Abstract

As working life changes, it places new demands on vocational competence and the use of different digital technologies. It affects vocational teaching, yet digitalization within vocational education constitutes a scarcely researched area. In this study, we explore how vocational teachers relate to teaching in a digitalized society from a socio-material perspective and explore the possibilities as well as the discursive manifestations of contradictions it gives rise to. Data includes semi-structured interviews with ten vocational teachers, representing eight vocational programs in Sweden. Findings show how vocational teachers benefit from digital technology to realize pedagogical strategies and facilitate students’ vocational competence. At the same time, digitalization entails challenges of keeping up with changes in working life and providing students with relevant vocational digital technologies. Contributions include increased knowledge about digitalization in vocational education, and how it entails navigating different contradictions.

Similar content being viewed by others

Avoid common mistakes on your manuscript.

Introduction

Hardly any organization remains unaffected by the digitalization of society. When digital technology is introduced into work practice, it means that vocational practice develops and changes (Castells, 2011; Karanasios & Allen, 2014, Willermark & Islind, 2022). In an increasingly complex world, our quality of life depends on the knowledge and competence of professionals where education, learning, and teachers gain an increasingly prominent position (Ulferts, 2019).

As working life changes, it places new demands on vocational competence and the use of different technologies (Säljö, 2021). Thus, vocational practices are intimately associated with physical materials such as objects, bodies, technologies, and these settings permit some actions and prevent others (Carlsson 2023; Fenwick 2015). New methods, tools, and processes in working life require vocational teachers to develop fundamental vocational competencies and preparedness for this change (Persson, 2020). Within vocational education, students are educated for work such as carpenters, electricians, and assistant nurses, with the degree objective of developing their vocational competence. The concept of vocational competencies is understood in different ways (Billett, 2001) yet is often portrayed as tacit and situated (Gåfvels & Paul, 2019). Vocational competence can be described as a symmetric relationship between knowledge, skills, and attitudes (Baartman & De Bruijn, 2011; Hiim, 2020). The vocational programs are often stressed as close to practice because of their connection to working life, where practical knowledge is emphasized. At the same time, schools and working life constitutes different contexts that are characterized by different norms and social practices (Billett, 2006). Additionally, vocational education is challenged by rapid changes in professional life which can cause contradictions (Belaya, 2018; Dobricki et al., 2020; Enochsson et al., 2019). Engeström & Sannino, (2011) suggest that there are different types of discursive manifestations of contradictions (hereafter labeled contradictions) that determine the degree of the contradiction and how easily (or difficult) they are managed in practice. Being a vocational teacher means relating to working life and teaching practice in constant change, which has been intensified by the digitalization of society. This is also reflected in policy. In Sweden, digitalization in schools is driven by the national strategy for digitalization from the government (The Swedish agency for Education, 2022; Ministry of Education 2017) proclaiming that Sweden should become world-leading in taking advantage of the possibilities of digitalization. In vocational programs, teachers must also consider the vocational curricula regarding digitalization, where the ability to handle tools and materials is frequently mentioned. In this study, we explore vocational teachers’ perspectives on preparing students for future working life. More specifically, we ask the following research question: What contradictions can be identified when teachers relate to teaching in a digitalized society?

Related Research

The mission of the vocational teacher is to prepare their students for working life as well as for citizenship (Kontio & Lundmark, 2021; Rosvall et al., 2020). Rapid and ongoing changes in working life with technological development have put pressure on vocational education and training to become more responsive to the needs of society and working life, and sometimes give rise to contradictions (Belaya, 2018; Dobricki et al., 2020; Enochsson et al., 2019). Still, the digitalization of vocational education constitutes an under-researched field of study, not least in a Swedish context (Asplund & Kontio, 2020; Kontio & Lundmark, 2021). Nevertheless, there is a stream of research that has explored digitalization within vocational education and how different digital technologies such as blogs, video-based instructions, e-portfolios, workplace simulations, and hyper-videos (Belaya, 2018; Hamid et al., 2020; Jossberger et al., 2015) can be used in vocational education. Furthermore, in a recent literature review, Dobricki et al. (2020) examine vocational education. According to the authors, the digital transformation of working life raises questions about how to use digital technologies in vocational teaching in a way that creates authentic connections to working life (Dobricki et al., 2020). The results show that digitalization is often manifested via teachers’ use of digital photos, videos, and the internet for educational scaffolding or learning tasks. In more recent examples, videos of work situations and work situations presented in a 3D virtual environment are used to imitate authentic situations within vocational education (Dobricki et al., 2020). There are a few recent studies that explore the digitalization of vocational education in Sweden. Since vocations are intimately associated with physical and digital material, access to qualitative teaching material is described as crucial for education (Juhlin Svensson, 2000; Kontio & Lundmark, 2021). However, selecting teaching material has shown to be a complex task. It includes aspects of what learning material is available to the teacher, the cost, and the time required to select materials (Kontio & Lundmark, 2021). Enochsson et al., (2020) show how vocational teachers perceive challenges of keeping up with the development of industry, the lack of access to vocational relevant technology in school, and the difficulties in cooperating with internship places. Asplund and Kontio, (2020) examine the challenges and possibilities linked to the digitalization of vocational education by exploring students’ collective use of smartphones in interaction during classes. The findings reveal how the smartphone plays a role in students identity constructing processes that intersect with the students’ future vocational identity as building and constructing workers, yet also explicating an ‘anti-school culture’. It shows how digitization causes a contradiction in vocational education. Overall, previous studies highlight the intimate connection between materials and vocational education and how gaps arise between working life and school, not least linked to digitalization.

Socio Materiality and Contradictions

We use socio-materiality and contradictions to analyze how vocational teachers relate to teaching in a digitalized society, with its inherent digitalization of working life and education. Socio-materiality offers a view of humans and technology as entangled and mutual dependence while contradictions shed light on different types of contradictions that can be found within a practice, in this case, vocational teaching.

Socio-materiality

The concept of socio-materiality offers a view of humans and technology as interdependent and integrated, where the social and the material are seen as inherently inseparable (Orlikowski & Scott, 2008). Thus, relationality and interaction between humans and technology are in focus (Cerratto Pargman, 2023; Orlikowski 2007). Orlikowsky & Scott (2015) emphasizes that practice is changing depending on how a material is used in practice. Material like digital technology, artifacts, bodies, and environments facilitate as well as prevent different actions (Orlikowski, 2007). Seeing learning as intimately connected to socio-material resources opens the idea of learning as something performative and the understanding of using resources in productive ways (Gunarsson, 2018; Jain, 2022; Säljö 2015). Performativity is one of the key characteristics in socio-material theory and can be defined as “the enactment of relations and boundaries between people and technology. It emphasizes that realities are not given but performed in ongoing practices” (Jain, 2022, pp. 2). Within all practices, there is always a need for mastering the materiality of the practice (Nyström, 2020, Säljö, 2021). Materiality and interaction with the material are foundational for the learning and development of individuals and collectives (Säljö, 2021). Vocational teachers are mastering the socio-materiality of the teaching practice as well as the vocational practice in which their students aim to develop vocational competence (Nyström, 2020). Vocational teachers relate to a variety of materials in their teaching. They can be either primarily pedagogical in nature or primarily profession-specific, analog, or digital. Säljö (2021) points out that without our external material our capability is limited, but with access to texts, databases, and other material it is practically unlimited. In this study, the concept of socio-materiality contributes to an increased understanding of how teachers discuss how teaching material is integrated with social activities in the teaching practice.

Contradictions

The vocational teachers express that they have experienced how working life is changing which causes them to navigate different contradictions. Engeström and Sannino (2011) suggest that there are four types of discursive manifestations of contradictions, namely dilemmas, conflicts, critical conflicts, and double binds. These manifestations of contradictions are different in how they affect learning and in how easily they are managed. Contradictions are historically emergent, systemic phenomena that can be approached through their manifestations which become recognized when practitioners articulate and construct them in words and actions (Engeström & Sannino, 2011). Dilemmas can roughly be explained as an expression or exchange of incompatible evaluations. The incompatibility is either between people or within the person. It is often expressed in the shape of hedges and hesitations such as “on the one hand”, on the other hand, or “yes, but”. Dilemmas are usually not resolved but rather denied or reformulated. Conflicts take the form of resistance, disagreement, argument, and criticism, and expressions of conflicts are typical; “no”, “I disagree”, and “This is not true”. Critical conflicts are typical situations in which people face inner doubts that paralyze them. In social interaction, critical conflicts involve feelings of being violated or guilty and subjects often feel silenced. Handling critical conflicts involves personal, emotional, and morally charged processes. The resolution of critical conflicts takes the form of finding new personal sense and negotiating a new meaning for the situation. Double binds are processes in which subjects repeatedly face pressing and equally unacceptable alternatives in their activity system where there seems to be no way out. There seem to be expressions about the pressing need to do something together with a perceived impossibility of action. Desperate rhetorical questions are typical, i.e., what can we do? What is special about a double bind is also that no person alone can resolve it. A transition from the individual focus to a collective emerged as a resolution and transformative agency in practical and collective action. ‘Double bind’ becomes an important concept in how we can understand the actions in the group in relation to contradictions. The experience can be described as “something needs to be done” but there is no obvious way how to proceed (Engeström & Sannino, 2011).

Method

Qualitative interviews were conducted with 10 vocational teachers from 8 different vocational programs in Swedish upper secondary vocational education (see Table 1 for an overview of the respondents). The participants were recruited from a previous survey carried out by the authors (Carlsson, 2022) that explored vocational teachers’ experiences in using and developing teaching material. In the survey, there was a possibility of accepting an invitation to participate in an interview and eight teachers volunteered to participate. To increase the variation of the vocational programs represented, two additional vocational teachers (outside the survey) were invited to participate. Thus, the sample can be described as strategic (Bryman, 2016). All the participants were vocational teachers teaching in vocational programs at the upper secondary education level.

A pilot interview was conducted to determine the suitability of the semi-structured interview guide which mainly led to the rearranging of the order of the questions and the removal of one question (Elo et al., 2014). The interview guide included general questions about how the respondents viewed their teaching assignments in general, opportunities and challenges in their role as vocational teachers, and learning resources. Furthermore, specific questions about how they perceive that the digitalization of society and school, is affecting their teaching were addressed. The interviews lasted between 35 and 60 min (average time 44 min) and were transcribed verbatim. The interviews took place within the respondents’ workplaces. In four cases, the interview was supplemented with classroom visits, where the informant also showed their teaching environment. However, this was not possible in all cases due to the time available for the informant.

Data Analysis

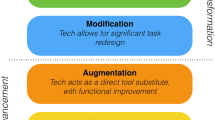

A qualitative content analysis was carried out (Graneheim et al., 2017), where the data was processed in different steps (see Fig. 1 for an overview). First, the authors read the transcripts in full, to get an overall understanding of the material. In line with the purpose of the study, the authors selected the parts in the transcriptions that in some way addressed digitalization in vocational education. Then, the first author divided the text into meaning units and condensed the units. Codes were created, such as “Learning resources online”, “Digital learning resources connected to vocation” or “smart phone as central in teaching for the vocation”. Thereafter, both authors reviewed and clustered the codes with similar content into two main themes. The two themes “Vocation in Flux” and “Teaching in Flux” reflected how teachers perceive that digitalization of society affects both vocations and teaching practices. In the last step, discursive manifestations were applied to categorize and analyze the data.

Ethics

Informed Consent

was gathered from all informants. During the interview, informants were provided with both verbal and written information about the aim of the study, that they could withdraw their participation at any stage of the interview without giving reasons, and that their personal information would be dealt with to respect to their integrity. An ethical approval application was made to the Swedish Board for Ethical Approval (dnr: 2021–04827) yet the application was judged not to need ethical approval.

Results and Analysis

First, vocational teachers’ perspectives of how the digitalization of society affects the vocations they are teaching are presented followed by how it affects their teaching practice.

Vocations in Flux

Vocational teachers describe that the digitalization of society affects the vocations that they teach. Yet, while some emphasize how the vocation is fundamentally shaken to its core, others stress that much is constant and that the foundation of the vocation remains stable. Thus, how the digitalization of society is affecting vocations and consequently the teaching varies greatly among teachers. Konstantin at the Vehicle and Transport program portrays an industry facing extensive transformation as electric cars are becoming the ‘new normal’. It is changing the role of a mechanic, who must learn how a new generation of cars works, as illustrated by: “the thing is that electric cars […] there are all based on you plugging in a computer […] so this means that the industry is changing and that private individuals should no longer be able to tinker with the cars at home as they do with a vintage car… Then you notice how the digital world has really taken over”. He described a vocation that goes from being associated with tinkering with the vehicle with greasy hands and hand-held tools to digital troubleshooting and plastic visors to protect against electric shocks. Konstantin argues that the objectives of the program do not keep pace with societal development and the restructuring of the industry and finds it highly problematic. This situation can be understood as a double bind (Engeström & Sannino, 2011) as he describes a system-level contradiction between vocational and teaching practice, that he and his colleagues alone cannot resolve. Similarly, Rebecka, within the healthcare program describes how a rapid development of knowledge, innovations, and technologies poses a challenge in terms of preparing students for future vocations, as illustrated by; “It [the medical innovation] is moving forward extremely quickly compared to our education. So even if we were to buy, for example, a bladder scan [an ultrasound to see how much urine the patient has in the bladder] that students will use as soon as they arrive at a hospital… still, two years later, it doesn’t look like that anymore… it moves forward so fast…”. Rebecka describes how this creates a challenging situation in terms of preparing students for their future vocations, and that ‘something needs to be done’, still, there is no obvious way how to proceed, understood as double bind (Engeström & Sannino, 2011). Also, Cornelia within the Restaurant and Food program described a discrepancy between the technologies provided at school and those applied in changing working life. It mainly applies to administrative systems for, for example, calculating nutritional value or placing orders. However, from her perspective, it does not imply any fundamental gaps between education and practice. Instead, incompatibility is reformulated as something that can be handled through creative methods, which characterizes a dilemma (Engeström & Sannino, 2011). Cornelia describes how she addresses these issues for example by utilizing study visits, as illustrated by; […] “there are computer programs etcetera and we can’t have all those programs here… but, I get around that by visiting the industry, taking them [the students] out on study visits…”. Some teachers describe how more general or mundane technology has become part of vocations everyday life. In these cases, changes in vocation are often described as less disruptive and more in terms of a change in the implementation of work tasks.

Teaching in Flux

Teachers describe how they digitalize their teaching and make use of opportunities with digitalization, but also how digitalization gives rise to contradictions within teaching practice. Teachers describe how digitalization is affecting teaching in numerous ways. They use a variety of digital technology to facilitate their students’ learning. It includes supporting general pedagogical approaches such as enabling interactivity, and variation in teaching as well as adapting their teaching to the individual students’ needs. Teachers describe the use of learning management systems for administration, communication, and teaching in combination with other digital technologies designed for teaching purposes such as digital learning material, and digital assistive tools. Furthermore, teachers describe how they use a wide range of digital technologies such as social media, quizzes, videos, and pictures as well as create their own teaching material including presentations, videos, pictures, and texts. Much of the teachers’ use of digital technology can be traced to the aim of meeting the needs of the individual student by the level adjustment of tasks, instructions, and assignments. In addition to the use of digital technologies to support general pedagogical approaches, teachers describe the use of vocational digital technologies. It includes situations where digital technology is used to learn content-specific competencies for working life, where digital technology becomes a central part of the learning content. Digital technologies are frequently used to invite working life scenarios into classroom practice and are described as the second best, after reality. It can involve recording an instructional video on how to conduct cargo securing within the Vehicle and Transport program or creating libraries with useful links to recipes to direct the students to valid content within the Restaurant and Food program. There are also examples of applying vocation-specific digital technologies. Lennart is using 3D programs when teaching his students programming in the automation courses, a task the students are likely to continue doing if they work in automation. Andreas describes how they use digital instruments to measure electricity when digging down cables in the ground close to the school building or ordering materials from wholesalers in class. There are several examples of how vocational teachers stress the importance of materiality and its impact on learning. For example, vocational teachers describe how they turn to work life and try to adapt their digital technologies in their teaching yet meet obstacles in doing so. Peter has planned to use a program for the customer- orders that electricians use (most of the time from their smartphones) in some of the local firms to mimic working life routines. However, using that system requires a network that allows different devices to connect to Wi-Fi which the locked network at school does not allow, which leads us to contradictions. Some vocational teachers describe the lack of vocational-specific digital technologies as problematic for reaching curricular goals, thus developing vocational competencies. As pointed out by Säljö, (2021), without external material our capability is limited, but with access to adequate material our capability is practically unlimited.

As pointed out by Engeström and Sannino (2011) dilemmas can be understood as an expression or exchange of incompatible evaluations between people or within the person. Dilemmas can be identified among vocational teachers, triggered by a lack of access to adequate digital technologies in working life. For instance, Rebecka describes how working in health care often includes documentation and reporting in journal systems, which becomes difficult to teach, as illustrated by; “We are missing that [documentation and reporting systems] today, we can only talk about it”. During an internship, students can sit next to a person documenting but there is no room for practice. The situation causes a dilemma because of the incompatible demands connected to expectations from working life, expectations in the curricula and the prerequisites in teaching. Rebecka already intends to work with language development in her teaching but wants to practice how documentation in patient journals is made. She is obliged to do both. She has access to a method room where students are practicing their role as assistant nurses by roleplaying, but she expresses how this could be enhanced using a digital documentation system, not least when it comes to developing vocational language. In similar ways, Cornelia speaks about learning vocation-specific digital technology in work within restaurants as illustrated by; “we have a checkout system but that is not the only system, hopefully, they see others in their internship”. Both describe this as a process where the teaching material in school is not updated and has no chance of being so. This is mentioned as a dilemma that is not possible or needed to resolve. Another dilemma is linked to the smartphone in teaching. Within vocational teaching, the smartphone has in some sense become increasingly analogous to a “Swiss Army knife” as providing a plethora of readily accessible technologies for (working) life. It is used both for mundane activities as well as teaching to develop profession-specific knowledge. It includes activities such as ordering from the wholesaler, calculation, controlling devices with applications, planning work, etc. Teachers at all vocational programs provide several reasons for using smartphones in the vocation they are aiming at and claim that they are useful in their teaching because of their vocational relevance. Thus, from one perspective, the smartphone is considered an important technology that supports pedagogical approaches and knowledge relevant to vocation, from the other perspective it considers causing disruption in teaching. Victor describes how the calendar on the phone is crucial for planning work tasks as well as creating invoice documents within the vocation. At the same time, he expresses that; “they [the students] need to understand that the smartphone is more than entertainment”. He expresses frustration that students do not learn how to use the smartphone in an adequate way for (working)life. An expression characteristically of a dilemma (Engeström & Sannino, 2011) with criticism and resistance towards societal development but at the same time understanding of the importance to relate to the technology relevant to working life. Similarly, Rebecka says that: “there is no better way to observe a wound heal (or not) than to take pictures of it [using a smartphone], you can never describe that as good with words or with a text”. In the next sentence, she expresses hesitation and explains how smartphones are a disadvantage to students struggling with concentration and learning, something which can be seen as an expression of internal dilemma. However, the smartphone also causes conflict, understood as manifestations of resistance, disagreement, argument, and criticism (Engeström & Sannino, 2011). The smartphone constitutes a controversial technology that causes conflict when teachers describe how their idea of how to integrate the smartphone into teaching clashes with the organizational policy of banning smartphones in class, as illustrated by; “We have been ordered to take the phones away when they come to class and I’m really against it because I want them to learn how to handle the phone as a tool” (Lennart). Thus, for teachers like Viktor, Peter, and Lennart the smartphone constitutes a natural technology in teaching and an important vocational tool, that conflicts with local regulations. Another conflict that many teachers express is related to the fact that there are a lot of different courses where they lack adequate knowledge of what constitutes relevant professional knowledge and professional material. This could be interpreted as a critical conflict at times when the situation is paralyzing or gives rise to feelings of guilt for the individual (Engeström & Sannino, 2011). Vocational teachers describe how they sometimes teach courses where they lack their own working experience and many stress that they feel expectations of being updated in vocation-specific digital development, which is impossible to squeeze into their working hours. For example, Olof expresses feelings of guilt when not focusing on digital development at the Child and Recreation program; “We see how tablets are used in many of our occupations as assistive tools so it is a wonderful tool for many of our users… and it is used in preschools and primary schools, so, of course, we need knowledge about that//but we haven’t had the time, you struggle with other things all the time.” In summary, we see how contradictions manifested as dilemmas, conflicts, critical conflicts, and double binds emerge from vocational teachers’ encounters with a changed socio-materiality driven by digitalization in society.

Discussions

Socio-materiality is changing the procedure of how work is conducted, which impacts on how teaching and learning are to be. Thus, it is clear how intimately connected and intertwined digitalization is with pedagogy and vocational content. Sometimes digital technology is seen as a purely pedagogical resource but moreoften it is part of the content to be taught. Thus, in vocational teaching, the objective is often directed toward learning how to handle digital technologies within a profession (Orlikowski, 2007; Säljö, 2021). The findings indicate that the digitalized working life causes different contradictions in teaching practices, which is in line with previous research (Belaya, 2018; Dobricki et al., 2020). The contradictions that teachers have to navigate can be synthesized into three overarching types addressed below.

Navigating the Contradictions Between Vocation and Teaching in Flux

Vocational teachers describe that the digitalization of society affects vocation. Yet, while some emphasize how the vocation is fundamentally shaken to its core, others stress much more moderate adjustment. From some, the development in vocation is described as almost revolutionary and as double binds, with a large discrepancy between education and vocational practice. Others describe a more evolutionary development where the contradictions are not particularly great but can be managed within the prevailing practice. Thus, vocational education is not homogeneous. After all, there are 12 vocational programs including over 200 subjects. The availability of adequate digital technologies also creates contradictions, where the technologies of the industry are not provided in the school, while teachers describe creative ways to address it in their teaching. In practice, it is the teachers, the principles, and the market that is influential in deciding which technology the students will meet during their vocational education (Lilja Waltå, 2016). Thus, teachers describe how industry connections became crucial to accessing material when school funding is insufficient and gives rise to creative solutions.

Navigating the Contradictions Between Different Curricula

Repeatedly, teachers describe dilemmas regarding how they teach by the goals expressed in the curriculum and the student’s varying needs but also the expectations from working life. Billett (2006) suggests that there is a workplace curriculum as well as an educational curriculum. The workplace curriculum can be described as the way individuals learn how to work functionally and develop in connection to the specific workplace. The workplace and the educational context are two different practices with their own curricula. Carlgren (2017) explains this situation as the practices have two different main focuses, whereas in school learning is in the foreground and at the workplace, learning is a byproduct. Navigating this situation, in this educational context, this contradiction causes frustration but also cultivates creative approaches that involve vocational digital technologies. Performativity is a way to discuss socio-material aspects of creativity in vocational teaching practice. Vocational teachers are creating their own teaching material to navigate that dilemma. They are also trying to find ways to integrate vocational-specific digital technology to reach curricular goals and at the same time create authentic and relevant teaching situations applicable to a digitalized working life.

Navigating the Contradictions of Supportive and Disruptive Digital Technologies

We see that digital technology is both central and generally used, however, not uncontroversial. It is understood as both a possibility and as a disruption in vocational teaching practice. Sometimes tablets, computers and smartphones are seen as relevant general pedagogic tools for creating podcasts, searching for information, or communicating on the learning platform, as well as performing vocational tasks. At the same time, digital technology and especially the smartphone is also seen as a somewhat controversial issue in the data causing both conflict and dilemma. It was both considered a powerful vocational technology and a disruption at work and in teaching. It is in line with previous research that shows how the smartphone constitutes a controversial technology in school in general and that it can both facilitate schoolwork as well as function as a distraction (Ott et al., 2018; Thomas & Muñoz, 2016). It is also in line with Nordby et al. (2017) who show how the smartphone can be used for creating authentic teaching situations. Moreover, Langseth and Sedal (2019) argue that involving the students in ways that will empower them to control their activity when using the smartphone is a way to deal with this dilemma, which also was displayed in the data. From a socio-material perspective, we see expressions of the understanding of the social and the material as inseparable and constituting in this study. Digital technology affects teaching in contradictory ways but also becomes what teachers make them become.

Limitations and Future Directions

This study has limitations that should be addressed. The study is bound to the context of Sweden with its curricula, educational objectives, and other frameworks that govern the school. Furthermore, only 8 out of a total of 12 vocational programs are represented in the data despite attempts to recruit respondents from all programs. This means that the data does not capture representatives from all vocational programs. Furthermore, the empirical data is relatively limited. At the same time, in qualitative studies, the crucial issue is not whether the results are generalizable to a larger population, but how well they succeed in generating theory, also referred to as “analytical generalization” (Yin, 2009). Thus, it is the explanatory power of theoretical reasoning that becomes relevant when assessing the results. Our stance is that the results from this study have broader theoretical implications than explain this specific study, as it illustrates different narratives of how vocational teachers perceive, and relate to, teaching with digital technology, in the light of the digitalization of society. A future area of research will be to explore how the digitalization of vocational education is manifested in practice by observations on teaching activities to capture reflections on the socio materiality of vocational teaching.

Conclusion

In this study, we have explored how vocational teachers relate to teaching in a digitalized society from a socio-material perspective, using the lens of discursive manifestations. We have shown how teachers relate to and make use of digital technology in their teaching while also giving rise to difficulties of various kinds. Contributions include increased knowledge about digitalization in vocational education, and how it entails navigating contradictions between (i) vocations and teaching in flux, (ii) between different curricula, and (iii) supportive and disruptive digital technologies.

References

Asplund, S. B., & Kontio, J. (2020). Becoming a construction worker in the connected classroom: Opposing school work with smartphones as happy objects. Nordic Journal of Vocational Education and Training, 10(1), 65–94. https://doi.org/10.3384/njvet.2242-458X.2010165

Baartman, L. K., & De Bruijn, E. (2011). Integrating knowledge, skills and attitudes: Conceptualising learning processes towards vocational competence. Educational Research Review, 6(2), 125–134. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.edurev.2011.03.001

Belaya, V. (2018). The Use of e-Learning in Vocational Education and Training (VET): Systematization of existing theoretical approaches. Journal of education and learning, 7(5), 92–101. https://doi.org/10.5539/jel.v7n5p92

Billett, S. (2001). Knowing in practice: Re-conceptualising vocational expertise. Learning and instruction, 11(6), 431–452. https://doi.org/10.1016/S0959-4752(00)00040-2

Billett, S. (2006). Constituting the workplace curriculum. Journal of Curriculum Studies, 38(1), 31–48. https://doi.org/10.1080/00220270500153781

Bryman, A. (2016). Social research methods. Oxford university press.

Carlgren, I. (2017). Yrkesdidaktiska vägval. I: Fejes, A, Lindberg, V. & Wärvik (red), Yrkesdidaktikens mångfald, (s. 255–268). Stockholm, Lärarförlaget.

Carlsson, S., K Flensner, K., Svensson, L., & Willermark, S. (2023). Teaching vocational pupils in their pyjamas: a socio-material perspective on challenges in the age of Covid-19. The international journal of information and learning technology, 40(1), 84–97. https://doi.org/10.1108/IJILT-03-2022-0064

Carlsson, S., & Willermark, S. (2022). Designing teaching material for workplace pedagogy in school. In ICERI2022 Proceedings (pp. 1154–1159). IATED. https://doi.org/10.21125/iceri.2022.0312

Castells, M. (2011). The rise of the network society: The information age: Economy, society, and culture (1 vol.). John Wiley & Sons.

Cerratto Pargman, T. (2023). Reconsidering learning in a socio-material world. A response to Fischer et al.‘s contribution. The international journal of information and learning technology, 40(1), 40–48. https://doi.org/10.1108/IJILT-07-2022-0143

Dobricki, M., Evi-Colombo, A., & Cattaneo, A. (2020). Situating vocational learning and teaching using digital technologies-a mapping review of current research literature. International journal for research in vocational education and training, 7(3), 344–360. https://doi.org/10.13152/IJRVET.7.3.5

Elo, S., Kääriäinen, M., Kanste, O., Pölkki, T., Utriainen, K., & Kyngäs, H. (2014). Qualitative content analysis: A focus on trustworthiness. SAGE open, 4(1), 2158244014522633. https://doi.org/10.1177/2158244014522

Engeström, Y., & Sannino, A. (2011). Discursive manifestations of contradictions in organizational change efforts: A methodological framework. Journal of organizational change management. https://doi.org/10.1108/09534811111132758

Enochsson, A. B., Andersén, A., Kilbrink, N., & Ådefors, A. (2019). Vocational Teachers’ Use of Digital Technology as Boundary Objects–Obstacles for Progress. ECER 2019

Enochsson, A. B., Kilbrink, N., Andersén, A., & Ådefors, A. (2020). Connecting school and workplace with digital technology: Teachers’ experiences of gaps that can be bridged. Nordic Journal of Vocational Education and Training, 10(1), 43–64. https://doi.org/10.3384/njvet.2242-458X.2010143

Fenwick, T. (2015). Sociomateriality and learning: A critical approach.The Sage handbook of learning,83–93.

Gåfvels, C., & Paul, E. (2019). LÄRLING ELLER SKOLUTBILDNING: Olika vägar mot samma mål? [APPRENTICE OR SCHOOL EDUCATION: Different paths aiming for the same goal?]. In: Skolverket.

Graneheim, U. H., Lindgren, B. M., & Lundman, B. (2017). Methodological challenges in qualitative content analysis: A discussion paper. Nurse Education Today, 56, 29–34. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.nedt.2017.06.002

Gunnarsson, K. (2018). Med rörelse och engagemang: En sociomateriell hållning till praktiknära skolforskning. [With movement and commitment: A socio material attitude towards school research close to practice]. Utbildning och Lärande/Education and Learning, 12(1), 71–86.

Hamid, M. A., Yuliawati, L., & Aribowo, D. (2020). Feasibility of Electromechanical Basic Work E-Module as a New Learning Media for Vocational Students. Journal of Education and Learning (EduLearn), 14(2), 199–211. https://doi.org/10.11591/edulearn.v14i2.15923

Hiim, H. (2020). Å vurdere yrkeskompetanse: Hva er yrkeskompetanse, og hvordan kan den vurderes?[Evaluating vocational competence: What is vocational competence, and how can it be evaluated?]. Nordic Journal of Vocational Education and Training, 10(3), 45–66. https://doi.org/10.3384/njvet.2242-458X.2010345

Jain, A., & Srinivasan, V. (2022). What happened to the work I was doing? Sociomateriality and cognitive tensions in technology work. Organizational Dynamics, 51(4), 100901. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.orgdyn.2022.100901

Jossberger, H., Brand-Gruwel, S., van de Wiel, M. W., & Boshuizen, H. P. (2015). Teachers’ perceptions of teaching in Workplace Simulations in Vocational Education. Vocations and learning, 8(3), 287–318. https://doi.org/10.1007/s12186-015-9137-0

Juhlin Svensson, A. C. (2000). Nya redskap för lärande: Studier av lärarens val och användning av läromedel i gymnasieskolan. [New tools for learning: Studies of teachers choices and use of learning material in school]. HLS förlag].

Karanasios, S., & Allen, D. (2014). Mobile technology in mobile work: Contradictions and congruencies in activity systems. European Journal of information systems, 23(5), 529–542. https://doi.org/10.1057/ejis.2014.20

Kontio, J., & Lundmark, S. (2021). Yrkesdidaktiska dilemman. [Vocational didactical dilemmas]. Natur & Kultur.

Langseth, I. D., & Sedal, H. (2019). Smart phones in schools: In what Ways can Coaching empower students to make a valid judgement on when and how to use their smart phone? Human IT: Journal for Information Technology Studies as a Human Science, 14(3), 48–82.

Lilja Waltå, K. (2016). " Äger du en skruvmejsel?” Litteraturstudiets roll i läromedel för gymnasiets yrkesinriktade program under Lpf 94 och Gy 2011. [Do you own a screwdriver? The role of literature studies in learningmaterial for vocational programs under Lpf94 and Gy2011].

Ministry of Education. (2017). Nationell digitaliseringsstrategi för skolväsendet. [National strategy for digitalization of the schoolsystem].

Nordby, M., Knain, E., & Jonsdottir, G. (2017). Vocational students’ meaning-making in school science-negotiating authenticity through multimodal mobile learning. NorDiNa: Nordic Studies in Science Education, 13(1), 52–65. https://doi.org/10.5617/nordina.2976

Nyström, S., & Ahn, S. E. (2020). Simulation-based training in VET through the lens of a sociomaterial perspective. Nordic Journal of Vocational Education and Training, 10(1), 1–17. https://doi.org/10.3384/njvet.2242-458X.201011

Orlikowski, W. J. (2007). Sociomaterial practices: Exploring technology at work. Organization studies, 28(9), 1435–1448. https://doi.org/10.1177/0170840607081138

Orlikowski, W. J., & Scott, S. V. (2008). 10 sociomateriality: Challenging the separation of technology, work and organization. Academy of Management annals, 2(1), 433–474. https://doi.org/10.5465/19416520802211644

Orlikowski, W. J., & Scott, S. V. (2015). The Algorithm and the Crowd: Considering the Materiality of Service Innovation. MIS Quarterly, 39(1), 201–216.

Ott, T., Magnusson, A. G., Weilenmann, A., & Hård, Y. (2018). “It must not disturb, it’s as simple as that”: Students’ voices on mobile phones in the infrastructure for learning in Swedish upper secondary school. Education and Information Technologies, 23(1), 517–536. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10639-017-9615-0

Persson, M. (2020). Digitalisering i yrkesutbildningen inom samhällsbyggnadssektorn: En förstudie. [Digitalisation in vocational education within the built environment sector: A pre studie]. In: Malmö universitet.

Rosvall, P., Ledman, K., Nylund, M., & Rönnlund, M. (2020). Yrkesämnena och skolans demokratiuppdrag. [Vocational subjects and the democracy mission in school]. Gleerups. https://gup.ub.gu.se/publication/297897

Säljö, R. (2021). Från materialitet till sociomaterialitet: Lärande i en designad värld. [From materiality to to sociomateriality: Learning in a designed world]. Techne serien-Forskning i slöjdpedagogik och slöjdvetenskap, 28(4), 193–208. https://doi.org/10.7577/TechneA.4736

Säljö, R. (2015). Lärande-en introduktion till perspektiv och metaforer. Malmö: Gleerups. https://gup.ub.gu.se/publication/206309

The Swedish National Agency for Education (2022). Förslag till nationell digitaliseringsstrategi för skolväsendet 2023–2027. [Suggestion for national strategy for digitalization of the school system]. (2022:1293) Stockholm. https://www.skolverket.se/publikationer?id=10849

Thomas, K., & Muñoz, M. A. (2016). Hold the phone! High school students perceptions of mobilephone integration in the classroom.American Secondary Education,19–37. https://www.jstor.org/stable/45147885

Ulferts, H. (2019). The relevance of general pedagogical knowledge for successful teaching: Systematic review and meta-analysis of the international evidence from primary to tertiary education. https://doi.org/10.1787/ede8feb6-en

Willermark, S., & Islind, A. S. (2022). Adopting to the virtual workplace: identifying leadership affordances in virtual schools. Journal of Workplace Learning, (ahead-of-print). https://doi.org/10.1108/JWL-05-2022-0052

Yin, R. K. (2009). Case study research: Design and methods (5 vol.). Sage.

Acknowledgements

This work was supported by the Swedish Research Council [No. 2019–03607]. Furthermore, we would like to express our appreciation to the teachers that contributed to this study.

Funding

Open access funding provided by University West.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Competing of Interest

The authors have no competing interests to declare that are relevant to the content of this article.

Additional information

Publisher’s Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License, which permits use, sharing, adaptation, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if changes were made. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article’s Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article’s Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Carlsson, S., Willermark, S. Teaching Here and Now but for the Future: Vocational Teachers’ Perspective on Teaching in Flux. Vocations and Learning 16, 443–457 (2023). https://doi.org/10.1007/s12186-023-09324-z

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s12186-023-09324-z