Abstract

This study extends and tests a model determining how customer perceived benefits affect perceived relationship investment and brand relationship quality as mediators to behavioural and attitudinal loyalty with type and timing of rewards as moderators. A quantitative methodology and survey approach was applied using randomly selected stratified sampling resulting in 277 financial services loyalty programme member respondents. The hypotheses were tested using structural equation modelling. The results highlight social and exploration benefits to be much stronger determinants of customer loyalty than monetary and entertainment benefits, with recognition having no effect and timing of rewards moderating the influence of monetary and exploratory benefits. The type of reward moderated the influence of entertainment and exploratory rewards. The study’s theoretical contribution provides for an empirically validated comprehensive conceptual model of loyalty programme effectiveness for the financial services industry and very important loyalty programme design findings for practitioners.

Similar content being viewed by others

Avoid common mistakes on your manuscript.

Introduction

The financial services industry has experienced a number of crises, of which the 2007/8 economic crisis led to severe losses by banks (Acharya 2013), and an erosion of customer trust. Although the COVID-19 pandemic has not impacted bank profitability as seriously as expected (McKinsey & Company 2021; Deloitte 2022), most banks are operating at return-on-equity levels that are lower than return-on-cost ratios, with profitability improvements expected in line with the post-recession global economic recovery (Deloitte 2022). An increase in scale and revenue through innovative ecosystems driving customer value has been recommended to overcome the highly divergent and varied post-recession growth recovery of financial institutions (McKinsey & Company 2021).

To add to the pressure on profitability and growth of financial institutions, traditional financial service offerings are being challenged as payment networks are opened by non-financial institutions such as KakaoPay (payment enablement of Kakao Talk, a mobile instant messaging service in South Korea), Apple Pay (iPhone feature) and Alipay (Ant Financial, an affiliate of Alibaba), evolving into digital banks providing consumer lending, insurance, wealth management and more. Data rules are also being relaxed, enabling Fintech digital start-ups such as Monzo, Mint, Curve and Receipt Bank to offer new and innovative financial services related to account aggregation and improved financial management on a single platform (integrating customer financial products across institutions) (Rainmakrr 2021). Twenty new banks have recently been launched in the UK (the world’s largest exporter of financial services), posing a real threat to traditional financial institutions globally (Du Toit and Cuthell 2019).

In order to combat both increased competition and profitability pressures, financial institutions are prioritising customer loyalty and relationship management as key marketing strategies driving customer value (Picon-Berjoyo et al 2016; Du Toit and Cuthell 2019). Loyalty programmes form an integral part of these strategies, and the effectiveness of loyalty programme design to drive long-term value is of utmost importance. Financial institutions need to ensure that they retain customer engagement and loyalty by creating relevant customer value through their loyalty programmes. US banks with high customer loyalty measures have outperformed the market average in the past three years (Du Toit and Cuthell 2019).

Given the extensive costs associated with loyalty programmes in the financial services industry (for example, the South African programme eBucks claims to have paid out more than 3 billion rand in the last two years to customers (Businesstech 2021)) and the expected growth of the global loyalty management market from $8.6 billion in 2021 to $18.2 billion in 2026 (MarketsandMarkets 2021), the effectiveness of these programmes in terms of creating long-term value is of major importance. A critical aspect is the retention of existing customers, as the cost of acquiring new customers is five times more than retaining existing customers, with the development of customer relationships providing a competitive advantage in a very competitive market (Liljander et al 2009; Barney et al 2011; Fraering and Minor 2013; Estrella-Ramón, 2017; Hegner-Kakar et al 2018).

Stronger customer relationships and customer loyalty further impact the bottom line as a 5% decrease in customers leaving improves a bank’s profitability by between 2 and 8% (Khan and Fasih 2014; Belás and Gabčová, 2016). This direct relationship between customer loyalty and a bank’s profitability, claiming that if a Czech bank increased its loyal customers by 10,000, it would see an equivalent increase of 9.6mil EUR in profit, is challenged by research that has indicated that customer loyalty does not have a significant impact on the profitability of banks (Belás and Gabčová, 2016). This divergence of findings leads to a need for the development of a loyalty model which encapsulates customer relationships as an asset of the organisation and foundational to loyalty programme effectiveness. The historic market impacts of financial services on customer relationships and the requirement to build trust in an industry marked by its complexity of propositions (West et al 2013; Estelami 2015; Tabrani et al 2018) require loyalty programme design to be unique and differentiated in order to address these issues.

Loyalty programmes across industries have established partnerships to expand the variety of perceived benefit categories on programmes, with membership in these multipartner loyalty programmes or coalitions at 2.07 billion consumers in 2015, accounting for 28% of the world population (Finaccord 2015; Steinhoff and Palmatier 2016). The ability to differentiate loyalty programmes through partner propositions in the financial services industry also resulted in the establishment of many multipartner programmes, with the effect of these partnerships being questioned (Steinhoff and Palmatier 2016).

Loyalty programmes in the financial services industry have over the years expanded their benefit categories from initially only being monetary credit card-based benefits, to evolve into providing travel benefits in the form of miles accumulation, entertainment benefits including special events and access to musical events, as well as retail purchasing benefits sometimes implemented as cobrands, and also social benefits, where customers were enabled to donate to charities. Some key examples here are Citibank offering travel, student mortgage loan repayments, gift cards and charity benefits, Wells Forgo offering online auctions, travel, donating their points to the Red Cross charity and other individuals, and many more (Nemes 2022). With such a diverse portfolio of partner propositions and associated resource implications, it is thus of utmost importance to ensure that the influence of perceived benefit categories on long-term value for the financial services firm is taken into consideration when strategic loyalty programme partnerships are formed.

While the importance of loyalty programme effectiveness in terms of its ability to influence customer relationships and customer loyalty is apparent in an era of profitability pressures, increased competition and multipartner programmes, research in this context has been lacking. Research on loyalty programme effectiveness has predominantly been in the retail and travel industries (Mimouni-Chaabane and Volle 2010; Wang et al 2014; Chaudhuri et al 2019), where scale and pricing drive profitability. A lot of research has been done on customer loyalty in the financial services industry (Estrella-Ramón, 2017; Hegner-Kakar et al 2018; Mukerjee 2018; Özkan et al 2019), but very little research has been done on loyalty programme effectiveness as the research in this industry has to date been mostly based on single card product programmes (Leavell 2016).

This research examines the relationship between loyalty programme design elements and their ability to develop customer relationships and customer loyalty in the financial services industry, with both customer relationships and loyalty representing market-based assets that have been proven to drive shareholder value. A loyal customer base is a competitive asset for the firm and a major contributor to its equity (Meyer-Waarden 2015; Voorhees et al 2015; Estrella-Ramón, 2017). Customer loyalty is one dimension of the relational market-based assets of the organisation. In the context of the financial services industry, the research established the contribution of each category of perceived benefits, classified as: (a) monetary savings, (b) exploration, (c) entertainment, (d) recognition and (e) social benefits (Mimouni-Chaabane and Volle 2010) to customer relationships, which in turn result in customer loyalty.

The research further establishes the impact of both timing and type of rewards as moderators on the extent to which each perceived benefit category influence customer relationships and customer loyalty. Understanding the impact of context and moderating and mediating variables on the development of customer loyalty and ultimately loyalty programme effectiveness has become an important area of study (Meyer-Waarden 2015; Picon-Berjoyo et al 2016) with the importance of type and timing of rewards as moderating variables being widely acknowledged (Meyer-Waarden 2015). Some authors specifically called for the inclusion of these variables as moderators in future research (Dorotic et al 2012; Breugelmans et al 2015). The study also provides an understanding of the drivers for both behavioural and attitudinal loyalty, contributing to the evolution of the customer loyalty construct for the financial services industry.

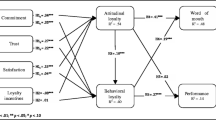

The study contributes to the literature on loyalty programme effectiveness in terms of: (a) extending the loyalty programme effectiveness framework developed by Wang et al (2014) to the financial services industry by establishing how loyalty programmes develop customer loyalty through relationships; (b) further refining this framework by introducing two moderating variables, namely type and timing of rewards as key design elements of loyalty programmes (Dowling and Uncles 1997); and (c) extending this framework by measuring customer loyalty in terms of both attitudinal and behavioural loyalty (Dick and Basu 1994; Puvendran 2016) (Fig. 1).

This represents a model of the contribution of this study to the body of knowledge. The theoretical model comprises loyalty programme design, customer relationship management and customer loyalty components. Adapted from “The antecedents and influences of airline loyalty programmes: the moderating role of involvement”, by Wang et al. (2014), Service Business, 9(2), p. 268. The enhancements of the model are indicated by the perforated construct containers

Literature review and hypotheses

The first loyalty programme launched by American Airlines in 1981 in the airline industry initiated the introduction of multiple loyalty programmes across industries, including programmes in financial services (Steinhoff and Palmatier 2016). The American Express Centurion card was one of the first programmes taken to market and is still today perceived to be the most exclusive card in the world, offering a wide array of perceived benefit categories and partners. These include experience benefits through travel and concierge, social benefits through gift cards and restaurants, exploration, recognition and monetary savings through points allocation, discounts and shopping benefits (Adams 2022).

The financial services industry, being a service industry, has a specific advantage over other industries in terms of its ability to develop customer loyalty through customer relationships. Customer orientation, customer empowerment, complaints handling and customer knowledge being dimensions of customer relationship strategies, have a direct and positive influence on customer loyalty and competitive advantage in the banking sector (Bhat and Darzi 2016). Customer relationships with financial institutions have a more intense emotive connection when customer loyalty is established than compared to relationships with customers who are merely satisfied with the services (Belás and Gabčová, 2016). This results in increased purchases and cross-sell as well as recommendations, as these customers tend to provide more information about themselves, enabling financial institutions to be more targeted in their propositions (Murugiah and Akgam 2015).

Historic low switching behaviours in the financial services industry (Van der Cruisjen and Diepstraten 2017) are being challenged by new digital entrants to the market (McKinsey & Company 2021). The resultant higher levels of price awareness and the associated loyalty programmes that aim to drive product take-up and spend raise concerns for consumer protection, specifically as the recent crises have placed the focus on social responsibility in the financial services industry (Belás and Gabčová, 2016). The development of customer loyalty through customer relationships is thus not only very relevant, but also very important in the financial services industry with value creation at the centre of design (Puustinen et al 2014). The definition adopted for loyalty programmes in this research aligns with those of Meyer-Waarden (2015), Dorotic (2012) and Meyer-Waarden (2008), as “an integrated system of marketing actions that aims to make customers more loyal by developing personal relationships with them” (Meyer-Waarden 2008: p. 89). Because the nature of the relationship between the financial institution and the customer is quite different to those in other industries, the relationship between customer perceived benefits and perceived relationship investment is expected to be different for the financial services industry.

The relationship between customer perceived benefits and perceived relationship investment

Loyalty programmes in the financial services industry have over the years expanded their benefit categories from initially only being monetary credit card-based benefits, to evolve into providing travel benefits in the form of miles accumulation, entertainment benefits through special events and access to musical events, retail purchasing benefits sometimes even implemented as cobrands, and social benefits where customers are enabled to donate to charities. Some examples of these diverse benefits being provided through some of the best multipartner loyalty programmes in the financial services industry are Citibank offering travel, student mortgage loan repayments, gift cards and charity benefits, and Wells Forgo offering online auctions, travel, donating their points to charities and other individuals, and many more (Nemes 2022).

Mimouni-Chabaane and Volle (2010) developed a five-factor scale grouping customer perceived benefits into categories, namely monetary savings, exploration, entertainment, recognition and social benefits. The effect and contribution of each of these benefit categories to perceived relationship investment for financial services is evaluated, with empirical evidence that customer perceived relationship investment influences relationship quality and ultimately customer loyalty in the banking sector (Balaji 2015). This is supported by the principle of reciprocity where an organisation’s efforts to build relationships result in reciprocal relationship quality and loyalty from the customer. Perceived benefits and value from a customer perspective are most important in the financial services industry (Baharun et al 2014), as the drivers of customer loyalty need to be established from this perspective (Ludin and Cheng 2016).

The quality of the customer’s relationship with the financial institution is affected by the customer’s perceived view of the firm’s investment in the relationship (Balaji 2015). Perceived relationship investment is defined as: “a consumer’s perception of the extent to which a retailer devotes resources, efforts, and attention aimed at maintaining or enhancing relationships with regular customers, that do not have outside value and cannot be recovered if these relationships are terminated” (Smith 1998: p. 79). This research interrogates the extent to which customers perceive the financial services firm to invest in a relationship with them.

The most important determinant of banking customers’ purchase behaviour and continued usage of products and services is fees and service charges (Unes et al 2019). Loyalty programmes in the financial services sector provide distinct benefits in terms of products and pricing to drive take-up, retention and usage. These benefits have a direct impact on the perceived pricing of the products. Some of the world’s best loyalty programmes offer extensive monetary benefits, one being Bank of America offering a 5% interest rate booster, mortgage reduction, no fees for select banking services, free ATM transactions per year and allows members to make free online stock and ETF trades (Nemes 2022). Barclays Blue Rewards offers up to 10% cash back on transactions made at more than 150 retailers, as well as cash back on debit payments, insurance, mortgage, loans and life insurance (Nemes 2022). As a result, the following hypothesis is proposed: Hypothesis 1a: Monetary savings directly affect perceived customer relationship investment in the financial services industry.

Exploration benefits satisfy the curiosity of customers, inform and expose them to products, services and knowledge to which they would not otherwise have had access (Wang et al 2014). These value-added informational benefits are intangible, difficult to replicate, provide access to exclusive promotions and opportunities to try new products (Mimouni-Chaabane and Volle 2010), and create an emotional bond with the customer (Saili et al 2012). Loyalty programmes within the financial industry continuously promote content to educate customers about current offers, and extend the brand’s online presence (Nemes 2022). With education and financial literacy being very important in the financial services industry (West et al 2013), the following hypothesis is proposed: Hypothesis 1b: Exploration benefits directly affect perceived customer relationship investment in the financial services industry.

Wells Fargo and Citibank are two of the many financial services loyalty programmes including entertainment benefits which are integrated in their value proposition (Nemes 2022). Because entertainment is an integral part of a customer’s lifestyle and a form of self-expression (Saili et al 2012) enabled through financial means, it is expected that entertainment benefits would positively affect perceived relationship investment in the financial services industry, and therefore, the following hypothesis is proposed: Hypothesis 1c: Entertainment directly affects perceived customer relationship investment in the financial services industry.

Recognising the customer on an emotional level can be less costly and very effective (Shaukat and Auerbach 2012), providing prestige (Ha and Stoel 2014) and achieved status (Drèze and Nunes 2009). Bank of America as an example recognises customers with an account balance of over 100,000 dollars with a Platinum Honours rank, giving them access to exclusive offers and reduced fees (Nemes 2022). As the financial services industry in general discriminates in terms of product offerings between segments in the market, the following hypothesis is proposed: Hypothesis 1d: Recognition directly affects perceived customer relationship investment in the financial services industry.

Social benefits are symbolic benefits which provide for the customer’s need for self-expression, social acceptance and self-esteem, while simultaneously enabling association and a sense of belonging based on shared values (Mimouni-Chaabane and Volle 2010). Social benefits on a loyalty programme create a source of identification and satisfies customers' needs to associate with something successful or desirable (Omar et al 2015). These social benefits enable the alignment of the programme value to the customers’ identity salience (Ha and Stoel 2014). Social responsibility is a focus area for financial institutions (Hernaus and Stojanovic 2015; Belás and Gabčová, 2016) to rebuild trust lost during financial crises, as virtual communities co-creating value have been effective in driving customer loyalty in this industry (Fraering and Minor 2013). Some loyalty programmes allow customers to form groups and contribute towards a shared goal, thereby building communities around their brand (Nemes 2022). Citibank, for example, allows customers to transfer points to other member’s accounts. The same can be done with charity events, where members can gift a reward to those who cannot afford it. Based on this, the following hypothesis is thus proposed: Hypothesis 1e: Social benefits directly affect perceived customer relationship investment in the financial services industry.

The relationship between perceived relationship investment and brand relationship quality

Brand relationship quality is a type of relationship quality and a composite construct. It represents the strength and depth of the relationship of the customer with a brand (Smit et al 2007) and converges to two dimensions: connection and partner quality (trust, personal commitment and love). Connection is defined as nostalgic and self-concept connection, passionate attachment and intimacy (Smit et al 2007). Partner quality depicts the way the customer has been treated by the brand or firm (Andersson and Ibegbulem 2017) and this perception is based on what the customer values and can associate with (Mimouni-Chaabane and Volle 2010).

Perceived relationship investment drives brand relationship quality (Mimouni-Chaabane and Volle 2010; Wang et al 2014; Balaji 2015). Firms’ investments in the creation of emotional bonds with customers lead to connection, attachment and association with the brand (Marinkovic and Obradovic 2015; Mukerjee 2018; Rambocas and Arjoon 2019). Brand connection is an important marketing element in the financial services industry, and as such, the following hypothesis is proposed: Hypothesis 2a: Perceived relationship investment directly affects connection in the financial services industry.

Relationship investment by the firm also translate into partner quality (the way the customer has been treated by the brand or firm) resulting in trust, satisfaction and commitment in the banking industry (Balaji 2015). With e-commerce companies such as Google, Amazon and Facebook introducing competing financial payment propositions and developing trust with customers, one would expect the financial services industry to invest into relationships that build trust (which is an element of partner quality) in order to differentiate their offering. The following hypothesis is thus proposed: Hypothesis 2b: Perceived relationship investment directly affects partner quality in the financial services industry.

The relationship between brand relationship quality and customer loyalty

The concept of customer loyalty is fundamental to marketing scholarship and provides practitioners with an asset enabling differentiation and long-term relationships (Balaji 2015; Kandampully et al 2015; Nyadzayo and Khajehzadeh 2016; Peña et al 2017). Loyal customers portray behaviours that drive firm profitability because: (a) customers are less attracted to competitor’s products (Mukerjee 2018); (b) customers are less price sensitive (Evanschitzky et al. 2012; Picon-Berjoyo et al 2016); (c) customers engage in repeat purchasing (Kumar et al. 2010a, b); and (d) customers have a favourable attitude and emotional connection with the brand which results in word-of-mouth referrals and future purchases (Sacui and Dumitru 2014). This research specifically focuses on customer loyalty to the company and the contribution to firm value in its capacity as a market-based asset.

Many authors have historically focused solely on behavioural loyalty, until customer loyalty was redefined as a multidimensional construct including both attitudinal and behavioural loyalty (Dick and Basu 1994). This multidimensional definition has become widely accepted (Fitzgibbon and White 2005; Hegner-Kakar et al 2018). The most dominant research in this area defines loyalty as a combination of attitudes and behaviours: “Customer loyalty is viewed as the strength of the relationship between an individual’s relative attitude and repeat patronage” (Dick and Basu 1994: p. 100).

Behavioural loyalty depicts repeat purchase which could be as a result of various reasons like habit formulation, convenience and barriers to exit, and is not necessarily connected to the customer’s attitude towards the brand (Fitzgibbon and White 2005). Attitudinal loyalty is a deep desire by the customer to maintain a relationship with a firm (Czepiel and Gilmore 1987) and thus relates directly to the relationship the customer has with the firm and the psychological preference and commitment to the brand (Mukerjee 2018). Repeat purchase alone (behavioural loyalty) does not constitute brand or company loyalty. Brand loyalty is defined as:

(1) The biased (i.e. non-random), (2) behavioural response (i.e. purchase), (3) expressed over time, (4) by some decision-making unit, (5) with respect to one or more alternative brands out of a set of such brands and (6) is a function of psychological (decision-making, evaluative) processes (Jacoby and Kyner 1973, p. 2).

From the definition, consumer brand loyalty contributes to several objectives set by loyalty programmes, namely repeat purchase, biased attitude and long-term positioning. The definition also positions brand loyalty as a relational construct with specific inclusions of competitive forces in terms of the decision-making process. Loyalty programmes in financial services that focus predominantly on behavioural loyalty do not leverage their programmes strategically to drive attitudinal loyalty effectively (Fitzgibbon and White 2005). Attitudinal loyalty is also found to be much more effective in driving cross-selling success as opposed to behavioural loyalty based on habit (Liu-Thompkins and Tam 2013).

Connection has a strong bearing on attitudinal loyalty, as it reflects the emotional desire of customers to maintain a relationship with a brand in addition to their transactional requirements. Strong emotional connections or psychological bonding between customers and the firm drive attitudinal loyalty (Baumann et al 2005; Hawkins and Vel 2013; Boateng and Narteh 2016). The following hypothesis is thus proposed: Hypothesis 3a: Connection directly affects attitudinal loyalty in the financial services industry.

Connection between the firm and the customer also drives repeat purchase behaviour and behavioural loyalty (McCall and Voorhees 2010). Financial and social bonding activities aimed at creating a connection with the customer have a significant and positive effect on behavioural loyalty in the financial services industry (Liang and Wang 2006; Hoang 2019), and the following hypothesis is therefore proposed: Hypothesis 3b: Connection directly affects behavioural loyalty in the financial services industry.

Partner quality relates to how the customer has been treated by the firm, which is very important in service industries (Smit et al 2007). It is closely linked to trust, being a major driver of customer loyalty in banks (Pentina et al 2013; Özkan et al 2019). Service quality and satisfaction have a significant and positive effect on the development of attitudinal loyalty in the financial services industry (Kumar et al 2010a, b; Marinkovic and Obradovic 2015; Ludin and Cheng 2016; Javed and Cheema 2017), and the following hypothesis is therefore proposed: Hypothesis 3c: Partner quality directly affects attitudinal loyalty in the financial services industry.

Perceived service quality and satisfaction, which are important aspects of partner quality, further have a significant and positive effect on behavioural loyalty (Al Chalabi and Turan 2017; Mukerjee 2018). Customer orientation, which influences customer engagement strategies and is an aspect of partner quality, also has a direct effect on behavioural loyalty (Bhat 2016). Satisfaction with service drives behavioural loyalty in the financial services industry (Jayathilake et al 2016; Javed and Cheema 2017), and the following hypothesis is therefore proposed: Hypothesis 3d: Partner quality directly affects behavioural loyalty in the financial services industry.

Moderating variables

This research includes the design elements type and timing of rewards, developed by Dowling and Uncles (1997), and utilised in empirical research on loyalty programme effectiveness (Park et al 2013; Yi and Jeon 2003). Rewards are differentiated by: (a) reward type being direct or indirect and (b) reward timing being immediate or delayed (Dowling and Uncles 1997).

Reward type Rewards can be firm specific and relate to the products and services of the firm itself (direct rewards), or unrelated to the firm’s products and services (indirect rewards) (Park et al 2013). Loyalty programmes build brand association and an emotional connection with the brand in cases where the rewards are aligned to the brand of the firm (direct rewards) (Roehm et al 2002). As a result, it is expected that rewards related to financial services—direct rewards—will have a more significant positive effect on the relationship between perceived benefits and perceived relationship investment in the financial services industry. When evaluating the individual perceived benefit categories, it is evident that some of the categories are not directly related to the products and services provided by financial institutions. Loyalty programmes form strategic partnerships to provide a wider range of perceived benefits (Yoo et al 2018), and the inclusion of these partners increases the adoption of these programmes (Yan and Cui 2015).

Switching value which relates to monetary savings provided by financial institutions, has a direct impact on commitment to the institution (Licata and Chakraborty 2009), as well as financial bonding with the customer (Liang and Wang 2006; Milan et al. 2018). Many financial institutions are though participating in coalitions estimated at 974.7 mil members globally, which indicates that monetary savings provided by the coalitions are accumulated across industries to create value (Klie 2011). It is thus expected that monetary rewards provided by financial institutions and partners both contribute to the value created in financial services loyalty programmes and that reward type will not moderate the relationship between monetary savings and perceived relationship investment. The following hypothesis is thus proposed: Hypothesis 4a1: Reward type does not moderate the relationship between monetary savings and relationship investment in the financial services industry.

As financial institutions adopted self-service banking enabled by digital channels that improves the customer experience and provide for exploration of additional products and services, the associated personalisation of the service had a direct and positive impact on customer loyalty (Sindwani and Goel 2015). The ability to explore and learn about banking products and services that are relevant to the customer thus drives direct value to the relationship (Islam and Akagi 2018), while the important role that financial knowledge and access to credit scores plays in decision-making has long been acknowledged (Collins-Taylor 2018). Financial services loyalty programmes aim to provide their customers with access to propositions that align with their lifestyle and expose them to relevant information through strategic partnerships. The recent Visa/Supervalu partnership is a key example (Checkout 2019). It is thus expected that both direct and indirect exploratory benefits provided by financial services loyalty programmes will be equally effective. The following hypothesis is thus proposed: Hypothesis 4a2: Reward type does not moderate the relationship between exploratory benefits and relationship investment in the financial services industry.

Many of the top ten banking loyalty programmes in the world has included bank-related entertainment or gaming to drive differentiation and customer relationship strength. One of these is Zions Bank’s “The Pay for A’s” lottery game where students can win cash prizes (Jablonska 2019). Major card services like Visa, Mastercard and Amex and top banking loyalty programmes provide entertainment benefits through partnering with hotel chains, car rental companies and concierge services (Klie 2011; Wittmore 2018). Financial services institutions also partner with airlines, hotels and concierge services organisations that provide unique experiences in order to provide these benefits to their customers. The following hypothesis is thus proposed: Hypothesis 4a3: Reward type does moderate the relationship between entertainment benefits and relationship investment in the financial services industry.

Customers expect special treatment and personalised services from their banks which recognise their value and the need for a long-term relationship (Hasan et al 2011; Dimitriadis 2011). Customers of banks further want to be recognised and included in the co-creation of products and services (Dean and Alhothali 2017). The need for recognition is further provided for in multiple financial service loyalty programmes providing specific recognition for financial wellness targets achieved. Wells Fargo provides bonuses for savings above a specific limit (Nautiyal 2020). Recognition rewards or benefits are also often provided for with vouchers and coupons or in the case of Bask Bank, 71,000 American Airline miles for opening a savings account (Martucci 2022). As both direct and indirect recognition benefits are available and incentivising behaviour within the financial services industry, it is expected that reward type will not moderate the relationship between recognition benefits and perceived relationship investment. The following hypothesis is thus proposed: Hypothesis 4a4: Reward type does not moderate the relationship between recognition benefits and relationship investment in the financial services industry.

Social bonding tactics are very important and drive customer perceived value and customer loyalty in the financial services industry (Milan et al 2018). These tactics are often included in loyalty programme design and provide benefits like events and opportunities to form part of a community of people belonging to the programme. It aims to create social bonds with customers which drives relationship quality and influence customer loyalty directly (Ponder et al 2016). Social bonding tactics can also be achieved through partner propositions like travel, dining and unique family experiences which are typically included in these programmes. Because these benefits can be derived from both the financial institute and the partner, the following hypothesis is proposed: Hypothesis 4a5: Reward type does not moderate the relationship between social benefits and relationship investment in the financial services industry.

Reward timing. Immediate rewards are used when the customer is not intrinsically motivated to develop a relationship with the firm and delayed rewards for customers in markets marked by variety-seeking behaviour (Yi and Jeon 2003; Dorotic et al 2012). Delayed rewards were found to be more effective in building customer loyalty in cases where customer satisfaction existed for the service (Leavell 2016).

Because of the increase in digitisation and the variety-seeking nature of the younger population, new card programmes like the Apple Card provides for 2% daily cash back (Apple 2020). As such, the following hypothesis is proposed: Hypothesis 4b1: Reward timing moderates the relationship between monetary savings and relationship investment in the financial services industry.

Exploratory, entertainment, recognition and social benefits are all activated based on customer choice and convenience and for that reason the following hypotheses are proposed: Hypothesis 4b2: Reward timing does not moderate the relationship between exploratory benefits and relationship investment in the financial services industry; Hypothesis 4b3: Reward timing does not moderate the relationship between entertainment and relationship investment in the financial services industry; Hypothesis 4b4: Reward timing does not moderate the relationship between recognition and relationship investment in the financial services industry; Hypothesis 4b5: Reward timing does not moderate the relationship between social benefits and relationship investment in the financial services industry.

Methodology

Respondents were sourced from a market research company, P-Cubed, which owned the largest established commercial consumer database in South Africa. The research needed to provide insights on financial service loyalty programmes in general and not be specific to a particular program. P-Cubed provided 2700 fields of data on over 33 million economically active consumers in South Africa. This research adopted a two-staged sampling approach where Stage 1 consisted of simple random sampling (the pilot), and Stage 2 of stratified random sampling. Respondents were required to have enrolled for a financial service loyalty programme and were requested to complete the survey in relation to the financial service loyalty programme they enrolled for.

Criteria for selection in Stage 1 included: (a) high probability of a valid e-mail address, (b) no previous opting out from P-Cubed communication and (c) no previous opting out from the South African Direct Marketing Association database. These criteria ensured that the survey distribution process via email was effective and not in contravention with data privacy legislation. Stage 2 eliminated respondents who were younger than 18 and older than 60 years of age, due to limited valid email addresses for these age groups, as well as contact details for people who had died. Stratified random sampling was used where the opportunity for the selection of male and female respondents across all financial affluence segments was equal. Each financial affluence segment was given equal weighting. An equal number of male and female respondents per financial affluence segment was selected. The selection process ensured that both male and female as well as all affluent segments were adequately represented in the findings.

The target number of respondents was 266 as the questionnaire consisted of 38 questions, and the research sought to achieve seven to eight respondents per survey question for statistical relevance (Zikmund et al 2010). This is in line with sample size requirements for Structural Equation Modelling (SEM), which measures sample size requirements of more than 200 or five to 20 times the variables (Lei and Wu 2007). The sample size is further supported by Hair (2014), indicating a requirement of five respondents per item. As the model consisted of 36 items, 180 respondents would have been sufficient. Only respondents belonging to a financial service loyalty programme were included in the analysis.

Data analysis

Descriptive analysis was conducted on all constructs and their items. Levene’s test was done to test for age non-response bias. Common bias was tested for, and both the reliability and validity of the measurement scales were assessed, which was followed by SEM. SEM comprised two stages, namely (a) the development of a measurement model using confirmatory factor analysis (CFA) (model estimation) and (b) the development of the structural model (model evaluation). Robustness testing was then done to assess whether the estimated effects on the dependent variables (perceived relationship investment, partner quality, connection, behavioural loyalty and attitudinal loyalty) were sensitive to changes in model specifications. According to Neumayer and Plümper (2017), there are five types of robustness tests, namely (1) model variation test, (2) randomised permutation test, (3) structured permutation test, (4) robustness limit test and the (5) placebo test. For this study, the model variation test was preferred because of its simplicity.

The concept of moderation refers to a significant change of a structural relationship in terms of strength and/or direction across the levels of a third variable called a moderator (Field 2013). Two common methods are used to test moderation, namely the interaction method and the multigroup difference method commonly called “invariance test” (Singh and Srivastava 2018). Two reasons motivated the choice of the multigroup difference method; firstly, the growing popularity of the technique in testing categorical moderators (Hakim et al 2020; da Cunha et al. 2020; Thuy Hang Dao and Von der Heidt 2018), secondly, the only plugin (multigroup) available to test moderation in the Amos 26 environment essentially uses the multigroup difference approach (Gaskin and Lim 2016). This method was thus selected for the study.

Operationalisation of the construct measures

Type and timing of reward (Dowling and Uncles 1997). The respondents were given the opportunity to advise their preferences in terms of the type and timing of rewards. This was then related to the perceived benefits of the programme and their effect on perceived relationship investment. Both type of rewards and timing of rewards as developed by Dowling and Uncles (1997) having been utilised in several studies, with specific reference to Yi and Jeon (2003) in terms of their measurement of customer loyalty (Table 1).

Customer perceived benefits (Mimouni-Chaabane and Volle 2010). Customer perceived benefits were measured by utilising the five dimensions or categories developed by Mimouni-Chabaane and Volle (2010), namely (a) monetary savings, (b) exploration, (c) entertainment, (d) recognition and (e) social, with each benefit dimension measured by three items. Some questions were adapted for the financial services industry as the original construct measurement was designed for the retail sector.

Perceived relationship investment (De Wulf et al. 2001). Perceived relationship investment was measured according to the scales developed by De Wulf et al. (2001) and adapted for the financial services industry. This scale is still being used by multiple authors (Wang et al. 2014).

Brand relationship quality (Smit et al. 2007). Brand relationship quality was measured according to the scales developed by Smit et al. (2007) and comprised of two dimensions: (a) connection and (b) partner quality, which were adapted for the financial services industry. This scale is still being used by multiple authors for very recent research (Wang et al. 2014).

Customer loyalty (Bennett and Rundle-Thiele 2002; Chaudhuri and Holbrook 2001; Kumar et al 2010a, b; Sirdeshmukh et al. 2002). Customer loyalty was measured according to the scales developed by Sirdeshmukh et al. (2002), in terms of behavioural (four items) and attitudinal loyalty (five items). These scales are still being used by multiple authors for very recent research (Kim et al. 2013) and were adapted for the financial services industry for this research.

Results

In total, 392 responses were received of which 25 were rejected since the respondents did not belong to a loyalty programme, 49 responses were incomplete, and 41 respondents were not members of a financial services industry loyalty programme, leaving 277 respondents, which exceeded the required sample size of 266. Most respondents who participated in this research study were between the ages of 31 and 60 (85.9%), with the largest number of respondents being between 31 and 40 years old (36.2%). The respondents adequately represented all age groups and the female and male distribution was very similar to the overall employment statistics in South Africa, with 49.4% being male and 50.6% female (Statistics South Africa 2017).

Descriptive analysis on all constructs and their items

These results indicate that the respondents agreed in general with the statements made for perceived relationship investment, entertainment, partner quality, behavioural loyalty and attitudinal loyalty (average score above 3.5), where they were neutral about the remainder (average score between 2.5 and 3.5) (Table 2).

Control for age non-response bias

Levene’s test was used to determine whether any age non-response bias was observed and confirmed non-response bias for all age groups.

Control for common method bias

For a survey-based cross-sectional study, it is advisable to control and test for common method bias. The total variance shared among the 36 items only accounted for 44.04%, which is below 50%. This result suggests that common bias did not affect the data; hence, the results obtained in this study are valid.

Measurement model

Due to the quality of the pilot study, no further improvements were required in terms of the measurement model fit.

Reliability, convergent and discriminant validity assessment

Table 3 indicates that the Cronbach’s alpha coefficient values for the measurement scales measuring the constructs of this research study all exceeded 0.70, which indicates good internal consistency reliability (Malhotra et al. 2009). The convergent validity of all the scales was also good given that all the AVEs were above 0.5. Convergent validity means that the instruments used are appropriate. Although there is a minor concern regarding the discriminant validity (0.682 > 0.625) of behavioural loyalty, the discriminant validity of the rest of the scales were good. Since discriminant validity was supported, we can conclude that each construct in the measurement model adequately measured a different concept. Confirmatory factor analysis further confirmed the item loadings to the relevant constructs.

Correlation estimates between constructs

Table 4 indicates an overall acceptable level of correlations between all the constructs as all correlation estimates were less than 0.8 (Hair et al 2014), except for the correlation between behavioural loyalty and attitudinal loyalty. This is consistent with discriminant validity results found earlier and in line with theory indicating a causal relationship between attitudinal and behavioural loyalty (Dick and Basu 1994), indicating that relationship building strategies drive attitudinal loyalty that results in repeat purchase or behavioural loyalty in the financial services industry (Fitzgibbon and White 2005). The table clearly indicates that almost all the correlations are significant at 99% confidence interval (Table 4).

Measure model fit analysis

The Chi-square of the measurement model was 2.172, indicating a good fit as it is smaller than 3. The degrees of freedom here were 548 with a p value of 0.000, indicating significance at 99% level. The comparative fit index (CFI) at 0.826 indicated “sometimes acceptable”, which made the other indices and their values important in motivating the final fit for the model. Goodness-of-fit index (GFI) at 0.928 and TLI at 0.917 both exceeded the recommended cut-off point of 0.90 indicating a good measurement model fit (Hair et al 2014). The root mean square error approximation (RMSEA) of 0.061 was higher than the recommended cut-off point of 0.05, indicating a moderate model fit (Hair et al 2014). The measurement model indices thus indicate a moderate fit in terms of RMSEA and CFI indices and a good fit in terms of Chi-square, GFI and TLI indices. An acceptable to good fit of the measurement model was thus established. It was therefore concluded that the measurement model adequately represents the observed data.

Structural model

A model fit diagnosis was conducted based on the modification indices and the standardised residual covariance matrix (Byrne 2010). The results of the model fit diagnosis indicated that additional significant relationships were missing in the model. These additional relationships were therefore added to improve the model fit. According to the finding, these new paths exist in the financial services industry, and ignoring them would make the model inaccurate. These additional relationships were therefore added to improve the model fit and supported by relevant theory as below. However, it is suggested that further studies should investigate these new paths in other industries.

Unlike the other relationships suggested, these relationships were added in sequence of priority, because there was statistical evidence that they contribute to the model fit and were supportive and consistent with the main theories used. These new paths further enhance the academic contribution made by this research. As relationship loyalty programmes are taking hold within the financial services industry, points accumulate faster as consumers use social media applications to build and strengthen their personal relationships by bringing banking into their social circles. Perceived relationship investment is the result of financial and social bonding activities, creating a connection with the customer which has a significant and positive effect on behavioural loyalty in the financial services industry (Liang and Wang 2006) and has been further supported by research in the retail industry (Meyer-Waarden 2008).

Even though digital technology tends to overexpose customers to options and choice, the quality of information shared and the support provided are critical in the perception of how the customer is being treated and have been proved to increase customer loyalty (Ludin and Cheng 2016).

Structural model fit indices

The Chi-square of the structural model was 33.485, degrees of freedom 17 and its p value 0.010, at a significance level of 99%. The Chi-square index indicates good structural model fit with the observed data. The GFI index measured at 0.980, the CFI index at 0.991 and the TLI index at 0.976, all indicating a good fit and exceeding the 0.9 threshold (Hair et al 2014). These values exceeded those obtained in the measurement model, which were GFI index of 0.928, CFI index of 0.826 and a TLI index of 0.917, indicating that the structural model displays a better fit than the measurement model to the observed data. The RMSEA index at 0.55 indicates a moderate model fit and is slightly lower than the measure obtained in the measurement model (0.061). The structural model fit to the observed data is thus adequate to good, and the model may be used with confidence to draw conclusions on the research hypotheses.

Social benefits were the strongest predictor of perceived relationship investment, followed by exploration, monetary and entertainment benefits. All four predictors together had the potential to improve perceived relationship investment by up to 39%. Perceived relationship investment was the strongest predictor of partner quality; however, together with social benefits and exploration, these predictors have the potential to improve partner quality by up to 43%. The social benefits category was the strongest predictor of connection; however, together with perceived relationship investment, these predictors have the potential to improve connection by up to 48%. Connection was the strongest predictor of behavioural loyalty; however, together with partner quality and perceived relationship investment, these predictors have the potential to improve behavioural loyalty by up to 51%. Partner quality was the strongest predictor of attitudinal loyalty; however, together with connection and perceived relationship investment, these predictors have the potential to improve attitudinal loyalty by up to 67%. The findings here indicate that the drivers of attitudinal loyalty and behavioural loyalty differ, providing insights into managerial strategies to drive not only repeat purchase but also brand loyalty.

Moderation analyses

The multigroup difference approach of testing moderation consists of three principal phases (Singh and Srivastava 2018; Gaskin and Lim 2016). (1) Identify the levels (subgroups) of the moderator; in this case, each moderator has two groups because both moderators are dichotomous. (2) Test the conceptual model for each subgroup. For example, Figs. 2 and 3 display the results of the tested model for both subgroups of the moderator “reward time”. (3) Compare the strength, direction and level of significance of each the relationship between the subgroups to determine whether moderation has occurred or not. Any significant difference suggests a moderation while a non-significant difference indicates an absence of moderation (Gaskin and Lim 2016). The results of this last phase are summarised in Table 5 (reward timing) and Table 6 (reward type).

Timing of reward The SEM models for both immediate and delayed rewards were developed and are presented below (Figs 2, 3).

The results of the multigroup difference moderation analysis for timing of reward are presented below in Table 5:

According to the results, the relationship between monetary savings and perceived relationship investment is significantly stronger among customers who prefer immediate rewards compared to those who prefer delayed rewards (p < 0.1). In contrast, the relationship between Exploration benefits and Perceived Relationship Investment is significantly weaker among customers who prefer immediate reward compared to those who prefer delayed reward (p < 0.05). Hence, the conclusion that “reward time” moderates these two relationships. No other moderation was found in the data; therefore, we submit that the strength and the significance of these other relationships do not differ between customers who prefer immediate reward and those who prefer delayed reward (p > 0.05).

Type of reward The SEM models for both direct and indirect rewards were developed and are presented below (Figs. 4, 5).

The results of the multigroup difference moderation analysis for rewards type are presented below in Table 6.

The results of the grouped analysis for reward type indicated that reward type does not moderate the relationships of monetary savings, recognition and social benefits with perceived relationship investment (p > 0.05). The relationship between both exploration benefits and entertainment benefits and perceived relationship investment are significantly stronger among customers that prefer indirect rewards compared to those that prefer direct rewards (p < 0.05). Reward type thus moderates the relationships of exploration benefits and entertainment benefits with perceived relationship investment.

Robustness testing

The baseline model below without the moderating variables and the attitudinal loyalty construct was compared to the proposed model (Fig. 6).

The model variation robustness test is the simplest approach as it compares the proposed model with the baseline model. In this case, the R2 of the baseline model was compared with the R2 of the proposed model (which includes attitudinal loyalty and the two moderating variables type of reward and timing of reward). The result of the robustness test is provided in Table 7.

The proposed conceptual model was found to be more robust than the baseline model as it explains the greater amount of variance in the dependent variable.

The outcomes of the various hypotheses are summarised in Table 8.

Discussion

Due to customer-driven financial outcomes in the financial services industry, the development of customer loyalty and customer relationships have become important differentiators (Hegner-Kakar et al. 2018). A key finding of this study is the importance of social benefits in driving customer relationships in the financial services industry. Social benefits, followed by exploratory benefits, then monetary savings and lastly entertainment benefits, significantly predict perceived relationship investment for loyalty programmes in the financial services industry. This finding provides a major opportunity for financial services to reduce the cost of their loyalty programmes by replacing some of the monetary benefits with much more effective social and exploration benefits. Recognition made no significant contribution.

Furthermore, as a new path for this industry, social benefits were found to be a new unique predictor of partner quality (the way the customer has been treated by the firm), indicating that a loyalty programme design with strong social benefits creates strong perceptions in the customer’s mind about how the customer is being treated by the firm and is thus an influencer of customer experience. Partner quality relates to trust, personal commitment and love (Smit et al. 2007). Social benefits which provide for the customer’s need for self-expression, social acceptance and self-esteem (Keller 1993), significantly contributed to partner quality, building trust, personal commitment and love and were also the strongest predictor of connection, with perceived relationship investment the other significant predictor.

This was to be expected, given that brand image connection with a customer revolves around identification with the brand (Hawkins and Vel 2013; Wang et al 2014). This finding clearly highlights the ability of social benefits on the loyalty programme to drive customer relationships (Hennig-Thurau et al 2000). The relationship between exploration and partner quality implies that by increasing exploration benefits, partner quality will decrease. This finding is in support of customers wanting to be able to find (or be offered) personalised propositions and services easily and conveniently (Cedrola and Memmo 2010), and they want to be treated fairly and adequately by the firm (Saili et al 2012).

The drivers for attitudinal and behavioural loyalty differs in the financial services industry. Connection (association with the brand) is the strongest predictor of behavioural loyalty, followed by partner quality and perceived relationship investment. This finding supports the view that emotional attachment with the brand drives repeat purchase. Partner quality is the strongest predictor of attitudinal loyalty and should be leveraged as such. This study found that connection and perceived relationship investment (new path for financial services industry) together with partner quality have the potential to improve attitudinal loyalty by up to 67%. The way in which customers are treated thus has a significant influence on the emotional attachment of the customer to the brand and is critical in order to sustain the financial success of the programme (Marinkovic and Obradovic 2015).

Timing of reward was found to moderate the relationship between monetary and exploratory benefits and perceived relationship investment. Exploratory benefits, being a strong predictor of perceived relationship investment, had a stronger effect on perceived relationship investment among respondents who preferred delayed rewards, where monetary savings had a stronger effect on perceived relationship investment among respondents who preferred immediate rewards. This provides clear guidance to financial institutions in terms of timing for their monetary benefit and exploratory benefit design. Reward timing had no significant effect on the relationship of other categories of benefits with perceived relationship investment.

Type of reward was found to moderate both the relationships of entertainment and exploration benefits with perceived relationship investment. Exploration and entertainment, being strong predictors of perceived relationship investment, had a stronger effect on perceived relationship investment among respondents who preferred indirect rewards.

Conclusion

Taking into consideration the significant investment financial institutions are making when launching a loyalty programme, care should be taken that the programme effectively develops assets in the form of customer loyalty and relationships that drive future revenues. The loyalty programme thus needs to be designed such that these objectives are achieved. Financial services loyalty programmes, like loyalty programmes in other industries, have over time enhanced their value proposition by partnering with retailers, airlines, telecommunication institutions and various entertainment providers (Breugelmans et al 2015). The value of these benefits to customers and the firm is questioned (Dorotic et al 2021). This research provides valuable insights into design elements of an effective loyalty programme in the financial services industry developing market-based assets and driving long-term value for the firm. While many programmes focus predominantly on monetary benefits, these programmes need to include a focus on social benefits augmented by exploratory benefits to drive deeper customer relationships. As monetary benefits are costly, this should enable firms to improve their return on investment. These programmes need to foster brand association through social benefits that relate to the unique experience of ownership and utilisation of the financial products, which integrate with family, communities and, for example, education. The inclusion of exploration benefits provides the opportunity for these programmes to expose consumers to new generation financial services integrated with social impact. This will enable financial institutions to build emotional connections and trust (Marinkovic and Obradovic 2015) that fuel customer relationships and ultimately customer loyalty. Recognition has been found to have no significant impact on customer relationships and such benefits will not have a material impact on success.

The loyalty programme design category findings in this research provide clear guidance to these institutions on how to develop and run effective programmes delivering long-term value and competitive advantage. Financial service loyalty programmes should also consider customer’s preference in terms of the timing of rewards and reward type. Perceived relationship investment is significantly enhanced by monetary rewards for customers that prefer immediate rewards and exploratory rewards enhances perceived relationship investment in cases where customers prefer delayed rewards. Where customers prefer indirect or partner rewards, perceived relationship investment is increased through partners providing entertainment and exploratory benefits.

Valuable insights into the drivers of behavioural and attitudinal loyalty are also provided. Behavioural loyalty or repeat purchase is strongly influenced by connection, which is brand association. Loyalty programmes in financial services should thus not merely incentivise repeat purchase, but strategically build an attachment to the brand to enable sustainable long-term benefit to the firm. Attitudinal loyalty is strongly influenced by partner quality, which is the way in which the customer has been treated by the firm. Loyalty programmes in this industry thus need to pay close attention to the overall service quality for the financial services institution, as customers perceive product offerings and service holistically and the effectiveness of the loyalty programme’s ability to develop attitudinal loyalty is dependent on the overall customer service quality.

References

Acharya, V.V. (2013) Understanding Financial Crises: Theory and Evidence from the Crisis of 2007–2008. New York, USA: NYU Stern School of Business. Working Paper.

Adams, D. (2022) American Express Centurian Black Card 2022 Review. Forbes Advisor, 31 January, https://www.forbes.com/advisor/credit-cards/reviews/centurion-from-american-express/, accessed 26 January 2022.

Andersson, G., Ibegbulem, A. 2017. Managing customer loyalty in the digital era of the banking industry. Master thesis, Department of Business Studies, Uppsalal University, Sweden.

Apple. 2020. A simple, smarter credit card, Apple Card. https://www.apple.com/apple-card/features/. Accessed 26 Jan 2022.

Baharun, R., N.H. Hashim, and N.Z. Sulong. 2014. Exploring the relationship between benefit, satisfaction and loyalty among unit trust’s retail investors. World Applied Sciences Journal 31 (4): 439–443.

Balaji, M.S. 2015. Investing in customer loyalty: The moderating role of relational characteristics. Service Business 9 (1): 17–40.

Barney, J.B., D.J. Ketchen, and M. Wright. 2011. The future of resource-based theory: Revitalization or decline? Journal of Management 37 (5): 1299–1315.

Baumann, C., S. Burton, and G. Elliott. 2005. Determinants of customer loyalty and share of wallet in retail banking. Journal of Financial Services Marketing 9 (3): 231–248.

Belás, J., and L. Gabčová. 2016. The relationship among customer satisfaction, loyalty and financial performance of commercial banks. E a M: Ekonomie a Management 19 (1): 132–147.

Bennett, R., and S. Rundle-Thiele. 2002. A comparrison of attitudinal loyalty measurement approaches. Brand Management 9 (3): 193–209.

Bhat, S.A., and M.A. Darzi. 2016. Customer relationship management: An approach to competitive advantage in the banking sector by exploring the mediational role of loyalty. International Journal of Bank Marketing 34 (3): 388–410.

Boateng, S.L., and B. Narteh. 2016. Online relationship marketing and affective customer commitment - The mediating role of trust. Journal of Financial Services Marketing 21 (2): 127–140.

Breugelmans, E., T.H. Bijmolt, J. Zhang, L.J. Basso, M. Dorotic, P. Kopalle, A. Minnema, W.J. Mijnlieff, and N.V. Wünderlich. 2015. Advancing research on loyalty programs: A future research agenda. Marketing Letters 26 (2): 127–139.

Businesstech. 2021. eBucks scoops two awards at the 2021 South African loyalty awards for the 3rd year running. Businesstech, 8 December, https://businesstech.co.za/news/industry-news/545094/ebucks-scoops-two-awards-at-the-2021-south-african-loyalty-awards-for-the-3rd-year-running/. Accessed 28 Mar 2022.

Byrne, B.M. 2010. Structural equation modelling with AMOS: Basic concepts, application and programming. New York: Taylor & Francis Group.

Cedrola, E., and S. Memmo. 2010. Loyalty marketing and loyalty cards: A study of the Italian market. International Journal of Retail & Distribution Management 38 (3): 205–225.

Al Chalabi, H.S.A., and A. Turan. 2017. The mediating role of perceived value on the relationship between service quality, destination image, and revisit intention: Evidence from Umbul Ponggok, Klaten Indonesia. Global Business and Management Research: An International Journal 9 (4): 37–67.

Chaudhuri, A., and M.B. Hoibrook. 2001. The chain of effects from brand trust and brand affect to brand performance: The role of brand loyalty. Journal of Marketing 65 (April): 81–93.

Chaudhuri, M., C.M. Voorhees, and J.M. Bech. 2019. The effects of loyalty program introduction and design on short- and long-term sales and gross profits. Journal of the Academy of Market Science 47: 640–658.

Checkout. 2019. SuperValu partners with Visa for new loyalty program. 11 November, https://www.checkout.ie/retail/supervalu-partners-visa-new-loyalty-programme-82332. Accessed 26 Jan 2022.

Collins-Taylor, C. 2018. Young consumers challenge conventional wisdom on customer loyalty. Tellervision December (1496).

Czepiel, J.A., and R. Gilmore. 1987. Exploring the concept of loyalty in services. In The services challenge: Integrating for competitive advantage, ed. J.A. Czepiel, C.A. Congram, and J. Shanahan, 91–94. Chicago: American Marketing Association.

Dean, A., and G.T. Alhothali. 2017. Enhancing service-for-service benefits: Potential opportunity or pipe dream? Journal of Service Theory and Practice 27 (1): 193–218.

Deloitte. 2022. 2022 banking and capital markets outlook. Deloitte Centre for Financial Services, https://www2.deloitte.com/content/dam/insights/articles/US164678_CFS-banking-and-capital-markets-outlook/DI_CFS-banking-and-capital-markets-outlook.pdf. Accessed 26 Mar 2022.

Dick, A.S., and K. Basu. 1994. Customer loyalty: Toward an integrated conceptual framework. Journal of the Academy of Marketing Science 22 (2): 99–113.

Dimitriadis, S. 2011. Customers’ relationship expectations and costs as segmentation variables: Preliminary evidence from banking. Journal of Services Marketing 25 (4): 294–308.

Dorotic, M., T.H.A. Bijmolt, and P. Verhoef. 2012. Loyalty programmes: Current knowledge and research directions. International Journal of Management Reviews 14: 217–237.

Dorotic, M., D. Fok, P.C. Verhoef, and T.H. Bijmolt. 2021. Synergistic and cannibalization effects in a partnership loyalty program. Journal of the Academy of Marketing Science 49 (5): 1021–1042.

Dowling, G., and M. Uncles. 1997. Do customer loyalty programs really work? Sloan Management Review Summer 199: 71–82.

Drèze, X., and J.C. Nunes. 2009. Feeling superior: The impact of loyalty program structure on consumers’ perceptions of status. Journal of Consumer Research 35 (6): 890–905.

Du, T.G., Cuthell, K. 2019. As retail banks leak value, here’s how they can stop it. Bain & Company Report, 18 November 2019, https://www.bain.com/insights/as-retail-banks-leak-value-heres-how-they-can-stop-it/. Accessed 26 Jan 2022.

Estelami, H. 2015. Cognitive catalysts for distrust in financial services markets: An integrative review. Journal of Financial Services Marketing 20 (4): 246–257.

Estrella-Ramón, A. 2017. Explaining customers’ financial service choice with loyalty and cross-buying behaviour. Journal of Services Marketing 31 (6): 539–555.

Evanschitzky, H., B. Ramaseshan, D.M. Woisetschläger, V. Richelsen, M. Blut, and C. Backhaus. 2012. Consequences of customer loyalty to the loyalty program and to the company. Journal of the Academy of Marketing Science 40 (5): 625–638.

Field, A. 2013. Discovering statistics using IBM SPSS statistics, 4th ed. London: Sage Publications Ltd.

Finaccord. 2015. Global coalition programs. Finaccord Press Release, 24 August, https://www.finaccord.com/Home/About-Us/Press-Releases/8-24-2015-12-00-00-AM. Accessed 26 Jan 2022.

Fitzgibbon, C., and L. White. 2005. The role of attitudinal loyalty in the development of customer relationship management strategy within service firms. Journal of Financial Services Marketing 9 (3): 214–230.

Fraering, M., and M.S. Minor. 2013. Beyond loyalty: Customer satisfaction, loyalty, and fortitude. Journal of Services Marketing 27 (4): 334–344.

Gaskin, J., and Lim, J. 2016. Model fit measures. AMOS Plugin, Gaskination’s StatWiki.

Ha, S., and L. Stoel. 2014. Designing loyalty programs that matter to customers. The Service Industries Journal 34 (6): 495–514.

Hair, J.F., W.C. Black, B.J. Babin, and R.E. Anderson. 2014. Multivariate data analysis, 7th ed. Upper Saddle River: Pearson Education.

Hakim, M.P., L.D.A. Zanetta, J.M. de Oliveira, and D.T. da Cunha. 2020. The mandatory labeling of genetically modified foods in Brazil: Consumer’s knowledge, trust, and risk perception. Food Research International 132: 109053.

Hasan, S.A., M.I. Subhani, and S. Raheem. 2011. Measuring Customer Delight: A Model for Banking Industry. European Journal of Social Sciences 22 (4): 510–518.

Hawkins, K., and P. Vel. 2013. Attitudinal loyalty, behavioural loyalty and social media: An introspection. The Marketing Review 13 (2): 125–141.

Hegner-Kakar, A.-K., N.F. Richter, and C.M. Ringle. 2018. The customer loyalty cascade and its impact on profitability in financial services. In Partial least squares structural equation modeling: Recent advances in banking and finance, vol. 267, ed. N.K. Avkiran and C.M. Ringle, 53–75. Switzerland: Springer.

Hennig-Thurau, T., K.P. Gwinner, and D.D. Gremler. 2000. Why customers build relationships with companies - And why not. In Relationship marketing, ed. T. Hennig-Thurau, K.P. Gwinner, and D.D. Gremler, 369–439. Berlin: Springer.

Hernaus, A.I., and A. Stojanovic. 2015. Determinants of bank social responsibility: Case of Croatia. E a M: Ekonomie a Management 18 (2): 117–134.

Hoang, D.P. 2019. The central role of customer dialogue and trust in gaining bank loyalty: An extended SWICS model. International Journal of Bank Marketing 37 (3): 711–729.

Islam, K.A., and C. Akagi. 2018. An exploratory study of customers’ experiences with their financial services’ customer education programs as it impacts financial firm customer loyalty. Services Marketing Quarterly 39 (4): 330–344.

Jablonska, D. 2019. Top 10 bank’s loyalty programs in the world. Divante, https://divante.com/blog/top-10-banks-loyalty-programs-world/. Accessed 27 Jan 2022.

Jacoby, J., and D.B. Kyner. 1973. Brand loyalty vs. repeat purchasing behavior. Journal of Marketing Research X (February): 1–9.

Javed, F., and S. Cheema. 2017. Customer satisfaction and customer perceived value and its impact on customer loyalty: The mediational role of customer relationship management. The Journal of Internet Banking and Commerce 22 (S8): 1–14.

Jayathilake, N., N. Abeysekera, D. Samarasinghe, and J.L. Ukkwatte. 2016. Factors affecting for customer loyalty in Sri Lankan banking sector. International Journal of Marketing and Technology 6 (4): 148–167.

Kandampully, J., T. Zhang, and A. Bilgihan. 2015. Customer loyalty: A review and future directions with a special focus on the hospitality industry. International Journal of Contemporary Hospitality Management 27 (3): 379–414.

Keller, K.L. 1993. Conceptualizing, measuring, and managing customer-based brand equity. Journal of Marketing 57 (1): 1–22.

Khan, M.M., and M. Fasih. 2014. Impact of service quality on customer satisfaction and customer loyalty: Evidence from banking sector. Pakistan Journal of Commerce and Social Sciences 8 (2): 331–354.

Kim, H.Y., J.Y. Lee, D. Choi, J. Wu, and K.K. Johnson. 2013. Perceived benefits of retail loyalty programs: Their effects on program loyalty and customer loyalty. Journal of Relationship Marketing 12 (2): 95–113.

Klie, L. 2011. Global coalition loyalty program membership to top 1 billion in 2011. Destination CRM, 25 February, https://www.destinationcrm.com/Articles/ReadArticle.aspx?ArticleID=74045. Accessed 27 January 2022.

Kumar, S.A., B. Mani, S. Mahalingam, and M. Vanjikovan. 2010a. Influence of service quality on attitudinal loyalty in private retail banking. IUP Journal of Management Research 9 (4): 21–38.

Kumar, V., L. Aksoy, B. Donkers, R. Venkatesan, T. Wiesel, and S. Tillmanns. 2010b. Undervalued or overvalued customers: Capturing total customer engagement value. Journal of Service Research 13 (3): 297–310.

Leavell, J.P. 2016. Point redemption matters: A response to Murthi et al. (2011). Journal of Financial Services Marketing 21 (4): 298–307.

Lei, P.W., and Q. Wu. 2007. Introduction to structural equation modeling: Issues and practical considerations. Educational Measurement: Issues and Practice 26 (3): 33–43.

Liang, C.-J., and W.-H. Wang. 2006. The behavioural sequence of the financial services industry in Taiwan: Service quality, relationship quality and behavioural loyalty. The Service Industries Journal 26 (2): 119–145.

Licata, J.W., and G. Chakraborty. 2009. The effects of stake, satisfaction, and switching on true loyalty: A financial services study. International Journal of Bank Marketing 27 (4): 252–269.

Liljander, V., P. Polsa, and K. Forsberg. 2009. Do mobile CRM appeal to loyalty program customers? A study of MIDlet application offerings. In Emergent strategies for e-business processes, services, and implications: Advancing corporate frameworks, ed. I. Lee, 59–76. IGI Global: Western Illinois University, USA.

Liu-Thompkins, Y., and L. Tam. 2013. Not all repeat customers are the same: Designing effective cross- selling promotion on the basis of attitudinal loyalty and habit. Journal of Marketing 77 (September): 21–36.

Ludin, I.H., and B.L. Cheng. 2016. Factors Influencing customer satisfaction and e-loyalty: Online shopping environment among the young adults. Management Dynamics in the Knowledge Economy 2 (3): 462–471.

Malhotra, N.K. 2009. Marketing research: An applied orientation, 6th ed. Prentice Hall.

Marinkovic, V., and V. Obradovic. 2015. Customers’ emotional reactions in the banking industry. International Journal of Bank Marketing 33 (3): 243–260.

MarketsandMarkets. 2021. Loyalty management market by component. Research report, https://www.marketsandmarkets.com/Market-Reports/loyalty-management-market-172873907.html. Accessed 28 Mar 2022.

Martucci, B. 2022. 29 Best new bank account promotions & offers January 2022. Money Crashers, 18 January, https://www.moneycrashers.com/best-new-bank-account-promotion. Acessed 27 Jan 2022.

McCall, M., and C. Voorhees. 2010. The drivers of loyalty program success: An organizing framework and research agenda. Cornell Hospitality Quarterly 51 (1): 35–52.

McKinsey & Company. 2021. Disrupting the disruptors: Business building for Banks. April, https://www.mckinsey.com/industries/financial-services/our-insights/disrupting-the-disruptors-business-building-for-banks. Accessed 26 Mar 2022.

Meyer-Waarden, L. 2008. The influence of loyalty programme membership on customer purchase behaviour. European Journal of Marketing 42 (1/2): 87–114.

Meyer-Waarden, L. 2015. Effects of loyalty program rewards on store loyalty. Journal of Retailing and Consumer Services Elsevier 24 (2015): 22–32.

Milan, G.S., L.A. Slongo, L. Eberle, D. De Toni, and S. Bebber. 2018. Determinants of customer loyalty: a study with customers of a Brazilian bank. Benchmarking: an International Journal 25 (9): 3935–3950.

Mimouni-Chaabane, A., and P. Volle. 2010. Perceived benefits of loyalty programs: Scale development and implications for relational strategies. Journal of Business Research 63 (1): 32–37.

Mukerjee, K. 2018. The impact of brand experience, service quality and perceived value on word of mouth of retail bank customers: Investigating the mediating effect of loyalty. Journal of Financial Services Marketing 23 (1): 12–24.

Murthi, B.P.S., E.M. Steffes, and A.A. Rasheed. 2011. What price loyalty? A fresh look at loyalty programs in the credit card industry. Journal of Financial Services Marketing 16 (1): 5–13.

Murugiah, L., and H.A. Akgam. 2015. Study of customer satisfaction in the banking sector in Libya. Journal of Economics, Business and Management 3 (7): 674–677.