publisher, the editors and the reviewers. Any product that may be evaluated in this article, or claim that may be made by its manufacturer, is not guaranteed or endorsed by the publisher.

Footnotes

1. ^The project is titled "Intergenerational Professional Development in Education: Implications for Teacher Induction" and is funded by the Ministry of Science, Innovation and Universities. Reference: RTI2018-098806-B-I00.

References

Avalos, B., Cavada, P., Pardo, M., and Sotomayor, C. (2010). La profesión docente: Temas y discusiones en la literatura internacional. Estudios Pedagógicos 36, 235–263. doi: 10.4067/S0718-07052010000100013

Avilés, Guadalupe Cesario. (2019). La carga administrativa en docentes comisionados a función directiva, como factor de estrés y el impacto en su tarea de enseñar, Revista Caribeña de Ciencias Sociales (febrero 2019). Available at: https://www.eumed.net/rev/caribe/2019/02/carga-administrativa-docentes.html (Accessed October 15, 2022).

Barber, Michael, and Mourshed, Mona. (2008). Cómo hicieron los sistemas educativos con mejor desempeño del mundo para alcanzar sus objetivos. Chile: Mckinsey.

Berkovich, I., and Grinshtain, Y. (2021). A review of rigor and ethics in qualitative educational administration, management, and leadership research articles published in 1999–2018. Leadersh. Policy Sch. 20, 1–16. doi: 10.1080/15700763.2021.1931349

Bolívar, Antonio. (2012). El proceso de burocratización de la escuela. Una rigidez que impide el incremento de profesionalidad y no se corresponde con la enseñanza y el aprendizaje de hoy. Revista Crítica n°. 982, pp: 28–32.

Braun, V., and Clarke, V. (2006). Using thematic analysis in psychology. Qual. Res. Psychol. 3, 77–101. doi: 10.1191/1478088706qp063oa

Braun, V., and Clarke, V. (2021). Can I use TA? Should I use TA? Should I not use TA? Comparing reflexive thematic analysis and other pattern-based qualitative analytic approaches. Couns. Psychother. Res. 21, 37–47. doi: 10.1002/capr.12360

Caena, Francesca. (2011). Literature review. Teachers' core competences: Requirements and development. Brussels: European Commission.

Camacho, N. E. O. (2020). Tiempos de resignificar la función del maestro, de la escuela y la educación. Maestros Pedagogía 2, 114–121.

Colomo, E., and Aguilar, Á. I. (2019). ¿Qué tipo de maestro valora la sociedad actual? Visión social de la figura docente a través de Twitter. Bordón 71, 9–24. doi: 10.13042/Bordon.2019.70310

Cortez, Q., Karina, F. Q., Valeria, V. O., Isabel,, and Guzmán, C. (2013). Creencias docentes de profesores ejemplares y su incidencia en las prácticas pedagógicas. Estudios Pedagógicos XXXIX, 97–113. doi: 10.4067/S0718-07052013000200007

Costanza, D., Badger, J., Fraser, R., Severt, J., and Gade, P. (2012). Generational differences in work-related attitudes: a meta-analysis. J. Bus. Psychol. 27, 375–394. doi: 10.1007/s10869-012-9259-4

Creswell, J. W. (2015). “Revisiting mixed methods and advancing scientific practices” in In The Oxford Handbook of Multimethod and Mixed Methods Research Inquiry. eds. S. Hesse-Biber and R. B. Johnson (UK: Oxford University Press), 57–71.

Day, C. (2006). Pasión por enseñar. La identidad personal y profesional del docente y sus valores. Madrid: Narcea.

Day, Christopher. (2011). Uncertain professional identities: managing the emotional contexts of teaching. in C. Day and J. Chi-Kin Lee (eds.), New Understandings of Teacher’s Work: Emotions and Educational Change. Dordrecht: Springer, pp. 45–64.

Díaz, C., Martínez, P., Roa, I., and Sanhueza, G. (2010). Los docentes en la sociedad actual: sus creencias y cogniciones pedagógicas respecto al proceso didáctico. Polis, Revista de la Universidad Bolivariana 9, 421–436. doi: 10.4067/S0718-65682010000100025

Esteve, José Manuel. (2006). Identidad y desafíos de la condición docente. En Tenti Fanfani Emilio. El oficio docente: vocación, trabajo y profesión en el siglo XXI. Buenos Aires: Siglo XXI, pp: 16–69.

EU. (2013). Suporting teacher competence for better learning outcomes. Disponible en ec. Available at: europa.eu/dgs/education_culture/teachercomp_en.pdf (Accessed October 1, 2022).

Friese, Susanne. (2019). Qualitative Data Analysis with ATLAS.Ti. Thousand Oaks, CA: Sage Publication. 3rd

Fullan, Michael. (2002). Las fuerzas del cambio. Explorando las profundidades de la reforma educativa. Madrid: Akal.

García, Checa Purificación, Aísa, Carmen Herrero, and Bejarano, Esther Blázquez. (1991). Los padres en la comunidad educativa. Madrid: Castalia.

Sanz Ponce, R., González Bertolín, A., and López Luján, E. (2020). Docentes y pacto educativo: una cuestión urgente. Contextos educativos 26, 105–120. doi: 10.18172/con.4399

Gonzalvez Perez, V. (2016). “¿Carácter o responsabilidad profesional? más allá de la burocratización de la enseñanza?” in Isabel, Carrillo i Flores (coord.). Democracia y Educación en la formación (Barcelona: Universitat de Vic-Universitat Central de Catalunya), 199–203.

Guzmán, Nivelo, and Javier, Pablo. (2020). El malestar docente y su incidencia en el establecimiento del vínculo educativo. Available at: http://repositorio.ucsg.edu.ec/handle/3317/15848 (Accessed November 4, 2022).

Guzmán Marín, F. (2018). La experiencia de la evaluación docente en México: análisis crítico de la imposición del servicio profesional docente. RIEE. Revista Iberoamericana de Evaluación Educativa 11, 135–158. doi: 10.15366/riee2018.11.1.008

Hargreaves, A. (1992). Time and teachers work: an analysis of the intensification thesis. Teachers Collee. Record 94, 87–108.

Hargreaves, A. (2003). Teaching in the Knowledge Society: Education in the Age of Insecurity Open. Philadelphia: University Press.

Hargreaves, A. (2005). Educational change takes ages: life, career and generational factors in teachers' emotional responses to educational change. Teach. Teach. Educ. 21, 967–983. doi: 10.1016/j.tate.2005.06.007

Hargreaves, Andy, and Shirley, Dennis. (2012). La cuarta vía. El prometedor futuro del cambio educativo. Barcelona: Octaedro.

Hattie, Jonh. (2017). Aprendizaje visible para profesores. Maximizando el impacto en el aprendizaje. Madrid: Paraninfo.

Hwang, S.-S. (2008). Utilizando software de análisis de datos cualitativos: una revisión de Atlas.ti [Revisión del software Atlas.Ti]. Revista informática de ciencias sociales 26, 519–527. doi: 10.1177/0894439307312485

Imbernón, Francesc. (1994). La formación permanente y el desarrollo profesional del profesorado. En Francesc Imbernón (ed.), La formación y el desarrollo profesional del profesorado: Hacia una nueva cultura profesional. Barcelona: Graó, pp: 58–59.

Londoña Montoya, S., Gómez Acosta, G., and González Carreño, V. (2019). Percepción de los docentes frente a la carga laboral de un grupo de instituciones educativas colombianas del sector público. Espacios 40:26.

Lui, X. S., and Ramsey, J. (2008). Teachers’ job satisfaction: analyses of the teacher follow-up survey in the United States for 2000-2001. Teach. Teach. Educ. 24, 1173–1184. doi: 10.1016/j.tate.2006.11.010

Moreno, T., and Yreidys, M. (2019). Gerencia Educativa Versus Satisfacción Laboral del Docente Actual: Una Mirada Analítica. Revista Scientific 4, 369–380. doi: 10.29394/Scientific.issn.2542-2987.2019.4.12.20.369-380

Morgan, D. (2008). “Snowball sampling” in The SAGE Encyclopedia of qualitative research methods. ed. L. Given (Thousand Oaks, CA: SAGE Publications Inc.), 816–817.

Patton, Michael Quinn. (2015). Qualitative Evaluation and Research Methods. Thousand Oaks, CA: Sage.

Pérez, V., and Rodríguez, J. C. (2013). “Educación y prestigio docente en España: la visión de la sociedad” in El prestigio de la profesión docente en España. Percepción y realidad. Informe. ed. M. Esteban Villar (Madrid: Fundación Botín y Fundación Europea Sociedad y Educación), 33–108.

Perrenoud, Philippe. (2012). Cuando la escuela pretende preparar para la vida. ¿Desarrollar competencias o enseñar otros saberes? Barcelona: Graó.

Portela, P., Antonio, B. G., Abraham, M. G., José, J., Cano, N., and Miguel, J. (2022). Intergenerational professional development and learning of teachers: a mixed methods study. Int. J. Qual. Method 21, 160940692211332–160940692211310. doi: 10.1177/16094069221133233

Prieto, E. (2008). El papel del profesorado en la actualidad. Su función docente y social. Foro de educación 10, 325–345.

Sachs, J., and Mockler, N. (2012). “Performane cultures of teaching: threat or opportunity?” in International Handbook of Teacher and School Development. ed. C. Day (London: Routledge), 33–43.

Sampieri, Roberto Hernández, Carlos, Fernández Collado, and Pilar, Baptista Lucio. (2014). Metodología de Investigación (6th). México: McGraw-Hill.

Soratto, J., Denise, P., and Suanne, F. (2020). Thematic content analysis using ATLAS.Ti software: potentialities for research's in health. Rev. Bras. Enferm. 73:e20190250. doi: 10.1590/0034-7167-2019-0250

Tracy, Sarah J. (2020). Qualitative Research Methods: Collecting Evidence, Crafting Analysis, Communicating Impact (2nd). West Sussex: Wiley.

Yadav, D. (2021). Criteria for good qualitative research: a comprehensive review. Asia Pac. Educ. Res. 31, 679–689. doi: 10.1007/s40299-021-00619-0

Keywords: teaching conceptions, teaching functions, teaching profession, bureaucratization, external consideration, cross-sectional study

Citation: García-Hernández ML, Bernárdez-Gómez A, Porto-Currás M and Torres-Soto A (2022) Changes in teaching from the perspective of novice and retired teachers: Present and past in review. Front. Educ. 7:1068902. doi: 10.3389/feduc.2022.1068902

Edited by:

Luiz Sanches Neto, Federal University of Ceara, BrazilReviewed by:

Valentine Joseph Owan, University of Calabar, NigeriaMarília Favinha, University of Evora, Portugal

María Isabel Gómez Núñez, Universidad Internacional De La Rioja, Spain

Copyright © 2022 García-Hernández, Bernárdez-Gómez, Porto-Currás and Torres-Soto. This is an open-access article distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution License (CC BY). The use, distribution or reproduction in other forums is permitted, provided the original author(s) and the copyright owner(s) are credited and that the original publication in this journal is cited, in accordance with accepted academic practice. No use, distribution or reproduction is permitted which does not comply with these terms.

*Correspondence: Abraham Bernárdez-Gómez, ✉abraham.bernardez@um.es

María Luisa García-Hernández

María Luisa García-Hernández  Abraham Bernárdez-Gómez

Abraham Bernárdez-Gómez