The Gastric Network: How the stomach and the brain work together at rest

The brain is always active – even when it is at rest, it receives a continuous stream of information from other areas of the body. From gut feelings to heartbeats, this information is constantly monitored to maintain a state of physiological equilibrium known as homeostasis. Signals from the body, including the stomach, also influence a variety of mental processes and complex human behaviours (Critchley and Harrison, 2013; Herbert and Pollatos, 2012; Porciello et al., 2018). Although the anatomy of the homeostatic neural pathway is relatively well known (Craig, 2003), its physiology is less well understood.

During periods of wakeful rest, our brain generates its own spontaneous and synchronised activity within different groups of brain regions (known as resting-state networks). On the other hand, specialised cells in the stomach produce a slow, continuous pattern of electrical impulses that set the pace of stomach contractions during digestion. But the stomach also generates these signals when it is empty, which suggests that they may have another purpose. Now, in eLife, Ignacio Rebollo of the PSL Research University and co-workers – Anne-Dominique Devauchelle, Benoît Béranger, and Catherine Tallon-Baudry – report how they have combined two techniques, functional magnetic resonance imaging and electrogastrography, to shed new light on the interactions between the brain and the stomach (Rebollo et al., 2018).

Rebollo et al. placed electrodes on the abdomen of volunteers as they lay inside a brain scanner and analysed the coupling between the signals from the stomach and the brain using a method called phase-locking value analysis. The researchers discovered a new resting-state network – the gastric network – which fired in synchrony with the rhythm of the stomach (Figure 1A). Furthermore, the various brain regions within this network showed a delayed functional connectivity between each other.

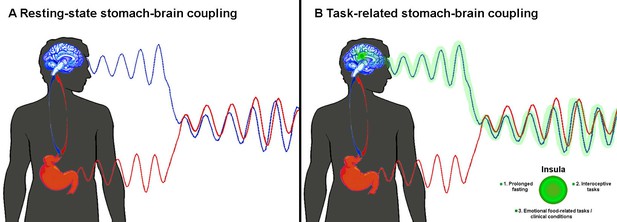

Coupling between the activity of the brain and the stomach.

(A) When the body is at rest, Rebollo et al. found that the blood flow in the brain (as measured by functional magnetic resonance imaging; blue wave) and the electrical activity in the stomach (as measured by electrogastrography; red wave) are in delayed sync with each other (Rebollo et al., 2018). (B) Rebollo et al. discovered that the insula (green) was only marginally coupled with the stomach. We think that the activity of this region (green wave) will be more synchronous with that of the stomach when certain conditions are met (see main text).

Although the role of the gastric network remains unknown, Rebollo et al. reasoned that some of the brain regions within the network map information about vision, touch and movement in bodily coordinates. Thus, they advanced the tantalising hypothesis that this network coordinates different ‘body-centred maps’ in the brain. According to this, a region in the brain known as the insula should be strongly involved in the gastric network: this region receives direct input from the internal organs (e.g. stomach, intestine), which is integrated to create a coherent representation of the whole body (Critchley and Harrison, 2013; Craig, 2009). However, Rebollo et al. found that the insula was only marginally synchronised to the rhythm of the stomach.

Thus, we suggest that the gastric network may rather act as a homeostatic regulator of food intake. Indeed, it neatly overlaps with areas processing information from the face, mouth and hands, and with three brain regions activated by tongue- or hand-related actions (Amiez and Petrides, 2014). We speculate that the insula would play a bigger role in the network if at least one of the following applied: the fasting happened over a longer period; the participants had to complete tasks that made them focus on their own gut feelings (interoceptive tasks); the participants attached a higher emotional value to food, either as a source of reward or disgust, as happens in people with eating disorders such as anorexia or bulimia nervosa (Figure 1B).

Due to the limitations of the phase-locking method (Lachaux et al., 1999), it remains unclear if the rhythmic interaction between the stomach and the brain is one-directional or two-directional. Clarifying this issue and measuring the stomach-brain coupling during conditions in which the body is far from homeostasis, and during interoceptive or emotional tasks, may help to shed light on the true functional role of the gastric network. We believe that the findings of Rebollo et al. not only open new avenues to improving our understanding of the resting-state activity, but also fire up an exciting debate on how signals from the enteric nervous system in the gut could shape the brain.

References

-

Interoception: the sense of the physiological condition of the bodyCurrent Opinion in Neurobiology 13:500–505.https://doi.org/10.1016/S0959-4388(03)00090-4

-

How do you feel--now? The anterior insula and human awarenessNature Reviews Neuroscience 10:59–70.https://doi.org/10.1038/nrn2555

-

The body in the mind: on the relationship between interoception and embodimentTopics in Cognitive Science 4:692–704.https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1756-8765.2012.01189.x

-

Measuring phase synchrony in brain signalsHuman Brain Mapping 8:194–208.https://doi.org/10.1002/(SICI)1097-0193(1999)8:4<194::AID-HBM4>3.0.CO;2-C

-

The ’Enfacement’ illusion: a window on the plasticity of the selfCortex S0010-9452(18)30020-0.https://doi.org/10.1016/j.cortex.2018.01.007

Article and author information

Author details

Publication history

- Version of Record published: May 4, 2018 (version 1)

Copyright

© 2018, Porciello et al.

This article is distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution License, which permits unrestricted use and redistribution provided that the original author and source are credited.

Metrics

-

- 5,081

- views

-

- 332

- downloads

-

- 8

- citations

Views, downloads and citations are aggregated across all versions of this paper published by eLife.

Download links

Downloads (link to download the article as PDF)

Open citations (links to open the citations from this article in various online reference manager services)

Cite this article (links to download the citations from this article in formats compatible with various reference manager tools)

Further reading

-

- Neuroscience

Nociceptive sensory neurons convey pain-related signals to the CNS using action potentials. Loss-of-function mutations in the voltage-gated sodium channel NaV1.7 cause insensitivity to pain (presumably by reducing nociceptor excitability) but clinical trials seeking to treat pain by inhibiting NaV1.7 pharmacologically have struggled. This may reflect the variable contribution of NaV1.7 to nociceptor excitability. Contrary to claims that NaV1.7 is necessary for nociceptors to initiate action potentials, we show that nociceptors can achieve similar excitability using different combinations of NaV1.3, NaV1.7, and NaV1.8. Selectively blocking one of those NaV subtypes reduces nociceptor excitability only if the other subtypes are weakly expressed. For example, excitability relies on NaV1.8 in acutely dissociated nociceptors but responsibility shifts to NaV1.7 and NaV1.3 by the fourth day in culture. A similar shift in NaV dependence occurs in vivo after inflammation, impacting ability of the NaV1.7-selective inhibitor PF-05089771 to reduce pain in behavioral tests. Flexible use of different NaV subtypes exemplifies degeneracy – achieving similar function using different components – and compromises reliable modulation of nociceptor excitability by subtype-selective inhibitors. Identifying the dominant NaV subtype to predict drug efficacy is not trivial. Degeneracy at the cellular level must be considered when choosing drug targets at the molecular level.

-

- Neuroscience

Despite substantial progress in mapping the trajectory of network plasticity resulting from focal ischemic stroke, the extent and nature of changes in neuronal excitability and activity within the peri-infarct cortex of mice remains poorly defined. Most of the available data have been acquired from anesthetized animals, acute tissue slices, or infer changes in excitability from immunoassays on extracted tissue, and thus may not reflect cortical activity dynamics in the intact cortex of an awake animal. Here, in vivo two-photon calcium imaging in awake, behaving mice was used to longitudinally track cortical activity, network functional connectivity, and neural assembly architecture for 2 months following photothrombotic stroke targeting the forelimb somatosensory cortex. Sensorimotor recovery was tracked over the weeks following stroke, allowing us to relate network changes to behavior. Our data revealed spatially restricted but long-lasting alterations in somatosensory neural network function and connectivity. Specifically, we demonstrate significant and long-lasting disruptions in neural assembly architecture concurrent with a deficit in functional connectivity between individual neurons. Reductions in neuronal spiking in peri-infarct cortex were transient but predictive of impairment in skilled locomotion measured in the tapered beam task. Notably, altered neural networks were highly localized, with assembly architecture and neural connectivity relatively unaltered a short distance from the peri-infarct cortex, even in regions within ‘remapped’ forelimb functional representations identified using mesoscale imaging with anaesthetized preparations 8 weeks after stroke. Thus, using longitudinal two-photon microscopy in awake animals, these data show a complex spatiotemporal relationship between peri-infarct neuronal network function and behavioral recovery. Moreover, the data highlight an apparent disconnect between dramatic functional remapping identified using strong sensory stimulation in anaesthetized mice compared to more subtle and spatially restricted changes in individual neuron and local network function in awake mice during stroke recovery.