Beluga whales (Delphinapterus leucas) in an aquarium

Beluga whales (Delphinapterus leucas) in an aquarium

This image was taken by Diliff. Click here to view Wikimedia source.

This work is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-ShareAlike 2.5 Generic License.

This work is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-ShareAlike 2.5 Generic License.

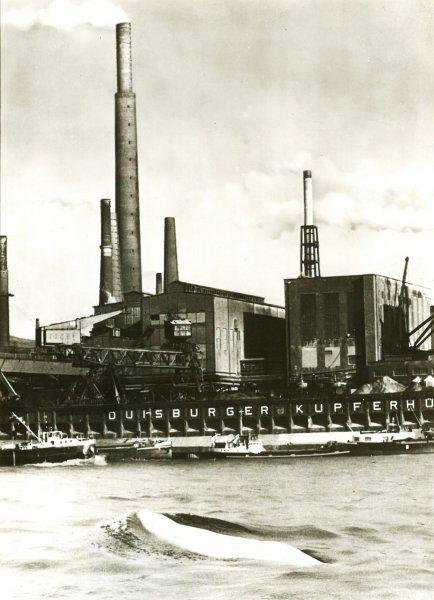

In 1996, the Rhine was declared to be the cleanest river in Europe. It had come a long way. From the 1950s to the 1970s, the Rhine was known as the “sewer of Europe”: the water was unsafe to consume or even swim in, and the ecosystem within came to the brink of collapse by 1975. On 18 May 1966 a white whale, native to Arctic and subarctic waters, was spotted in the Rhine in Duisburg, West Germany—250 kilometers inland. This beluga whale spent the next four weeks swimming up and down the Lower Rhine, at the time an extremely polluted river. The beluga became a media celebrity in Germany and the Netherlands. German media was quick to dub him “Moby Dick,” after the famous sperm whale in Herman Melville’s novel.

There are no beluga whales in the North Sea. This beluga was originally captured in shallow waters off the Canadian east coast, from where it was being transported to a zoo in England. En route it went overboard during a storm. It is rare—but not unprecedented—for whales to accidently swim up European rivers. In their north polar home waters, beluga whales sometimes meet in river deltas for mating.

External video. Link: https://www.youtube.com/embed/JFBGhB-APMs

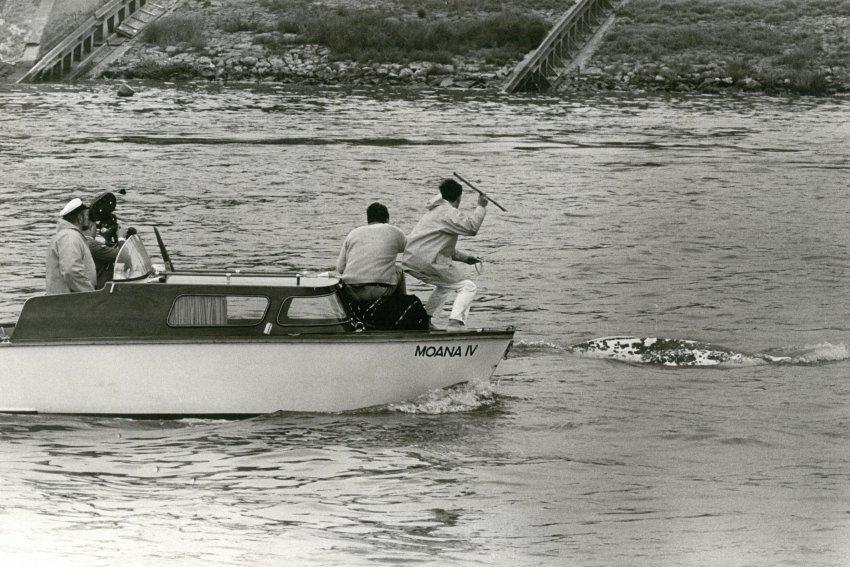

A news report from 1966 uses original footage of the beluga whale. The video shows a zeppelin that was hired by a German newspaper to take pictures of the whale and to feed him. It also includes footage of the nets, tranquilizers, and even the bow and arrow that were used in the attempt to capture the whale. The video briefly argues that the beluga has no chance of survival in the polluted river, so it should be captured instead.

As this matter was quite unusual, the water police alerted the recently appointed director of the Duisburg zoo, Wolfgang Gewalt, a zoologist—who tried to capture Moby Dick for his zoo’s dolphinarium. At that time, no German zoo had any belugas. The hunt was performed with the simplest of tools, such as stitched-together tennis nets. But the beluga always managed to outswim its hunters. When Gewalt tried unsuccessfully to shoot the whale with tranquilizers and it then disappeared for many days, the atmosphere changed and the population called out for his arrest. Readers sent worried letters to newspapers, discussing what the whale would eat in a freshwater river, outside its natural habitat, and if it needed more energy as it had no salt water to stay buoyant.

On 13 June the whale even managed to attract the attention of politicians in Bonn, the West German capital. Moby Dick resurfaced during a NATO press conference: a messenger informed the plenum, and politicians and journalists from many different countries ran out, trying to catch a glimpse of the beluga. After four weeks Moby Dick’s odyssey came to an end: on 16 June the beluga made it back to the North Sea on its own. It was last seen at Hoek van Holland.

The hunt for the whale begins. Dark spots are apparent on the beluga, which it developed after spending four weeks in the polluted water of the Rhine

The hunt for the whale begins. Dark spots are apparent on the beluga, which it developed after spending four weeks in the polluted water of the Rhine

The name of the photographer is unknown. This image was used by the Duisburger Bürger Illustrierte and can be found in the Stadtarchiv Duisburg.

This work is used by permission of the copyright holder.

The beluga developed dark patches on his skin from being in the river, which newspapers and their readers attributed to the level of water pollution. Duisburg, the world’s largest inland harbor, is in the heavily industrialized Ruhr region that developed during the Industrial Revolution, due to its plentiful coal and close proximity to waterways. After World War II, the Ruhr region’s coal mining and steel production had helped West Germany accomplish the Wirtschaftswunder (“economic miracle”). Conservationists who raised concerns about pollution in the Rhine found it hard to present a rebuttal to industry’s arguments of “prosperity for all.” Environmental concerns fell by the wayside and the River Rhine was polluted by chemical and industrial waste, as well as sewage water that was routinely discharged into the river. During this period, the fear of smog and air pollution had been much more present in public debate than water pollution. It would take time to realize that river pollution was also a serious threat to public health, and it was only when it became apparent that the river’s polluted state impacted the economy as well as tourism that laws were passed in the German parliament regulating discharges into rivers. The Federal Water Act came into effect in 1957 and was updated in 1970.

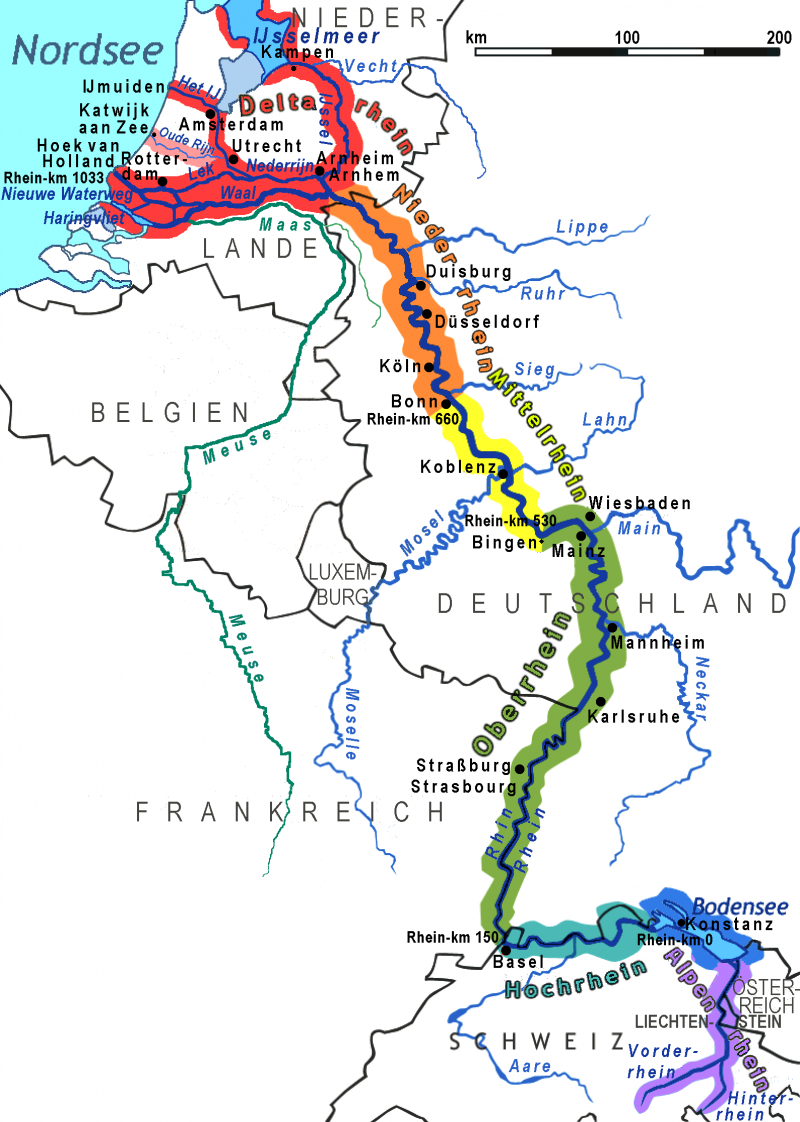

Map of the Rhine, showing the course of the river from the Alps through Germany and France to the river delta in the Netherlands. The Lower Rhine (Niederrhein), here highlighted in orange, is relevant for this story

Map of the Rhine, showing the course of the river from the Alps through Germany and France to the river delta in the Netherlands. The Lower Rhine (Niederrhein), here highlighted in orange, is relevant for this story

This map was created by Ulamm. Click here to view Wikimedia source.

This work is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-ShareAlike 3.0 Unported License.

This work is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-ShareAlike 3.0 Unported License.

The Rhine flows through several countries, all of which had formed the International Commission for the Protection of the Rhine in 1950. By 1966, not much had happened in the way of preventing the Rhine’s water becoming more polluted. Moby Dick—who became a darling of the public—temporarily raised awareness of river pollution, but it was not a watershed event for the recovery of the Rhine. The fact that even an event this spectacular could not inspire the cleanup of the Rhine shows that concerns about human uses of the river (fishing, transportation, tourism) and human health seemed to outweigh concern for animals like Moby Dick. Environmentalism took a different turn in the 1970s: it was no longer just about Naturschutz, the protection of nature, i.e., animals such as birds; the understanding of the interconnectedness of different parts of the environment created the urge for a more complex Umweltschutz, the protection of the environment, that took into consideration issues like pollution. It wasn’t until the late 1980s that efforts to help the Rhine recover really accelerated: in 1986 the agrochemical storehouse Sandoz in Switzerland caught fire and released large amounts of toxic chemicals into the Rhine; downstream this caused the death of many fish. Subsequently, appropriate efforts were made and 10 years later, the Rhine had managed to recover. Today, significantly less pollutants and heavy metals are being discharged into the river; there are habitat restoration projects, notably for salmon, as well as efforts to reestablish parts of the river’s floodplain. This proves that the effects of water pollution on riverine populations can at least partially be reversed.

How to cite

Kleemann, Katrin. “‘Moby Dick’ in the Rhine: How a Beluga Whale Raised Awareness of Water Pollution in West Germany.” Environment & Society Portal, Arcadia (Spring 2018), no. 6. Rachel Carson Center for Environment and Society. doi.org/10.5282/rcc/8222.

ISSN 2199-3408

Environment & Society Portal, Arcadia

This work is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License.

This work is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License.

2018 Katrin Kleemann

This refers only to the text and does not include any image rights.

Please click on an image to view its individual rights status.

- Blackbourn, David. The Conquest of Nature: Water, Landscape, and the Making of Modern Germany. New York: W. W. Norton, 2006.

- Cioc, Mark. The Rhine: An Eco-Biography 1815–2000. Weyerhaeuser Environmental Books. Seattle: University of Washington Press, 2002.

- Dominick, Raymond H. The Environmental Movement in Germany: Prophets and Pioneers, 1871–1971. Bloomington: Indiana University Press, 1992.

- Gewalt, Wolfgang. Auf den Spuren der Wale: Expeditionen von Alaska bis Kap Hoorn. Düsseldorf: Econ-Verlag, 1986.

- Mauch, Christof and Thomas Zeller. Rivers in History: Perspectives on Waterways in Europe and North America. Pittsburgh: University of Pittsburgh Press, 2008.

- Uekötter, Frank. Am Ende der Gewissheiten. Die ökologische Frage im 21. Jahrhundert. Frankfurt: Campus Verlag, 2011.

- Zelko, Frank. Make it a Green Peace! The Rise of Countercultural Environmentalism. New York: Oxford University Press, 2013.