Abstract

In this paper, we examine engagement with ‘the rural context’ in Australian education research, focussing on the implications of the signifier ‘rural’—in terms of its inclusion or absence. A review of Australian research literature in rural education indicates that the term ‘rural’ and its synonyms are more often used to denote assumptions of a generalised and predetermined ‘context’ for research than to think about its meaning. We present our findings here and discuss the implications of the signifier ‘rural’ in the Australian research literature to argue that while educational policy-makers must attempt to think differently about the 'problem of the rural’, the field itself also needs to more fully develop the capacity to do this.

Similar content being viewed by others

Avoid common mistakes on your manuscript.

Introduction

Like many researchers concerned with rural education, we (the authors) have all lived in rural areas and attended or taught in small rural schools. Philip has recently travelled back to the small remote town where he spent five years as a secondary teacher, enjoying several conversations with people he had taught over 15 years ago. Many now have families, and their own children attend the community school, so talk naturally turned to the school and education. Discussing these conversations with us on his return, we felt an unsettling sense of déjà vu that raises a challenge for us as rural education researchers. Philip’s former students are now raising the same issues their own parents had raised. They strongly resonate with concerns raised by teachers and principals in rural, regional and remote schools over several decades—the same systemic issues still confronting departmental officers responsible for staffing and supporting rural schools. It is clear that ‘nothing has changed’.

Key for parents are concerns about the retention of staff, access to specialist services and subjects, and the lack of understanding of their children’s lives that so many teachers exhibit (Halsey, 2017). Key for teachers are similar concerns about staffing and access to services, about opportunities and pathways for their students, and what they often describe as the ‘disadvantage’ of the communities they are working in (Halsey, 2017). Overarching these is perennial public commentary about poor student performance and low aspirations, all implicitly compared to the national norm.

Our uneasiness led us to ponder why, with so much research and educational innovation in Australia, we have not been able to generate a different narrative for education beyond the major cities. How and why has our history of research for rural schools (and for teacher education that might better prepare teachers for them) seemingly failed to make a difference? These are the questions we address here, speaking from a ‘rural standpoint’ (Roberts, 2014). And at a time when the Report of the 2018 Independent Review into Regional, Rural and Remote Education claimed that “focussing on ideas and options for re-thinking and reframing education in regional, rural and remote areas is likely to be more productive than simply concentrating on ‘the problems’” (Halsey, 2018, p.9), we are forced to reconsider the achievements and directions of work in the field of rural educational research to date. In what follows we argue that while educational policy makers are attempting to ‘think differently’ about the 'problem of the rural', we may need to do the same as researchers. Our review of Australian research literature in rural education shows that as a field we have not yet developed the capacity to do this.

Framing an interrogation of rural education research

Like most rural educational researchers in Australia, we have committed to this field because of our own history, geography, and the concerns for social justice we have developed as practitioners. Many also believe that attention to the rural allows us to understand urgent global environmental issues as profoundly educational issues that require us to rethink education ‘from the margin’. We are typically educators first, and our theoretical resources for interrogating even our own assumptions about the rural are often pragmatic and preconstructed, ‘received’ through our training and history in our own (only sometimes rural) social spaces. We do not see ourselves as sociologists or geographers per se—our focus is on education—though our research is typically associated with educational sociology and geography. Many of us also lack a lived sense of the Indigenous histories and knowledges of the land itself. Even though we may share an investment in, and recognition of, the importance of country, and its history, we are mainly non-Indigenous advocates, in pursuit of policy and practice that provides recognitional and distributional justice for non-metropolitan schooling.

Our inquiry positions rural education as a distinct sub-field in educational research. There is a long-established history of education academics identifying with rural education as their academic identity, supported by Special Interest Groups in the Australian, European and American Educational Research Associations and dedicated journals in Australia, North America and China (Roberts & Fuqua, 2021). Those that identify with the field tend, in our experience, to be influenced by place-based education (Gruenewald & Smith, 2014) and the spatial turn in social theory (Gulson & Symes, 2007). These have likely gained currency as they speak to the motivating ethic of many whose research shares a concern for rural people, places and communities, and a sense of ‘marginality’ from the metropole and metropolitan forms of education and valued knowledge.

What is ‘rural’?

The answer to this question is deceptively complex. As the rural geographer Cloke (2006, p. 2) argues, rurality is neither natural nor given. Instead, it is a product of the western academic disciplinary tradition. As educational researchers we have been disciplined to accept a binary logic of city/country; urban/rural; cultured/rustic; connected/isolated. After all, the trope of ‘rural as disadvantaged’ does have advantages for researchers—establishing ‘rural’ as ‘difference’ and constructing it as a research variable. Methodologically, however, this construction asks few, if any, questions about the rural and ‘rurality’, and allows us to work with the category as pregiven, generalised and static. Countering this, the perspective of a rural standpoint (Roberts, 2014) challenges the normalising tendencies and symbolic violence (Reid et al., 2010) of much educational research focussed upon rural schools (Roberts & Green, 2013). Here in Australia the need to engage rurality from a rural standpoint can be traced back to Sher and Sher’s (1994) call for researchers to really value rural, peoples and communities, with Brennan (2005) imploring the education research community to put rurality on the educational agenda, and Roberts and Cuervo (2015) outlining future directions for rural education research. This has culminated, to date, with Roberts and Fuqua’s (2021) volume Ruraling Educational Research.

Unpicking the implications of how the rural is defined (or not) in research, and developing theoretical tools for understanding the lived experience of being rural, has been a central preoccupation of rural studies, and its sub fields of rural geography and rural sociology. This work has been foundational to our own, and this present paper is directed towards advancing the development of a theoretical understanding of the ruralFootnote 1 for the field. Problematically, the rural is often studied as part of urbanisation—indeed as the outcome of urbanisation—thus reinforcing the relationship between the rural and the city (Shucksmith & Brown, 2019) and creating a structural proclivity to comparison between each. It is typically accepted in the broader fields that rurality is a complex concept requiring intersecting geographical, statistical, social, and cultural definitions (Reid et al., 2010; Roberts & Guenther, 2021). In a recent overview of the definitional debates in defining the rural, Shucksmith and Brown (2019) identified a distinction between social constructivist and structural/demographic approaches. Social constructivist approaches understand the rural as a social and cultural phenomenon that is produced, and distinct in and of itself. Alternatively, structural/demographic approaches understand the rural as constituted of measurable characteristics that can be compared to other places. Alternatively, Bollman and Reimer (2020) characterised a distinction between theoretical and operational variables, recognising that the rural can be expressed in qualitative terms of experience and value or measured and represented quantitatively through statistics.

Following on from the complexity of defining the rural are the affordances and limitations of the different methodologies they imply (Roberts, 2014; Roberts & Green, 2013). However, while the history of subaltern social theorising means that feminist and Indigenous standpoint theories are now widely accepted (Connell, 2014; Harding, 2004; Moreton-Robinson, 2013) a rural standpoint does not yet appear to have impacted on education research and policy more broadly. As Sher and Sher (1994) put it, rural people do not seem to “really matter” in metrocentric thinking. Rather, a statistical definition of the rural, based on geography and proximity to services (ABS, 2021) is operationalised in educational policy at the expense of more social and cultural definitions (Roberts & Green, 2013). This results in the rural being constructed as a category of difference—inherently comparable to elsewhere. We see this for instance in the near-universal reporting on rural educational achievement in Australia, where commentary is based solely on the statistical definitions of the ABS Remoteness structure that divides Australia’s geography into five categories of remoteness from ‘major cities’ through to ‘very remote’ (ABS, 2021).

The inherent comparison to the city that results from the use of statistical categories without a social or cultural dimension reinforces a metro-normativity (Roberts & Green, 2013) that we argue is inherently colonial. It is at odds with educational research that is increasingly responding to global environmental, economic, and social upheavals and the need for a general decolonisation of the Australian consciousness (Mills, 2018; Tuck et al., 2014; Vass, 2015). Such moves serve to emphasise the limitations of the ways in which we have naturalised rurality as social construct. As Azano & Biddle (2019) suggest “When urban and rural are reified without recognizing the historic relationships between them, the interdependence of rural, urban and suburban spaces, teachers and leaders continue to reproduce unhelpful dichotomies that thwart freedom” (p.9).

Recognising the dangers of ignoring the historical importance of rural communities and marginalised populations following the 2016 election, for instance, US researchers have made strong attempts to direct political attention to the rural (Brenner et al., 2020), and to rethink the nature of rural educational research in that context (Azano & Biddle, 2019; Biddle et al., 2019), yet this debate has not been taken up in the Australian field to date. We note here the impact of increasing political awareness of the need to acknowledge Indigenous ways of knowing country and connection and see this as a moment of opportunity to rethink rurality. From an Indigenous perspective, for instance, the very idea of ‘rurality’ might be seen as non-sense (Roberts & Guenther, 2021). Furthermore, recent voting trends in rural Australia are themselves reflective of changing political and cultural lines (Chan, 2018) and support the need to understand that rurality is neither an essential nor a universal category, but a profoundly sociological, historical construct. As a material reality for the nation though, rural, remote and regional people and places need to be governed. In this context, the Australian Education Research Organisation [AERO], the national evidence institute recommended by Gonski et al. (2018) has established ‘standards of evidence’ to assist practitioners, policy makers and other stakeholders determine the strength of evidence in research. These standards have timely implications for the need to have a working definition of the rural enacted in research.

The nature of evidence

AERO standards advocate that “when evidence is rigorous and relevant, it provides confidence that a particular approach is effective in a particular context” (AERO, 2021a, N.P.). Research rigour is described in terms of the methodological choices that will allow “the specific impact of a particular educational approach” to be isolated (AERO, 2021b, p.1), and the relevance of evidence arises when users see findings that are “produced in contexts that are similar to [their] own”, or that are alternatively “derived from a large number of studies conducted over a wide range of contexts, as this suggests that the educational approach is not dependent on any particular contextual factor” (AERO, 2021b, p.1). AERO explains the ‘Key Concept’ of ‘context’ as:

the social, cultural and environmental factors found in research settings. Taking context into account in research studies is important because context can affect the outcomes of research (i.e., evidence generated in one context may not necessarily apply to a different context). Evidence is most relevant when it has been generated in a context similar to the context in which it will be applied. Examples of ‘context’ may include location, demographics of research participants, or the level of organisational support for the particular approach being researched. (AERO 2021a, N.P, our emphasis)

Within this framework, a user can only have ‘very high confidence’ in evidence when inquiry “conducted in my context or other contexts similar to mine shows the approach causes positive effects” (AERO, 2021b, p.2). Yet to create policy, governments must make the assumption that ‘rural’ contexts are inherently alike—all ‘similar to’ each other—if they are to base their work on ‘research evidence’. As the continuing poor success of educational policies built from this research evidence indicates, however, rural contexts are not all the same, and this ‘evidence-based approach’ is yet to be successful.

Internationally, Howley et al. (2005) argued that rural meanings and perspectives are an essential component of rural education research, requiring the explicit foregrounding of rural meanings. Coladarci (2007) advocated for a ‘rural warrant’ for research, as a measure of the extent to which studies met this standard. In the Australian context, the conceptual relationships that characterise Reid et al.’s (2010) Rural Social Space model bring many of the dimensions of understanding rurality from the international rural studies field into categories that neatly overlay with the AERO’s (2021a) definition of context as “the social, cultural and environmental factors found in research settings”. But this model suggests that attention to the specificity of place can never be neat—and that for policy success, generalisations about the rural must be complexified by local considerations. Like Coladarci’s argument for a ‘rural warrant’, a rural standpoint highlights the problem that definitions of research relevance and rigour normalised in the AERO (2021a; 2021b) documents are place-blind and indicate large-scale lack of understanding of rurality among the research community. Finally, a review of US dissertations purported to be on rural topics noted the lack of genuine engagement with rural contexts and called for a meaningful use of rurality in line with the studies cited above (Howley et al., 2014).

That this debate remains ongoing suggests that many researchers find it difficult to challenge the power of established research practices.Footnote 2 Following Fendler (2006), and Roberts and Fuqua (2021), we argue that while the AERO (2021a) definitions of context are helpful for emphasising particularity, the nature of forms of evidence may themselves reinforce historicised, metronormative perspectives on evidence and the phenomena examined by research inquiry. In considering how we can best support educational policy makers, school leaders, teachers, and teacher educators to ‘think differently’ about the 'problem of the rural', we set out to examine what the field currently looks like. Thinking differently requires a strong conceptual framework, one that can work for reconciliation and restitution rather than remain within the received frame of western colonial thinking—which, as we appreciate, the term ‘rural’ itself, as a western, European, construction, reinforces.

Methodological framing

Our aim is to examine engagement with the rural ‘context’ in Australian education research, focussing on the implications of the signifier ‘rural’ in terms of its inclusion or absence in education research. Following Cloke and Johnson (2005, p.2) we ask: what forms of knowledge are produced by the categories we currently deploy in order to appreciate the social and material phenomena of rural schooling? Our approach and subsequent analysis is informed by the thought lines of the discussions referenced above. Through these we arrive at a position that rural (education) research needs to engage the complexities of rurality and be clear about how the rural is understood in the research being undertaken and/or reported. Furthermore, the research needs to engage this meaning in its analysis and methodology, and consider the impact the meanings used have on the understanding and interpretation of the phenomena being researched (Roberts & Green, 2013).

In presenting our analysis and the related discussion, we first note the ethical considerations involved in dealing with a current research field and its literature. The dilemma of naming articles, and authors, has led us only to reference examples of research that engages with the multiplicities of rurality (or clearly defined definitions of what constitutes rurality) in the study, so readers can see examples of this type of article and how the analysis has been informed. Given the pervasive deficit discourse around rural educational achievement we feel all authors are acting with ethical intent, and like ourselves, should not be criticised for being a product of their own (academic) habitus.Footnote 3 As noted above, the issue of how the rural is engaged with is a matter of wider social practice. For this reason we have treated the literature database as de-identified data in this report, and used general findings from that database to construct an overview of the field. As we have developed this database from published research specific ethics approval for the research was not required. Examples of articles that do not engage with the complexity of rurality have not been named, rather we have used examples of statements that summarise the approach to discussing rurality. We will, in subsequent work, engage in more detailed discursive exposition using this dataset. For now, the analysis reported here is the initial step in a larger, ongoing analysis of rural education research to identify definitional, methodological, thematic, and epistemological trends across the field.

Method

The aim of our analysis was to examine engagement with the rural ‘context’ in Australian education research, focussing on the implications of the signifier ‘rural’ in terms of its inclusion or absence in education research. We approached this analysis as a scoping review of education literature to identify where and how rural contexts have been used in reports of educational research, and what work they were doing as signifiers. A scoping review was more appropriate than a systematic review such as undertaken in the large Aboriginal Voices (Lowe et al., 2019) project, or a discourse analysis that would identify individual papers for several reasons: the exploratory nature of the review (Arksey & O’Malley, 2005; Peters et al., 2020); the broad inclusion criteria we used in the review (Arksey & O’Malley, 2005; Higgins & Green, 2011); and our focus on the characteristics of the research available. The scoping review does not aim to provide the critical analysis and synthesis of individual research studies as would a systematic review, nor does it trace the meanings and power effects of usage over time as would a discourse analysis (Poynton & Lee, 2000).

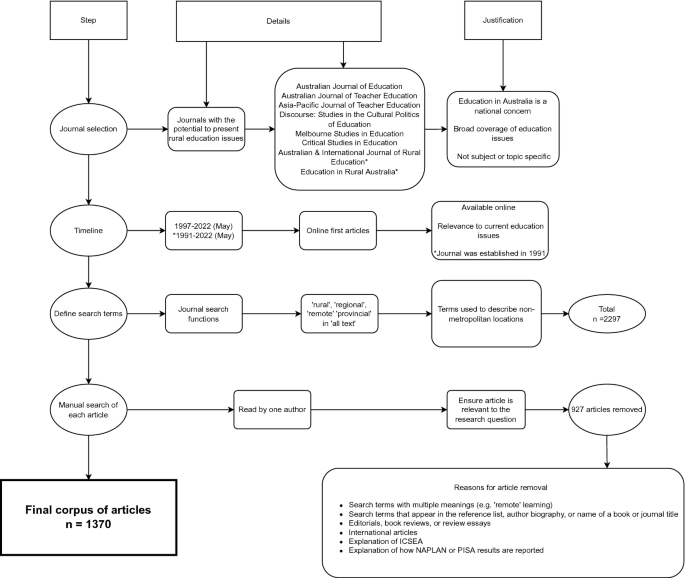

Strict criteria were developed and followed for journals to be considered in the review and the screening and analysis process of the articles, to ensure the transparency and replicability of analysis (DiCenso et al., 2010). Figure 1 provides a summary of the criteria for the inclusion of articles in the scoping review.

All education journals with the potential to cover issues related to rural education in Australia were included in the scoping review, including the six major sociologically-orientated research journals that do not maintain a specific disciplinary focus. These were the Australian Journal of Education, Australian Journal of Teacher Education, Asia–Pacific Journal of Teacher Education, the Australian Education Researcher, Discourse, and Critical Studies in Education (which prior to 2006 was known as Melbourne Studies in Education). The national focus recognises that the rural is constructed, and education is organised, at a national scale. Indeed, the particulars of how the rural is understood in Australia are such that, for the purpose of this analysis, a national boundary is essential to engage a national policy context. The Asia–Pacific Journal of Education was initially considered for inclusion in the sampling, however because it is nominally located in Singapore and has relatively few articles that relate to Australia we considered its inclusion at this stage of the research unwarranted. We initially predicted that Discourse (and more recently Critical Studies) may have been excluded for a similar reason, however, we observed many articles relating to Australia, by Australian authors, and relating to rural education. Every Australian article in the single Australian rural education journal, the Australian and International Journal of Rural Education (which until 2012 was called Education in Rural Australia) was included due to its focus on rural education.

Journals from the year 1997–May 2022, including any available on journal databases as ‘online first’ articles, were included in the analysis of the non-rural specific journals. 1997 is the year that most journals in this analysis became available online, and this period covers almost a quarter of a century of publications. We considered that research more than 25 years old is less likely to impact on current education policy and research. Full texts of some articles in some early editions (1997–1999) were not available using online databases, requiring us to source paper copies to ensure a consistent starting point.

All Australian articles from both iterations of the rural education journal were considered eligible in the initial screening process because of its espoused rural education focus. In this instance the inclusion period started with the Journal’s inception in 1991 to ensure full coverage of this topic specific journal, noting it began as a small volume journal. All issues in the six main journals were screened to identify articles that related to rural education. These were identified using the journal database search tool, where the full text was searched for the key words ‘rural’, ‘remote’, ‘regional’ and ‘provincial’. These words were selected as the main means of describing ‘non-metropolitan’ locations in Australia within the binary logic of what Roberts and Green (2013) call ‘metrocentric’ inquiry. These were the exact search terms used, with no variations or Boolean search delimiters used due to the specific meanings of these search terms. The terms ‘rural’ and ‘remote’ for example, do not have any possible ways to be shortened. The term ‘region’ connotes a much larger meaning base than ‘regional’, as can the term ‘provic*’ rather than ‘provincial’. Individual searches were completed for each of the search terms rather than completing one search for all four terms. Each result is reported on individually in this step of the search process.

The results from this step of the screening process are outlined in Table 1 below.

Each article was then manually screened by one of the researchers to ensure it was relevant to the purpose of the study. Articles were removed if they did not relate to education in rural Australia, which was particularly important due to the possible multiple meanings of the search terms ‘regional’ and ‘remote’. For example, articles containing the term ‘remote’ when it was used to reference ‘remote control’, ‘distant’, or the separation of someone, were not considered relevant to the analysis and therefore excluded. We also excluded articles containing the term ‘regional’ when the term was used to refer to a ‘regional office’ that may have been in a metropolitan location, such as Western Sydney regional office, and regions around the world. Articles were excluded when search terms only appeared in the reference list, the author biography, or in the name of a book title or journal title. Editorials, book reviews, and review essays were removed as they were considered reviews of other sources of research about rural education, and international articles were removed because they did not focus on education in rural Australia. Articles that only referenced the search terms as part of a definition or formula were removed because they did not relate to rural education specifically. This included articles referencing how NAPLAN or PISA results are divided or how ICSEA is calculated but not discussing results of rural schools. Duplicate articles were also removed in this screening process. Table 2 below outlines how many articles met the criteria for analysis.

After the initial screening process, articles were manually analysed according to how they used the search terms. This required both a hermeneutic and a descriptive approach using qualitative content analysis (Hsieh & Shannon, 2005). Content analysis is “a research technique for making replicable and valid inferences from texts (or other meaningful matter) to the contexts of their use” (Krippendorff, 2004, p. 18). This approach is important as a simple corpus count of word-usage would not identify themes within the different ways that ‘rural’ was used and defined. Qualitative analysis of the context and thematic patterns in use of the terms ‘rural’, ‘regional’, ‘remote’, and ‘provincial’ further enabled a focus on identifying the themes in articles, to identify patterns in approaches to research in rural education. It also enabled changes over time to become evident in the patterns of use of key terms in each journal. Content analysis approaches are becoming more common to assess the development of research fields and disciplines and have recently been used to explore the discipline of sociology in Australia (Collyer & Manning, 2021), and the rural studies field (Strijker, et al., 2020). Manual analysis approaches are more effective than using textual analysis software as they can more effectively identify nuances in meanings, definitions, and context than software (Collyer, 2014).

The final stage of the content analysis drew on a deductive approach where the categories for analysis were determined based on the concepts and debates about valuing the rural in the literature cited above. The first category included articles that both identified and valued the complexities of rurality through intersecting geographical, statistical, social and cultural definitions (Reid et al., 2010; Roberts & Guenther, 2021), and that discussed rurality as having meaningful impact on the phenomena being researched in the analysis (Roberts & Green, 2013). We erred on the liberal side of interpretation here as we appreciate some of the conceptual developments that framed our discussion were new and may well be outside the typical frame of many researchers. We acknowledge that ‘category one’ aligns with the approach we advocate, based on our theoretical positioning and our motivations to undertake this study. However, as much as a human can, we set-aside our preferences in the analysis and remained critical of each other’s analysis to ensure we did not pre-populate this category. Articles assigned to the second category reported studies that either did not define the rural or did not engage with the complexities of rurality in either definition or analysis. After sorting into these two categories, articles were further analysed to identify themes in the topics studied, methodology used and the framings of the studies.

Findings

Table 3 outlines the results from each stage of analysis. In the following sections we provide an overview of the types of articles that were in each category. An overwhelming number of studies in the analysis fell into Category two, as they did not identify and consider how the rural is constituted in their descriptions of rurality, nor did they engage with how the rural is constructed in their methodology, method, and subsequent analysis.

Overall, only 2.4% of the 1012 articles in the general education journals considered the complexities of rurality in their definitions and analysis. In the rural education journal only 18.4% of articles did this—and it is significant that many of the articles in category one in the Australian and International Journal of Rural Education were from a special edition that focussed on the importance and implications of valuing and considering rurality, thus increasing the numbers in this category.

Category one: articles that identify and consider the complexities of rurality

Research articles in this category focussed on highlighting why it matters that rurality is valued in education and on the need to challenge the notion of rural disadvantage. They fit with the proposition that research needs to meaningfully engage with rurality to genuinely represent phenomena germane to its context. They drew on models of rurality such as the rural social space model (Reid et al., 2010) to foreground the notion that rurality influences students’ education and that many perceived educational ‘problems’ are constructed through the operation of a metrocentric education system. The need to consider specific economic and social conditions, and the impact of rural change on education were also key considerations. Examples here include consideration of rural place attachment and opportunities for careers in rural communities; the importance of valuing rurality in school and teacher education; and how these contribute to rural sustainability. Articles challenging deficit discourses identified the role of systemic inequities, standardised policy, curriculum, assessment, and out-of-school service provision as systemic barriers to educational achievement that were beyond the school or the rural child. Three examples of how articles engaged with definitions of rurality are provided in Table 4, below.

Whilst a form of rural advocacy certainly dominated this category, there was a stark absence of work focussed on engaging rurality in the process of education. The closest thing to examining how rurality influences the conceptual and material processes of education would be the research theme of place-based education (Gruenewald & Smith, 2014), which is often concerned with environment, history, and culture. However, many of these studies substituted ‘place’ for ‘rural’ and did not engage rurality beyond the coincidence of location. We conclude that there is a clear opportunity for the development of this theme and the generation of evidence-informed articles that more deeply engage rurality within the processes of education.

Category two: articles that do not identify or consider the complexities of rurality

Papers assigned to this category used the signifiers for ‘rural’ across a wide range of topics including teacher education, professional development for teachers, Indigenous education, post-school education, leadership, early childhood, online and distance education, and student aspirations and careers—all addressing the issue of the rural but not meeting the standard of valuing rurality needed for inclusion in category one. Instead, we found reference to ‘rural’ places, and ‘rural’ schools and children, used in six different ways, all of which failed to recognise the complexities and affordances of rurality as context.Footnote 4

Using rural as a marker of location

In most Category 2 papers ‘rural’ was merely used as a marker of location for the school or university that housed the research. Other than noting the study’s location in a rural school, the term ‘rural’ (or related signifier) was often not used again in the article, or, if it was, appeared only in the conclusion to highlight rural disadvantage. These studies presented no evidence that the issues they studied were influenced by, or relevant to, the rurality of the research site in any way, and gave no indication that their findings would not have been evident in a metropolitan school. That the site was ‘rural’ was often the sole basis for the article’s claimed contribution as ‘new knowledge’ or its inclusion in the rural education journal. Topics in this category included studies of pre-service teachers learning about a specific literacy intervention; an activity to raise student aspirations; and professional development activities for teachers. Examples of such statements included ‘This study occurred in a regional university’, ‘The professional development program occurred in a rural school 245kms northwest of Sydney’, and ‘Six rural schools participated in this study’.

Rural disadvantage

‘Rural disadvantage’ was often cited as a justification for studies in rural schools and communities. Over time, delineable increases in studies follow public reports on rural disadvantage were discernible—e.g., the Human Rights and Equal Opportunity Commission Report (HREOC, 2000); the report of the Bradley Review (2008); and the Independent Review into Rural Regional and Remote Education (Halsey, 2018). These studies are predicated upon ‘disadvantage’ against an implicit metropolitan norm (Guenther, 2015; Roberts & Green, 2013), typically in terms of outcomes in the National Literacy and Numeracy testing, PISA, TIMSS, or university matriculation figures. Some studies aimed to address this by providing rural schools with access to programs or supports to meet the standard of metropolitan schools and communities (in the same terms as those communities). Examples include literacy interventions to increase students’ test scores, programs to give students access to music facilities, and online programs for students who do not have specialist teachers in their school. Other research in this category focussed on identifying further markers of rural disadvantage based on studies in other locations: including student perceptions about access to opportunities in their communities, accounts of teachers’ experience of out-of-field teaching, and student aspirations for university study. Examples of how articles referred to the rural in this category included ‘A rural school was chosen for the professional development program because rural students have lower scores in the NAPLAN program’, and ‘Rural teachers are more likely to teach out of field and experience challenges associated with content knowledge and professional isolation’.

While it is obviously important to highlight vectors of disadvantage to inform policy and practice, we found that studies classified in this category take rural disadvantage as given. What constitutes the rural, and how advantage and disadvantage is understood, yet alone produced by metro-normativity, is overlooked. Instead, ‘rural disadvantage’ becomes a justification for the study. By reproducing deficit discourses and, assuming that students and their families are deprived rather than different, such research enacts a symbolic violence upon (all) rural students and communities. Again, in most ‘intervention’ studies here, pre-existing solutions introduced to a ‘new’ context were claimed to demonstrate educational innovation.

Research sample justification or comparative category of analysis

Many studies included rural schools in their research samples to highlight that a diversity of school locations had been included in the design. Such studies usually made no reference to rural schools outside the ‘method’ section. Most of these articles were using a sample of metropolitan and rural schools to infer validity of findings, an essentialisation that cannot be sustained. Studies in which rural schools were discussed in the analysis mainly highlighted differences from metropolitan schools. Most of these articles used quantitative methodologies with ‘rural’ as a statistical category of variance only, with implicit reference always to a metropolitan norm (Roberts & Green, 2013), and no test of representative weightings undertaken. Examples of usage in this manner include ‘We surveyed teachers from major cities, inner regional, outer regional, remote, and very remote locations’ and ‘Statistical analysis showed differences in results between students located in major cities and those located in regional and remote locations’.

Descriptive studies

Research in this category focussed on reporting the results of programs implemented in rural schools and included the evaluation of teaching innovation; school wide policy change; online education programs, and professional development programs in rural schools. Example statements here include ‘We trialled a professional development program in with twenty rural schools’ and ‘After the completion of the STEM careers program students in remote schools felt they knew more about university’. Overwhelmingly qualitative self-report studies, they focussed on describing the program, the results of the program and how it was evaluated by those involved. Many of these interventions only occurred over a brief period and with a small number of participants, with little follow up beyond the implementation. These studies lacked a focus on theoretical advances in rural education and their prevalence suggests that although there are numbers of intervention programs occurring in rural schools, few aim to increase knowledge or understanding ‘in and for’ the rural (Roberts & Fuqua, 2021; White & Corbett, 2014).

Generalising diversity

Use of the term ‘rural’ alongside other labels such as ‘low SES’, ‘diversity’, and ‘Indigenous’ marked the articles in this category. As with the ‘rural sample group’, these labels were mainly used to demonstrate that a diverse sample of participants had been drawn upon, and claim generalisability for the studies, and by inference the validity of findings. Examples of such statements included ‘Teachers from a range of different school settings including schools with high populations of low SES, remote, EALD, and Indigenous students responded to the survey’, and ‘Rural, and low SES students are less likely to attend university so we implemented a program to support them to learn about university and post school careers’. Ignoring the particularities of the research site essentialises rurality and undermines the use value of the findings.

Articles focussed upon issues specific to rural schools

We noted above that there are very few evidence-informed articles that engage rurality within day-to-day education processes. Articles classified in this category focussed on issues specific to rural schools without engaging with rurality. Instead, the focus was on the phenomenon which, although not interrogated as an inherently rural issue, is unlikely to occur elsewhere. Examples include youth out-migration; ICT and teaching to connect students to opportunities not available in their school; increasing isolated students’ aspirations for higher education; and issues of isolation and Indigeneity in remote schools. Other than identifying the site/s, the specificity of such ‘rural’ phenomena was ignored, reinforcing narratives of disadvantage relative to the implicit norm of the metropolitan experience. Examples here include ‘teachers at regional and remote schools are more likely to experience professional isolation so we developed an online network to support them’, and ‘students in remote and rural locations are less likely to access arts and cultural programs so a university connected with a remote school to give them access to a dance program’.

In our discussion below, we aim to identify trends in the nature and type of these studies to highlight the effects of inquiry that does not effectively engage rurality. Many articles in this category have been used in subsequent academic studies and have influenced policy and practice. From a rural standpoint, however, we see that rurality is neither germane to the research, nor interrogated in its analysis. Claiming to produce knowledge about rural people and places in this sense is at the heart of our concerns about the veracity and value of education policy and practice.

Discussion

We explained earlier our own use of the term ‘rural’ as marker for all its synonyms but need to point out the problem created when such decisions are not explained. When generalising diversity, the terms are often used interchangeably. For example, ‘remote’ was often used to reference ‘Indigeneity’ where a study may have occurred in a remote school but was predominantly focussed on Indigeneity. There was a marked absence of engagement with First Nations in relation to rural and regional education research. Instead, ‘remote’ appears to have been ceded to this focus, with ‘rural’ and ‘regional’ rendered devoid of First Nations people—something which is both inaccurate and concerning.Footnote 5 ‘Rural’ was also often used interchangeably with, or for, ‘low SES’, where research about low SES was used as the justification for a study occurring in a rural school, or vice versa. In such cases it became unclear which of these factors was relevant to the findings.

Interrogating ‘the rural’ in research is always an ethical issue (Downes et al., 2021; Roberts & Fuqua, 2021; White & Corbett, 2014). In mapping the trajectories of rural education research our aim was to interrupt the cyclic déjà vu of review and intervention directed at ‘solving’ the rural school problem in Australia. We did not imagine that our findings would be so stark—leading us to argue that the ‘problem’ of rural education continues in part because our field has not yet engaged with the ethical responsibility of addressing the meanings of rurality in the conceptualisation and construction of research. Our methods and methodology, and our interpretation of findings do not yet appear to value rural people, and rural schools, for what they are: this is endemic, unjustified, and ultimately discriminatory.

While AERO helpfully articulates the importance of context as a significant feature of high-quality evidence for educational research (AERO, 2021a, N.P.), our analysis shows the significance of engaging the rural as context is too often absent, so that opportunities to advance our understanding of rurality and education are hindered. The recent Independent Review into Rural Regional and Remote Education (Halsey, 2018) is a pertinent example of this. When examined alongside our findings here, critical analysis shows that little research with a ‘rural warrant’ informed this review (Roberts & Fuqua, 2021). Instead, most references are open-access reports by thinktanks on student outcomes, or research that fell in our ‘non-rural’ category. And it has again resulted in a predicable burgeoning of new research to solve the ‘problem’ it described. The rural, we contend, must be more than a site for research based on pre-existing findings ‘taken bush’ to be tested with a different category of students. Instead, educational research needs to understand and foreground the nature of its object, and how a problem is produced, in any place.

Further, we argue that rural research must be more than research about education in rural places. It must be rooted in place—research in, for and with rural people and communities (Roberts & Fuqua, 2021; White & Corbett, 2014). While it may seem obvious, researchers cannot bring pre-existing solutions to a ‘problem’ as defined from elsewhere. Understanding that ‘rural’ cannot be essentialised as a single category (Reid et al., 2010), we propose that research needs to define its terms, relate those terms to the phenomena being examined, establish a methodological link and engage with that alignment in their method and analysis. Without this the research will reinforce the forms of symbolic violence produced by metro-normativity (Roberts & Green, 2013) and reproduce the ‘geographic narcissism’ (Fors, 2018) that characterises it:

I saw the damage one can do when applying the wrong “map” to a misunderstood place and how hard it is to acknowledge that one’s assumed center is not the navel of the world. (Fors, 2018, p. 446)

This does not mean recourse to formulaic acknowledgement or definition. Instead, we can learn from other fields where this is already well understood in the maturity of understanding and care for the complexity and diversity of rural places evident in most rural studies scholarship.

Conclusion

We write as three generations of academics connected variously as mentor, supervisor and supervisee pursuing the same concern for rural communities as generations before us. As members of and advocates for rural communities, this research has been motivated by an intent to support the ‘rethinking’ necessary to recast rural education as central to the sustainability of our nation. We have chosen to focus attention on the background to the study and its methodological approach rather than deep elaboration of our findings—partly due to the confines of space, but also because we believe an overview of the field is more coherent and useful as a foundation for subsequent work.

We appreciate the ease with which we can inadvertently fall into metro-normativity and reproducing rural disadvantage. We hope that by drawing these discussions to the reader’s attention we have invited you to engage them in your research. As we highlight in this analysis, researchers that engage with rural communities must move beyond the idea that there is ‘a’ rural Australia. Our inability to understanding this multiplicity and complexity is one of the key issues, we argue, that causes and maintains educational inequities in Australia. The binary logic of our western tradition teaches us to think of social relationships as natural, linear, and reflecting the centrality of human progress in terms of causal effect (Connell, 2014). Inside this logic much education research categorised as ‘rural’ has ignored the eco-social, mutually constitutive relationships of people, place and power, and works with a focus on rural populations as a category of difference, ‘a group’ that is ‘other’ than a metropolitan norm. To counter this we advocate that to really value rural people, places and communities, research needs to engage with the complexity of rurality (Reid et al., 2010; Roberts & Guenther, 2021).

Notes

Rural is used in this paper as a collective term for all non-metropolitan categories, such as regional, remote, country.

Indeed, most studies reflect the ethic of beneficence—although viewed ‘from the margins’, this might be seen as a form of benign benevolence that is inadvertently doing harm.

Returning to the methodological framing outlined above, examples of articles that do not engage with the complexity of rurality have not been named, rather we have used examples of statements that summarise the approach to discussing rurality.

To reinforce this point one of the authors was initially involved in the Aboriginal Voices project (Lowe et al., 2019) using the published methodology to search ‘rural’ and its synonyms, but excluding ‘remote’, which was the focus for Guenther et al. (2019). At the time only four articles eligible for inclusion were located making publication impracticable but influencing this study.

References

Arksey, H., & O’Malley, L. (2005). Scoping studies: Towards a methodological framework. International Journal of Social Research Methodology, 8(1), 19–32. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.mex.2021.101375

Australian Bureau of Statistics. (2012). Remoteness structure. Retrieved from http://www.abs.gov.au/websitedbs/D3310114.nsf/home/remoteness+structure

Australian Bureau of Statistics. (2020). Remoteness structure. Retrieved from https://www.abs.gov.au/websitedbs/D3310114.nsf/home/remoteness+structure

Australian Bureau of Statistics. (2021). How does the ABS define urban and rural? Frequently Asked Questions, Statistical Geography. https://www.abs.gov.au/websitedbs/d3310114.nsf/home/frequently+asked+questions#Anchor7

Australian Education Research Organisation. (2021a). Key concepts explained. https://edresearch.edu.au/key-concepts-explained#context

Australian Education Research Organisation. (2021b). Standards of evidence. https://edresearch.edu.au/standards-evidence

Azano, A. P., & Biddle, C. (2019). Disrupting dichotomous traps and rethinking problem formation for rural education. The Rural Educator, 40(2), 4–11. https://doi.org/10.35608/ruraled.v40i2.845

Biddle, C., Sutherland, D. H., & McHenry-Sorber, E. (2019). On resisting “awayness” and being a good insider: Early career scholars revisit Coladarci’s swan song a decade later. Journal of Research in Rural Education, 35(7), 1–16. https://doi.org/10.26209/jrre3507

Bollman, R. D., & Reimer, B. (2020). What is rural? What is rural policy? What is rural policy development? In M. Vittuari, J. Devlin, M. Pagani, & T. Johnson (Eds.), Routledge handbook of comparative rural policy (pp. 9–26). Routledge.

Bradley, D., Noonan, P., Nugent, H., & Scales, B. (2008). Review of Australian higher education: Final report [Bradley review]. Department of Education, Employment and Workplace Relations (DEEWR).

Brennan, M. (2005). Putting rurality on the educational agenda: Work towards a theoretical framework. Education in Rural Australia, 15(2), 11–20.

Brenner, D., Biddle, C., & McHenry-Sorber, E. (2020). Rural education and election candidates: Three questions. (Policy brief). The Rural Educator, 41(2), 70–71. https://doi.org/10.35608/ruraled.v41i2.1100

Chan, G. (2018). Rusted off: Why country Australia is fed up. Penguin.

Cloke, P. (2006). Conceptualizing rurality. In P. Cloke, T. Marsden, & P. Mooney (Eds.), Handbook of rural studies (pp. 18–28). Sage Publications.

Cloke, P., & Johnson, R. (2005). Deconstructing human geography’s binaries. In P. Cloke & R. Johnson (Eds.), Spaces of geographical thought: Deconstructing human geography’s binaries (pp. 1–20). Sage Publications.

Coladarci, T. (2007). Improving the yield of rural education research: An editor’s swan song. Journal of Research in Rural Education, 22(3), 1–9.

Collyer, F. (2014). Sociology, sociologists and core–periphery reflections. Journal of Sociology, 50(3), 252–268. https://doi.org/10.1177/1440783312448687

Collyer, F., & Manning, B. (2021). Writing national histories of sociology: Methods, approaches and visions. Journal of Sociology. https://doi.org/10.1177/14407833211006177

Connell, R. (2014). Using southern theory: Decolonizing social thought in theory, research and application. Planning Theory, 13(2), 210–223. https://doi.org/10.1177/14730952134992

Dalley-Trim, L., & Alloway, N. (2010). Looking “outward and onward” in the outback: Regional Australian students’ aspirations and expectations for their future as framed by dominant discourses of further education and training. The Australian Educational Researcher, 37(2), 107–125.

DiCenso, A., Martin-Misener, R., Bryant-Lukosius, D., Bourgeault, I., Kilpatrick, K., Donald, F., Kaasalainen, S., Harbman, P., Carter, N., Kioke, S., Abelson, J., McKinlay, R. J., Pasic, D., Wasyluk, B., Vohra, J., & Charbonneau-Smith, R. (2010). Advanced practice nursing in Canada: Overview of a decision support synthesis. Nursing Leadership, 23, 15–34. https://doi.org/10.12927/cjnl.2010.22267

Downes, N., Marsh, J., Roberts, P., Reid, J., Fuqua, M., & Guenther, J. (2021). Valuing the rural: Using an ethical lens to explore the impact of defining, doing and disseminating rural education research. In P. Roberts & M. Fuqua (Eds.), Ruraling education research: Connections between rurality and the disciplines of educational research (pp. 265–286). Springer.

Fendler, L. (2006). Why generalisability is not generalisable. Journal of Philosophy of Education, 40(4), 437–449. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1467-9752.2006.00520.x

Fors, M. (2018). Geographical narcissism in psychotherapy: Countermapping urban assumptions about power, space, and time. Psychoanalytic Psychology, 35(4), 446–453. https://doi.org/10.1037/pap0000179

Gibson, S., Patfield, S., Gore, J. M., & Fray, L. (2021). Aspiring to higher education in regional and remote Australia: The diverse emotional and material realities shaping young people’s futures. Australian Educational Researcher. https://doi.org/10.1007/s13384-021-00463-7hreox

Gonski, D., Arcus, T., Boston, K., Gould, V., Johnson, W., O’Brien, L., Perry, L., & Roberts, M. (2018). Through growth to achievement: Report of the review to achieve educational excellence in Australian schools. Department of Education and Training. https://docs.education.gov.au/documents/through-growth-achievement-reportreview-achieve-educational-excellence-australian-0

Gruenewald, D. A., & Smith, G. A. (Eds.). (2014). Place-based education in the global age: Local diversity. Routledge.

Guenther, J. (2015). Analysis of national test scores in very remote australian schools: Understanding the results through a different lens. In H. Askell-Williams (Ed.), Transforming the future of learning with educational research (pp. 125–143). IGI Global. https://doi.org/10.4018/978-1-4666-7495-0.ch007

Guenther, J., Lowe, K., Burgess, C., Vass, G., & Moodie, N. (2019). Factors contributing to educational outcomes for First Nations students from remote communities: A systematic review. The Australian Educational Researcher, 46(2), 319–340. https://doi.org/10.1007/s13384-019-00308-4

Gulson, K. N., & Symes, C. (2007). Spatial theories of education policy and geography matters. Routledge.

Halsey, J. (2017). Independent review into regional, rural and remote education—Discussion paper. Commonwealth of Australia. https://www.education.gov.au/teaching-and-school-leadership/resources/discussion-paper-independent-review-regional-rural-and-remote-education

Halsey, J. (2018). Independent review into regional, rural and remote education—Final report. Commonwealth of Australia. https://www.education.gov.au/quality-schools-package/resources/independent-review-regional-rural-and-remote-education-final-report

Harding, S. G. (Ed.). (2004). The feminist standpoint theory reader: Intellectual and political controversies. Psychology Press.

Higgins, J., & Green, S. (2011). Cochrane handbook for systematic reviews of interventions. The Cochrane Collaboration.

Howley, C., Howley, A., & Yahn, J. (2014). Motives for dissertation research at the intersection between rural education and curriculum and instruction. Journal of Research in Rural Education, 29(5), 1–12.

Howley, C. B., Theobald, P., & Howley, A. A. (2005). What rural education research is of most worth? A reply to Arnold, Newman, Gaddy and Dean. Journal of Research in Rural Education, 20(18), 1–6.

Hsieh, H. F., & Shannon, S. E. (2005). Three approaches to qualitative content analysis. Qualitative Health Research, 15(9), 1277–1288. https://doi.org/10.1177/10497323052766

Human Rights and Equal Opportunity Commission (HREOC). (2000). Education access: National inquiry into rural and remote education. Commonwealth of Australia.

Kline, J., & Walker-Gibbs, B. (2015). Graduate teacher preparation for rural schools in Victoria and Queensland. Australian Journal of Teacher Education, 40(3), 68–88. https://doi.org/10.14221/ajte.2014v40n3.5

Krippendorff, K. (2004). Content analysis: An introduction to its methodology. SAGE.

Lowe, K., Tennent, C., Guenther, J., Harrison, N., Burgess, C., Moodie, N., & Vass, G. (2019). ‘Aboriginal Voices’: An overview of the methodology applied in the systematic review of recent research across ten key areas of Australian Indigenous education. The Australian Educational Researcher, 46(2), 213–229. https://doi.org/10.1007/s13384-019-00307-5

Mills, M. (2018). Educational research that has an impact: ‘Be realistic, demand the impossible.’ The Australian Educational Researcher, 45(5), 569–583. https://doi.org/10.1007/s13384-018-0284-9

Moreton-Robinson, A. (2013). Towards an Australian Indigenous women’s standpoint theory: A methodological tool. Australian Feminist Studies, 28(78), 331–347. https://doi.org/10.1080/08164649.2013.876664

Osborne, S., & Guenther, J. (2013). Red dirt thinking on aspiration and success. The Australian Journal of Indigenous Education, 42(2), 88–99.

Peters, M. D., Marnie, C., Tricco, A. C., Pollock, D., Munn, Z., Alexander, L., McInerney, P., Godfrey, C. M., & Khalil, H. (2020). Updated methodological guidance for the conduct of scoping reviews. JBI Evidence Synthesis, 18(10), 2119–2126. https://doi.org/10.11124/JBIES-20-00167

Pini, B., Morris, D., & Mayes, R. (2016). Rural youth: Mobilities, marginalities and negotiations. In K. Nairn, P. Kraftl, & T. Skelton (Eds.), Space, place, and environment (pp. 463–480). Springer.

Poynton, C., & Lee, A. (Eds.). (2000). Culture & text: Discourse and methodology in social research and cultural studies. Allen & Unwin.

Quinn, F., Charteris, J., Adlington, R., Rizk, N., Fletcher, P., & Parkes, M. (2022). The potential of online technologies in meeting PLD needs of rural teachers. Asia-Pacific Journal of Teacher Education, 50(1), 1–15. https://doi.org/10.1080/1359866X.2020.1849538

Reid, J., Green, B., Cooper, M., Hastings, W., Lock, G., & White, S. (2010). Regenerating rural social space? Teacher education for rural-regional sustainability. Australian Journal of Education, 54(3), 262–276. https://doi.org/10.1177/000494411005400304

Roberts, P. (2014). Researching from the standpoint of the rural. In S. White & M. Corbett (Eds.), Doing educational research in rural settings. Methodological issues, international perspectives and practical solutions (pp. 135–148). Routledge.

Roberts, P., & Cuervo, H. (2015). What next for rural education? Australian and International Journal of Rural Education, 25(3), 1–8. https://doi.org/10.47381/aijre.v25i3.99

Roberts, P., & Fuqua, M. (Eds.). (2021). Ruraling education research: Connections between rurality and the disciplines of educational research. Springer.

Roberts, P., & Green, B. (2013). Researching rural places: On social justice and rural education. Qualitative Inquiry, 19(10), 765–774. https://doi.org/10.1177/1077800413503795

Roberts, P., & Guenther, J. (2021). Framing rural and remote: Key issues, debates, definitions, and positions in constructing rural and remote disadvantage. In P. Roberts & M. Fuqua (Eds.), Ruraling education research (pp. 13–27). Springer.

Sher, J. P., & Sher, K. R. (1994). Beyond the conventional wisdom: Rural development as if Australia’s rural people and communities really mattered. Journal of Research in Rural Education, 10(1), 2–43.

Shucksmith, M., & Brown, D. (2019). Framing rural studies in the global north. In M. Shucksmith & D. Brown (Eds.), Routledge international handbook of rural studies (pp. 1–26). Routledge.

Strijker, D., Bosworth, G., & Bouter, G. (2020). Research methods in rural studies: Qualitative, quantitative and mixed methods. Journal of Rural Studies, 78, 262–270. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jrurstud.2020.06.007

Tuck, E., McKenzie, M., & McCoy, K. (2014). Land education: Indigenous, post-colonial, and decolonizing perspectives on place and environmental education research. Environmental Education Research, 20(1), 1–23. https://doi.org/10.1080/13504622.2013.877708

Vass, G. (2015). Putting critical race theory to work in Australian education research: ‘We are with the garden hose here.’ The Australian Educational Researcher, 42(3), 371–394. https://doi.org/10.1007/s13384-014-0160-1

White, S., & Corbett, M. (2014). Introduction: Why put the ‘rural’ in research? In S. White & M. Corbett (Eds.), Doing educational research in rural settings. Methodological issues, international perspectives and practical solutions (pp. 1–4). Routledge.

Funding

Open Access funding enabled and organized by CAUL and its Member Institutions. While no specific funding was applicable for this project, the research was supported by ARC DECRA (2020–22) DE200100953.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Ethical approval

Ethics approval was not required for this analysis due to data being publicly available and no identifying information used in this analysis.

Additional information

Publisher's Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License, which permits use, sharing, adaptation, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if changes were made. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article's Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article's Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Roberts, P., Downes, N. & Reid, JA. Engaging rurality in Australian education research: addressing the field. Aust. Educ. Res. 51, 123–144 (2024). https://doi.org/10.1007/s13384-022-00587-4

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s13384-022-00587-4