Published online Jul 15, 2018. doi: 10.4251/wjgo.v10.i7.194

Peer-review started: February 7, 2018

First decision: March 7, 2018

Revised: May 25, 2018

Accepted: June 8, 2018

Article in press: June 9, 2018

Published online: July 15, 2018

To present patients who developed small-bowel malignancy at the level of the gastrointestinal anastomosis decades after a subtotal gastrectomy for ulcer, to review relevant literature, and to attempt to interpret the reasons those cancers developed to these postsurgical non-gastric sights.

For the current retrospective study and review of literature, the surgical and histopathological records dated from January 1, 1993 to December 31, 2017 of our department were examined, searching for patients who have undergone surgical treatment of small-bowel malignancy to identify those who have undergone subtotal gastrectomy for benign peptic ulcer. A systematic literature search was also conducted using PubMed, EMBASE, and Cochrane Library to identify similar cases.

We identified three patients who had developed small-intestine malignancy at the level of the gastrointestinal anastomosis decades after a subtotal gastrectomy with Billroth II gastroenterostomy for benign peptic ulcer-two patients with adenocarcinoma originated in the Braun anastomosis and one patient with lymphoma of the efferent loop. All three patients were submitted to surgical resection of the tumor with Roux-en-Y reconstruction of the digestive tract. In the literature review, we only found one case of primary small-intestinal cancer that originated in the efferent loop after Billroth II gastrectomy because of duodenal ulcer but none reporting Braun anastomosis adenocarcinoma following partial gastrectomy for benign disease. We also did not find any case of efferent loop lymphoma following gastrectomy.

Anastomotic gastric cancer following distal gastrectomy for peptic ulcer is a well-established clinical entity. However, malignancies of the afferent or efferent loop of the gastrointestinal anastomosis are extremely uncommon. The substantial diversion of the potent carcinogenic pancreaticobiliary secretions through the Braun anastomosis and the stomach hypochlorhydria, allowing the formation of carcinogenic factors from food, are the two most prominent pathogenetic mechanisms for those tumors.

Core tip: Anastomotic gastric cancer following distal gastrectomy for peptic ulcer is a well-established clinical entity. However, malignancies of the afferent or efferent loop of the gastrointestinal anastomosis are extremely uncommon. In this paper, three patients who developed small-bowel malignancy at the level of the gastrointestinal anastomosis decades after a subtotal gastrectomy for ulcer are presented. The two most prominent pathogenetic mechanisms for those tumors are the stomach hypochlorhydria, allowing the formation of carcinogenic factors from food, and the substantial diversion of the potent carcinogenic pancreaticobiliary secretions through the Braun anastomosis.

- Citation: Kotidis E, Ioannidis O, Pramateftakis MG, Christou K, Kanellos I, Tsalis K. Atypical anastomotic malignancies of small bowel after subtotal gastrectomy with Billorth II gastroenterostomy for peptic ulcer: Report of three cases and review of the literature. World J Gastrointest Oncol 2018; 10(7): 194-201

- URL: https://www.wjgnet.com/1948-5204/full/v10/i7/194.htm

- DOI: https://dx.doi.org/10.4251/wjgo.v10.i7.194

Small-bowel malignancies are among the rarest cancers, accounting for only 2% of all gastrointestinal cancers, even though the organ makes up more than 70% of the length and 90% of the surface area of the gastrointestinal tract[1]. Approximately 60% of small-bowel tumors are malignant, and among those, adenocarcinomas comprise 35% to 50% of all cases, carcinoid tumors 20% to 40%, sarcomas 15%, and lymphomas 10% to 15%[2-5]. Anastomotic gastric cancer following distal gastrectomy for peptic ulcer disease has long been recognized. However, malignancies of the afferent or efferent loop of the gastrointestinal anastomosis are extremely uncommon.

In this paper, we present three patients who developed small-bowel malignancy at the level of the gastrointestinal anastomosis decades after a subtotal gastrectomy for ulcer, and we attempt to interpret the reason that those cancers developed to these postsurgical non-gastric sights.

For the current retrospective study and review of literature, the surgical and histopathological records dated from January 1, 1993 to December 31, 2017 of our department were examined, searching for patients who have undergone surgical treatment of small-bowel malignancy to identify those who have undergone subtotal gastrectomy for benign peptic ulcer. A systematic literature search was also conducted using PubMed, EMBASE, and Cochrane Library to identify similar cases.

A 79-year-old white male presented at our hospital because of chronic anemia appearing as syncope episodes for the last 4-5 mo. He also developed early satiety during this period. In the past, the patient had undergone a subtotal gastrectomy followed by Billroth II gastroenterostomy and Braun anastomosis for the treatment of peptic ulcer disease 22 years ago. His history also included hepatitis C, hypertension, type II diabetes, and myocardial infarction. His physical examination revealed an enlarged liver, and his blood tests showed a hypochromic anemia and slightly deranged liver function. The upper gastrointestinal endoscopy showed a lesion with an uneven surface at the Braun anastomosis. The computed tomography (CT) scan demonstrated liver cirrhosis and a tumor at the level of Braun anastomosis.

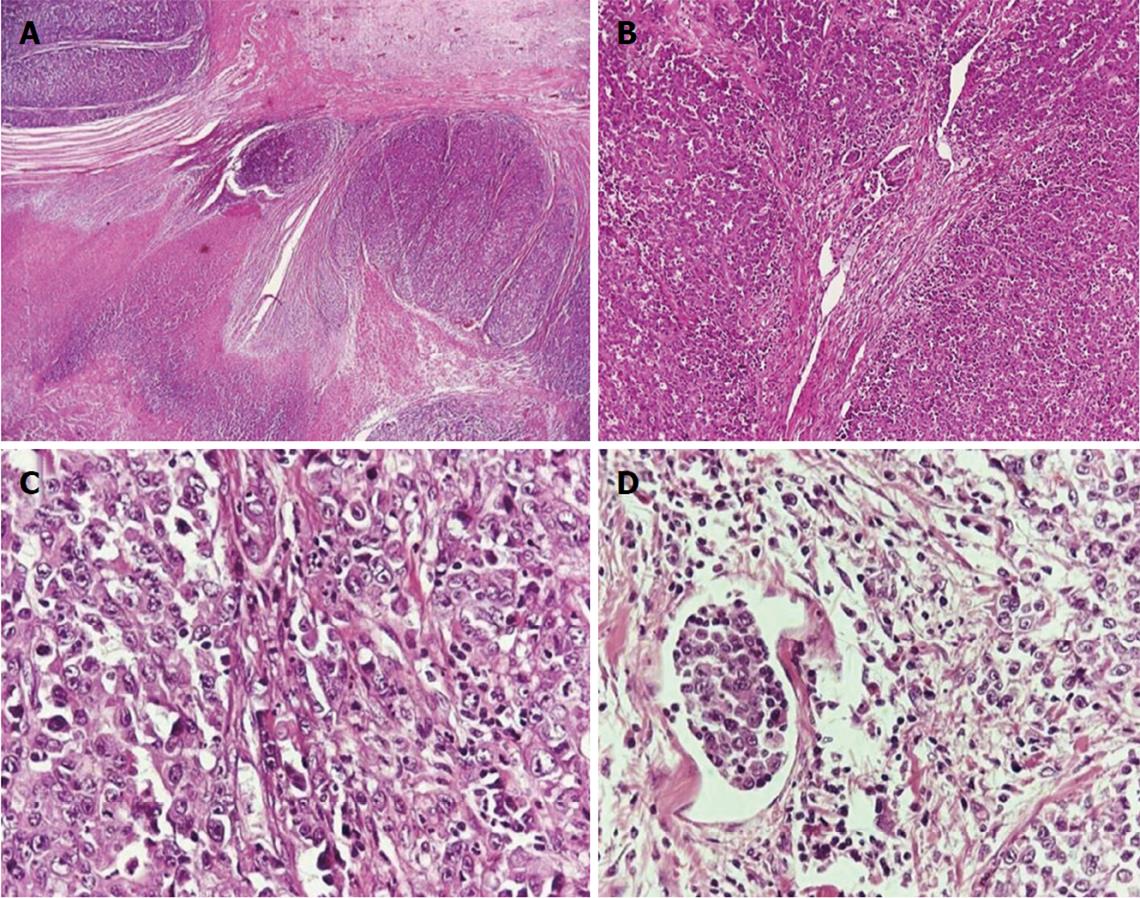

Hematoxylin- and eosin-stained sections from the lesion revealed the presence of a high-grade adenocarcinoma infiltrating the entire bowel wall and extending into the surrounding mesenteric fat tissue. Fibrotic bands in the histological sample resulted in the formation of nodular configurations. Only focally few tubular structures were identified. Foci of necrosis and lymphatic tumor emboli were also present. The neoplastic cells had hyperchromatic, irregular nuclei with prominent nucleoli, and they arranged mainly in a diffuse growth pattern (Figure 1).

The tumor, about 4 cm in diameter, was resected en bloc with the previous gastrojejunal anastomosis, and the gastrointestinal continuity was restored with a Roux-en-Y gastrojejunal anastomosis. The patient was discharged and is free of disease until today, 9 mo after surgery.

A 76-year-old man presented at our hospital with undefined abdominal discomfort and relapsing melenas for the last 2-3 mo. He also experienced a drop in hematocrit during this period. Prior surgical history included a subtotal gastrectomy because of a bleeding pyloric ulcer, followed by a Billroth II Hofmeister–Finsterer anastomosis and a jejunojejunostomy (Braun), approximately 30 years ago. His physical examination and laboratory tests were unremarkable except for the presence of anemia. Endoscopy showed a tumor at the Braun anastomosis that ended up being an adenocarcinoma. The abdominal CT showed only the Braun anastomosis tumor. He underwent a partial gastrectomy of the gastric pouch with resection of the Braun anastomosis and tumor, measuring 5 cm × 2 cm, and a Roux-en-Y reconstruction (Figure 2). The patient had a smooth postoperative course and 2.5 years after treatment is free of relapse.

Α 78-year-old man was referred to our hospital for hematemesis and melena. The patient had undergone a partial gastrectomy with Billroth II gastroenterostomy because of duodenal ulcer disease 30 years ago. His history, however, included splenectomy caused by trauma, cholecystectomy, and hypertension. His physical exam and blood tests were unremarkable except for the presence of a normocromic anemia. He underwent an upper-gastrointestinal endoscopy, which identified a sizable ulcer crater at the beginning of the efferent jejunal loop, about 4 cm from the anastomosis, with unsuccessful attempts of permanent hemostasis. A laparotomy was decided upon. A large tumor of the efferent jejunal loop was identified with multiple small infiltrations in the afferent loop of 15-20 cm. The rest of the small intestine was free. The Helicobacter pylori examination was positive. A segmental resection of the gastric pouch and the infiltrated jejunal loops was performed, followed by a Roux-en-Y reconstruction.

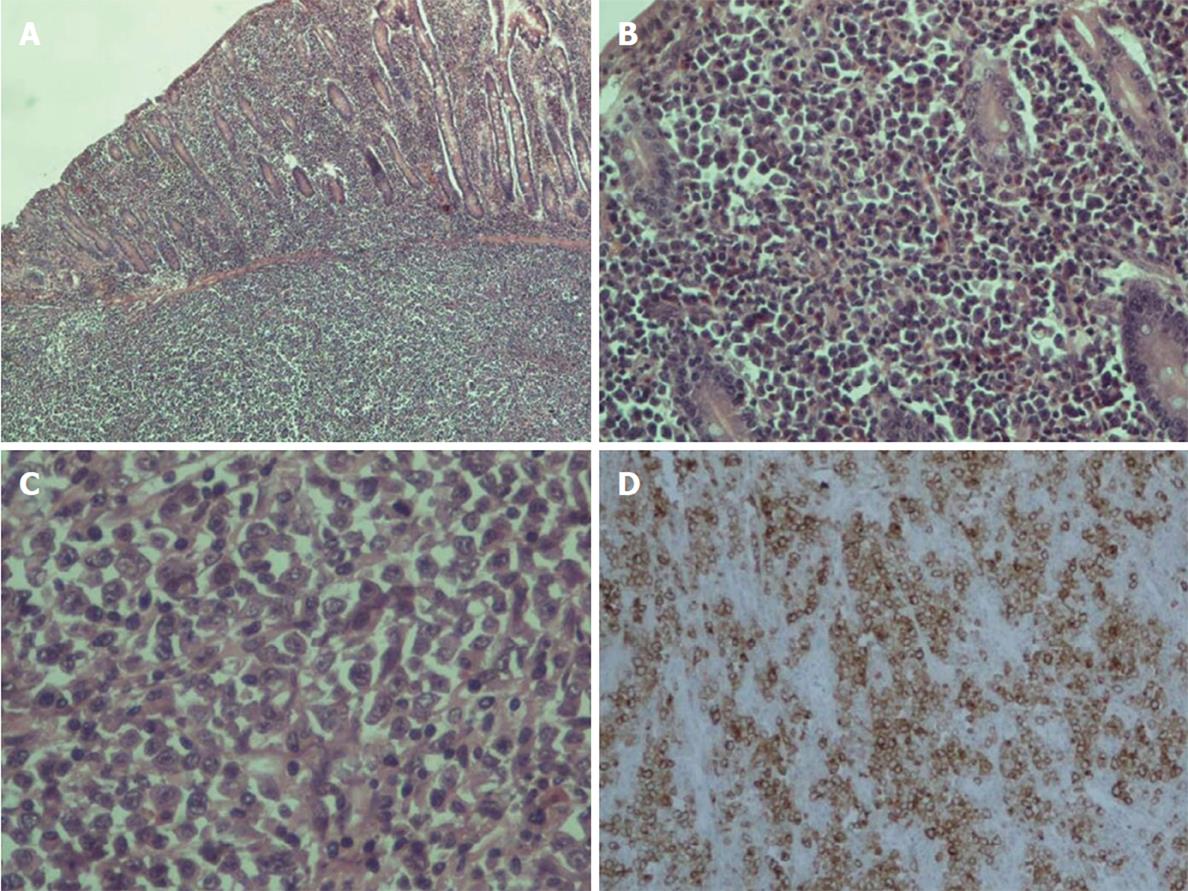

On histopathologic examination, the reported ulcer was part of a grayish intramural lesion that infiltrated the entire wall of the intestine. Microscopically, large undifferentiated neoplastic cells were widely disseminated. The cells contained a moderate amount of cytoplasm and sizable, oval, frequently irregular pleomorphic nuclei with multiple prominent nucleoli. Binucleate, abnormal multinucleate, and multilobed nuclei formats were observed (Figure 3). By immunohistochemistry, the large cells were strongly positive for CD30. They were also positive for vimentin, epithelial membrane antigen (EMA), CD7, CD43, and MUM1. Partial positivity was for the antigens CD138, p53, CD38, CD45RO (LCA), perforin, and AE1/AE3 (cytokeratin). The large cells were negative for the expression of CD2, CD3, CD5, CD4, CD8, ALK, CD56, CD20, CD79a, PAX5, CD45RA, TIA1, CD15, myeloperoxidase (MPO), lysozyme, and EBV-LMP1.

The findings are consistent with anaplastic large cell lymphoma (ALCL) ALK-negative (anaplastic lymphoma kinase), a rare type of non-Hodgkin lymphoma. The resection boundaries were free of neoplastic infiltration, and no lymph node involvement (17 in total) was found. The patient has been referred to the hematology department for further treatment and follow-up.

Small-bowel adenocarcinomas are relatively uncommon and have a slight male preponderance (3:2), and their peak incidence is the seventh decade of life[1]. They are believed to arise from premalignant adenomas[6]. They also have a predilection for the duodenum, with a marked decrease in frequency moving axially along the small bowel[1]. Knowing from physiology that this is exactly the effect of the distribution of ingested chemicals and the effect of gastric and pancreaticobiliary secretion on intestinal mucosa may indicate that these substances may have carcinogenic properties[4,5]. Furthermore, small-bowel adenocarcinoma is associated with Crohn’s disease (up to 100-fold risk), celiac disease, and familial polyposis syndrome, none of which were included in our patients’ history. There is not a specific complex of symptoms diagnostic for small-bowel cancer, but the most common are abdominal pain, nausea, obstruction symptoms, and weakness. Bleeding, either occult as melena like our first and second case or acute in the form of hematemesis like our 3rd case, is more uncommon[2,6].

Following distal gastrectomy for peptic ulcer disease, gastric cancer can develop, usually after years, in the gastric remnant[7]. A gastric remnant carcinoma is defined as a primary carcinoma arising in the stomach, remnant at least 5 years after previous partial gastrectomy for benign disease, most frequently peptic ulcer disease. The 5-year interval is necessary to avoid confusion with cancer recurrence after initial misdiagnosis. Several large prospective studies with long-term follow-up indicate that the relative risk for this gastric neoplasm development is not increased for up to 15 years after gastric resection[8,9], likely because of surgical removal of mucosa at risk for gastric cancer development, followed by modest increases in cancer risk (three times the control value) observed only after 20 years[10-12]. Recently, conservative medical therapy has displaced partial gastrectomy for the treatment of ulcer. Nevertheless, since surgical therapy was still used frequently for the treatment of gastroduodenal ulcer disease until the late 1970s and early 1980s and gastric remnant carcinoma develops with a time interval of 20–40 years, the surgeon will be confronted with this disease regularly until at least 2020[13]. Stage for stage, the prognosis for gastric stump cancer is similar to proximal gastric cancer[14].

Additionally, Ravi Thiruvengadam et al[15] had attempted to estimate the risk of cancer at gastrointestinal spots other than the stomach, such as the small and large intestines, the esophagus, and the gallbladder, after gastric surgery for benign disease. There was no strong evidence for an increased risk of any gastrointestinal cancer following gastric surgery. However, after 10 years, Staël von Holstein et al[16] showed that there is an increased risk for nongastric gastrointestinal cancer, but similar to gastric remnant carcinoma, that risk emerges only 20 years postoperatively. The abovementioned studies concluded that all patients should be screened after an interval of 15-20 years after the distal gastrectomy.

With regard to the pathogenesis of gastric remnant cancer, the predominant factors presumed to be responsible for it are duodenogastric reflux and hypochlorhydria. Chronic duodenogastric reflux causes various histological alterations at the gastric stump, such as intestinal metaplasia, dysplasia, and adenoma. The gastrojejunal anastomosis is considered the most common site of gastric remnant carcinoma because the quantity and concentration of gastroduodenal reflux are highest here. Both bile acids and pancreatic juice seem to be carcinogenic factors, even though we do not know exactly which components are responsible. Bile acids, such as deoxycholic bile acid and nitrated derivatives of glycocholic and taurocholic bile acids, seem to have a carcinogenic influence at the gastric stump mucosa[5,17-19]. Braun, in 1893, introduced the jejunojejunal anastomosis between the afferent and efferent small intestine loops immediately distal to a gastrointestinal anastomosis. Using radionuclide biliary scanning, Vogel et al[20] found that Braun enteroenterostomy adequately diverts a substantial amount of bile from the stomach in patients undergoing gastroenterostomy or Billroth II resection. Hence, because of the skipping of the ascending (or afferent) and descending (or efferent) jejunal loop (approximately 50 cm), the pancreaticobiliary fluids come less in contact with the gastric stump and more with the Braun anastomosis and the efferent limb distal to it. Therefore, the increased exposure of the latter surfaces to carcinogenic bile acids, not only for the gastric stump mucosa but also for the small intestine[1,4], is most likely the underlying pathophysiologic mechanism that enables the Braun anastomosis mucosa to become dysplastic and neoplastic before the gastric stump mucosa does.

Because of the resection of the gastrin-producing cells after a distal gastrectomy, the gastric stump mucosa usually becomes atrophic. This atrophy causes hypochlorhydria, and thus, the pH value rises, resulting in bacterial population growth. Some of these bacteria reduce dietary nitrates to nitrites, which, in the presence of substrates, such as food proteins, can lead to the formation of potent carcinogens[13,21,22]. If those carcinogens are absorbed systemically, then that supports the observation of Staël von Holstein et al[16] that after a gastrectomy for ulcer, there is an increased risk of developing a carcinoma in a location other than the gastric stump, just like in our patients.

We reviewed the literature and found some similar cases of gastrointestinal cancer near but not on the anastomosis after partial gastrectomy for benign disease. Takebayashi et al[23] presented a case of primary small-intestinal cancer that originated in the efferent loop after the Billroth II gastrectomy that occurred 32 years earlier because of duodenal ulcer. Rose et al[24] reported a case of gastric adenocarcinoma arising at the duodenal stump 40 years after a Billroth II partial gastrectomy for benign condition. Table 1 summarizes the reported cases in the literature and our cases with atypical anastomotic malignancies of small bowel after subtotal gastrectomy with Billorth II gastroenterostomy for peptic ulcer. To our knowledge, our patients are the first reported cases of Braun anastomosis adenocarcinoma following partial gastrectomy for benign disease.

| Case | Sex | Age | Tumor | Origin | Clinical data | Laboratory data | Treatment | Outcome | Ref. |

| 1 | M | 79 | Small intestine adenocarcinoma | Braun anastomosis after 22 yr from gastrectomy | Syncope episodes, early satiety | Hypochromic anemia | En block resection and Royx-en-Y gastrojejunal anastomosis | Disease free 9 mo | Kotidis, 2018 |

| 2 | M | 76 | Small intestine adenocarcinoma | Braun anastomosis after 30 yr from gastrectomy | Abdominal Discomfort, Melenas | Anemia | En block resection and Royx-en-Y gastrojejunal anastomosis | Disease free 2.5 yr | Kotidis, 2018 |

| 3 | M | 78 | Anaplastic large cell lymphoma | Efferent loop after 30 yr from gastrectomy | Hematemesis, melena | Normochromic anemia | En block resection and Royx-en-Y gastrojejunal anastomosis | Referred to hematology department | Kotidis, 2018 |

| 4 | M | 79 | Small intestine adenocarcinoma | Efferent loop after 32 yr from gastrectomy | Asymptomatic | Anemia | Jejunectomy | Disease free at 17 mo | [23] |

| 5 | F | 79 | Duodenal adenocarcinoma | Duodenal stamp 40 yr after gastrectomy | Fatigue and weakness for 3 mo | Anemia | Resection of afferent limp | Disease free at 12 mo | [24] |

Lymphomas affect the small bowel as a manifestation of systemic disseminated disease, or they may be primarily present[3]. Non-Hodgkin lymphomas (NHLs) of the gastrointestinal tract represent 4% to 20% of all NHLs[25]. Of all gastrointestinal NHLs, 25% to 35% of ca–ses occur within the small bowel, in which lymphomas parallel the distribution of lymphoid follicles, resulting in the ileum being the most common site of involvement[1]. Anaplastic large cell lymphoma (ALCL) is a distinctive subtype of NHL. It accounts for approximately 2% of all cases of NHL. It belongs to the NHL subcategory of peripheral T-cell lymphomas (PTCL). It is made up of either malignant T-cells or “null-lymphocytes” (lack both B- and T-cell markers). The presence of the protein CD30 antigen on the surface of lymphoma cells is the hallmark of the disease[26]. Usually, ALCL is negative for cytokeratin. The positive cytokeratin AE1/AE3 cells in our case were considered remnant epithelial cells. The ALK-negative subtype of ALCL appears more commonly in the elderly, is more aggressive, and belongs to the systemic form of ALCL[27], which typically presents with painless enlarged lymph nodes and extranodal site involvement, most commonly including the skin, bones, soft tissues, and lungs. The gastrointestinal tract being involved in our case is rare[27], and even though, in the literature, rare cases of gastrointestinal ALCL at various spots, including the small intestine, have been documented[28-30], as far as we know, this is the first case reported at the efferent loop of a Billroth II gastroenterostomy decades after operation.

In conclusion, the “by-pass” path of the bile made by a Braun anastomosis added to a Billroth II gastrectomy is the most prevalent hypothesis for the development of the two adenocarcinomas at the specific spot. Much more needs to be discovered about the ALCL ALK-negative type of lymphoma to make assumptions since it has not been studied for more than 20 years. However, we cannot be certain that the appearance of those small-intestinal tumors at those spots were directly related to the operations that occurred decades ago.

Despite the fact that the small intestine makes up more than 90% of the surface area and 70% of the length of the gastrointestinal tract, small bowel malignancies are among the rarest cancers. Anastomotic gastric cancer following distal gastrectomy for peptic ulcer is a well-established clinical entity. However, malignancies of the afferent or efferent loop of the gastrointestinal anastomosis are extremely uncommon.

To present patients who developed small-bowel malignancy at the level of the gastrointestinal anastomosis decades after a subtotal gastrectomy for ulcer.

In this paper, we present three patients who developed small-bowel malignancy at the level of the gastrointestinal anastomosis decades after a subtotal gastrectomy for ulcer, to review relevant literature, and to interpret the reason that those cancers developed to these postsurgical nongastric sights.

For the current retrospective study and review of literature, the surgical and histopathological records of our department were examined, searching for patients who have undergone surgical treatment of small-bowel malignancy to identify those who have undergone subtotal gastrectomy for benign peptic ulcer. A systematic literature search was also conducted using PubMed, EMBASE, and Cochrane Library to identify similar cases.

We identified three patients who had developed small-intestine malignancy at the level of the gastrointestinal anastomosis decades after a subtotal gastrectomy with Billroth II gastroenterostomy for benign peptic ulcer-two patients with adenocarcinoma originated in the Braun anastomosis and one patient with lymphoma of the efferent loop. All three patients were submitted to surgical resection of the tumor with Roux-en-Y reconstruction of the digestive tract. In the literature review, we only found one case of primary small-intestinal cancer that originated in the efferent loop after Billroth II gastrectomy because of duodenal ulcer but none reporting Braun anastomosis adenocarcinoma following partial gastrectomy for benign disease. We also did not find any case of efferent loop lymphoma following gastrectomy.

Anastomotic gastric cancer following distal gastrectomy for peptic ulcer is a well-established clinical entity. However, malignancies of the afferent or efferent loop of the gastrointestinal anastomosis are extremely uncommon. The substantial diversion of the potent carcinogenic pancreaticobiliary secretions through the Braun anastomosis and the stomach hypochlorhydria, allowing the formation of carcinogenic factors from food, are the two most prominent pathogenetic mechanisms for those tumors.

The “by-pass” path of the bile made by a Braun anastomosis added to a Billroth II gastrectomy is the most prevalent hypothesis for the development of the two adenocarcinomas at the specific spot. Much more needs to be discovered about the ALCL ALK-negative type of lymphoma to make assumptions since it has not been studied for more than 20 years. However, we cannot be certain that the appearance of those small-intestinal tumors at those spots had a direct relation to the operations that occurred decades ago.

Manuscript source: Invited manuscript

Specialty type: Oncology

Country of origin: Greece

Peer-review report classification

Grade A (Excellent): 0

Grade B (Very good): B, B

Grade C (Good): C, C

Grade D (Fair): D

Grade E (Poor): 0

P- Reviewer: Dinç T, Kai K, Liu D, Luo HS, Sukocheva OA S- Editor: Ji FF L- Editor: Filipodia E- Editor: Tan WW

| 1. | Turner DJ, Jain A, Bass BL. Small-intestinal Neoplasms. Greenfield’s Surgery: Scientific Principles Practice. 5th ed. Philadelphia: Lippincott Williams Wilkings 2010; 784-797. [Cited in This Article: ] |

| 2. | Somasundar PS, Fisichella PM, Espat NJ. Malignant Neoplasms of the Small Intestine. Available from: http://emedicine.medscape.com/article/282684-overview. [Cited in This Article: ] |

| 3. | Tavakkoli A, Ashley SW, Zinner MJ. Small Intestine. Schwartz’s Principles of Surgery. 10th ed. Columbus: McGraw-Hill Education 2014; 1137-1174. [Cited in This Article: ] |

| 4. | Allaix ME, Krane M, Fichera A. Small Bowel. Current Diagnosis and Treatment Surgery. 14th ed. Columbus: McGraw-Hill Education 2015; 657-685. [Cited in This Article: ] |

| 5. | Ross RK, Hartnett NM, Bernstein L, Henderson BE. Epidemiology of adenocarcinomas of the small intestine: is bile a small bowel carcinogen? Br J Cancer. 1991;63:143-145. [PubMed] [DOI] [Cited in This Article: ] [Cited by in Crossref: 82] [Cited by in F6Publishing: 91] [Article Influence: 2.8] [Reference Citation Analysis (1)] |

| 6. | Kummar S, Ciesielski TE, Fogarasi MC. Management of small bowel adenocarcinoma. Oncology (Williston Park). 2002;16:1364-1369; discussion 1370, 1372-1373. [PubMed] [Cited in This Article: ] |

| 7. | Kitagawa Y, Dempsey DT. Stomach. Schwartz’s Principles of Surgery. 10th ed. Columbus: McGraw-Hill Education 2014; 1035-1098. [Cited in This Article: ] |

| 8. | Fischer AB, Graem N, Jensen OM. Risk of gastric cancer after Billroth II resection for duodenal ulcer. Br J Surg. 1983;70:552-554. [PubMed] [DOI] [Cited in This Article: ] [Cited by in Crossref: 47] [Cited by in F6Publishing: 46] [Article Influence: 1.1] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 9. | Schafer LW, Larson DE, Melton LJ 3rd, Higgins JA, Ilstrup DM. The risk of gastric carcinoma after surgical treatment for benign ulcer disease. A population-based study in Olmsted County, Minnesota. N Engl J Med. 1983;309:1210-1213. [PubMed] [DOI] [Cited in This Article: ] [Cited by in Crossref: 106] [Cited by in F6Publishing: 105] [Article Influence: 2.6] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 10. | Minter RM. Gastric Neoplasms. Greenfield’s Surgery: Scientific Principles Practice. 5th ed. Philadelphia: Lippincott Williams Wilkings 2010; 722-736. [Cited in This Article: ] |

| 11. | La Vecchia C, Negri E, D’Avanzo B, Moller H, Franceschi S. Partial gastrectomy and subsequent gastric cancer risk. J Epidemiol Community Health. 1992;46:12-14. [PubMed] [DOI] [Cited in This Article: ] [Cited by in Crossref: 14] [Cited by in F6Publishing: 14] [Article Influence: 0.4] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 12. | Toftgaard C. Gastric cancer after peptic ulcer surgery. A historic prospective cohort investigation. Ann Surg. 1989;210:159-164. [PubMed] [DOI] [Cited in This Article: ] [Cited by in Crossref: 84] [Cited by in F6Publishing: 92] [Article Influence: 2.6] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 13. | Sinning C, Schaefer N, Standop J, Hirner A, Wolff M. Gastric stump carcinoma - epidemiology and current concepts in pathogenesis and treatment. Eur J Surg Oncol. 2007;33:133-139. [PubMed] [DOI] [Cited in This Article: ] [Cited by in Crossref: 79] [Cited by in F6Publishing: 90] [Article Influence: 5.0] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 14. | Newman E, Brennan MF, Hochwald SN, Harrison LE, Karpeh MS Jr. Gastric remnant carcinoma: just another proximal gastric cancer or a unique entity? Am J Surg. 1997;173:292-297. [PubMed] [DOI] [Cited in This Article: ] [Cited by in Crossref: 47] [Cited by in F6Publishing: 48] [Article Influence: 1.8] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 15. | Thiruvengadam R, Hench V, Melton LJ 3rd, DiMagno EP. Cancer of the nongastric hollow organs of the gastrointestinal tract after gastric surgery. Arch Intern Med. 1988;148:405-407. [PubMed] [DOI] [Cited in This Article: ] [Cited by in Crossref: 7] [Cited by in F6Publishing: 7] [Article Influence: 0.2] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 16. | Staël von Holstein C, Anderson H, Ahsberg K, Huldt B. The significance of ulcer disease on late mortality after partial gastric resection. Eur J Gastroenterol Hepatol. 1997;9:33-40. [PubMed] [DOI] [Cited in This Article: ] [Cited by in Crossref: 13] [Cited by in F6Publishing: 13] [Article Influence: 0.5] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 17. | Kondo K. Duodenogastric reflux and gastric stump carcinoma. Gastric Cancer. 2002;5:16-22. [PubMed] [DOI] [Cited in This Article: ] [Cited by in Crossref: 65] [Cited by in F6Publishing: 66] [Article Influence: 3.1] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 18. | Busby WF Jr, Shuker DE, Charnley G, Newberne PM, Tannenbaum SR, Wogan GN. Carcinogenicity in rats of the nitrosated bile acid conjugates N-nitrosoglycocholic acid and N-nitrosotaurocholic acid. Cancer Res. 1985;45:1367-1371. [PubMed] [Cited in This Article: ] |

| 19. | Schottenfeld D, Beebe-Dimmer JL, Vigneau FD. The epidemiology and pathogenesis of neoplasia in the small intestine. Ann Epidemiol. 2009;19:58-69. [PubMed] [DOI] [Cited in This Article: ] [Cited by in Crossref: 180] [Cited by in F6Publishing: 202] [Article Influence: 13.5] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 20. | Vogel SB, Drane WE, Woodward ER. Clinical and radionuclide evaluation of bile diversion by Braun enteroenterostomy: prevention and treatment of alkaline reflux gastritis. An alternative to Roux-en-Y diversion. Ann Surg. 1994;219:458-465; discussion 465-466. [PubMed] [DOI] [Cited in This Article: ] [Cited by in Crossref: 54] [Cited by in F6Publishing: 43] [Article Influence: 1.4] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 21. | Safatle-Ribeiro AV, Ribeiro U Jr, Reynolds JC. Gastric stump cancer: what is the risk? Dig Dis. 1998;16:159-168. [PubMed] [DOI] [Cited in This Article: ] [Cited by in Crossref: 52] [Cited by in F6Publishing: 52] [Article Influence: 2.0] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 22. | Muscroft TJ, Deane SA, Youngs D, Burdon DW, Keighley MR. The microflora of the postoperative stomach. Br J Surg. 1981;68:560-564. [PubMed] [DOI] [Cited in This Article: ] [Cited by in Crossref: 55] [Cited by in F6Publishing: 57] [Article Influence: 1.3] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 23. | Takebayashi M, Toyota N, Nozaka K, Wakatsuki T, Kamasako A, Tanida O. A Case of Primary Cancer of The Small Intestine Originated in The Efferent Loop after Billoth-II Reconstruction (in Japanese). Jpn J Gastroenterol Surg. 2008;41:335-340. [DOI] [Cited in This Article: ] [Cited by in Crossref: 1] [Cited by in F6Publishing: 1] [Article Influence: 0.1] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 24. | Rose JF, Stankova L, Glazer ES, Villar HV. Gastric Adenocarcinoma in the Duodenal Stump 40 Years After a Billroth II Partial Gastrectomy for Benign Indications. Gastrointest Cancer Res. 2012;5:141-143. [PubMed] [Cited in This Article: ] |

| 25. | Otter R, Bieger R, Kluin PM, Hermans J, Willemze R. Primary gastrointestinal non-Hodgkin’s lymphoma in a population-based registry. Br J Cancer. 1989;60:745-750. [PubMed] [DOI] [Cited in This Article: ] [Cited by in Crossref: 79] [Cited by in F6Publishing: 84] [Article Influence: 2.4] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 26. | Ferreri AJ, Govi S, Pileri SA, Savage KJ. Anaplastic large cell lymphoma, ALK-negative. Crit Rev Oncol Hematol. 2013;85:206-215. [PubMed] [DOI] [Cited in This Article: ] [Cited by in Crossref: 86] [Cited by in F6Publishing: 97] [Article Influence: 8.1] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 27. | Liu D, Furqan M, Urbanski C, Krishnan K. Anaplastic Large Cell Lymphoma. Available from: http://emedicine.medscape.com/article/208050-overview#a1. [Cited in This Article: ] |

| 28. | Galani K, Gurudu SR, Chen L, Kelemen K. Anaplastic Large Cell Lymphoma, ALK-Negative Presenting in the Rectum: A Case Report and Review of the Literature. Open J Pathol. 2013;3:37-40. [DOI] [Cited in This Article: ] [Cited by in Crossref: 3] [Cited by in F6Publishing: 3] [Article Influence: 0.3] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 29. | Ross CW, Hanson CA, Schnitzer B. CD30 (Ki-1)-positive, anaplastic large cell lymphoma mimicking gastrointestinal carcinoma. Cancer. 1992;70:2517-2523. [PubMed] [DOI] [Cited in This Article: ] [Cited by in F6Publishing: 1] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 30. | Carey MJ, Medeiros LJ, Roepke JE, Kjeldsberg CR, Elenitoba-Johnson KS. Primary anaplastic large cell lymphoma of the small intestine. Am J Clin Pathol. 1999;112:696-701. [PubMed] [DOI] [Cited in This Article: ] [Cited by in Crossref: 27] [Cited by in F6Publishing: 27] [Article Influence: 1.1] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |