Along with brooches and hairpins, finger rings are among the most common of Roman dress accessories. A group of 24 bronze rings, found threaded onto a bracelet in the vicus at Wareswald (the “Forbidden Forest”) in 2018, provides rare evidence for the production of rings at the very lowest end of Roman finger fashion. A study of the group alongside related finds shows that it consists of the products of a craftsman who was active in the vicus in the early 4th c. CE. Despite their provincial and non-elite rural context, the rings followed global Roman fashion trends closely and circulated over surprisingly large distances.

The role of Roman personal adornments, and signet rings in particular, as indicators of identity, has been the topic of several recent studies.Footnote 1 The analysis of the Wareswald find affords the opportunity to discuss the function and meaning of low-value “trinket” rings, which, like their more valuable counterparts, could also make statements about their owners’ identities. While some rings may have indicated local and regional affiliations, they were probably not part of a dialogue about “Roman” and “native,” but could stress other aspects of identity, such as literacy, marital status, or membership in a particular group. The enormous popularity of these trinket rings was due to their ability to provide poorer individuals with the feeling that they were participating in the fashionable lifestyles of the upper classes.

The Roman vicus at Wareswald (the “Forbidden Forest”)

The archaeological site known as Wareswald is located about 2 km to the east of the village of Tholey in the Saarland, Germany. The site was a small settlement (vicus) in the province of Gallia Belgica, in the former tribal territory of the Celtic Treveri and located 41 km to the south of Trier (Augusta Treverorum). The vicus was situated at an important intersection of roads that connected Metz (Divodurum) with Mainz (Mogontiacum), and Trier with Strasbourg (Argentoratum). Thus, Wareswald was likely both a stopping point for travelers and a commercial center for the surrounding region.

The name “Wareswald” is not ancient but may have been derived from the Middle High German verb wern – modern German verbieten – “to forbid,” and thus can be translated “Forbidden Forest.” It likely dates to the medieval period, when ordinary people were prohibited from hunting, felling wood, or otherwise making use of the forest that had grown over the vicus.Footnote 2 Finds of Roman objects and structures are attested as early as 1755, and the site was regularly plundered for both building material and antiquities through the 19th and 20th c.Footnote 3

Today, Wareswald is a nature and archaeological preserve, and it has been the subject of regular excavations by the non-profit archaeological company Terrex since 2001. The goals of these excavations are to better understand the Roman settlement, and its relation to local and regional history, and also to transform the site into an open-air museum.Footnote 4 Since 2018, the German team, directed by Klaus-Peter Henz, has been joined by Philip Kiernan and a team of students from Kennesaw State University. This publication represents the first fruits of this new collaboration.

The Terrex excavations have concentrated on four areas. The first exposed a series of conjoined houses that faced the settlement's main street and shared a covered walkway that ran alongside it. As in other Roman vici, these structures doubled as workshops, businesses, and stores. They underwent numerous renovations, such that their interpretation is now difficult, but they include rooms with hypocaust heating, cellars, and in one case, a bath.Footnote 5 It is likely that much of the settlement was composed of similar houses. In the southwest of the settlement, a large Romano-Celtic temple has been fully excavated. Bronze statuettes and spearheads found there suggest the temple was dedicated to Mars, the principal divinity of the Treveri.Footnote 6 Halfway between the temple and settlement areas is a large building with a central courtyard and cellars. Whether it was the residence of a wealthier family or served a communal function, for example, as a mansio, is unknown. Finally, on the westernmost edge of the site, sculptural fragments and the foundations for at least one tower-like funerary monument were uncovered in 2006. The monument dates to the 2nd c. CE and is similar in form to the famous tomb of the Secundinii at Igel.Footnote 7 A single burial of the La Tène C2 period (200–150 BCE) was unearthed below the Mars temple. Along with occasional pottery sherds of the later Iron Age, it suggests a pre-Roman occupation about which little is known.Footnote 8 Coin finds indicate that the Roman occupation began in the early 1st c. CE and continued until the late 4th.

Discovery and context of the Forbidden Forest rings

On 18 June 2018, volunteer excavators uncovered many small pieces of bronze next to a wall in the settlement area.Footnote 9 A closer examination quickly revealed that numerous finger-rings were present in the soil, apparently threaded onto a twisted piece of bronze wire (Fig. 1).

Fig. 1. The rings at the moment of their discovery. To the right, a large iron nail. (Photo by K.-P. Henz.)

The rings were found in a corridor that led off a courtyard between Structure D and the largely unexcavated and badly disturbed Structure E (Fig. 2). To the south, the courtyard was bordered by a large cellar, while small rooms on the southeast side of structure D likely served as workshops or storage spaces. The rings were found next to a wall (Fig. 3) in a typical fill layer that likely formed the surface upon which the final inhabitants of the vicus walked. No datable sherds or other remarkable finds were recovered in this layer, save a large iron nail (visible in Fig. 1), which is typical of the sort of habitation detritus these fill layers contain.

Fig. 2. The main excavated area of the vicus and findspot of the rings. (Plan courtesy Terrex gGmbh.)

Fig. 3. Excavation photo of the findspot of the rings (marked by the dot), with the pit (Fst. 1495) in the course of being excavated. (Photo by K.-P. Henz.)

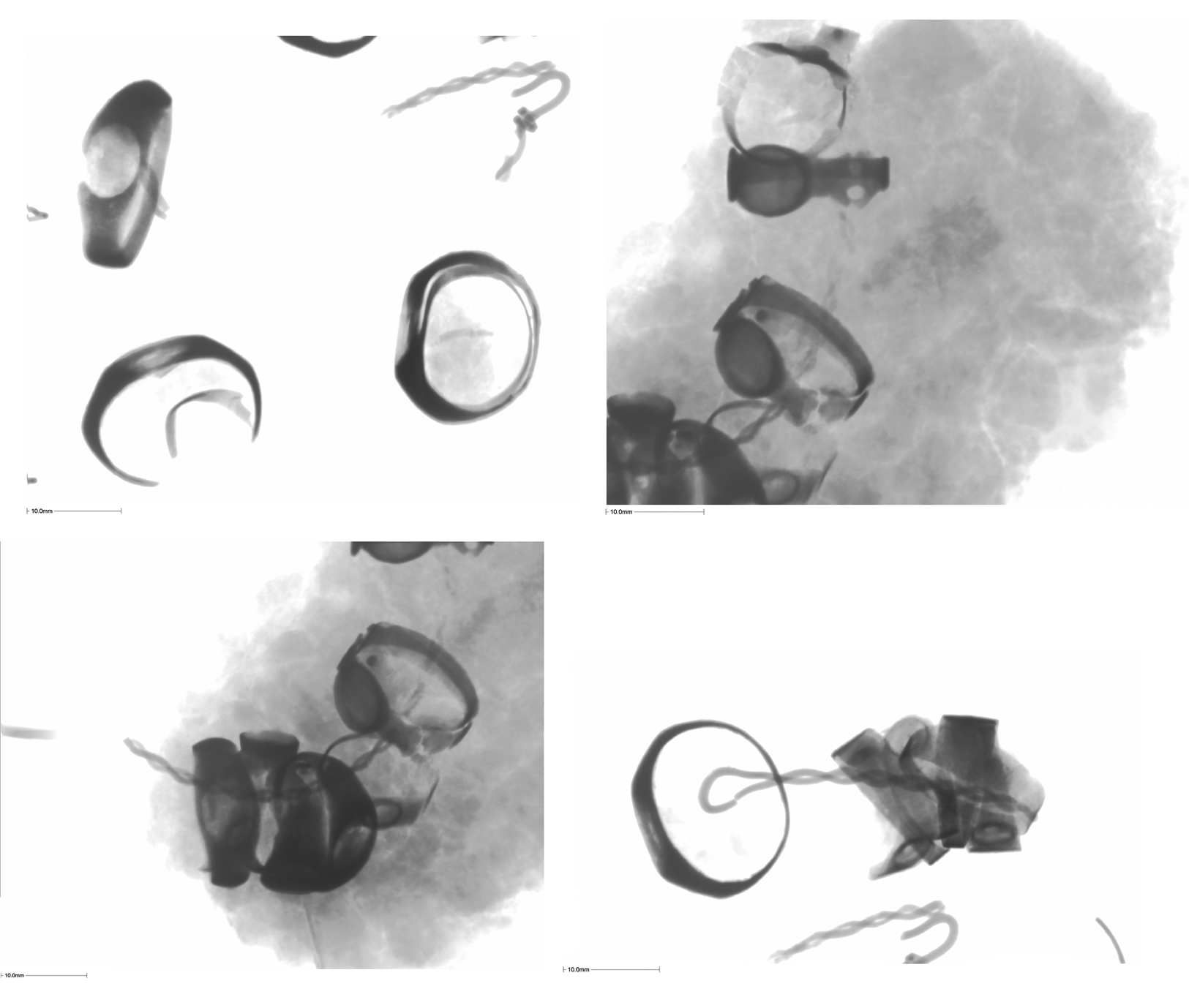

Given the delicacy of the find, it was lifted in a single block, x-rayed (Fig. 4) and excavated in the conservation laboratory of the State Archaeological Service of the Saarland. The block contained a further 19 rings, all of which had originally been strung onto two pieces of twisted copper wire.

Fig. 4. Details from X-Rays of the excavated block prior to conservation. The rings can be seen threaded onto the wire bracelet. (Photo by Nicole Kasparek; courtesy Landesdenkmalamt Saarland.)

On 11 July 2018, another ring was found, in the upper part of a shallow pit that otherwise contained only stones and tile fragments. This pit had been dug into the fill layer less than a meter to the east of the findspot of the group of rings.Footnote 10 Whether this ring (no. 24) was originally part of the group or was a later, unrelated loss is unclear.

The context of the finds contributes little to their dating and interpretation. The rings were discovered near buildings that served as habitations but in which artisan and commercial activities also took place. They were not part of a structured deposit, such as a hoard or votive deposit. Instead, they entered the ground as part of a fill layer, or else were a casual loss that was somehow mixed into the fill later.

Description of the rings

The scant information provided by the archaeological context is supplemented by the very rich internal evidence of the objects themselves (Fig. 5). A full descriptive catalogue with a typological and comparative study is provided in the Supplementary Materials. The results are summarized here.

Fig. 5. The Wareswald ring group. Front to back rows: bracelet, ring types 1, 2, 3 and 5, 4. (Photo by Josef Bohnenberger)

The piece of wire onto which the rings had been threaded is in fact a cable bracelet, a dress accessory commonly found in female burials of the first half of the 4th c. CE (see Fig. 9A–B). The 24 rings can be divided into five distinct types. Within each, the rings are all virtually identical (Fig. 6).

Fig. 6. Ring types from the Forbidden Forest group, with widest probable date ranges and placement in typologies. The number in each segment of the chart indicates how many rings of this type are in that group. (Drawing by Carmen Keßler.)

The first type consists of rings set with glass nicolo gems (Suppl. Figs. 1 and 2). Bronze rings of this exact form, often with this same sort of glass nicolo, are extremely common across Gaul, Germany, and Britain, and are usually dated between 200 and 250 CE, or perhaps later. The form is derived from 1st-c. CE types, and it is also known in gold and silver (Fig. 8A–B). The glass nicolos were produced in workshops in either Trier or Cologne. They are poorly preserved, and the intaglios of only three can be identified with certainty: Hercules wrestling the Nemean Lion, a seated Vulcan or perhaps Daedalus, and a lion (Fig. 7).

Fig. 7. Magnified views of the three identifiable glass nicolos. Numbers correspond to the catalogue in the Supplementary Materials. (Sabine Brygadin; courtesy Landesdenkmalamt Saarland.)

On the Type 2 rings (Suppl. Fig. 3), a small blob of molten glass was pressed into a circular chaton, creating a plain gem with a waved surface. Below each gem, a small perforation and raised burr of metal were created when air trapped below the hot glass escaped through the hoop. The fact that these burrs were never filed off suggests that the rings were not finished. Similar bronze rings from northern and eastern France, as well as from Britain, mostly date to the first half of the 4th c. CE. The type imitates expensive gold and silver rings with raised chatons or with chatons that were made separately and soldered onto the hoop (Figs. 8F–G and 10).

Fig. 8. Gold and Silver Rings in the British Museum. A) 1850,0601.7, from the Backworth Hoard; B) AF.428, found in River Witham, Bardney; C) AF.208, inscribed AMA ME, found in Carlisle in 1860; D) 1917,0501.541, ex Wollaston Franks; E) 1900,1123.2, from the Sully Moors Hoard; F) 1917,0501.824, ex Wollaston Franks; G) 1872.0604.338, ex Castellani. (Photos: © The Trustees of the British Museum.)

The Type 3 rings (Suppl. Fig. 5) have empty cavities for gems and distinctive diamond-shaped shoulders with perforations. They imitate gold rings with opus interrasile shoulders that appeared in the mid-3rd c. (Fig. 8D–E). Bronze rings from Carnuntum, Niederberg (Suppl. Fig. 6), Xanten, and Avenches are so similar that they must be from the same workshop. The Avenches, Carnuntum, and Xanten rings have glass nicolos like the Wareswald Type 1 rings, with which Type 3 is probably contemporary.

The Type 4 rings (Suppl. Fig. 7) are all unfinished. They are similar in shape to Type 3, but in place of a chaton, there is a simple cylindrical protrusion – the remains of a casting sprue destined to be filed off in a later stage of production. Once the rings were complete, short inscriptions and simple patterns could be stamped onto the bezel. Similar inscription rings (Fig. 8B and Suppl. Fig. 8C–D) date to the first half of the 4th c. CE.

The Type 5 rings (Suppl. Fig. 9) are octagonal, a form that was particularly popular in the Constantinian period. Unlike the other types, the two rings in this category are not identical, and it is possible that one (no. 24), found apart from the main group, is not related to the group.

Gender: rings for men, women, or children

The size of rings can indicate for whom they were intended. Internal diameters between 16.8 and 17.5 mm are usually considered average for adult female rings, and from 18.8 to 19.4 mm for adult male rings. Rings with diameters below 14 mm were likely meant for children.Footnote 11 The Wareswald rings are between 16 and 17 mm, which strongly suggests that they were intended for women, like the bracelet on which they were found threaded. Only the octagonal ring 23 (diam. 18.5 mm) approaches the range considered typical for men. This observation comes with some important caveats. First, these average diameters represent only higher probabilities that rings were intended for wearers of a particular age or sex. The real finger sizes of groups in any population overlap, such that measurements for some individual males, females, and children can fall within the size range of one of the other groups. In addition, though rings were mostly worn below the knuckle on the fourth and fifth fingers, anecdotal textual references and representations in artworks show that rings could be worn on any finger and sometimes, albeit rarely, on the upper two segments of fingers.Footnote 12 Finally, Roman definitions of “child” and “adult” differ from our own, making it harder to attach sex- and age-related categories to rings.

Past attempts to identify specific male and female ring types have mostly concluded that virtually all forms of ring could be worn by both sexes. The same point has been made about images on seal-stones and engraved bezels, where we might also expect a preference for particular motifs depending on the sex and age of the owner.Footnote 13 Ellen Swift, however, has recently shown that some motifs are more common on rings of sizes associated with men, women, or children. These include two motifs found in the Wareswald gems, lions and Hercules, which are associated with male-sized rings.Footnote 14 Again, these observations represent probabilities not certainties. The presence of typically male motifs on the apparently female-sized rings from Wareswald is not necessarily unusual. The lion, for example, could serve both sexes as a zodiac birth-sign. Older gems could also be re-used in newer rings, and as will be discussed below, by the late 3rd c. CE, the images engraved on gems were less important than they had been in the past.

Comparable finds: evidence for the use, trade and production of rings

The Wareswald rings add to the very scant archaeological evidence available for the use, sale, and production of rings in the Roman world. Some related finds are described below to help interpret the new finds, to illustrate Roman ring use, and so to set the stage for the discussion of rings and trinket rings that follows.

Rings as personal possessions: the Rennes Hoard and rings in graves

The most obvious interpretation of the Wareswald group would be as the lost jewelry of an individual. It seems to have been a common practice to thread rings onto a bracelet, or length of string, when they were not being worn, and individuals could also own multiple rings. Both points are illustrated by a hoard of silver coins and jewelry found in two amphorae in Rennes in 1881. The coins consisted of 16,000 denarii and antoniniani, suggesting a date of deposition in the early 280s. The hoard also included five spoons (four silver, one bronze), two silver bracelets, and a bracelet of twisted bronze wire. Nine silver rings had been threaded onto one of the bracelets (we do not know which), and three more silver rings were found loose in the hoard.Footnote 15

The pattern of ring forms in the Rennes Hoard is similar to that of the Wareswald group. Four have a raised chaton soldered onto the body, into which glass nicolos had been set. A fifth ring was set with a denarius of Antoninus Pius and another with a plain, circular black stone. Three rings have raised oval plates with inscriptions, IVLII, AM, and MEI, while a fourth was crudely inscribed IID on a wide flat bezel. Finally, the hoard included a plain circular ring and octagonal one.Footnote 16 Thus, the same visual elements as found in the Wareswald group are present: glass nicolos, a plain circular black gem, rings with steep decorated shoulders, inscriptions, and an octagonal ring. The Rennes rings must represent roughly the same period in ring fashion.

The 12 rings in the Rennes Hoard fall into at least eight types, making it more diverse in composition than the Wareswald group. Moreover, even within the hoard's most homogenous group, rings with glass nicolos, no two rings are completely identical. Several rings show signs of wear, and none are unfinished. These were the functional rings of an individual who had acquired them over time and from multiple sources. Being made of silver, like the coins they were found with, the Rennes rings were both a form of personal adornment and a store of wealth. The material value of the Wareswald rings was minimal.

The rings of poorer individuals are illustrated by a number of burials, including some where they were threaded onto bracelets and string. A simple ring of bronze wire and another with a circular bezel engraved with a depiction of a snake were found attached to a cable bracelet in a burial at Künzing (Fig. 9B).Footnote 17 It is not impossible that the rings were sometimes worn like this, instead of on the finger. Another cable bracelet from a grave at Colchester (Fig. 9A) had a blue glass bead and a bronze bell attached to it, suggesting that bracelets were sometimes enhanced with decorative pendants.Footnote 18 Both burials date to the 4th c. CE. The grave of a child, aged 10 or 11, found at Healam Bridge (North Yorkshire) included six bronze rings fused together in a position that suggested they had once been threaded onto a piece of string (Fig. 9C). All six rings are very similar in design, and most contain traces of a blue enamel in their bezels. Unlike the Wareswald rings, however, there are variations in both the size and the design of each ring.Footnote 19

Fig. 9. A: Child-sized bracelet with bell and glass bead from Colchester (after Crummy Reference Crummy1983, fig. 41); B: Twisted wire bracelet from Künzing with two rings (after Keller Reference Keller1971, pl. 50); C: Rings from a child's grave at Healam Bridge (after Drinkall Reference Drinkall, Ambrey, Fell, Fraser, Ross, Speed and Wood2017, fig. 219). All scale 1:1. (Courtesy of the Colchester Archaeological Trust; Bayerische Akademie der Wissenschaften; Ecus Ltd.)

Both rich and poor could own multiple rings, which raises the question of whether they were sometimes worn in sets or specific configurations. The habit of threading rings onto a bracelet was also employed by rich and poor alike, and both could own multiple examples of very similar rings. But it was not usual to have multiple rings that were absolutely identical, and certainly not to have multiple unfinished rings. For these reasons, the new find cannot be interpreted as personal jewelry.

The jewelry business: retail (Bonn 1902) and wholesale (Trier 1989) finds

Two fortuitous discoveries in Bonn and Trier shed light on the ring trade in Gaul and Germany and allow us to explore the possibility that the Wareswald rings were the lost stock of a merchant.

During the construction of a new hospital in Bonn in 1902, a large assemblage of Roman objects, including more than 100 rings, as well as coins of Gratian and Valens, was found in a thick layer of ash. Most of the finds were taken by the workers and later acquired by the Landesmuseum in Bonn. The discovery was interpreted as the inventory of a store that sold jewelry and trinkets in the settlement just outside the ancient town's legionary fortress.Footnote 20

Rings must have been one of the store's best-selling products and were available in jet, glass, bronze, and iron.Footnote 21 The find also included 19 loose glass nicolos like those in the Wareswald rings.Footnote 22 But only two rings were actually set with nicolos: a bronze and an iron ring like the Type 1 rings from Wareswald. Yet another iron ring had an empty depression for a gem.Footnote 23 Several dozen plain bronze rings were found corroded together, giving the impression that they had been kept threaded on a string.Footnote 24 The most numerous and distinctive rings, however, were 55 bronze rings bearing short inscriptions (Suppl. Fig. 8D). These are similar to the Wareswald Type 4 rings, which may have been destined to receive similar inscriptions.Footnote 25

Though poorly documented, the Bonn group has several elements that connect it to the Wareswald find: glass nicolos, multiple identical rings, octagonal rings, and rings with inscriptions. The coins associated with the Bonn assemblage and the spellings used in some of the inscriptions suggest they were lost in the third quarter of the 4th c. CE.Footnote 26 If this is correct, then there was a gap between the store's glass nicolos and the inscription rings that was much like the chronological divide in the Wareswald group.

Perhaps the glass gems were old stock or were kept to repair heirloom rings brought in by soldiers and civilians in Bonn. It is significant that while the find included unset gems, there were few rings with sockets in which to mount them. Besides the one ring missing a gem, the rings at Bonn all seem to have been finished and ready to sell. There are no obvious signs that the rings were still in production. While the store sold rings of an equally low quality to those found in Wareswald, it also offered more costly rings of jet and glass. Even in its twilight years, Bonn probably contained a much greater range of wealth than the small rural vicus.

During excavations of the Viehmarkt in Trier in 1987, 80 bronze rings were found corroded together in several groups that suggested they had once been threaded onto organic strings. The glass gems set into the rings have been published by Antje Krug, though full details of the find circumstances, which suggest a date of deposition in the Flavian period, have not.Footnote 27 The rings in the hoard were identical in form, each holding a blue or green glass gem set flush with the top of the ring. The intaglios depict a range of subjects, including the busts of mythological figures, theatrical masks, and animals. Many of the motifs are repeated in several exact replicas. The workshop that produced these gems likely made its molds from a collection of gems that had been cut by the same engraver in the early 1st c. CE.Footnote 28

While the Trier-Viehmarkt rings are of higher quality than the Wareswald rings, Krug still interpreted them as cheap products meant for the lower end of the market. The gems are mass-produced casts, and the rings themselves are relatively thin bronze. The rings were fresh out of the final stages of production and ready to be sold wholesale to dealers or perhaps traveling peddlers.

It is possible that the Wareswald group represents a position further along the chain of production and distribution of mass-produced rings. Perhaps its owner had acquired several types from large workshops in Trier and was selling them in the countryside. But neither the Bonn nor Trier groups include unfinished rings; these wholesale products were ready to wear.

Roman ring production: the Snettisham Jeweler's Hoard

Presumably any goldsmith or metal worker could make rings, but a guild (collegium) of ring makers (anularii) existed in Rome, indicating that some craftsmen specialized in rings.Footnote 29 In the 3rd c. CE, an individual describing himself as an anularius dedicated an altar to Mars and Victoria in Mainz, the provincial capital perhaps being large enough to sustain specialized craftsmen.Footnote 30 Henkel imagined the anularii producing rings that were then sold by jewelers and merchants, and this seems to fit the picture of wholesale distribution seen in Trier.Footnote 31 Bronze ring production has been postulated at the much larger vicus at Dalheim (Riccacium, Luxembourg) on the basis of identical and incomplete rings found at the site, but more concrete archaeological evidence is almost non-existent.Footnote 32

Apart from the Wareswald group, a hoard of rings, coins, and other pieces of jewelry discovered in Snettisham (Norfolk) is the only other known find that attests to the production of Roman rings. The hoard was found in 1985 during construction work, then acquired by the British Museum and carefully studied. It was contained in a small ceramic vessel and included 110 bronze and silver coins, the latest of which was issued in 154/5 CE.Footnote 33 Apart from the coins, which may have been a source of raw material, all of the objects in the Snettisham hoard are connected with the activities of a craftsman producing personal adornments: small silver bars and ingots, pieces of scrap silver, and both finished and unfinished necklaces, bracelets, and rings. A quartzite blade in the hoard had been used for burnishing the surfaces of silver objects. Like the Rennes Hoard, these objects had presumably been hidden for later retrieval.

The hoard contained 75 complete silver rings, pieces of several others, and 117 carnelian gemstones engraved with intaglios. While the hoard also included pieces of wire and bracelets, there is no evidence that the rings had been threaded onto them. Scraps of cloth and a single seal box suggest that certain objects had been kept in a sealed bag.Footnote 34

The rings of the Snettisham Hoard are all silver. They fall into six distinct types, within which the individual examples are so very similar that they must have been produced in the same workshop.Footnote 35 The ring forms differ from the Wareswald group and represent an earlier period in ring fashion. The gems had been carved by two or three artists and were kept as stock for new rings or for setting into damaged rings that clients brought in for repair.Footnote 36

While the Snettisham hoard is a structured deposit, not a casual loss, it has much in common with the Wareswald rings. Both groups include finished and obviously incomplete rings, and a similar number of types. Where the Wareswald craftsman used bronze and mass-produced glass gems, the Snettisham jeweler worked in silver and with real engraved gems. Like the Snettisham Hoard, the Wareswald rings were the stock of the craftsman who made them, an artisan who catered to less affluent clientele than his earlier British counterpart.

The ring-maker at Wareswald: a local craftsman with global awareness

Though individuals and traders also kept rings threaded onto bracelets, the unfinished and identical pieces in the Wareswald group point firmly to the collection belonging to the craftsman who made them. We may add jewelry production to the short list of industries known to have taken place in Wareswald. The form of the rings (Types 2, 3, and 5) belongs to the first half of the 4th c. CE, though two types (1 and 4) are mid- to late 3rd c., and a date of deposition for the group in the first quarter of the 4th c. is probable.

Like the Snettisham jeweler, the Wareswald ring-maker had a repertoire of five different types, and perhaps finished rings by setting glass gems, or by adding inscriptions, according to the specifications of individual clients. The glass nicolos, likely made in Cologne or Trier, are the only element of the rings not produced in Wareswald. This suggests an interesting network in which jewelry components were exported from cities and finished up in rural workshops. The presence of a ring made in Wareswald as far away as Carnuntum (Pannonia) is a remarkable testimony to the reach of this small-town craftsman. Rings seem to be an unexploited source of information on trade patterns and mobility in the Roman Empire.Footnote 37

In her discussion of the Snettisham Hoard, Johns suggested that it is in the poorly studied low end of Roman jewelry that the most distinctively regional and local styles should be found.Footnote 38 That does not seem to be the case in Wareswald. Though his products were flimsy and cheap, the Wareswald jeweler knew what the most expensive jewelry of the day looked like and strove to imitate it. Presumably the buyers also had clear expectations of what rings ought to look like. Where did this local awareness of imperial fashion come from?

Expensive rings might have been seen on the fingers of travelers passing through the vicus, and the inhabitants of Wareswald likely traveled too. Some may have served in the army and thus been exposed to Roman fashion there. Local elites, notably the owners of the villas that surrounded the vicus, could certainly afford expensive rings. Nineteenth-century finds from Wareswald included rings of jet, glass, and gold, and an iron ring set with a true nicolo engraved with a satyr.Footnote 39 In 1987, excavations in Tholey-Schweichhauserstraße, 3 km to the west, produced a very fine gold ring with a filigree hoop and an elaborate chaton set with a red carnelian bearing a depiction of Mars (Fig. 10).Footnote 40 The ring is a distant variant of those that inspired the Type 2 rings. In short, luxury rings could be seen in the vicus, even if they were unaffordable for most of its inhabitants.

Fig. 10. A gold ring found at Tholey Schweichhauserstraße in 1987. (Museum für Vor- und Frühgeschichte Saarbrücken.)

To understand why such rings were produced and sold in the vicus, and what their purchasers wanted them for, we must place the Wareswald rings within a broader discussion of the function and meaning of low-value Roman rings.

Discussion: the function and meaning of Roman “trinket” rings

The Wareswald rings belong to a class of light, flimsy bronze rings that make up the vast majority of Roman rings, but to which very little attention has been given.Footnote 41 Martin Henig described them as “trinket rings,” and while the name implies that they were of little importance, it is wrong to assume they were devoid of either function or meaning.Footnote 42 Like all pieces of jewelry, they not only had specific uses, but also potentially made serious statements about the wearer's identity and aspirations.

The function of Roman rings

Both expensive and cheap Roman rings served a wide variety of functions, from wedding bands to protective amulets. Rings made excellent gifts and were sometimes awarded by the emperor to faithful soldiers and administrators, or exchanged between friends, family members, and lovers.Footnote 43 If the Type 4 rings from Wareswald were inscribed with love messages and greetings, like their counterparts from Bonn, then they were meant to be gifts.

Rings set with engraved gems could be used to make seals. The intaglio was pushed into a blob of wax or clay to create a recognizable and personal mark. Wax impressions were sometimes protected from damage in a bronze seal box through which cords also passed. The cords could then bind a wax writing tablet shut, or surround a box, a bag of coins, or some other container of valuables, such that these items could not be tampered with without breaking the seal.Footnote 44

Only the Type 1 and (when complete) Type 3 rings from Wareswald could have served this purpose, and both imitate ring forms into which real intaglio gems were often set. Like many other similar trinket rings, the Wareswald rings were set with glass nicolos. It is unlikely that these glass gems were ever meant to be used as seal-stones, since their mass-produced designs could never represent the unique symbols of an individual. This point is underscored by the fact that multiple identical glass gems can still be found today, and two of the Wareswald nicolos are replicas of four gems found elsewhere.Footnote 45 Moreover, the intaglios of many glass nicolos were not completely formed in the casting process, but such defective gems can still be found set into rings.

The acceptability of such replicated and low-quality glass gems probably had something to do with a change in the function of rings in Late Antiquity. Platz-Horster has argued that the custom of making seals with engraved gemstones came to an end, or had at least become very uncommon, by the late 3rd c. CE. This observation was based partly on the decreased production of intaglio gems, but also on the independent evidence of seal boxes, which disappear around 280. By the early 4th c. CE, rings with engraved metal plates and rings with plain unengraved stones, glass, and enamel encrustations became the new norm.Footnote 46

After the widespread practice of sealing had ended, earlier rings with intaglio gems continued to be worn, might lose their gems, and so require repairs. Thus, glass gems like those from the Wareswald can also be found in expensive gold and silver rings (for example, in the Rennes Hoard), where real gemstones would have been more appropriate. Older gems can also be found reset in 4th-c. CE jewelry with little or no attention to the orientation of their designs, suggesting that the stones were valued more for their color than for their motifs.Footnote 47 The Type 1 and 3 rings from Wareswald, and the loose glass nicolos in the Bonn find, were probably old, leftover stock, or rings that catered to old-fashioned tastes.

At the time when the latest rings in the Wareswald hoard were made, intaglio gems were something of an archaic feature – an attribute that consumers expected to be present in certain rings. They were the equivalents of the small square pockets that are still found in blue jeans and waistcoats today, which stem from a bygone age of pocket-watches. These gems were a pseudo-functional feature of the ring and not so much needed for their intaglio images. Still, the purchasers of the Wareswald rings had a choice of several different images, and their choices may have meant something to them and said something to others.

Even when trinket rings have no easily discernable practical use, we may speculate on functions beyond the purely decorative, based on their formal characteristics. For example, the textured surfaces of the gems in the Wareswald Type 2 rings enhanced the interplay of light and color, which was now more important than engraved figural imagery. Even for these cheaper products, a choice of two colors was available. It is not unreasonable to suppose that the different colored gems, or combinations of colors, conveyed specific messages or meanings.

In the case of the octagonal rings, of which a large number date to the 4th c. CE, the attraction was the shape. Swift has noted that polygonal rings never appear in children's sizes and suggests that many were wedding bands.Footnote 48 A number of octagonal gold rings inscribed FIDEM CONSTANTINO were probably owned by members of the army or civil service of the 4th c.Footnote 49 The wearers of the octagonal rings from Wareswald were unlikely to have worked in the imperial administration, though they might have served in auxiliary units of the Roman army. They may simply have wished to imitate an official look, and it is interesting that the only (nearly) male-sized ring in the group is octagonal.

The fact that the Wareswald group, the Rennes Hoard, and the Snettisham Hoard all include a similar number of types, and the Rennes and Wareswald rings share similar visual characteristics, raises an interesting point about ring use. Could it be that there were periodic and regional trends for specific sets of rings? If so, were these rings worn all at once, or were specific types and combinations needed for particular occasions and thus essential in every woman's jewelry box? These questions merit further study, but if such ring sets did exist, then the makers of trinkets could clearly provide them.

Trinket rings and identity

Beyond the functions and specific meanings discussed above, rings might also express social status and identity. They did so well enough that legal and social conventions existed to limit certain ring types to particular groups. Thus, iron rings were sometimes worn by slaves, while in the early Republic they had been worn by senators as a mark of austerity.Footnote 50 In the later Republican and early Imperial periods, gold rings were the exclusive right of senators, magistrates, and equites, while under Septimius Severus, there was a relaxation of the rules, at least within the military.Footnote 51 The rules were different for men and women, and we know, for example, that it was acceptable for Republican women to wear gold rings.Footnote 52 The use of too many rings could be considered effeminate or decadent, while actors, orators, and performers could use rings to achieve specific effects.Footnote 53 Though the surviving textual evidence is too fragmentary to reconstruct the shifting rules of ring-wearing, they were clearly a dress ornament that got noticed and made statements about the identities of their wearers.

Not a single text, however, lays out rules and norms for bronze rings. Nor, for that matter, do we have any evidence that similar social rules were adhered to in Rome's provinces outside of the army. The large number of bronze rings found on Roman sites, however, shows that their use by the provincial population was widespread.Footnote 54 What did their wearers wish to say about themselves?

Most studies of Roman provincial material culture tend to look first for expressions of “native” or “Roman” identity. Since finger-rings did not exist in either the pre-Roman Celtic or the Germanic world but were a strictly Roman dress accessory, their use could be seen as representative of an individual's acceptance of Roman customs.

Yarrow has noted a correlation between the imagery of early glass gems and Republican coins and suggested that these cheaper gems may have been used to express patriotism and Romanitas by non-elite Romans and provincials.Footnote 55 Similarly, on some 1st-c. CE tombstones from Mainz and elsewhere in Germania Superior, rings are depicted prominently on the fingers of deceased men, even in instances where the name of the deceased indicates a Germanic or Celtic background. Thus the ring made a positive statement about the individual's ability to fit into the new social order. Significantly, that statement was being made when provincial society was still forming and contrasts between German, Celt, and Roman were still pronounced.Footnote 56 It is reasonable to assume that the individuals depicted in these reliefs would have used actual rings in the same way.

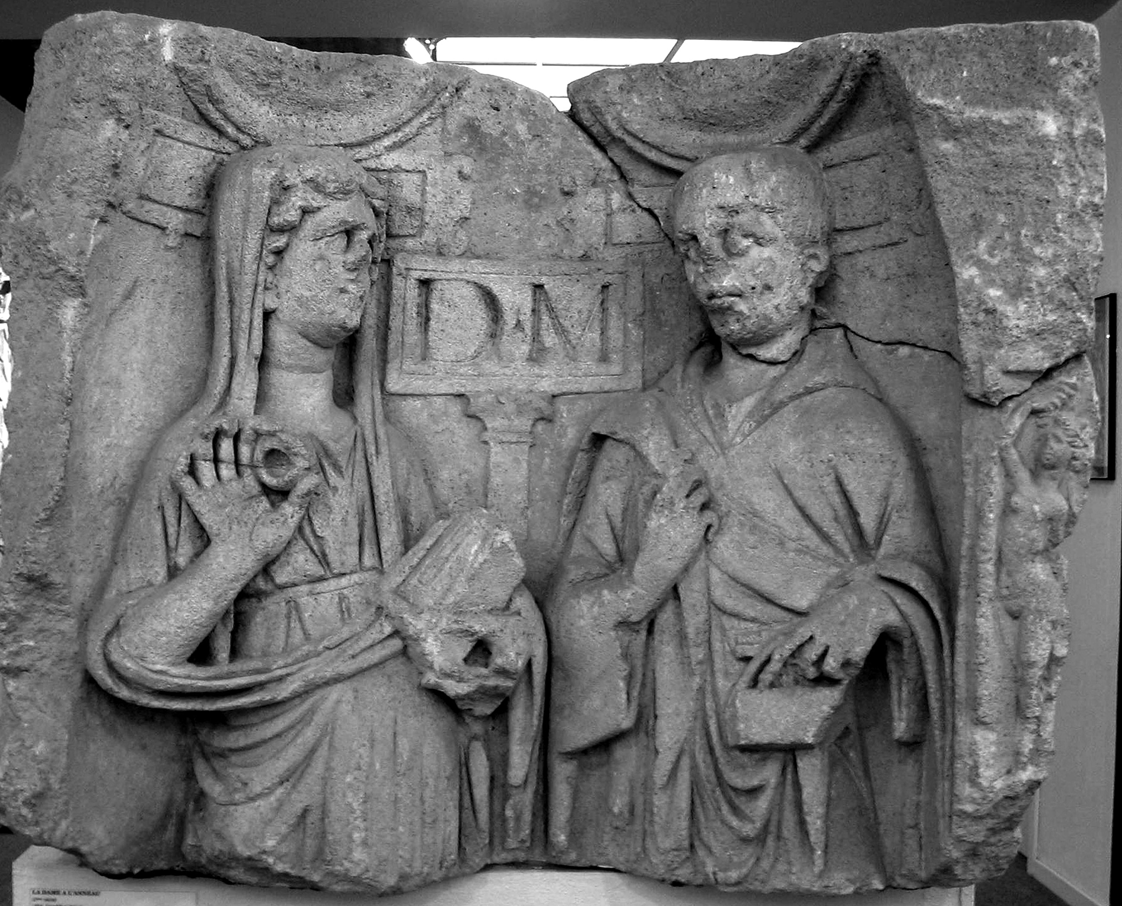

Rings are rare on depictions of males in the funerary monuments of the Treveri.Footnote 57 Representations of women in the funerary art of Gallia Belgica, however, frequently use them as a method of emphasizing the deceased's wealth and sophistication. For example, a funerary relief from Arlon (Fig. 11) depicts a couple side by side, with the veiled wife pulling a ring out of her jewelry box.Footnote 58 Her bearded husband looks on, clutching a stack of writing tablets, his swollen business accounts, in his left hand. Above a long-sleeved tunic, he wears the hooded Gallic cape, or cucullus, a distinctive garment with native origins. The relief emphasizes the business sense and success of the husband, whose wealth has made the rich dress of his wife possible. The ring is just one of several props in a statement about the pair's social status.

Fig. 11. Relief from a funerary monument in Arlon, 150–200 CE, sandstone, 82 cm high. (Photo by P. Kiernan, Musée Archéologique, Arlon).

The Arlon relief dates to a period when provincial society was fully formed and statements about an individual's acceptance of a Roman way of life were probably superfluous. By this point, individuals may have focused on expressing resistance to the globalized Roman world, or, more likely, on the local and regional identities that made them stand out in it.Footnote 59 Thus, the husband in the Arlon relief wears a Gallic cloak. His success is recognizable by a global Roman standard, to which his wife's ring and jewelry box allude, but his cloak tells the viewer that he is still a local man who made good.

It is possible that some trinket rings expressed regional identity in this way, and the fact that rings could be produced in small rural vici like Wareswald raises the possibility of very local types in bronze.Footnote 60 In Britain, signet rings are common in some rural areas but almost entirely absent in others, which seems to confirm the existence of local fashion preferences.Footnote 61 The identification of regional and local ring forms might be a goal for a future study. If they exist, it would be worthwhile to look for other identities that they might have expressed within a global Roman system, and not simply in terms of a dichotomy between Roman and native.

Local, native, and Roman identities were not the only affiliations that rings might attest to. Service in the army or government administration, or membership in any club, guild, or cult could create much stronger group identities, to say nothing of gender, sexuality, marriage, and familial ties. Low- and high-value rings might have made statements about these identities too, even if their meanings are not immediately obvious to us.

In Britain, attempts have also been made to characterize the imagery of engraved gems found at particular types of sites.Footnote 62 In British military contexts, gems tend to be dominated by imperial and legionary imagery (Victoria, imperial portraits, eagles, standards, et cetera) and Mars and other heroic representations are more common than on civilian sites. As Greene has noted, however, the image on an engraved gem might convey a different message in a military context than it would in another setting or to different owners. Thus, images of Greek heroes may simply have appealed to soldiers as depictions of warriors and not because of a specific literary reference.Footnote 63

The Wareswald group is too small, and its intaglio gems too worn, to even hint at a predilection for certain images in the vici of rural Gallia Belgica. But gem choice may well have reflected identity on trinket rings in general. Even though the Wareswald glass nicolos were mass produced, and the importance of the intaglios of later gems is questionable, it is noteworthy that multiple images were still available for customers to choose from.

A large-scale study of the distribution of trinket-ring forms might well be a key not only to identifying local and regional types and ring forms, but also to unlocking the statements they made about identity. Like many trinket rings, the Wareswald rings imitated forms recognizable in gold and silver across the Roman Empire. They even had a goldish appearance when new (Fig. 12). These basic observations suggest the rings may have allowed for pretensions to wealth or made associations and connections that reflected the function and meaning of their expensive counterparts.

Fig. 12. A reconstruction of the Wareswald rings. (Illustration by Marinna Carlson.)

Thus, a cheap ring with a glass nicolo might connect the wearer to the literate world of those who signed and sealed documents or imply that the owner had inherited old heirloom jewelry from a time when sealing was still a common practice. The inscribed rings enabled a special kind of gift exchange, while also pointing to literacy. If not indicators of married status, then the octagonal rings could hint at membership in the select group that had worked in the Imperial administration. Plain glass gems and stones, or rings with enamel inlays not only followed current fashion trends but may have carried color-coded identity signals besides.

In reality, the main shared characteristic of the owners of trinket rings was poverty, and a desire to imitate the costume and lifestyle of the wealthy. Their immense popularity suggests that this aspiration was widespread and that these rings were successful in providing a sense of participation in elite fashions and habits at a very reasonable price.

Acknowledgements

Our thanks to the staff of the Landesdenkmalamt of the Saarland: G. Breitner, W. Adler, N. Kasparek, chief conservator, and S. Brygadin. Our thanks go also to T. Martin, curator of the Museum für Vor- und Frühgeschichte in Saarbrücken. The Kennesaw excavation in Wareswald is generously supported by a grant from The Halle Foundation.

Supplementary Materials

The Supplementary Materials contain a full descriptive catalogue with a typological and comparative study and illustrations (Suppl. Figs. 1–10), as well as additional references. To view the Supplementary Materials for this article, please visit https://doi.org/10.1017/S1047759423000211.