Abstract

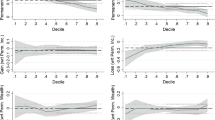

This paper investigates the effects of household indebtedness and housing wealth on consumption. To identify exogenous movements of housing wealth and leverage, we estimate housing supply elasticities for New Zealand urban centers. We construct synthetic panel series by using household survey data to estimate the marginal propensity to consume out of exogenous changes in housing wealth, while controlling for the household leverage ratio. Our empirical results show that, on average, the marginal propensity to consume out of housing wealth is about 3 cents out of one dollar. But it is larger, about 4 cents, in response to falling house wealth than to increasing housing wealth, about 2 cents. We further investigate the role of household indebtedness in accounting for the asymmetric effect. Our findings suggest that household leverage reinforces the housing wealth effect in a housing bust, but dampens the housing wealth effect in a boom.

Similar content being viewed by others

Notes

As we show in our brief literature review, housing wealth has been given numerous definitions depending on the identification technique employed in each study. As the main focus of this paper is exogenous variation in wealth coming from house price swings, we use the concepts “housing wealth” and “house price” effects on consumption interchangeably, unless otherwise specified.

See, (Carroll 2012), for a related discussion on the limitations of time-series data for studying wealth effects. Renowned exceptions include (Aron et al. 2012) and (Duca and Muellbauer 2014) who perform elaborated breaks between liquid and non-liquid wealth over time and (Lettau and Ludvigson 2004) who decompose between permanent and transitory innovations in wealth.

An alternative subjective measure of housing prices would be the reported prices by home-owners, as those prices would potentially reveal information on the perceptions of home-owners about their housing wealth and might point to different chosen levels of consumption out of it. As we show in Section 4, however, both measures are vulnerable to endogeneities. Consequently, we mainly use a measure of housing wealth based on exogenous house price elasticities and use the reported value within a robustness check.

The address of each household in the survey is reported at different levels of aggregation. The geographic aggregation of New Zealand is divided into 47062 mesh-blocks (MB), 2020 area units (AU), 65 territorial authorities (TA). To construct inflation-adjusted house prices, we use TA level of house price inflation reported by Real Estate Institute of New Zealand (REINZ). For some regressions we use TA dummies to control for regional fixed effects. For more information about geographic boundaries, visit the Statistics New Zealand web-page in https://www.stats.govt.nz/regional-data-and-maps/ For the dwellings rated in years prior to the survey date, we use REINZ data on house price inflation to ensure all house values are up to date. House prices are uprated at TA level.

This is done in two stages. First, we exclude any household which owns a house and receives rental income on another property. Second, we exclude houses with debt to house value ratio of higher than 0.8. Our empirical findings are not sensitive to this threshold.

For context, the variances of DTI, LTV and DSR are 0.032, 0.007, 0.002, respectively.

It should be noted that a caveat of cross-section analyses, including synthetic panels constructed from repeated cross-sections, is that it is not possible to disentangle age from cohort effects. Accordingly, we stress that our discussion on life-cycle behaviour rests on the assumption of no cohort effects. The restrictive assumptions on constructing the cohorts are discussed the next section.

Our results are robust to their inclusion.

The literature reports a strong negative association between home-ownership and residential mobility (Andrews and Sánchez 2011; Inchauste et al. 2018). A typical conjecture is that mobility is lower among home-owners than renters because the former face higher transaction costs of changing dwellings. Consequently they spend more time in their own residence to spread the costs over a longer time period.

In particular, the regions comprise of the following geographical territories: Auckland, Northland, Waikato, Bay of Plenty, Gisborne, Hawke’s Bay, Trananki, Manawatu-Wanganui, Wellington, Tasman District, Nelson City, Marlborough District, West Coast, Canterbury, Otago, and Southland.

See also (Baker 2018) who employs a similar identification strategy and discusses the issue more in detail with respect to the US.

The main alternative approach in the literature for estimating HSE is based on using an index of local regulations, and no such index is presently available for New Zealand. Estimates by (Lees 2019) provide indirect evidence that land-use regulation does matter.

“These numbers are based on the ”Subnational Population Estimates: At 30 June 2017 (provisional)” by Statistics New Zealand.

As discussed in the previous section of this paper, higher income expectations may drive both consumption and housing value of a household. On the other hand, unobservable factors negatively correlated with housing wealth, or measurement errors in house prices can lead to attenuation bias.

A similar approach using regression to the median for treating outliers in the related literature is followed by (Engelhardt 1996). In contrast to the results of the present paper, the results for the mean and the median regression in (Engelhardt 1996) differ substantially, implying a higher influence of outliers in the sample. For this reason, the author reports elasticities for both the mean and the median regression.

A further advantage of using micro data at a synthetic panel form is that they allow us to break the sample between age groups. The use of birth-cohorts in defining our synthetic panel allows us to do this, since birth-cohorts, not being a choice variable, remain exogenous, and thus can be used as a regressor.

Considering also the use of HSE as an instrument which is tested against confounding factors such as income expectations and productivity.

Results for leverage measures including DTI and DSR with respect to cohort construction generate similar patterns with the main findings of the paper and can be provided upon request.

From the statistical perspective the important advantage of this index over many other possible measures of housing supply is that it is exogenous to housing demand. It can therefore be used as an instrumental variable for housing supply allowing causal interpretations.

The values of index itself can be found in this appendix, and in the supplementary materials can be found here: https://www.dropbox.com/s/fdnze4pzixwx4ua/HousingSupplyIndex_NZ.xlsx?dl=0HousingSupplyIndex_NZ.xlsx, and here: https://www.dropbox.com/s/zqfqf71tstcd7tg/HousingSupplyIndex_NZ.csv?dl=0.csv). Some users may also want the distance of Meshblocks ids (as defined by 2001 New Zealand Statistics definitions) from each of the urban centres. These are given in https://www.dropbox.com/s/82gh0khiosmt2ui/DistToUrbC.txt?dl=0DistToUrbC.txt. They allow for easy mapping of the index to the level of meshblocks. For example, you might assign the index value for an urban centre to all meshblocks within 50km of that urban centre, doing this separately for each of the seventeen urban centres.

For comprehensive documentation on the index please contact either Mairead de Roiste, School of Geography, Environment & Earth Sciences, Victoria University of Wellington, mairead.deroiste@vuw.ac.nz. Or Robert Kirkby, School of Economics & Finance, Victoria University of Wellington, robertdkirkby@gmail.com

References

Aladangady, A. (2017). Housing wealth and consumption: Evidence from geographically-linked microdata. American Economic Review, 2017, 107 (11), 3415–46.

Altonji, JG, & Siow, A. (1987). Testing the response of consumption to income changes with (noisy) panel data. The Quarterly Journal of Economics, 1987, 102(2), 293–328.

Andersen, HY, Leth-Petersen, S, & et al. (2019). Housing Wealth Effects and Mortgage Borrowing: The Effect of Subjective Unanticipated Changes in Home Values on Home Equity Extraction in Denmark. Technical Report, CEPR Discussion Papers.

Andrews, D, & Sancheź, AC. (2011). The Evolution of Homeownership rates in selected OECD countries: Demographic and Public Policy Influences. OECD Journal: Economic Studies, (1), 1–37.

Angrisani, M., Hurd, M., Rohwdder, S. (2019). The Effect of Housing Wealth Losses on Spending in the Great Recession. Economic Inquiry, 57(2), 972–996.

Aron, J., Duca, J.V., Muellbauer, J., Murata, K., Murphy, A. (2012). Credit, housing collateral, and consumption: Evidence from Japan, the UK, and the US. Review of Income and Wealth, 58(3), 397–423.

Attanasio, OP, & Weber, G. (1994). The UK consumption boom of the late 1980s: aggregate implications of microeconomic evidence. The Economic Journal, 104(427), 1269–1302.

Attanasio, OP, Blow, L, Hamilton, R, & Leicester, A. (2009). Booms and busts: Consumption, house prices and expectations. Economica, 76(301), 20–50.

Baker, S. (2018). Debt and the response to household income shocks: validation and application of linked financial account data. Journal of Political Economics, 126 (4), 1504–1557.

Berger, D, Guerrieri, V, Lorenzoni, G, & Vavra, J. (2017). House prices and consumer spending. The Review of Economic Studies, 85(3), 1502–1542.

Berger, MC, & Blomquist, GC . (1992). Mobility and destination in migration decisions: the roles of earnings, quality of life, and housing prices. Journal of Housing Economics, 2(1), 37–59.

Bhatia, KB. (1987). Real estate assets and consumer spending. The Quarterly Journal of Economics, 102(2), 437–444.

Blundell, R., Pistaferri, L., Preston, I. (2008). Consumption inequality and partial insurance. American Economic Review, 98(5), 1887–1921.

Blundell, R., Browning, M., Costas, M., et al. (1994). A microeconometric model of intertemporal substitution and consumer demand. The Review of Economic Studies, 61(1), 57–80.

Bostic, R., Stuart, G., Painter, G. (2009). Housing wealth, financial wealth, and consumption: new evidence from micro data. Regional Science and Urban Economics, 39(1), 79–89.

Browning, M, Deaton, A, & Irish, M. (1985). A profitable approach to labor supply and commodity demands over the life-cycle. Econometrica, 53(3), 503–543.

Browning, M, Gørtz M, Leth-Petersen, S. (2013). Housing wealth and consumption: a micro panel study. The Economic Journal, 123(568), 401–428.

Bunn, P, & Rostom, M. (2014). Household debt and spending. Bank of England Working Paper Series, (554), 1.

Campbell, J.Y., & Cocco, J.F. (2007). How do house prices affect consumption? Evidence from micro data. Journal of monetary Economics, 54(3), 591–621.

Carroll, CD. (2012). Implications of wealth heterogeneity for macroeconomics, Technical Report, Johns Hopkins University Department of Economics, Baltimore, MD.

Carroll, CD, & Kimball, MS. (1996). On the concavity of the consumption function. Econometrica: Journal of the Econometric Society, 981–992.

Carroll, CD, & Kimball, MS. (2006). Precautionary Saving and Precautionary Wealth, Economics Working Paper Archive 530, The Johns Hopkins University, Department of Economics.

Carroll, C.D., Slacalek, J., Tokuoka, K. (2014). The distribution of wealth and the MPC: implications of new european data. American Economic Review, 104 (5), 107–111.

Carroll, C.D., Otsuka, M., Slacalek, J. (2011). How large are housing and financial wealth effects? A new approach. Journal of Money Credit and Banking, 43 (1), 55–79.

Case, K.E., Quigley, J.M., Shiller, R.J. (2005). Comparing wealth effects: the stock market versus the housing market. The B.E. Journal of Macroeconomics, 5(1).

Cerutti, E., Dagher, J., Dell’Ariccia, G. (2017). Housing finance and real-estate booms: a cross-country perspective. Journal of Housing Economics, (38), 1–13.

Christelis, D., Georgarakos, D., Jappelli, T. (2015). Wealth shocks, unemployment shocks and consumption in the wake of the Great Recession. Journal of Monetary Economics, 72, 21–41.

Christelis, D., Georgarakos, D., Jappelli, T., Pistaferri, L., Van Rooij, M. (2019). Asymmetric consumption effects of transitory income shocks. The Economic Journal, 129(622), 2322–2341.

Cloyne, J.ames., Huber, K., Ilzetzki, E., Kleven, H. (2019). The effect of house prices on household borrowing: a new approach. American Economic Review, 109(6), 2104–36.

Cooper, D, & Dynan, K. (2016). Wealth effects and macroeconomic dynamics. Journal of Economic Surveys, 30(1), 34–55.

Davidoff, T. (2016). Supply constraints are not valid instrumental variables for home prices because they are correlated with many demand factors. Critical Finance Review, 5(2), 177–206.

De Stefani, A. (2017). Waves of optimism: House price history, biased expectations and credit cycles. Edinburgh School of Economics, University of Edinburgh.

Deaton, A. (1985). Panel Data from Time Series of Cross-sections. Journal of Econometrics, 30(1), 109–126.

Demyanyk, Y, Hryshko, D, Luengo-Prado, MJ, & Sørensen, BE. (2017). The Rise and Fall of Consumption in the’00s: A Tangled Tale. Centre for Economic Policy Research.

Disney, R, Bridges, S, & Gathergood, J. (2010). House price shocks and household indebtedness in the United Kingdom. Economica, 77(307), 472–496.

Duca, J, & Muellbauer, J. (2014). Tobin LIVES: integrating evolving credit market architecture into flow-of-funds based macro-models. In B. Winkler, A. van Riet, & P. Bull (Eds.) A flow-of-funds perspective on the financial crisis. Palgrave Studies in Economics and Banking, (Vol. 2014 pp. 11–39). London: Palgrave Macmillan.

Dynan, K. (2012). Is a Household Debt Overhang Holding Back Consumption. Brookings Papers on Economic Activity, 43(1), 299–362.

Engelhardt, GV. (1996). House prices and home owner saving behavior. Regional Science and Urban Economics, (26), 313–336.

Fasianos, A, Lydon, R, & McIndoe-Calder, T. (2017). The balancing act: household indebtedness over the lifecycle. Central Bank of Ireland Quarterly Bulletin, 46.

Friedman, M. (1957). A theory of the consumption function,” in “NBER Chapter,” National Bureau of Economic Research.

Gan, J. (2010). Housing wealth and consumption growth: evidence from a large panel of households. The Review of Financial Studies, 23(6), 2229–2267.

Glaeser, EL, Gyourko, J, & Saiz, A. (2008). Housing supply and housing bubbles. Journal of Urban Economics, 64(2), 198–217.

Gourinchas, P-O, & Parker, JA. (2001). The empirical importance of precautionary saving. American Economic Review, 91(2), 406–412.

Guerrieri, L, & Iacoviello, M. (2017). Collateral Constraints and Macroeconomic Asymmetries. Journal of Monetary Economics, 90, 28–49.

Guren, AM, McKay, A, Nakamura, E, & Steinsson, J. (2018). Housing wealth effects: The long view. National Bureau of Economic Research.

Hilber, CA, & Vermeulen, W. (2015). The impact of supply constraints on house prices in England. The Economic Journal, 126(591), 358–405.

Huber, PJ. (1964). Robust estimation of a location parameter. The Annals of Mathematical Statistics, 35(1), 73–101.

Hviid, SJ, & Kuchler, A. (2017). Consumption and savings in a low interest-rate environment. Danmarks National Bank Working Papers, 116.

Iacoviello, M. (2005). House prices, borrowing constraints, and monetary policy in the business cycle. American Economic Review, 95(3), 739–764.

Inchauste, G, Karver, J, Kim, YS, & Jelil, MA. (2018). Living and Leaving: Housing, mobility and welfare in the european union world bank.

Jappelli, T, & Pistaferri, L. (2010). The consumption response to income changes. Annual Review of Economics, 2(1), 479–506.

Juster, F.T., Lupton, J.P., Smith, J.P., Stafford, F. (2006). The decline in household saving and the wealth effect. Review of Economics and Statistics, 88(1), 20–27.

Kaplan, G., Mitman, K., Violante, G.L. (2017). The Housing Boom and Bust: Model Meets Evidence. Working Paper 23694, National Bureau of Economic Research.

Kukk, M. (2016). How did household indebtedness hamper consumption during the recession? Evidence from micro data. Journal of Comparative Economics, 44(3), 764–786.

Le Blanc, JL, & Lydon, R. (2019). Indebtedness and spending: What happens when the music stops? Central Bank of Ireland Research Technical Paper, 14.

Lees, K. (2019). Quantifying the costs of land use regulation: evidence from New Zealand. New Zealand Economic Papers, 53(3), 245–269.

Lettau, M, & Ludvigson, SC. (2004). Understanding trend and cycle in asset values: reevaluating the wealth effect on consumption. American Economic Review, 94(1), 276–299.

Liebersohn, C. (2017). Housing demand, regional house prices and consumption, Working Paper, Ohio State University.

Mankiw, NG, & Zeldes, SP. (1991). The consumption of stockholders and nonstockholders. Journal of Financial Economics, 29(1), 97–112.

Mian, A, & Sufi, A. (2011). House prices, home equity-based borrowing, and the US household leverage crisis. American Economic Review, 101(5), 2132–56.

Mian, A, & Sufi, A. (2014). What explains the 2007–2009 drop in employment? Econometrica, 82(6), 2197–2223.

Mian, A., Rao, K., Sufi, A. (2013). Household balance sheets, consumption, and the economic slump. Quarterly Journal of Economics, 128(4), 1687–1726.

Modigliani, F, & Brumberg, R. (1954). Utility analysis and the consumption function: an interpretation of cross-section data. Post Keynesian Economics, (6), 388–436.

Muellbauer, J, & Murphy, A. (1990). Is the UK balance of payments sustainable?. Economic Policy, 5(11), 347–396.

Muellbauer, J, & Murphy, A. (2008). Housing markets and the economy: the assessment, (Vol. 24.

Murphy, L. (2011). The global financial crisis and the Australian and New Zealand housing markets. Journal of Housing and the Built Environment, 26(3), 335.

Paiella, M, & Pistaferri, L. (2017). Decomposing the wealth effect on consumption. Review of Economics and Statistics, 99(4), 710–721.

Price, F., Beckers, B., Cava, G.L. (2019). The effect of mortgage debt on consumer spending: evidence from household-level data. Technical Report, Reserve Bank of Australia.

Rousseeuw, PJ, & Zomeren, BCV. (1990). Unmasking multivariate outliers and leverage points. Journal of the American Statistical Association, 85(411), 633–639.

Saiz, A. (2010). The geographic determinants of housing supply. Quarterly Journal of Economics, 125(3), 1253–1296.

Sinai, T, & Souleles, NS. (2005). Owner-occupied housing as a hedge against rent risk. The Quarterly Journal of Economics, 120(2), 763–789.

Skinner, J. (1989). Housing wealth and aggregate saving. Regional Science and Urban Economics, 19(2), 305–324.

Skinner, JS. (1996). Is housing wealth a sideshow? In D. Wise (Ed.) Advances in the Economics of Aging (pp. 241–268). Chicago: University of Chicago Press.

Smith, M. (2010). What do we know about equity withdrawal by households in New Zealand? In S.J. Smith, & B.A. Searle (Eds.) The Blackwell Companion to the Economics of Housing.

Tan, A, & Voss, G. (2003). Consumption and wealth in Australia. Economic Record, 79(244), 39–56.

Verbeek, M. (2008). Pseudo-panels and repeated cross-sections. In The econometrics of panel data (pp. 369–383). Berlin: Springer.

Verbeek, M, & Nijman, T. (1992). Can Cohort Data be treated as Genuine Panel data? Empirical Economics, 17, 9–23.

Windsor, Ca, Jääskelä, JP, & Finlay, R. (2015). Housing wealth effects: evidence from an Australian panel. Economica, 82(327), 552–577.

Yao, J., Fagereng, A., & Natvik, G. (2015). Housing, debt and the marginal propensity to consume. Working paper, Johns Hopkins University.

Zhu, B., Li, L., Downs, D.H., Sebastian, S. (2019). New evidence on housing wealth and consumption channels. The Journal of Real Estate Finance and Economics, 58(1), 51–79.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Additional information

Publisher’s Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

The authors would like to thank Dimitris Christelis, Ashley Dunstan, James Graham, Dean Hyslop, Christie Smith, Sofia Vale, Albert Saiz, Dennis Wesselbaum, as well as the editor, C.F. Sirmans, and an anonymous referee for their valuable comments. We also thank seminar participates at the Reserve Bank of New Zealand, Otago University, and New Zealand Treasury for helpful feedback. We thank Jiten Patel for his research assistance work as a Summer Research Scholar. The first draft of this paper was written while Fasianos was visiting RBNZ, whose hospitality is gratefully acknowledged. The views expressed in the paper do not necessarily reflect those of the Reserve Bank of New Zealand, nor the Hellenic Ministry of Finance. Access to the data used in this study was provided by Statistics New Zealand under conditions designed to give effect to the security and confidentiality provisions of the Statistics Act 1975. The results presented in this study are the work of the authors, not Statistics NZ.

Appendices

Appendix A: Literature Table

Appendix B: The New Zealand Household Expenditure Survey

Appendix C: Additional Figures and Tables

Appendix D: Geographical Housing Supply Elasticity Index for New Zealand

Following the methods of (Saiz 2010)

House prices in New Zealand rose rapidly in in the 2010s. To assess whether these rises imply a housing boom and bust or reflect fundamental changes in supply and demand we need to be able to measure housing supply adequately. The number of new houses, or of houses-per-inhabitant capture the interplay of supply and demand, not supply directly. We introduce an index based on geographical constraints for New Zealand that provides a direct measure of (potential) housing supply.Footnote 23

This Geographical-Contraints Housing Supply Index closely follows that introduced by (Saiz 2010) for the United States, who also demostrates its empirical usefulness. The measure is calculated at the level of cities as the fraction of land within a 50km radius that is unavailable for use due to being either ocean, wetlands, or too steep.

This appendix provides the values of the index for the seventeen largest urban areas in New Zealand. We also provide the corresponding regions and mesh-blocks, to make the index easy to combine with data from other sources. The remainder of this appendix briefly details the construction of the index. We give precise definitions, listing all data sources, and provide process diagrams for the GIS (Geographical Information Systems) calculations involved. We discuss and provide justifications for any decisions that had to be made as part of the construction of the index.Footnote 24

Summary of Methodology

We briefly describe the details of the methodology employed to create a measure of the total land unavailable for residential development in New Zealand following (Saiz 2010).Footnote 25 Saiz’s study explores land unavailability for 95 MSAs (Metropolitan Statistical Areas) in the United States. Saiz identified unavailable land using slopes of greater than 15%, land area (as indicated by a contour map), unsuitable land cover (not wetlands, lakes or rivers) and city centres.

Our study uses ESRI’s ArcGIS 10.3.1 to replicate Saiz’s methods using measures of New Zealand’s slope, land cover, coastline and city centres. Where possible datasets close to 2001 were used to replicate Saiz’s study. The resulting geographic areas are represented in Figure 3.

City centres: Saiz used the geographic city centres of 95 MSAs (Metropolitan Statistical Areas). These centres have populations “⋯ hellip;over 500,000 in the 2000 Census for which I also have regulation data⋯hellip;” (Saiz, 2010, p1257). He does not state how these centres are determined. Our study uses the 17 main urban areas of New Zealand as identified by Statistics New Zealand based on a 2001 population. These urban areas vary in population from 1,129,700 (Auckland) to 27,300 (Blenheim). City centres in New Zealand were created using current town halls and district council buildings using with Google Maps.

City centre radius: Saiz defines a radius of 50km to calculate the amount of land unavailable for residential development using census block groups (roughly equivalent to mesh-blocks) for slope and using census tracts (roughly equivalent to Area Units) for land cover. Distance from the city centre to each meshblock centroid in New Zealand was calculated and a maximum value of 50km was used to determine the mesh-blocks within the radius. For consistency across datasets, only mesh blocks were used for analysis in NZ.

Slope: Saiz identifies slope as a primary characteristic of land unavailable for development. In particular, land with a slope of greater than 15% is “⋯hellip;severely constrained for residential construction” due to “Architectural development guidelines...” (Saiz, 2010 p1256). Saiz calculated slope within a 50km radius from city centres using a 90m Digital Elevation Model (DEM) from the United States Geological Survey (USGS). To replicate Saiz’s work, the University of Otago’s 15m DEMs were re-sampled to 90m resolution. Slope was measured as ’PERCENT_RISE’ and areas of greater than 15% were identified.

Land cover: Saiz identifies inland waterbodies and wetlands as ‘undevelopable area’. New Zealand land cover was sourced from the New Zealand Land Cover Database 2 (LCDB 2) for summer 2001/2002. There is no strict definition of wetlands from LCDB 2 and relevant vegetation classes were combined. Unsuitable land cover areas were identified as ’Lake and Pond’, ’River’, ’Estuarine Open Water’, ’Herbaceous Freshwater Vegetation’, ’Herbaceous Saline Vegetation’, ’Flaxland’ and ’Mangrove’.

Coastlines: Saiz used digital contour maps to delineate areas made unavailable by oceans and the Great Lakes. The data source was not provided. New Zealand’s coastlines and islands were sourced from the Land Information New Zealand (LINZ) data service (2015). The data comprises coastline and island outlines. The amount of area lost to oceans within a 50km radius was found using the city centres and removing overlapping wetland areas from the land cover criteria.

Combining relevant data: Using the exclusion criteria of unsuitable slope (over 15%), unsuitable land (wetlands, rivers or lakes) and ocean within 50km of the city centre, Saiz identifies undevelopable areas. The three criteria were combined for each of the 17 urban areas in New Zealand and the fraction of land unavailable for development is provided in Table 12.

Appendix E: Additional Robustness Checks

Rights and permissions

About this article

Cite this article

de Roiste, M., Fasianos, A., Kirkby, R. et al. Are Housing Wealth Effects Asymmetric in Booms and Busts?. J Real Estate Finan Econ 62, 578–628 (2021). https://doi.org/10.1007/s11146-020-09757-6

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s11146-020-09757-6