Abstract

We use nationally representative data from two waves of the Indian Human Development Survey to examine the role of inter-temporal changes in fertility behavior in influencing female labor market outcomes. Our multivariate regression estimates show that an increase in the number of children reduces labor force participation and earnings. We further investigated the impact of fertility changes on transitions from the labor market. The results show that women who had more than three children in both rounds of the survey had a 3.5% points higher probability of exiting from the labor market than their counterparts with two or fewer children net of other socio-demographic factors. Disaggregated analyses by caste, economic, educational status, and region show that the probability of dropping out of the labor market due to fertility changes varies by region and is greater for non-poor and primary to secondary schooling women and those from socially disadvantaged castes than poor, non-educated, and socially advantageous women.

Similar content being viewed by others

Avoid common mistakes on your manuscript.

Introduction

Economists and demographers have long hypothesized a negative relationship between reproductive burden and female workforce participation (Adair et al., 2002; Bloom et al., 2009; Cruces & Galiani, 2007). The main argument is that higher fertility is associated with a lower female labor force participation rate due to caring responsibilities for young children which falls disproportionately on women- termed as the ‘motherhood penalty’ (Correll and Benard, 2007; Francavilla & Giannelli, 2011). In lower middle-income countries, despite the expansion of education, job opportunities for women, and fertility decline, the female labor force participation rate (FLFPR) either has been stagnant or has fallen over time (Bongaarts et al., 2019; Kuhn et al., 2018; Sarkar et al., 2019).

India presents a good case in this regard. Despite a significant fall in fertility rates accompanied by an increase in real economic growth and rising female education over the last two decades, India’s FLFPR has declined from approximately 40 per cent in 1993–94 to 20.33 per cent in 2019 (Chaudhary & Verick, 2014; Desai & Joshi, 2019; International Labor Organization [ILO], 2020), despite a period of the favorable demographic outlook for India. According to the latest Census (2011) estimates, 60.1 per cent of India’s population is in the working-age group (15–64 years), and this is projected to remain at around 58 per cent in 2050 (MOHFW, 2019). As women constitute almost half of the Indian population, a declining FLFP may inhibit economic growth and development and adversely affect the prospects of reaping the demographic dividend (James & Goli, 2016).

Previous research has attributed the low or falling FLFP in India to factors such as lack of availability of appropriate data (Hirway & Jose, 2011); low levels of education and the informal nature of female work (Thomas, 2012); low wages and discrimination in labor markets (Thomas, 2012; Kapsos et al., 2014); and household and individual-specific factors (Chaudhary & Verick, 2014; Das et al., 2015a; Afridi et al., 2017; Sarkar et al., 2019).

The aim of this paper is to use nationally representative data from the two waves of the the Indian Human Development Survey (IHDS) to empirically analyze the inter-temporal links between fertility behavior and female labor market outcomes. The IHDS survey was conducted in 2004–2005 and 2011–2012, and a key advantage of our analysis is that we are able to observe the same women at two points in time. To the best of our knowledge, the association between the decline in reproductive burden and female labor market outcomes has not been studied in India using panel data. In particular, the literature does not specifically explain whether reducing reproductive burden can have an influence on female labor market outcomes. Our study addresses this research gap and contributes to several strands of the literature.

Firstly, the low female labor force participation and the decline or stagnation in female labor force participation in India are a puzzle that the current literature has been unable to explain, mainly due to a lack of appropriate data. Against this backdrop, our study sheds some light on the causal relationship between change in reproductive burden and FLFP. The use of a panel dataset allows us to conduct a more nuanced analysis of the dynamics of FLFP of the same women over a seven-year period and explicitly investigate the role of reproductive burden in influencing labor market transitions net of other factors. In particular, we estimate the rates of female entry and exit from the labor market, in response to changes in their reproductive burden and heterogeneity across caste, economic status, and regional backgrounds. We measure reproductive burden by the number of children ever born and pregnancy status at the time of the survey in both rounds.

Secondly, although Sarkar et al. (2019) and Dhanaraj and Mahambare (2019) have investigated female entry and exit from employment using the same panel dataset as in our study, their focus is not specifically on the relationship between fertility change and employment dynamics. A crucial distinction of our study from other related literature is that we explicitly consider inter-temporal changes in reproductive burden and its impact on women’s labor supply decisions. This includes their decision to enter or exit out of employment, reduce or increase hours of work and the impact on earnings. By estimating distinct probabilities of entry and exit out of employment in response to fertility changes, we provide more nuanced evidence on the role played by fertility changes on FLFP.

Thirdly, the role of fertility and subsequent reproductive burden on female labor supply decisions appears to have received relatively little attention in studies from India. Fewer children may improve the overall well-being of women and increase their opportunity to engage in the labor market and earnings (Adair et al., 2002). Early marriage and childbearing are often found to be associated with higher fertility levels and lower education, thus depressing FLFP (Goli, 2016; Yount et al., 2018; Selwaness & Krafft, 2020). However, there is a dearth of causal evidence from India on the links between the motherhood penalty and FLFP. By incorporating the dynamics of fertility behavior and pregnancy status explicitly in the analysis, we are able to provide a more nuanced explanation of the role of children on female labor force participation than is provided by current literature. While studies such as Sarkar et al. (2019) and Dhanaraj and Mahambare (2019) also study FLFP using the same panel dataset as ours, their focus is on the role of culture, income, family structure, and education.

Fourthly, while existing studies (Agüero & Marks, 2011; Francavilla & Giannelli, 2011) have attempted to capture the impact of fertility on FLFP using binary information (working or not working), they did not assess the role of fertility changes on the intensity of labor force participation. As observed by Heath (2017), an examination of the impact of fertility change on the full spectrum of labor market outcomes can provide greater insights for more nuanced policy intervention. Our study considers the full spectrum of labor supply decisions by incorporating information on hours of work and wage earnings besides labor market participation. Studies using the macro-level or cross-sectional association between fertility levels and FLFP fail to capture inter-temporal transitions or dynamics in labor supply decisions (Klasen & Pieters, 2015; Das & Žumbytė, 2017; Bonggarts et al., 2019). Using disaggregated analyses by caste, economic status, education, and region, we specifically assess the sensitiveness of the relationship between reproductive burden and labor market outcomes to woman’s socio-economic background and regions.

Our main results may be summarized as follows. We show that women who had additional children during the period, 2004–2012 or became pregnant by the second wave of the survey, are relatively more likely to have dropped out of the labor market, worked fewer hours, and earned less than respondents with no changes in their fertility levels. We further show that reproductive burden has differential implications for women from different regions and socio-economic backgrounds.

The rest of the paper is organized as follows. Section 2 provides a literature review of the relationship between fertility and labor force participation and background context. Section 3 describes the data source and variables considered in our analysis, and the empirical strategy adopted. Section 4 reports the results from the econometric analysis. The concluding section discusses the key findings and the policy imperatives arising from this study.

Background and Literature Review

The negative relationship between fertility and FLFP is well established in the economics literature starting from the seminal contribution of Becker (1960). Subsequent empirical studies (Ashenfelter & Heckman, 1974; Mincer, 1962) have also found evidence of an inverse relationship between fertility and FLFP. In the last two decades, there have been attempts to analyze the effects of fertility on labor market outcomes in a variety of settings and the evidence on the relationship between fertility and women’s employment at the micro-level is very wide (Matysiak & Vignoli, 2008). In this section, we reviewed the existing international literature on motherhood penalty in two separate categories of the labor market outcomes: (i) motherhood penalty and employment status (working/not working), (ii) motherhood and wage penalty, and then (iii) we discuss the existing studies in the Indian context.

Motherhood and the Employment Status

In the first section, we reviewed studies that investigated the relationship between motherhood and the employment status (working or not working). Most of the studies found that fertility reduces FLFP among women (Bloom et al., 2009; Cáceres-Delpiano, 2012; Chun & Oh, 2002; Cruces & Galiani, 2007; Ebenstein, 2009; He & Zhu, 2016). Cruces and Galiani (2007) found that having more than two children reduces a mother’s supply by about 8.1–9.6% points in Argentina and by about 6.3–8.6% points in Mexico. Similarly, for 97 countries, Bloom et al. (2009) conclude that women’s labor supply reduces by almost 2 years during her reproductive life following a birth. Cáceres-Delpiano (2012) for developing countries also find that having children has a negative impact on female employment, whereas some studies found a little or no impact on the other hand. For example, Chun and Oh (2002) for Korea found that having children reduces the labor force participation among married women. For 26 developing countries, Ebenstein (2009) concluded that labor force participation among younger women from poorer countries is marginally reduced by having children. Similarly, He and Zhu (2016) also found a very small negative effect of increase in children on FLFP. On the contrary, Drobnicˇ (2000) for US, Giannelli (1996) for West Germany, and Leth-Sørensen and Rohwer (2001) for Denmark found no significant effect of young children on entry into employment or employment in general (Felmlee, 1993; Bernardi, 2001). In Asian countries too, Azimi (2015) for urban Iran did not find any significant effect of children on FLFP. On the other hand, some studies from US (Grunow et al., 2006; Hofmeister, 2006) and Denmark (Grimm & Bonneuil, 2001) have suggested that mothers of young children have more probability to enter employment than other women. A recent study using European data has found that increase in the number of children is associated with higher male labor supply (Baranowska-Rataj and Matysiak, 2022).

Thus, though the empirical evidence on the issue is very large, it is difficult to draw conclusion with several contradictory results.

Motherhood and Wage Penalty

In this section, we reviewed studies which investigated the impact of fertility on women earnings or the wage penalty of having children. Empirical studies by Budig and England (2001) and Correll et al. (2007) have found evidence of a substantial wage penalty for mothers. Studies find that with an increase in children, women shift to a lower-paying job without increasing hours, thus childbearing was found to be associated with lower income (Cáceres-Delpiano, 2012; Heath, 2017), especially for those in self-employment (Ajefu, 2019). In the context of the Philippines, Adair et al. (2002) have found that having two or more additional children born over an 8-year interval significantly reduced women’s earnings, while having an additional child under two years of age reduced hours worked. On the contrary, Rammohan and Whelan (2005) did not find any significant impact of fertility on women’s labor supply and work hours in Australia.

In this study, we assume that the discussion on the motherhood penalty is situated in the normative construction of motherhood and the gendered nature of caregiving or work sharing at the family or household level which varies considerably across time, countries, and socio-cultural contexts. It is therefore vital to explore the effects of childbearing not only on employment status, but also on hours allocated for paid work and earnings, especially in a highly patriarchal society such as India.

Studies from India

India is an exception with low and falling FLFP combined with high economic growth, declining fertility, and rising education levels. Reasons for the low rates and declining trend in FLFP in India have been widely studied. As previously discussed, explanations include the lack of availability of appropriate measurement of FLFP (Desai & Joshi, 2019; Hirway & Jose, 2011), informal nature of work (Thomas, 2012), unequal wages (Thomas, 2012; Kapsos et al. 2014), and other household and individual-specific factors (Chaudhary & Verick, 2014; Das et al., 2015b; Afridi et al., 2017; Verick, 2018).

The strand of research that examines the relationship between fertility and labor supply to explain the recent decline in FLFP in India ( Sengupta & Das, 2014; Sorsa et al., 2015; Klasen & Pieters, 2015; Lahoti & Swaminathan, 2016; Afridi et al. 2019) reports contradictory findings similar to the international literature. Also, the literature from India is highly heterogeneous in terms of differences in terms of findings, coverage, and methodologies adopted. Both Sorsa et al. (2015) and Klasen and Pieters (2015) have focused on urban women specifically and found an increasingly negative association between the presence of young children and female labor force participation. Chatterjee et al. (2015) focus on the presence of older family members who may act as alternative care givers to facilitate female labor force participation. Similarly, although Das and Žumbytė’s (2017) study on the impact of young children on FLFP found a negative association between the presence of young children and FLFP over time, their study used repeated cross-section data, so they do not observe the same women over time as our study does. Afridi et al. (2017) found that higher perceived returns from home-based employment relative to market-based employment reduced female labor force participation. More recently, Afridi et al. (2019) show that the productivity of home-based work is higher than market-based employment for women in India, and the prevailing gendered division of labor at the households acts as a binding constraint for women's labor supply.

Summing up, previous research on factors influencing the low FLFP in India in general and the relationship between fertility and female labor market outcomes, in particular, has at least three limitations. First, these studies have typically used a binary variable to capture the female decision of whether or not to be employed, making it difficult to generalize their results at the intensive margin. Second, the lack of availability of a panel dataset in India has been a major constraint in analyzing the implications of changes in fertility on female labor market decisions, especially those who have joined or dropped out of the workforce in response to changes in the number of children ever born. Third, children are included as a control variable and the dynamics of changes in fertility behavior on labor market transitions has not been explicitly studied. As described above, our analyses focus on the same women who are observed in two survey waves over a seven-year period, providing a dynamic perspective on the role of children in female transitions in and out of the labor market, focusing on not just whether they participate in the labor market, but also on the number of hours spent on work and their wage earnings. Additionally, we assess the heterogeneity of dynamics in fertility behavior on female employment across caste, economic status, and region.

Data and Econometric Strategy

The data used in the analyses come from two waves of the nationally representative Indian Human Development Survey (IHDS) conducted in 2004–2005 and 2011–2012. The IHDS survey is a collaborative project of the University of Maryland, the USA, and the National Council of Applied Economic Research (NCAER), India. The survey uses a multi-stage cluster sampling design for the data collection. The survey provides detailed information about household and individual socio-economic and demographic characteristics.

The sample for our analysis includes 26,830 ever-married women aged 15–49 years in 2004–2005. Of the original sample (33,482 women aged 15–49 years in 2005), there are 6652 women for whom there is no follow-up information in 2012 due to household attrition, death, or moving to other places. Some of the women are dropped from the sample as they are above childbearing age, i.e., 49 years. Considering that the survey could only be re-administered for 80.13 per cent of the sample (26, 830 out of 33,482 women) in the second wave, we have first addressed the issue of observable determinants of attrition in Table 1. The determinants of attrition between the two rounds are reported in Table 1. For this study, we use information on the fertility history of women of childbearing age and her labor market participation besides other socio-economic and demographic characteristics. The results suggest that the variables of interest are found to be significantly correlated with attrition rates. Therefore, the panel data fixed-effects regression model in the next section include the selection inverse mills ratio \((\lambda\)) in the estimation process.

Dependent Variables

To investigate the impact of fertility change on female labor supply, we consider three dependent variables. These include the following: (i) working = 1 if the female respondent reported that she was currently in wage employment, 0 otherwise. For those women who have participated in the labor market, two separate analyses were conducted at both the extensive and intensive margins using (ii) the total annual hours worked, and (iii) the annual earnings in the 12 months prior to the survey. Although estimates for the intensive margin cannot provide overall causal estimates of the impact of having children on the female labor supply, they can be interpreted as a decomposition of the overall effects. They show how female labor supply differs during a period where the female respondent had fewer children compared to a period where there are more children. Table 2 presents all the variables included in the empirical analyses.

We observe that the FLFP was similar across the two waves, with approximately 25 per cent of the sample participating in the labor market in both periods, 2004–2005 and 2011–2012 (Table 2). These figures are consistent with the figures reported in the NSS data. However, some women have exited the labor market while others have entered the labor market during this period. We also observe that the hours worked (6.91 h/ per day) in 2004–2005 dropped slightly to 6.75 in 2011–2012, whereas the earnings have increased slightly. To depict the causal relationship between fertility and labor force participation, we have estimated the effect of fertility change on women’s employment transitions. In particular, we have examined the factors influencing woman’s decisions to enter into and exit from the labor market, in response to fertility changes.

Explanatory Variables

Our explanatory variables include variables reflecting the respondent’s socio-economic, demographic, and household decision-making autonomy (Table 2). Our sample is predominantly rural with only 31% of the respondents living in urban areas (Table 2). The fertility behavior of respondents is a key explanatory variable in this study. In our analyses, we include three variables relating to the respondent’s fertility behavior: (1) the total number of children she has given birth to, (2) whether she is currently pregnant, and (3) the number of pre-school age children (under five years of age). On average, a woman respondent had 2.67 children in 2004–2005, increasing to 2.91 in 2011–2012. Around 5% of the respondents were pregnant in the 2004–05 survey, which dropped to 1% in the 2011–2012 survey (Table 2). Nearly 51% of the sample had children under 5 years of age in 2004–2005, dropping to 46% in 2011–2012.

The respondent’s economic status is measured using a wealth index based on information on assets available in the IHDS survey. The wealth index takes into account household assets and is constructed using principal components analysis. Based on wealth scores, respondents are categorized into five wealth quintiles. As wealth-based quintiles may not reflect poverty, in some descriptive analyses, we have also used absolute poverty measure (Tendulkar poverty line) to classify households below the poverty line (poor) and above poverty line (non-poor) based on monthly per capita consumption expenditure (see Desai et al., 2010 for details on the methodology).

We observe that education levels are generally low in the sample, with nearly half the sample (47%) having no education in 2004–2005, which slightly reduces to 44% in 2011–2012, and around 17% reporting having education up to the primary schooling level (Table 2).

India is a society with traditional social norms that constrain women from working outside the household, and women’s autonomy is an important consideration for their ability to participate in the labor market (Kambhampati, 2009; Rammohan & Vu, 2018). The IHDS survey has detailed questions on decision-making autonomy for women in the household with regard to an array of household decisions. These include decision-making autonomy relating to large household purchases, family size (the number of children), say on medical treatment for children, and children’s marriage. For each of these decisions, if the respondent reports that she is involved in household decision-making either solely or in consultation with other household members (such as her husband or other household members), we assume that she has decision-making autonomy, and the variable takes on a value of 1, and 0 otherwise. The Autonomy Index sums all the five aspects of household decision-making, so the variable ranges between a maximum value of 5 and a minimum value of 0 for those women with no decision-making autonomy. Based on this, women are grouped into three categories—high, medium, and low household decision-making autonomy. Women’s autonomy is generally low in our sample, with 65% of the respondents in the low autonomy category in 2004–2005, which drops slightly to 61% in 2011–2012. Only 7% of the respondents were in the high autonomy category, which increased to 11% in 2011–2012 (Table 2).

It is also noteworthy that 27% of the respondents lived in a joint family household structure in 2004–2005, increasing to 37% in 2011–2012. While the presence of other adult members in the household provides alternative sources of child care and may increase the potential for women to participate in the labor market, the presence of other adults may also mean that there are greater restrictions on women.

Respondent’s health is also found to be an important factor influencing labor market participation (Goryakin et al., 2014; Heath, 2017). Based on self-reported responses, the respondent’s health status is categorized into the following three discrete categories; Good, OK, and Bad. Further, we take into account the female respondent’s membership of social networks which may influence their ability to find a job (Raeymaeckers et al., 2008). The variable social network takes on a value of 1 if the respondent or any other family member reported being a member of organizations such as women’s groups (Mahila Mandal), youth club, employee union, self-help group, credit/saving group, caste/ religious group, non-government organization (NGO), or any political party. We further take into account access to government transfers, by defining a variable ‘government benefits’ which takes on a value of 1 if the household received any income from government benefit schemes such as drought/flood compensation, insurance pay-out, or any other in the last one year, otherwise categorized as 0.

Descriptive Analysis

In Figs. 1, 23, 4 , and 5, we present trends in women’s employment in our sample based on their economic status and fertility behavior. A large literature has established that in low-income settings, the labor force participation of females follows a U-shape when plotted against income (Gaddis & Klasen, 2014; Tam, 2011). FLFP is generally high at low levels of income (as women work out of necessity to contribute to household income), and it then falls among middle-income households, but again rises for women in high-income households (Bhattacharya & Haldar, 2020; Pradhan et al. 2015). This is also observed in our data as shown in Fig. 1. The labor force participation among the poor has remained constant at around 38% in both periods. Although female labor force participation in non-poor households remains below that of poor women, it has increased by nearly 8% points over the period. About 20% of non-poor women were working in 2004–2005 which increased to 28% in 2011–2012.

Figure 1 also shows women’s employment by fertility levels. A key point to note here is that across all three categories (no child, 2 or fewer children, greater than 2 children), there is an increase in female labor force participation in our sample between 2004–2005 and 2011–2012. In particular, the labor force participation among women with no children increases from 19.6% in 2004–2005 to 35.5% in 2011–2012. On the other hand, the increase in labor market participation among women with more than two children increased by only 2% between 2004–2005 and 2011–12. These trends reflect the important role that the presence of children plays in women’s decision to enter the labor market.

In Fig. 2, we plot the transitions into and out of the labor market between 2004–2005 and 2011–12 by fertility behavior, separately for poor and non-poor women. As shown in Fig. 2, one common observation across both poor and non-poor women is that those with less than two children represent the highest proportion of labor market entrants in both survey rounds. On the other hand, we observe that in both surveys, among women in the poor category with more than two children, a higher proportion dropped out of the labor market (18.47%) relative to those who joined the labor market (16.02%). Among non-poor women, however, we observe substantially large increases in labor market participation, albeit from lower levels. In particular, for women with more than two children, we observe that while 9% dropped out of the workforce between 2004–2005 and 2011–2012, 14.84% of women joined the workforce.

In Figs. 3 and 4, we plot the annual hours worked and wage earnings of women, disaggregated by their poverty status and fertility behavior, respectively. Although poor women have higher labor market participation rates as shown in Fig. 1, Fig. 3 shows that their annual hours of work is lower than those for non-poor women. However, with an increase in fertility, average annual hours of work slightly increased for poor women, but considerably declined among non-poor women. Figure 4 shows an overall increase in earnings for all women during the period between 2004–2005 and 2011–2012. Although the numbers are not inflation adjusted, we observe significantly higher earnings for women with two or less than two children with reference to those with higher than two children both in poor and in non-poor households.

In 2005, the Government of India introduced a major social welfare program called the Mahatma Gandhi National Rural Employment Guarantee Scheme (MGNREGA) to increase the labor force participation in rural areas. Since the introduction of the program was after Wave 1 (2004–2005) but before Wave 2 (2011–2012) of our survey, we have plotted the trends in workforce participation rates, hours of work, and earnings separately for rural areas in Fig. 5. The largest exit from the labor market is for those women who had less than 2 children in 2004–2005, but had more than 2 children in 2011–2012. Notably, we observe that annual hours of work declined for all three groups (women with less than 2 children in both waves, women with less than two children in 2004–2005 but more than 2 children in 2011–2012, and women with more than 2 children in both waves). However, the largest decline in annual working hours was observed for those women who had less than 2 children in 2004–2005, but more than two children in 2011–2012. We observe that annual earnings increased over this period for rural women. Despite a slight rise in overall employment for females and the movement of labor from farm to the non-farm sector (Desai, 2018), the female labor market outcomes in response to the inter-temporal change in their fertility levels have been remained similar throughout 2004–2005 to 2011–2012 (Fig. 1,2, 3 and 4). This re-emphasizes the robustness of the hypotheses that are being tested in this study.

Econometric Methodology

In order to study the links between fertility and female labor market outcomes, using data from the IHDS survey, we first estimate a fixed-effects panel regression model as shown in Eq. 1. The fixed-effects model is used to account for women-level unobservable factors that may have an impact on both fertility and female labor market outcomes.

The main equation of interest takes the following form:

where \({Y}_{\mathrm{it}}\) represents the labor market outcome of women \(i\) at time \(t\), \({\mathrm{Child}}_{\mathrm{it}}\) refers to the number of children that women i has at time t, \({\alpha }_{1i}\) represents the constant term. \({X\mathrm{^{\prime}}}_{\mathrm{it}}\) is a vector of other time-varying variables such as the woman respondent’s health, autonomy, and economic status. \({\lambda }_{\mathrm{it}}\) is the selection inverse mill ratio included in the model as an additional regressor to avoid selection bias. We use age dummies to control for the flexibility of the labor market changes with women’s age.

The coefficient \(\gamma\) in Eq. 1 compares female’s labor market outcomes for over two periods (2004–2005-2011–2012)-one with fewer children and another when the number of children has increased. In the current context, the model provides the average response across women who indicated that they worked more or fewer hours as there was an increase in the number of children they had. We include an additional variable for the Inverse Mill Ratio for fixed-effect regression, which is estimated based on attrition in the sample between 2004–2005 and 2011–2012.

In the next stage, since women with young children have a higher opportunity cost of working, we include the presence of young children (less than 5 years of age) and other household members as additional variables that may influence female labor supply. The relationship between fertility and employment dynamics adjusting for the heterogeneity in the household composition is presented in the robustness checks at a later stage in the paper.

The estimated \(\gamma\) reflects the unbiased impact of having children on female labor market outcomes, if and only if the current number of children is uncorrelated with the time-varying determinants of labor supply, i.e., \(E\left({\mathrm{Child}}_{\mathrm{it}}{\varepsilon }_{1\mathrm{it}}|{\alpha }_{1i}\right)=0\). We test the robustness of our results for potential endogeneity by regressing current fertility on lagged labor market outcomes at a later stage in the paper.

In the second stage, considering that two out of our three dependent variables (i.e., hours worked and earnings) may have many zero responses, due to respondents choosing not to work or lack of employment opportunities, we use a truncated sample (only non-zero cases) in Eq. (2). The dependent variable is a continuous variable and no zeros are allowed (truncated at zero). Accordingly, we observe the working hours for a sample of working women or the sample of women with positive earnings. Therefore, we estimate a Tobit regression model including the censored sample (cases with zero value). However, because of censoring, the dependent variable y is the incompletely observed value of the latent dependent variable \(y*\). The Tobit model is the censored normal regression model which is formally given by:

However, there is potential for sample selection bias since the researcher does not observe the reasons for respondents not engaging with the labor market. Therefore, we estimate a Heckman sample selection model. Sample selection (incidental truncation) is different from the truncation criteria used in Eq. (2). For instance, we do not observe the hours of work or income for women who are not engaged in the labor market. Thus, sample selection assumes that the discrete decision z and the continuous decision y have a bivariate distribution with correlation ρ. The equation of interest in such models for the selected sample takes the following form:

where the inverse mills ratio is \(\widehat{{\lambda }_{\mathrm{it}} } ({W}^{\prime }\upgamma )\).

Finally, taking advantage of the longitudinal nature of the dataset, we estimate employment transition probabilities in response to fertility changes. In particular, we are interested in estimating how the probabilities of entry into and exit from the labor market are affected by changes in female fertility level, controlling for the socio-economic and demographic characteristics of the respondent and their household. To this end, we estimate two separate Probit regression models for entry and exit into the labor force, which can be formally written as follows:

The dependent variable in Eq. (4) is a binary indicator of whether a woman has entered into employment between 2004–2005 and 2011–2012.\(\upphi\) in the equation represents the cumulative standard normal distribution of the dependent variable. Similarly, in Eq. (5), the dependent variable is a binary indicator of whether a woman has exited from the employment between 2004–2005 and 2011–2012. \({Child}_{i}\) refers to the change in the number of female i’s children between 2004–2005 and 2011–2012, \({X\mathrm{^{\prime}}}_{i}\) is a vector of other control variables such as woman’s health and economic status.

Estimation Results

We present the results of our estimation in Tables 3, 4, 5, 6, 7 and 8. The main results of our analyses are summarized as follows: (i) the presence of an additional child reduces both the probability of a women being in paid employment and annual earnings; (ii) women with more than 3 children in both rounds of the survey had a 3.5% points higher probability of exiting from the labor market; and finally, (iii) pregnancy status does not influence labor market outcomes in the fixed-effects model. Below we discuss these results in more detail.

Fixed-Effects Estimates

Table 3 reports the estimation results from the fixed-effects model showing the influence of having children on female labor market outcomes. The first three columns show the impact of fertility on labor force participation decisions. In col. 1, we observe that the coefficient for the variable ‘total children’ is statistically significant and negatively signed showing that the presence of an additional child is associated with a 1% point decline that the women is in paid employment. In col. 2, we show that the presence of young children decreases the probability of a women being in paid employment by 0.2% points. In Col. 3, we observe that with the inclusion of a dummy variable for the presence of a young child, the variable total children is no longer statistically significant. This suggests that the overall negative impact of children on female labor force participation at the extensive margin is primarily driven by the presence of young children. In keeping with Heath's (2017) study of urban Ghana, the variable pregnancy status is not statistically significant.

The results in Column 4 show that the number of children and the presence of a young child aged below 5 are not statistically significant. However, in Column 6, the presence of a young child is statistically significant and negatively signed. Notably, the coefficient for pregnancy remained statistically insignificant across all the models.

Heckman Selection Model Estimates

The results from the Heckman model (second stage) are presented in Col. 5 and 8 of Table 3, for hours worked and annual earnings, respectively, for the sample of employed women. The results indicate that the total number of children is not statistically significant. However, a respondent’s pregnancy status reduces her work hours by 36% points (Col. 5, Table 3). In contrast to the estimates from the fixed-effects model, in the Heckman model, the presence of a young child is not statistically significant in influencing female working hours. Nevertheless, pregnancy is negatively associated with hours of work.

Tobit Model Estimation

Since the truncated sample is not representative of the population and also implies loss of information, we present empirical estimates from a Tobit regression model. The results presented in Table 3 (Col. 6 and 9) show the impact of changes in fertility on hours worked and annual earnings, respectively. The Tobit estimates show a significantly negative influence of pregnancy and children on female hours worked and annual earnings. The findings presented in Col. 6 based on the censored normal regression show that an increase in the number of children decreases female working hours by nearly 3.6% points and annual earnings by 6% points (Col. 9, Table 3). From Col. 6, we further observe that the presence of young children significantly reduces working hours by 7% points.

Fertility Transitions and Changes in Labor Market Outcomes

Using the longitudinal nature of our survey, we analyze the impact of fertility transitions on entry into and exit from the labor market in the two waves. Specifically, we estimate Probit regression models for the probability of (i) a woman who was not employed in 2004–2005 entering the labor market in 2011–2012 and (ii) a woman who was employed in 2004–2005 exiting the labor market in 2011–2012. Fertility transition is captured as follows: women with < 2 children in both 2004–2005 and 2011–2012; < 2 or 2 in 2004–2005 but > 2 in 2011–2012; > 2 in 2004–2005 and in 2011–2012. The explanatory variables used in this model are the same as in the previous models.

The results are reported in Table 4 (Cols 1 and 2) for women who entered the labor market in 2011, and in Cols 3 and 4 for those who exited the labor market (Cols 3 and 4). In Table 4, the first two columns show the impact of having additional children on the probability of a woman entering the labor market in 2011–2012 (i.e., if she was not employed in the first round but reported being employed in the second round). As with previous results, Col 1 of Table 4 shows that the presence of an additional child reduces the probability of a woman joining the labor market by 2% points. In Col. 2, we include variables relating to fertility transitions. The results indicate that relative to women who had less than two children in both 2004–2005 and 2011–2012, an increase in the number of children is statistically significant and negatively associated with joining the labor market. Having an additional child by the second wave of the survey reduces the probability of a non-employed woman joining the workforce by nearly 3% points.

In Cols 3 and 4 of Table 4, we investigate the impact of fertility changes on exit from the labor market (i.e., if a woman reported working in the first round but not working in the second round). The results show that women who had more than 3 children in both rounds of the survey had a 3.5% points higher probability of exiting from the labor market.

Heterogeneous Effects

In this section, we examine socio-economic and regional heterogeneity in fertility transition and its influence on changes in labor market outcomes. Previous literature has documented the importance of caste, economic status, and regional factors as being influential forces in determining fertility, women’s status and her employment (Drèze and Sen, 1997; Sundaram & Vanneman, 2008; Rammohan & Vu, 2018; Deshpande et al. 2018).

Effects of Fertility Changes on FLFP by Caste

Caste is an important marker of social discrimination in India (Deshpande, 2011). The Indian constitution has made caste discrimination unlawful and there are affirmative action policies to address inequities in education and labor market opportunities for members of disadvantaged castes. Despite this, wide differences are observed in both the fertility outcomes and labor force participation depending on caste status. A recent study by Deshpande et al. (2018) finds that between 1999–2000 and 2009–2010, there was a 7% points decrease in the participation of upper-caste women in regular salaried employment. On the other hand, there was an increase in the labor force participation of women from Scheduled castes (SCs), Scheduled Tribes (STs), and Other Backward Classes (OBCs), over this period. Table 5 presents the results from analyzing the heterogeneous effects of changes in fertility on female labor market transitions, disaggregated by caste status. Since we are observing the same women at two points in time and caste is a time-invariant variable, we can observe the propensity for women to join or drop out of the labor market within each caste category. Our analyses show that the probability of a woman from a Scheduled Caste (SC)/Scheduled Tribe (ST) background to re-join the workforce after having additional children is 4.1% points lower for women from the socially disadvantaged SC/ST groups, and 2.6% points lower for women from the OBC group. Similarly, women from SC/ST are 5.2% points more likely to drop out of work after having children. We do not observe any statistically significant effects for women from the General category.

Effects of Fertility Changes on FLFP by Economic Status

In Figs. 2, 3, and 4 , we show differences in women’s labor force participation, hours worked, and earnings by economic status. In Table 6 , we present regression results on the role of children in influencing transition into and out of the workforce disaggregated by economic status.

Our analysis shows that both poor and non-poor women are 4% points more likely to drop out of the labor force after having children. However, non-poor women have a significantly lower probability of re-joining the labor force after having children. It may be because non-poor women engage more in formal employment with maternity leave entitlements compared to poorer women, thereby increasing their probability of re-entering the labor market (Klasen & Pieters, 2015).

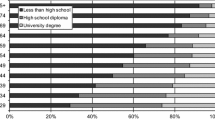

Effects of Fertility Changes on FLFP by Education Levels

The ‘U-shape’ relationship between female education and employment has long been discussed in the literature (Chatterjee et al., 2018)). Keeping this in view, we have modeled separate estimates for four different educational categories of women: no education, below primary schooling, primary to secondary schooling, and graduate and above. The results in Table 7 reveal that drop-out of employment is significant for women with primary to secondary schooling. These results in tune with previous literature that shown women in middle education category are vulnerable in the labor market.

Effects of Fertility Changes on FLFP by Region

In seminal work, Dyson and Moore (1983) have attributed differences in demographic outcomes (child mortality and fertility) to differences in kinship systems in North and South India. Following this, studies from India have incorporated the long-standing regional socio-cultural differences in studies on gender differences (Drèze and Sen 1997; Kishor, 1993; Rammohan & Vu, 2018; Kambhampati & Rajan, 2008; Sundaram & Vanneman, 2008). North-Western India is typically characterized as having kinship structures that disadvantage women as demonstrated in demographic outcomes from northern India compared to the South and the West. In Table 8, we conduct disaggregated analyses to examine whether the transitions into and exit from the labor force differ by regions in response to changes in reproductive burden. Our results are in line with the literature, whereby women from the Northern states and the western states are significantly less likely to join the labor force after the birth of the children. However, dropping out of the labor market due to children is greater in women from eastern and southern regions. This may be because labor force participation is higher in these regions (Drèze and Sen 1997), so we observe a higher proportion of women dropping out in these regions, relative to the reference category.

Robustness Checks

Lagged Labor Market Outcomes and Fertility Decisions

The results reported above are only valid under the assumption that fertility is not related to labor market shocks during the survey period. To check for this possibility, we regressed fertility levels on lagged labor outcome variables, given by:

where \({Y}_{\mathrm{it}-1}\) represents the female labor market outcome variables in the previous survey period. Appendix 1 reports the estimated results for Eq. (7). We do not find any statistically significant evidence for the influence of lagged labor market outcomes on the number of children. Therefore, these results rule out reverse causality from the estimates shown in the previous sections.

Household Composition, Fertility Levels, and Female Labor Force Participation

The availability of alternative care givers in the household may enable greater female labor force participation. However, a recent study by Dhanaraj and Mahambare (2019) using the same dataset as in this study finds that the joint family structure lowers female labor force participation in non-farm employment by 12% points. However, their focus is on education and not on fertility burden. In Appendix 2, we test whether household composition, in particular living in joint families, which provides access to alternative sources of caregivers for children affects female labor supply. The results (col. 1 & 2) show that on average women living in joint families have a lower probability of working, and the presence of other adults and teenage siblings does not increase labor market participation. The presence of an older woman (col. 3) in the household (Mother/Mother-in-law) decreases the labor supply directly. However, for women with a large number of children, having an older woman in the household (potentially providing care work) increases their labor market participation by 0.8% points. Women with older children who could provide care for younger children increased their hours of work by 5% points with an increase in the number of children (col. 6). These results suggest that teenagers and other married women provide help in childcare and enable greater FLFP. Another important finding from Table 6 is that the presence of other working adults in the family reduces female labor supply directly, but with an increasing number of children, the presence of working adults increases female working hours and earnings.

In Appendix 3, re-estimates Eq. (1) including dummies for the number of children (1 child, 2 children, and 3 or more children). In comparison with having no children, we analyze whether the effect of children on female’s labor supply differs by the levels of fertility. The figure shows that while the probability of working decreases with the first child, the effect is strongest for women who have three or more children. On the other hand, we found that women's earnings with one or two children is higher relative to women with no children. However, women's earnings go down only when a woman has three or more children.

Instrumental Variable Regression

To ameliorate endogeneity concerns, additionally we check for the consistency and validity of our Probit model using Instrumental Variable (IV) regression. We used son preference as an instrument for fertility. The son preference variable is defined as “1” if the woman respondent’s stated preference for desired number of sons was higher than desired number of daughters. The validity of the chosen instruments are tested using weak and under-identification tests.Footnote 1 Anderson-Canon LM statistic for under-identification shows that the model is identified at 1% level of significance. We also checked for weak identification using Cragg–Donald Wald F statistic. The value is compared with critical values specified by Stock and Yogo (2005). Since it is higher than the critical values of Stock-Yogo weak ID specifications, providing evidence that our instrument is strong.

The results for second stage IV regression are reported in Appendix 4 and are in keeping with our findings in Table 4. In other words, having additional children between the waves is negatively associated with women joining the work, while positively associated with their dropping out of the labor market.

Discussion and Conclusion

Female labor force participation in India continues to be low and the role of fertility and reproductive burden on labor market transitions remains unclear from previous empirical evidence. In this paper we have investigated the role of inter-temporal fertility changes on female labor force participation in India using the nationally representative IHDS panel dataset. To the best of our knowledge, we provide the first causal evidence on the role of inter-temporal within person changes in fertility on female labor market outcomes using a longitudinal dataset. Evidence from our descriptive analyses suggest that labor force participation for the same women has increased slightly over the period between 2004–2005 and 2011–2012. This trend has been observed in previous studies (Paweenawat & McNown, 2018; Tayal & Paul, 2021). The existing literature has also shown that women’s participation in paid work is higher as they become older and when their children are old enough—specifically at the tail end of reproductive span between 30 and 45 years. Similar evidence is also observed in our sample: as the panel of women in our sample have become older over time, the participation has gone up.

Our main analyses suggest that an increase in the number of children, especially young children, lower female labor force participation, and earnings. Pregnancy is also negatively associated with the earnings of women. Taking advantage of the panel design of the data, we further investigated the impact of fertility changes on transitions of women in and out of labor market. Our findings demonstrate that women who had additional children over the period 2004–2012 or became pregnant by the second wave of the survey are more likely to have exited out of the labor market, worked fewer hours, and earned less than their counterparts with no changes in their fertility levels. Furthermore, women who had more than three children in both rounds of the survey had a 3.5% points higher probability of exiting from the labor market.

The additional results suggest living in joint family or presence of other elder women in the family positively affects labor market participation for women with more number of children. However, strong social norms may be inhibiting the labor force participation of women with young children, particularly given the traditional role of mothers as caregivers to young children. Our results also indicate that the effects of children on labor market transitions are different for women based on caste status, economic status, and region. The motherhood penalty is highest for the women belonging to SC/ST caste groups and women with no formal education. With these findings, provisions for childcare like well-functioning Anganwadis in that village can moderate the labor supply by providing care to young children as have been found in the literature (Closser & Shekhawat, 2021).

By means of additional robustness checks, we further show that reproductive burden has heterogeneous implications for women from different regions and socio-economic grounds. Heterogeneous effect analyses by caste, economic, educational status, and region show that the probability of dropping out of the labor market due to fertility changes varies by region and is greater for non-poor and primary to secondary schooling women and those from socially disadvantaged castes. However, reproductive burden influences labor market outcomes among women from other socio-economic categories as well. Our findings are also robust to test of endogeneity concerns using IV regression.

In conclusion, we advance that in present labor market environment, a higher reproductive burden is negatively associated with labor market outcomes for women in India. This study indicates that women’s entry or exit from the labor market are sensitive to changes in the reproductive burden. Despite the fact that our findings are reliable across the multiple robustness checks, it has one limitation. We fail to analyze and report the exact supply-side barriers (labor market conditions) that force women to exit from the employment during pregnancy and motherhood. Thus, further studies are required to identify the specific labor market conditions that are unconducive and forcing them to exit out of the job during pregnancy and maternity period.

Nevertheless, interpretation of our findings in the context of known labor market conditions laydown in policy documents uncover that they are not very conducive for a large section of women to continue in the job during maternity period. Although India’s Maternity (Amendment) Bill 2017 has increased the right to paid maternity leave for working women from 12 to 26 weeks, it only benefits a small proportion of working women in formal jobs. Approximately 84% of the female labor force in India is in the informal sector with no access to maternity leave provisions (De et al. 2019; Williams, 2017). Child care provisions like Anganwadis can help in moderating female labor supply but the success of the same is dependent upon the good implementation (Maity, 2016). Such provisions may also be implemented in urban areas where declining labor supply has been a concern among economists. The question of paternity leaves needs to be addressed in Indian labor markets to bring gender balance in the responsibility of child care at the households. Therefore, India needs to design better ‘work-family’ policies to reconcile the tension between children’s caring needs and wage employment for women.

Notes

Only one instrument, so over identification cannot be tested.

References

Adair, L., Guilkey, D., Bisgrove, E., & Gultiano, S. (2002). Effect of childbearing on Filipino women’s work hours and earnings. Journal of Population Economics, 15(4), 625–645. https://doi.org/10.1007/s001480100101

Afridi, F., Dinkelman, T., & Mahajan, K. (2017). Why are fewer married women joining the workforce in rural India? A decomposition analysis over two decades. Journal of Population Economics, 31(3), 783–818.

Afridi, F., Bishnu, M., & Mahajan, K. (2019). What determines women’s labor supply? The role of home productivity and social norms. IZA Discussion Paper Series no. 12666.

Agüero, J. M., & Marks, M. S. (2011). Motherhood and female labor supply in the developing world evidence from infertility shocks. Journal of Human Resources, 46(4), 800–826.

Ajefu, J. B. (2019). Does having children affect women’s entrepreneurship decision? Evidence from Nigeria. Review of Economics of the Household, 17(3), 843–860. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11150-019-09453-2

Ashenfelter, O., & Heckman, J. (1974). The estimation of income and substitution effects in a model of family labor supply. Econometrica, 42(1), 73–85.

Azimi, E. (2015). The effect of children on female labor force participation in urban Iran. IZA Journal of Labor & Development, 4(1), 1–11.

Baranowska-Rataj, A., & Matysiak, A. (2022). Family size and men’s labor market outcomes: do social beliefs about men’s roles in the family matter? Feminist Economics, 20, 1–26.

Becker, G. S. (1960). An economic analysis of fertility Demographic and economic change in developed countries (pp. 209–240): Columbia University Press.

Bernardi, F. (2001). The employment behaviour of married women in Italy. Careers of Couples in Contemporary Societies, 12, 121–145.

Bhattacharyya, A., & Haldar, S. K. (2020). Does U feminisation work in female labor force participation rate? India: A case study. The Indian Journal of Labor Economics, 15, 1–18.

Bloom, D. E., Canning, D., Fink, G., & Finlay, J. E. (2009). Fertility, female labor force participation, and the demographic dividend. Journal of Economic Growth, 14(2), 79–101. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10887-009-9039-9

Bongaarts, J., Blanc, A. K., & McCarthy, K. J. (2019). The links between women’s employment and children at home: Variations in low- and middle-income countries by world region. Population Studies, 73(2), 149–163. https://doi.org/10.1080/00324728.2019.1581896

Budig, M. J., & England, P. (2001). The wage penalty for motherhood. American Sociological Review, 66(2), 204–225. https://doi.org/10.2307/2657415

Chatterjee, E., Desai, S., & Vanneman, R. (2018). Indian paradox: Rising education, declining women’s employment. Demographic Research, 38, 855–878. https://doi.org/10.4054/DemRes.2018.38.31

Chatterjee, U., Murgai, R., & Rama, M. (2015). Job opportunities along the rural-urban gradation and female labor force participation in India. World Bank Policy Research Working Paper 7412, (7412). The World Bank

Chaudhary, R., & Verick, S. (2014). Female labor force participation in India and beyond. ILO Asia-Pacific Working Paper Series. New Delhi.

Chun, H., & Oh, J. (2002). An instrumental variable estimate of the effect of fertility on the labour force participation of married women. Applied Economics Letters, 9(10), 631–634.

Closser, S., & Shekhawat, S. S. (2021). The family context of ASHA and Anganwadi work in rural Rajasthan: Gender and labour in CHW programmes. Global Public Health, 4, 1–13.

Correll, S. J., Benard, S., & Paik, I. (2007). Getting a job: Is there a motherhood penalty? American Journal of Sociology, 112(5), 1297–1339. https://doi.org/10.1086/511799

Cruces, G., & Galiani, S. (2007). Fertility and female labor supply in Latin America: New causal evidence. Labor Economics, 14(3), 565–573. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.labeco.2005.10.006

Cáceres-Delpiano, J. (2012). Can we still learn something from the relationship between fertility and mother’s employment? Evidence from Developing Countries. Demography, 49(1), 151–174. https://doi.org/10.1007/s13524-011-0076-6

Das, S., Chandra, S. J., Kochhar, K., & Kumar, N. (2015a). Women workers in India: Why so few among so many? IMF Working Paper, (WP/15/55).

Das, S., Jain-Chandra, S., Kochhar, K., & Kumar, N. (2015b). Women workers in India: why so few among so many? IMF Working Paper, (15–55). International Monetary Fund.

Das, M. B., & Zumbyte, I. (2017). The motherhood penalty and female employment in urban India (No. 8004). The World Bank.

De, I., Kumar, M., & Shylendra, H. S. (2019). Work conditions and employment for women in slums. Economic & Political Weekly, 54(21), 37.

Desai, S., & Joshi, O. (2019). The paradox of declining female work participation in an era of economic growth. The Indian Journal of Labor Economics, 62(1), 55–71.

Desai, S. (2018). Do public works programs increase women’s economic empowerment: Evidence from rural India. Indian Human Development Survey Working Paper.

Desai, S. B., Dubey, A., Joshi, B. L., Sen, M., Shariff, A., & Vanneman, R. (2010). Human development in India. Oxford University.

Deshpande, A. (2011). The grammar of caste: Economic discrimination in contemporary India. Oxford University Press.

Deshpande, A., Goel, D., & Khanna, S. (2018). Bad karma or discrimination? Male–female wage gaps among salaried workers in India. World Development, 102, 331–344.

Dhanaraj, S., & Mahambare, V. (2019). Family structure, education and women’s employment in rural India. World Development, 115, 17–29.

Drèze, J., & Sen, A. (1997). Indian development: Selected regional perspectives. Oxford University Press.

Drobnič, S. (2000). The effects of children on married and lone mothers’ employment in the United States and (West) Germany. European Sociological Review, 16(2), 137–157.

Dyson, T., & Moore, M. (1983). On kinship structure, female autonomy, and demographic behavior in India. Population and Development Review, 9(1), 35–60.

Ebenstein, A. (2009). When is the local average treatment close to the average? Evidence from fertility and labor supply. Journal of Human Resources, 44(4), 955–975.

Felmlee, D. H. (1993). The dynamic interdependence of women′ s employment and fertility. Social Science Research, 22(4), 333–360.

Francavilla, F., & Giannelli, G. C. (2011). Does family planning help the employment of women? The case of India. Journal of Asian Economics, 22(5), 412–426.

Gaddis, I., & Klasen, S. (2014). Economic development, structural change, and women’s labor force participation. Journal of Population Economics, 27(3), 639–681.

Giannelli, G. C. (1996). Women’s transitions in the labour market: A competing risks analysis on German panel data. Journal of Population Economics, 9(3), 287–300.

Goli, S. (2016). Eliminating child marriages in India: Progress and prospects. Child Rights Focus-Action Aid. Retrieved from https://www.actionaidindia.org/publications/eliminating-child-marriage-in-india/

Goryakin, Y., Rocco, L., Suhrcke, M., Roberts, B., & McKee, M. (2014). The effect of health on labor supply in nine former Soviet Union countries. The European Journal of Health Economics, 15(1), 57–68.

Grimm, M., & Bonneuil, N. (2001). Labour market participation of French women over the life cycle, 1935–1990. European Journal of Population/revue Européenne De Démographie, 17(3), 235–260.

Grunow, D., Hofmeister, H., & Buchholz, S. (2006). Late 20th-century persistence and decline of the female homemaker in Germany and the United States. International Sociology, 21(1), 101–131.

He, X., & Zhu, R. (2016). Fertility and female labour force participation: Causal evidence from urban China. The Manchester School, 84(5), 664–674.

Heath, R. (2017). Fertility at work: Children and women’s labor market outcomes in urban Ghana. Journal of Development Economics, 126, 190–214. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jdeveco.2016.11.003

Hirway, I., & Jose, S. (2011). Understanding women’s work using time-use statistics: The case of India. Feminist Economics, 17(4), 67–92. https://doi.org/10.1080/13545701.2011.622289

Hofmeister, H. (2006). Women’s employment transitions and mobility in the United States: 1968 to 1991. Globalization, Uncertainty and Women’s Careers: An InternationalComparison, 302

James, K. S., & Goli, S. (2016). Demographic changes in India: Is the country prepared for the challenge. Brown Journal of World Affairs, 23, 169.

Kambhampati, U. S. (2009). Child schooling and work decisions in India: The role of household and regional gender equity. Feminist Economics, 15(4), 77–112. https://doi.org/10.1080/13545700903153997

Kambhampati, U. S., & Rajan, R. (2008). The ‘nowhere’children: Patriarchy and the role of girls in India’s rural economy. The Journal of Development Studies, 44(9), 1309–1341.

Kapsos, S., Bourmpoula, E., & Silberman, A. (2014). Why is female labor force participation declining so sharply in India? ILO Research Paper No. 10.

Kishor, S. (1993). “ May God give sons to all”: Gender and child mortality in India. American Sociological Review, 58(2), 247–265.

Klasen, S., & Pieters, J. (2015). What explains the stagnation of female labor force participation in urban India? The World Bank Economic Review, 29(3), 449–478. https://doi.org/10.1093/wber/lhv003

Kuhn, S., Milasi, S., & Yoon, S. (2018). World employment social outlook: Trends 2018. ILO.

Lahoti, R., & Swaminathan, H. (2016). Economic development and female labor force participation in India. Feminist Economics, 22(2), 168–195. https://doi.org/10.1080/13545701.2015.1066022

Leth-Sørensen, S., & Rohwer, G. (2001). Work careers of married women in Denmark. Careers of Couples in Contemporary Societies, 14, 261–279.

MOHFW. (2019). Report of the Technical Group on Population Projections. (2019). Population Projections For India And States 2011–2036, National Commission on Population, Ministry Of Health & Family Welfare.

Maity, B. (2016). Interstate differences in the performance of “Anganwadi” centres under ICDS scheme. Economic and Political Weekly, 51(51), 59–66.

Matysiak, A., & Vignoli, D. (2008). Fertility and women’s employment: A meta analysis. European Journal of Population/revue Européenne De Démographie, 24(4), 158–384.

Mincer, J. (1962). Labor force participation of married women: A study of labor supply Aspects of labor economics (pp. 63–105): Princeton University Press.

NSSO. (2014). Employment and unemployment situation in India (NSS 68th round). NSS Report No. 554 (681101).

Paweenawat, S. W., & McNown, R. (2018). A synthetic cohort analysis of female labour supply: The case of Thailand. Applied Economics, 50(5), 527–544.

Pradhan, B. K., Singh, S. K., & Mitra, A. (2015). Female labor supply in a developing economy: A tale from a primary survey. Journal of International Development, 27(1), 99–111.

Raeymaeckers, P., Dewilde, C., Snoeckx, L., & Mortelmans, D. (2008). The influence of formal and informal support systems on the labor supply of divorced mothers. European Societies, 10(3), 453–477.

Rammohan, A., & Vu, P. (2018). Gender inequality in education and kinship norms in India. Feminist Economics, 24(1), 142–167.

Rammohan, A., & Whelan, S. (2005). Child care and female employment decisions. Australian Journal of Labor Economics, 8(2), 203–225.

Sarkar, S., Sahoo, S., & Klasen, S. (2019). Employment transitions of women in India: A panel analysis. World Development, 115, 291–309.

Selwaness, I., & Krafft, C. (2020). The dynamics of family formation and women’s work: what facilitates and hinders female employment in the Middle East and North Africa? Population Research and Policy Review, 14, 1–55.

Sengupta, A., & Das, P. (2014). Gender wage discrimination across social and religious groups in India. Economic and Political Weekly, 49(21), 71.

Sorsa, P., Mares, J., Didier, M., Guimaraes, C., Rabate, M., Tang, G., & Tuske, A. (2015). Determinants of the low female labor force participation in India. OECD Economics Department Working Papers, (1207).

Stock, J. H., & Yogo, M. (2005). Testing for weak instruments in linear IV regression. In D. W. K. Andrews & J. H. Stock (Eds.), Identification and Inference for Econometric Models: Essays in Honor of Thomas Rothenberg (pp. 80–108). Cambridge University Press.

Sundaram, A., & Vanneman, R. (2008). Gender differentials in literacy in India: The intriguing relationship with women’s labor force participation. World Development, 36(1), 128–143.

Tam, H. (2011). U-shaped female labor participation with economic development: Some panel data evidence. Economics Letters, 110(2), 140–142.

Tayal, D., & Paul, S. (2021). Labour Force Participation Rate of Women in Urban India: An Age-Cohort-Wise Analysis. The Indian Journal of Labour Economics, 64(3), 565–593.

Thomas, J. J. (2012). India’s labor market during the 2000s: Surveying the changes. Economic and Political Weekly, 47(51), 39–51.

Verick, S. (2018). "Female labor force participation and development." IZA World of Labor .

Williams, C. C. (2017). Reclassifying economies by the degree and intensity of informalization: The implications for India. In Critical perspectives on work and employment in globalizing India (pp. 113–129). Springer, Singapore.

Yount, K. M., Crandall, A., & Cheong, Y. F. (2018). Women’s age at first marriage and long-term economic empowerment in Egypt. World Development, 102, 124–134.

Funding

Open Access funding enabled and organized by CAUL and its Member Institutions.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Additional information

Publisher's Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Supplementary Information

Below is the link to the electronic supplementary material.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License, which permits use, sharing, adaptation, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if changes were made. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article's Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article's Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Tiwari, C., Goli, S. & Rammohan, A. Reproductive Burden and Its Impact on Female Labor Market Outcomes in India: Evidence from Longitudinal Analyses. Popul Res Policy Rev 41, 2493–2529 (2022). https://doi.org/10.1007/s11113-022-09730-6

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s11113-022-09730-6