Abstract

Summary

The relationship between asthma and the workplace is important to consider in all cases of adult asthma. Early identification of a cause in the workplace offers an opportunity to improve asthma control significantly and reduce the need for long-term medication if further exposures to the cause can be avoided. This typical but fictitious case is designed to give the reader clinical information in the order this would normally be received in clinical practice, with a real-time commentary about management decisions. Pertinent recent guidance is cited to stress the importance of evidence-based practice.

Similar content being viewed by others

Initial case information

A 43-year-old man with long-standing asthma comes for a consultation with you. He has just moved to your practice and all your information about him is not up to date. He has just returned from a 2-week holiday during which he felt ‘fantastic’ and ‘hardly needed my blue inhaler at all’. Overall, however, his asthma has been more difficult to control recently and he frequently has episodes of wheeze during the working day.

It appears that he understands his condition reasonably well, has good inhaler technique, and reports taking his prescribed prophylactic medication regularly. He is currently prescribed budesonide 400 μg twice daily, formoterol 12 μg twice daily, and as-required salbutamol.

Introduction

The potential relationship between asthma and the workplace is important to consider in all cases of asthma in adults of working age. Early identification of asthma caused by a substance in the workplace offers a potential opportunity to improve asthma control significantly and to reduce the need for long-term medication if further exposures to the cause can be avoided.

Occupational factors are estimated to account for about one in six cases of asthma in adults of working age, including new onset or recurrent disease, most commonly due to sensitisation, where an allergy to an inhaled workplace exposure has developed into asthma.1–3 Typical examples include allergy to flour dust or to isocyanate-based spray paints. In addition to individuals whose asthma has been caused by work, a further proportion of adults with asthma report that their symptoms are aggravated at work by various factors including dusts, cold temperatures, exercise, and stress (work-aggravated asthma; WAA).4 WAA is also occasionally referred to as work-exacerbated asthma (WEA).

Occupational asthma (OA) and WAA are both typified by work-related asthma symptoms (i.e. asthma symptoms that are either worse at work and/or better on days off and holidays). Both conditions also cause significant morbidity, increased healthcare utilisation, financial disadvantage, and a lower health-related quality of life.5–8 Both OA and WAA have been subject to recent review and guidance.1,2,4 It is important to try to distinguish these different types of asthma as case management may vary depending on whether the asthma is caused by or aggravated by something in the workplace. Essentially, a diagnosis of OA implies that further exposure to the causative agent, even at very low levels, will maintain the disease and make its treatment with standard therapies more difficult, as would attempts to reduce exposures without changing jobs. By contrast, WAA can often be managed by relatively minor changes in work tasks and workplace interventions and improved pharmacological management.

As OA is important to identify and manage, the British Thoracic Society (BTS) Standards of Care Committee produced a Standard of Care for OA in 2008,1 based on a systematic evidence review performed in 2004 by the British Occupational Health Research Foundation (BOHRF).3 This was recently updated in 2012 and is intended as a general standard for guiding care for this condition.2

WAA is the more common type of work-related asthma. Recently reviewed by Henneberger et al.4 and published as an American Thoracic Society statement, this was identified as occurring in a high proportion of workers with asthma with a median prevalence of 21.5%. In other words, one in five patients with asthma reports that their symptoms are worse at work. While such aggravation of asthma can be caused by exposure to allergens, it is generally associated with inhaling irritant chemicals, gases, and fumes (such as ammonia), general dusts, second-hand tobacco smoke, paints, and solvents. Unlike OA, WAA can also be caused by other factors in the workplace such as stress, humidity, and working in hot or cold environments. It is the general view that WAA should only be diagnosed once OA has been thought about and excluded.

Both documents2,3 focus on the need to make an early and accurate diagnosis, initially by taking a history from the patient of how asthma symptoms relate to work and by taking an appropriate occupational history to help identify the nature of workplace exposures where possible. This article is intended to update the reader in relation to these two areas, with particular relevance to a primary care context. Further investigations and advice relating to specialist referral will also be included.

History: work relation of asthma symptoms

A range of factors should be considered during any consultation relating to poor asthma control; these are detailed comprehensively in the latest BTS guidance.9 In adults of working age, this must include asking the patient about their current occupation, the nature of their work, and whether this involves exposures to any fumes, dusts, gases, or vapours.

In practice it may be difficult to distinguish between OA and WAA from the medical history alone. Table 1 details certain differences. Identifying the work relation of asthma symptoms is an important first step as their presence suggests that further assessment is likely to be needed.

The BTS Standard of Care1 recommends that all adults with possible asthma, new onset asthma, reappearance of childhood asthma, deterioration in asthma control or unexplained airways obstruction (forced expiratory volume in one second/forced vital capacity <0.70) should be asked about the relationship between work and their respiratory symptoms. To do this, it is best to ask neutral questions, examples of which are given in Box 1. The duration of symptoms should be recorded as this will help identify the onset of the symptoms in relation to the onset of work exposures.

The latest evidence also supports the importance of enquiring about nasal symptoms in addition to asthma symptoms.8 Specifically, allergic rhinoconjunctivitis may start before the onset of OA, and the risk of OA is high in the 12 months following the onset of these symptoms.

Case update 1

When asked, your patient tells you that his symptoms, particularly wheeze, are better on days off work, and again he confirms that these are much better on holidays. He has noticed this effect with work ever since he moved to his current job two years ago.

Case commentary

This supports work-relatedness of his asthma, suggesting that further clinical and workplace assessment is needed as recommended by the OA Standard of Care, as either OA or WAA appear to be possible diagnoses. The fact that his symptoms were noted to be better on rest days as soon as he started work two years ago would support WAA, given that no symptom-free exposure period (the so-called latent period) was present. Early indicators suggest this may be asthma aggravated by the work environment. More information about his current work is now needed.

Occupational history

Talking with asthma patients about their job may help identify the cause of their asthma. An occupational history will help identify any inhaled exposures or work tasks that may be responsible for the work related-nature of the patient's asthma. Patients should be allowed to talk about their jobs freely, allowing you to list all previous jobs and job tasks. Time should be taken at least once to document likely current workplace exposures in more detail in the medical notes.

The recently updated Standard of Care for OA emphasises the central importance of taking an occupational history. The job title itself may be a useful guide to whether there are any exposures that might cause or aggravate asthma and, in addition, a list of reported exposures should also be made (e.g. flour, paints, cleaning agents).

Material Safety Data Sheets (MSDS) are required to be held by employers about hazardous agents used in the workplace and will form part of their risk assessment. Your patient should be able to supply you with useful information if you ask for a copy of these. Under the new Globally Harmonised System for classifying chemical health hazards, chemicals that can cause OA are classified as ‘H334’ and those that cause respiratory tract irritation are classified as ‘H335’. ‘R’-based risk categories were previously used, with R42 signifying potential to cause sensitisation by inhalation. In reality, information provided in the MSDS may only be of limited use in determining the exact nature of exposures in the workplace.

Table 2 lists the common jobs and agents associated with WAA and OA; it is intended as a useful working guide and not as an exhaustive list.

Case update 2

Your patient works day shifts as a warehouse worker for a large food company. This involves moving in and out of a cold storage facility, a large ‘walk-in room’ that is used as a chiller for keeping foodstuffs cool prior to their dispatch. He estimates that the temperature is kept at a constant 4°C and that the room adjoined to this is kept at a standard 19°C. All foodstuffs are fully packaged before they arrive at his department. He says he has been a little worried about discussing these symptoms at work because the company is looking to reduce staff numbers.

Case commentary

The occupational history suggests that the most likely exposure at work relates to changes in workplace temperature, and that this may well be responsible for the increased asthma symptoms. Table 2 highlights that temperature changes can affect asthma symptoms (given that the increased airway reactivity seen in asthma can cause airway narrowing on exposure to cold). Although the occupation of warehouseman is not represented in Table 2 , food processors are. You now suspect that the likely diagnosis is work-aggravated asthma.

Making the distinction between WAA and OA and giving advice

Whilst you are now reasonably confident that your patient has WAA, you should strongly consider, given the importance of this diagnosis, that your patient is referred for further advice. Previous studies have reported significant delays in making a diagnosis of OA and also that, once such a diagnosis is confirmed, the understanding and implications of this by patients are variable.10,11 The current Standard of Care for OA states that ‘health practitioners who suspect a worker of having OA should make an early referral to a physician with expertise in OA. All those involved in the potential identification of OA have an obligation to minimise delays’. The recent Primary Care Commissioning guide for asthma also recommends this approach.12

The benefits of such a referral include confirming the diagnosis and developing a patient-centred management plan, attempting to balance health and employment whenever possible. This may require providing advice for your patient in a number of important areas, particularly relating to altering work tasks or redeployment; adjusting asthma medications; accessing benefits (Industrial Injuries Disablement Benefit); and liaising with the worker's occupational health adviser, where present.

National referral centres are available, with access to the full range of diagnostic tests.13 If the patient has access to an occupational health service at work, then a useful first step would be to seek the patient's consent to discuss the work-relatedness of his/her asthma with the occupational health adviser.

Case update 3

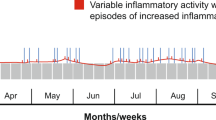

Your patient was seen at a specialist occupational asthma centre. An occupational respiratory specialist agreed with your assessment, and serial peak expiratory flow (PEF) values were requested and analysed using the OASYS 2 computer software. The patient was happy to perform these, but felt he was under more scrutiny at work from his managers when he was recording them. The PEF chart generated is shown in Figure 1. The PEF values are variable enough to support a diagnosis of asthma, but the work effect index (automatically calculated from the trace by the software) was equivocal. In addition, no definite allergen exposure could be identified.

Case commentary

This information will be key to the future management of this patient and again supports a diagnosis of WAA. The PEF readings support a diagnosis of asthma and some relationship between reduced readings and periods of work.

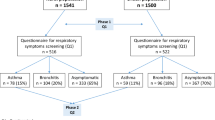

Occupational health perspective

Many doctors and nurses working in primary care may have extended roles as occupational health professionals or will be aware of the nature of such work. In part, the intent of occupational health is to ensure that risks to health are adequately identified and managed at work, as required by the Health and Safety at Work etc Act (1974) and the subsequent COSHH Regulations14 and the Workplace (Health, Safety and Welfare) Regulations 1992.15 There is evidence to support the fact that the prevention of asthma caused and aggravated by work can be achieved through appropriate risk assessment and control of relevant exposures. Periodic health surveillance may also be important, aimed at the early identification of workers with asthmatic symptoms made worse by work. This type of assessment would normally involve completing a brief respiratory questionnaire and measuring lung function periodically.

Workers should also have received appropriate health and safety training about potentially harmful exposures at work and should know what to do — and in particular to whom they should report — should they develop relevant symptoms, particularly if these occur between health surveillance visits.

Case update and summary

The specialist centre communicated with the occupational physician with the patient's written consent. The occupational physician, who was already aware that one of his workers had problems with asthma, confirmed that a recent risk assessment had been carried out and that no allergen exposure was identified. Workers, however, were under a regular surveillance programme as good practice and the potential for at least some to be exposed to allergens in food preparation. Following this communication, your suggested diagnosis of WAA was confirmed as being most likely.

The occupational physician subsequently recommended changes to your patient's work pattern and tasks, and his employer moved him to a standard temperature environment warehouse. A repeat OASYS-2 record following relocation showed an improvement, with a reduction in PEF variability and in the work effect index.

You reviewed him two months later and his asthma symptoms were much improved, and he reported using much less reliever inhaler at work.

Discussion

This case of WAA illustrates the importance of talking to asthma patients about their jobs and confirming whether their symptoms relate to the workplace. As in this case, if work-relatedness of asthma symptoms is confirmed, further occupational history helped to make a provisional diagnosis of WAA. Subsequent specialist referral and liaising with the occupational physician assisted confirmation of the initial diagnosis and excluded OA due to exposure to an allergen. In this case, the worker's employer was able to change his work tasks, which led to improved asthma control and a reduced frequency of inhaled medication.Footnote 1Footnote 2

Notes

Other sources of information

Asthma UK (http://www.asthma.org.uk/)

British Lung Foundation (http://www.lunguk.org/)

Health and Safety Executive (HSE) home page (http://www.hse.gov.uk/)

HSE asthma page (http://www.hse.gov.uk/asthma/index.htm)

British Thoracic Society website for asthma and occupational asthma guidance (http://www.brit-thoracic.org.uk/ and http://www.brit-thoracic.org.uk/guidelines.aspx)

OASYS Research Group, Midlands Thoracic Society, UK (http://www.occupationalasthma.com/)

References

Fishwick D, Barber CM, Bradshaw LM, et al.; British Thoracic Society Standards of Care Subcommittee Guidelines on Occupational Asthma. Standards of care for occupational asthma. Thorax 2008;63(3):240–50. http://dx.doi.org/10.1136/thx.2007.083444

Fishwick D, Barber CM, Bradshaw LM, et al. Standards of care for occupational asthma: an update. Thorax 2012;67(3):278–80. http://dx.doi.org/10.1136/thoraxjnl-2011-200755

British Occupational Health Research Foundation. Occupational asthma — identification, management and prevention: evidence based review and guidelines. 2010. http://www.bohrf.org.uk/downloads/OccupationalAsthmaEvidenceReview-Mar2010.pdf (accessed 23 Jan 2013).

Henneberger PK, Redlich CA, Callahan DB, et al; ATS Ad Hoc Committee on Work-Exacerbated Asthma. An official American Thoracic Society statement: work-exacerbated asthma. Am J Respir Crit Care Med 2011;184(3):368–78. http://dx.doi.org/10.1164/rccm.812011ST

Marabini A, Ward H, Kwan S, Kennedy S, Wexler-Morrison N, Chan-Yeung M . Clinical and socioeconomic features of subjects with red cedar asthma: a follow up study. Chest 1993;104:821–4. http://dx.doi.org/10.1378/chest.104.3.821

Ameille J, Pairon JC, Bayeux MC, et al. Consequences of occupational asthma on employment and financial status: a follow-up study. Eur Respir J 1997;10:55–8. http://dx.doi.org/10.1183/09031936.97.10010055

Cannon J, Cullinan P, Newman Taylor A . Consequences of occupational asthma. BMJ 1995;311:602–03. http://dx.doi.org/10.1136/bmj.311.7005.602

Gannon PFG, Weir DC, Robertson AS, Burge PS . Health employment and financial outcomes in workers with occupational asthma. Br J Ind Med 1993;104:321–4.

British Thoracic Society. British Thoracic Society/SIGN asthma guideline 2011. http://www.brit-thoracic.org.uk/Guidelines/Asthma-Guidelines.aspx (accessed 30 Oct 2012).

Fishwick D, Bradshaw L, Davies J, et al. Are we failing workers with symptoms suggestive of occupational asthma? Prim Care Respir J 2007;16(5):304–10. http://dx.doi.org/10.3132/pcrj.2007.00064

Poonai N, van Diepen S, Bharatha J, et al. Barriers to diagnosis of occupational asthma in Ontario. Can J Public Health 2005;96(3):230–3.

Primary Care Commissioning. Designing and commissioning services for adults with asthma: a good practice guide. 2012. http://www.pcc.nhs.uk/article/designing-and-commissioning-services-adults-asthma-good-practice-guide (accessed 30 Oct 2012).

Group of Occupational Respiratory Disease Specialists (GORDS). http://www.hsl.gov.uk/centres-of-excellence/centre-for-workplace-health/gords.aspx (last accessed 16 April 2013).

Health and Safety Executive. Control of Substances Hazardous to Health COSHH Essentials: Easy steps to control chemicals. Control of Substances Hazardous to Health Regulations (HSG193). 2003. http://www.hse.gov.uk/pubns/guidance/index.htm (last accessed 16 April 2013).

Health and Safety Executive. Workplace health, safety and welfare. Workplace (Health, Safety and Welfare) Regulations 1992. Approved code of practice. 1992.

Acknowledgements

Handling editor Jaime Correia de Sousa

The authors would like to acknowledge the input of the HSE Asthma Partnership Board for their assistance with the content of this case report. © Crown copyright 2013. Reproduced with the permission of the Controller of Her Majesty's Sationery.

Funding This publication was commissioned and funded by the Health and Safety Executive (HSE). Its contents, including any opinions and/or conclusions expressed, are those of the authors alone and do not necessarily reflect HSE policy.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

DF, CB, SW, and AS all contributed to the development of this article.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

The authors declare that they have no conflicts of interest in relation to this article.

Rights and permissions

About this article

Cite this article

Fishwick, D., Barber, C., Walker, S. et al. Asthma in the workplace: a case-based discussion and review of current evidence. Prim Care Respir J 22, 244–248 (2013). https://doi.org/10.4104/pcrj.2013.00038

Received:

Revised:

Accepted:

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.4104/pcrj.2013.00038