In 1971, India invaded Pakistan and used the ensuing military victory to create a new state out of a large chunk of Pakistani territory. India's actions were widely criticized. For example, speaking to the UN Security Council, US Ambassador to the UN George Bush described the invasion as “force in violation of the United Nations Charter.”Footnote 1 Speaking to the press on behalf of the US government, he called the invasion “aggression” against Pakistan.Footnote 2 A UN General Assembly resolution taking an anti-India position was passed overwhelmingly, 104 to 11.Footnote 3 India, and others including the USSR, counter-argued, claiming that India's use of force was a humanitarian intervention. Recognition of the proposed new state called Bangladesh was initially opposed and resisted, with reasons including that it would violate international law, that such recognition would “guarantee the fruits of aggression,”Footnote 4 and that the new state did not command enough loyalty. A request to invite representatives of Bangladesh to the Security Council was denied because a new state with the necessary criteria for recognition did not exist.Footnote 5 Two proposed Security Council resolutions rejecting the transfer of political authority to Bangladesh were defeated by a Soviet veto. Soviet-drafted resolutions including “recognition [of] the will of the East Pakistan population, as expressed, clearly and definitely, in … elections” were rejected.Footnote 6 Despite this initial widespread condemnation, several months after the Indian invasion, dozens of states recognized Bangladesh and accepted it as a new member of the international community. How did states reconcile this contradiction? Why did states that initially firmly rejected giving authority to a new state in East Pakistan turn around and recognize Bangladesh?

This puzzle is just one instance of international actors arguing over their actions and policies and those of their opponents. States often disagree about a policy that requires the consent or participation of the rest of the international community and so try to win over the undecided. As well as using bribery and coercive threats, states try to make the policy seem useful, good, or legitimate.Footnote 7 That is, they make normative arguments. Their goal is to make arguments that are as convincing as possible.Footnote 8 Of course, at the same time, the opposing group of states is attempting the same thing. Arguments are met with counter-arguments. But do such arguments have any influence on the overall outcome? Normative argumentation can be powerful but only if your version wins out over the opponents'. What makes one argument better than another?

States have a particular way of trying to win normative arguments. Rather than using the pure force of abstract moral reasoning, states try to move the locus of contestation to an arena where they can make practical progress—the evidence or the empirical facts in support of their argument. It is not given by nature what facts are relevant to normative arguments and so there are two things states can do that might allow them to manipulate an audience's attitude toward a policy. First, states can reach into the intersubjective collection of ideas, symbols, and rhetorical commonplacesFootnote 9 and link together some empirical fact and some part of their normative argument. In particular, they might be able to define the empirical fact such that it is the result of, or constituted by, an action that they can take. Second, they can take action to change the empirical situation so that it is congruent with their argument. Standard stories of manipulation include lying,Footnote 10 deception,Footnote 11 and costly signaling,Footnote 12 but these are not the only ways of understanding what states can do. In particular, if you can remove or dilute objections to a policy by changing the normative status of that policy, then people will be less likely to oppose and more likely to support your preferred policy. One important influence on the acceptability of a normative argument is the extent to which the facts conform to the premises (explicit or implicit) of the argument. A central problem in international politics is, then, how can you make your version of reality seem more real than your opponents' version?

I analyze how states try to bolster their position by first constructing an argument in which a particular action represents or manifests part of the argument, and then by performing that action to make the argument seem more convincing. This process I call rhetorical adduction.Footnote 13 The paper challenges IR theories of communication that deny a causal role to the content of normative arguments. It also diverges from a leading view in the literature on argumentation and rhetorical action on how arguments have their effects and instead builds an alternative framework that integrates strategic argumentation theory from IR with theory from psychology about how people make choices based on compelling reasons rather than cost-benefit analysis, as well as theory from sociology about how people resolve morally complex situations through the performance of “reality tests.”Footnote 14

Specifically, I investigate the peace-making process after the 1971 Indo-Pakistani war, or the Bangladesh Liberation War. I argue that the recognition of the new state of Bangladesh and the withdrawal of Indian troops from Bangladeshi territory were both driven by rhetorical adduction. States were not already inclined to recognize Bangladesh because of the intense political violence in East Pakistan and recognition decisions were not uncontested and regularized applications of international law. Further, India's withdrawal was not a result of high occupation costs (or the expectation thereof) or other Bangladeshi resistance. Instead, recognition was made possible by the argument that the withdrawal of Indian troops from Bangladesh meant that recognizing Bangladesh would not violate norms of non-aggression, self-determination, or the international legal norm of effective control of territory, and withdrawal was aimed at bolstering that argument.

How Do Arguments Have Their Effects?

The current literature on the role of argumentation can be divided into three categories according to the types of effects they understand arguments to have.Footnote 15 The leading two approaches are based on a model of action in which actors have a set of preferences (complete and transitive). Rationalist models do not allow for arguments to change preferences (although they might reveal information that would change beliefs).Footnote 16 Persuasionists allow for arguments to be causal, but believe that the only causally relevant effect arguments have is to change preferences. Finnemore and Sikkink define persuasion as the effective attempt by advocates to “change the utility functions of other players to reflect some new normative commitment.”Footnote 17 Once changed, preferences interact with beliefs to produce action different from what would have happened without the argument. An influential example of persuasionism is Risse's seminal account of the “logic of arguing,” a third alternative to strategic, utility-maximizing, action and rule-guided behavior.Footnote 18 This involved actors engaging in “truth seeking with the aim of reaching a mutual understanding based on a reasoned consensus.”Footnote 19 However, Risse's account has several limitations. First, it cannot easily deal with rhetorical action, or the strategic use of argumentation and discourse. Following Habermas, Risse sees action as either strategic, in that preferences are fully defined and fixed and completely immune to any talk, or as arguing, where actors are willing to change their previous preferences because of the logical power of an argument. The contrast is between doing something because a more powerful actor coerces you to, and because you newly believe that this is the right thing to do. However, as Schimmelfennig and Müller point out, this distinction is untenable because rhetorical action is both strategic and concerned with argumentation.Footnote 20 How can these be reconciled? One way that stays within Risse's framework is that rhetorical action can enlist both sincere agreement and also insincere acquiescence. Some actors who are under social pressure may not change their deeply held normative beliefs, or feel ashamed, but instead refrain from behavior intersubjectively constructed as illegitimate to the extent that they are concerned about their standing and reputation in the community. They might also want to leverage their reputation in later rhetorical contestation. The potential social fallout from rejecting what you think seems to other people a reasonable argument could have constraining or motivating effects.Footnote 21

For Risse, the crucial distinction between rhetorical and communicative action is whether the arguers are willing to change their minds or be persuaded.Footnote 22 This he defines in terms of changing “interests” or “views of the world”Footnote 23 as a result of the better argument where considerations of power and hierarchy are absent. However, the second limitation of a standard persuasionist account is that this ignores the numerous ways that people's attitudes can be influenced through irrational means. Risse himself uses several examples as instances of communicative action that undercut his definition. One is that actors with “authoritative knowledge or moral authority” will be more convincing to an audience than actors with known private interests.Footnote 24 If this is true, it is not because of a logical property of the better argument. The nonlogical element to the superior convincingness of an argument is an example of a whole class of influences on argumentation that is absent from Risse's schema. An alternative strand of the argumentation literature,Footnote 25 as well as the strategic framing literatureFootnote 26 allows for a variety of effects of discourse.

The third problem with a persuasionist account is the implicitly binary nature of the effect of argumentation. At time t 1, A prefers x over y. Then argumentation occurs. Finally, at time t 2, A prefers y over x. But this kind of attitude change is only one possible effect of argumentation. Various other possible effects have been identified. For example, Benford and Snow identify three framing tasks: diagnostic framing for the identification of a problem and assignment of blame, prognostic framing to suggest solutions to a problem or strategies to pursue, and motivational framing that provides a rationale or call to action.Footnote 27 A particular type of effect is that argumentation can change the normative status of an action. Actors vary in how much they care about normative statuses as well as any particular normative status. Normative status is not necessarily binary, such as good or bad. Instead, an act can vary from despicable through distasteful, to neutral, and then to admirable and heroic. It can also range from forbidden, through frowned upon and excused to permitted, and then to obligatory. Pushing in line has a different normative status from murder, though both are norm violations. Another important type of normative status is the difference between a clear violation and an excused exception, for example, murder and killing in self-defense. When an act appears to potentially represent a norm violation, actors attempt to justify it, both to themselves and to outside audiences. As Shannon explains, this difference often hinges on “one's ability to define a situation in a way that allows socially accepted violation.”Footnote 28

Fourth, persuasionism follows rationalism in assuming what Slovic calls “stable, well-articulated preferences,”Footnote 29 that is, clearly defined prior preferences over outcomes (i.e., completeness of preferences). Sometimes, people have preferences that are clear and do not change over time. In such cases, argumentation and framing will probably have relatively little effect. However, in other situations, people do not have complete preferences over outcomes. For example, they might have conflicting values, like the tradeoff between the cheapest, the most convenient, and the best-quality option, making an overall valuation impossible. Their preferences may also be different over time, even very short intervals. One set of findings from psychology is that preferences “are frequently constructed in the moment and are susceptible to fleeting situational factors.”Footnote 30 The extent to which preferences in general are stable and complete is an area of ongoing research, but in any particular situation, the less clearly formed and immutable preferences are, the more likely it is that argumentation has a causal effect on action.

Reason-based Choice

What is the nature of this causal effect if it is not changing actors' preferences from x > y to y > x? A prominent alternative to a value-based model of action (like expected utility theory or prospect theory) is reason-based choice.Footnote 31 A value-based model specifies how much an actor values the alternatives along a single dimension, like utility. This type of model explains a choice with reference to its having the highest value.Footnote 32 By contrast, a reason-based choice analysis identifies a variety of reasons for and against the various alternatives and explains a choice with reference to the balance of those reasons. People choose an alternative because they can provide “a compelling argument for choice that can be used to justify the decision to oneself as well as to others.”Footnote 33

Reason-based choice accords far more strongly with our intuitive ideas about how we reason and make choices. When we normally think and talk about making choices, we consider and present reasons that an option would be better as well as reasons that an option would be worse. This idea is prominent in the international law literature as well as being present in IR.Footnote 34 The fact that individuals can be conflicted in decision making is more consistent with conflicting reasons being hard to reconcile than it is with actors having clear ideas about their ordering of the options.

Many empirically established violations of features of rationality can be easily accommodated in a reason-based framework. One such feature is procedure invariance, or the idea that preferences over options are independent of the method used to elicit them. Shafir and colleages point out that notable features provide compelling reasons for the decision: “reasons for choosing are more compelling when we choose than when we reject, and reasons for rejecting matter more when we reject than when we choose.”Footnote 35

Other violations of rationality that can be accommodated in a reason-based choice framework are the sunk-cost fallacy, preference inversion, framing effects, loss aversion, the endowment effect, status-quo bias, attribute balance, feature creep, and the disjunction effect, among others.Footnote 36 The importance of reasons for decision making is increased when the decision maker has to justify a decision to others.Footnote 37 Such situations are rife in international politics. The inability of standard rational choice theory to account for the role of reasons in decision making has prompted attempts at formalizing preference formation and change in terms of the basket of reasons that are motivationally salient.Footnote 38

A reason-based choice model of action can provide a way for rhetorical argumentation to be causally relevant with respect to choice of action. If actors do not have complete, stable preferences over the options presented, an argument can “highlight different aspects of the options and bring forth different reasons and considerations that influence decision.”Footnote 39 In choice situations where either preferences are nonexistent or inchoate, or no option dominates (i.e., each option is highest on at least one attribute), an argument could provide a hitherto nonsalient reason for or against an option.

This shows that it is not necessary for anyone to change their mind for rhetorical arguments to have a causal effect on action. Actors can engage in strategic rhetorical action while also being involuntarily susceptible to the sometimes-subconscious effects of argumentation. One type of effect can be to change the normative status of an action or situation.

Rhetorical action matters more when there is a third-party audience who is undecided or whose conception of a situation's meaning is not fixed, or whose support is up for grabs in some way. Krebs and Jackson have elaborated a general model of rhetorical action that incorporates the role of this audience.Footnote 40 In this model, two actors are arguing over a policy and a third actor, the audience, is crucial to the success of this policy. The two arguers (the claimant and the opposition) engage in rhetorical contestation to win over the audience. Whichever actor is more successful in this rhetorical contestation is rewarded with more or less support or resistance for the policy in question. Rhetorical coercion occurs when one actor is forced to stop arguing against or even to advocate for a policy. Rhetorical coercion is possible because actors need to justify their behavior to each other and because these justifications are constrained (e.g., by the limits of intersubjectively shared discourse).

Say there is a policy p that has a set of reasons in favor and also a set of reasons against or objections o 1, o 2, …, o n , such that the audience does not have a clear stable preference over whether the policy is enacted or not. If the audience finds a potential objection o i compelling in some way, the audience resists the action.Footnote 41 Argumentation can be used to remove an objection by altering the normative status of the policy. A common way to remove an objection is by changing the normative status from a clear violation of a norm to an excused exception to the norm. The argument is then causally relevant to the action in the case that the action would not have occurred in the face of resistance by the audience, ceteris paribus. Here, removing an objection does not mean that policies of the same type as p are forever believed to be morally right by everyone. All that it means is that resistance to policy p is reduced or eliminated in this particular case. This conception of the effect of argumentation allows that an argument can be successful at removing an objection and yet have no impact on behavior because the balance of reasons is still heavily one sided. The recognition of Bangladesh is an especially good case to observe the effect of argumentation on behavior because the reasons for and against were relatively evenly balanced.

As Kornprobst notes, there can be different levels of support for, or a lack of resistance to, a policy. He identifies acquiescence, compromise, and consensus.Footnote 42 Acquiescence is the weakest; people simply acquiesce with a dominant argument but they are not convinced. Compromise involves people who are not convinced but actively agree to mutual concessions as long as they do not violate their deepest-held beliefs. Consensus, the strongest, is when actors both publicly agree with and internally believe in the policy. These are differing levels of support for a policy. Resistance to a policy similarly varies. People could simply refuse to support the policy, effectively doing nothing. They could grudgingly adopt the policy while still challenging its justification. They might both reject the policy and argue against it. At the extreme, they could reject the policy and actively take steps to try and reverse it. When a policy's success is dependent upon the attitudes and actions of an audience group of states, altering the level of support or resistance to that policy is an important goal of both the claimant and opposition groups.Footnote 43

What Makes For a Better Argument?

If argumentation can have these effects, what is it that determines which arguments are successful and which fail? For Krebs and Jackson, as in many accounts of rhetorical action (and framing and securitization),Footnote 44 the public's or audience's acceptance or rejection of the framing or implications of a claimant's arguments are central. The audience serves as the adjudicator of the better argument.Footnote 45 Krebs and Jackson largely bracket the question of why a public finds an argument acceptable. But it seems reasonable that there are multiple influences on a public's acceptance or rejection of an argument. One of these influences, they posit, is the limits on creating or formulating the basic building blocks of argumentation—rhetorical commonplaces; “they are not free to deploy utterly alien formulations in the course of contestation; such arguments would fall … on deaf ears.”Footnote 46 This is not the only conceivable limitation. Some writers have looked to features of the normative ideas themselves,Footnote 47 or to a comparison with some sort of ideal to try and explain why audiences find some arguments more acceptable than others. For example, Elster posits that the appearance of impartiality and consistency is a crucial factor, going so far as to appeal to a “civilizing force of hypocrisy.”Footnote 48

A seemingly obvious factor is the role of evidence. My argument relies upon the idea that empirical evidence supporting an argument makes that argument more convincing. This seems uncontroversialFootnote 49 and is the foundation of the rationalist literature on communication. For rationalists, effective communication takes the form of costly signalingFootnote 50 or cheap talkFootnote 51 and is evaluated on those terms. However, even though these are important and useful ideas, they are at best incomplete. Even costly signals require interpretation. For example, whether a costly signal can change beliefs requires that “there is objective and uncontestable knowledge, shared among sender and receiver, about what costs mean to either.”Footnote 52 Jervis makes the point that “actions are not automatically less ambiguous than words. Indeed, without an accompanying message, it may be impossible for the perceiving actor to determine what image the other is trying to project.”Footnote 53

With many political phenomena, communication is complicated by the ubiquity of essentially contested concepts. An issue with some existing work is the stark distinction usually drawn between “signaling facts” and “entering a moral discourse.”Footnote 54 While it is reasonable to draw this distinction in the abstract, people in practice often experience moral discourse as an indistinguishable part of empirical discourse. In particular, people often see moral judgments as resting definitively on empirical facts. However, despite their importance to decision making, it is not clear what the empirical referent of concepts like democracy, corruption, genocide, terrorism, or aggression are.Footnote 55 Further, social norms, rules, and institutions have an “open texture” in the sense that they refer to classes of persons and classes of acts, things, and circumstances and as such it is uncertain whether and how they apply “in particular concrete cases.”Footnote 56 To come to a judgment on whether an action or actor has a property, like that of being democratic, or being genocide, or being the product of self-determination, people use shorthand indicators. As Hanrieder points out,Footnote 57 morally complex situations are resolved through the performance of “critical tests” which rely on some performance, including actions or reference to symbols.

Boltanski and Thevenot note that normative reasoning does not often take the ideal form represented in philosophy journals in which reasoning over the empirical situation and the normative situation are kept strictly separate. Instead, in practice people resolve contests over normative concepts (like the legitimacy of an action or whether an act or a situation is an instance of a norm) by pointing to particular empirical facts as determinative of normative conclusions. In conditions of ambiguity and uncertainty, such as a contestation over legitimacy, people rely on “reality tests”Footnote 58 in which judgments about the fluid and plastic social world rest on “the factual nature of the elements that have been invoked.”Footnote 59 For example, when reacting to a police officer's killing of a suspect, people might rest their moral judgment solely on whether the suspect was armed or unarmed, or who shot first, despite this only being one small part of the possible complex normative argumentation we could build around this question.

Similarly, Mor mentions how important the “provision of some new facts (selected and presented with a certain interpretation in mind)” is for the process of legitimation and counter-legitimation that affects external support for an actor's position.Footnote 60 In the framing literature, “empirical credibility”Footnote 61 is a constraint on framing events. The issue is not whether “claims are factual or valid, but whether their empirical referents lend themselves to being perceived as ‘real’ indicators of the diagnostic claims.”Footnote 62

So, a normative argument can be better if it makes a normative label more convincing through referring to some fact about the situation. But what facts are relevant or influential? Actors are not able to say anything they like and have an audience accept their formulation. If there are rules governing the type of situation, those rules specify relevant facts. But even when rules are precise and comprehensive, there is inevitably a judgment made on whether a particular case counts as an instance of the general categories referred to in the rules. Those judgments are made with reference to an intersubjectively defined collection of characteristics. What matters is not the truth of the matter but the socially defined markers of what counts. This idea is related to the concept of a “practice” or a competent performance of a socially recognized pattern of behavior,Footnote 63 and is linked to the theme in the argumentation literature that arguments have to be anchored in something that is widely taken for granted, or rhetorical commonplaces, for them to make sense and be convincing.Footnote 64 One example comes from the procedure for obtaining US resident alien status via spousal application (a “green card”). A vital element is whether the relationship between the petitioner and spouse conforms to the practice of a “bona fide marriage” according to the United States Citizenship and Immigration Services, including whether there are any “discrepancies in statements on questions for which a husband and wife should have common knowledge.”Footnote 65 A competent performance of a “bona fide marriage” here relies upon conforming to a set of socially defined or intersubjective characteristics.

To summarize, unlike rationalist or persuasionist claims, arguments can have effects by providing reasons for or against a policy, especially when the support of a third-party audience is up for grabs. These effects include changing the normative status of an action, such as from a norm violation to an excused exception. Normative arguments can be made more convincing when they are anchored in empirical evidence, such as the actions of the parties, but this evidence is effective only when it is rhetorically linked to the argument. If an action conforms to some intersubjectively defined criteria, that is, is a competent performance, it is more likely to be accepted. These ideas together suggest a mechanism whereby actors can use actions to bolster normative arguments. I call this mechanism “rhetorical adduction.”

Rhetorical Adduction

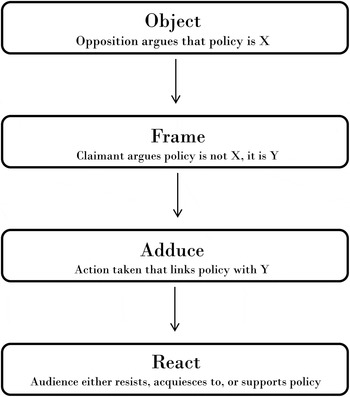

Rhetorical adduction is the process by which states try to raise support for their position first by constructing an argument in which a particular action represents part of an argument, and then by performing that action to make the argument seem more convincing. Here I lay out a schematic account of the process. See Figure 1 for a representation of the process.

Figure 1. The Process of Rhetorical Adduction

Two groups of states have a dispute over a policy whose success depends in some way on the actions of a third group of states uncommitted or undecided about the policy. For simplicity, the policy could take one of two values; it could either be enacted or not. The group of states that wants the policy enacted is denoted C, the claimant. The group of states that does not want the policy enacted is denoted O, the opposition. The undecided group of states is denoted P, the public or audience, which can either resist or support the policy (or at least acquiesce in its enactment). O makes an argument. This argument raises an objection to the policy that involves a claim that the policy is illegitimate because it has property X. C then makes a counterargument, in which C claims that the policy does not have property X and that instead the policy has property Y, which means that it is not illegitimate. Further, the counter-argument specifies some action, A, that demonstrates that the policy has property Y. C then performs action A. P then supports the policy.

What does rhetorical adduction consist of in this process? First, it involves the counter-argument that the policy has a property that means it is legitimate, including the claim that a particular action means the policy has that property (the rhetorical part). The second part of rhetorical adduction is actually performing that action as “proof” that the policy has the property (the “adduction” part).

At several points in this process, it may get derailed. O may not, or may not be able to, make an argument. C may not, or may not be able to, concoct a counter-argument that makes sense. C may then not be able to perform the action. Even if it is performed, it may not be convincing to the audience, which may then decide not to support the policy.

An ideal type of the underlying structure of the argumentation involved in rhetorical adduction is the following:Footnote 66

-

1) Policy p has property X.

-

2) If a policy has property X, it is illegitimate.

-

2*) Thus, p is illegitimate.

The argument being made by O, the opposition to the policy at stake, is that because policy p has property X, it is illegitimate (1, 2, → 2*).

-

3) A policy cannot have both property X and property Y.

-

4) Policy p has property Y.

-

5) Thus, policy p does not have property X.

-

5*) Thus, policy p does not have property Y.

-

6) Thus, 2* is false.

The counter-argument being made by the claimant C is that the policy has property Y and that, because a policy cannot have both X and Y, the policy does not have X and thus is not illegitimate (3, 4, → 5, → 6). Crucially, the audience has to resolve the contradiction between 1, 3, and 4 in favor of conclusion 5 rather than 5*. Part of rhetorical adduction is making it so that 4 is more plausible than 1 (7, 8, → 4).

-

7) If Z, then policy p has property Y

-

8) Z.

Here Z is some fact with an empirical referent, such as an action. For intuitiveness, an everyday example might be a situation in which a faction in a university department wants to hire an inside candidate, but they are opposed by another department faction, on the basis that this would be illegitimate. Possible arguments might be that this would be nepotism, or that the person might not be the best candidate. The first faction then argues that if they run a standard search, the result of that search would not be nepotism and would be the best of available candidates, and hence be legitimate. The department runs the search, and then selects the inside candidate. The central administration then acquiesces to this decision.

Applying the Model: Indian Intervention in Pakistan and the Recognition of Bangladesh

To demonstrate how the rhetorical adduction model explains behavior, I apply the model to the peace-making process at the end of the Indo-Pakistani war of 1971. In particular, the model can explain both why India withdrew its troops from East Pakistan/Bangladesh so quickly after defeating West Pakistani forces, and why states that initially opposed India's actions and the creation of a new state ended up recognizing Bangladesh.

The recognition of the new state of Bangladesh was made possible by rhetorical adduction. That is, an argument was made that the proposed withdrawal of Indian troops from Bangladesh meant that recognizing Bangladesh would not violate norms of non-aggression, self-determination, or the international legal norm of effective control of territory. Indian troops were withdrawn from Bangladesh to bolster these arguments. Some states recognized Bangladesh because the Indian agreement to withdraw and then actual withdrawal of troops removed their objections to recognition. By contrast, states were not predisposed to recognize Bangladesh because of the mass killing of Bengalis, nor were they simply applying the international law of sovereignty to the situation. India did not withdraw troops because they experienced or anticipated high occupation costs.

Historical Context

Three themes in the historical context were relevant to the arguments over recognition.Footnote 67 First, was the putative Bangladeshi state a result of self-determination? Second, what was the attitude of the international community to India's use of force? And third, what was the attitude of decision makers in other states toward a potential new state of Bangladesh?

The feature most relevant to the question of self-determination for Bangladesh was the democratic election held in Pakistan in December 1970, its first since independence from Britain and partition from India in 1947. Sheikh Mujibur Rahman's Bengali nationalist party, the Awami League, won an overall majority of seats in the parliament (including both East and West Pakistan). However, the league was prevented from forming a Pakistani government by Zulfikar Ali Bhutto, leader of the Pakistan People's Party, which had won a majority of the seats from West Pakistan, and the previous leader, President General Yahya Khan. Starting in March 1971, a violent crackdown on Bengali political opposition by West Pakistani armed forces left hundreds of thousands deadFootnote 68 and included the incarceration of Sheikh Mujib. This resulted in a massive outpouring of refugees across the border into Indian Bengal. In April, the Awami League issued a declaration of independence that was initially ignored internationally.

India's intervention into East Pakistan was widely criticized. Soon after the violence began, the number of refugees fleeing to India was estimated to be in the millions and Prime Minister Indira Gandhi decided on a military intervention into East Pakistan.Footnote 69 In October, the Indian army began launching attacks and holding territory inside East Pakistan.Footnote 70 India declared war on Pakistan on 3 December, citing self-defense against Pakistani air attacks. However, India was widely treated as the initiator of cross-border violence. Bhutto, the new president of West Pakistan, argued that a USSR-proposed Security Council resolution transferring sovereignty to Bangladesh meant legitimizing aggression:

This is gunboat diplomacy in its worst form. It makes the Hitlerite aggression pale into insignificance, because Hitlerite aggression was not accepted by the world.Footnote 71

Impose any decision, have a treaty worse than the Treaty of Versailles, legalize aggression, legalize occupation, legalize everything that has been illegal up to 15 December 1971. I will not be a party to it.Footnote 72

Similar sentiments were expressed by some other states and the resolution was not adopted. Other UNSC resolutions that merely called for a ceasefire and a withdrawal to internationally recognized borders but that pointedly excluded the transferal of political authority to the Awami League and Bangladesh were vetoed by the USSR. This stalemate in the Security Council led to the transfer of the issue to the General Assembly and subsequently the near-unanimous (104 to 11 with ten abstentions) General Assembly resolution 2793, which duplicated the resolutions vetoed by the USSR. Indian military success continued as the USSR vetoed another UNSC resolution on 13 December and the next day, Pakistani forces in East Pakistan proposed a ceasefire, which India accepted. However, after the end of hostilities, India's victory was not immediately accepted and normalized by those states who had been so vociferously denouncing the invasion only days before. As Henry Kissinger said to US President Richard Nixon, “the Indians are demanding the UN agree for the turnover of authority to the Bangla Desh. Now that would make the UN an active participant in aggression. I don't think we can agree to this.”Footnote 73

Before and during the war between India and Pakistan, no states had a clear preference for the existence of a new Bangla Desh state (apart from the belligerents). Based on Indian governmental and personal papers, Bass recounts the efforts of Gandhi, P.N. Haksar, principal secretary to the president, and Indian diplomats in a global appeal for help. Initially appealing to sixty-one countries, the Indians tried to publicize what they called the genocide against the Bengalis. External Affairs Minister Swaran Singh personally visited numerous foreign capitals in June 1971, Education Minister Siddhartha Shankar Ray toured Asia, and Home Affairs Minister K.C. Pant traveled around Latin America, all asking for help with the refugee problem and specifically asking for recognition of Bangla Desh. No states agreed to recognize, and only a few made public statements of sympathy or support. Bass describes the whole enterprise as “crushingly disappointing.”Footnote 74 Even the Soviet Union, publicly supportive of both India and Bangladesh throughout the crisis, resisted. Alexei Kosygin, Soviet premier, privately urged D.P. Dhar, Indian Ambassador to Moscow, to avoid war with Pakistan, and subsequently told Singh not to recognize Bangladesh.Footnote 75 What this indicates is that most states were against recognition before the war, or at the very least were unclear about whether they wanted to recognize Bangladesh. In a memorable episode, Mexico's president had so little idea about the situation that he refused to believe that West and East Pakistan were so far apart until an atlas was fetched, at which point he said, “By God, it's really so.”Footnote 76

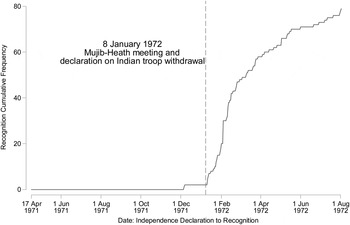

Apart from India and Bhutan, no states recognized Bangladesh before 11 January 1972, even after the end of hostilities on 14 December. Between 11 January and 14 February 1972, thirty-six states recognized Bangladesh, including the UK and nine others on 4 February (see Figure 2). The US did not recognize Bangladesh until 4 April. Bangladesh applied for UN membership later that year, but a UNSC resolution admitting the new state was vetoed by China in August. Bangladesh was not admitted to the UN until 1974.

Figure 2. Timing and Recognition of Bangladesh

The Role of Troop Withdrawal

After Sheikh Mujib was released from captivity in West Pakistan, he traveled to London where, in a meeting on 8 January 1972, the British government impressed upon him the importance of Indian troop withdrawal for the recognition of Bangladesh.Footnote 77 However, the connection between these two things was not immediately apparent. For example, UK Ambassador to Turkey Roderick Sarell reported that the senior members of the Turkish foreign policy establishment had agreed to not recognize Bangladesh only after the Indian troop presence in Bangladesh was presented to them as an issue and a barrier to recognition.Footnote 78 Similarly, the Sri Lankan (Ceylonese) government asked “whether Mujib has stated publicly that Mrs Gandhi has agreed to withdraw Indian forces on his request,” but only after having it explained to them that withdrawal was relevant to recognition.Footnote 79 Mujib and members of the Indian government insisted that Indian troops were in Bangladesh only at the request of the Bangladeshi administration and Gandhi and Mujib jointly declared on 8 February 1972 that India would withdraw all its troops from Bangladesh by 25 March.Footnote 80 Mujib in fact declared that all troops were withdrawn on 13 March.Footnote 81

There were three arguments to which Indian troop withdrawal was crucially linked. First, withdrawal meant that the Indian military intervention did not count as aggression, or was an excused exception to the general rule, so recognizing the fruits of that intervention did not count as legitimizing aggression. This might sound counterintuitive; an aggression is not undone if the perpetrator withdraws afterwards.Footnote 82 However, the case was made that a key characteristic of aggression or a war of conquest was the desire to annex or occupy territory, and withdrawal indicated that India had no desire to do so. So the invasion was in effect recast as an excused exception to the rule against the use of force. Analogously, whether taking an object counts as theft or borrowing depends on whether it is given back. Second, withdrawal was also claimed to mean that the creation of the state of Bangladesh was an act of self-determination. Third, and finally, the conventional international legal criteria for recognition included effective control of territory and so recognition was not impeded by being illegal. There was no question that Indian troops had crossed the border into East Pakistan. The issue to be resolved was whether this counted as aggression, or whether the presence of Indian troops meant that the nascent Bangladesh government did not enjoy popular support.

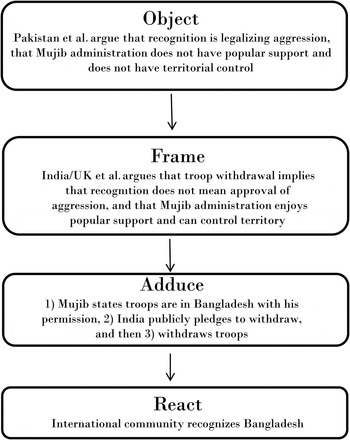

In terms of the rhetorical adduction model (see Figure 3), the policy at stake is the recognition of Bangladesh. The claimant is the Mujib administration, India, and other states like the UK who want Bangladesh to be recognized. The opposition includes Bhutto and the West Pakistan leadership, as well as China. The opposition charges that recognition is illegitimate because it has the following properties: (a) it would mean approving of aggression; (b) the Mujib government does not enjoy popular support; and (c) the Mujib government does not and cannot control the territory of East Pakistan. The claimant counter-argument is that if India withdraws its troops, then recognition will no longer imply approval of aggression and the Mujib government can be said to both enjoy popular support and control its territory.

Figure 3. Rhetorical Adduction and Recognizing Bangladesh

Note that I do not provide a complete account of the decisions to recognize Bangladesh, which were multifaceted.Footnote 83 The relevant claim here is that there were potential objections or sources of resistance to the recognition policy that were removed by rhetorical adduction. In the Bangladesh case, the sole remaining objections were removed and so rhetorical adduction made the difference between policy adoption and non-adoption. Two counterfactual scenarios are the following:

Counterfactual: What if the UK, India, and others had not argued that withdrawal excused the Indian invasion and legitimated the Bangladesh state?

If the UK and others had not fixed upon Indian withdrawal of troops as an indicator of the legitimacy of the use of force by India, and of the Mujib regime, then there would have been no reason for India to withdraw troops. Prior discussions between India and Bangladesh involved an Indian military presence.

Counterfactual: What if India had not withdrawn troops?

In a counterfactual world where India did not withdraw troops, resistance to the recognition policy would have been higher and some states would not have recognized Bangladesh.

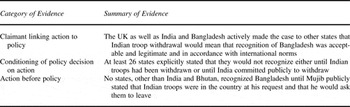

Observable Implications

The policy of recognizing Bangladesh was made possible by a combination of creative argumentation and the action of withdrawing Indian troops. So recognition happened (at least for some states) because of the argumentation and withdrawal. Also, withdrawal happened because of India's and Bangladesh's desire to legitimate recognition. What are the observable implications of these claims, given the theory I outlined? First, we should see explicit linking of the action (i.e., withdrawal) with the policy (i.e., recognition). Actors might say something like, “We have to do this (the action) so that the others can/will do that (the policy),” or “We have done this (the action), so now you can/must do that (the policy).” Second, we should see the recognition decision happen after the action that was adduced. Third, we should see explicit conditioning of the recognition decision on the action.

Claimant Linking Action to Policy

After Mujib's meeting with Heath in London on 8 January, members of the UK government accepted that Indian troops were in Bangladesh with the agreement of the Bangladeshi government, and that they would be withdrawn. From this meeting onward the British, the Indians, and the Mujib administration argued that the prospective withdrawal of Indian troops meant that recognition of Bangladesh was now an acceptable policy.

By 18 January 1972, British diplomats were arguing to other governments that recognition could go ahead because “it seemed to us that the normal criteria for recognition were just about fulfilled and we did not regard the presence of Indian troops, particularly given what had been said in public by Sheikh Mujib about their status and their eventual withdrawal, as a serious obstacle.”Footnote 84 In personal messages to state leaders, Heath argued that:

whatever view is taken of the manner of its creation, a new national entity is coming into being whose Government appears to command the general acceptance of the majority of the people. The maintenance of law and order is still, in the last resort, dependent upon the Indian Army, but their presence is accepted by the Government in Dacca and Mujib told me that, on his return, he would formally request the Army's withdrawal in accordance with a phased and agreed plan.Footnote 85

The reference to the manner of Bangladesh's creation can only refer to the illegitimacy of India's use of force. In parliament sessions, at Foreign Ministry press conferences, and during the prime minister's question time throughout January and February, the standard answers provided to questions about the presence of Indian troops, or the status of Bangladesh, were that Indian troops were in Bangladesh “by the will”Footnote 86 of the government, or “at the request”Footnote 87 of Mujib.

Table 1. Observable Implications

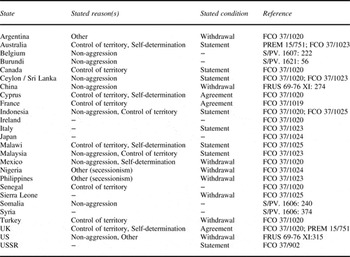

Conditioning of Policy Decision on Action

Prior to the Mujib-Heath meeting on 8 January 1972, only two states, India and Bhutan, had recognized the state of Bangladesh, and no states had done so since the end of the fighting and the ceasefire declaration on 17 December 1971.Footnote 88 There were four categories of reasons given to British officials for why recognition of Bangladesh might be a problem.Footnote 89 One was that recognition might negatively affect the state's relations with Pakistan, and for some states, like Portugal and Hungary, this was their only stated concern. However, many states conditioned their recognition decision on an action related to Indian troop withdrawal and gave three different types of reasons for doing so. States also differed in the extent of troop withdrawal they required before recognition. See Table 2 for a full list of states, their stated reason for conditioning recognition on withdrawal (if any can be identified), and what recognition was conditioned on (whether actual withdrawal or a proxy).

Table 2. Conditioning Recognition on Indian Troop Withdrawal

Notes: FCO: UK Foreign and Commonwealth Offices Archives; S/PV: United Nations Security Council Official Record; PREM: UK Premiers Archives; FRUS: Foreign Relations of the United States series.

The first type of reason, opposition to condoning or legitimizing aggression, is labeled as “Non-aggression.” A good example comes from Mexican Foreign Minister Emilio Óscar Rabasa who reported that the Mexican president had decided not to recognize Bangladesh because, “since the Mexicans, like many Latin Americans, refuse to condone territorial aggrandizement as a result of war, they would prefer to wait on the withdrawal of Indian troops as the sign of true independence.”Footnote 90

This statement also appeals to “true independence.” Self-determination is another important value expressed by the Mexican representative and is the second type of reason commonly appealed to as justifying recognition as Bangladesh. For example, Australia's justification of its decision to recognize Bangladesh includes that “there was no doubt of the breadth and depth of the support which Sheikh Mujib's Government enjoyed among the people of Bangla Desh.”Footnote 91

The third type of reason was whether the Mujib administration had control of the territory. This was part of the often-cited international legal criteria and played a central part in several states' reasoning. For example, Mitchell Sharp, Canadian Minister of Foreign Affairs, worried about “the question that is concerning everyone, namely, is the govt that has been formed in Bangladesh really in authority and what is the effect of the presence of Indian troops.”Footnote 92

States also varied in what exactly they were conditioning their decision on. Many recognition decisions came after actions that were effectively proxies for the withdrawal of Indian troops. While some states required actual verified withdrawal, others were willing to accept reassurances from the Bangladesh and Indian governments. For the UK, Mujib's assurance that Indian troops were in Bangladesh “at his behest and [that] the Indian Government has undertaken to withdraw them at his request,” was enough.Footnote 93 Ever since Mujib's meeting with UK Prime Minister Heath on 8 January, in which Mujib pledged to request the withdrawal of Indian troops as soon as possible, the UK government had been explicitly linking Mujib's pledge with the recognition of Bangladesh. Previously, UK representatives had focused on the actual presence of Indian troops as a barrier to UK recognition when communicating with other governments, such as GermanyFootnote 94 and Vietnam.Footnote 95 This was despite the fact that UK Foreign Minister Alec Douglas-Home had said, “the British interest lies in recognising Bangla Desh sooner rather than later. Once we have recognised, we shall be in a better position to seek to influence the general policies of the new government and to protect British interests in the area.”Footnote 96 His reasoning was that it was “wrong to recognise for so long as the supreme authority in the territory of Bangla Desh is in practice exercised by the Indian Army commanders.”Footnote 97 Once it was clear that “the Indian Army had begun to leave; and those elements which remained did so at the request of [Mujib],” Douglas-Home informed the cabinet that the UK would recognize.Footnote 98 India also repeatedly and publicly stated that its army would leave at the request of Mujib.Footnote 99

Countries like the UK who stated that they were conditioning recognition on Mujib's agreeing that Indian troops were in the country with Mujib's permission are marked “Agreement” in Table 2. States conditioning their decision on a formal announcement by India and Bangladesh that Indian troops would be withdrawn (with an official timetable) are marked “Statement.” One example was Italy, whose minimal requirement was that there should be some public commitment to withdrawal. Lo Prinzi (the chief of the Asian Desk in the Ministry of Foreign Affairs), initially said that “it would be helpful if, in the meantime, Mujib could announce a timetable for withdrawal.”Footnote 100 Later he explicitly conditioned recognition on withdrawal: “Lo Prinzi said the Foreign Ministry were now thinking of recommending that an appeal be made to Mujib to announce at least a timetable for withdrawal. If Mujib did this the Italians would have no difficulty in recognising earlier.”Footnote 101 By 3 February, the Italians had decided to “put off” recognition without “some withdrawal or engagement to withdraw Indian troops.”Footnote 102 In the end, the Italians, along with the French, did not formally recognize Bangladesh until 12 February 1972, a few days after the joint Indian–Bangladeshi troop withdrawal declaration on 8 February. Similarly, the Secretary-General of the Malaysian Ministry of Foreign Affairs said that it was “difficult for countries like Malaysia in absence of any move by Mujibur to make even a token reduction in the large Indian forces in Bangla Desh, or any positive statement about their withdrawal by the Indian Government.”Footnote 103 Canadian Prime Minister Pierre Trudeau asked Heath about withdrawal:

I wonder what the outcome has been of Mujib's intention, as described to you, that on his return to Dacca he would formally request the Indian Army's withdrawal in accordance with a phased and agreed plan. I recall a joint statement of January 9, the day before he returned, that the Indian forces would be withdrawn at the request of the Government of Bangla Desh but there was no timetable mentioned. If we and other countries could obtain firm information about such a plan, it would no doubt assist us in our evaluation of the situation.Footnote 104

Canada did not recognize Bangladesh until 14 February, after the 8 February joint Indian–Bangladesh declaration on troop withdrawal.

Finally, some states required confirmation of the full withdrawal of Indian troops before recognizing. These are marked “Withdrawal.” The sentiment was concisely stated by a senior Nigerian diplomat who explained that even though Indian assurances of withdrawal were assuring, they were not as assuring as withdrawal itself.Footnote 105

The US's decision-making process was complicated by Nixon's secretly organized visit to China in early 1972. The State Department had recommended that the US “position on recognition will depend inter alia on a commitment on withdrawal of Indian forces and the ability of the Bangla Desh government to assume the responsibilities and obligations of a sovereign and independent state.”Footnote 106 Henry Kissinger also included as a reason for delaying recognition of Bangladesh that “we did not want to move too quickly in blessing the fruits of India's action … In any case, Indian troops are scheduled to be withdrawn by March 25.”Footnote 107 Subsequently, at the explicit behest of the Chinese,Footnote 108 Nixon and Kissinger delayed recognition until 4 April, after Nixon had returned from China.

Timing of Action and Policy

For rhetorical adduction to be causally relevant to the policy at stake, the decision to support or adopt the policy should occur after the claimant has taken the action that legitimates the policy. As noted, states had three different types of action that they held to be a requirement for recognition. While not all states recognized Bangladesh after actual withdrawal had occurred, recognition decisions did follow the performance of the stated condition. For example, UK recognition followed Mujib's insistence that Indian troops were there with his agreement, Italian and Canadian recognition came after the joint declaration of a timetable for withdrawing troops, and Nigerian recognition followed the declaration of actual withdrawal.

Alternative Explanations

What are the alternative explanations for why there was initially such opposition to recognizing Bangladesh combined with subsequent widespread recognition? One alternative explanation is that states were inclined to recognize Bangladeshi independence as a result of the nature of the postelection pre-war violence in East Pakistan. However, the evidence runs counter to this possibility. The massacres by the West Pakistani forces (the case was made by the Indian parliament that this “amounts to genocide”),Footnote 109 were known about, being widely reported in the mainstream press like the New York Times and The Sunday Times.Footnote 110 However, this violence was simply not mentioned as a convincing reason for India's intervention. In fact, despite being well aware of their existence, no UN organ, like the Security Council or even the Sub-Commission on Prevention of Discrimination and Protection of Minorities or the Committee on Racial Discrimination, deliberately considered the massacres.Footnote 111 Wheeler analyzes the rhetoric used during the war to justify and judge Indian intervention in the context of the massacres in East Pakistan being a “supreme humanitarian emergency.”Footnote 112 He finds that despite recourse by India to humanitarian claims to classify its use of force as an exception to the rules, the society of states “emphatically rejected [those claims] as a legitimate basis for the use of force.”Footnote 113 Instead, “the Indian action was widely viewed as a breach of the rules that jeopardized the pillars of interstate order.”Footnote 114 Bass's account of the telegram notifying the US government of the violence by the diplomat Archer Blood supports the claim that few held the violence a good reason for Indian intervention. Despite India's diplomatic efforts to rally support by citing the violence and the burden on India of the millions of refugees, other countries replied “with firm exhortations to avoid military confrontation with Pakistan.”Footnote 115 Bass also argues that General Assembly resolution 2793 constituted a “worldwide repudiation of India's case for liberating Bangladesh.”Footnote 116 Debnath's focused evaluation of the UK finds that despite some domestic pressure, the British government actively rejected a classification of the violence as genocide and she concludes that reports of atrocities played no role in decision making.Footnote 117

Another alternative proposition is that there was an established set of rules, international law, that meant that there was no real need for contestation or argumentation (or rhetorical adduction), and the recognition of Bangladesh was merely a quasi-bureaucratic, rubber-stamp process of assessing whether the situation fit the criteria. Musson makes a related claim that “the British decision to recognize Bangladesh in early 1972 rested almost entirely on the fulfillment of international criteria.”Footnote 118 However, this possibility assumes a much deeper institutionalization of the norms governing secession and aggression than was the case. By contrast, the existing international law on the issues of recognition, secession, and the use of force were not conducive to allowing Bangladesh to become a state. According to Crawford, the general law is clear: unlawful use of force cannot create sovereignty—cannot make secession legal.Footnote 119 Shaw notes that Bangladesh is the only exception to the empirical rule that noncolonial secessions contrary to the consent of the mother state do not exist.Footnote 120 Effective control was at the time, and still is, a key principle in international law relevant to recognition of states and governments. However, after World War II, there was a substantial shift in recognizing practice away from effective control and toward normative principles as legitimate reasons for recognition, primarily anticolonialism and self-determination.Footnote 121 As Coggins finds, recognition of secessionist entities does not in fact follow a narrow interpretation of the international law principle of effective control and instead seems to vary according to the preferences of great powers, including legitimizing the violation of the norm of territorial integrity.Footnote 122

The other action explained as being driven by rhetorical adduction is the adduced action, the withdrawal of troops. One alternative argument is that prompt withdrawal was a result of India facing the prospect of high occupation costs early on. This is not plausible because the inhabitants of East Pakistan were not resisting the Indian forces and frequently welcomed Indian troops as saving them from the violence directed against them by the West Pakistani military.Footnote 123

Another alternative explanation is that Mujib wanted the troops to leave so that he would be less subject to pressure from the Indian government. In fact, the Mujib administration originally requested an Indian military presence, and invited Indian troops back into the country soon after withdrawal to assist the fledgling regime. Prior to Mujib's 8 January meeting with Heath, the Bangladeshi government position was that Indian army troops were essential to their plans. During a 6 January 1972 meeting between Indian government leaders, including Indira Gandhi and the Indian Defense Minister, Jagjivan Ram, and the Bangladeshi Foreign Minister Abdus Samad Azad, there was discussion of security issues. Ram “conveyed India's desire to recall Indian forces from Bangla Desh as soon as possible.”Footnote 124 Samad Azad resisted, emphasizing that “certain essential tasks still remain to be performed [by the] Indian Army.”Footnote 125 He then requested and was granted “full assistance in training of officers and men of Bangla Desh forces.”Footnote 126

The alternative explanations are not supported by the evidence and the rhetorical adduction model provides the best explanation of the move to recognize Bangladesh. For many states, despite their initial objections, recognition of the new nation of Bangladesh was made acceptable by the withdrawal of Indian troops from Bangladesh. Britain, India, and Bangladesh argued successfully that withdrawal meant that recognition would not violate norms of non-aggression, self-determination, or the international legal norm of effective control of territory. So, both the withdrawal and many recognition decisions were driven by rhetorical adduction.

Conclusion

The rhetorical adduction model is applicable to a relatively specific set of conditions that come together to produce a particular process of argument, counterargument, adduced action, and policy adoption. If rhetorical adduction can bolster normative arguments, we should be interested in the conditions under which it works. What are some possible sources of variation in the operation of this mechanism?

A useful comparison to success in the Bangladesh case can be made with another set of arguments concerning the nonrecognition of Russia's annexation of the Crimean peninsula in 2014. The Crimean case is a useful comparison because it too involved arguments over territorial integrity, secession, and self-determination, as well as appeals to the international community for recognition. The question is why the primary argument deployed by Russia and Crimean separatists—that a referendum on the secession proved that it constituted self-determination—failed to gain any traction, even among relatively disinterested parties. As outlined earlier, a crucial element of rhetorical adduction is that, to be convincing, the actions taken to support the argument must be a competent performance, that is, in accordance with the intersubjectively accepted conception of the action.

The attempt to support the argument that the Crimean secession and annexation was an act of self-determination by holding a referendum was clearly incompetent. This is despite the fact that many of the inhabitants of Crimea are Russian speakers, Crimea was a sovereign state in 1917, an autonomous Soviet Socialist Republic from 1921 to 1945, part of Russia from 1945 to 1954, and an autonomous Republic within Ukraine from 1992.Footnote 127 There was a potentially convincing argument to be made that transferal of Crimea from Ukraine to Russia was an act of self-determination. The Supreme Council of Crimea issued a declaration of independence on 11 March 2014 and subsequently held a referendum on whether Crimea should become part of Russia.Footnote 128 Various Russian leaders, including Russian President Vladimir Putin during a telephone call to US President Barack Obama, asserted that the referendum was “legal and should be accepted.”Footnote 129 The day after the referendum, Putin signed an executive order using the referendum as the sole justification for recognizing the Republic of Crimea.Footnote 130 However, there were numerous objections to the referendum. Some of the most prominent concerned the form of the referendum (the questions, the timing, and its status under municipal law), the lack of independent election observers, the fact that intimidation and coercion were suspected because of the presence of armed Russian or pro-Russian forces, and doubts over the results.Footnote 131 Numerous states and IOs claimed that the referendum's lack of validity supported their argument against recognition, including in a UNSC draft resolution vetoed by Russia (S/2014/189), as well as the General Assembly Resolution 68/262 on the Territorial Integrity of Ukraine.Footnote 132

We can explain the failure of argumentation to change the normative status of the annexation of Crimea via the incompetent performance of the primary action taken as part of rhetorical adduction. An implication of this claim is that had the Crimean separatists made the referendum conform more closely to the intersubjective definition of a free and fair election, it would have been more convincing to the audience and much harder to dismiss by those implacably opposed to Russia's actions.

More speculatively, we can draw out several features of the situation that affect whether the full process of rhetorical adduction plays out. Only if the audience is valuable to the claimant and opposition is it worth trying to win their support. Only if the audience is relevant to the success of the policy will winning them over have any effect on whether the policy gets adopted. So, a source of variation is the value of the audience to the policy. The audience may vary in terms of how susceptible they are to a reframing of the situation. The more a situation is new or unprecedented, the more important rhetorical action is in constructing the properties of that situation, and hence the more consequential rhetorical adduction will be in bolstering the acceptability of a particular construction. Maybe there are principles at stake in the contestation. That is, some situations bear on questions that are relatively unsettled in society, where the norms and rhetorical commonplaces are relatively less taken for granted and hence more up for grabs. Another vital source of variation is the ability of the arguer and counterarguer to come up with socially sustainable arguments and counterarguments within the constraints of the intersubjective stock of background knowledge and rhetorical commonplaces. Scholars may be able to spend large amounts of time and effort coming up with plausible frames of situations, but the ingenuity of political actors in trying to construe events and ideas to their advantage is constantly surprising. The character and skill of individual people is another source of variation in the potential for rhetorical adduction both to be attempted and to be successful or otherwise.

I have proposed a specific type of mechanism through which normative argumentation can have a causal impact on important actions in international politics. In doing so, this article both adds to those already identified, for example, persuasion, rhetorical entrapment, and rhetorical coercion, and also provides avenues for further exploration of how rhetoric and argumentation shape the actions of states. By linking reason-based choice theory with argumentation theory, the article provides an enriched framework for understanding what effects argumentation can have and how it has them. Thus it both avoids obscuring argumentation's impact by limiting it to those rare situations of power- and interest-free truth seeking, and also allows for the detailed specification of other types of effects. While I have used the idea of changing an action's normative status, such as redefinition as an excused exception to a norm, there are plausibly many other ways of influencing the reasons for or against an action. There is much room for further research on this topic.