Introduction

For decades, African countries have mainly depended on overseas development assistance for developmental purposes. This was partly due to the colonial project that made the colonies subjects of the empire. Secondly, several countries in Africa became indebted to financial institutions as a result of structural adjustment programmes that were driven mainly by the World Bank and the International Monetary Fund (IMF). Zimbabwe, like other African countries and those of the global south, was for many decades a major recipient of foreign aid in order to improve the livelihoods of people and to drive the nation’s development. Since independence, literature abounds on the extent to which the country depended on various forms of aid (see Moyo, 1995; Chikowore, 2010; Bird & Busse, 2007; Gurukume, 2012). During the liberation struggle, various countries also supported Zimbabwe to free itself from Britain. The help came in cash and in kind. After independence, the country received both bilateral and multilateral support especially from the industrialised nations until it was put under sanctions after 2000. Still, help was given to the country through selected bilateral, multilateral and philanthropic channels. This pattern is not different in other countries and regions of the world where aid is seen as important in advancing the development of poorer nations.

Given the above context, this article seeks to highlight three issues:

- Firstly, it outlines the aid patterns in Zimbabwe – showing the gradual decline of aid and how this has been a global phenomenon that was recently exacerbated by the COVID-19 pandemic. In the context of Zimbabwe, the ongoing economic crisis and political stalemate as well as sanctions have further exacerbated the decline of aid to the country.

- Secondly, the article argues that even if aid was available, it does not necessarily equate to development given that it comes with conditionalities.

- Thirdly, the article argues for alternative ways of approaching development. The case of Zimbabwe is illustrative. The country has little aid and limited state resources, yet the country has not collapsed. It has been more than twenty years since the country faced an economic and political meltdown. What then are some of the new frontiers of support and survival that citizens have drawn support from? How influential are these new forms of solidarity in advancing a more inclusive society and in the advancement of true development?

Aid and Development

Despite the levels of aid – which amounts to over USD1 trillion in assistance since the 1970s, sub-Saharan Africa is still floundering in a cycle of disease and poverty when compared to other regions of the global south (Moyo, 2009). Citizens of Africa are worse off – they have remained poorer, and development has slowed down over time. When aid flows to Africa were at their peak, poverty rate rose from 11% to 66% (Moyo, 2009). Africa’s per capita income continues to fall, life expectancy is stagnated, and, in some instances, it has regressed. The proportion of poor inhabitants in Africa has grown, making Africa the only continent where poverty has grown so drastically (Moyo & Mafuso, 2017). In Asia, the poverty rate dropped from 73.6% in 1965 to less than 10% in 2014 (WIDER, 2020) based on a US$3.20 per day poverty line, while in Latin America using a poverty line of US$4 a day, the region’s population living in poverty fell from 45 to 25 per cent between 2000 and 2014 (Levy, 2016).

For scholars such as Dambisa Moyo (2009), aid has not been transformative to Africa. According to Moyo (2009), the continent’s ‘cycle of disfunction’ is linked to or has its roots in aid. Moyo and Mafuso (2017) highlight that aid effectiveness can only be seen if people’s livelihoods are changed for the better. Dambisa Moyo (2009) has further challenged many assumptions about aid and argued that “recipients of this aid are worse off” (p. 17).

The debate around the usefulness or effectiveness of foreign aid has often pitted proponents of aid against those who are critical of aid. For instance, economics professor, William Easterly (2009) has also been an opponent arguing that poverty results from an absence of economic and political rights, and that only the restoration of these will address the issue (Melesse, 2021). Melesse (2021) notes that criticism of aid can be traced close to 50 years ago. Peter Bauer was a strong critic of government-to-government aid. His argument was that this aid was neither necessary nor efficient and that in fact what it did do was to promote government power, destroy economic incentives while diminishing civic initiatives and dynamism (Melesse, 2021). Broadly, the aid critics highlight how official aid creates “dependency, fosters corruption, encourages currency overvaluation, and doesn’t allow countries to take advantage of the opportunities provided by the global economy” (Melesse, 2021, “An old debate”, para. 4).

The increasing critique of external aid as a catalyst for development raises the need to examine other ways through which countries in the South can respond to the needs of their citizens. There is no doubt that some forms of aid will remain useful as it has been previously. Examples include quick humanitarian responses to pandemics and catalytic finances such as that provided by philanthropic sources. However, as more and more criticism piles up on aid and new developments take place in the global North such as the reduction of their contributions, there is need to look for resources in the domestic markets for countries in the south. Ghana, for example, already introduced a ‘beyond aid’ policy – the Ghana Beyond Aid Charter and Strategy Document (Government of Ghana, 2019) that seeks to have Ghana benefit from trade relations than from aid relations. The principal factor behind such shifts has to do with the fact that aid has failed to provide any significant development in the continent so far. Africa cannot depend on aid only to try and advance its development and ultimately improve the livelihoods of its citizens, the solutions and resourcing to address the development challenges of the continent must come from within or from other sources other than aid. Philanthropy in its different forms is one such source. Several governments in Africa have now established frameworks to engage philanthropy. These range from philanthropy strategies such as the case of the government of Rwanda to Philanthropy Departments or departments in government that are responsible for philanthropy, for example in Liberia, South Africa and Kenya among others.

Foreign Aid

Ajayi (2000) has defined foreign aid as a form of assistance by a government or by financial institutions to other needy countries. This assistance can either be in cash or kind. Another definition of foreign aid put forward by Lancaster (2007) is that it is a voluntary transfer of public resources, from one government to another independent government, or a Non-Governmental Organization (NGO), or to an international organization (such as the World Bank or The United Nations Development Program (UNDP)) with at least a 25% grant element, with the goal to improve the human conditions in the country receiving the aid. The transfer of resources is often from richer countries in the global north to the poorer countries of the global south.

There are three distinct types of aid:

- Humanitarian or emergency aid

- Charity based aid

- Systematic aid (aid payments made directly to governments through bi-lateral or multi-lateral agencies, loans, and grants)

Prior to World War II (WWII), the early objective of foreign aid was mostly for political and military support. At the end of WWII, with the devastation caused by the war, aid was used to provide immediate disaster relief to help Western European economies rebuild. An example of this was the Marshal Plan. In the post-colonial period in the 1960s and 1970s, aid was used to help to advance the economies of newly independent countries and as a means to advance development. By the 1990s most countries changed their primary objectives of giving aid to the improvement of the lives of the poor (Sogge, 2002). Sogge (2002) has identified three basic objectives of the World Bank and Organisation for Economic Co-operation and Development (OECD) countries in giving aid. These are:

- Reducing material poverty, chiefly through economic growth, but also through the provision of public infrastructure and basic social services.

- Promoting good governance, chiefly in effective, honest and democratically ac- countable institutions to manage the economy and the legal order, but also in the promotion of civil and political rights.

- Reversing the negative environmental trends.

Foreign aid has been seen as a bridge to counter the disparities that exist between developed and developing countries and are largely reflected in the different living standards across countries. According to Tarp (2009), the major disparities that exist are around the following four areas:

- Productive capacity – poor countries do not produce very much.

- Lack of physical capital.

- Lack of human capital.

- Lack of technology and functioning institutions.

Foreign aid’s main role now is focused on improving living standards significantly so that poor countries can produce more. It is seen as the vehicle that will promote economic growth and foster development. Foreign aid has therefore been projected and seen as a tool for modernization. This, however, is still debatable for the African continent. Foreign aid has yet to deliver an improved “modern” Africa. The continent has made some mild attempts at development and modernisation but when compared to Asia and Latin America, it remains woefully behind in terms of infrastructure and technological advancements.

Modernization Theory and Foreign Aid

If foreign aid is seen as a tool of modernization, there is a significant link between the modernization theory of development and foreign aid. The modernization theory of development came about in the 1940s. The aim of this theory was to firstly, explain why poor countries were failing to develop by highlighting the economic and cultural conditions that were preventing their growth; secondly to advance the notion that the solution to poverty lay in capitalism and the adoption of western values and culture; and thirdly to stress that countries that wanted to develop, therefore, had to do away with traditional values and culture and take on those of the global north if they wanted to advance.

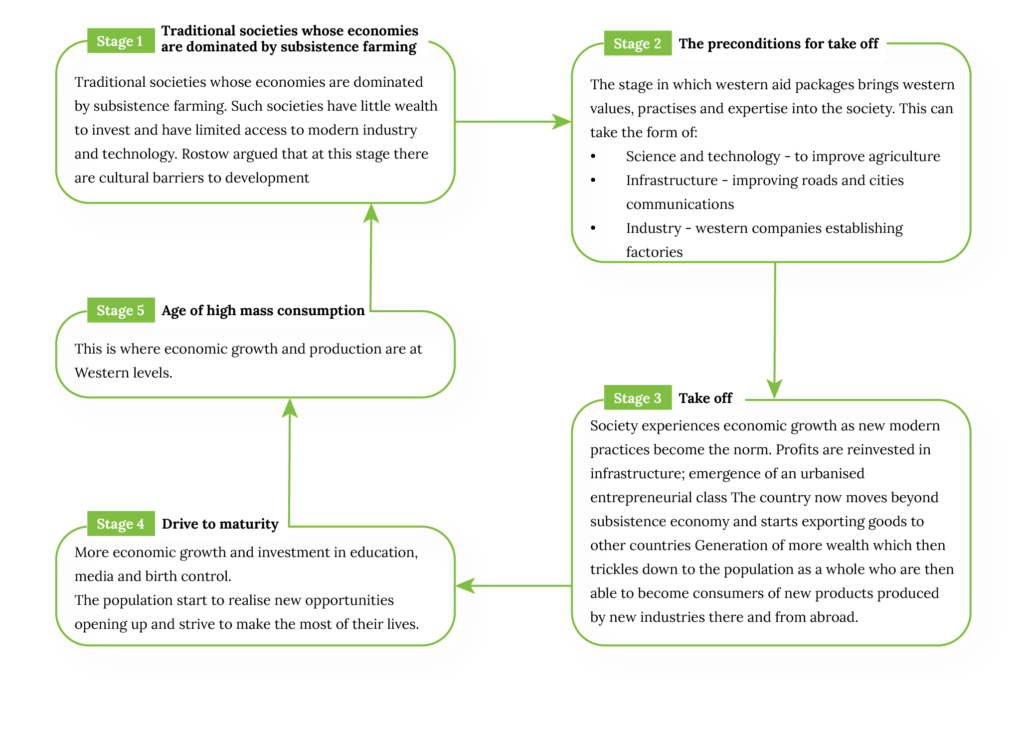

How do countries then modernize? The answer lies in a key concept within this theory put forward by economist Walt Rostow in 1960 – which outlines the five (5) stages a country must go through to become modern (see Figure 1).

Countries start off as ‘traditional’ societies and ultimately go through various stages to reach the 5th stage which he termed ‘The age of high mass consumption’. At this stage countries undergoing development, will be expected to have the productive capacity and economic growth levels comparative to western countries. These stages are ones that developed countries have gone through and the expectation is that developing countries must therefore follow in the same footsteps if they are to develop. As discussed earlier, this has not been the case with African countries due to political, economic and geo-political factors that have sought to keep African countries indebted to the North.

Challenges with Modernisation Theory and Foreign Aid

There have been major criticisms of the modernisation theory. Central to them is the one-size fits all approach that it adopts. The theory fails to take into account contextual differences and nuances present from one country to another and makes all developing countries seem homogenous. The theory does not speak on or reflect upon some of the problems of modernization and the challenges of inequality in developing countries. The model assumes that countries need the help of outside forces. The premise is that experts and money coming in from the outside, are parachuted in, and with their injection bring about development. This notion downgrades and completely fails to recognize the role of local knowledge and initiatives and can be seen as demeaning and dehumanising for local communities and actors. Galeano (1992) argues that minds become colonised with the idea that they are dependent on outside forces. The theory fails to also take into consideration underlying internal challenges such as corruption which also prevents aid of any kind from doing good. Aid is often siphoned off by corrupt elites and government officials rather than getting to the projects it was earmarked for. This means that aid creates more inequality and enables elites to maintain power. There are also ecological limits to the growth of some of the projects proposed to modernise a country. The extraction of primary resources for initiatives such as mining and forestry has led to the destruction of the environment as well as, at times, the forcible removal of people from their land with little to no compensation. A closer look at the case of Zimbabwe helps to illuminate the arguments advanced above.

History of Foreign Aid in Zimbabwe

Independence for Zimbabwe in 1980 coincided with the 1980 United Nations Decade for Development in the Third World and with it an increase in development assistance. In addition, individual states also sought to support the new government. Both the International Monetary Fund (IMF) and World Bank have been foreign aid donors to Zimbabwe, with the World Bank being the largest donor to Zimbabwe since 1980. Between 1980 and 1981 Zimbabwe received 14 bank loans and four (4) International Development Association (IDA) credits amounting to US$657 million (Dashwood, 2000). During that period, US$51 million went towards promoting agricultural development in the communal areas, US$136 million to the rehabilitation and expansion of exports of the manufacturing sector, US$150 million to the energy sector, US$141 million to the transport sector, as well to the other smaller projects, such as urban development and support to small scale enterprise (Dashwood, 2000, p. 68). World Bank Group (WBG) assistance to Zimbabwe totalled $1.6 billion between 1980 and 2000 (World Bank, 2022).

Since the year 2000, the World Bank suspended its direct lending to Zimbabwe because of non-payment of arrears. Support that has come through from the World Bank since 2000 has been sector-specific and limited in terms of amount. A key fund has been the Zimbabwe Reconstruction Fund in place since 2014, which has since inception received US$52 million from development partners (World Bank, 2021). The IMF holds a similar position. In September 2001, the country was declared ineligible to use the general resources of the IMF and to borrow resources. As of September 2022, the IMF’s position was that it was “precluded from providing financial support to Zimbabwe due to unsustainable debt and official external arrears” (Press Release No.22/310: IMF Staff Concludes Staff Visit to Zimbabwe, para. 5). The fund currently provides Zimbabwe with technical assistance on economic governance, financial sector reforms and microeconomic statistics.

Zimbabwe has received comparatively high levels of foreign aid for a long period peaking in the 1990s – during the period of the Economic Structural Adjustment Program (ESAP). Aid levels from the World Bank and IMF started to decline in 1996 and direct aid or lending from these entities ceased in 2000 at the height of Zimbabwe’s fast-track land reform program; a worsening economic crisis and political impasse brought about because of the land reform program. The land reform program caused declared and undeclared sanctions against the country by multi-lateral financial institutions and foreign governments. The country was no longer eligible to access financial and technical assistance. It also led to the suspension of voting rights and the suspension of balance of payments. This meant that after 2000 Zimbabwe was isolated from international capital and this precipitated the economic crisis in that country.

However, even at its peak levels of receiving aid, especially in the early 1990s with the introduction of ESAP, there was no significant shift or improvement in the livelihoods of the majority of citizens. In 1998, the Central Statistics Office noted that the incidence of poverty in Zimbabwe increased from 40.4% in 1990 – 91 to 63.3% by 1995 – 96. In addition, the government slowly started to lose policy autonomy as the structural adjustments programs were conditional and if the government was to continue to get foreign aid, there was a requirement to cut back on what the IMF and World Bank considered to be unnecessary spending; open up the economy through the removal of measures to protect local manufacturers and adoption of more liberal economic policies and less focus on social policies and measures. ESAP worsened the economic crisis in Zimbabwe (characterised by a shrinking formal economy, mass retrenchments, shrinking tax base, and increased levels of formalisation and lack of service delivery) and deepened external dependency on foreign aid. In addition, the conditions attached to such multilateral aid are the principal cause of abject poverty. This situation was not only unique to Zimbabwe but to many African countries that adopted structural adjustment programs at the behest of the IMF and World Bank.

The situation in Zimbabwe post-2000 has progressively worsened and the economic crises became more prolonged. The political isolation of the country by the west continues and access to substantive financial aid from the west remains restricted. For all intents and purposes in such a scenario, the expectation would have been for the country to degenerate into chaos. However, Murisa (2022) highlights that “many have sought to understand why despite years of economic crises Zimbabwe has not degenerated into a much deeper political crisis or chaos” (p. 7). So what then has held things together? One of the reasons has been the growth in funding inflows from China and Russia in attempts to increase their global influence and break the monopoly of western aid. According to Sun (2014) most of the financing by China in Africa “falls under the category of development finance and not aid” (What constitutes China’s aid?, para. 2). With the drop and conditional nature of western forms of aid, Zimbabwe has seen an increase in the aid it receives from China. In a report produced by AFRODAD (2019), based on statistics from the China World Investment Tracker, Zimbabwe received in excess of US$9 billion in aid, investment and grants between 2005 and 2019. The bulk of this has been targeted towards infrastructure projects such as the upgrading of the Kariba and Hwange Power Stations; the upgrading of Victoria Falls and Robert Mugabe International Airports; the construction of the new Parliament of Zimbabwe building in Mount Hampden and significant investments targeted at resuscitation of steel production in Zimbabwe. When it comes to Russia, the support provided to Zimbabwe has mostly been on the economic front in the areas of mining, agriculture, energy as well as the educational and scientific fields – though it has not been as significant as China.

Since 2000, Zimbabwe has adopted a deliberate “Look East Policy” to get aid from China and countries like Russia. Governments in Africa generally prefer aid from the Eastern countries because it is not tied to conditionalities of good governance, democracy and the upholding of the rule of law. It is still early to conclude how effectiveness this new form of aid from the east has been. Zimbabwe for example still faces challenges with the economy and the provision of social services to the majority of the population. There is a possibility however that in the long run, this aid can contribute to infrastructure development which in turn might be a positive booster for reviving the economy. It is therefore not possible for this paper to make any conclusions on the effectiveness of this new aid from the East. What has been clear since 2000, however, has been how both the government and population in Zimbabwe have managed to adjust and survive under conditions of declining foreign aid.

This next section of the paper unpacks what has been happening – how ordinary people and communities have survived and worked with each other and for each other to navigate the socio-economic and political challenges the country has faced over the last 22 years. A key issue which has not been sufficiently discussed in existing debates about progress and development in Zimbabwe is how communities in particular and the country in general survived without substantive aid from outside.

Associational Life, Giving and Solidarity Mechanisms in Zimbabwe

For a country such as Zimbabwe which has undergone many years of an underperforming economy, contested governance models leading to a political stalemate, decreased levels of service delivery and increased social and political crises, it is very easy to not see that in the midst of all this, citizens have tended to develop mechanisms of resilience and just go on with their lives as if the government did not exist. More often, there is a misdiagnosis of what holds the center together, if the analysis is not devoted to the actions and activities of citizens. Zimbabweans have endured more than two decades of crises that have led to one of the biggest migrations in sub–Saharan Africa. The statistics on the number of Zimbabweans who have emigrated are a bone of contention and vary with Afro Barometer indicating that there were approximately three to four million Zimbabweans living outside the country (Ndoma, 2017); while others estimate the figure to be as high as seven million. The top destinations for Zimbabwean migrants include – South Africa, the United Kingdom, Australia, and the United States. Yet amidst all this, the space has been held together by networks of solidarity, reciprocity, mutuality, and trust. In a study carried out in 2020 of citizens in Harare and the social, economic and political networks that they belonged to, 49% of respondents indicated that they belonged to a social support association, while 40% of respondents indicated that they belonged to an economic association/formation – such as a savings and lending group; a housing cooperative or buying club (Mususa, 2021). Citizens have continued to survive in their different formations and groupings. These formations have kept the hope for democracy and pluralism alive. They have made sure that Zimbabweans continue as a nation to yearn for a free, prosperous and developed society. The formations have continued to provide spaces for cooperation in solving problems faced by the nation.

Given the various moments that Zimbabwe has gone through, it is glaring that there are very few studies that help us appreciate the role that associations and networks play in society. In order to make sense of development, it is critical that there is an understanding and appreciation of the role that social networks play in sustaining the fibre of a society. The mechanisms of resilience that keep people together are best captured under the notion of associational life. Associational life has long been a studied phenomenon especially in the United States of America and in some developed nations like Italy. Associational life is normally defined as “a web of social relationships through which citizens pursue joint endeavours-namely, families, communities, workplaces, and or religious congregations”. Many observers have argued that these networks and their various institutional models are critical in not only forming human beings’ characters and capacities, but they also provide meaning and purpose to human beings. These networks are also platforms and tools that citizens use to respond and address societal challenges, most of which are developmental in nature. Yuval Levin (2017) aptly summarized this argument by stating that these mechanisms,

begin in loving family attachments. They spread outward to interpersonal relationships in neighborhoods, schools, workplaces, religious communities, fraternal bodies, civic associations, economic enterprises, activist groups, and the work of local governments. They reach further outward toward broader social, political, and professional affiliations, state institutions, and religious affinities. And they conclude in a national identity that among its foremost attributes is dedicated to the principle of the equality of the entire human race. (p. 4)

Zimbabwe’s political and economic landscape has given rise over the years to the emergence of several associations, mainly in response to societal needs and more recently due to the failure of the state to meet its service delivery functions. Michael Bratton (1989) in the review of Beyond the State: Civil Society and Associational Life in Africa, writes that;

Forms of associational life have evolved in rural Africa that address the direct needs of peasant producers for survival, accumulation, and reproduction under harsh and unpredictable conditions. (p. 413)

These associations were aptly called ‘the economy of affection’ by Goran Hyden (1980). Hyden argued that voluntary organizations with indigenous roots-for example, rural savings societies and nongovernmental welfare associations-are able to undertake fundamental developmental tasks like accumulation and distribution (119-28). For the urban poor, studies have been conducted across Africa, including in Zimbabwe that show that associational life is a crucial element in their coping strategies. Ilda Lourenco-Lindell for example, looking at Guinea-Bissau, argued that,

Informal networks of mutual assistance, notwithstanding their loose nature, are critical in the coping strategies of poor urbanites. Being embedded in webs of social relationships, people gain access to niches of the urban informal economy, find places to live, and are sustained through crises

(Tostensen et.al., 2001, p. 27).

Put differently, these networks are platforms to reduce the vulnerability of the poor. AbdouMaliq Simone’s study of Soumbedioune in Dakar and Johannesburg undertaken in the late 1990s emphasizes the fluidity of informal networks. However, it is this “fluidity that defies formalization and produces a situation of invisibility” that makes this a powerful platform and flexible tool for “responding to windows of opportunity, as and when they appear” (ibid, 28). Miranda Miles (2001) in her study of informal networks of women in Swaziland shows that in vulnerable positions on the lower rungs of the employment ladder, individuals, households and communities mobilize whatever resources they command to eke out a living. Apart from the tangible assets at their disposal, women create and draw on networks to enhance their resilience and chances of survival. These informal reciprocity networks derive largely from long-standing rural traditions of communal work parties, which are recreated in the city to form a basis for the acquisition of resources within an urban setting (ibid; 28).

According to Miles (2001), female urbanites rely on informal networks for their survival. They mobilize resources through rotating savings and credit systems whose members contribute a certain amount on a regular basis. Upon sharing of proceeds, the money can be used for any purpose at the discretion of the member. Some have used this system to buy land, property and/or to start a business. In addition, Miles shows that these networks are also used by the members as a therapeutic function in terms of well-being (Miles, 2001).

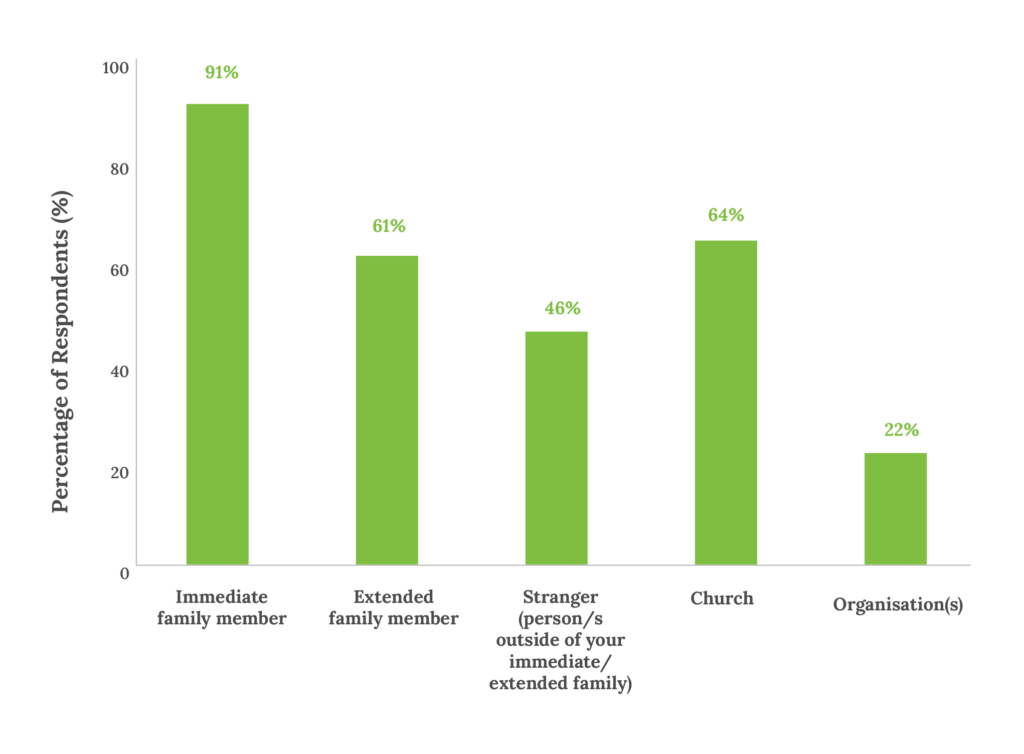

As a coping mechanism, most of these survived through extended families, and remittances both from within and from the diaspora. Diaspora remittances to Zimbabwe have risen significantly over the last 3 years. In 2020, the Reserve Bank of Zimbabwe recorded diaspora remittances of just over USD1 billion (CGTN Africa, 2021). In June 2022, remittances of USD1,372 billion had been recorded (Kazunga, 2022). It is also in times of shortages that citizens become innovative and look for alternative survival modes. The survey undertaken by SIVIO Institute in 2020, demonstrated that 42% of respondents depended on diaspora remittances and 26.51% have no options at all, while 44.56% depended on casual or piece jobs. A separate study by Jowah (2020) on giving by Zimbabweans showed that in 2019, 91% (1140) respondents had in the last six months given to immediate family members while 64% (794 respondents) had given to the church and 61% (759 respondents) had given to their extended families. In other words, giving, technically called philanthropy, played a major role in keeping families together.

The various associations found in several countries in Africa are not unique to those countries, they are also present in Zimbabwe. A nationwide survey carried out by SIVIO Institute of 2, 449 people in various parts of Zimbabwe, showed that people who are unemployed (26.20%) and those who are in the informal economy (40.84%) comprised the majority. Only 22.44% are in the formal sector with what can be called a formal employment position. About 49.69% of these were female. The majority of these were in the age groups 18-25 years old (24.46%), 26-35 years old (30%) and 36-45 years old (23.7%). In other words, those between the ages of 18 and 35 years of age constituted 54% while those between 36 and 55 years old made up of 37%. Put differently, 67% of those who were surveyed are either unemployed or operating in the informal economy. These are drawn mainly from the ages 18-55 years old who comprised 91% of those surveyed. This spells social unrest and the creation of vulnerable social structures, especially in a society that has high levels of literacy such as Zimbabwe. The survey showed that 97% of the respondents said they could read and write. More than 40% had attained tertiary education and 51% had obtained secondary education. And more than 66% lived in an urban setting.

Looking deeper into those who are in the formal sector, it is clear that the majority of them are in education (15.9%), civil service (13.74%), retail (12.12%) and mechanics and engineering (12.6%). Thus, the productive sectors of the economy are not absorbing much of the workforce. As a result, most citizens’ monthly incomes are not adequate to meet their basic needs. About 87.61% of the respondents from across 31 rural and urban areas had an income that did not meet their basic needs compared to 12.39% who said their incomes are adequate.

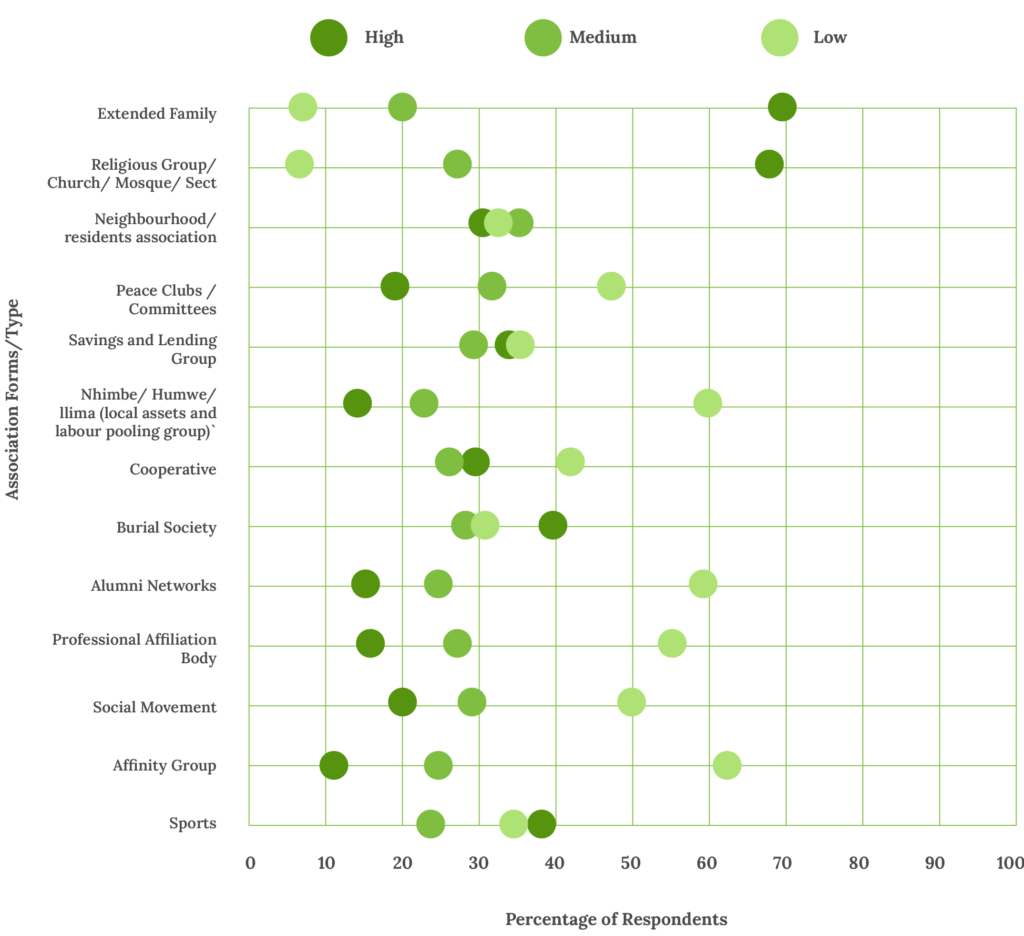

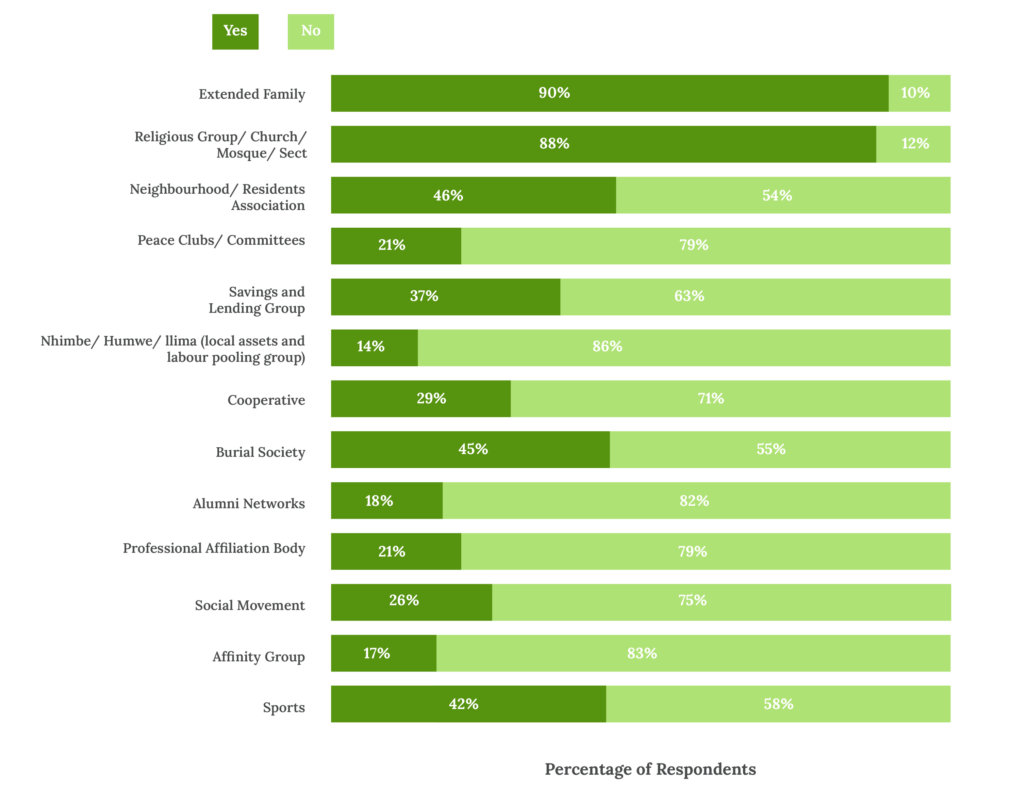

The findings by Jowah highlighted above are not surprising given that in the survey conducted by SIVIO Institute in December 2019, when citizens were asked to identify networks that mattered the most to them, the majority (73.12%) ranked extended family highly, followed by religious groups, churches or mosque (64.93%). Other networks that mattered included sports clubs (38.76%), burial societies (39.99%), savings and lending groups (34.79%), residents associations (31.15%) and cooperatives (29.58%). It is worth noting here that networks that are closer to the communities are ranked higher in terms of importance while those that are a bit removed from communities such as affinity groups, professional bodies and alumni networks are scored very low. As Figure 3 shows, most Zimbabweans were in 2022 not engaging that much with social movements, peace clubs and affinity groups as they did with those networks that have an opportunity to grant them access to economic opportunities, provide coping mechanisms and also spaces for healing such as churches. The existence of savings clubs, burial societies and cooperatives among Zimbabweans is historically grounded in many communities and has always served to cushion families and individuals in times of need.

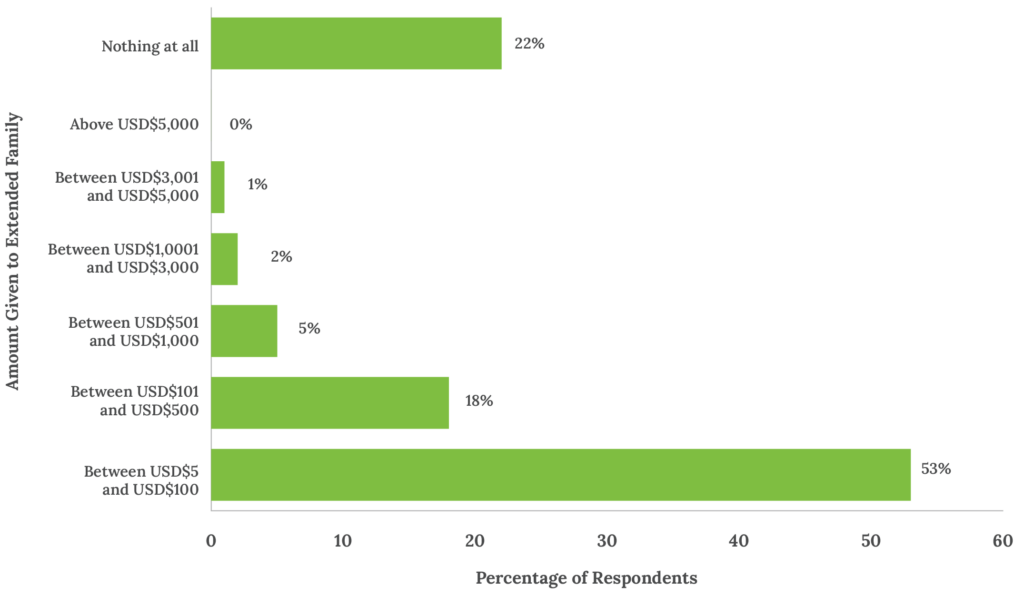

It is clear that for development to make sense, attention needs to be given to how people relate with each other in their extended families, in their religious congregations and most importantly for economic reasons, how they establish savings, lending clubs and cooperatives. The importance of extended families is also captured in the study by Jowah (2020) mentioned above. The study shows patterns of giving and quite interestingly the majority of people give to extended families consistently. About 53% gave an average of between USD$5 and USD$100 to their extended families in the last six months.

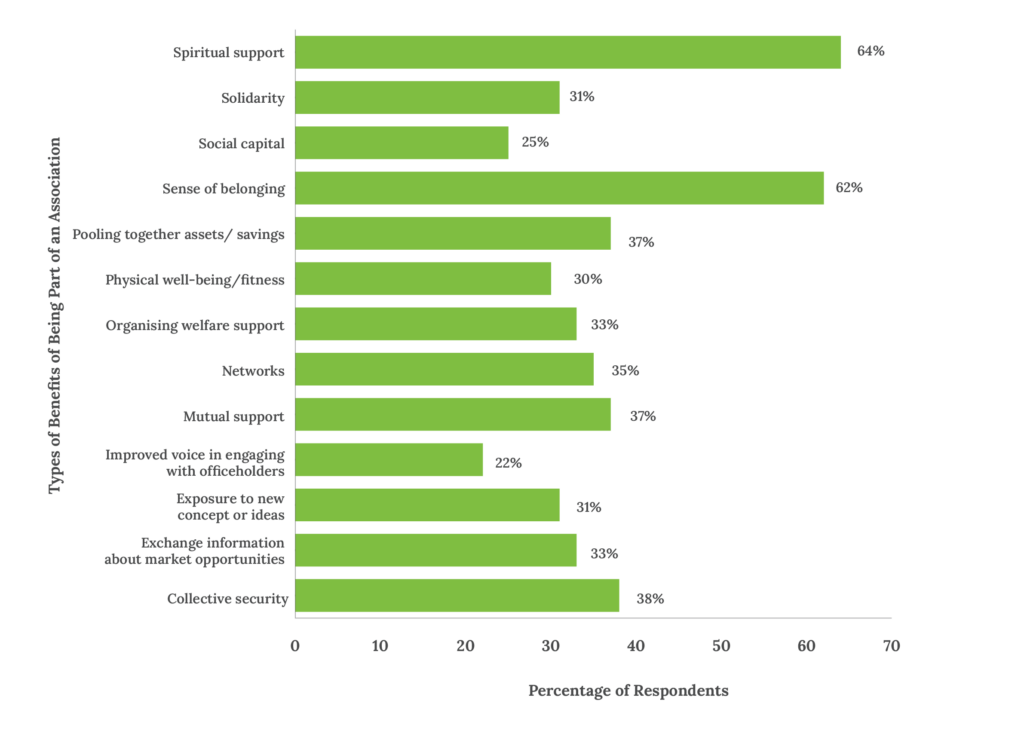

It is a well-known fact that in Zimbabwe, families depend on the community for burying their beloved. This is an old practice that has kept the social fibre intact. Burial societies, residents, associations and saving clubs are highly prioritized. There is a close relationship between the networks that are prioritized and the benefits thereof. Most of the respondents in our survey showed that citizens belong to churches and other networks for spiritual support (64%). Secondly, citizens participated in networks because they wanted a sense of belonging (62%). This is mainly true of extended families, churches and to some extent sports clubs. Thirdly, collective security (38%) and finally pooling together assets (37%), mutual support (37%) and networks (25%) also mattered for citizens. This would be of significance for those who participate in residents’ associations, savings clubs, burial societies and cooperatives. Finally, there is a high number of citizens who participate in networks and associations for solidarity and mutual support (68%) as depicted by Figure 5.

It is significant that 64% of respondents participate in religious networks mainly for spiritual support. This is not far from the demographics of Christians and other religions in sub-Saharan Africa. Gina A. Zurlo (2017) shows that Christians in 2016 comprised 58%, while Muslims constituted 29.4%, and Ethno-religionists (10.6%) and others (1.4%). In 2016, there were 52 million Christians in Southern Africa alone with a population of 59.83 million. Given the many challenges that Zimbabweans face, there is the possibility of fragmentation, alienation and atomization. To avert this, it is clear that citizens seek those platforms that make them feel they belong. It is not surprising that more than 60% would seek a sense of belonging in networks. This is a tested mechanism for resilience building and a coping strategy, especially among the urban poor. In Bowling Alone, Putnam (2001), wrote:

Faith communities in which people worship together are arguably the single most important repository of social capital…. As a rough rule of thumb, our evidence shows nearly half of all associational memberships in America are church-related, half of all personal philanthropy is religious in character, and half of all volunteering occurs in a religious context (p. 66).

The Social Capital Project (2017) alluded to earlier argues that “religious institutions that convene people under the banner of shared beliefs have powerful community-promoting advantages over secular institutions”. It further argues that these religious institutions “provide a vehicle for like-minded people to associate, through regular attendance at religious services and other events and charitable activities they sponsor”. It adds that religious institutions are “highly effective at enforcing commitment to shared principles and norms of behaviour, passed down over generations” (Op. cit., 26). Robert Putnam further argued that religious institutions promote investments in social ties outside the participants’ denominations. He concluded that people who are committed to religion,

Are much more likely than other people to visit friends, to entertain at home, to attend club meetings, and to belong to sports groups; professional and academic societies; school service groups; youth groups; service clubs; hobby or garden clubs; literary, art, discussion, and study groups; school fraternities and sororities; farm organizations; political clubs; nationality groups; and other miscellaneous groups.

(Op. cit., 67)

Neighbourhood associations and residents’ associations are also important networks for Zimbabweans. As seen in the survey, about 46% of respondents belonged to a resident or neighbourhood association. This figure is high and suggests that citizens have come together in response to some of the service delivery challenges facing government. The biggest attractions for belonging still remain the extended family (90.13%); followed by religious groups (87.67%), sports clubs (57.92%) and then burial societies (44.76%) and savings clubs (37.36%). This is in line with the order of importance that respondents accorded to each type or form of association as demonstrated in Figure 2 above whereby order of importance, extended family ranked first (73.12%), followed by religious institutions (69.93%) and burial societies, sports, savings clubs and residents associations.

Theories of social capital argue that neighbourhoods with a healthy associational life provide a number of advantages to their residents. Research has also shown that communities with higher levels of trust and a greater willingness to address community problems have lower levels of crime (Sampson, 2012). Other researchers have also argued that communities, in which individuals help and look out for each other, are more willing to pool common resources, when necessary for example, after a natural disaster (Murphy, 2007). In the case of Zimbabwe, this has been demonstrated in recent examples such as the cholera outbreak in 2018 and the devastating cyclones Idai and Kenneth where groups such as Childline Zimbabwe, Econet Zimbabwe, Kidzcan Cancer, Children’s Homes, and Higherlife Foundation, among others responded to address various needs. Additionally, it has been noted that neighbourhoods with healthy associational life seem to offer children greater prospects and opportunities for upward mobility within society (Chetty & Hendren, 2015).

The rise of residents’ associations (RAs) in Zimbabwe is linked always to the decline in service delivery by urban councils. Musekiwa and Chatiza (2015) argue that although residents’ associations predate independence, their visibility and numbers today has dramatically grown since 1980, with a spike in the post-2000 period. This is due to the post-2000 socioeconomic crisis that gripped Zimbabwe which resulted in weakened capacity of urban authorities to deliver basic essential services, such as housing, water, electricity, basic education, refuse removal and primary health. Residents responded to this failure by creating residents’ associations and creating visibility of such associations. As the writers argue, residents’ associations are established by citizens as pressure groups to ensure that councils improve service delivery and that in a democratic society, councils are accountable to ratepayers. This is crucial for development.

The history of residents’ associations in Zimbabwe also reveals the shifts that have occurred over the years in their functions and mandate. Musekiwa and Chatiza (2015), for example, illustrate that the Gweru Residents’ Association was in pre-1980 the voice of ‘blacks’ in enhancing access to urban services while Mutare Residents and Ratepayers Association focused on the service delivery challenges faced by residents in high-density areas of Mutare-then Umtali (ibid, 124). In the post-2000 period, residents’ associations that were formed continued with the focus on citizens’ participation and access to services. This was the case with the Harare Combined Residents Association while the Mutare Combined Residents and Ratepayers Association was established to address issues of access to clean water, streetlights, and refuse collections mainly in low-income suburbs. Residents’ associations, therefore, emerge in response to the loss of faith in local government to deliver services. RAs are also established to compliment or replace local government system. In this case, RAs also ‘play the role of nudging and guiding local authorities. Secondly, RAs emerge to address short to medium-term issues. These are mostly operational matters that are not long-term in nature. These associations have not positioned themselves in the urban areas only. The Masvingo United Residents Association for example is reported to have helped create RAs at rural service centers such as Nyika, and Mupandawana in Bikita and Gutu (ibid, 124).

In addition to advocacy and policy influence, RAs are also involved in service delivery. In Bulawayo, Musekiwa and Chatiza report that the Bulawayo Residents Association assisted with pauper burials-conducting 80 such in 2008. The Association also assisted by mobilizing funds for Mpilo hospital to repair the mortuary and laundry facilities. BURA is reported to have also run an HIV/AIDS programme in Bulawayo. The Harare Combined Residents Association is also said to be running a funeral fund. And in Mutare, the CMRRA mobilized communities for a reforestation and gully reclamation initiative in Dangamvura suburb. RAs also represent citizens on issues of public good. They also hold authorities accountable. All these are critical functions in a democracy.

Urban housing cooperatives are also another network that has provided an avenue for citizens to address problems associated with housing. Just like the residents’ associations, the cooperative movement in Zimbabwe predates independence. The Cooperative Societies Act 193 was passed for example, in 1956. The number of cooperatives has grown exponentially. For example, by 1990, there were 1100 cooperatives and by early 2000s, the numbers had quadrupled (Butcher, 1990). Today there are more than 200 urban housing cooperatives. Harare alone has more than 80 of these (Kamete, 2007). The same is true of school associations that have been proven to result in higher school quality and better child outcomes.

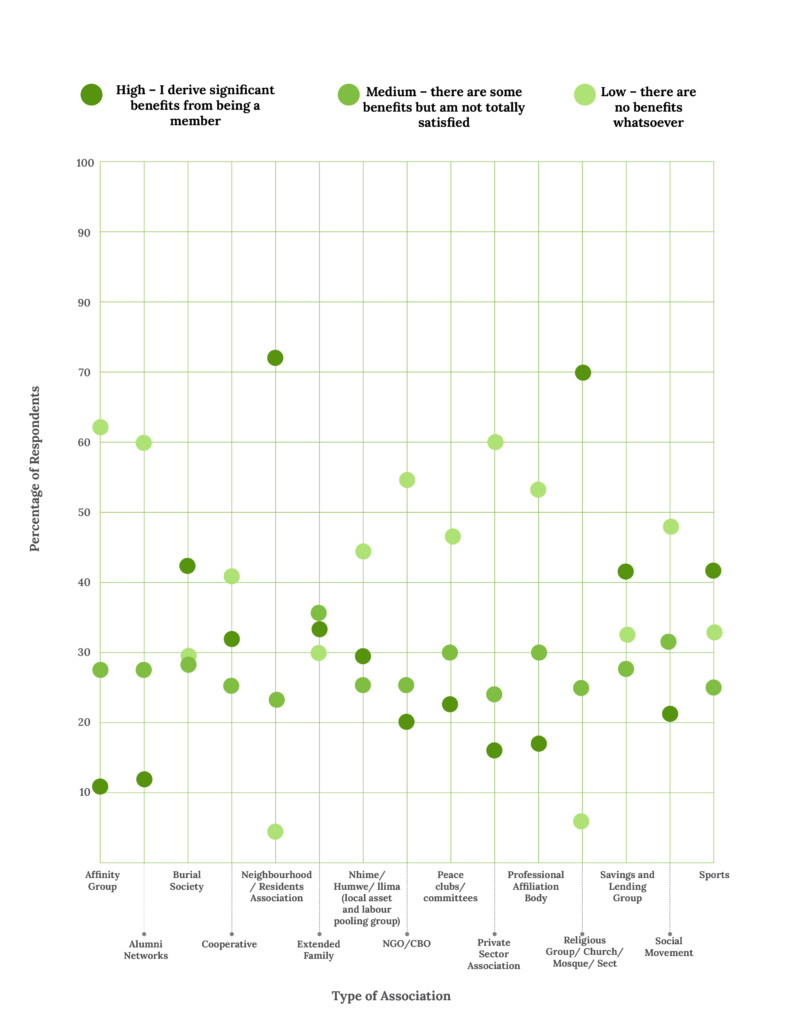

From the December 2019 survey, it seems as if respondents are overall satisfied with the performance of the networks that they belong to. More than 70% of the respondents derived significant benefits from belonging to an extended family group while 22% benefited moderately from extended family membership. This is over 90% of people who derive benefits that range from significant to moderate benefits. Secondly, close to 70% of respondents benefited significantly from their membership in a religious group while 25% benefited moderately. The trend is the same as with the importance of the association that citizens belonged to or participated in. Figure 7 illustrates this. Quite interestingly, there are very few people who see benefits from belonging to a Non-Governmental Organization or Community-Based Organization. Only 28.73% say they derived significant benefits from these compared to 59.89% who say there are no benefits. This signals a shift to locally based structures as opposed to national and or regional groupings like NGOs.

Benefits of association can also be a function of the extent to which a member is active in the association. When asked if they held positions in the association in which they are members, less than 40% said they were in each type of association.

Giving and Solidarity During COVID-19

When the pandemic broke and during the period under lockdown, there were a number of citizen-led giving initiatives established across Zimbabwe. Desktop research by Jowah, Garwe and Satuku (2021) from March to June 2020, uncovered 60 local citizens-led/driven initiatives established to help counter the impact of COVID-19. The pandemic helped showcase and highlight numerous acts of giving from grassroots to large corporate and government levels. It was a phenomenon across the continent and worldwide. The giving that took place in Zimbabwe was even more remarkable in that this giving has been happening amid a long-term economic crisis (Jowah, Garwe and Satuku, 2021). One of the most significant examples of this giving was resources mobilised under the Solidarity Trust of Zimbabwe which raised about USD450,000 and ZWL15 million from Zimbabwean corporates and individuals (based locally and in the diaspora). Such giving follows on from other crisis moments that the country had faced where there was limited government capacity and donor aid – e.g., during the Cholera epidemic in 2015 and with Cyclone Idai in 2019, citizens came alongside the government to mobilise resources to help deal with these crises and support those most heavily impacted by these events.

It is largely due to actions of citizens’ solidarity that the country has not completely collapsed despite economic challenges and the decrease in the provision of social services at the local and central government level and the limited foreign aid inflows. It highlights that in order to advance the country’s development – it cannot be just a state driven or a combination of state and foreign aid-driven development. Ordinary citizens have assets that they can mobilise and draw upon to advance development. There is, therefore, a need for a more inclusive approach towards development which is driven by citizens and government and foreign aid comes in to complement citizen resources.

Conclusion

This paper has sought to highlight and provide some insights into the lack of a total collapse of the country post-2000 despite the sustained economic and political crises the country has undergone for the last 22 years. It is important to begin to recognise and highlight the importance of how and what citizens do for and with each other have contributed to this lack of collapse. The forms of citizen solidarity should therefore be promoted and seen as important towards contributing to a more inclusive form of development for Zimbabwe. Citizens have often been left of the traditional forms of development strategies adopted – as has been the case around the use of aid – where the development challenges and solutions for citizens are often defined by others. The forms of citizen solidarity that have been highlighted in this paper have started to show how citizens can contribute towards and be part of the implementation of strategies to address the socio-economic and political challenges they face.

References

African Forum and Network on Debt and Development (AFRODAD). (2019). China-Zimbabwe relations: Implications on Zimbabwe’s development. AFRODAD, Harare – https://afrodad.org/wp-content/uploads/2021/04/Zimbabwe-China-relationship.pdf.

Ajayi, K. (2000). International administration and economic relations in a changing world. Ilorin: Majab Publishers.

Bird, K. & Busse, S. (2007). Re-thinking aid policy in response to Zimbabwe’s protracted crisis: A Discussion Paper. ODI.

Bratton, M. (1989). ‘Review’: Beyond the state: Civil society and associational life in Africa. World Politics, 41(3), 407-430.

Butcher, C. (1990). ‘The potential and possible role of housing cooperatives in meeting the shelter needs of low income urban households. ZIRUP: Harare.

CGTN Africa. (2021). Zimbabwe receives record $1 billion in remittances from diasporeans. Retrieved from https://rb.gy/phvisa.

Chetty, R. & Hendren, N. (2015). The effects of neighbourhoods on intergenerational mobility II: Country level estimates, (Working paper series 23002, National Bureau of Economic Research) accessible on www.nber.org/papers/w23002.

Chikowore, G. (2010). Contradictions in development aid: The case of Zimbabwe. Special Report on South-South Cooperation 2010. https://rb.gy/upcsl4.

Dashwood, H. S. (2000). Zimbabwe: The political economy of transformation. University of Toronto Press. Toronto and London.

Easterly, W. (2009). “Can the West save Africa?” Journal of Economic Literature, 47(2): 373-447.

Galeano, E. (1992). We say no: Chronicles 1963-1991 (1st American). New York: W.W. Norton.

Government of Ghana. (2019). Ghana beyond aid charter and strategy document. Retrieved from http://osm.gov.gh/assets/downloads/ghana_beyond_aid_charter.pdf.

Gurukume, S. (2012). Interrogating foreign aid and the sustainable development conundrum in African countries: A Zimbabwean experience of debt trap and service delivery. International Journal of Politics and Good Governance Volume 3, No. 3.4 Quarter IV 2012.

Hyden, G. (1980). Beyond Ujamaa in Tanzania: Underdevelopment and an uncaptured peasantry. Berkeley: University of California Press.

IMF. (2022): Press Release No.22/310 IMF Staff Concludes Staff Visit to Zimbabwe. IMF Staff Concludes Staff Visit to Zimbabwe.

Jowah, E. (2020). Perceptions of giving: Findings from a survey on giving by Zimbabweans. Harare: SIVIO Institute.

Jowah, E., Garwe, S. & Satuku, S. (2021). The best of us in the worst of times, A review of giving during the Corona Virus Pandemic COVID-19 and philanthropic responses. SIVIO Institute – https://rb.gy/xsp2m9.

Kamete, A.Y. (2001). Civil society, housing and urban governance: The case of urban housing cooperatives in Zimbabwe, in Tvedten Tostensen. Associational Life in African Cities: Popular Responses to the Urban Crisis. Oslo: Nordic Africa Institute, pp 162-179.

Kazunga, O. (2022). Diaspora remittances hit US$800 million: The Herald. Retrieved from https://www.herald.co.zw/diaspora-remittances-hit-us800-million/.

Lancaster, C. (2007). Foreign aid: diplomacy, development, domestic policies. (1st Ed.). Chicago: University of Chicago.

Levin, Y. (2017). The Fractured republic: Renewing America’s social contract in the age of individualism. New York: Basic Books.

Levy, S. (2016). Poverty in Latin America: Where do we come from, where are we going? Brookings. Retrieved from https://rb.gy/x5nfhc.

Melesse, T. M. (2021). International aid to Africa needs an overhaul. Tips on what needs to change. The Conversation: Africa Edition – https://rb.gy/40b5as.

Miles, M. (2001). Women’s groups and urban poverty: The Swaziland experience. In Tostensen, T. et.al, (2001). Associational life in African cities: Popular responses to the urban crisis. Oslo: Nordic Africa Institute.

Moyo, D. (2009). Dead aid: Why aid is not working and how there is another way for Africa. London: The Penguin Group.

Moyo, L. & Mafuso, L. (2017). ‘The effectiveness of foreign aid on economic development in developing countries: A case of Zimbabwe (1980-2000)’. Journal of Social Sciences. 52, 173-187. 10.1080/09718923.2017.1305554.

Moyo, S. (1995) “The impact of foreign aid on Zimbabwe’s agricultural policy.” Africa Development / Afrique et Développement, 20(3): 23–50. http://www.jstor.org/stable/24486880.

Murphy, B.L. (2007). ‘Locating social capital in resilient community-level emergency management’. Natural Hazards, 41(2), 297-315.

Musekiwa, N. & Chatiza, K. (2015). Rise in resident associational life in response to service delivery decline by urban councils in Zimbabwe’. Commonwealth Journal of Local Governance, 16 (17).

Mususa, D. (2021). ‘Exploring citizenship: The lived realities around associational life in Zimbabwe’. African Journal of Inclusive Societies, Vol 1 (October 2021): 196-258. https://rb.gy/cs0bsw.

Murisa, T. (2022). Rethinking citizens and democracy. Harare: SIVIO Institute.

Ndoma, S. (2017). Almost half of Zimbabweans have considered emigrating; job search is the main pull factor. Afro Barometer. Retrieved from: https://rb.gy/jkts2e.

Putnam, R. (2001). Bowling alone: The collapse and revival of American community. New York: Simon & Schuster.

Rostow, W.W. (1960). The stages of economic growth: A non-communist manifesto. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press.

Sampson, R. J. (2012). Great American city: Chicago and the enduring neighbourhood effect. Chicago: University of Chicago Press.

Simone, A. (2001). Between ghetto and globe: Remaking urban life in Africa in Tostensen, T. et.al, (2001). Associational life in African cities: Popular responses to the urban crisis. Oslo: Nordic Africa Institute.

Sogge, D. (2002). What’s the matter with foreign aid? Dhaka: Red Crescent Building and The University Press Ltd.

Sun, Y. (2014). China’s aid to Africa: Monster or Messiah? The Brookings Institution (Op. Ed.). [Online]. Available: https://www.brookings.edu/opinions/chinas-aid-to-africa-monster-or-messiah/.

Tarp, F. (2012). Aid effectiveness. Available: https://www.un.org/en/ecosoc/newfunct/pdf/aid_effectiveness-finn_tarp.pdf.

The Social Capital Project. (2017, May). Prepared by The Vice Chairman’s Staff of the Joint Economic Committee at the Request of Senator Mike Lee.

Tostensen, T. et.al, (2001). Associational life in African cities: Popular responses to the urban crisis. Oslo: Nordic Africa Institute.

WIDER, U.N.U. (2020). A snapshot of poverty and inequality in Asia: Experience over the last fifty years. WIDER Research Brief 2020/2. Helsinki: UNU-WIDER – https://rb.gy/dqmi3h.

World Bank. Net official development assistance received (current US$) – Zimbabwe. Retrieved from https://data.worldbank.org/indicator/DT.ODA.ODAT.CD?locations=ZW.

World Bank. (2021). Zimbabwe Reconstruction Fund (ZIMREF) Annual Report 2021. Washington: World Bank Publications. https://rb.gy/mteknu.

World Bank. (2022). The World Bank in Zimbabwe overview – Strategy. https://www.worldbank.org/en/country/zimbabwe/overview#2.

Zurlo, A. G. (2017). A demographic profile of Christianity in Sub Saharan Africa (edited by Kenneth R. Ross, J. Kwabena Asmaoh-Gyadu and Todd M. Johnson). Edinburgh: Edinburgh University Press; 3-18.