Published online Sep 10, 2018. doi: 10.5500/wjt.v8.i5.178

Peer-review started: May 3, 2018

First decision: May 22, 2018

Revised: June 14, 2018

Accepted: June 28, 2018

Article in press: June 28, 2018

Published online: September 10, 2018

To evaluate the role of a therapeutic regimen with plasma exchange, intravenous immunoglobulins and rituximab in chronic-active antibody-mediated rejection (cAMR) settings.

We compared 21 kidney transplant recipients (KTRs) with a diagnosis of cAMR in a retrospective case-control analysis: nine KTRs treated with plasmapheresis, intravenous immunoglobulins and rituximab (PE-IVIG-RTX group) vs 12 patients (control group) not treated with antibody-targeted therapies. We examined kidney survival and functional outcomes 24 mo after diagnosis. Histological features and donor-specific antibody (DSA) characteristics (MFI and C1q-fixing ability) were also investigated.

No difference in graft survival between the two groups was noted: three out of nine patients in the PE-IVIG-RTX group (33.3%) and 4/12 in the control group (33.3%) experienced loss of allograft function at a median time after diagnosis of 14 mo (min 12-max 18) and 15 mo (min 7-max 22), respectively. Kidney functional tests and proteinuria 24 mo after cAMR diagnosis were also similar in both groups. Only microvascular inflammation (glomerulitis + peritubular capillaritis score) was significantly reduced after PE-IVIG-RTX in seven out of eight patients (87.5%) in the PE-IVIG-RTX group (median score 3 in pre-treatment biopsy vs 1.5 in post-treatment biopsy; P = 0.047), without any impact on kidney survival and/or DSA characteristics. No functional or histological parameter at diagnosis was predictive of clinical outcome.

Our data showed no difference in the two year post-treatment outcome of kidney grafts treated with PE-IVIG-RTX for cAMR diagnosis, however there were notable improvements in microvascular inflammation in post-therapy protocol biopsies. Further studies, especially involving innovative therapeutic approaches, are required to improve the management and long-term results of this severe condition.

Core tip: Chronic-active antibody-mediated rejection (cAMR) is one of the major causes of poor long-term outcome in kidney transplantation, with no effective treatments currently available. We retrospectively compared 21 kidney transplant recipients with a diagnosis of cAMR, nine treated with plasmapheresis, intravenous immunoglobulins and rituximab vs 12 patients not treated with antibody-targeted therapies. Our data showed improvement in microvascular inflammation in post-therapy protocol biopsies without differences in functional outcomes at 24 mo, suggesting the lack of a prompt and marked effect of this therapeutic protocol. Further studies are required to improve the management and long-term results of this severe condition.

- Citation: Mella A, Gallo E, Messina M, Caorsi C, Amoroso A, Gontero P, Verri A, Maletta F, Barreca A, Fop F, Biancone L. Treatment with plasmapheresis, immunoglobulins and rituximab for chronic-active antibody-mediated rejection in kidney transplantation: Clinical, immunological and pathological results. World J Transplantation 2018; 8(5): 178-187

- URL: https://www.wjgnet.com/2220-3230/full/v8/i5/178.htm

- DOI: https://dx.doi.org/10.5500/wjt.v8.i5.178

Chronic-active antibody-mediated rejection (cAMR) due to de novo or pre-formed donor specific antibody (DSA) is currently considered the main cause of long-term allograft losses[1,2].

From the first pilot test with intravenous immunoglobulins (IVIG) and rituximab (RTX) reported by Billing et al[3], based on the aim of reducing or eliminating DSA, some authors antagonized their detrimental effects on the graft and proposed different therapeutic regimens for cAMR treatment. All of these protocols were derived from previous experience using acute antibody-mediated rejection and desensitization protocols, and mainly consisted of steroids, plasma exchange (PE), IVIG and RTX in various modalities[4-7]. More recently, bortezomib and eculizumab were also proposed[8-10].

Specifically, an antibody-directed treatment combining high-dose IVIG and RTX showed beneficial effects [reduction in allograft losses and/or stabilization of glomerular filtration rate (GFR)] in some patients with cAMR[3-5,11], but these positive results have now been partially questioned[12-15].

The role of functional and histological parameters (i.e., GFR proteinuria at diagnosis, microvascular inflammation) in predicting response to antibody-targeted therapy has also been evaluated[6,16].

In spite of the aforementioned studies, the question of when these protocols should be adopted (in all patients or in only specific histopathological and functional settings) is still open.

In our Transplantation Center, we adopted a therapeutic protocol from 2011 that includes PE, IVIG and RTX in patients with a diagnosis of cAMR. In this paper, we compare, in a retrospective case-control analysis, nine patients treated with a combination of PE, IVIG and RTX (PE-IVIG-RTX group) for cAMR with a historical cohort of 12 kidney transplant recipients (KTRs) (control group). These control patients displayed similar histological and clinical profiles to the experimental patients, however they were not treated with antibody-targeted therapies. The primary outcome of our analysis was the difference in graft survival at 12 and 24 mo following diagnosis. Renal functional tests (including proteinuria), changes in histological features and/or DSAs-MFI, and C1q-binding ability were considered as secondary endpoints.

Twenty-one adult KTRs with a diagnosis of cAMR according to the BANFF 2015 criteria (see Histology section) were included in this retrospective study. These 21 patients included nine with a consecutive diagnosis of cAMR from January 1, 2011 to December 31, 2014 who were treated with PE, IVIG and RTX (PE-IVIG-RTX group), and 12 KTRs with the same consecutive diagnosis performed in the period between January 2009 and December 2012 (control group). In that early period, antibody-targeted therapies were not currently adopted, or patients did not give their consent to these therapies.

At the time of diagnosis, patients were treated with a CNI-based immunosuppression (28.6% Cyclosporine A, 71.4% Tacrolimus, equally distributed into two groups), with Mycophenolate Mofetil/Mycophenolic Acid (77.8% in the PE-IVIG-RTX group and 66.7% in the control group) or an mTOR inhibitor drug (11.1% in the PE-IVIG-RTX group and 37.3% in the control group). Azathioprine was used only in one patient in the PE-IVIG-RTX group, and 77.8% of patients in the PE-IVIG-RTX group vs 66.7% in the control group were treated with steroids, respectively.

After cAMR diagnosis, maintenance therapy was reinforced in both groups by either introducing MMF and/or steroids, (with contemporary suspension of the mTOR inhibitor drug, if used) or switching from Cyclosporine A to Tacrolimus.

The PE-IVIG-RTX schedule was defined as follows: (1) Four or five PE (one plasma volume removal and 5% Albumin or plasma infusion) sessions in the first two weeks, (2) subsequent high-dose 2 g/kg IVIG (in one or two days), and (3) intravenous RTX (375 mg/m2, one dose) after IVIG. Three patients in both groups also received steroid boluses after diagnosis (4 mg/kg methylprednisolone, tapered in five to seven days with a total steroid dose of about 1.5 g). One patient in the PE-IVIG-RTX group received a second RTX dose (375 mg/m2) because of a concomitant diagnosis of membranous nephropathy.

Renal function was measured by serum creatinine (sCr) and GFR (estimated using the Cockroft-Gault formula). Patients were also tested repeatedly pre-transplantation for anti-HLA antibodies using the panel reactive lymphocytotoxicity assay, and maximum values from this assay were considered for our analysis.

We obtained an informed consent about potential complications and adverse events from all treated patients.

All biopsies were performed for cause, i.e., in case of a significant and/or unexplained increase of serum creatinine > 25% from baseline, proteinuria, or both. Biopsies were reviewed according to the Banff 2015 classification[17], and only patients with a diagnosis of cAMR meeting all the requested criteria were included in this study. These criteria are as follows: (1) Histologic evidence of chronic tissue injury (transplant glomerulopathy - expressed by a cg score > 0, and/or severe peritubular capillary basement membrane multilayering, and/or arterial intimal fibrosis of new onset; (2) evidence of antibody-endothelium interaction [C4d > 0 in paraffin sections of peritubular capillaries and/or microvascular inflammation (MVI) – expressed by a g + ptc score ≥ 2, considering that in the presence of acute TCMR, borderline infiltrate, or infection, g must be ≥ 1]; and (3) serologic evidence of DSAs. We also evaluated a chronicity score (ci + ct), as reported by other authors[18].

In the PE-IVIG-RTX group, we also performed a protocol kidney biopsy at a median time of ten months after therapy (as discussed below in the Results section) in order to assess histopathological improvement when present.

Sera were evaluated twice, at both the time of biopsy and after 12 mo. As discussed in our previous paper[19], we tested all sera with a Luminex platform and commercially-available SAB kits (LABScreen One Lambda, Canoga Park, CA, United States) in order to identify HLA Classes I and II IgG DSA. Sera were also studied with the C1qScreen (One Lambda) to assess DSA complement-fixing ability. The cut-off was set at the normalized MFI value of 1000 for both tests.

Statistical analysis was performed with SPSS (IBM SPSS Statistics, vers. 22.0.0). Continuous variables are presented, according to their distribution, as mean ± SD or as median (min-max). Inter-group differences were analysed with t-test or Mann-Whitney test, respectively. We expressed categorical variables as fractions, and Pearson’s χ2 or, for small samples, Fisher’s exact test was adopted to compare groups. The odds ratios (OR) with 95%CI were used as a measure of relative risk. Survival analysis was performed with the Kaplan-Meier method, comparing groups with Log Rank test. Significance level (α) was set at P < 0.05 for all tests.

The PE-IVIG-RTX and control groups are comparable (P = NS) for the time between transplantation and cAMR diagnosis, age at diagnosis, donor age, immunosuppressive therapy (induction and maintenance), number of mismatches and previous episodes of acute rejection (acute AMR and acute cellular rejection). In addition, the evaluation of renal functional tests (sCr, GFR) and proteinuria showed no difference between the two groups at diagnosis (Table 1).

| PE-IVIG-RTX group (n = 9) | Control group (n = 12) | P-value | |

| Recipient age at diagnosis, yr | 47 (24-65) | 52 (26-67) | 0.234 |

| Gender (M/F ratio) | 5/4 | 8/4 | 0.604 |

| Donor age, yr | 58 (37-80) | 49 (18-82) | 0.203 |

| Living donor transplantation | 2/9 (22.2) | 0/12 (0) | 0.086 |

| Previous transplants | 1/9 (11.1) | 3/12 (25) | 0.422 |

| Maximum PRA | 0% (0-89) | 27.5% (0-95) | 0.061 |

| Mismatches HLA A-B-DR, n | 2 (1-4) | 3 (1-4) | 0.639 |

| Previous episodes of acute rejection | |||

| (acute AMR – ACR) | 1/9 (11.1)-1/9 (11.1) | 1/12 (8.3)-1/12 (8.3) | 0.586 |

| Immunosuppression: Induction1 | 9/9 (100) | 10/12 (83.3) | 0.198 |

| Clinical data at diagnosis | |||

| Time between transplantation and diagnosis of cAMR, mo | 51 (21-108) | 79 (20-258) | 0.201 |

| Serum creatinine, mg/dL | 1.9 (1.2-3) | 1.9 (0.9-3.7) | 0.477 |

| GFR2, mL/min | 55,4 (23.9-65.4) | 42.35 (18.9-88.1) | 0.887 |

| Proteinuria, g/d | 1.6 (1-4) | 1.55 (0.3-7.3) | 0.886 |

Two out of nine patients (22.2%) in the PE-IVIG-RTX group and 6/12 (50%) in the control group expressed antibodies towards class I HLA. In 5/9 (55.6%) and 2/12 (16.7%), respectively, only anti class II HLA antibodies were found. Two out of nine patients (22.2%) in the PE-IVIG-RTX group and 4/12 (33.3%) in the control group showed both anti-class I and anti-class II HLA DSA (P = 0.166 for the analysis of distribution) (Table 2).

Considering the immunodominant antibody (DSA with the higher MFI), the median MFI was similar between the two groups (9800 in the PE-IVIG-RTX group vs 4500 in the control group, P = 0.327). Additionally, C1q-fixing ability showed no difference in the two populations: 4/9 patients (44.4%) in the PE-IVIG-RTX group and 4/10 (40%) in the control group expressed a C1q-fixing DSA ability (two patients were not tested for serum unavailability).

Considering the whole population, the median MFI was higher in patients with C1q-fixing DSA (median 15000, min 4700 - max 24700) in comparison with patients with non-C1q-fixing DSA (median 3000, min 900 - max 13400; P = 0.010).

Assessing cAMR histological scores according to the BANFF 2015 criteria[17] at diagnosis, the two populations were comparable for all of the considered variables: chronic glomerulopathy (cg), glomerulitis (g), peritubular capillaritis (ptc), microvascular inflammation (MVI) score (g + ptc), interstitial inflammation (ci), C4d positivity, and C4d score. Only tubular atrophy (ct) was statistically different between the PE-IVIG-RTX and control groups (median score 0, min 0 - max 1 vs 1, min 0 - max 1, respectively; P = 0.04). This was in spite of the chronicity composite score (ci + ct), which was quite similar in both groups (1, min 0 - 3 in the PE-IVIG-RTX group vs 2, min 0 - max 3 in the control group; P = 0.831) (Table 3).

| PE-IVIG-RTX group (n = 9) | Control group (n = 12) | P-value | |

| Chronic glomerulopathy (cg) | 2 (1-3) | 1.5 (0-3) | 0.792 |

| Glomerulitis (g) | 2 (1-3) | 2 (0-3) | 0.23 |

| Peritubular capillaritis (ptc) | 1 (0-2) | 0.5 (0-3) | 0.122 |

| Microvascular inflammation (g + ptc) | 3 (2-5) | 2.5 (2-3) | 0.219 |

| Interstitial inflammation (ci) | 1 (0-3) | 1 (0-2) | 0.624 |

| Tubular atrophy (ct) | 0 (0-1) | 1 (0-1) | 0.04 |

| Chronicity score (ci + ct) | 1 (0-3) | 2 (0-3) | 0.497 |

| Arteriolar hyaline thickening (ah) | 2 (0-3) | 2 (0-3) | 0.075 |

| C4d+, n (%) | 7/9 (77.8) | 7/12 (58.3) | 0.35 |

| C4d score | 2 (0-3) | 1 (0-3) | 0.831 |

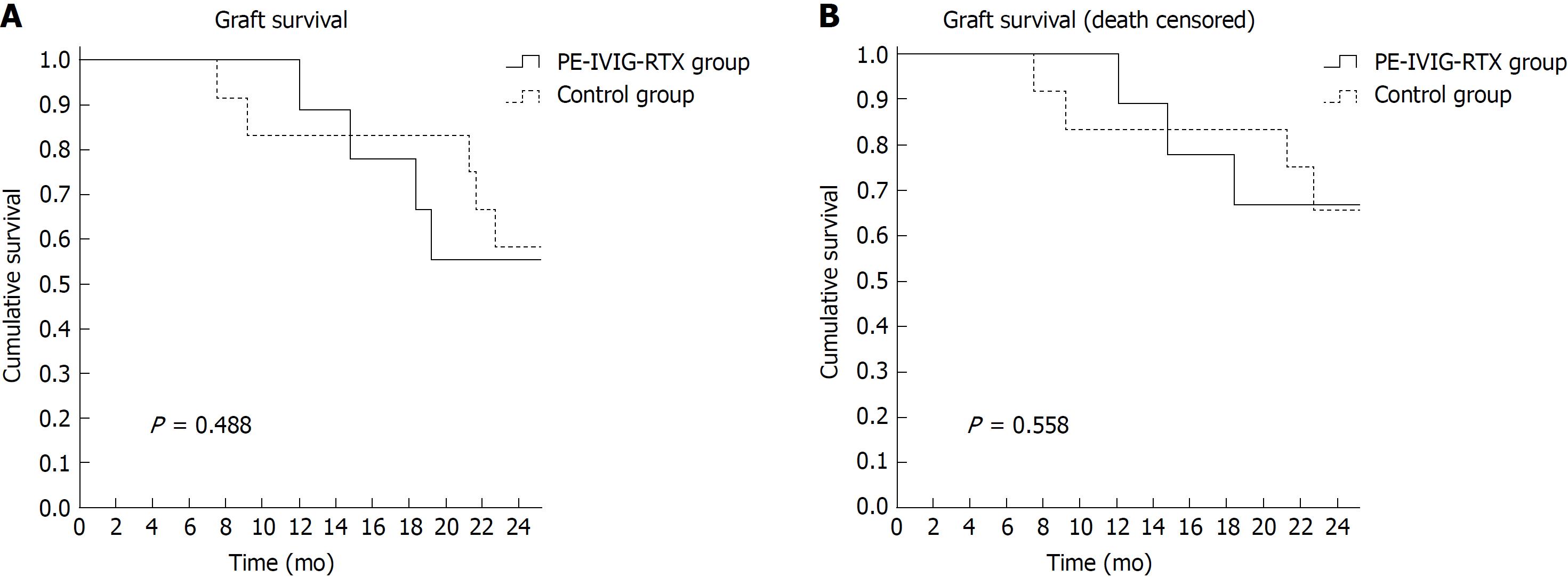

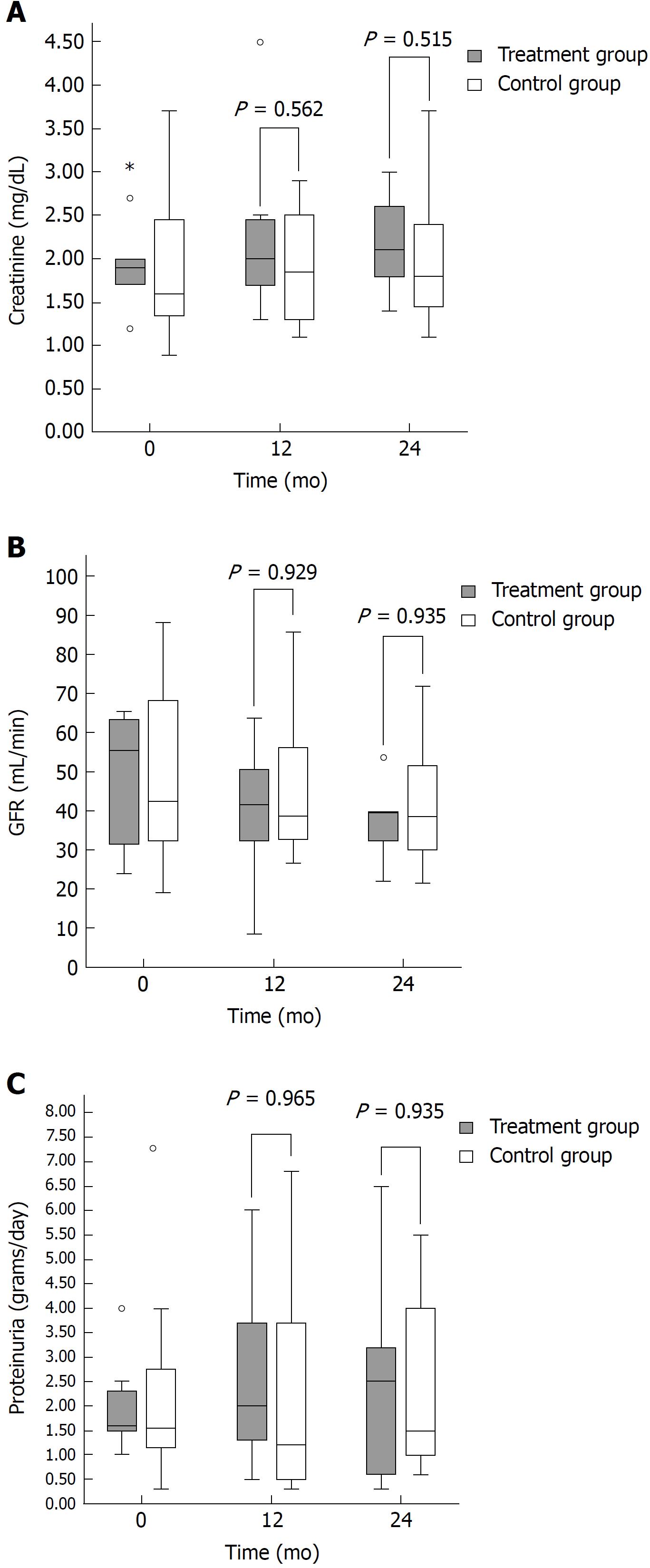

No difference in graft survival was noted 12 and 24 mo after cAMR diagnosis. At the end of the follow-up, five out of the nine patients in the PE-IVIG-RTX group (55.6%) and 7/12 (58.3%) in the control group had a functioning graft (Figure 1A). Three out of nine patients in the PE-IVIG-RTX group (33.3%) and 4/12 in the control group lost their allograft, at a median time after diagnosis of 14 mo (min 12 - max 18) and 15 mo (min 7 - max 22), respectively. One patient in both the PE-IVIG-RTX group and control group died with a functioning graft, and the adjusted death-censored graft survival remained similar between the PE-IVIG-RTX and control groups (Figure 1B, P = 0.558). Considering kidney functional tests (Figure 2A and B) and proteinuria (Figure 2C) in patients with a functioning graft, no difference was observed between the two groups at 12 and 24 mo (Figures 1 and 2).

Eight out of nine patients in the PE-IVIG-RTX group were subjected to a protocol biopsy at a median time of 10 mo (min 4 - max 20). We observed (Table 4) a significant reduction in MVI score in 7/8 (87.5%) of patients (median score 3 in pre-treatment biopsy vs 1.5 in post-treatment biopsy, P = 0.047); a trend in the reduction of C4d positivity was also noted (7/9 - 77.8% in pre-treatment biopsy vs 3/8 - 37.5% in post-treatment biopsy, P = 0.083), without differences in pre- and post-treatment cg and chronicity score (Tables 4 and 5).

| Pre PE-IVIG-RTX (n = 9) | Post PE-IVIG-RTX (n = 8) | P-value | |

| Chronic glomerulopathy (cg) | 2 (1-3) | 2 (1-3) | 0.705 |

| Glomerulitis (g) | 2 (1-3) | 0.5 (0-2) | 0.054 |

| Peritubular capillaritis (ptc) | 1 (0-2) | 0.5 (0-2) | 0.160 |

| Microvascular inflammation (g + ptc) | 3 (2-5) | 1.5 (0-4) | 0.047 |

| Interstitial inflammation (ci) | 1 (0-3) | 1 (1-3) | 0.480 |

| Tubular atrophy (ct) | 0 (0-1) | 1 (0-2) | 0.059 |

| Chronicity score (ci + ct) | 1 (0-3) | 2 (1-5) | 0.084 |

| C4d+, n (%) | 7/9 (77.8) | 3/8 (37.5) | 0.083 |

| C4d score | 2 (0-3) | 0 (0-3) | 0.102 |

| Immunodominant DSA specificity | Pre PE-IVIG-RTX (n = 9) | Post PE-IVIG-RTX (n = 8) | |||

| MFI | C1q-fixing | MFI | C1q-fixing | ||

| Patient 1 | DPw3 | 13400 | No | 8200 | Yes |

| Patient 2 | DQ9 | 3000 | No | 10300 | No |

| Patient 3 | A24 | 9800 | Yes | 21200 | No |

| Patient 4 | DR4 | 2700 | No | 0 | No |

| Patient 5 | B35 | 10300 | No | 2500 | No |

| Patient 6 | DQ5 | 7000 | Yes | 0 | No |

| Patient 7 | DR53 | 15000 | Yes | 24000 | Yes |

| Patient 8 | DQ7 | 24400 | Yes | 9000 | Yes |

| Patient 9 | DR51 | 7400 | No | 3400 | No |

| Median (min-max) | 9800 (2700-24400)1 | 4/92 | 8200 (0-24000)1 | 3/92 | |

Considering DSAs (Table 5), two out of nine patients (Pt. 4 and 6) had a negative post-treatment Luminex test. Despite the response in these two patients, considering the entire cohort, median MFI (9800 pre-treatment vs 8200 post-treatment; p = NS) and the percentage of C1q-fixing ability (4/9 - 44.4% pre-treatment vs 3/9 - 33.3% post-treatment) were unchanged after treatment.

To investigate whether some factors could be considered risk-prone for kidney failure, we analyzed both histological and clinical parameters at diagnosis.

Considering histopatological features (Table 6), no significant difference in cg and microvascular inflammation scores (g, ptc, g + ptc) or C4d positivity was observed between patients with functioning and non-functioning grafts at 24 mo in the PE-IVIG-RTX group, despite the fact that patients with non-functioning grafts showed a trend towards a more pronounced chronicity score at diagnosis (median 0.5 in patients with functioning grafts vs 2 in patients with non-functioning grafts; P = 0.29). Patients with a functioning graft in the control group showed a significantly higher g score (median 2 vs 1; P = 0.043) and lower ptc score (median 0 vs 1; P = 0.037), however the MVI score was quite similar in the two subgroups (median 2.5 in both subgroups; P = 0.727).

| PE-IVIG-RTX group(n = 9) | P-value | Control group(n = 12) | P-value | |||

| Functioninggraft(n = 6) | Non-functioning graft(n = 3) | Functioninggraft(n = 8) | Non-functioning graft(n = 4) | |||

| Chronic glomerulopathy (cg) | 2.5 (1-3) | 1 (1-3) | 0.57 | 2.5 (1-3) | 1 (0-2) | 0.226 |

| Glomerulitis (g) | 2 (1-3) | 1 (1-3) | 0.472 | 2 (2-3) | 1 (0-2) | 0.043 |

| Peritubular capillaritis (ptc) | 1 (0-2) | 1 (0-2) | 0.829 | 0 (0-1) | 1 (1-3) | 0.037 |

| Microvascular inflammation (g + ptc) | 2.5 (2-5) | 3 (2-3) | 0.269 | 2.5 (2-3) | 2.5 (2-3) | 0.727 |

| Interstitial inflammation (ci) | 0.5 (0-2) | 2 (1-2) | 0.131 | 1 (0-1) | 1 (1-2) | 0.852 |

| Tubular atrophy (ct) | 0 (0-1) | 0 (0-0) | 0.667 | 1 (0-1) | 1 (1-1) | 0.255 |

| Chronicity score (ci + ct) | 0.5 (0-2) | 2 (1-3) | 0.29 | 1.5 (0-3) | 2 (1-3) | 0.807 |

| C4d+, n (%) | 5/7 (71.4) | 2/3 (66.7) | 0.583 | 3/8 (37.5) | 4/4 (100) | 0.071 |

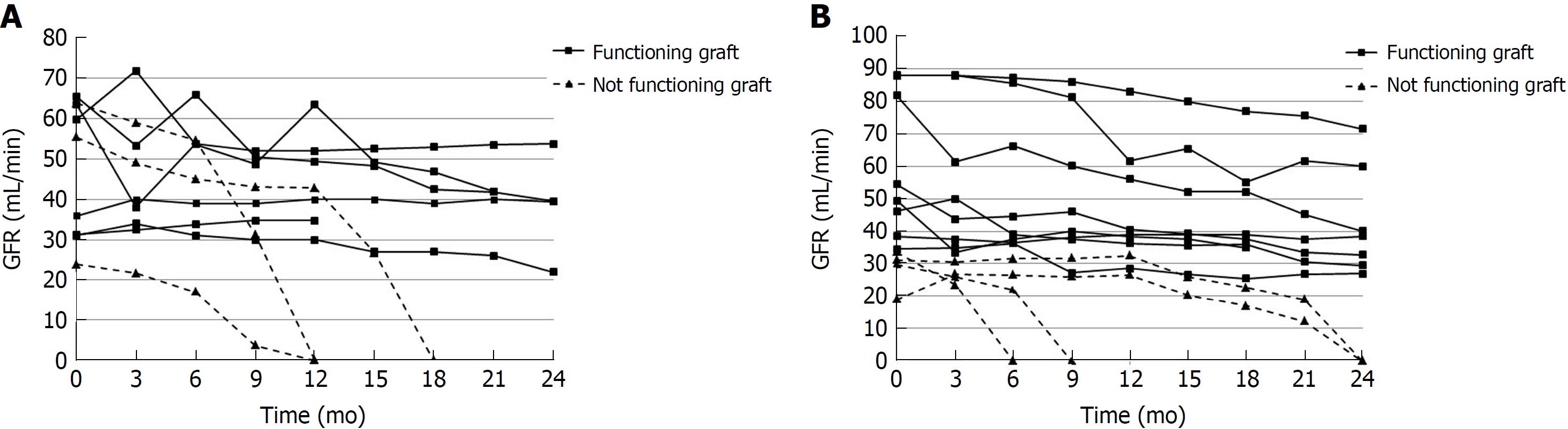

Kidney functional tests showed different patterns in the two groups (Table 7 and Figure 3). Data were examined at biopsy time. Proteinuria values were similar in all subgroups. sCr and GFR were comparable in patients with functioning and non-functioning grafts in the PE-IVIG-RTX group (Figure 3A and Table 7). On the contrary, functional data were significantly lower in patients with non-functioning vs functioning grafts at 24 mo in only the control group (median sCr 2.9 vs 1.4 mg/dL; P = 0.04 - median GFR 30.5 vs 52 mL/min; P = 0.04) (Figure 3B and Table 7).

| PE-IVIG-RTX group(n = 9) | P-value | Control group(n = 12) | P-value | |||

| Functioninggraft(n = 6) | Non-functioning graft(n = 3) | Functioninggraft(n = 8) | Non-functioninggraft(n = 4) | |||

| Creatinine, mg/dL | 1.75 (1.2-2.7) | 2 (1.9-3) | 0.167 | 1.4 (0.9-2.3) | 2.9 (2.4-3.7) | 0.04 |

| GFR, mL/min | 47.9 (31-65.4) | 55.4 (23.9-63.8) | 0.905 | 52 (34.5-88.1) | 30.5 (18.9-33.6) | 0.04 |

| Proteinuria, g/d | 1.55 (1.3-2.5) | 1.8 (1-4) | 0.905 | 1.7 (0.8-7.3) | 1.1 (0.3-2.6) | 0.154 |

| Donor age, yr | 61 (37-63) | 44 (43-80) | 0.796 | 50.5 (18-82) | 48 (25-55) | 0.799 |

| MFI | 11600 (2700-24400) | 7400 (7000-10300) | 0.714 | 4500 (900-19300) | 13200 (1700-24700) | 0.533 |

| C1q-fixing DSA, n (%) | 3/6 (50) | 1/3 (33.3) | 0.595 | 2/7(28.6) | 2/3(66.7) | 0.333 |

The donor age was similar between failed and unfailed grafts in both groups (Table 7). Despite patients with functioning and non-functioning grafts in the PE-IVIG-RTX group, DSA characteristics were comparable for MFI and C1q-fixing ability. In the control group, patients with non-functioning grafts showed a trend towards a higher MFI and C1q-fixing ability when compared with patients who had functioning grafts (median MFI 13200 vs 4500; P = 0.533 - C1q-fixing DSA in 2/3 vs 2/7; P = 0.333) (Table 7).

In the 24 mo follow-up after cAMR diagnosis, two patients died: one in the control group due to pulmonary cancer, and one in the PE-IVIG-RTX group due to a cardiovascular complication that occurred 19 mo after diagnosis and cAMR treatment. Four patients in the PE-IVIG-RTX group experienced five clinically-relevant bacterial infections (all recovered after appropriate treatments). No such infections were recorded in the control group (P = 0.03; Odds ratio for bacterial infection in the PE-IVIG-RTX group = 4, 1.7-9.3) (Table 8).

| PE-IVIG-RTX group (n = 9) | Control group (n = 12) | |

| Infections | ||

| Pyelonephritis and urinary tract infections | 1 | 0 |

| Gastrointestinal (diarrhea, ileitis) | 2 | 0 |

| Respiratory infection (bronchiolitis) | 1 | 0 |

| Acute cholecystitis | 1 | 0 |

| Cancers | 0 | 2 |

| Death | 1 | 1 |

In this study, we performed retrospective case-control analysis to study the mid-term clinical outcomes (24 mo) in 21 KTRs with a diagnosis of cAMR. We compared nine patients treated with PE, IVIG and RTX with a historical cohort of 12 patients who featured similar clinical and histological characteristics yet did not receive these antibody-targeted therapies.

Our data showed no clinical improvement after therapy with PE-IVIG-RTX, either in graft survival or in renal functional tests. In addition, proteinuria values were not influenced by the treatment.

On the contrary, upon evaluating histological features in protocol biopsies after PE-IVIG-RTX, microvascular inflammation (estimated by g + ptc score) was found to improve after PE-IVIG-RTX treatment. These data are quite similar to what was observed in the RITUX-ERAH trial in patients with acute AMR who were treated with PE, IVIG and steroids, either in association or not in association with RTX[18]. In Muller’s paper[15], patients treated for cAMR with only Rituximab improved in g + ptc score after one year. Despite different histological settings (acute AMR in tge RITUX-ERAH trial vs cAMR in our study and in Muller et al[15]) and different follow-ups (12 mo in the RITUX-ERAH trial and in Muller et al[15] vs 24 mo in our study), the evidence for an improvement in renal histology was not supported by an amelioration in kidney survival at a mid-term follow-up.

As for DSA, a lowering effect was not obtained in all patients (the median value was unchanged after treatment). These data may suggest that, in the context of chronic antibody production, the B cell target for PE-IVIG-RTX may elude the RTX effect and is likely represented by CD20-negative cells, as previously reported by other authors[12,20]. In two patients, we observed no DSA detection after treatment, although this was in association with highly different functional data (stabilization of GFR in one patient, graft failure in the other one).

No significant difference was noted in pre- and post-treatment C1q-fixing ability, or in DSA fixing complement ability at diagnosis. In addition, the clinical outcomes were similar at 24 mo. Our analysis is underpowered for the evaluation of DSA C1q-fixing ability as a marker of severe cAMR, which was positively reported in a larger cohort study[21]; however, we have recently observed in 35 KTRs with a transplant glomerulopathy diagnosis and de novo DSA (dnDSA) that a higher percentage of patients with dnDSA-associated transplant glomerulopathy was C1q-negative, and that the presence of C1q-fixing dnDSA did not significantly correlate with graft outcome19.

We are aware that the lack of difference in the immunodominant DSA-MFIs before and after treatment may be due to technical limitations related to the “prozone” effect[22]. However, it is remarkable that the MFI titer in three patients increased after treatment and that in 6/9 it remained higher than 3000, a threshold value considered by several centers.

We also evaluated functional, histological and immunological parameters at diagnosis to detect potential risk factors for allograft loss. In the control group, we found a trend towards a higher DSA-MFI titer, C1q-fixing DSA positivity, a higher sCr, and a lower GFR. On the contrary, the histological findings at diagnosis showed no significant difference between failed and unfailed grafts at 24 mo in both groups.

Based of our analysis, we are unable to define any characteristics at diagnosis that influence prognosis. The goal of any study on this topic should be to identify a certain population who would benefit from therapy (in this case Rituximab associated with PE and IVIG). Unfortunately, no study has fulfilled this scope to the best of our knowledge[15,16]. The search for characteristics that label the population that would benefit from these therapies is even more important when we consider the significant risk associated with these therapies. In our study, we noted a significant increase in the bacterial infection rate in the PE-IVIG-RTX group (OR: 4, 1.7-9.3).

Upon comparing our results to the literature data, Bachelet et al[13] also reported no improvements in graft survival or renal functional tests in 21 patients with cAMR-associated severe transplant glomerulopathy who received IVIG and two doses of RTX. Similar outcomes (no differences in eGFR decline, increase of proteinuria, Banff scores at one year, or MFI of the immunodominant DSA) were also shown in a very recent randomized clinical trial evaluating efficacy and safety of IVIG combined with RTX in 25 patients with cAMR[14].

All these data are in contrast with previous evidence from Billing’s paper, showing a GFR improvement or stabilization at 12 mo in four out of six pediatric patients who were IVIG and RTX treated[3]. A subsequent analysis of 20 pediatric patients, published by the same author, reported a lower median GFR loss in the 24 mo follow- up after IVIG and RTX, compared with GFR loss in the 6 mo prior to treatment[23]. When also excluding differences between pediatric and adult KTRs, and the absence of a control group in the two studies by Billing et al[23], it is clear that a minor GFR-worsening might not result from a therapeutic effect, but instead represent the natural history of the disease and its early diagnosis.

In a retrospective analysis, Redfield et al[2] examined 123 patients with severe cAMR; Kaplan–Meier survival showed an association of steroids/IVIG (together or in combination with rituximab and/or Thymoglobulin) with better graft survival. However, the association between the addition of rituximab or Thymoglobulin to steroids/IVIG with better graft survival did not reach statistical significance.

We acknowledge the limitations of our study, which include the low numerosity, the retrospective design, and the absence of protocol biopsies in the control group. Nonetheless, a low number of treated subjects, the absence of a control group, and retrospective analysis can be found in most studies that involve treatment of this clinical condition[2,4,5,13]. Moreover, we also recognize that three patients in both groups were also treated with steroid boluses in low doses. This observation may be considered as a bias in interpretation due to a possible “positive” effect in the control group, however this may also be seen as a negligible aspect since two out of two of these patients lost their graft.

We recognize that protocol biopsies could have enlightened the question as to whether early lesions could be a marker for a better response to treatment. The absence of protocol biopsies in the control group precludes an adequate histological comparison between the populations. We are therefore able to compare the histopathological findings inside the treatment group, but we are unable to evaluate the progression of the chronic lesions in the control group. However, protocol biopsies are not a current practice for some centers, and cAMR is often diagnosed only after appearance of clinical abnormalities that trigger biopsy indication.

Regarding microvascular inflammation lesions, which are considered to be crucial for disease progression[6,24], we found a reduction in g + ptc score after treatment with PE-IVIG-RTX. One could speculate that if the amelioration of these lesions have a significant clinical impact, it could potentially be noted in a longer follow-up.

In conclusion, no guidelines about the therapeutic management of cAMR is currently available. Our data, along with the results of other groups[12-15], suggest the lack of a prompt and marked effect of a therapeutic protocol with PE, IVIG and RTX, despite good histological improvement (reduction in microvascular inflammation) in the majority of treated patients. It is possible that this treatment could have greater efficacy with a longer follow-up, or in a subset of patients not yet identified, as suggested by other authors[15,16]. Further prospective studies, especially involving innovative therapeutic approaches, are required to improve both the management and long-term results of this severe condition.

Chronic-active antibody-mediated rejection (cAMR) due to de novo or pre-formed donor specific antibody (DSA) is now considered the most important cause of allograft losses. Treatment is focused on reducing or eliminating DSA, antagonizing their detrimental effects on the graft with different approaches, without available guidelines.

An antibody-directed treatment combining high-dose immunoglobulin and rituximab showed beneficial effects (reduction in allograft losses and/or stabilization of glomerular filtration rate) in some patients with cAMR, but these results have now been partially questioned. The role of functional and histological parameters (i.e., GFR proteinuria at diagnosis, microvascular inflammation) in predicting response to antibody-targeted therapy is also a matter of debate.

To evaluate the role of a therapeutic regimen with plasma exchange, intravenous immunoglobulins and rituximab in cAMR settings. To identify in which cases these protocols should be adopted (in all patients or only in specific histopathological and functional settings).

Retrospective case-control analysis in 21 kidney transplant recipients with a diagnosis of cAMR, 9 treated with plasmapheresis, intravenous immunoglobulins and rituximab and 12 patients not treated with antibody-targeted therapies. Primary outcomes were kidney survival and functional outcomes 12 and 24 mo after diagnosis. Histological features (according to BANFF 2015 criteria) and donor specific antibodies characteristics (MFI and C1q-fixing ability) were also evaluated.

No difference in graft survival was noted 12 and 24 mo after cAMR diagnosis. Three out of nine patients in the PE-IVIG-RTX group (33.3%) and 4/12 in the control group (33.3%) lost their allograft, at a median time after diagnosis of 14 mo (min 12 - max 18) and 15 mo (min 7 - max 22), respectively. Kidney functional tests (serum creatinine and eGFR) and proteinuria 24 mo after cAMR diagnosis were strictly similar in both groups. Microvascular inflammation (glomerulitis + peritubular capillaritis score) was significantly reduced after PE-IVIG-RTX in seven out of eight patients (87.5%) in the PE-IVIG-RTX group (median score 3 in pre-treatment biopsy vs 1.5 in post-treatment biopsy; P = 0.047), without any impact on kidney survival. Two out of nine patients had a negative post-treatment Luminex test. However, considering the entire cohort, the median MFI of immunodominant DSA (9800 pre-treatment vs 8200 post-treatment; P = NS) and the percentage of C1q-fixing ability (4/9 - 44.4% - pre-treatment vs 3/9 - 33.3% - post-treatment) were unchanged after treatment with PE-IVIG-RTX. No functional or histological parameter at diagnosis was predictive of clinical outcome.

No clinical improvement after therapy with PE-IVIG-RTX, either in graft survival or in renal functional tests (serum creatinine, eGFR, proteinuria) was observed. In addition, the reduction in the MVI score was not supported by an amelioration in kidney outcomes. Considering our results, we are unable to define any functional or histological characteristics at diagnosis that could influence prognosis.

Future prospective studies that involve innovative therapeutic approaches, longer follow-ups and protocol biopsies are required to: (1) Improve the management and long-term results of this severe condition; and (2) identify a certain population who would benefit from therapy.

Manuscript source: Unsolicited manuscript

Specialty type: Transplantation

Country of origin: Italy

Peer-review report classification

Grade A (Excellent): 0

Grade B (Very good): 0

Grade C (Good): C, C

Grade D (Fair): 0

Grade E (Poor): 0

P- Reviewer: Hori T, Kute VB S- Editor: Cui LJ L- Editor: Filipodia E- Editor: Yin SY

| 1. | Li C, Yang CW. The pathogenesis and treatment of chronic allograft nephropathy. Nat Rev Nephrol. 2009;5:513-519. [PubMed] [DOI] [Cited in This Article: ] [Cited by in Crossref: 93] [Cited by in F6Publishing: 100] [Article Influence: 6.7] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 2. | Redfield RR, Ellis TM, Zhong W, Scalea JR, Zens TJ, Mandelbrot D, Muth BL, Panzer S, Samaniego M, Kaufman DB. Current outcomes of chronic active antibody mediated rejection - A large single center retrospective review using the updated BANFF 2013 criteria. Hum Immunol. 2016;77:346-352. [PubMed] [DOI] [Cited in This Article: ] [Cited by in Crossref: 55] [Cited by in F6Publishing: 56] [Article Influence: 7.0] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 3. | Billing H, Rieger S, Ovens J, Süsal C, Melk A, Waldherr R, Opelz G, Tönshoff B. Successful treatment of chronic antibody-mediated rejection with IVIG and rituximab in pediatric renal transplant recipients. Transplantation. 2008;86:1214-1221. [PubMed] [DOI] [Cited in This Article: ] [Cited by in Crossref: 84] [Cited by in F6Publishing: 88] [Article Influence: 5.5] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 4. | Hong YA, Kim HG, Choi SR, Sun IO, Park HS, Chung BH, Choi BS, Park CW, Kim YS, Yang CW. Effectiveness of rituximab and intravenous immunoglobulin therapy in renal transplant recipients with chronic active antibody-mediated rejection. Transplant Proc. 2012;44:182-184. [PubMed] [DOI] [Cited in This Article: ] [Cited by in Crossref: 23] [Cited by in F6Publishing: 24] [Article Influence: 2.0] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 5. | Fehr T, Rüsi B, Fischer A, Hopfer H, Wüthrich RP, Gaspert A. Rituximab and intravenous immunoglobulin treatment of chronic antibody-mediated kidney allograft rejection. Transplantation. 2009;87:1837-1841. [PubMed] [DOI] [Cited in This Article: ] [Cited by in Crossref: 89] [Cited by in F6Publishing: 83] [Article Influence: 5.5] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 6. | Kahwaji J, Najjar R, Kancherla D, Villicana R, Peng A, Jordan S, Vo A, Haas M. Histopathologic features of transplant glomerulopathy associated with response to therapy with intravenous immune globulin and rituximab. Clin Transplant. 2014;28:546-553. [PubMed] [DOI] [Cited in This Article: ] [Cited by in Crossref: 29] [Cited by in F6Publishing: 29] [Article Influence: 2.9] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 7. | Gubensek J, Buturovic-Ponikvar J, Kandus A, Arnol M, Lindic J, Kovac D, Rigler AA, Romozi K, Ponikvar R. Treatment of Antibody-Mediated Rejection After Kidney Transplantation - 10 Years’ Experience With Apheresis at a Single Center. Ther Apher Dial. 2016;20:240–245. [PubMed] [DOI] [Cited in This Article: ] [Cited by in Crossref: 10] [Cited by in F6Publishing: 11] [Article Influence: 1.6] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 8. | Kim MG, Kim YJ, Kwon HY, Park HC, Koo TY, Jeong JC, Jeon HJ, Han M, Ahn C, Yang J. Outcomes of combination therapy for chronic antibody-mediated rejection in renal transplantation. Nephrology (Carlton). 2013;18:820-826. [PubMed] [DOI] [Cited in This Article: ] [Cited by in Crossref: 20] [Cited by in F6Publishing: 21] [Article Influence: 2.1] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 9. | Schwaiger E, Regele H, Wahrmann M, Werzowa J, Haidbauer B, Schmidt A, Böhmig GA. Bortezomib for the treatment of chronic antibody-mediated kidney allograft rejection: a case report. Clin Transpl. 2010;391-396. [PubMed] [Cited in This Article: ] |

| 10. | Kulkarni S, Kirkiles-Smith NC, Deng YH, Formica RN, Moeckel G, Broecker V, Bow L, Tomlin R, Pober JS. Eculizumab Therapy for Chronic Antibody-Mediated Injury in Kidney Transplant Recipients: A Pilot Randomized Controlled Trial. Am J Transplant. 2017;17:682-691. [PubMed] [DOI] [Cited in This Article: ] [Cited by in Crossref: 83] [Cited by in F6Publishing: 85] [Article Influence: 12.1] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 11. | Rostaing L, Guilbeau-Frugier C, Fort M, Mekhlati L, Kamar N. Treatment of symptomatic transplant glomerulopathy with rituximab. Transpl Int. 2009;22:906-913. [PubMed] [DOI] [Cited in This Article: ] [Cited by in Crossref: 22] [Cited by in F6Publishing: 23] [Article Influence: 1.5] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 12. | Touzot M, Couvrat-Desvergnes G, Castagnet S, Cesbron A, Renaudin K, Cantarovich D, Giral M. Differential modulation of donor-specific antibodies after B-cell depleting therapies to cure chronic antibody mediated rejection. Transplantation. 2015;99:63-68. [PubMed] [DOI] [Cited in This Article: ] [Cited by in Crossref: 11] [Cited by in F6Publishing: 11] [Article Influence: 1.2] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 13. | Bachelet T, Nodimar C, Taupin JL, Lepreux S, Moreau K, Morel D, Guidicelli G, Couzi L, Merville P. Intravenous immunoglobulins and rituximab therapy for severe transplant glomerulopathy in chronic antibody-mediated rejection: A pilot study. Clin Transplant. 2015;29:439–446. [PubMed] [DOI] [Cited in This Article: ] [Cited by in Crossref: 26] [Cited by in F6Publishing: 26] [Article Influence: 2.9] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 14. | Moreso F, Crespo M, Ruiz JC, Torres A, Gutierrez-Dalmau A, Osuna A, Perelló M, Pascual J, Torres IB, Redondo-Pachón D. Treatment of chronic antibody mediated rejection with intravenous immunoglobulins and rituximab: A multicenter, prospective, randomized, double-blind clinical trial. Am J Transplant. 2018;18:927-935. [PubMed] [DOI] [Cited in This Article: ] [Cited by in Crossref: 108] [Cited by in F6Publishing: 113] [Article Influence: 18.8] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 15. | Muller YD, Ghaleb N, Rotman S, Vionnet J, Halfon M, Catana E, Golshayan D, Venetz J-P, Aubert V, Pascual M. Rituximab as monotherapy for the treatment of chronic active antibody-mediated rejection after kidney transplantation. Transpl Int. 2018;1–5. [DOI] [Cited in This Article: ] [Cited by in Crossref: 8] [Cited by in F6Publishing: 9] [Article Influence: 1.5] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 16. | Smith RN, Malik F, Goes N, Farris AB, Zorn E, Saidman S, Tolkoff-Rubin N, Puri S, Wong W. Partial therapeutic response to Rituximab for the treatment of chronic alloantibody mediated rejection of kidney allografts. Transpl Immunol. 2012;27:107-113. [PubMed] [DOI] [Cited in This Article: ] [Cited by in Crossref: 31] [Cited by in F6Publishing: 27] [Article Influence: 2.3] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 17. | Loupy A, Haas M, Solez K, Racusen L, Glotz D, Seron D, Nankivell BJ, Colvin RB, Afrouzian M, Akalin E. The Banff 2015 Kidney Meeting Report: Current Challenges in Rejection Classification and Prospects for Adopting Molecular Pathology. Am J Transplant. 2017;17:28-41. [PubMed] [DOI] [Cited in This Article: ] [Cited by in Crossref: 447] [Cited by in F6Publishing: 482] [Article Influence: 68.9] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 18. | Sautenet B, Blancho G, Büchler M, Morelon E, Toupance O, Barrou B, Ducloux D, Chatelet V, Moulin B, Freguin C. One-year Results of the Effects of Rituximab on Acute Antibody-Mediated Rejection in Renal Transplantation: RITUX ERAH, a Multicenter Double-blind Randomized Placebo-controlled Trial. Transplantation. 2016;100:391-399. [PubMed] [DOI] [Cited in This Article: ] [Cited by in Crossref: 122] [Cited by in F6Publishing: 125] [Article Influence: 15.6] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 19. | Messina M, Ariaudo C, Praticò Barbato L, Beltramo S, Mazzucco G, Amoroso A, Ranghino A, Cantaluppi V, Fop F, Segoloni GP. Relationship among C1q-fixing de novo donor specific antibodies, C4d deposition and renal outcome in transplant glomerulopathy. Transpl Immunol. 2015;33:7-12. [PubMed] [DOI] [Cited in This Article: ] [Cited by in Crossref: 19] [Cited by in F6Publishing: 19] [Article Influence: 2.1] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 20. | Immenschuh S, Zilian E, Dämmrich ME, Schwarz A, Gwinner W, Becker JU, Blume CA. Indicators of treatment responsiveness to rituximab and plasmapheresis in antibody-mediated rejection after kidney transplantation. Transplantation. 2015;99:56-62. [PubMed] [DOI] [Cited in This Article: ] [Cited by in Crossref: 20] [Cited by in F6Publishing: 22] [Article Influence: 2.4] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 21. | Loupy A, Lefaucheur C, Vernerey D, Prugger C, Duong van Huyen JP, Mooney N, Suberbielle C, Frémeaux-Bacchi V, Méjean A, Desgrandchamps F. Complement-binding anti-HLA antibodies and kidney-allograft survival. N Engl J Med. 2013;369:1215-1226. [PubMed] [DOI] [Cited in This Article: ] [Cited by in Crossref: 656] [Cited by in F6Publishing: 650] [Article Influence: 59.1] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 22. | Schnaidt M, Weinstock C, Jurisic M, Schmid-Horch B, Ender A, Wernet D. HLA antibody specification using single-antigen beads--a technical solution for the prozone effect. Transplantation. 2011;92:510-515. [PubMed] [DOI] [Cited in This Article: ] [Cited by in Crossref: 182] [Cited by in F6Publishing: 183] [Article Influence: 14.1] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 23. | Billing H, Rieger S, Süsal C, Waldherr R, Opelz G, Wühl E, Tönshoff B. IVIG and rituximab for treatment of chronic antibody-mediated rejection: a prospective study in paediatric renal transplantation with a 2-year follow-up. Transpl Int. 2012;25:1165-1173. [PubMed] [DOI] [Cited in This Article: ] [Cited by in Crossref: 67] [Cited by in F6Publishing: 69] [Article Influence: 5.8] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 24. | Sis B, Jhangri GS, Riopel J, Chang J, de Freitas DG, Hidalgo L, Mengel M, Matas A, Halloran PF. A new diagnostic algorithm for antibody-mediated microcirculation inflammation in kidney transplants. Am J Transplant. 2012;12:1168-1179. [PubMed] [DOI] [Cited in This Article: ] [Cited by in Crossref: 164] [Cited by in F6Publishing: 165] [Article Influence: 13.8] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |