Acenocoumarol Induced Spinal Epidural Hematoma: A Rare Case Report

Batoul Awada1, Kassem Haidar1, Dani Hamzeh1, Walaa Shreif2, Malek Moussa3 and Rima Chaddad4,*

1Cardiology department, Beirut Cardiac Institute, Lebanon

2Pulmonary critical care department, Lebanon

3Cardiology department, Head of Cardiac critical care unit, BCI, Lebanon

4Cardiology department, Colmar, France

Received Date: 04/05/2024; Published Date: 18/09/2024

*Corresponding author: Rima Chaddad, Cardiology department, Colmar, France

Abstract

Spinal epidural hematoma (SEH) is a rare diagnosis, with trauma being the most common cause. SEH caused by coagulopathy is even rarer.

The incidence of Spontaneous SEH defined by a bleeding within the epidural space of the spine without a traumatic injury or iatrogenic cause is estimated at 0.1 in 100,000 per year.

The late diagnosis or even worse the misdiagnosis of this condition can result in spinal cord compression, paraplegia, and mortality.

Magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) is the gold standard modality for diagnosis, and the best treatment for epidural hematoma is urgent decompression of the spine.

We present a 62-year-old female patient who was on long-term warfarin treatment for atrial fibrillation. She developed sudden onset interscapular pain that

progressed rapidly in one day to weakness in both lower limbs and ended up with respiratory failure. She underwent an MRI that documented Epidural hematoma.

Introduction

Spinal epidural hematoma is a rare condition [1]. The patients usually presented with sudden back pain that may worsen from simple partial motor deficit in the extremities to a complete neurological disability [2]. MRI is the method of choice to diagnose this condition and urgent surgical decompression of the spinal canal is mandatory regardless of the clinical setting [1].

Case Presentation

A 62-year-old female patient with a significant past medical history of lymphoma, thyroidectomy, chronic atrial fibrillation on warfarin, presented for sudden onset of bilateral lower limb weakness.

3 days prior to presentation to the hospital, she felt interscapular pain radiating to both shoulders and neck, followed, 1 day later, by paresthesia and weakness in both legs in ascending pattern.

Upon arrival, she was conscious and fully oriented with a loss of sensation and motor power of 0/5 in both lower extremities. Her vital signs were within normal limits except for a high-grade fever of 40-degree C.

The International normalized ratio (INR) was therapeutic: 2.56 with normal metabolic workup without evidence of elevated inflammatory markers.

Differential diagnosis at this stage included Guillain-Barre syndrome, acute transverse myelitis, spinal cord compression, and acute aortic dissection.

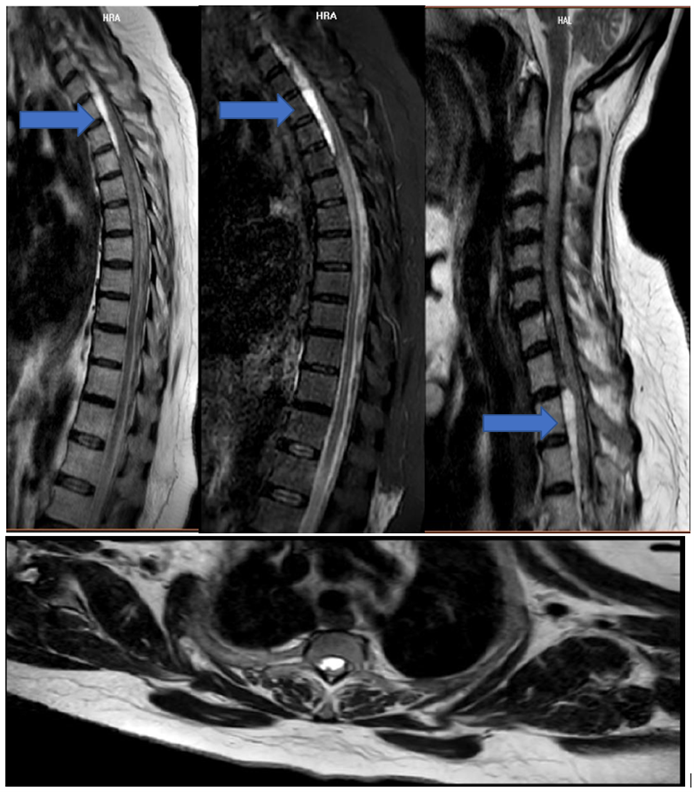

MRI of the brain and dorso-lumbar spine showed anterior epidural space hematoma with severe cervical-dorsal myelopathy (Figure 1).

Sudden Cardiac arrest occurred with regain of spontaneous circulation after 15 minutes of cardiopulmonary resuscitation. She was intubated and transferred urgently to the operating room where the dura matter was found edematous and bloody, laminectomy of the C6-7-D1-D2-D3 was done with evacuation of the large epidural hematoma.

No neurologic improvement was noted after surgery, and her clinical status was deteriorating, until she died after few days.

Figure 1: Large mass lesion with abnormal high signal intensity on T1W and T2W, maximal AP diameter of (8mm) seen in the anterior epidural space from C7 vertebral body till D4 (blue arrow) causing significant spinal cord compression more significant at the D2 vertebral body level accompanied with diffuse spinal cord.

Discussion

Spinal epidural hematoma is unusual with annual incidence of 1/100,000 persons [3].

The greater use of MRI in making radiological diagnosis is probably what has caused the rise in reported SEHs [4].

A significant risk factor for SEH is the use of anticoagulants, such as warfarin, in 25-70% of patients [5].

INR, which depends on patient compliance to treatment, active medical issues, comorbidities, and interaction with the other drugs, should be requested regularly to check the anticoagulant effect of VKA in order to prevent the occurrence of such condition [6].

Despite this, no absolute "safe" INR should be approved as in multiple documented cases of SEH, coagulation variables are within the therapeutic range [7].

Patients using anticoagulants or receiving antiplatelet therapy or those with endogenous coagulopathies may experience a delay in clot formation that permits the liquid hematoma to spread [7].

It is thought that a spreading hematoma could loosen the filaments in the dura that cross the epidural space, allowing the hematoma to spread and decompress the dural sac as a result [4].

The clot-delaying mechanisms, however, might also induce further bleeding, which enlarges the size of hematoma.[4] It is a significant hemorrhagic diathesis that affects the survival of the patient [8].

The clinical symptoms may differ depending on the location and size of the hematoma. However, the most frequent and usual clinical symptom is a sudden, intense pain that may or may not radiate at the damaged spinal cord segment, followed by manifestations of spinal cord compression [9].

These signs and symptoms typically appear three hours after the onset of pain, and some patients may even experience them two to three days later [10].

The cervicothoracic and thoracolumbar junctions are the two areas of the spinal cord most prone to SEHs. This preference has been attributed to a rumored weakening of the epidural venous plexus in these regions [11].

Acute spinal epidural hematomas have a severe course that can occasionally result in spinal shock or even death if the hemorrhage occurs at a high cervical level [12].

Spinal hematomas are surgical emergencies, and earlier treatment usually results in better results. Although acute presentation can mimic cerebrovascular events, it poses a significant diagnostic challenge [13].

Once it is diagnosed, urgent surgical laminectomy and hematoma evacuation should be done with a tailored dural opening if MRI is unable to pinpoint the exact bleeding site [8].

With a maximum interval of 48 hours, Groen et al. discovered a strong relationship between surgical delay and neurological sequelae [14].

The size and location of the hematoma, the significance of preoperative neurological deficit, the interval from clinical manifestation to surgical decompression, and the interval from clinical presentation to maximal deficit are the key prognostic factors [15].

Conclusion

Spinal epidural hematoma that occurs spontaneously is a rare and serious medical emergency.

Our case report emphasizes the importance of high index of suspicion of SEH in patients under warfarin who complain of any kind of spinal pain mainly if associated with limb weakness.

Furthermore, an MRI imaging must be performed urgently and once the diagnosis is made, intervention must be undergone on spot.

References

- Al-Mutair A, Bednar Spinal epidural hematoma. J Am Acad Orthop Surg, 2010; 18(8): 494-502. doi: 10.5435/00124635-201008000-00006.

- Babayev R, Ekşi MŞ. Spontaneous thoracic epidural hematoma: a case report and literature Childs Nerv Syst, 2016; 32: 181–187.

- Baek BS, Hur JW, Kwon KY, Lee Spontaneous spinal epidural hematoma. J Korean Neurosurg Soc, 2008; 44: 40–42.

- Sandvig A, Jonsson H. Spontaneous chronic epidural hematoma in the lumbar spine associated with Warfarin intake: a case Springerplus, 2016; 5(1): 1832. doi: 10.1186/s40064-016-3546-x.

- KirazliY, AkkocY, Kanyilmaz S. Spinal epidural hematoma associated with oral anticoagulation Am J Phys Med Rehabil, 2004; 83: 220e223.

- Rudasill SE, Liu J, Kamath AF. Revisiting the International Normalized Ratio (INR) Threshold for Complications in Primary Total Knee Arthroplasty: An Analysis of 21,239 Cases. J Bone Joint Surg Am, 2019; 101(6): 514-522. doi: 2106/JBJS.18.00771.

- Goyal G, Singh R, Raj Anticoagulant induced spontaneous spinal epidural hematoma, conservative management or surgical intervention-A dilemma? Journal of Acute Medicine, 2016; 6: 38-42. DOI: 10.1016/j.jacme.2016.03.006.

- El-Azrak M, Noumairi M, Oulalite MA, El Mir S, Kachmar S, Bkiyar H, et al. Spontaneous spinal epidural hematoma in a patient on acenocoumarol for valvular atrial fibrillation: A rare case report. Ann Med Surg (Lond), 2021; 72: 103076. doi: 1016/j.amsu.2021.103076.

- Raouf A, Goyal S, Van Horne N, et Spontaneous spinal epidural hematoma secondary to rivaroxaban use in a patient with paroxysmal atrial fibrillation. Cureus, 2020; 12: e10417.

- Li X, Zeng Z, Yang Y, Ding W, Wang L, Xu Y, et al. Warfarin-related epidural hematoma: a case report. J Int Med Res, 2022; 50(3): 3000605221082891. doi: 10.1177/03000605221082891.

- Adamson DC, Bulsara K, Bronce PR. Spontaneous cervical epidural hematoma: case report and literature Surg Neurol, 2004; 62: 156–159.

- Chan DT, Boet R, Poon WS, Yap F, Chan YL. Spinal shock in spontaneous cervical spinal epidural haematoma, Acta Wien, 2004; 46: 161–162.

- El Alayli A, Neelakandan L, Krayem Spontaneous Spinal Epidural Hematoma in a Patient on Apixaban for Nonvalvular Atrial Fibrillation. Case Rep Hematol, 2020; 2020: 7419050. doi: 10.1155/2020/7419050.

- Groen RJM, Van Alphen HAM. Operative treatment of spontaneous spinal epidural hematomas, a study of the factors determining postoperative outcome, Neurosurgery, 1996; 39: 494–508.