Peer-review started: June 17, 2016

First decision: July 4, 2016

Revised: September 23, 2016

Accepted: October 25, 2016

Article in press: October 27, 2016

Published online: January 6, 2017

To compare laparoscopic and open living donor nephrectomy, based on the results from a single center during a decade.

This is a retrospective review of all living donor nephrectomies performed at the Massachusetts General Hospital, Harvard Medical School, Boston, between 1/1998 - 12/2009. Overall there were 490 living donors, with 279 undergoing laparoscopic living donor nephrectomy (LLDN) and 211 undergoing open donor nephrectomy (OLDN). Demographic data, operating room time, the effect of the learning curve, the number of conversions from laparoscopic to open surgery, donor preoperative glomerular filtration rate and creatinine (Cr), donor and recipient postoperative Cr, delayed graft function and donor complications were analyzed. Statistical analysis was performed.

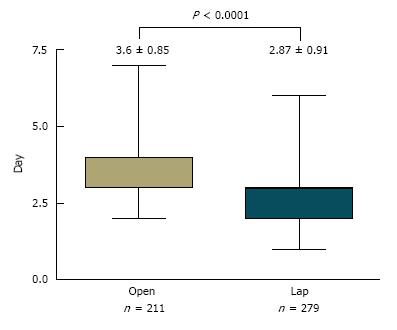

Overall there was no statistically significant difference between the LLDN and the OLDN groups regarding operating time, donor preoperative renal function, donor and recipient postoperative kidney function, delayed graft function or the incidence of major complications. When the last 100 laparoscopic cases were analyzed, there was a statistically significant difference regarding operating time in favor of the LLDN, pointing out the importance of the learning curve. Furthermore, another significant difference between the two groups was the decreased length of stay for the LLDN (2.87 d for LLDN vs 3.6 d for OLDN).

Recognizing the importance of the learning curve, this paper provides evidence that LLDN has a safety profile comparable to OLDN and decreased length of stay for the donor.

Core tip: The experience of the Massachusetts General Hospital was reviewed to compare laparoscopic vs open donor nephrectomy in a 10-year period. A review of the results of operating room time and conversions to open made the importance of the learning curve apparent. Although there was no difference in the recipient kidney function, the length of hospital stay was significantly shorter for the laparoscopic procedure. Overall, the laparoscopic donor nephrectomy appears to be the preferred surgical approach, considering the importance of the learning curve.

- Citation: Tsoulfas G, Agorastou P, Ko DSC, Hertl M, Elias N, Cosimi A, Kawai T. Laparoscopic vs open donor nephrectomy: Lessons learnt from single academic center experience. World J Nephrol 2017; 6(1): 45-52

- URL: https://www.wjgnet.com/2220-6124/full/v6/i1/45.htm

- DOI: https://dx.doi.org/10.5527/wjn.v6.i1.45

Laparoscopic living donor nephrectomy (LLDN) is not a novel procedure, since the first one was performed in 1995 by Ratner et al[1] and it was subsequently made easier to learn with the description of the hand-assisted approach by Wolf et al[2] and Slakey et al[3]. This, together with the appeal of a less invasive procedure, led to the majority of living donor nephrectomies (LDN) being performed laparoscopically by 2005 according to the United Network of Organ Sharing, and with several large series arguing in favor of the safety and efficacy of the procedure, as well as its positive effect on increasing the donor pool[4-7]. Despite this positive momentum, it is interesting that there are still many questions that remain unanswered, or at least not fully answered.

A review of current trends and practice patterns by Wright et al[8] in 2008, surveyed 58 fellowship training programs for renal transplantation in the United States accredited by the American Society of Transplant Surgeons. With 32 centers responding (55%), and representing approximately 40% of laparoscopic living donor nephrectomies in the United States, it became obvious that there is variability among different centers. Specifically, there were differences in donor selection [about one third of centers excluding donors with a body mass index (BMI) > 40 kg/m2 or only 40% of centers considering a kidney with a simple cyst suitable for donation], choice of laparoscopic technique (40% of centers using only pure laparoscopy, 20% only hand-assisted laparoscopy and the rest a combination), and technical surgical aspects (whether to control the renal artery of the donor with a vascular stapler or a plastic or metal clip, or the type of incision)[8].

More importantly, and even though a concern about underreporting remains, there have been reviews of the literature which have reported at least eight perioperative deaths with LLDN[9]. The seriousness of this can only be fully understood if we consider that living donation represents a unique type of surgical procedure, where a healthy person undergoes an operation with significant risk, without any biological benefit for themselves; that is, the donor will not feel any better or be any healthier after the surgery. For this reason, we have to understand that the safety of the living donor is paramount. That is the main reason why, despite the existing studies, it is very important to welcome further studies evaluating the results of living donation, as well as to encourage centers to assess their own results and share the lessons learnt. This becomes even more critical today, given the fact that because of the progress of LLDN, there is increasing pressure to use more high-risk donors, such as those with a higher BMI or donors with complex renal anatomy.

From January 1998 to December 2009, there were 490 LDN performed at the Massachusetts General Hospital, including 279 LLDNs and 211 open living donor nephrectomies (OLDNs) (Table 1). The decision between the open or the laparoscopic procedure, after the latter was introduced at our center in 1998, was a combination of patient’s and surgeon’s preference. Although originally the left kidney was the preferred one for the LLDNs, because of the longer vein, with increasing experience, kidney side, number of renal arteries or previous surgeries were not obstacles to LLDN. The main criterion regarding the procurement was choosing the “less healthy” kidney, so that the “better” one would remain with the living donor.

| Laparoscopic nephrectomy | 279 |

| Left | 260 |

| Right | 19 |

| Open nephrectomy | 211 |

| Left | 156 |

| Right | 55 |

All donors and recipients underwent extensive preoperative evaluation and testing by a multidisciplinary team before the decision was made to proceed with the donation. Patients underwent three-dimensional computed tomography and computed tomographic angiography, in order to evaluate renal size and anatomy, as well as the presence of any abnormalities. Donor and recipient medical records were reviewed, after approval from the Institutional Review Board. Information that was collected and analyzed included epidemiological data, and the LLDN and OLDN groups were compared regarding pre-, intra- and post-operative parameters, including pre- and post-operative donor and recipient renal function, operative time, the effect of the learning curve, delayed graft function, length of stay and complications. Delayed graft function was defined as the need for hemodialysis within a week after the transplantation. Additionally, the reasons for conversion from laparoscopic to open LDN were recorded. There were no statistically significant differences between the LLDN and the OLDN groups regarding age or gender.

Data are expressed as mean ± standard deviation. Statistical analysis used Student t test to asses group differences for continuous variable and statistical significance was defined as P < 0.05.

There were five different attending surgeons performing the donor nephrectomy, with the surgical team also including a transplant fellow. In the first 20 LLDN, there were two attending surgeons present and participating. The surgical technique for the OLDN was a standard retroperitoneal flank approach, without a rib resection. For the LLDN, the initial preferred technique was that of a hand-assisted transperitoneal laparoscopic procedure, given the increased security that it provides to the surgeon. Patients were in a flexed, lateral decubitus position and initial access consisted of the placement of a handport either around the area of the umbilicus or through a low transverse incision, which could later be used to retrieve the kidney. Frequently, a 7-9 cm Pfannenstiel incision was chosen, given the improved cosmetic result. The intraabdominal pressure was set to 10-12 mmHg, to avoid any effect on renal perfusion. Urine output was maintained at a brisk rate using aggressive intravenous hydration, supplemented with diuretics, and 5000 U of unfractionated heparin (when there was no contraindication) was given just prior to the renal artery occlusion. Originally, the artery was secured using locking polymer clips, but because of instances where the clips were not secure on the artery leading to bleeding, the decision was made that both the renal artery and vein would subsequently be secured with linear staplers. In the case of the right kidney being retrieved, the right renal vein was exposed at its insertion into the inferior vena cava and caval countertraction was applied just prior to firing the endovascular stapler, so that adequate length could be obtained. The postoperative protocol included analgesia with intravenous ketorolac on-demand (limited number of doses for only one day), removal of the Foley catheter on postoperative day 1 and advancing to a regular diet on day 2.

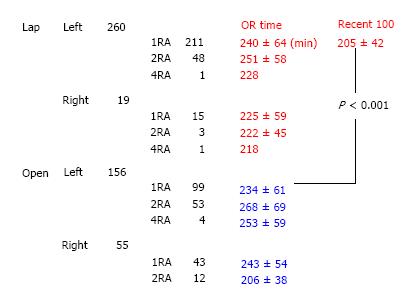

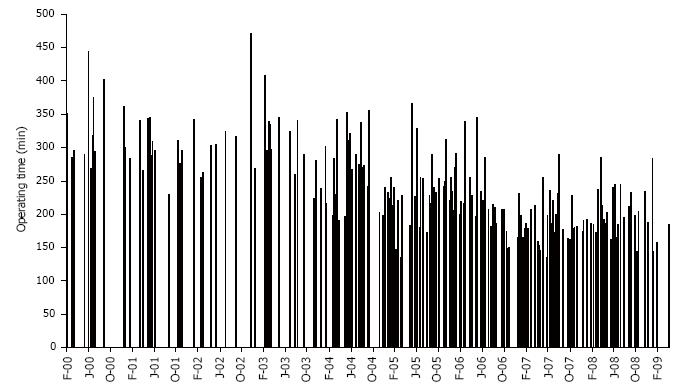

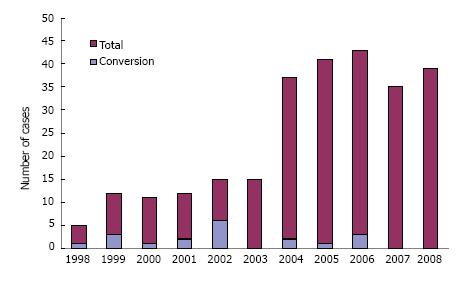

The LLDN and OLDN groups are presented in Table 1, including the information whether a left or a right kidney was retrieved. The preopeartive glomerular filtration rate was similar (LLDN = 128.4 ± 32 mL/min vs OLDN = 123.6 ± 26 mL/min) between the donors for the two groups (Table 2). The reasons for which the right kidney was chosen included number of arteries or veins, presence of cysts, size, presence of stones and a tortuous ureter, with the guiding principle being to always have the better kidney remain with the donor. Specifically, in the LLDN out of the 19 right nephrectomies, the right kidney was chosen in 15 donors because of a single artery, in 2 patients because of the presence of numerous cysts mainly on the right side and 1 patient because of a significant size difference with the left kidney being much larger than the right and in 1 patient because of the presence of stones in the right kidney that were removed ex vivo. In the case of the open LDN, there were 55 right kidneys used. Out of these, in 43 patients the right kidney was chosen because of a single artery, in 6 patients because of size differences between the two kidneys, in 4 patients because of the presence of cysts on the right kidney and in 2 patients because of a tortuous ureter. The small sample size did not allow for statistical differences between the two groups. The operating room time is shown in Figure 1 with the additional information of whether it was a left or right kidney, as well as the number of renal arteries. Analysis of the operating room time reveals no statistically significant difference between the LLDN and OLDN (LLDN = 227 ± 58 min vs OLDN = 244 ± 62 min). Interestingly enough, when the most recent 100 LLDN cases with single artery kidneys are compared to the last 100 OLDN cases with single artery, there is actually a statistically significant difference in favor of the laparoscopic procedure (100 recent LLDN = 205 ± 42 min vs OLDN = 234 ± 612 min, P < 0.001). The value of the learning curve is further showcased in Figure 2, where we can clearly see that there is a trend towards decreased operating room time as the years progressed and the experience accumulated. Another example of this is the number of conversions, which were a total of 18/279 (6.45%). The reasons for the conversions are shown in Table 3. There were no reoperations or readmissions required in these donors. The important point regarding the learning curve is that, as we can see in Figure 3, there was a decrease of conversions over the years, with no conversions occuring during the last two years.

| Laparoscopic LDN | Open LDN | |

| Donor preoperative GFR (mL/min ± SD ) | 128.4 ± 32 | 123.6 ± 26 |

| Donor preop Cr (mean ± SD) | 0.96 ± 0.4 | 0.88 ± 0.4 |

| Operative time (min ± SD ) | 227 ± 58 | 244 ± 62 |

| Donor postop Cr 1 mo (mean ± SD) | 1.43 ± 0.9 | 1.39 ± 0.8 |

| Delayed graft function (%) | 7.2% (20/279) | 6.6% (14/211) |

| Recipient postop Cr 1 mo (mean ± SD) | 1.43 ± 1.4 | 1.39 ± 1.1 |

| Major complications (%) | 7.5% (21/279) | 8.5% (18/211) |

| Reasons for conversion | Number of patients (n = 18) |

| Bleeding | 8 |

| Adhesions | 5 |

| Anatomy | 5 |

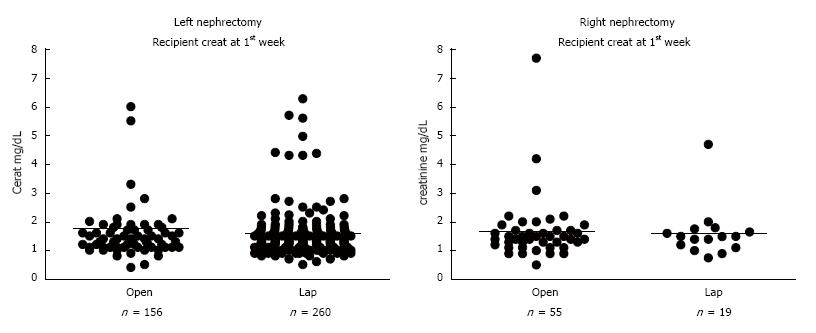

Regarding the efficacy of living donation, a key measure is recipient renal function. There were no statistically significant differences between the LLDN and the OLDN groups in recipient renal function at 1 wk (LLDN = 1.6 ± 1.2 mg/dL vs OLDN = 1.65 ± 1.3 mg/dL), or at 1 mo (LLDN = 1.43 ± 1.4 mg/dL vs OLDN = 1.39 ± 1.1 mg/dL), irrespective of whether the left or right donor kidney was transplanted (Figure 4, Table 2). Additionally, there was no statistically significant difference in the incidence of delayed graft function between the two groups (LLDN = 7.2% or 20/279 vs OLDN = 6.6% or 14/211). As far as the donor renal function is concerned, both the preoperative creatinine values (LLDN = 0.96 ± 0.4 mg/dL vs OLDN = 0.88 ± 0.4 mg/dL) and the postoperative ones at 1 mo (LLDN = 1.43 ± 0.9 mg/dL vs OLDN = 1.39 ± 0.8 mg/dL) were similar between the two groups (Table 2).

The one area where there was a statistically significant difference between the two groups was the length of stay (LLDN = 2.8 ± 0.91 vs OLDN = 3.6 ± 0.85) with donors in the laparoscopic group leaving the hospital earlier than their counterparts who had undergone an open procedure (Figure 5). Part of the reason was a postoperative fast-track protocol for the laparoscopic donors that included analgesia with intravenous ketorolac on-demand, removal of the Foley catheter on postoperative day 1 and advancing to a regular diet on postoperative day 2.

Finally, regarding the postoperative complications, although there was no statistically significant difference in the number of major complications between the two groups (LLDN = 7.5% or 21/279 patients vs OLDN = 8.5% or 18/211 patients), there was a difference in the types of complications with ileus, respiratory problems and incisional hernias being more frequent in the open living donor group. Regarding the timing of the complications, they were all in the immediate postoperative period (within 30 d), with the only exception being two episodes of ileus which occurred in the OLDN group. Specifically, these patients presented with ileus more than 6 mo after the surgery and were treated conservatively with bowel rest with success in both cases.

This report is a comparison of LLDN and OLDN. In order to do that, we present the experience of a single academic center over a 10-year period, starting with the advent of LLDN and how it evolved over time to the point that it came to replace OLDN as the main type of living renal donor procurement surgery. A review of our results reveals that although there was no statistical difference in the operating time between the two groups as a whole, when looking at the last 100 cases of LLDN with a left kidney and comparing them to the same number of OLDN with a left kidney, there was a significant improvement in the operating time in favor of the laparoscopic procedure. This serves to underline the importance of the learning curve, which is also shown in our results by the decreasing operating time over the years, as well as the decreased number of conversions in the laparoscopic group.

Additionally, when looking at donor and recipient renal function, as well as the incidence of delayed graft function, there is no difference between the two groups, leading to the conclusion that LLDN is at least as efficacious as OLDN when it comes down to renal function. The one area where there was a difference, was that of the length of stay, where donors spent almost a day less in the hospital following the laparoscopic procedure. Finally, in terms of their safety profile, there was no diffence in the incidence of major complications, which shows that the LLDN is at least as safe as the OLDN. Interestingly enough, there was a difference in the types of complications, with pulmonary complications, ileus and incisional hernias being more frequent in the OLDN group, something which is not unexpected considering the larger incision.

These results compare well to other studies in the literature, as a meta-analysis by Nanidis et al[10] showed that LLDN is a safe alternative to the open technique, and that although open nephrectomy was associated with shorter operating times (when only randomized controlled studies were analyzed), there was no difference in recipient postoperative renal function or the incidence of delayed graft function. The authors similarly found that donors undergoing laparoscopic nephrectomy were able to benefit from a shorter hospital stay. In contrast to our study, the authors report that when only randomized controlled trials were analyzed, it appeared that the rate of total postoperative complications favored the open procedure[10]. However, they do point out that this result was not reproducible in the sensitivity analysis, probably because the numbers of the randomized controlled trials were so low that a definitive conclusion could not be safely drawn. There are other large series of LLDN, where the laparoscopic technique is at least as safe as the open one, with overall complication rates around 6%-6.5%, similar to ours[11,12]. Obviously, one of the big questions is whether there is an issue of publication bias with underreporting of complications, as a survey of American transplant centers by Matas et al[13] showed a 0.03% mortality rate, as well as higher reoperation and readmission rates after laparoscopy. Although this must be taken very seriously into account, it could also be explained by factors such as these cases being early on in the learning curve of a center, as well as by the fact that transplant centers are more sensitive (and rightly so) with any potential complication having to do with a living donor, making a readmission much likelier.

When trying to compare the LLDN with the OLDN, we have to remember that there are inherent difficulties in any long-term comparison given that the laparoscopic procedure is evolving over time, both in terms of the patient selection, as well as in terms of the technical aspects. Regarding the latter, an example is the manner chosen to control the renal artery. In the first several cases we were using the self-locking plastic clips to ligate the artery prior to transecting it, with the main reason being that a better length on the artery can be obtained. Unfortunately, due to episodes of bleeding secondary to the clips falling off, we had to change to a different technique with the use of a vascular stapler to ligate the renal artery and vein, and inspect the stapler line before transecting the vessel. Our experience in this aspect appears to be similar to other centers, including a survey of all 893 surgeon-members of the American Society of Transplant Surgeons with a 24% response rate, which reported 66 and 39 episodes of arterial and venous hemorrhage, with two episodes of donor deaths due to bleeding and with the locking and standard clips applied to the renal artery being associated with a higher risk, and thus leading to warnings against their use[14,15]. Another issue is that of the use of the left or right donor kidney. Specifically, initially there was a preference for the left-sided kidney, given the concerns for vascular control and vessel length[16]. However, the combination of increased experience and the need to increase the living donor population to try to cover the existing need, and despite the technical difficulties, has led to significant efforts to perform right LLDN in the group of patients where left renal donation might not be ideal because of the anatomy or functional issues[17,18].

The question of using the left or the right kidney is part of a bigger issue having to do with choosing the right living donor. The basic elements of that are identifying a person who will be able to donate a kidney that is functioning well, while at the same time preserving the well-being of the donor throughout the whole process[19,20]. This has become even more critical as, given the success of living donation, there is increased pressure to include more high risk donors, such as those with obesity, older or younger donors, hypertensive donors, and those with preexisting conditions, such as kidney stones, that might affect the renal function post-donation[21-24]. Additionally, in the United States and in certain other countries there is also the existence of nondirected or altruistic donors or paired exchanges of living donors in the case of sensitized recipients or blood group issues[25,26]. All of the above stress the need for a living donor registry, where the goal would be to determine the collective experience regarding complications and long-term outcomes[9]. The advantages of this registry would be the ability to provide accurate outcome information to both donors and recipients, assist programs in assessing their results, identify problems in a timely fashion where intervention is possible, and increase public confidence in the process of donation[7]. There have been some efforts along these lines, such as the European Living Donation and Public Health (EULID) project, which included mandatory registration and follow-up data, as well as regular audits of the 11 nations that initially organized this effort[27].

One of the key points in our study is the importance of the learning curve, as we can see by the improvement in the operating time, as well as the decrease in the number of conversions. However, we have to understand that this also remains a continuously evolving matter, given the fact that the procedure itself is evolving with a significant number of variations on the surgical technique, such as the robotic nephrectomy, the natural orifice transluminal endoscopic surgery and single incision laparoscopic surgery using a single port[28-35]. These elements of progress should be embraced, while at the same time collecting all the necessary data to evaluate them fully in the long-term, with the primary consideration always being the welfare of the living donor. Another point having to do with the learning curve is the transfer of surgical knowledge and training. Specifically, in order to train the next generation of surgeons performing laparoscopic living donor nephrectomies, the attending performing the surgery needs to train the fellow, and potentially the general surgical resident. However, given the fact that there is no room for errors in the case of living donation, the best way to start is in the case of laparoscopic nephrectomies performed for other etiologies, such as malignancy or infection. This way the trainee can “graduate” to the more complex procedure. It is essential to remember that this is not a “standard” laparoscopic nephrectomy, given the fact that the care and accuracy during the donor kidney extraction will play a critical role in the subsequent function of this kidney. For these reasons, the surgeon needs to be cognizant of the relevant physiology, in addition to possessing surgical excellence.

In conclusion, there are limitations to this study. These include its retrospective nature, the fact that it is from a single center, as well as the time period of a decade that it spans. The latter point has to do with the changes in techniques and instrumentation which have occurred and which unfortunately represent a limitation of any study in such a rapidly evolving field of medicine and surgery. However, despite these limitations, the study has shown that LLDN can be as efficacious and at least as safe as OLDN, while at the same time offering the advantage of decreased length of stay and improved cosmesis, both of which can have a positive impact on potential living donors. We have seen the paramount importance of the learning curve, as well as the fact that this is an active process where lessons are continuously learnt, making it necessary to make adjustments to ensure the safety of the donor and the recipient. This evolving process makes it necessary for different centers to share their experience, ideally in the form of a donor registry, so that all can benefit from these lessons.

Progress in surgical technique and instrumentation has led to a significant increase of laparoscopic compared to open living donor nephrectomies (OLDN), based on patient and physician preferences.

Despite the evolution of laparoscopic or minimally invasive donor nephrectomy, there are still questions remaining regarding its efficacy and safety profile. Some of the reasons for this are the continuous evolution in surgical techniques and instruments (thus making comparisons more difficult), as well as issues of underreporting when it comes down to donor complications. This study aims to provide added evidence in this debate and to help clarify the role of laparoscopic living donor nephrectomy (LLDN).

In this study describing the experience of the Massachusetts General Hospital Transplant Division in the decade between 1998 and 2009 with OLDN and LLDN, the authors have seen that there is no difference regarding the efficacy and safety profile of the two procedures. The one statistically significant difference is the decreased length of stay seen with the laparoscopic LDN compared to the open. However, the most useful lesson is the importance of the learning curve, as that leads to the necessary technical excellence required.

This study adds to the existing evidence showing that laparoscopic or minimally invasive LDN has the potential to become the predominant surgical technique for renal living donation. This will undoubtedly also increase the popularity of the procedure for people considering donation, given the less “intrusive” nature of minimally invasive surgery.

Living donor nephrectomy: It is the surgical procedure whereby one of the kidneys of a living donor is removed (either in an open manner or with a minimally invasive procedure) and transplanted in a recipient.

The study is an interesting one. Clear writing and lucid illustrations get the message across well.

Manuscript source: Invited manuscript

Specialty type: Urology and nephrology

Country of origin: Greece

Peer-review report classification

Grade A (Excellent): A

Grade B (Very good): 0

Grade C (Good): C, C

Grade D (Fair): 0

Grade E (Poor): 0

P- Reviewer: Friedman EA, Trimarchi H, Taheri S S- Editor: Gong XM L- Editor: A E- Editor: Lu YJ

| 1. | Ratner LE, Ciseck LJ, Moore RG, Cigarroa FG, Kaufman HS, Kavoussi LR. Laparoscopic live donor nephrectomy. Transplantation. 1995;60:1047-1049. [PubMed] [Cited in This Article: ] |

| 2. | Wolf JS, Tchetgen MB, Merion RM. Hand-assisted laparoscopic live donor nephrectomy. Urology. 1998;52:885-887. [PubMed] [DOI] [Cited in This Article: ] [Cited by in Crossref: 168] [Cited by in F6Publishing: 175] [Article Influence: 6.7] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 3. | Slakey DP, Wood JC, Hender D, Thomas R, Cheng S. Laparoscopic living donor nephrectomy: advantages of the hand-assisted method. Transplantation. 1999;68:581-583. [PubMed] [DOI] [Cited in This Article: ] [Cited by in Crossref: 130] [Cited by in F6Publishing: 135] [Article Influence: 5.4] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 4. | Leventhal JR, Kocak B, Salvalaggio PR, Koffron AJ, Baker TB, Kaufman DB, Fryer JP, Abecassis MM, Stuart FP. Laparoscopic donor nephrectomy 1997 to 2003: lessons learned with 500 cases at a single institution. Surgery. 2004;136:881-890. [PubMed] [DOI] [Cited in This Article: ] [Cited by in Crossref: 103] [Cited by in F6Publishing: 88] [Article Influence: 4.4] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 5. | Su LM, Ratner LE, Montgomery RA, Jarrett TW, Trock BJ, Sinkov V, Bluebond-Langner R, Kavoussi LR. Laparoscopic live donor nephrectomy: trends in donor and recipient morbidity following 381 consecutive cases. Ann Surg. 2004;240:358-363. [PubMed] [DOI] [Cited in This Article: ] [Cited by in Crossref: 110] [Cited by in F6Publishing: 124] [Article Influence: 6.2] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 6. | Jacobs SC, Cho E, Foster C, Liao P, Bartlett ST. Laparoscopic donor nephrectomy: the University of Maryland 6-year experience. J Urol. 2004;171:47-51. [PubMed] [DOI] [Cited in This Article: ] [Cited by in Crossref: 200] [Cited by in F6Publishing: 183] [Article Influence: 9.2] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 7. | Living Kidney Donor Follow-Up Conference Writing Group, Leichtman A, Abecassis M, Barr M, Charlton M, Cohen D, Confer D, Cooper M, Danovitch G, Davis C, Delmonico F, Dew MA, Garvey C, Gaston R, Gill J, Gillespie B, Ibrahim H, Jacobs C, Kahn J, Kasiske B, Kim J, Lentine K, Manyalich M, Medina-Pestana J, Merion R, Moxey-Mims M, Odim J, Opelz G, Orlowski J, Rizvi A, Roberts J, Segev D, Sledge T, Steiner R, Taler S, Textor S, Thiel G, Waterman A, Williams E, Wolfe R, Wynn J, Matas AJ. Living kidney donor follow-up: state-of-the-art and future directions, conference summary and recommendations. Am J Transplant. 2011;11:2561-2568. [PubMed] [Cited in This Article: ] |

| 8. | Wright AD, Will TA, Holt DR, Turk TM, Perry KT. Laparoscopic living donor nephrectomy: a look at current trends and practice patterns at major transplant centers across the United States. J Urol. 2008;179:1488-1492. [PubMed] [DOI] [Cited in This Article: ] [Cited by in Crossref: 41] [Cited by in F6Publishing: 45] [Article Influence: 2.8] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 9. | Shokeir AA. Open versus laparoscopic live donor nephrectomy: a focus on the safety of donors and the need for a donor registry. J Urol. 2007;178:1860-1866. [PubMed] [DOI] [Cited in This Article: ] [Cited by in Crossref: 61] [Cited by in F6Publishing: 70] [Article Influence: 4.1] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 10. | Nanidis TG, Antcliffe D, Kokkinos C, Borysiewicz CA, Darzi AW, Tekkis PP, Papalois VE. Laparoscopic versus open live donor nephrectomy in renal transplantation: a meta-analysis. Ann Surg. 2008;247:58-70. [PubMed] [Cited in This Article: ] |

| 11. | Shafizadeh S, McEvoy JR, Murray C, Baillie GM, Ashcraft E, Sill T, Rogers J, Baliga P, Rajagopolan PR, Chavin K. Laparoscopic donor nephrectomy: impact on an established renal transplant program. Am Surg. 2000;66:1132-1135. [PubMed] [Cited in This Article: ] |

| 12. | Melcher ML, Carter JT, Posselt A, Duh QY, Stoller M, Freise CE, Kang SM. More than 500 consecutive laparoscopic donor nephrectomies without conversion or repeated surgery. Arch Surg. 2005;140:835-839; discussion 839-840. [PubMed] [DOI] [Cited in This Article: ] [Cited by in Crossref: 70] [Cited by in F6Publishing: 72] [Article Influence: 3.8] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 13. | Matas AJ, Bartlett ST, Leichtman AB, Delmonico FL. Morbidity and mortality after living kidney donation, 1999-2001: survey of United States transplant centers. Am J Transplant. 2003;3:830-834. [PubMed] [Cited in This Article: ] |

| 14. | Ahearn AJ, Posselt AM, Kang SM, Roberts JP, Freise CE. Experience with laparoscopic donor nephrectomy among more than 1000 cases: low complication rates, despite more challenging cases. Arch Surg. 2011;146:859-864. [PubMed] [DOI] [Cited in This Article: ] [Cited by in Crossref: 26] [Cited by in F6Publishing: 28] [Article Influence: 2.2] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 15. | Friedman AL, Peters TG, Jones KW, Boulware LE, Ratner LE. Fatal and nonfatal hemorrhagic complications of living kidney donation. Ann Surg. 2006;243:126-130. [PubMed] [DOI] [Cited in This Article: ] [Cited by in Crossref: 135] [Cited by in F6Publishing: 145] [Article Influence: 8.1] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 16. | Dols LF, Kok NF, Alwayn IP, Tran TC, Weimar W, Ijzermans JN. Laparoscopic donor nephrectomy: a plea for the right-sided approach. Transplantation. 2009;87:745-750. [PubMed] [DOI] [Cited in This Article: ] [Cited by in Crossref: 47] [Cited by in F6Publishing: 53] [Article Influence: 3.5] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 17. | Keller JE, Dolce CJ, Griffin D, Heniford BT, Kercher KW. Maximizing the donor pool: use of right kidneys and kidneys with multiple arteries for live donor transplantation. Surg Endosc. 2009;23:2327-2331. [PubMed] [DOI] [Cited in This Article: ] [Cited by in Crossref: 31] [Cited by in F6Publishing: 34] [Article Influence: 2.3] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 18. | Tsoulfas G, Agorastou P, Ko D, Hertl M, Elias N, Cosimi AB, Kawai T. Laparoscopic living donor nephrectomy: is there a difference between using a left or a right kidney? Transplant Proc. 2012;44:2706-2708. [PubMed] [DOI] [Cited in This Article: ] [Cited by in Crossref: 15] [Cited by in F6Publishing: 16] [Article Influence: 1.5] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 19. | Mandelbrot DA, Pavlakis M, Danovitch GM, Johnson SR, Karp SJ, Khwaja K, Hanto DW, Rodrigue JR. The medical evaluation of living kidney donors: a survey of US transplant centers. Am J Transplant. 2007;7:2333-2343. [PubMed] [DOI] [Cited in This Article: ] [Cited by in Crossref: 224] [Cited by in F6Publishing: 205] [Article Influence: 12.1] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 20. | Rodrigue JR, Pavlakis M, Danovitch GM, Johnson SR, Karp SJ, Khwaja K, Hanto DW, Mandelbrot DA. Evaluating living kidney donors: relationship types, psychosocial criteria, and consent processes at US transplant programs. Am J Transplant. 2007;7:2326-2332. [PubMed] [DOI] [Cited in This Article: ] [Cited by in Crossref: 110] [Cited by in F6Publishing: 112] [Article Influence: 6.6] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 21. | Cherikh WS, Young CJ, Kramer BF, Taranto SE, Randall HB, Fan PY. Ethnic and gender related differences in the risk of end-stage renal disease after living kidney donation. Am J Transplant. 2011;11:1650-1655. [PubMed] [DOI] [Cited in This Article: ] [Cited by in F6Publishing: 1] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 22. | Reese PP, Feldman HI, McBride MA, Anderson K, Asch DA, Bloom RD. Substantial variation in the acceptance of medically complex live kidney donors across US renal transplant centers. Am J Transplant. 2008;8:2062-2070. [PubMed] [DOI] [Cited in This Article: ] [Cited by in F6Publishing: 1] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 23. | Lentine KL, Schnitzler MA, Xiao H, Saab G, Salvalaggio PR, Axelrod D, Davis CL, Abbott KC, Brennan DC. Racial variation in medical outcomes among living kidney donors. N Engl J Med. 2010;363:724-732. [PubMed] [DOI] [Cited in This Article: ] [Cited by in Crossref: 235] [Cited by in F6Publishing: 237] [Article Influence: 16.9] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 24. | Nogueira JM, Weir MR, Jacobs S, Breault D, Klassen D, Evans DA, Bartlett ST, Cooper M. A study of renal outcomes in obese living kidney donors. Transplantation. 2010;90:993-999. [PubMed] [DOI] [Cited in This Article: ] [Cited by in Crossref: 53] [Cited by in F6Publishing: 57] [Article Influence: 4.1] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 25. | Matas AJ, Garvey CA, Jacobs CL, Kahn JP. Nondirected donation of kidneys from living donors. N Engl J Med. 2000;343:433-436. [PubMed] [DOI] [Cited in This Article: ] [Cited by in Crossref: 122] [Cited by in F6Publishing: 129] [Article Influence: 5.4] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 26. | Gentry SE, Montgomery RA, Swihart BJ, Segev DL. The roles of dominos and nonsimultaneous chains in kidney paired donation. Am J Transplant. 2009;9:1330-1336. [PubMed] [DOI] [Cited in This Article: ] [Cited by in F6Publishing: 1] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 27. | Manyalich M, Ricart A, Martínez I, Balleste C, Paredes D, Vilardell J, Avsec D, Dias L, Fehrman-Eckholm I, Hiesse C. EULID project: European living donation and public health. Transplant Proc. 2009;41:2021-2024. [PubMed] [DOI] [Cited in This Article: ] [Cited by in Crossref: 18] [Cited by in F6Publishing: 19] [Article Influence: 1.4] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 28. | Gill IS, Canes D, Aron M, Haber GP, Goldfarb DA, Flechner S, Desai MR, Kaouk JH, Desai MM. Single port transumbilical (E-NOTES) donor nephrectomy. J Urol. 2008;180:637-641; discussion 641. [PubMed] [Cited in This Article: ] |

| 29. | John Hopkins Medical Institutions. Healthy Kidney Removed Through Donor’s Vagina 2009. [accessed 2015 Jul 10]. Available from: http://esceincenews.com/articles/2009/02/02/hopkins.transplant.surgeons.remove.healthy.kidney.through.donors.vagina. [Cited in This Article: ] |

| 30. | Olakkengil SA, Rao MM. Evolution of minimally invasive surgery for donor nephrectomy and outcomes. JSLS. 2011;15:208-212. [PubMed] [DOI] [Cited in This Article: ] [Cited by in Crossref: 2] [Cited by in F6Publishing: 3] [Article Influence: 0.2] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 31. | Mahid SS, Hornung CA, Minor KS, Turina M, Galandiuk S. Systematic reviews and meta-analysis for the surgeon scientist. Br J Surg. 2006;93:1315-1324. [PubMed] [Cited in This Article: ] |

| 32. | Oxman AD. Checklists for review articles. BMJ. 1994;309:648-651. [PubMed] [DOI] [Cited in This Article: ] [Cited by in Crossref: 293] [Cited by in F6Publishing: 291] [Article Influence: 9.7] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 33. | Horgan S, Benedetti E, Moser F. Robotically assisted donor nephrectomy for kidney transplantation. Am J Surg. 2004;188:45S-51S. [PubMed] [Cited in This Article: ] |

| 34. | Hubert J, Renoult E, Mourey E, Frimat L, Cormier L, Kessler M. Complete robotic-assistance during laparoscopic living donor nephrectomies: an evaluation of 38 procedures at a single site. Int J Urol. 2007;14:986-989. [PubMed] [DOI] [Cited in This Article: ] [Cited by in F6Publishing: 1] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 35. | Renoult E, Hubert J, Ladrière M, Billaut N, Mourey E, Feuillu B, Kessler M. Robot-assisted laparoscopic and open live-donor nephrectomy: a comparison of donor morbidity and early renal allograft outcomes. Nephrol Dial Transplant. 2006;21:472-477. [PubMed] [DOI] [Cited in This Article: ] [Cited by in Crossref: 45] [Cited by in F6Publishing: 50] [Article Influence: 2.6] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |