Milk and milk products are nutrient-dense foods, providing several micronutrients important for health across the lifespan, including I, K, B vitamins and Ca(Reference Auestad, Hurley and Fulgoni1). Childhood is a crucial period for skeletal growth and optimisation of peak bone mass, during which adequate Ca intake is essential(Reference Bronner2). Due to the role of Ca in bone mineralisation, inadequate intake in childhood can contribute to an increased risk of bone-related diseases, such as osteoporosis later in life(Reference Zhu and Prince3–Reference Abou Neel, Aljabo and Strange5). Dairy products, such as milk and yogurt, are rich sources of Ca (115–120 mg/100 g of milk(6)) and are considered to be the most affordable source of Ca in the American diet(Reference Hess, Cifelli and Agarwal7). Dairy products are also sources of protein, carbohydrates, unsaturated and SFA(Reference Auestad, Hurley and Fulgoni1). While excess consumption of saturated fat is of public health concern due to its association with increased risk of CVD and obesity, previous research has demonstrated a neutral or inverse association between milk and dairy products consumption and obesity and measures of adiposity in childhood(Reference Dougkas, Barr and Reddy8). International dietary guidelines generally recommend the consumption of two to three servings of dairy products daily for children aged under 9 years, and three to five servings are recommended for children above 9 years(Reference Dror and Allen9). Despite recommendations and its nutritional contribution to the diet, cow’s milk consumption among children in developed countries such as Ireland, the USA, France and Germany has decreased over the past decade(Reference Dror and Allen9–11).

In a systematic review of interventions promoting dairy products intake among school-aged children, all interventions targeting dairy products or Ca intake alone were deemed to be effective in improving dairy products consumption; however, the majority of the reviewed interventions promoted dairy products intake as part of a larger dietary intervention(Reference Hendrie, Brindal and Baird12). Similarly, Srbely et al. reported a lack of interventions targeting dairy products alone in preschool-aged children(Reference Srbely, Janjua and Buchholz13). This highlights the need for effective dairy products interventions, which require an understanding of the determinants of dairy products consumption throughout childhood.

A wide variety of personal, interpersonal and environmental factors influence eating behaviours in children. While childhood is a vital period for physiological development, it is also a crucial life stage for the development of food behaviours and preferences. Taste preferences influence food choice throughout the lifespan and those developed early in childhood can track into adolescence and adulthood(Reference De Cosmi, Scaglioni and Agostoni14). However, food preferences and behaviours can be modified, particularly when a variety of interpersonal and environmental influences emerge with increasing age(Reference Ventura and Worobey15). There is evidence suggesting that dairy products consumption decreases with age, from childhood into adolescence(Reference Dror and Allen9). Therefore, it is important to promote healthful eating, including dairy products consumption, throughout childhood; from the early years where lasting food preferences are developed into late childhood, where the number of exposures influencing food behaviour increases. Intervening prior to adolescence may be effective in preventing this decline in dairy products consumption and in allowing for the involvement of parents, while the direct role of parents in determining their children’s diets remains prominent.

Parents and familial environment have an important influence directly and indirectly on children’s food preferences and consumption(Reference Scaglioni, De Cosmi and Ciappolino16). As parents are often the main providers of food for children, they can directly affect the availability of healthful foods, but may also influence children’s behaviour through modelling(Reference Scaglioni, De Cosmi and Ciappolino16). The ways in which parents influence a child’s diet, which are commonly referred to in the literature, include (but are not limited to) parental knowledge, self-efficacy, attitudes and knowledge, socio-economic status and education level, motives for food choice, feeding style/parenting practices, role modelling and early life feeding, many of which may interconnect(Reference Scaglioni, De Cosmi and Ciappolino16–Reference Wardle18). Despite this important influence, just three interventions reviewed by Hendrie et al. included a parental or familial component(Reference Hendrie, Brindal and Baird12). Additionally, Srbely et al. recommend the inclusion of parents in preschool dairy products interventions(Reference Srbely, Janjua and Buchholz13). To consider parents’ inclusion in childhood dietary interventions promoting dairy products intake, the complex parental factors influencing children’s food consumption, and more specifically, dairy products consumption should be further understood.

Existing reviews on the factors affecting children’s diet examine parents’ influence on children’s overall diet quality and specifically fruit and vegetable, sugar-sweetened beverage and water consumption(Reference Mazarello Paes, Hesketh and O’Malley19–Reference Ong, Ullah and Magarey22). Within such reviews, a wide range of parent-related exposures were identified, including feeding practices, socio-demographic and home environmental factors. While similar factors were studied across each review, associations with children’s diet were unique to each food type. For example, positive parental modelling was positively associated with fruit and vegetable consumption and negatively associated with sugar-sweetened beverage consumption(Reference Mazarello Paes, Hesketh and O’Malley19,Reference Ong, Ullah and Magarey22) , but there was no evidence of association with water consumption in a review conducted by Franse et al. (Reference Franse, Wang and Constant21). This highlights the need for research on the determinants of dairy products consumption in isolation, to explore the unique influences on its consumption. To our knowledge, there is a lack of literature reviewing parents’ influence on dairy products consumption specifically. The aim of this review is to explore the parent-related determinants of dairy products consumption among 2–12-year-old children.

Methods

A narrative review of the literature was conducted. The literature search of the PubMed, Embase and psycINFO databases was conducted in October and November of 2020. This search was updated in January 2021. The search was limited to papers published in the years 2001 to 2021. The search terms used are outlined below (Table 1), relating to the population, exposure and outcome of interest.

Table 1 Search terms for literature search

Additional literature was identified through Google search and searching reference lists. The first author selected the papers to be included in the review, based on the following criteria, agreed upon by the authors: Studies conducted among children (aged 2–12) which investigated the influence of parent-related factors on milk or dairy products consumption were included. Articles were included if they were published in an academic journal, in English. All types of study design were considered, provided statistical significance was reported.

Data extraction

Extraction of key data on each study was conducted using an Excel spreadsheet. The data extracted included first author, year of publication, study design, population characteristics (sample size, age, gender, country), dairy products outcome, parent-related exposure and results. When consumption of dairy products was reported separately for each dairy product, milk, yogurt and cheese consumption alone were considered for inclusion in the review and not flavoured milks or milk-based desserts. Study quality was not examined due to the heterogeneity of the studies included.

Results

Overview of studies

The search yielded 631 unique articles for abstract and title screening (Fig. 1)(Reference Page, McKenzie and Bossuyt23), using the screening application, Rayyan(Reference Ouzzani, Hammady and Fedorowicz24). The full texts of 117 articles were subsequently screened. Twenty-five articles were selected for final inclusion in the review(Reference Asakura, Todoriki and Sasaki25–Reference Zahid, Davey and Reicks49). The most common reasons for exclusion of full texts were lack of data looking at the influences on dairy products consumption alone and populations outside of the age criteria.

Fig. 1 PRISMA Flow Diagram, detailing the search and manuscript screening conducted for the present review(Reference Page, McKenzie and Bossuyt23)

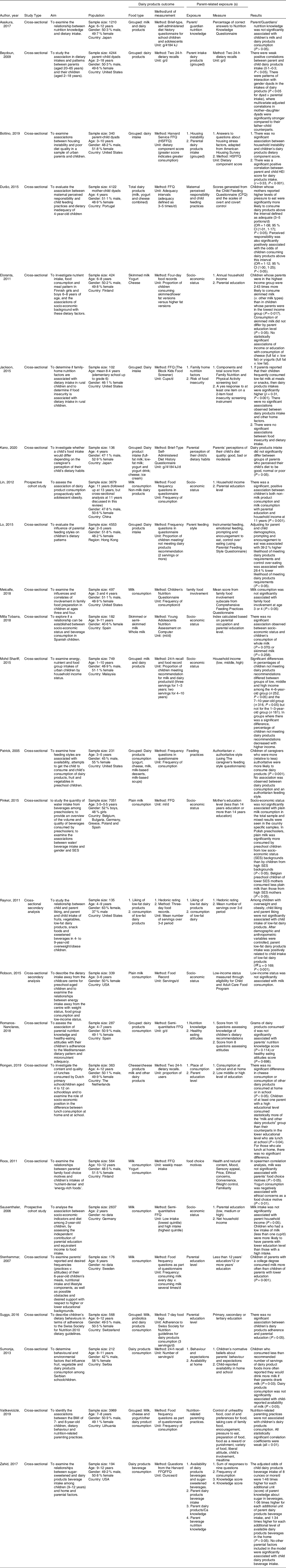

Eight studies were conducted among preschool-aged children (2–5 years), 11 were conducted among school aged-children (6–12 years) and six were conducted among children at varying stages of childhood (2–12 years). Fifteen studies examined the influence of parent-related factors on the total consumption of dairy products and 10 examined the parental influences on milk separately. Table 2 outlines the details of the reviewed studies, which will be discussed under the following headings: socio-economic status; availability, parent consumption, parent feeding practices; home food environment; beliefs and attitudes and parental knowledge.

Table 2 Characteristics of studies examining the factors influencing dairy products consumption

Socio-economic status

Twelve studies examined the influence of socio-economic status on children’s dairy products consumption(Reference Bottino, Fleegler and Cox27,Reference Eloranta, Lindi and Schwab29,Reference Jackson, Smit and Manore30,Reference Lin, Tarrant and Hui32,Reference Milla Tobarra, García Hermoso and Lahoz García35,Reference Mohd Shariff, Lin and Sariman36,Reference Pinket, De Craemer and Maes38,Reference Robson, Khoury and Kalkwarf40,Reference Rongen, van Kleef and Sanjaya42,Reference Sausenthaler, Kompauer and Mielck44–Reference Suggs, Della Bella and Marques-Vidal46) . Within the reviewed studies, socio-economic status was most commonly measured by parental education level or household income.

Four studies examined the association between socio-economic status and milk intake in preschool-aged children(Reference Mohd Shariff, Lin and Sariman36,Reference Pinket, De Craemer and Maes38,Reference Robson, Khoury and Kalkwarf40,Reference Sausenthaler, Kompauer and Mielck44) . No studies reported a significant association between household income and preschool children’s milk intake(Reference Mohd Shariff, Lin and Sariman36,Reference Robson, Khoury and Kalkwarf40,Reference Sausenthaler, Kompauer and Mielck44) , and mixed results were observed in relation to parent education level(Reference Pinket, De Craemer and Maes38,Reference Sausenthaler, Kompauer and Mielck44) . Sausenthaler et al. reported that in a cohort of 2637 2-year-olds, children who had a low intake of milk (less than one cup/d) were more likely to have parents with lower education level than those with a high intake(Reference Sausenthaler, Kompauer and Mielck44). In a large study among preschoolers from six European countries, parent education level was not significantly associated with milk consumption overall, but significant differences were observed at a country level(Reference Pinket, De Craemer and Maes38). Among Belgian preschool children, those whose parents had achieved a higher level of education had higher milk intakes (P < 0·05). Conversely, among Polish children, those with parents with a higher level of education had lower milk intakes (P < 0·05).

Nine studies reported data on the influence of socio-economic status on milk consumption(Reference Eloranta, Lindi and Schwab29,Reference Lin, Tarrant and Hui32,Reference Milla Tobarra, García Hermoso and Lahoz García35,Reference Stenhammar, Sarkadi and Edlund45) and dairy products consumption(Reference Bottino, Fleegler and Cox27,Reference Eloranta, Lindi and Schwab29,Reference Jackson, Smit and Manore30,Reference Lin, Tarrant and Hui32,Reference Mohd Shariff, Lin and Sariman36,Reference Rongen, van Kleef and Sanjaya42,Reference Suggs, Della Bella and Marques-Vidal46) among school-aged children. Milk consumption was significantly positively associated with either parental education level or household income in two studies (P < 0·05)(Reference Eloranta, Lindi and Schwab29,Reference Lin, Tarrant and Hui32,Reference Stenhammar, Sarkadi and Edlund45) . However, the socio-economic variable which was associated with milk consumption varied. The study conducted by Eloranta et al. reported that children with parents in the highest income group were more likely to consume skimmed milk, v. other milk types than children whose parents were in the lowest income group (P = 0·017)(Reference Eloranta, Lindi and Schwab29). In the same study, there was no significant association between parental education level and type of milk consumed by children (P > 0·05). Three out of seven studies examining the influence of socio-economic status on school-aged children’s dairy product consumption observed a positive association with parental education and/or household income(Reference Bottino, Fleegler and Cox27,Reference Lin, Tarrant and Hui32,Reference Mohd Shariff, Lin and Sariman36,Reference Rongen, van Kleef and Sanjaya42) . The remaining studies observed no association with measures of socio-economic status(Reference Bottino, Fleegler and Cox27,Reference Eloranta, Lindi and Schwab29,Reference Jackson, Smit and Manore30,Reference Suggs, Della Bella and Marques-Vidal46) .

Home availability

Two studies reported data on the influence of the availability of dairy products on consumption, both of which were conducted among school-aged children(Reference Sumonja and Novaković47,Reference Zahid, Davey and Reicks49) . Zahid et al. examined the influence of parental factors on 9–12-year-old children’s beverage consumption(Reference Zahid, Davey and Reicks49). Home availability of dairy products beverages (milk and cocoa made with milk) was positively associated with dairy products beverage intake (OR = 1·34; 95 % CI (1·03, 1·73); P = 0·03) and negatively associated with the availability of sugar-sweetened beverages (OR = 0·74; 95 % CI (0·53, 1·05); P = 0·09). Conversely, Sumonja et al. observed that child-reported home availability of dairy products was not significantly associated with dairy products consumption adequacy in a cohort of 8–11 year-olds (P > 0·05)(Reference Sumonja and Novaković47).

Parent consumption

Four studies examined the association between parents’ and children’s dairy products intake with that of their parents(Reference Beydoun and Wang26,Reference Bottino, Fleegler and Cox27,Reference Raynor, Van Walleghen and Osterholt39,Reference Zahid, Davey and Reicks49) . Zahid et al. reported that parent dairy products beverage intake specifically was associated with child dairy products beverage intake among 9–12-year-old children and their parents (OR = 1·06; 95 % CI (1·02, 1·10); P = 0·01)(Reference Zahid, Davey and Reicks49). Similarly, Bottino et al. observed a moderate correlation between parent and children’s Healthy Eating Index score for dairy products (r = 0·33, P < 0·001) and Raynor et al. reported that parent intake of low-fat dairy products was a significant predictor of children’s low-fat dairy product intake in a regression model (R 2Δ = 0·169, P < 0·001).

One of the mentioned studies was carried out among a representative sample of children from the USA, where Beydoun et al. reported a significant, weak correlation between parent and child dairy products consumption among 2–10-year-old children(Reference Beydoun and Wang26). When parent–child correlations were stratified by gender in the overall population (2–18 years, n 4244), correlations for dairy products consumption for mother–daughter dyads were significantly stronger than for father–child dyads. This difference in the influence of mothers and fathers is reflected in an analysis of questionnaires, completed by 8–11-year-old children(Reference Sumonja and Novaković47). Sumonja et al., reported a borderline significant trend, where children were more likely to meet their recommended daily dairy products intake if they reported that their mothers drank milk every day (OR = 8·56; 95 % CI (0·96, 76·25); P = 0·05)(Reference Sumonja and Novaković47). However, dairy products consumption was not associated with children’s perception of their father’s milk intake. Additionally, children who did not meet dairy products recommendations were more likely to report that they would drink milk if their parents drank milk (OR = 0·14; 95 % CI (0·35, 72·16); P = 0·03)(Reference Sumonja and Novaković47).

Parent feeding practices

Three studies reported the influence of parental feeding style on dairy products consumption among preschool children(Reference Durão, Andreozzi and Oliveira28,Reference Lo, Cheung and Lee33,Reference Patrick, Nicklas and Hughes37) and one study examined its influence among school-aged children(Reference Vaitkevičiūtė and Petrauskienė48). No association was observed in 7–8-year-old children(Reference Vaitkevičiūtė and Petrauskienė48). Overall, among preschool children, feeding practices pertaining to a more authoritative v. authoritarian parental feeding style were positively associated with children’s dairy products consumption. An analysis of feeding style questionnaires completed by 231 caregivers of 3–5-year-old children reported a significant positive association between dairy products feeding attempts and children’s dairy products consumption with a more authoritative feeding style (P < 0·01 and P < 0·001, respectively)(Reference Patrick, Nicklas and Hughes37). Adjusting for parent and child demographics, prompting and encouragement to eat was associated with 39·2 % higher likelihood of meeting dairy products requirements in a study by Lo et al. (Reference Lo, Cheung and Lee33).

The feeding practice ‘control over eating’ was not associated with dairy products consumption in a study by Durão et al. and was associated with a lower likelihood of children consuming two or more servings of dairy products/d in the study by Lo et al. (Reference Durão, Andreozzi and Oliveira28,Reference Lo, Cheung and Lee33) . Conversely, Durão et al. reported that the parent feeding style component ‘pressure to eat’ was associated with an increased likelihood of 4-year-old children consuming higher than the recommended servings of dairy products/d (>5 servings)(Reference Durão, Andreozzi and Oliveira28). Maternal perceived responsibility was also associated with children consuming dairy products above the recommended interval(Reference Durão, Andreozzi and Oliveira28).

Home food environment

Three studies assessed the influence of factors related to the home food environment on children’s dairy products intake(Reference Jackson, Smit and Manore30,Reference Metcalfe and Fiese34,Reference Vaitkevičiūtė and Petrauskienė48) . A study by Jackson et al. examined the association between dietary intake and a range of household factors among elementary school children residing in rural areas in the USA(Reference Jackson, Smit and Manore30). The family-home nutrition factors included meal patterns, eating habits, food and beverage choices, restriction and reward, family involvement, environment, screen time and routine. Overall, dairy products consumption was not significantly associated with family-related factors; however, children whose parents reported that their child drinks low-fat milk at meals or snacks had a higher dairy products intake (P < 0·001)(Reference Jackson, Smit and Manore30). Similarly, family involvement (involvement of children in food shopping and meal preparation) was not significantly associated with milk consumption in a cohort of children at ages 3 and 4 (P < 0·05) (n 497)(Reference Metcalfe and Fiese34). There was no correlation between 7- and 8-year-old children’s overall dairy products consumption and mealtime environment or children’s involvement in planning and preparing meals(Reference Vaitkevičiūtė and Petrauskienė48).

Parent beliefs and attitudes

Three studies examined the association between children’s dairy products consumption and parents’ attitudes, as measured through nutrition attitude score, perception of children’s diet quality and food choice motives, respectively(Reference Kano, Tani and Ochi31,Reference Romanos-Nanclares, Zazpe and Santiago41,Reference Roos, Lehto and Ray43) . In a cohort of Spanish 4–7-year-old children (n 287), parents’ nutrition attitude score was assessed through eight yes/no questions about parents’ attitudes to a list of nutrition statements; none of which were directly related to milk, yogurt or cheese(Reference Romanos-Nanclares, Zazpe and Santiago41). There was no significant association between parental nutrition attitude score and their children’s mean daily dairy products intake (P = 0·698)(Reference Romanos-Nanclares, Zazpe and Santiago41). Similarly, Kano et al. did not observe a significant association between parental perceptions and children’s daily consumption of dairy products (milk, yogurt, cheese and icecream) (P > 0·05)(Reference Kano, Tani and Ochi31). In this study, parental perception of their child’s diet quality was measured (good, poor or average quality) and its association with children’s actual dietary consumption was examined. Roos et al. examined the influence of parental family food choice motives on the dietary consumption of their 10–12-year-old children(Reference Roos, Lehto and Ray43). Milk consumption was not significantly correlated with food choice motives, but there was a significant, weak negative correlation between children’s yogurt consumption and ethical concerns as a family food choice motives(Reference Roos, Lehto and Ray43).

Parental knowledge

Three studies overall assessed the influence of parental knowledge and children’s dairy products intake. In two studies examining the influence of parents’ overall nutrition knowledge on dairy products consumption, there was no significant association observed (P > 0·05)(Reference Asakura, Todoriki and Sasaki25). Both studies used parents’ total score from a knowledge questionnaire to test for association with dietary factors. Parents of 6–12-year-old children completed an eighty-four-question nutrition questionnaire assessing awareness of nutrition recommendations, sources of nutrients, physiological function of nutrients and relationship between nutrition and health outcomes(Reference Asakura, Todoriki and Sasaki25). The second study assessed parents’ awareness of children’s recommendations for ten food groups, including dairy products(Reference Romanos-Nanclares, Zazpe and Santiago41).

One study examined the influence of parents’ dairy products and Ca knowledge specifically on 9- to 12-year-old children’s dairy products consumption(Reference Zahid, Davey and Reicks49). Parents’ knowledge of sugar in beverages was positively associated with children’s dairy products beverage intake (OR = 1·46; 95 % CI (1·06, 1·99); P = 0·02), whereas Ca/dairy products knowledge and general beverage nutrition knowledge were not related to children’s dairy products beverage intake (P > 0·05)(Reference Zahid, Davey and Reicks49).

Discussion

This review identified literature examining the influence of parental influence on the dairy products consumption of 2–12-year-old children under the sub-categories: socio-economic status, parental beliefs and knowledge, availability, home environment and parental feeding practices. It has highlighted gaps in the literature and provided direction for future study within these areas.

The influence of socio-economic status on children’s dairy products intake was examined more frequently than other variables within this review. Although the results are inconsistent, when significant associations were observed, they generally indicated that children with parents of higher socio-economic status had a higher dairy products consumption. This is consistent with previous research that reports an association between lower socio-economic status and poor diet quality(Reference Darmon and Drewnowski50), which is a valuable consideration when designing dietary interventions. However, further research is necessary on the modifiable parental factors potentially influencing children’s dairy products intake, such as availability, attitudes, knowledge and parental consumption for the identification of potential intervention targets.

There is little published on the influence of environment and availability on children’s dairy products consumption; however, the studies reviewed suggest that home environmental context (mealtime context, children’s involvement in meal preparation and planning) may be less influential than the social influence of parents on children’s dairy products consumption. While associations in some of the reviewed studies were weak, there clearly appears to be a relationship between parents’ dairy products-related dietary behaviours and their children’s behaviour, particularly the behaviour of their mother. Parent food modelling is a potential mechanism by which this may occur. Modelling has been shown to influence children’s sugar-sweetened beverage consumption, promote adequate fruit and vegetable consumption and involve parents physically eating foods in front of their child(Reference Mazarello Paes, Hesketh and O’Malley19,Reference Draxten, Fulkerson and Friend51) . Results from the study by Sumonja et al. support this idea, as it did not assess the correlation between parents’ and children’s diet directly, but demonstrated a borderline significant association between children’s dairy products consumption and their own perception of their parents’ dietary behaviour(Reference Sumonja and Novaković47). Additionally, children who did not meet dairy products recommendations were more likely to report that they would drink more milk if their parents also drank milk, suggesting that children in this cohort place value in their parents’ dietary behaviour. While further research is necessary on the link between parents’ and children’s dairy products consumption and its mediating factors, particularly in preschool-aged children, this research indicates that children’s dairy products consumption may be targeted through influencing parental dietary behaviour and promotion of positive food modelling.

Parents’ feeding style is a second interpersonal factor which may play a role in children’s dairy products consumption. The reviewed studies, conducted among preschool-age children, suggest that different parent feeding practices have differing effects on children’s dairy products consumption in this age group. An authoritarian feeding style incorporates practices that attempt to closely control what a child eats, whereas authoritative feeding offers the child a choice of foods and encouragement to eat, while allowing the child to make eating decisions(Reference Patrick, Nicklas and Hughes37). The results from the studies discussed indicate that, when allowed a certain level of autonomy over eating, preschool-aged children may be more likely choose to consume dairy products, which is consistent with literature surrounding children’s overall diet quality reporting that an authoritative feeding style generally promotes the healthiest dietary habits(Reference Kiefner-Burmeister and Hinman52).

The studies discussed suggest that feeding practices pertaining to a more authoritarian feeding style could potentially have a negative impact on children’s dairy products intake(Reference Durão, Andreozzi and Oliveira28,Reference Lo, Cheung and Lee33) . The study by Durão et al. demonstrated that pressuring a child to eat may contribute to overconsumption of dairy products. While adequate dairy products intake is important for growth and development, overconsumption may displace other foods in the diet. This is particularly relevant at this preschool age, where children have high nutritional requirements but low capacity for food intake(53). There is a need for clear public health messaging for parents around dairy products recommendations for children. Further research is necessary, particularly in school-aged children, to further assess the influence of differing parental feeding styles.

Nutrition knowledge and beliefs are known to play a role in shaping dietary behaviour; however, in this review, parental knowledge and attitudes were associated with children’s dairy products consumption in just two out of six studies(Reference Roos, Lehto and Ray43,Reference Zahid, Davey and Reicks49) . It is important to note that in a majority of studies discussed in this review, dairy products consumption was not the primary outcome or was examined in conjunction with several other dietary variables. Consequently, the data collection methods reflected this. All but one study assessing the influence of parental knowledge or attitudes assessed the influence of parents’ overall nutrition knowledge or beliefs regarding general diet quality, and not dairy products-related knowledge or beliefs exclusively. One study which measured parents’ attitudes towards a list of nutrition statements did not include an item directly related to milk, yogurt or cheese on the questionnaire(Reference Romanos-Nanclares, Zazpe and Santiago41). While it is valuable to assess parents’ general nutrition knowledge and healthy eating attitudes on their child’s dairy products consumption, it is necessary to further explore perceptions around dairy products specifically, in order to identify potential targets for dairy products interventions and to truly understand if attitudes and knowledge influence children’s dairy products intake.

Overall, this review identifies a need for more specificity when examining the influences on children’s dairy products consumption. Fifteen studies measured dairy products intake as a total score or pooled intake of several dairy products, many of which do not clearly state which dairy products are incorporated in this total. In three studies, this outcome measure included products such as milk-based desserts and flavoured milk(Reference Kano, Tani and Ochi31,Reference Patrick, Nicklas and Hughes37,Reference Vaitkevičiūtė and Petrauskienė48) , consumption of which is not recommended at the same level as the consumption of milk, yogurt or cheese. While these products are categorised under the same food group, they differ in taste, culinary use and nutritional value in terms of sugar and fat content. Therefore, examining the influences on milk, yogurt and cheese intake individually may be more appropriate. Furthermore, as children’s milk consumption is decreasing(Reference Dror and Allen9), further research should be carried out on the determinants of its consumption alone. Ten studies within this review considered milk consumption individually, six of which examined milk consumption according to measures of socio-economic status only. This identifies a gap in the literature looking at the influence of modifiable factors on children’s milk consumption.

Limitations

A limitation of this literature review is the age limit set, as part of the inclusion criteria. While research conducted among adolescents was beyond the scope of this review, the age cut-off of 12 years resulted in the loss of potentially valuable data in cases where children aged older than 13 or older were included within a child sample, and data were not presented separately.

The subject area examined is broad and the reviewed studies assessed a range of parental factors and their influence on children’s dairy products consumption, which were categorised under several headings. However, there is little published within each category. There is also heterogeneity within some categories discussed, particularly in how parental attitudes and knowledge were measured. Therefore, conclusions cannot be drawn based on the limited number of studies within each category and heterogenous nature in which outcomes and exposures were measured.

Study design and methodological aspects of the studies reviewed posed several limitations. The lack of consistency in the measurement and reporting dairy products consumption does not allow for direct comparison between studies. Some studies reported average consumption of milk and individual dairy products, while others reported grouped consumption of dairy products or dairy consumption scores. As fifteen studies reported children’s total dairy products consumption, it is difficult to determine the influences on individual types of dairy products. Furthermore, most studies reviewed were cross-sectional in design, lacking the ability to demonstrate the temporal nature of parental influences.

Previous literature has shown that parental influence on children’s general diet quality can differ between parents’ gender(Reference Scaglioni, De Cosmi and Ciappolino16). Two of the studies reviewed suggested a difference in the influence of mother’s and father’s consumption on children’s dairy consumption(Reference Beydoun and Wang26,Reference Sumonja and Novaković47) . However, all but one study reviewed, which reported the gender of responding parents, had parental populations primarily comprised of mothers or female caregivers. Inclusion of fathers or male caregivers in future analyses is necessary to further explore their influence on children’s dairy products consumption and to identify differences between the influence of mothers and fathers.

Conclusion

A range of parental factors have been discussed in relation to children’s dairy products consumption; however, little is published within each category of parental influence. Further research is needed on the influence of modifiable parental factors, particularly on children’s milk consumption specifically, to identify potential intervention targets. Due to the limited number of studies conducted on modifiable parental factors and the heterogeneity of the studies reviewed, it is difficult to draw conclusions. However, it appears from the limited number of studies available that social influences such as parent feeding practices and parent consumption of dairy products, may have an influence on children’s dairy products consumption. Further research is necessary on the influence of parents on children’s consumption of individual dairy products and on the interaction between these factors in influencing children’s dairy products consumption.

Acknowledgements

Acknowledgements: None. Authorship: E.G.: design of the review; conducting search of literature; data extraction; drafting the paper. C.M.: conception of study design; Advising on design of the review; revision of the article; final approval. Ethics of human subject participation: Not applicable.

Financial support:

PhD funding for the first author: Department of Agriculture, Food and the Marine. V1472 – Evaluation of the EU School Scheme.

Conflicts of interest:

There are no conflicts of interest.