Published online May 15, 2024. doi: 10.4251/wjgo.v16.i5.1745

Peer-review started: November 15, 2023

First decision: January 30, 2024

Revised: February 20, 2024

Accepted: March 18, 2024

Article in press: March 18, 2024

Published online: May 15, 2024

Colorectal neuroendocrine neoplasms (NENs) are a rare malignancy that primarily arises from the diffuse distribution of neuroendocrine cells in the colon and rectum. Previous studies have pointed out that the status of lymph node may be used to predict the prognosis.

To investigate the predictive values of lymph node ratio (LNR), positive lymph node (PLN), and log odds of PLNs (LODDS) staging systems on the prognosis of colorectal NENs treated surgically, and compare their predictive values.

This cohort study included 895 patients with colorectal NENs treated surgically from the Surveillance, Epidemiology, and End Results database. The endpoint was mortality of patients with colorectal NENs treated surgically. X-tile software was utilized to identify most suitable thresholds for categorizing the LNR, PLN, and LODDS. Participants were selected in a random manner to form training and testing sets. The prognosis of surgically treating colorectal NENs was examined using multivariate cox analysis to assess the associations of LNR, PLN, and LODDS with the prognosis of colorectal NENs. C-index was used for assessing the predictive effectiveness. We conducted a subgroup analysis to explore the different lymph node staging systems’ predictive values.

After adjusting all confounding factors, PLN, LNR and LODDS staging systems were linked with mortality in patients with colorectal NENs treated surgically (P < 0.05). We found that LODDS staging had a higher prognostic value for patients with colorectal NENs treated surgically than PLN and LNR staging systems. Similar results were obtained in the different G staging subgroup analyses. Furthermore, the area under the receiver operating characteristic curve values for LODDS staging system remained consistently higher than those of PLN or LNR, even at the 1-, 2-, 3-, 4-, 5- and 6-year follow-up periods.

LNR, PLN, and LODDS were found to significantly predict the prognosis of patients with colorectal NENs treated surgically.

Core Tip: The present study utilized data extracted from a publicly available Surveillance, Epidemiology, and End Results database and employed multivariate cox analysis, revealing that lymph node ratio (LNR), positive lymph node (PLN), and log odds of PLNs (LODDS) staging systems was significantly related to mortality among patients with colorectal neuroendocrine neoplasms treated surgically. Additionally, the LODDS staging demonstrated a higher prognostic value compared to the PLN and LNR staging systems.

- Citation: Zhang YY, Cai YW, Zhang X. Different lymph node staging systems for predicting the prognosis of colorectal neuroendocrine neoplasms. World J Gastrointest Oncol 2024; 16(5): 1745-1755

- URL: https://www.wjgnet.com/1948-5204/full/v16/i5/1745.htm

- DOI: https://dx.doi.org/10.4251/wjgo.v16.i5.1745

Colorectal neuroendocrine neoplasms (NENs) are a rare malignancy that primarily arises from the diffuse distribution of neuroendocrine cells in the colon and rectum[1]. Recently, its prevalence has increased due to the widespread adoption of colonoscopy and the introduction of colorectal cancer screening measures[2]. Typically, colorectal NENs exhibit a poor prognosis when lymph node metastasis occurs, which greatly reduces the survival rates of patients[3].

Previous studies have pointed out that the status of lymph node may be used to predict the prognosis[3,4]. According to the World Health Organization classification, colorectal NENs was subdivided into well-differentiated colorectal neuroendocrine tumors [colorectal NETs; grade (G)1 and G2], and poorly differentiated colorectal neuroendocrine carcinomas (colorectal NECs; G3)[5]. However, when it comes to colorectal NETs and colorectal NECs, lymph node (N) staging protocols were adopted by the American Joint Committee on Cancer (AJCC): The staging system for colorectal NETs was relied on the identification of positive lymph nodes (PLNs), whereas for colorectal NECs it was determined by the quantity of PLNs[6]. The lymph node ratio (LNR) indicating PLNs to the total number of lymph nodes examined, serves as a significant prognostic factor for patients with colorectal cancer[7]. In the study of Zhang et al[8], a higher LNR was found to be significantly associated with a shorter overall survival of colorectal cancer patients. The log odds of PLNs (LODDS), reported as a novel prognostic factor for colonic cancers, exhibited higher predictive accuracy in comparison to LNR stages[9,10]. LODDS is calculated by the following formula: Log [(PLNs + 0.5)/(negative lymph nodes + 0.5)]. A study was conducted by Gao et al[11] utilizing retrospective data to compare the predictive accuracy of LNR, PLN, and LODDS staging systems in forecasting cause-specific survival rates among pancreatic NENs, and their findings revealed that PLN staging system outperformed both LNR and LODDS staging methods. However, to our knowledge, there are few studies to explore the predictive significance of LNR and LODDS staging systems for colorectal NENs.

Thus, we intended to investigate the predictive values of various lymph node staging systems on the prognosis of colorectal NENs treated surgically, and compare their predictive values, which might provide a reference for the improvement of lymph node staging of colorectal NENs.

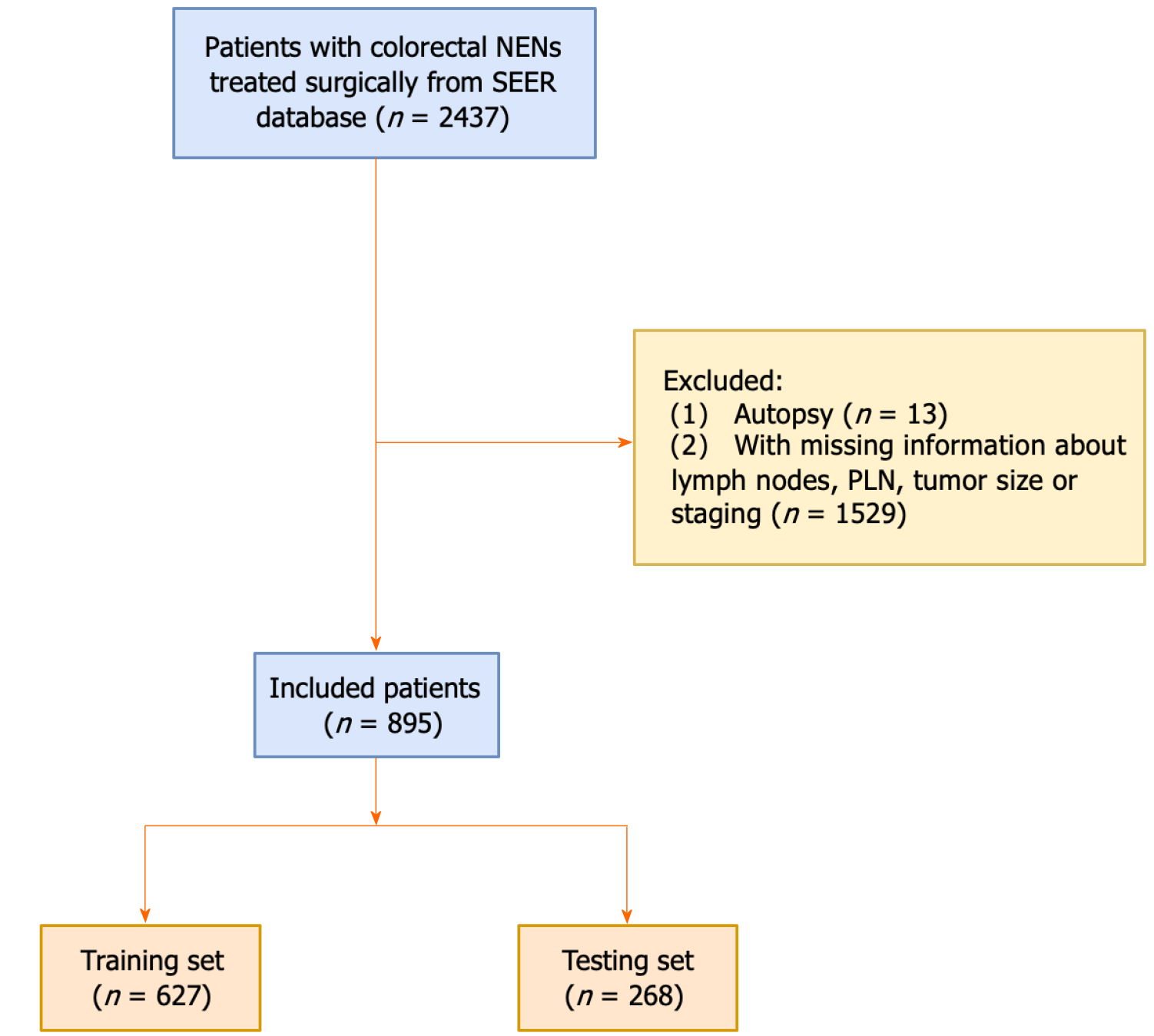

This cohort study was performed based on the Surveillance, Epidemiology, and End Results (SEER) database, collecting some data of cancer patients, such as tumor data, demographic data, causes of death, and survival time from 18 regions across the United States[12]. We identified primary colorectal NENs patients by using third revision of the International Classification of Diseases for Oncology codes (ICD-O-3) from the SEER database 1992-2018. Inclusion criteria: (1) Patients were diagnosed as primary colorectal NENs; (2) lymph node testing was performed; and (3) patients received a surgical procedure. Excluded criteria: (1) The source of diagnosis is autopsy, death certificate or only clinical diagnosis alone; (2) patients with incomplete clinicopathological characteristics; and (3) tumor size = 0. Finally, 895 patients with colorectal NENs were included in this study (Figure 1). Given that the data utilized in this study was obtained from the SEER database which is a publicly accessible and de-identified database, and does not involve any interaction of human subjects or personally identifiable information, the requirement of ethical approval for this study was waived by the Institutional Review Board of Zhaoqing Medical College. All individuals provided written informed consent before participating in the SEER database.

We retrieved some variables in this study, including age, gender, race, marital status, G staging, tumor (T) staging, N staging, metastasis (M) staging, tumor size, primary tumor site, perineural invasion, the number of PLN, the number of total lymph nodes, LNR, LODDS, carcinoembryonic antigen (CEA), radiation, chemotherapy, and vital status. The primary tumor site was defined as left-sided, right-sided and rectum. The classification of T staging includes T1 (involving the mucosa or submucosa), T2 (affecting the muscularis propria or subserosa), T3 (penetrating the serosa), T4 (extending to adjacent structures), and TX (unknown); the classification of N staging includes three categories: N0 (absence of PLNs), N1 (1-9 positive nodes), and N2 (≥ 10 positive nodes); and M staging includes categories of M0 and M1, M0 indicates the absence of distant metastasis, and M1 indicates the presence of distant metastasis[13]. We employed X-tile software to identify the most suitable thresholds for categorizing the PLN, LNR, and LODDS staging systems. Subsequently, we divided LNR, PLN, and LODDS into three distinct groups. PLN staging system included PLN1 (< 5), PLN2 (5-9), and PLN3 (≥ 10); LNR staging system included LNR1 (less than 0.30), LNR2 (between 0.30 and 0.65), and LNR3 (equal to or greater than 0.65); LODDS staging system included LODDS1 (< 0.47), LODDS2 (0.47-1.59), and LODDS3 (≥ 1.59).

The main outcome was considered as death of patients with colorectal NENs. The median follow-up time was 42.00 (9.00, 73.00) months.

The continuous variables with normal distribution were presented as mean ± SD, and the comparison between groups was carried out by the student’s t-test; and the continuous variables with skewed distribution were presented as the median and quartiles M (Q1, Q3), and the comparison between groups was carried out using rank sum test. The categorical variables adopted the number of cases and composition ratio n (%) to describe, and the difference of groups were compared by chi-square test. All analyses were conducted using X-tile and SAS 9.4 (SAS Institute Inc., Cary, NC, United States) software.

All included patients were randomly selected as the training set for the construction of prediction models and testing set for validating the models at the ratio of 7:3. Then, in the training set, we used univariate cox analysis to screen out the possible confounding factors. Multivariate cox analyses were adopted to investigate the associations of PLN, LNR, and LODDS staging systems with the prognosis of colorectal NENs treated surgically. Three models were built in this study: Model 1 was coarse model; model 2 adjusted for gender and age; model 3 adjusted for gender, age, marital status, primary tumor site, G stage, T stage, M stage, tumor size, perineural invasion, CEA, and chemotherapy. Harrell’s concordance index (C-index) was used to assess the predictive efficacy of different lymph node staging systems (PLN, LNR, and LODDS) on the prognosis of colorectal NENs. Additionally, the time-dependent area under the receiver operating characteristic curve (AUC) analysis was performed in both the training and testing sets to examine the predictive ability of PLN, LNR, and LODDS staging systems over a 6-year period. We also conducted a subgroup analysis based on the G staging to compare the predictive value of different lymph node staging systems. Hazard ratio (HR) with 95% confidence interval (95%CI) was calculated. P < 0.05 was considered as significant in this study.

Totally, 895 patients with colorectal NENs were enrolled into this study. The training set comprised 627 patients, while the testing set consisted of 268 patients. Table 1 presents the characteristics of all patients, along with a balance examination conducted between the training and testing sets. Among 895 patients with colorectal NENs, the mean age was 63.79 years ± 13.05 years, including 424 (47.37%) men and 471 (52.63%) women. 69.16% patients with colorectal NENs had a tumor size of less than 5 cm. The median number of PLN, the number of total lymph nodes, LNR, and LODDS were 3.00, 15.00, 0.21, and 0.30, respectively. The mortality rate was 54.86% in the present study. Additionally, the equilibrium test for both the training and testing sets revealed no statistical difference between groups (P > 0.05).

| Variables | Total, n = 895 | Training set, n = 627 | Testing set, n = 268 | Statistics | P value |

| Gender | χ2 = 0.197 | 0.657 | |||

| Female | 471 (52.63) | 333 (53.11) | 138 (51.49) | ||

| Male | 424 (47.37) | 294 (46.89) | 130 (48.51) | ||

| Age, yr, mean ± SD | 63.79 ± 13.05 | 63.62 ± 12.89 | 64.18 ± 13.44 | t = 0.58 | 0.560 |

| Race | χ2 = 4.244 | 0.120 | |||

| Black | 140 (15.64) | 93 (14.83) | 47 (17.54) | ||

| White | 670 (74.86) | 481 (76.71) | 189 (70.52) | ||

| Others1 | 85 (9.50) | 53 (8.45) | 32 (11.94) | ||

| Marital status | χ2 = 6.700 | 0.082 | |||

| Divorce | 93 (10.39) | 74 (11.80) | 19 (7.09) | ||

| Married | 484 (54.08) | 326 (51.99) | 158 (58.96) | ||

| Single | 152 (16.98) | 105 (16.75) | 47 (17.54) | ||

| Others2 | 166 (18.55) | 122 (19.46) | 44 (16.42) | ||

| Primary tumor site | χ2 = 0.478 | 0.924 | |||

| Left | 623 (69.61) | 437 (69.70) | 186 (69.40) | ||

| Rectum | 154 (17.21) | 109 (17.38) | 45 (16.79) | ||

| Right | 99 (11.06) | 69 (11.00) | 30 (11.19) | ||

| Overlapping lesion of colon/colon/unknown | 19 (2.12) | 12 (1.91) | 7 (2.61) | ||

| G staging | χ2 = 1.664 | 0.797 | |||

| I | 268 (29.94) | 185 (29.51) | 83 (30.97) | ||

| II | 124 (13.85) | 90 (14.35) | 34 (12.69) | ||

| III | 279 (31.17) | 190 (30.30) | 89 (33.21) | ||

| IV | 119 (13.30) | 85 (13.56) | 34 (12.69) | ||

| Unknown | 105 (11.73) | 77 (12.28) | 28 (10.45) | ||

| T staging | - | 0.155 | |||

| T1 | 112 (12.51) | 82 (13.08) | 30 (11.19) | ||

| T2 | 85 (9.50) | 67 (10.69) | 18 (6.72) | ||

| T3 | 471 (52.63) | 321 (51.20) | 150 (55.97) | ||

| T4 | 224 (25.03) | 156 (24.88) | 68 (25.37) | ||

| TX | 3 (0.34) | 1 (0.16) | 2 (0.75) | ||

| N staging | χ2 = 0.107 | 0.948 | |||

| N0 | 223 (24.92) | 158 (25.20) | 65 (24.25) | ||

| N1 | 479 (53.52) | 335 (53.43) | 144 (53.73) | ||

| N2 | 193 (21.56) | 134 (21.37) | 59 (22.01) | ||

| M staging | χ2 = 0.147 | 0.701 | |||

| M0 | 613 (68.49) | 427 (68.10) | 186 (69.40) | ||

| M1 | 282 (31.51) | 200 (31.90) | 82 (30.60) | ||

| Tumor size | χ2 = 0.796 | 0.372 | |||

| < 5 cm | 619 (69.16) | 428 (68.26) | 191 (71.27) | ||

| ≥ 5 cm | 276 (30.84) | 199 (31.74) | 77 (28.73) | ||

| Perineural invasion | χ2 = 0.986 | 0.611 | |||

| No | 57 (6.37) | 41 (6.54) | 16 (5.97) | ||

| Yes | 29 (3.24) | 18 (2.87) | 11 (4.10) | ||

| Unknown | 809 (90.39) | 568 (90.59) | 241 (89.93) | ||

| Number of PLN, M (Q1, Q3) | 3.00 (0.00, 7.00) | 3.00 (0.00, 7.00) | 3.00 (1.00, 7.00) | Z = -0.443 | 0.658 |

| Number of total lymph nodes, M (Q1, Q3) | 15.00 (11.00, 22.00) | 15.00 (11.00, 21.00) | 16.00 (11.00, 22.50) | Z = 0.395 | 0.693 |

| LNR, M (Q1, Q3) | 0.21 (0.00, 0.50) | 0.21 (0.00, 0.50) | 0.21 (0.03, 0.50) | Z = -0.312 | 0.755 |

| LODDS, M (Q1, Q3) | 0.30 (0.07, 1.00) | 0.31 (0.08, 1.00) | 0.30 (0.07, 1.00) | Z = -0.492 | 0.623 |

| CEA | χ2 = 3.341 | 0.188 | |||

| Negative | 37 (4.13) | 21 (3.35) | 16 (5.97) | ||

| Positive | 19 (2.12) | 14 (2.23) | 5 (1.87) | ||

| Unknown | 839 (93.74) | 592 (94.42) | 247 (92.16) | ||

| Chemotherapy | χ2 = 0.000 | 0.992 | |||

| No/unknown | 651 (72.74) | 456 (72.73) | 195 (72.76) | ||

| Yes | 244 (27.26) | 171 (27.27) | 73 (27.24) | ||

| Radiation | χ2 = 0.077 | 0.781 | |||

| No/unknown | 851 (95.08) | 597 (95.22) | 254 (94.78) | ||

| Yes | 44 (4.92) | 30 (4.78) | 14 (5.22) | ||

| Follow-up time, M (Q1, Q3) | 42.00 (9.00, 73.00) | 42.00 (9.00, 73.00) | 42.00 (7.50, 75.50) | Z = -0.000 | 1.000 |

| Vital status | χ2 = 0.197 | 0.657 | |||

| Survival | 404 (45.14) | 280 (44.66) | 124 (46.27) | ||

| Dead | 491 (54.86) | 347 (55.34) | 144 (53.73) |

We adopted a univariate cox analysis in the training set to screen out the possible confounding factors. As shown in the Supplementary Table 1, gender, age, marital status, primary tumor site, G staging, T staging, M staging, tumor size, perineural invasion, CEA, and chemotherapy might be confounding factors affecting the prognosis of colorectal NENs (P < 0.05). Subsequently, multivariate cox analyses were employed to explore the associations of PLN, LNR, and LODDS with the prognosis of colorectal NENs treated surgically (Table 2). The results of the Model 1 showed that the PLN (Tile 3: HR = 3.67, 95%CI: 2.85-4.73), LNR (Tile 2: HR = 1.43, 95%CI: 1.10-1.87; Tile 3: HR = 4.49, 95%CI: 3.48-5.81) and LODDS (Tile 2: HR = 1.34, 95%CI: 1.02-1.76; Tile 3: HR = 4.42, 95%CI: 3.44-5.68) staging systems had a significant prognostic value for colorectal NENs patients treated surgically. After adjusting for all confounding factors, similar results were obtained (Model 3). PLN (Tile 3: HR = 2.05, 95%CI: 1.54-2.74), LNR (Tile 2: HR = 1.54, 95%CI: 1.15-2.07; Tile 3: HR = 2.98, 95%CI: 2.21-4.01) and LODDS (Tile 2: HR = 1.47, 95%CI: 1.09-1.99; Tile 3: HR = 3.03, 95%CI: 2.26-4.05) staging systems were associated with the death risk for patients with colorectal NENs treated surgically.

| Variables | Model 11 | P value | Model 22 | P value | Model 33 | P value |

| HR (95%CI) | HR (95%CI) | HR (95%CI) | ||||

| PLN staging | ||||||

| Tile 1 (< 5) | Ref | Ref | Ref | |||

| Tile 2 (5-10) | 1.10 (0.83-1.45) | 0.526 | 1.28 (0.96-1.70) | 0.090 | 1.14 (0.84-1.56) | 0.400 |

| Tile 3 (≥ 10) | 3.67 (2.85-4.73) | < 0.001 | 3.56 (2.76-4.59) | < 0.001 | 2.05 (1.54-2.74) | < 0.001 |

| LNR staging | ||||||

| Tile 1 (< 0.30) | Ref | Ref | Ref | |||

| Tile 2 (0.30-0.65) | 1.43 (1.10-1.87) | 0.008 | 1.67 (1.28-2.19) | < 0.001 | 1.54 (1.15-2.07) | 0.004 |

| Tile 3 (≥ 0.65) | 4.49 (3.48-5.81) | < 0.001 | 4.48 (3.46-5.79) | < 0.001 | 2.98 (2.21-4.01) | < 0.001 |

| LODDS staging | ||||||

| Tile 1 (< 0.47) | Ref | Ref | Ref | |||

| Tile 2 (0.47-1.59) | 1.34 (1.02-1.76) | 0.039 | 1.56 (1.18-2.06) | 0.002 | 1.47 (1.09-1.99) | 0.013 |

| Tile 3 (≥ 1.59) | 4.42 (3.44-5.68) | < 0.001 | 4.36 (3.38-5.61) | < 0.001 | 3.03 (2.26-4.05) | < 0.001 |

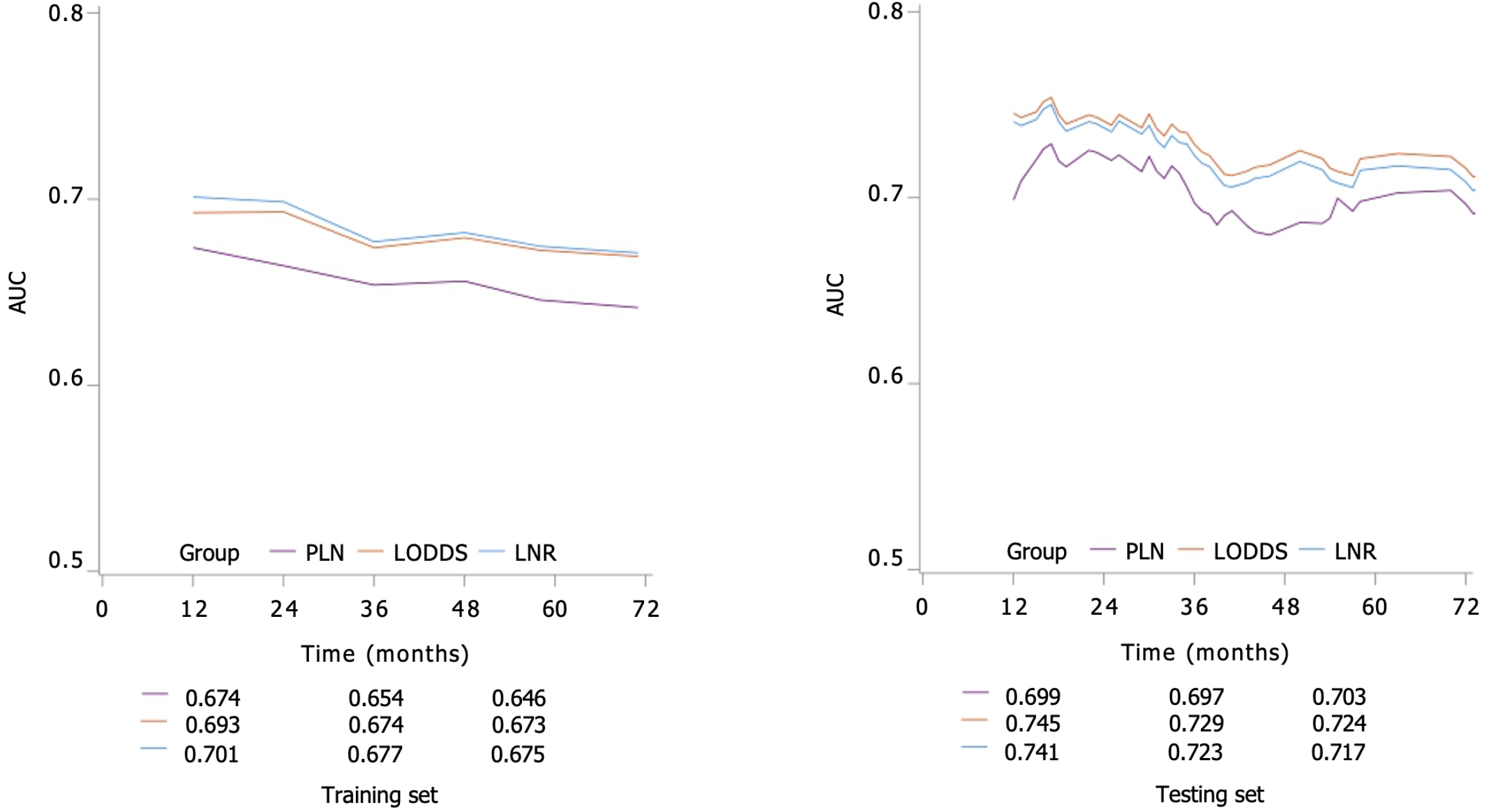

According to the C-index of the testing set (Table 3), we found that LODDS staging had a higher prognostic value for patients with colorectal NENs treated surgically than PLN staging, and LNR staging. In addition, we performed a time-related survival analysis. The findings revealed that, LODDS staging consistently exhibited higher AUC values compared to LNR or LODDS staging at the 1-, 2-, 3-, 4-, 5- and 6-year follow-ups (Figure 2).

| Variables | Training set | Testing set |

| C-index (95%CI) | C-index (95%CI) | |

| PLN staging | 0.620 (0.593-0.648) | 0.648 (0.608-0.689) |

| LNR staging | 0.645 (0.618-0.672) | 0.670 (0.630-0.710) |

| LODDS staging | 0.643 (0.615-0.670) | 0.675 (0.634-0.715) |

A subgroup analysis was conducted to assess the predictive significance of various lymph node staging systems in patients with colorectal NENs treated surgically who were categorized according to G staging (Table 4). The results showed that LODDS staging consistently had a higher prognostic value in patients with colorectal NENs treated surgically who were G (I + II) and G (III + IV) than PLN staging, and LNR staging.

| G stage | C-index (95%CI) |

| I + II | |

| PLN staging | 0.545 (0.464-0.627) |

| LNR staging | 0.633 (0.540-0.726) |

| LODDS staging | 0.638 (0.545-0.730) |

| III + IV | |

| PLN staging | 0.616 (0.564-0.668) |

| LNR staging | 0.637 (0.585-0.688) |

| LODDS staging | 0.638 (0.587-0.689) |

The prognosis of NENs could be influenced by the presence of lymph node metastasis[3,14]. Different staging systems for lymph nodes have been suggested, and are extensively employed in predicting the prognosis of NENs[15]. In this study, we examined the associations of PLN, LNR, and LODDS with the prognosis of patients with colorectal NENs treated surgically, and compared the predictive values of three staging systems. It was found that PLN, LNR, and LODDS staging systems were correlated with the death risk of colorectal NENs patients. After comparison, we concluded that the LODDS staging system had a higher prognostic value for colorectal NEN patients compared to the other two staging systems.

In this analysis, the mortality rate of patients with colorectal NENs treated surgically was 54.86%. We also found that the mean age of patients was 63.79 years. Regarding treatment options, only a minority of patients with colorectal NENs who underwent surgical intervention (4.92%) opted for radiation therapy[1]. It is widely acknowledged that the staging of PLN solely relies on the quantity of PLN, without taking into account the number of examined lymph nodes[16]. However, patients with an equal number of PLN may exhibit varying prognoses based on their respective counts of examined lymph nodes[17]. The practical application of PLN staging remains controversial. For example, Partelli et al[18] pointed out that the number of PLN could be used to predict the recurrence for pancreatic NENs. Moreover, the number of PLN was considered as an independent prognostic factor in colon NETs[13]. In the study of Huang et al[19], they demonstrated that LNR was a more promising prognostic factor for patients with testicular germ cell tumors than PLN. While considering both the quantity of PLN and the number of examined lymph nodes, LNR staging is taken into account[20]. Although it reduces the likelihood of staging migration caused by an inadequate count of examined lymph nodes, LNR staging does not seem to be applicable to predicting the patient prognosis when there are no PLNs present; and there may be differences in patients’ prognosis when the LNR is the same (e.g., 1/1 vs 10/10)[9,21]. LODDS staging, as a new method to assess the status of lymph nodes, has also been shown to have a better prognostic value than other staging systems[22,23]. The study conducted by Li et al[24] found a significant correlation between the LODDS staging system and postoperative outcomes in patients diagnosed with distal cholangiocarcinoma; the LODDS staging system was demonstrated better performance compared to both PLN staging and LNR staging; and additionally, they also established a prognostic nomogram using the LODDS staging system to predict the overall survival of individuals with distal cholangiocarcinoma[24]. Conversely, PLN staging might offer greater accuracy in predicting the survival of Pancreatic NENs compared to LNR and LODDS staging systems[11]. However, there has been limited researches conducted on evaluating the correlation of LNR and LODDS with the prognosis of colorectal NENs treated surgically. Additionally, there is a lack of comparative analysis regarding the predictive efficacy of these three staging systems on colorectal NENs.

In the present study, we utilized X-tile software for the purpose of categorizing the LNR, PLN, and LODDS. The results of unadjusted and adjusted analyses implied that three staging systems were risk factors for patients with colorectal NENs treated surgically. When the PLN, LNR, and LODDS scores are higher, the prognosis of patients may be worse. These findings might indicate a positive correlation between the three staging systems and patients’ mortality. In addition, we conducted a comparison of the prognostic predictive capabilities among the three scoring systems. The LODDS staging system exhibited a higher C-index compared to the other two staging systems in the testing set, and the consistent findings were observed in the subgroup analyses based on different G stages. The findings also indicated that the LODDS staging system exhibited potential superiority over PLN and LNR staging systems in terms of prognostic prediction for patients with colorectal NEN. Notably, this study observed a little difference in the predicted C-index of LODDS and LNR staging systems. There were 148 patients with PLN of 0 in this study, these patients had a similar prognosis, and all of them belonged to the LODDS tile 1 according to the LODDS staging. This could be the reason for the insignificant advantage of LODDS over LNR. More prospective studies are needed to confirm these findings and gain a deeper understanding of the underlying mechanisms.

This study investigated for the first time the relationship of three lymph node staging systems and the prognosis of colorectal NENs treated surgically; and we assessed and compared their respective prognostic capabilities. However, this study still has some limitations. First, the participants for our research were from the public SEER database that did not record patients’ symptoms[25], surgical margin status[26], and other indicators that might be associated with the prognosis of patients, which may also be confounding factors. Second, we excluded some patients with incomplete clinicopathological characteristic, such as patients with missing information about lymph nodes, PLN, tumor size or staging, which may cause some selection bias. It is critical to further validate these results with more prospective and large-sample studies in the future.

In short, our study revealed a significant association between LNR, PLN, and LODDS staging systems and the mortality risk among the colorectal NENs patients treated surgically. Furthermore, LODDS staging system might be potential to serve as a more effective prognostic indicator for colorectal NENs patients undergoing surgical treatment compared to PLN and LNR staging systems. This could offer valuable insights into the significance of various lymph node staging systems in predicting the prognosis of colorectal NENs patients treated surgically.

Colorectal neuroendocrine neoplasms (NENs) are a rare malignancy that exhibit a poor prognosis when lymph node metastasis occurs, which greatly reduces the survival rates of patients. Few studies have investigated the predictive significance of lymph node ratio (LNR), positive lymph node (PLN), and log odds of PLNs (LODDS) staging systems for colorectal NENs.

In this study, we investigated the predictive values of various lymph node staging systems on the prognosis of colorectal NENs treated surgically, and compare their predictive values, providing a reference for the improvement of lymph node staging of colorectal NENs.

To investigate the predictive values of LNR, PLN, and LODDS staging systems on the prognosis of colorectal NENs treated surgically, and compare their predictive values.

The present study utilized data extracted from a publicly available Surveillance, Epidemiology, and End Results database. X-tile software was utilized to identify most suitable thresholds for categorizing the LNR, PLN, and LODDS. We employed multivariate cox analysis to assess the associations of LNR, PLN, and LODDS with the prognosis of colorectal NENs. C-index was used for assessing the predictive effectiveness.

A total of 895 patients with colorectal NENs treated surgically were selected for this study. The training set comprised 627 patients, while the testing set consisted of 268 patients. After adjusting all confounding factors, PLN, LNR, and LODDS staging systems were linked with mortality in patients with colorectal NENs treated surgically. We found that LODDS staging had a higher prognostic value for patients with colorectal NENs treated surgically than PLN and LNR staging systems.

LNR, PLN, and LODDS were found to significantly predict the prognosis of patients with colorectal NENs treated surgically. LODDS staging system might be potential to serve as a more effective prognostic indicator for colorectal NENs patients undergoing surgical treatment compared to PLN and LNR staging systems.

We analyzed the predictive values of various lymph node staging systems on the prognosis of colorectal NENs treated surgically. After performing validation, LODDS staging system might be potential to serve as a more effective prognostic indicator for colorectal NENs patients undergoing surgical treatment compared to PLN and LNR staging systems. This could offer valuable insights into the significance of various lymph node staging systems in predicting the prognosis of colorectal NENs patients treated surgically.

Provenance and peer review: Unsolicited article; Externally peer reviewed.

Peer-review model: Single blind

Specialty type: Oncology

Country/Territory of origin: China

Peer-review report’s scientific quality classification

Grade A (Excellent): A

Grade B (Very good): 0

Grade C (Good): 0

Grade D (Fair): 0

Grade E (Poor): 0

P-Reviewer: Stan FG, Romania S-Editor: Chen YL L-Editor: A P-Editor: Zhang XD

| 1. | Wang Z, An K, Li R, Liu Q. Tumor Macroscopic Morphology Is an Important Prognostic Factor in Predicting Chemotherapeutic Efficacy and Clinical Outcomes of Patients With Colorectal Neuroendocrine Neoplasms, One Multicenter Retrospective Cohort Study. Front Endocrinol (Lausanne). 2021;12:801741. [PubMed] [DOI] [Cited in This Article: ] [Cited by in Crossref: 3] [Cited by in F6Publishing: 1] [Article Influence: 0.3] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 2. | Kooyker AI, Verbeek WH, van den Berg JG, Tesselaar ME, van Leerdam ME. Change in incidence, characteristics and management of colorectal neuroendocrine tumours in the Netherlands in the last decade. United European Gastroenterol J. 2020;8:59-67. [PubMed] [DOI] [Cited in This Article: ] [Cited by in Crossref: 9] [Cited by in F6Publishing: 19] [Article Influence: 3.8] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 3. | Wu Z, Wang Z, Zheng Z, Bi J, Wang X, Feng Q. Risk Factors for Lymph Node Metastasis and Survival Outcomes in Colorectal Neuroendocrine Tumors. Cancer Manag Res. 2020;12:7151-7164. [PubMed] [DOI] [Cited in This Article: ] [Cited by in Crossref: 4] [Cited by in F6Publishing: 8] [Article Influence: 2.0] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 4. | Zheng X, Wu M, Er L, Deng H, Wang G, Jin L, Li S. Risk factors for lymph node metastasis and prognosis in colorectal neuroendocrine tumours. Int J Colorectal Dis. 2022;37:421-428. [PubMed] [DOI] [Cited in This Article: ] [Cited by in Crossref: 1] [Cited by in F6Publishing: 1] [Article Influence: 0.5] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 5. | Ramage JK, Valle JW, Nieveen van Dijkum EJM, Sundin A, Pascher A, Couvelard A, Kloeppel G; the ENETS 2016 Munich Advisory Board Participants; ENETS 2016 Munich Advisory Board Participants. Colorectal Neuroendocrine Neoplasms: Areas of Unmet Need. Neuroendocrinology. 2019;108:45-53. [PubMed] [DOI] [Cited in This Article: ] [Cited by in Crossref: 16] [Cited by in F6Publishing: 18] [Article Influence: 3.6] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 6. | Amin MB, Greene FL, Edge SB, Compton CC, Gershenwald JE, Brookland RK, Meyer L, Gress DM, Byrd DR, Winchester DP. The Eighth Edition AJCC Cancer Staging Manual: Continuing to build a bridge from a population-based to a more "personalized" approach to cancer staging. CA Cancer J Clin. 2017;67:93-99. [PubMed] [DOI] [Cited in This Article: ] [Cited by in Crossref: 2341] [Cited by in F6Publishing: 3278] [Article Influence: 468.3] [Reference Citation Analysis (2)] |

| 7. | Li Destri G, La Greca G, Pesce A, Conti E, Puleo S, Portale TR, Scilletta R, Piazza M. Lymph node ratio and liver metachronous metastases in colorectal cancer. Ann Ital Chir. 2019;90:275-280. [PubMed] [Cited in This Article: ] |

| 8. | Zhang MR, Xie TH, Chi JL, Li Y, Yang L, Yu YY, Sun XF, Zhou ZG. Prognostic role of the lymph node ratio in node positive colorectal cancer: a meta-analysis. Oncotarget. 2016;7:72898-72907. [PubMed] [DOI] [Cited in This Article: ] [Cited by in Crossref: 23] [Cited by in F6Publishing: 24] [Article Influence: 4.0] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 9. | Occhionorelli S, Andreotti D, Vallese P, Morganti L, Lacavalla D, Forini E, Pascale G. Evaluation on prognostic efficacy of lymph nodes ratio (LNR) and log odds of positive lymph nodes (LODDS) in complicated colon cancer: the first study in emergency surgery. World J Surg Oncol. 2018;16:186. [PubMed] [DOI] [Cited in This Article: ] [Cited by in Crossref: 13] [Cited by in F6Publishing: 19] [Article Influence: 3.2] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 10. | Pei JP, Zhao ZM, Sun Z, Gu WJ, Zhu J, Ma SP, Liang Y, Guo R, Zhang R, Zhang CD. Development and validation of a novel classification scheme for combining pathological T stage and log odds of positive lymph nodes for colon cancer. Eur J Surg Oncol. 2022;48:228-236. [PubMed] [DOI] [Cited in This Article: ] [Cited by in Crossref: 2] [Cited by in F6Publishing: 2] [Article Influence: 0.7] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 11. | Gao B, Zhou D, Qian X, Jiang Y, Liu Z, Zhang W, Wang W. Number of Positive Lymph Nodes Is Superior to LNR and LODDS for Predicting the Prognosis of Pancreatic Neuroendocrine Neoplasms. Front Endocrinol (Lausanne). 2021;12:613755. [PubMed] [DOI] [Cited in This Article: ] [Cited by in Crossref: 3] [Cited by in F6Publishing: 2] [Article Influence: 0.7] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 12. | Yu H, Huang T, Feng B, Lyu J. Deep-learning model for predicting the survival of rectal adenocarcinoma patients based on a surveillance, epidemiology, and end results analysis. BMC Cancer. 2022;22:210. [PubMed] [DOI] [Cited in This Article: ] [Cited by in Crossref: 1] [Cited by in F6Publishing: 17] [Article Influence: 8.5] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 13. | Fields AC, McCarty JC, Lu P, Vierra BM, Pak LM, Irani J, Goldberg JE, Bleday R, Chan J, Melnitchouk N. Colon Neuroendocrine Tumors: A New Lymph Node Staging Classification. Ann Surg Oncol. 2019;26:2028-2036. [PubMed] [DOI] [Cited in This Article: ] [Cited by in Crossref: 6] [Cited by in F6Publishing: 6] [Article Influence: 1.2] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 14. | Li X, Shao L, Lu X, Yang Z, Ai S, Sun F, Wang M, Guan W, Liu S. Risk factors for lymph node metastasis in gastric neuroendocrine tumor: a retrospective study. BMC Surg. 2021;21:174. [PubMed] [DOI] [Cited in This Article: ] [Cited by in Crossref: 1] [Cited by in F6Publishing: 1] [Article Influence: 0.3] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 15. | Jiang S, Zhao L, Xie C, Su H, Yan Y. Prognostic Performance of Different Lymph Node Staging Systems in Patients With Small Bowel Neuroendocrine Tumors. Front Endocrinol (Lausanne). 2020;11:402. [PubMed] [DOI] [Cited in This Article: ] [Cited by in Crossref: 6] [Cited by in F6Publishing: 6] [Article Influence: 1.5] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 16. | Shang X, Li Z, Lin J, Yu H, Zhao C, Wang H, Sun J. Incorporating the Number of PLN into the AJCC Stage Could Better Predict the Survival for Patients with NSCLC: A Large Population-Based Study. J Oncol. 2020;2020:1087237. [PubMed] [DOI] [Cited in This Article: ] [Cited by in Crossref: 1] [Cited by in F6Publishing: 1] [Article Influence: 0.3] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 17. | Feinstein AR, Sosin DM, Wells CK. The Will Rogers phenomenon. Stage migration and new diagnostic techniques as a source of misleading statistics for survival in cancer. N Engl J Med. 1985;312:1604-1608. [PubMed] [DOI] [Cited in This Article: ] [Cited by in Crossref: 1124] [Cited by in F6Publishing: 1108] [Article Influence: 28.4] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 18. | Partelli S, Javed AA, Andreasi V, He J, Muffatti F, Weiss MJ, Sessa F, La Rosa S, Doglioni C, Zamboni G, Wolfgang CL, Falconi M. The number of positive nodes accurately predicts recurrence after pancreaticoduodenectomy for nonfunctioning neuroendocrine neoplasms. Eur J Surg Oncol. 2018;44:778-783. [PubMed] [DOI] [Cited in This Article: ] [Cited by in Crossref: 42] [Cited by in F6Publishing: 42] [Article Influence: 7.0] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 19. | Huang C, Long Q, Pan Y, Wu L, Wang X, Xu H, Zheng F. Lymph Node Ratio Rather Than Positive Lymph Node Counts Has Better Prognostic Value in Patients With Testicular Germ Cell Tumors. Technol Cancer Res Treat. 2021;20:1533033820979702. [PubMed] [DOI] [Cited in This Article: ] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 20. | Lei BW, Hu JQ, Yu PC, Wang YL, Wei WJ, Zhu J, Shi X, Qu N, Lu ZW, Ji QH. Lymph node ratio (LNR) as a complementary staging system to TNM staging in salivary gland cancer. Eur Arch Otorhinolaryngol. 2019;276:3425-3434. [PubMed] [DOI] [Cited in This Article: ] [Cited by in Crossref: 6] [Cited by in F6Publishing: 7] [Article Influence: 1.4] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 21. | Zhou YY, Du XJ, Zhang CH, Aparicio T, Zaanan A, Afchain P, Chen LP, Hu SK, Zhang PC, Wu M, Zhang QW, Wang H. Comparison of three lymph node staging schemes for predicting the outcome in patients with small bowel adenocarcinoma: A population-based cohort and international multicentre cohort study. EBioMedicine. 2019;41:276-285. [PubMed] [DOI] [Cited in This Article: ] [Cited by in Crossref: 13] [Cited by in F6Publishing: 15] [Article Influence: 3.0] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 22. | Xu T, Zhang L, Yu L, Zhu Y, Fang H, Chen B, Zhang H. Log odds of positive lymph nodes is an excellent prognostic factor for patients with rectal cancer after neoadjuvant chemoradiotherapy. Ann Transl Med. 2021;9:637. [PubMed] [DOI] [Cited in This Article: ] [Cited by in Crossref: 5] [Cited by in F6Publishing: 9] [Article Influence: 3.0] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 23. | Tang J, Jiang S, Gao L, Xi X, Zhao R, Lai X, Zhang B, Jiang Y. Construction and Validation of a Nomogram Based on the Log Odds of Positive Lymph Nodes to Predict the Prognosis of Medullary Thyroid Carcinoma After Surgery. Ann Surg Oncol. 2021;28:4360-4370. [PubMed] [DOI] [Cited in This Article: ] [Cited by in Crossref: 15] [Cited by in F6Publishing: 24] [Article Influence: 8.0] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 24. | Li R, Lu Z, Sun Z, Shi X, Li Z, Shao W, Zheng Y, Song J. A Nomogram Based on the Log Odds of Positive Lymph Nodes Predicts the Prognosis of Patients With Distal Cholangiocarcinoma After Surgery. Front Surg. 2021;8:757552. [PubMed] [DOI] [Cited in This Article: ] [Cited by in Crossref: 1] [Cited by in F6Publishing: 1] [Article Influence: 0.3] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 25. | Holtedahl K, Borgquist L, Donker GA, Buntinx F, Weller D, Campbell C, Månsson J, Hammersley V, Braaten T, Parajuli R. Symptoms and signs of colorectal cancer, with differences between proximal and distal colon cancer: a prospective cohort study of diagnostic accuracy in primary care. BMC Fam Pract. 2021;22:148. [PubMed] [DOI] [Cited in This Article: ] [Cited by in Crossref: 3] [Cited by in F6Publishing: 21] [Article Influence: 7.0] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 26. | She WH, Cheung TT, Ma KW, Tsang SHY, Dai WC, Chan ACY, Lo CM. Relevance of chemotherapy and margin status in colorectal liver metastasis. Langenbecks Arch Surg. 2021;406:2725-2737. [PubMed] [DOI] [Cited in This Article: ] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |