Key Points

-

Provides an overview of evidence related to minor oral surgery patients who are taking specific medication.

-

Defines and summarises the role of evidence-based practice.

-

Gives brief descriptions of the importance and legalities of the consent process in minor oral surgery.

Abstract

This article provides readers with an overview of available evidence in relation to providing care to patients in different medical circumstances within oral surgery. There is evidence available to support discussions with patients taking particular medications (such as bisphosphonates, anticoagulants and corticosteroids) and also to try to prevent certain complications (such as 'dry socket'). In order to reduce the risks of potential morbidities, either perioperatively or postoperatively, operators must use high-quality, reliable and informed protocols, management techniques, advice and interventions to provide patients with the best care. These are used both preoperatively and postoperatively and patients should be consented appropriately, in a manner tailored to their own individual circumstances, but also using available evidence to explain the benefits and harms of any given procedure. In this short series we will outline and discuss common pre- and postoperative management techniques, protocols and instructions, and the evidence available to support these.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

'POIG' (Postoperative instructions given) is a term that will be familiar to many operators, clinicians and support staff. There is an array of advice, instruction and guidance delivered by healthcare professionals on a daily basis and this may vary on what is delivered and the method by which it is conveyed. Oral surgery still remains one of the most invasive areas within dentistry for the operator to carry out treatments with potentially serious morbidities. This short series of articles will assess discussed risks, advice, management techniques and interventions commonly issued to patients across the profession within minor oral surgery (MOS), both preoperatively and postoperatively.

What is evidence?

Evidence-based practice can be defined as 'the explicit and judicious use of current best clinical research evidence to guide healthcare decisions'. It integrates this best research evidence with clinical expertise and patient values. The aim of evidence-based practice is to optimise clinical outcomes and the patient's quality of life.1

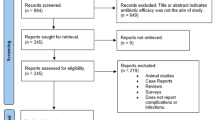

Within dentistry, the amount of credible, recent, strong evidence is lacking, especially when mirrored with the literature available within medicine.2 This continues to be the case when assessing the use of guidelines available in dentistry, which have been questioned by some authors.3 One example of this would be the 15-year-old NICE guidelines for the removal of impacted wisdom teeth,4 which were discussed in an article in 2013:1 the authors alluded to the fact that these particular guidelines were produced by a 'working group' of individuals, none of which had any form of dental qualification; these guidelines have not been reviewed or updated since 2000. Nevertheless, dentistry follows the same model in relation to the hierarchy of evidence (Fig. 1). Systemic reviews with incorporated meta-analysis remain the strongest and best forms of evidence.

Research methods differ in methodology, time, design, cost and ultimately strength. Table 1 very briefly outlines the various research methods available. In order to be in the best position, it is the author's belief that healthcare professionals must not only be aware of the latest research, but able to critically appraise the literature to assist a decision-making process, which should already be supplemented by sound clinical skills – including taking a good history, carrying out a thorough high-quality examination and also individual patient risk assessments. Various risk assessment tools exist for general dental practitioners already, and some of these have been incorporated physically into daily treatment plans (for example, certain NHS pilot contracts have incorporated a 'RAG' system to aid categorisation of patient risk to dental disease5). The methodology and the evidence used to formulate such pilots is largely unclear; however, evidence-based resources to aid risk assessment do exist; one such resource is the preventative toolkit produced by the Department of Health, Delivering better oral health.6 Unlike the NICE guidelines mentioned earlier, this toolkit has been regularly updated and consists of current evidence-based advice. The skill of critical appraisal is as any other in dentistry and requires knowledge, experience and practice; therefore, interested readers are encouraged to engage in further reading and are directed to other texts regarding this wide-ranging topic.7,8,9,10,11,12,13,14,15,16,17

One organisation that aids clinicians, investigators, researchers, patients and members of the public make such appraisals is the Cochrane Collaboration.18 Systematic, up-to-date reviews (with meta-analysis where possible) are prepared, maintained and available, providing an integral resource to be able to make evidence-based clinical decisions.

Pre-/postoperative protocols

Generations of healthcare professionals have delivered important preoperative intervention and aftercare messages to patients across many different specialities. Within dentistry, nearly all procedures are followed by some form of advice or instruction – and some of these also require management before any treatment is carried out. For some procedures there is clear and concise guidance, for example the prescription of antimicrobials in primary dental care19,20 (see below). The advice delivered following other common procedures is a little more conspicuous – an example of this would be explaining to patients to avoid biting on their lip/chin following treatment under local anaesthetic. Both the experienced and inexperienced clinician will be all too aware of the potential consequences of litigation and complaints if effective communication has not been delivered preoperatively, or if there are complications within the treatment carried out – even if this has previously been explained and included within the consent (see later).

Preoperative

Protocols for managing patients before any particular surgery may involve instructions, procedures or particular investigations. Several of these have been discussed (mainly within the medical context) by NICE21 and some of their guidance is likely to be used within the dental profession.4,22 Perhaps one of the most well-renown preoperative recommendations is regarding Antimicrobial prophylaxis against infective endocarditis.22 This particular document is evidence-based and advises against the use of either antimicrobials or chlorhexidine gluconate mouthwash for prophylactic medicaments for patients undergoing dental procedures. The clinical implications of this document have been evaluated as recently as a few months ago. Dayer et al. analysed prescription versus non-prescription for the antibiotic prophylaxis in relation to infective endocarditis, in England, over a period of just over 12 years. Their findings were a reduced number of prescriptions since the guidelines were introduced in 2008, but also an increase in the incidence of cases of infective endocarditis.23 The results are statistically significant for both low and high-risk patients.23 Another example of an infamous but perhaps more under-used regimen is the use of diazepam for anxious patients, before attending appointments. The use of oral sedatives for nervous, fearful and anxious patients has been well-documented.19,24

Within oral surgery procedures, clinicians are now likely to be aware of patients that are at a greater risk of complications. Some examples of these risk-groups would be patients taking certain medications – such as anticoagulants, antiplatelets, bisphosphonates, steroids or the oral contraceptive pill (OCP). Although we will briefly discuss some of the guiding evidence for the management of these patients; there are many other medications and medical conditions that affect the dental patient, and for this the reader is referred elsewhere.25

Bisphosphonates and anti-bone-resorptive medications

Recent research text and articles have discussed the existence of bisphosphonate-related osteonecrosis of the jaw (BRONJ), including the condition, the effects of these powerful drugs, and the management of patients.26,27,28,29,30,31,32,33,34,35,36,37 The topic of BRONJ has become so publicised that UK guidance in this area is now readily available for clinicians,38,39 although this guidance originates mainly from 'expert-opinion' or clinical-led questionnaires/surveys.

One of the more recent articles mentions that a similar necrotic process within the jaws exists with some non-bisphosphonate anti-resorptive drugs (for example, denosumab), which has prompted the term 'ARONJ' (anti-resorptive-related osteonecrosis of the jaw).37

Advocacy for a preventive dental regimen is well documented.32,40,41 For those patients on oral bisphosphonates, and in circumstances in which there is no option but to proceed with dentoalveolar surgery, drug holidays have been proposed.28,42,43

The past, present and possible future use of bisphosphonates should be enquired about when taking the patient's medical history. Patients must be categorised according to their risk (Table 2), which will consequently determine management, although the type of procedure and the experience of the clinician – although not currently well-researched or discussed – will also be important factors. In relation to oral surgery procedures: 'low-risk' patients may be treated in the primary care setting – simple extractions must be as atraumatic as possible, mucoperiosteal flaps should be avoided and good haemostasis should be achieved. For 'high-risk' patients, the best option is to contact the local oral surgery or oral/maxillofacial surgery specialist for advice in relation to whether oral surgery treatment and/or any treatment that will impact bone should be continued within primary care, or whether a referral will be necessary.32,39 ('High-risk' includes dento-alveolar surgery, dental implants, periapical procedures, periodontal surgery and deep root-planing.) Although it is clear that the type of procedure proposed may help aid a decision during risk assessment26,28,29,31,32,33,34,35,38,39little evidence exists regarding the relationship between clinical experience and risk assessment. There is currently no evidence supporting the use of antibiotic therapy or antiseptic oral rinse in reducing the risk of BRONJ.39

The common theme for the guidance produced within the UK is to emphasise the importance of the preventative approach (that is, reducing periodontal disease and dental infection) and to try to avoid future extractions and trauma to bone, hence minimising the risk of BRONJ developing.32,38,39 The legal implications related to BRONJ have been discussed in a thorough article that readers may find helpful in both primary and secondary care settings.44 This article seems to suggest a thorough scrutiny of events – including diagnosis, prescriptions, management, treatments and referral – from the onset of a patient being prescribed bisphosphonates to immediately after developing BRONJ.44

Bleeding disorders and anticoagulants

A recently published article provides guidance on patients with haemophilia and congenital bleeding disorders.45 The authors suggest that treatment planning once again involves an assessment of risk (in this case 'bleeding-risk'), which is dependent on the bleeding disorder, the area and invasiveness of the surgery and the experience of the clinician.59 It is also suggested that any therapeutic agent should ideally be delivered preoperatively, ranging from a period of two hours prior, up to at the point of the procedure (depending on which agent is chosen).

The British Committee for Standards in Haematology published reviewed guidance in 2011, making recommendations for patients having dental surgical procedures.46 One of these recommendations was that oral anticoagulants should not be discontinued for the majority of patients requiring out-patient dental surgery, including dental extractions. This may be dependent on the stability and range of the patient's International Normalised Ratio (INR).47 Further guidance from other resources has emerged.48 These recommendations are similar to those that exist for patients on other agents that increase bleeding tendency: reduction of trauma, limiting dental extractions to four teeth in a single visit and advocating the thorough use of local haemostasis (that is, suturing, packs and pressure). Patients using vitamin-K antagonists (such as warfarin) should have the INR checked within 24 hours of the procedure (INR should be below 4 and demonstrate stability). No preoperative dose-testing or adjustment is currently recommended for the more recently developed oral anticoagulants (for example, dabigatran etexilate and rivaroxaban). In patients who have a recently placed cardiac stent, those with alcohol dependency and in patients with liver/kidney impairments, clinicians are advised to seek the advice of a senior medical colleague.48

Steroid therapy

In 2004, Gibson and Ferguson published proposed guidelines for clinicians following a critical review of the literature in relation to steroid cover.50 Their conclusions for primary care were that supplementary 'steroid cover' is not required for general dental procedures, including MOS treatment under local anaesthetic. This may not be the case under general anaesthesia, where the dose of the steroid and the duration of treatment are factors. This may warrant the use of perioperative administration of glucocorticoid supplementation.50

Patients with systemic signs of disease (for example, a spreading dental abcess) are recommended to have a prophylactic increase in steroid dose. For those with Addison's disease the dose must be doubled before significant dental treatment under local anaesthetic and this must be continued for 24 hours postoperatively.50

Postoperative

Similar methods may be used postoperatively as can be employed preoperatively; that is: instructions, procedures and well-delivered, specific advice can be used in isolation or in conjunction when managing the postoperative patient.

From a dental perspective, as mentioned above, the defence organisations have made general resources available electronically with immediate and easy access.51

Perhaps one of the most essential components for the patient and operator following surgery is analgesia. In particular for the patient, it is the author's view that this is a significant priority. The World Health Organisation confirms that pain management is the responsibility of healthcare professionals and has published guidance to assist clinicians.52 This has been supplemented by other relevant texts.53,54 Analgesic control will be further discussed in following articles in this short series.

One of the commonest complications encountered by clinicians in both primary and secondary care providing oral surgery procedures is alveolar osteitis ('dry socket'). We can now briefly discuss some of the postoperative care, advice and management techniques to avoid this familiar oral surgery complication, although a detailed account is available elsewhere.55

Dry Socket

Most preventative approaches used to avoid the development of dry socket have focused on the use of chlorhexidine gluconate (0.12% and 0.2%)56. A recent Cochrane systematic review reports some randomised-controlled trials do provide evidence of the benefits in the use of chlorhexidine gluconate oral rinse both preoperatively and postoperatively.54 Chlorhexidine gels have also demonstrated some benefits.58,59 Systemic prophylactic modalities are also available: there is vast evidence supporting the use of antibiotics both preoperatively and postoperatively to reduce the risk of developing dry socket59,70. However, the majority of this evidence relates to third molar removal, rather than extraction of other teeth56.

As well as the interventions available, practitioners will be familiar with the advice given to patients to minimise the risk of developing this painful condition. The OCP is the only known medication that is associated with developing dry socket. Sweet and Butler60 found a positive correlation between the use of the OCP and development of dry socket and one author has even suggested consideration of hormonal cycles to correspond with an appropriate time for any exodontia.61 Smoking is a habit that has been implicated as an aetiological factor in too many conditions to be able to list in this text, but is another risk factor in the development of dry socket. Patients are reminded to avoid smoking post-surgery. One study found the incidence of dry socket increased by 40% in patients who smoked on the day of tooth removal.62 Another part of the postoperative instructions to patients is to avoid physical dislodgement of the clot – often communicated as instruction to avoid spitting or rinsing. No current evidence exists in the literature to verify this theory in support of developing dry socket.

Postoperatively, effective communication remains as essential as it was preoperatively. In order to avoid patient dissatisfaction and confusion, as well as preventing unwanted complaints and litigation, the clear, concise and well-delivered nature of ongoing communication (even beyond completion of any procedure) cannot be emphasised enough. Some dental defence organisations have produced documentation available to all operators, clinicians and support staff free of charge. The author would encourage all dental healthcare professionals to extend their attentions to these valuable resources.51

Consent

Consent is an ongoing process (Fig. 2) and it is vital for clinicians to remember that a patient may withdraw this at any time.63,64 This topic is a large but logical one, which requires rigorous and thorough study to ensure the safety, quality and satisfaction (to both patients and operators) of treatment delivered. Various resources are available to professionals relating to this particular subject and the author would direct interested readers to the readily available documents.63,64,65,66

At the forefront of the majority of patient consenting seems to be an explanation of benefits and risks of treatment, but it is essential to include preoperative and postoperative information with regards to the procedure. Within the consent form there are designated areas to encourage clinicians to provide these.

In relation to evidence, a knowledge base that expands deep within the literature of a specific procedure may perhaps be more beneficial to colleagues and fellow clinicians but care and consideration needs to be exercised when presenting this information to the patient – sometimes this information may even be considered irrelevant, or, especially for the anxious patient, may form an exaggerated opinion of the nature of a particular risk.64 This is, however, not always the case. The 'prudent patient test' has been performed by courts to decide whether the patient has been given adequate information. This will vary from patient to patient – for example, a netizen may want each material risk of a given procedure, even if this is an exhaustive list. The individual nature of each patient makes this test a difficult one to perform.72 Courts may also seek to use the 'Bolam test', in which a medical professional should not be found guilty if a reasonably competent colleague in a similar position would have acted in the same way and the actions would be supported by a responsible medical body.64 In 1985, this was further affirmed in the Sidaway vs. Board of Governors of Bethlem Royal and the Maudsley Hospital case. The House of Lords concluded that the degree of risk disclosure is a matter of clinical judgement on part of the clinician, and the patient must be informed of any danger that is special in character or magnitude (or important to that particular patient) and supply sufficient information to enable the patient to make a balanced judgement.64 From a legal perspective, there is now increasing expectation that clinicians explain and advise patients of all the material risks that relate to a specific treatment/procedure and not only those material risks that a responsible body of medical professionals would provide. One example of this would be the Bolitho vs. City and Hackney Health Authority case.64

Before any consent process begins, clinicians must make the assessment of whether the individual providing it is competent.60,61,62 Perhaps the most common situation when this assessment is tested is the patient's age, and the existence of 'Gillick competence',63,64 which is particularly relevant for children. However, many situations and circumstances exist where the topic of consent is more complicated. For example, those patients in care, unable to demonstrate competence, in events where consent is unobtainable and disputes regarding care, treatments or procedures. In these cases it is always wise and ideal to contact an appropriate body to assist (for example, dental defence organisations and/or clinical bodies). This may not always be possible or practical in clinical practice, so it is essential that basic principles are followed (Table 3). For further reading and understanding of this large and complex topic, readers are referred to other resources.63,64,65,66

Whether or not profound and high-quality evidence has been used in explanation to patients, it is absolutely essential to remember the circumstances of each individual patient and undoubtedly these will never completely be the same (for example, nerve damage in relation to wisdom teeth removal67,68,69,70,71). Following the initial communication regarding consent, the signing of the appropriate and accurately presented consent form does not signal the conclusion of the process, but it is an ongoing process.

Summary

At undergraduate level, it is likely that most clinicians were taught the principles of evidence-based dentistry and the fundamentals that constitute the hierarchy of evidence. Perhaps some of the most invasive procedures the dentist will perform lie within oral surgery. The use of the literature to deliver high-quality preoperative and postoperative management, instructions, advice and protocols, which have sound evidence-base is the desirable goal for the provider, especially with treatments carrying such potential morbidities for patients. This is not always possible, but in some cases within dentistry, guidelines, advice sheets and toolkits may exist to aid decision-making for patient treatments and treatment plans. Some of the evidence used to produce such resources has been briefly discussed above and the author has chosen select topics within MOS. These brief examples highlight that although the qualities of clinical guidelines within dentistry have been criticised, other research and evidence does exist. When the clinician assesses this, the strength of such literature should be appraised – including the methodology in which they were constructed.

A vast amount of information is available to patients via a range of different resources in the modern day, but it is still vitally important for operators to realise that the responsibility to deliver this information must still be their own. In addition to this information, the modalities available to reduce the morbidities to patients are also plentiful and it remains imperative to communicate clearly and effectively, and to be satisfied that patients understand what information is being provided. The consent process is a crucial, mandatory opportunity to explain, describe and advise patients of the risks and benefits of accepting/not accepting a particular intervention or treatment. These risks would often include pre- and postoperative morbidities. Further discussion of common pre- and postoperative protocols, management techniques and instructions in relation to the removal of impacted wisdom teeth and endodontic surgery will be discussed in following articles.

References

Mansoor J, Jowett A, Coulthard P . NICE or not so NICE. Br Dent J 2013; 215: 209–212.

Ismael Al, Bader J D . Evidence-based dentistry in clinical practice. J Am Dent Assoc 2004; 135: 78–83.

Glenny A M, Worthington H V, Clarkson J E, Esposito M . The appraisal of clinical guidelines in dentistry. Eur J Oral Implantol 2009; 2: 135–143.

NHS National Institute for Clinical Excellence (NICE). NICE technology appraisal guidance number 1. Guidance on the extraction of wisdom teeth. NICE, 2000.

Department of Health. NHS dental contract pilots – Learning after first two years of piloting. 2014. Available at: https://www.gov.uk/government/uploads/system/uploads/attachment_data/file/282760/Dental_contract_pilots_evidence_and_learning_report.pdf (accessed 21 January 2015).

British Association of Community Dentistry. Delivering better oral health, 3rd ed. London: Department of Health, 2014.

Moles D . Further statistics in dentistry: Introduction. Br Dent J 2002; 193: 375.

Petrie A, Bulman S, Osborn F J . Part 1: Research designs 1. Br Dent J 2002; 193: 377–380.

Petrie A, Bulman S, Osborn F J . Part 2: Research designs 2. Br Dent J 2002; 193: 435–440.

Petrie A, Bulman S, Osborn F J . Part 1: Clinical trials 1. Br Dent J 2002; 193: 495–498.

Petrie A, Bulman S, Osborn F J . Part 2: Clinical trials 2. Br Dent J 2002; 193: 557–561.

Petrie A, Bulman S, Osborn F J . Diagnostic tests for oral conditions. Br Dent J 2002; 193: 621–626.

Petrie A, Bulman S, Osborn F J . Multiple linear regression. Br Dent J 2002; 193: 675–682.

Petrie A, Bulman S, Osborn F J . Repeated measures. Br Dent J 2003; 194: 17–22.

Petrie A, Bulman S, Osborn F J . Systematic reviews and meta-analysis. Br Dent J 2003; 194: 73–78.

Petrie A, Bulman S, Osborn F J . Bayesian statistics. Br Dent J 2003; 194: 129–136.

Petrie A, Bulman S, Osborn F J . Sherlock Holmes, evidence and evidence-based dentistry. Br Dent J 2003; 194: 189–195.

The Cochrane Collaboration. The Cochrane Library, 1993. Available at: http://www.thecochranelibrary.com/view/0/index.html (accessed 18 May 2014).

Scottish Dental Clinical Effectiveness Programme. Drug prescribing for dentistry, 2nd ed. Dundee Dental Education Centre UK: NHS Scotland, 2011.

Faculty of Dental Practitioners (UK). Antimicrobial prescribing for general dental practitioners, 2nd ed. London: FGDP (UK), 2012.

National Institute of Clinical Excellence (NICE). The use of routine preoperative tests for elective surgery. Available at: https://www.nice.org.uk/guidance/cg3 (accessed 21 January 2015).

National Institute of Clinical Excellence (NICE). Prophylaxis against infective endocarditis, 1st ed. London: NICE, 2008.

Dayer M J, Jones S, Prendegast B, Baddour L M, Lockhart P B, Thornhill M H . Incidence of infective endocarditis in England, 2000–13: a secular trend, interrupted time-series analysis. Lancet 2014. doi:10.1016/S0140-6736(14)62007-9. [Epub ahead of print]

Donaldson M, Gizzarelli G, Chanpong B . Oral sedation: a primer for anxiolysis of the adult patient. Anesth Prog 2007; 54: 118–129.

Scully C . Medical problems in dentistry, 7th ed. London: Elsevier, 2013.

Vescovi P, Nammour S . Bisphosphonate-related osteonecrosis of the Jaw (BRONJ) therapy. A critical review. Minerva Stomatol 2010; 59: 181–203, 204–213.

Sharma D, Ivanovski S, Slevin M et al. Bisphosphonate-related osteonecrosis of the jaw (BRONJ): diagnostic criteria and possible mechanisms of an unexpected anti-angiogenic side-effect. Vasc Cell 2013; 5: 1.

Ruggiero S L, Dodson T B, Assael L A et al. American Association of Oral and Maxillofacial Surgeons position paper on bisphosphonate-related osteonecrosis of the jaws. Aust Endod J 2009; 35: 119–130.

Pazianas M, Miller P, Blumentals W A, Bernal M, Kothawala P . A review of the literature on osteonecrosis of the jaw in patients with osteoporosis treated with oral bisphosphonates: prevalence, risk factors and clinical characteristics. Clin Ther 2007; 29: 1548–1558.

Fedele S, Kumar N, Davies R, Fiske J, Greening S, Porter S . Dental management of patients at risk of osteochemonecrosis of the jaws: a critical review. Oral Dis 2009; 15: 527–537.

Assael L A . Oral bisphosphonates as a cause of bisphosphonate-related osteonecrosis of the jaws: clinical findings, assessments of risks, and preventative strategies. J Oral Maxillofac Surg 2009; 67(5 Suppl): 35–43.

Arrain Y, Masud T . Recent recommendations on Bisphosphonate-associated Osteonecrosis of the Jaw. Dent Update 2008; 35: 238–242.

McLeod N M H, Davies B J B, Brennan P A . Bisphosphonate osteonecrosis of the jaws: an increasing problem for the dental practitioner. Br Dent J 2007; 203: 641–644.

Pancholi M . Oral and intravenous bisphosphonate-induced osteonecrosis of the jaws: history, etiology, prevention and treatment. Br Dent J 2007; 203: 56–57.

Patel V, McLeod N M, Rogers S N, Brennan P A . Bisphosphonate osteonecrosis of the jaw – a literature review of UK policies versus international policies on bisphosphonates, risk factors and prevention. Br J Oral Maxillofac Surg 2011; 49: 251–257.

López-Cedrún J L, Sanromán JF, García A et al. Oral bisphosphonate-related osteonecrosis of the jaws in dental implant patients: a case series. Br J Oral Maxillofac Surg 2013; 51: 874–879.

Ruggiero S . Osteonecrosis of the jaw: BRONJ and ARONJ. Faculty Dent J 2014; 5: 90–93.

Faculty of General Dental Practitioners (UK). National study on avascular necrosis of the jaws including bisphosphonate-related necrosis. London: FGDP (UK), 2012.

Scottish Dental Clinical Effectiveness Programme. Oral health management of patients prescribed bisphosphonates. Dundee Dental Education Centre: NHS Scotland, 2011.

Krygidis A, Tzellos T, Toulis K et al. An evidence-based review of risk reductive strategies for osteonecrosis of the jaws amongst cancer patients. Curr Clin Pharmacol 2013; 8: 124–134.

Bonacina R, Mariani U, Villa F, Villa A . Preventative strategies and clinical implications for bisphosphonate-related osteonecrosis of the jaw: a review of 282 patients. J Can Dent Assoc 2011; 77: b147.

Hellstein J, Adler R, Edwards B et al. Managing the care of patients receiving antiresorptive therapy for prevention and treatment of osteoporosis. J Am Dent Assoc 2011; 142: 1243–1251.

Damm D, Jones D . Bisphosphonate-related osteonecrosis of the jaws: a potential alternative to drug holidays. Gen Dent 2013; 51: 33–38.

Lo Russo L, Ciavarella D, Buccelli C et al. Legal liability in bisphosphonate-related osteonecrosis of the jaw. Br Dent J 2014; 217: 273–278.

Anderson J A M, Brewer A, Creagh D et al. Guidance on the dental management of patients with haemophilia and congenital bleeding disorders. Br Dent J 2013; 215: 497–504.

Perry D J, Nokes T J C, Heliwell P S . Guidelines for the management of patients on oral anticoagulants requiring dental surgery. London: British Committee for Standards in Haematology, 2007 (reviewed 2011).

Sime G . Dental management of patients taking oral anticoagulant drugs. April 2012. Available at: www.abaoms.org.uk/docs/Dental_management_anticoagulants.doc (accessed October 2014).

Kerr R, Ogden G, Sime G . Anticoagulant guidelines. Br Dent J 2013; 214: 430.

Gibson N, Ferguson J W . Steroid cover for dental patients on long-term steroid medication: proposed clinical guidelines based upon a critical review of the literature. Br Dent J 2004; 197: 681–685.

Resuscitation Council (UK). Medical emergencies and resuscitation standards for clinical practice and training for dental practitioners and dental care practitioners in general dental practice – a statement from the Resuscitation Council (UK). Resuscitation Council (UK), 2006. Revised December 2012.

Dental Protection. Exercise in risk management: post-operative instructions, 2013. Available at: http://www.dentalprotection.org/adx/aspx/adxGetMedia.aspx?DocID=1366 (accessed 17 May 2014).

World Health Organisation. Post-operative pain management, 2014. Available at: http://www.who.int/surgery/publications/Postoppain.pdf (accessed 18 May 2014].

Moore R A, Derry S, McQuay H J, Wiffen P J . Single dose oral analgesics for acute postoperative pain in adults. Cochrane Database Syst Rev 2011; 9: CD008659.

Ramsey M A . Acute postoperative pain management. Proc (Bayl Univ Med Cent) 2000; 13: 244–247.

Sharif M O, Dawoud B E S, Tsichlaki A, Yates J M . Interventions for the prevention of dry socket: an evidence-based update. Br Dent J 2014; 217: 27–30.

Daly B, Sharif M O, Newton T, Jones K, Worthington H V . Local interventions for the management of alveolar osteitis (dry socket). Cochrane Database Syst Rev 2012; 12: CD006968.

Torres-Lagares D, Gutierrez-Perez J L, Infante-Cossio P, Garcia-Calderon M, Romero-Ruiz M M. Randomized, double-blind study on effectiveness of intra-alveolar chlorhexidine gel in reducing the incidence of alveolar osteitis in mandibular third molar surgery. Int J Oral Maxillofac Surg 2006; 35: 348–351.

Torres-Lagares D, Infante-Cossio P, Gutierrez-Perez J L, Romero-Ruiz M M, Garcia-Calderon M, Serrera-Figallo M A. Intra-alveolar chlorhexidine gel for the prevention of dry socket in mandibular third molar surgery. A pilot study. Med Oral Patol Oral Cir Bucal 2006; 11: 179–184.

Lodi G, Figini L, Sardella A, Carrassi A, Del Fabbro M, Furness S . Antibiotics to prevent complications following tooth extractions. Cochrane Database Syst Rev 2012; 11: CD003811.

Sweet J B, Butler D P . Predisposing and operative factors: effect on the incidence of localized osteitis in mandibular third-molar surgery. Oral Surg Oral Med Oral Pathol 1978; 46: 206–215.

Cohen M E, Simecek J W . Effects of gender-related factors on the incidence of localized alveolar osteitis. Oral Surg Oral Med Oral Pathol Oral Radiol Endod 1995; 79: 416–422.

Sweet J B, Butler D P . The relationship of smoking to localized osteitis. J Oral Surg 1979; 37: 732–735.

Dental Protection. Consent, 1st ed. London: Dental Protection Limited, 2013.

British Dental Association. Ethics in dentistry, 1st ed. London, BDA, 2009.

General Dental Council. Standards for the dental team, 1st ed. London: GDC, 2013.

General Medical Council. Consent: patients and doctors making decisions together, 1st ed. London: GMC, 2008.

Loescher A R, Smith K G, Robinson P P . Nerve damage and third molar removal. Dent Update 2003; 30: 375–382.

Renton T . Oral Surgery: part 4. Minimising and managing nerve injuries and other complications. Br Dent J 2013; 215: 393–399.

Renton T . Minimising and managing nerve injuries in dental surgical procedures. Faculty Dent J 2011; 2: 164–171.

Robert R C, Bachetti P, Pogrel A . Frequency of trigeminal nerve injuries following third molar removal. J Oral Maxillofac Surg 2005; 63: 732–735.

Grant S, Sivarajasingam V . Incidence of inferior alveolar and lingual nerve paraesthesia following mandibular third molar extractions: a retrospective audit of 235 cases. Br J Oral Maxillofac Surg 2011; 49S: S26–S116.

Satyanarayana Rao K H . Informed consent: an ethical obligation or legal compulsion? J Cutan Aesthet Surg 2008; 1: 33–35.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Additional information

Refereed Paper

Rights and permissions

About this article

Cite this article

Mansoor, J. Pre- and postoperative management techniques. Before and after. Part 1: medical morbidities. Br Dent J 218, 273–278 (2015). https://doi.org/10.1038/sj.bdj.2015.144

Accepted:

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/sj.bdj.2015.144

This article is cited by

-

Erratum: Corrigendum

British Dental Journal (2015)

-

Pre- and postoperative management techniques. Part 3: Before and after — Endodontic surgery

British Dental Journal (2015)