Abstract

Cryoablation is safe and effective for the treatment of atrial fibrillation (AF) in controlled clinical trials, but contemporary real-world usage and outcomes are limited. The Report of the Spanish Cryoballoon Ablation Registry (RECABA) was designed to evaluate acute and 12-month outcomes of cryoballoon ablation for the treatment of AF in Spain. Patients from 27 Spanish centers were prospectively enrolled. Patients were treated with cryoballoon ablation and managed according to standard of care protocols at each center. The primary endpoint was ≥ 30 s freedom from AF at 12-month after a 3-month blanking period. Secondary endpoints included a description of patient characteristics, cryoablation procedural strategy and safety, and predictors of efficacy. In total, 1742 patients (71.4% PAF, 68.8% male, mean age 58.02 ± 10.40 years, 76.1% overweight or obese, CHA2DS2-VASc index 1.40 ± 1.28) were enrolled. Patients received 7.2 ± 2.67 cryo-applications. PV potentials could be detected in 61% of the PVs during ablation, with a mean time to block of 52.9 ± 37.02 s. Acute PVI was observed in 97% of PVs with 75.8% isolated with the first cryo-application. Mean procedural time was 113 ± 41 min. Acute complications occurred in 4.4% of the cases. With follow-up in 1628 patients, AF-free survival was 78.5% (PAF: 80.6% vs PersAF 73.3%; p < 0.001). Left atrium enlargement, female sex, non-PAF, and early recurrence were independent predictors of AF recurrence (p < 0.05). RECABA provides detailed insight into current dosing practices and demonstrates cryoablation is safe and effective in real-world use.

ClinicalTrials.gov number: NCT02785991.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

Cryoballoon ablation (CBA) is a well-established technique for the treatment of atrial fibrillation (AF), that has been demonstrated to achieve similar safety and efficacy as radiofrequency ablation (RFA) with shorter procedure times1. Previous studies have suggested a benefit to intervention with ablation before drug failure, because a shorter “diagnosis-to-ablation” time is associated with better outcomes2,3.

While the safety and efficacy of AF ablation has been established, it was only until recently that outcomes of AF ablation were examined within large, prospectively enrolled cohorts of patients with AF. The recent report from the Cryo AF Global Registry described primary outcomes of cryoablation used according to local practice around the world4. Country specific evaluations such as the GWTG-AFIB study, the FREEZE Cohort, and the 1STOP registry describe outcomes of cryoablation in the USA, Germany, and Italy, which have had many years of experience with the cryoablation catheter5,6,7. Uniquely, a recent report from Miyazaki et al. described the first safety experience with cryoablation in Japan8. A comprehensive examination of modern cryoablation outcomes in an early, pan-country experience with cryoballoon ablation has yet to be reported.

The Spanish Catheter Ablation Registry is published annually as the official report of the Spanish Society of Cardiology Working Group on Electrophysiology and reflects general activity in Spanish electrophysiology units but does not describe AF ablation procedures in detail; therefore, patient selection, procedural techniques, and outcomes in real-world use in Spain have not been reported9. The Spanish Registry of Cryoballoon Ablation (RECABA) prospective multicenter observational study aimed to comprehensively evaluate daily clinical practice and the current state of cryoballoon procedures in Spain.

Methods

Study design and population

The Registro Español de CrioAblación con BAlón (RECABA; NCT02785991) is an observational, prospective, national, multicenter (Supplementary Material Online S1, Table S1) study of patients undergoing CBA for AF in Spanish centers with experience in the technique (at least ten procedures per year). Patients were enrolled between September 2016 and January 2019. For inclusion in the study, patients were required to (1) be older than 18 years of age, (2) be eligible for CBA for AF, (3) have a life expectancy greater than 1 year, and (4) sign the informed consent. Patients with both first and repeat procedures were enrolled. AF was classified as paroxysmal (PAF) or persistent atrial fibrillation (PerAF) according to the current ESC guidelines10. Clinical data were collected at the baseline procedure and at the annual follow-up by the coordinator responsible for each center through an electronic data collection system for clinical trials (eCRF). Data collection, management and quality control are detailed in Supplementary Material Online (S2). Figure 1 shows a visual representation of the protocol and its timeline.

Ethics Committee approval was obtained according to local legislation. The study was conducted in compliance with the most recent version of the Declaration of Helsinki, Spanish laws and regulations (Royal Decree 1090/2015, Royal Decree 1616/2009, Order SAS/3470/2009 of 16 December). This observational study did not require authorization by the Spanish Agency of Medicines and Medical Devices (AEMPS), as stipulated in Royal Decrees 1090/2015 and 1616/2009, since it is a clinical investigation with CE marked medical devices used in accordance with the clinical purpose of the device. The study was assessed and approved by the IRB, Comité Ético de Investigación Clínica de Euskadi (CEIC-E) on May 9, 2016, and by the Ethical Committee of Hospital de Mar, Comité Ético de Investigación Clínica del Consorci Mar Parc de Salut de Barcelona (CEIC-Parc De Salut Mar) on June 21, 2016. All patients signed informed consent before inclusion in the registry.

Objective and endpoints

The main objective of the RECABA was to report standard clinical practice for PVI using CBA in Spanish hospitals. Standard clinical practice was evaluated by assessing patient characteristics, procedural and CBA techniques, procedure-related complications, the long-term follow-up strategy and efficacy across Spanish centers. The primary endpoint of the study was AF free survival at the 12-month follow-up. Secondary endpoints included the following: (1) a description of baseline characteristics of subjects who underwent CBA, (2) the acute efficacy, safety (the rate of all procedure-related adverse events), and efficiency of the procedure (e.g. electrical PVI, PV potential monitoring, cryoapplications analysis, related complications, and procedural related times), (3) description of the dosing strategies utilized, and (4) identification of the factors that predicted AF recurrence during follow-up.

Cryoballoon ablation procedure

General pre-ablation management and the CBA procedure were done in accordance with each center’s standard protocol for pre-ablation examination, anesthesia and sedation, auxiliary technology for transseptal puncture, anatomical assessment, and phrenic nerve monitoring during right-sided ablation. Nevertheless, the CBA procedure was similar in all hospitals as cryoballoon-over-the-wire techniques were required to follow the internationally accepted techniques described in detail in recent publications and in the Supplementary Material Online (S3)11,12. Of note, the following cryo-dosing parameters followed the usual practice of each hospital including duration of cryoapplications, post-ablation waiting time, and post ablation acute PVI adenosine testing. Initially, an extra application of cryothermia (bonus application) was carried out after the application that had blocked the pulmonary vein. In recent years, after the publication of studies showing that this extra application is not necessary, the tendency is to avoid it, since it does not provide clinical benefit and could be related to an increase in complications13. In this Registry, the bonus/non bonus freeze strategy also followed the usual practice of each hospital.

Post-ablation management and follow-up

Oral anticoagulation (OAC) and anti-arrhythmic drug (AAD) management were done in accordance with each center’s standard protocol and at the discretion of the cardiologist. Patients could continue taking AAD in the absence of recurrences. Patients were followed with outpatient visits using 24 h to 30-day Holter monitoring systems over the 12-month follow-up. Arrhythmia recurrence could also be monitored via electrograms registered in patients with an implanted device prior to (but not after) enrollment in the study. Patients were also instructed to perform an ECG when they present with symptoms. AF recurrence was defined as any AF episode that lasted longer than 30-s accordingly documented (on ECG, Holter monitor, event recording systems or implantable devices). A 3-month blanking period was established, during which detected AF episodes were excluded from the primary endpoint.

Statistical analysis

Quantitative variables are expressed as mean, median, standard deviation and interquartile range as appropriate. Differences in quantitative variables were evaluated through the student t-test for independent samples (or analysis of variance depending on the number of groups compared) and between paired variables through the student t-test for related samples or the analysis of variance for repeated measures. Categorical data were compared with the chi-square test or Fisher’s exact test, depending on the number of categories. The probability of recurrence was predicted using a logistic regression, and a survival analysis predicted the most likely time of recurrence. Univariate models considering each potential predictor were estimated. Subsequently, a multivariate model considering predictors from the baseline visit and procedural characteristics were estimated. An overall multivariate model including significant variables was estimated with non-significant variables as covariates. Time to recurrence was studied using Kaplan–Meier estimates and categorical predictive covariates were included as grouping variables and compared using the log-rank statistic. The Cox-proportional hazard regression method was used to estimate the conditional hazard rate. In order to study AAD use retention at follow-up visits, a logistic loglinear model was estimated, including AF type, AAD use after cryoablation procedure and AF recurrence. Effect confidence intervals and model standardized residuals were obtained. Chi-square for independence was used as test statistic for independence. All analyses were carried out using IBM SPSS v26.0 software. A nominal 5% significance level was assumed in all analysis and adjustments for multiple comparisons were completed when needed.

Results

Study population

A total of 1742 patients eligible for CBA for the treatment of paroxysmal (1238; 71.1%) or persistent (504; 28.9%) AF were prospectively included from 27 Spanish Centers. The mean number of patients included per center was 64.5 ± 53.21, (13 centers enrolled less than 50 patients, 9 enrolled between 51 and 100, 3 between 101 and 150 and 2 enrolled more than 150 patients). All but one enrolled patient (who opted out of the procedure after singing informed consent) underwent a CBA. Of all procedures, 1665 (96.6%) were first CBA procedure and 77 (4.4%) were repeat ablation procedures.

Clinical characteristics of the study population are shown in Table 1. Most patients were male (68.8% versus 31.2%; p < 0.001), under 65 years old (70.7%), and were overweight or obese (76.1%). Only 52 patients (3%) were older than 75 years. One patient was younger than 20 years and 4 patients were older than 80 years of age. The most frequently observed cardiovascular risk factors were hypertension (46.3%) and dyslipidemia (34.7%). The population presented a low embolic risk overall (mean CHA2DS2-VASc index 1.40 ± 1.28), but CHA2DS2-VASc was ≥ 2 in 39.8% of the cohort. Only 18.9% of patients had structural heart disease (most frequently tachycardia-related cardiomyopathy and coronary artery disease) and left ventricular ejection fraction was preserved in most patients (≥ 50% in nearly 90% of the patients). LA was enlarged (LA > 40 mm or area > 20 cm2) in over half of the patients (most frequently mild). Oral anticoagulation (most frequently direct anticoagulation drugs) and AADs were taken at baseline in 75.5% of patients. In 148 patients (8.5%) CBA was used as a first-line treatment. Patients had PAF with a mean time since diagnosis of more than 1 year in 85.6% of cases.

Procedural characteristics

Procedure characteristics were analyzed from a total of 1741 CBA procedures (Table 2). In nearly 65% of patients pre-procedural imaging was performed to assess PV anatomy. Most patients (1316 patients; 76.5%) had 4 independent PVs. Only 15% of procedures were performed under general anesthesia. The 28 mm Arctic Front Advance cryo-balloon was used in 93.8% of the cases. A bonus freeze strategy was systematically employed in 553 procedures (33.7%) and was never employed in 679 (41.4%) procedures. In 407 procedures (24.8%), a bonus application was administered depending on the perception of the quality of the previous application by the operator. Procedure times (cryotherapy, left atrium, total procedure, and X-ray exposure times) are shown in Table 3. Mean number of applications and mean total cryotherapy time was 7.2 ± 2.67 and 21.1 ± 7.80 min per patient, respectively. Patients treated with a no-bonus strategy received significantly fewer (but longer duration) applications, had a shorter time to effect (TTE), and received significantly shorter cryotherapy, LA and fluoroscopy exposure times (p < 0.001); however, total procedure time did not reach statistical significance between no-bonus and bonus strategies (p = 0.07). Figure 2 shows the distribution of total cryotherapy (A) and procedural times (B).

Acute procedural outcomes and applications analysis

A total of 12,495 cryoapplications applied to 6715 PVs (277 left and 30 right common trunks) were performed, for a mean of 1.8 applications per vein. At the end of the procedure 97% of PV were isolated, of which 75.8% were isolated with the first cryoapplication. In 13% of the cases patients received only one application per vein for PVI (4 applications per intervention). The rest of the patients (86.2%) received more than one application in any of the locations. Global and per vein data analysis are summarized in Table 4. Potentials inside the PV could be monitored during ablation in 61% of PVs with a mean TTE of 52.9 ± 37.02 s. Figure 2 shows the histograms of the distribution of TTE (C), temperature at PVI (D) and the minimal temperature reached (E). The most frequent cryoapplications duration was 180 or 240 s (F).

Periprocedural-related complications

Periprocedural and procedural-related complications occurred in 120 patients (6.9%). Acute intraprocedural complications were reported in 77 patients (4.4%). The most frequent adverse event observed was phrenic nerve injury (49 patients; 3%), of which 36 (73.5%) recovered immediately. All but three patients had recovered normal phrenic motility at time of study exit. Other complications occurred in less than 1% of the patients and are summarized in Table 5. Notably, 8 (0.45%) patients developed cardiac tamponade, 16 (0.97%) vascular damage (1 arteriovenous fistula requiring surgery), 12 (0.68%) transient ST elevation events, and 9 (2 intraprocedural and 7 in the 30-days post ablation) patients had a cerebral stroke or transitory ischemic attack (TIA). In total, major adverse cardiovascular effects (MACE; including stroke/TIA, ST-segment elevation, and cardiac tamponade) occurred in 29 (1.6%) patients. No intraprocedural deaths occurred.

Five deaths (0.29%) occurred during follow-up, 2 (0.12%) of which occurred during the first 30 days after the procedure. One death within 30 days was due to a traumatic cerebral hemorrhage and the other due to a mesenteric embolism (the patient was not taking the correct anticoagulant dosage). Three patients died between 140 and 308 days post procedure, one patient died as a result of lung neoplasia, one due to a complication after a left atrial appendage occlusion, and one due to an asystole documented bay emergency service (no more data were collected). In 1 patient an atrio-esophageal fistula occurred during the first month after ablation. The patient presented with global sepsis. This complication was resolved surgically, but the patient suffered serious neurologic damage. No clinical PV stenoses were reported during follow-up. At the end of the study, 95.8% of the adverse events were resolved.

Follow-up and AF recurrence predictors

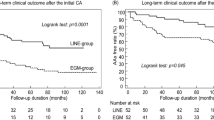

Of the 1742 patients enrolled in the RECABA, 1628 (93.4%) completed 12-month follow-up (6.54% lost to follow-up rate, mostly due to restrictions caused by the Covid-19 pandemic) with a median follow-up of 375 (IQR 342–415) days since the index procedure. Arrhythmic event monitoring was conducted with electrocardiography (48.6%), 24-h Holter monitoring (39.9%), 72-h Holter monitoring (3.6%), implantable continuous loop recorder (2%) and non-implantable continuous recorders (3.4%). The 12-month Kaplan–Meier estimate of freedom from AF recurrence after the blanking period was 78.5% (95% CI 76.3–80.7%; Fig. 3A). The 12-month estimate of freedom from a ≥ 30 s recurrence of AF in patients with PAF was superior to those with PerAF (80.6% CI 78.1–81.1% vs 73.3% CI 68.8–77.8% respectively; p < 0.001; Fig. 3B).

Baseline patient characteristics and procedural variables were analyzed to identify predictors of AF recurrence (Table 6). Univariate analyses identified the following baseline characteristics predicted AF recurrence: ≥ 65 years of age, female gender, non-PAF, CHA2DS2-VASc ≥ 2, no physical activity, structural heart disease, LVEF ≤ 50%, and LA enlargement. The following predictors were found close to the limit of significance: using a bonus strategy (p = 0.098; 95% CI 0.96–1.55) and duration of AF history > 1 year (p = 0.098; 95% CI 0.95–1.83). A multivariate model identified the following independent predictors of AF recurrence: non-PAF (OR = 1.70, p < 0.001, 95% CI 1.31–2.20), LA enlargement (OR = 1.35, p = 0.017, 95% CI 1.05–1.73), and female gender (OR = 1.33, p = 0.039, 95% CI 1.01–1.76). In total, 276 patients (17%) had AF recurrence during the blanking period, and AF recurrence during the blanking period was a significant post-procedural predictor of arrhythmia recurrence (HR = 5.98, p < 0.001, 95% CI 4.96–7.20; HR = 6.06, p < 0.001, 95% CI 4.93–7.46 for univariate and multivariate analysis respectively). Figure 4 shows Kaplan–Meier free survival curves for highlighted independent and potential predictors AF recurrence.

The AF recurrence rate did not differ based on center volume in this study (p = ns) (Fig. 5). However, procedure time, fluoroscopy time, cryoablation time, and percentage of isolated veins was improved in more experienced centers, and a bonus cryoapplication strategy was used more often in experienced centers (all p < 0.001). The adverse event rate was not different between centers grouped by experience (p = 0.1) (“S4”, Table S2, “Supplementary Material Online”).

AF recurrence and no-recurrence at 12-months of follow-up (absolute number of patients) by center experience. Centers were divided into four quartiles of expertise with a fixed range of 55 patients in each quartile, increasing in the level of experience. There was not statistical difference regarding either overall recurrence at 12-month follow-up or the rate of adverse events. Procedure characteristics were different between quartiles (Table S2).

Medications during follow-up

After CBA, 89.8% of patients were discharged after 1 day or less (median time to discharge 1 day; mean 1.25 ± 2.01 days). Although there were no protocol requirements for AAD usage, medication data were collected. At time of discharge, 1131 patients (65%) were taking AAD, most frequently Class Ic agents (690 patients; 61.2%) and amiodarone (333 patients; 29.5%). All patients were taking an OAC agent at discharge (1270; 72.9% patients taking direct OAC).

Of the 1628 patients who completed follow-up, 1038 were on AADs (63.8%), with a similar proportion in PAF (63%) and PerAF (65.8%). The percentage of patients free of AF recurrence on AADs at 12-month follow-up was also similar between PAF and PerAF groups (29.5% vs 28.9 respectively, p = ns). Patients discharged under AAD treatment were more likely to continue AADs at the end of follow-up, irrespective of AF recurrence (29% versus 12% in the PAF group; p = 0.002). Figure 6 displays the cohort according to type of AF, AAD at discharge, recurrences and AAD at the final follow-up.

Discussion

The RECABA registry is the largest cryoballoon registry in Spain and reflects the standard clinical practice and clinical characteristics of patients treated by CBA for PVI in Spanish hospitals. AF is the most frequently ablated arrhythmia in Spain (27.8% of all arrhythmias), and last year, 42% of these procedures were performed with cryoballoon9. The results of RECABA demonstrated acute and subacute complications associated with real-world usage of CBA for treatment of AF were rare (6.9%), and cryoablation was effective with 79% freedom from AF at 12-month when used according to standard clinical practice in 27 unique centers in Spain.

Tailored and efficient cryoballoon ablation procedure

Patients in RECABA were mostly young, overweight adult males who presented with PAF without structural heart disease and are consistent with baseline characteristics of patients enrolled in other European, multicenter registries7,8,14. The cryoablation procedure was frequently performed under superficial sedation, which has been reported to result in shorter procedure times without compromising AF recurrences or complication rates15. During recent years, cryothermal dosing protocols have also evolved towards shorter application times based on per-PV TTE with or without bonus applications, and have resulted in more efficient procedure times than fixed cryoapplication times16,17,18. This trend was also observed in RECABA in which two thirds of the centers systematically used dosing protocols without bonus applications that led to significantly fewer applications per patient and shorter procedure, cryotherapy, and LA times. Centers with more experience applied the bonus strategy to a greater extent; although, there is no clear explanation for this observation. It is possible these centers perceived a greater need for applications as they treated more patients with PerAF; thus, it is important to attempt PV potential monitoring during ablation to tailor dosing to each PV. In the RECABA registry, PV potentials could be seen during ablation in 61% of the veins and more often in left PVs. These results are similar to contemporary reports, and rates have improved with the introduction of new generations of cryoballoon16,17,18,19. General procedure times in the RECABA registry, such as cryotherapy, LA and x-ray exposure times were comparable to those obtained in other studies, and they were significantly reduced in non-bonus protocols7,9,14,16. These data corroborate a trend toward simplifying and maximizing efficiency of AF ablation procedures.

Antiarrhythmic drugs on long-term outcomes

There are mixed reports on the influence of short-term use of AADs on long-term outcomes after AF ablation20,21,22. The European survey of AF ablation practice that included 1300 patients from 72 European institutions found that among a patient population that was more than two-thirds PAF, 65% of patients were discharged post-ablation on an antiarrhythmic medication and 49% remained on antiarrhythmic medication at 12 months23. The RECABA study observed similar rates of AAD usage after discharge. Although further randomized data are required, patients discharged on AADs were more likely to continue AAD use throughout study follow-up even in the absence of arrhythmia recurrence. The reasons for this may range from a perception of added efficacy of the AAD or its additional effect on the ablation, but more probably it is due to the nature of a registry and lack of strict control in the follow-up. In the group of PerAF, however, the differences were non-significant (Fig. 6).

Predictors of outcomes after cryoablation

Independent predictors for AF recurrence were female sex, non-PAF, LA enlargement, and early recurrence in blanking period. Non-PAF and LA enlargement are a well-established predictors of AF recurrence24. In the recent CRYO4PERSISTENT AF Trial25, a controlled multicenter study, a single CBA for treatment of PerAF demonstrated 61% success at 12 months and improved quality of life which is in accordance with the data of the current study. A sub-analysis of the Fire and Ice Trial showed that female sex was associated with an almost 40% increase in the risk of AF recurrence and cardiovascular rehospitalization after PV isolation26. In the RECABA study we found early recurrence in blanking period increased the risk for late AF recurrence sixfold. Lack of recurrence in the blanking period, however, had less predictive power in the PerAF group. In accordance with this finding, early AF recurrence in blanking period (classically considered as non-valuable and unrelated with late AF recurrence, especially in radiofrequency PV ablations) has been found as a strong predictor of long-term AF recurrence in several recent studies27, especially when it occurs in the second or third month after ablation. These data align with some authors suggestion that recurrences during the blanking period should be redefined28.

Interestingly, the independent predictors of AF recurrence within the RECABA registry were in general alignment with the findings of large-randomized trials, as well as the safety and efficacy data. Consequently, the RECABA results demonstrate the value of using real-world registries to further validate study findings from randomized controlled trials.

Study limitations

The RECABA registry was a multicenter prospective observational registry; therefore, acknowledged limitations include potential bias in patient selection, varied patient management, and the lack of a control group. Nevertheless, possible biases are mitigated by the fact that data were collected prospectively, and research endpoints were pre-specified. As per nature of this project, a standardized-cryoballoon dosing protocol was not implemented. Few patients were implanted with an internal loop-recorder; therefore, asymptomatic episodes may have occurred unnoticed, and our success rate may have been over-estimated. Complications that occurred during the ablation procedure may be registered adequately in a registry, but the voluntary nature of data provision may have led to underreporting of procedural complications after the ablation. No recommendations were provided to the participating centers in terms of pharmacological treatment following CBA. Thus, the exact temporal sequence of AAD management could not be established, and it is unknown whether AADs were simply continued after the blanking period as per center practice. Multivariate predictive models could be affected by variables not considered in the particular model (residual confounding), since only statistically significant predictors have been considered. Being an observational study, no effort has been made to control for covariates by sampling design.

Despite limitations, this prospective research may provide a representative analysis of the real-world outcomes of CBA in a broad cohort of patients with AF in a large number of centers with different levels of experience.

Conclusions

Cryoablation was effective and safe when used according to standard clinical practice during the early cryoballoon ablation experience at 27 unique centers in Spain. LA enlargement, non-PAF, female sex and early AF recurrence in the first 3 months independently predicted late AF recurrence.

Perspectives

Clinical competencies

-

Cryoablation for the treatment of AF performed according to standard clinical practice in 27 centers was safe and effective.

-

Cryoballoon ablation is commonly delivered with a tailored, efficient approach.

-

Female sex, non-PAF, LA enlargement, and early recurrence in blanking period predicted recurrence during 12-month follow-up.

Translational outlook

Cryoballoon ablation is used to treat a broad group of patients with atrial fibrillation and results in consistent outcomes.

Data availability

The data that support the findings of this study are available from the corresponding author, A.F., with permission of the Medtronic team upon reasonable request.

Abbreviations

- AF:

-

Atrial fibrillation

- PV:

-

Pulmonary vein

- PVI:

-

Pulmonary vein isolation

- AAD:

-

Antiarrhythmic drugs

- CBA:

-

Cryoballoon ablation

- RFA:

-

Radiofrequency ablation

- PAF:

-

Paroxysmal atrial fibrillation

- PerAF:

-

Persistent atrial fibrillation

- OAC:

-

Oral anticoagulation agents

- TIA:

-

Transient ischemic attack

- MACE:

-

Major adverse cardiovascular event

References

Kuck, K. H. et al. Cryoballoon or radiofrequency ablation for paroxysmal atrial fibrillation. N. Engl. J. Med. 374, 2235–2245 (2016).

Andrade, J. G. et al. Cryoablation or drug therapy for initial treatment of atrial fibrillation. N. Engl. J. Med. 384, 305–315 (2020).

Wazni, O. M. et al. Cryoballoon ablation as initial therapy for atrial fibrillation. N. Engl. J. Med. 384, 316–324 (2021).

Chun, K. R. J. et al. Safety and efficacy of cryoballoon ablation for the treatment of paroxysmal and persistent AF in a real-world global setting: Results from the Cryo AF Global Registry. J. Arrhythmia. 37, 356–3673 (2021).

Friedman, D. J. et al. Procedure characteristics and outcomes of atrial fibrillation ablation procedures using cryoballoon versus radiofrequency ablation: A report from the GWTG-AFIB registry. J. Cardiovasc. Electrophysiol. 32(2), 248–259. https://doi.org/10.1111/jce.14858 (2021) (Epub 2021 Jan 6 PMID: 33368764).

Hoffmann, E. et al. Outcomes of cryoballoon or radiofrequency ablation in symptomatic paroxysmal or persistent atrial fibrillation. Europace 21, 1313–1324 (2019).

Tondo, C. et al. Pulmonary vein isolation cryoablation for patients with persistent and long-standing persistent atrial fibrillation: Clinical outcomes from the real-world multicenter observational project. Heart Rhythm 15, 363–368 (2018).

Miyazaki, S. et al. Real-world safety profile of atrial fibrillation ablation using a second-generation cryoballoon in Japan: Insight From a large-multicenter observational study. JACC Clin. Electrophysiol. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jacep.2020.11.016 (2021).

Quesada, A., Cózar, R., Anguera, I. & Spanish Catheter Ablation Registry. 19th Official Report of the Heart Rhythm Association of the Spanish Society of Cardiology (2019). Rev. Esp. Cardiol. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.recesp.2020.08.005 (2020).

Hindricks, G. et al. 2020 ESC-Guidelines for the diagnosis and management of atrial fibrillation developed in collaboration with the European Association of Cardio-Thoracic Surgery (EACTS). The Task Force for the diagnosis and management of atrial fibrillation of the European Society of Cardiology (ESC). Eur. Heart J. https://doi.org/10.1093/eurheartj/ehaa612 (2020).

Su, W. et al. Best practice guide for cryoballoon ablation in atrial fibrillation: The compilation experience of more than 3000 procedures. Heart Rhythm 12, 1658–1666 (2015).

Su, W. et al. Cryoballoon Best Practices II: Practical guide to procedural monitoring and dosing during atrial fibrillation ablation from the perspective of experienced users. Heart Rhythm 15, 1348–1355 (2018).

Miyamoto, K. et al. Multicenter Study of the validity of additional freeze cycles for cryoballon ablation in the patients with paroxysmal atrial fibrillation. The AD-Ballon Study. Circ. Arrhythm Eletcrophysiol. https://doi.org/10.1161/CIRCEP.118006989 (2019).

Mörtsell, D. et al. Cryoballoon vs radiofrequency ablation for atrial fibrillation: A study of outcome and safety based on the ESC-EHRA atrial fibrillation ablation long-term registry and the Swedish catheter ablation registry. Europace 21, 581–589 (2019).

Wasserlauf, J. et al. Moderate sedation reduces lab time compared to general anesthesia during cryoballoon ablation for AF without compromising safety or long-term efficacy. Pacing Clin. Electrophysiol. 39, 1359–1365 (2016).

Ferrero-de-Loma-Osorio, A. et al. Time-to-effect-based dosing strategy for cryoballoon ablation in patients with paroxysmal atrial fibrillation: Results of the plusONE Multicenter Randomized Controlled Noninferiority Trial. Circ. Arrhythm. Electrophysiol. 10(12), e005318 (2017).

Aryana, A. et al. Verification of a novel atrial fibrillation cryoablation dosing algorithm guided by time-to-pulmonary-vein isolation: Results from the Cryo-DOSING Study (Cryoballoon-ablation DOSING Based on the Assessment of Time-to-Effect and Pulmonary-Vein Isolation Guidance). Heart Rhythm 14, 1319–1325 (2017).

Chun, J. et al. Individualized cryoballoon energy pulmonary vein isolation guided by real-time pulmonary vein recordings, the randomized ICE-T trial. Heart Rhythm 14, 495–500 (2017).

Iacopino, S. et al. A comparison of acute procedural outcomes within four generations of cryoballoon catheters utilized in the real-world multicenter experience of 1STOP. J. Cardiovasc. Electrophysiol. 31, 80–88 (2020).

Kaitani, K. et al. Efficacy of antiarrhythmic drugs short-term-use after catheter ablation for atrial fibrillation (EAST-AF) trial. Eur. Heart J. 37, 610–618 (2016).

Chen, W. et al. Efficacy of short-term antiarrhythmic drugs use after catheter ablation of atrial fibrillation—A systematic review with meta-analyses and trial sequential analyses of randomized controlled trials. PLoS ONE https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pone.0156121 (2016).

Duytschaever, M. et al. Pulmonary vein isolation with vs without continued antiarrhythmic drug treatment in subjects with Recurrent Atrial Fibrillation (POWDER AF): Results from a multicentre randomized trial. Eur. Heart J. 39, 1429–1437 (2018).

Arbelo, E. et al. The atrial fibrillation ablation pilot study: A European Survey on Methodology and results of catheter ablation for atrial fibrillation conducted by the European Heart Rhythm Association. Eur. Heart J. 35, 1466–1478 (2014).

Bavishi, A. A. et al. Patient characteristics as predictors of recurrence of atrial fibrillation following cryoballoon ablation. Pacing. Clin. Electrophysiol. 42, 694–704 (2019).

Boveda, S. et al. Single-procedure outcomes and quality-of-life improvement 12-months post-cryoballoon ablation in persistent atrial fibrillation: Results from the multicenter CRYO4PERSISTENT AF Trial. JACC Clin. Electrophysiol. 4(11), 1440–1447 (2018).

Kuck, K. H. et al. Impact of female sex on clinical outcomes in the FIRE AND ICE trial of catheter ablation for atrial fibrillation. Circ. Arrhtyhmia Electrophysiol. 11, e006204 (2018).

Liu, J. et al. Early recurrence of atrial tachyarrhythmia during the 90-day blanking period after cryoballoon ablation in patients with atrial fibrillation: The characteristics and predictive value of early recurrence on long-term outcomes. J. Electrocardiol. 58, 46–50 (2020).

Uetake, S. et al. Re-definition of blanking period in radiofrequency catheter ablation of atrial fibrillation in the contact force era. J. Cardiovasc. Electrophysiol. https://doi.org/10.1111/jce.14643 (2020).

Acknowledgements

The RECABA investigators want to express their gratitude to the coordinators and electrophysiological teams of all the Spanish centers who have participated in a voluntary and altruistic way in the registry. We also are grateful to Kendra Braegelmann, from Medtronic, and especially with Miguel Angel Ruiz Díaz from Universidad Autónoma (Madrid), for the statistical analysis support.

Funding

This research was supported by Medtronic Iberia, S.A.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Consortia

Contributions

A.F., R.C., A.G., E.V., P.P., I.M., J.M.-A. have contributed to study design, interpretation of results and manuscript development, A.B., J.T., J.O., J.S., R.R., P.B., J.M.R., J.M.A. have contributed to critical review of the manuscript. All authors have read and approved this manuscript submission and included full disclosures of any potential conflicts of interest.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

Dr. Toquero is member of the Medtronic European advisory board. Dr. Toquero,, Dr. Cózar, Dr. Barrera have received speaker honorarium from Medtronic. Dr. Toquero and Dr. García-Aberola have received educational grant from Medtronic. Dr. Martinez Alday has received speaker honorarium from Medtronic, Boston Scientific and Abbott Laboratories. Dr. Ferrero and Dr. Ruiz have received speaker honorarium from Medtronic and Boston Scientific. Patricia Pascual and Irene Molina are employees of Medtronic Iberia, S.A. Rest of authors declare no competing interest.

Additional information

Publisher's note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Supplementary Information

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License, which permits use, sharing, adaptation, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if changes were made. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article's Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article's Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Ferrero-De-Loma-Osorio, Á., Cózar, R., García-Alberola, A. et al. Primary results of the Spanish Cryoballoon Ablation Registry: acute and long-term outcomes of the RECABA study. Sci Rep 11, 17268 (2021). https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-021-96655-3

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-021-96655-3

This article is cited by

-

Safety and long-term efficacy of cryoballoon ablation for atrial fibrillation in octogenarians: a multicenter experience

Journal of Interventional Cardiac Electrophysiology (2022)

Comments

By submitting a comment you agree to abide by our Terms and Community Guidelines. If you find something abusive or that does not comply with our terms or guidelines please flag it as inappropriate.