Abstract

Throughout the 20th century, the psychological literature has considered attention as being primarily directed at the outside world. More recent theories conceive attention as also operating on internal information, and mounting evidence suggests a single, shared attentional focus between external and internal information. Such sharing implies a cognitive architecture where attention needs to be continuously shifted between prioritizing either external or internal information, but the fundamental principles underlying this attentional balancing act are currently unknown. Here, we propose and evaluate one such principle in the shape of the Internal Dominance over External Attention (IDEA) hypothesis: Contrary to the traditional view of attention as being primarily externally oriented, IDEA asserts that attention is inherently biased toward internal information. We provide a theoretical account for why such an internal attention bias may have evolved and examine findings from a wide range of literatures speaking to the balancing of external versus internal attention, including research on working memory, attention switching, visual search, mind wandering, sustained attention, and meditation. We argue that major findings in these disparate research lines can be coherently understood under IDEA. Finally, we consider tentative neurocognitive mechanisms contributing to IDEA and examine the practical implications of more deliberate control over this bias in the context of psychopathology. It is hoped that this novel hypothesis motivates cross-talk between the reviewed research lines and future empirical studies directly examining the mechanisms that steer attention either inward or outward on a moment-by-moment basis.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

Attention is the prioritization of a small subset of externally available (external attention) or internally generated (internal attention) information, which is selected for further processing and allowed to drive action selection (for reviews, see Chun et al., 2011; Nobre & Kastner, 2014). Building on the premise—supported by much recent research (reviewed below)—that the processing of internal and external information relies on a single focus of attention, it follows that the focus of attention needs to be balanced or alternated between them. The principles underlying this balancing act have not been a topic of much active inquiry yet, however. We present here the Internal Dominance over External Attention (IDEA) hypothesis as one such principle, which states that attention is by default biased toward internally generated rather than externally available information. Even though the exact balance between external and internal attention is context dependent, this hypothesis captures the phenomenological given that, when we closely examine experience itself, we find that many contexts promote an internal focus of attention. This becomes easily apparent to anyone who has ever sat down to focus on ongoing somatic sensations during meditation, only to be continually distracted by internal thoughts, or to anyone experiencing a recent break-up and unable to stop painful thoughts from continually intruding in daily activities. Even outside the confines of meditation or major life events, we seem to often catch our minds wandering when we are in familiar contexts, such as during our commute, sitting at our desk, or just walking down the street. When nothing in particular is happening around us, we easily start daydreaming, suggesting a default internal state. These examples do not tell us in and of themselves about IDEA, but they do indicate that during a large proportion of our waking hours, attention appears to drift to internal activity—such as thinking, planning, remembering, etcetera—and away from the external environment (see Fig. 1).

The IDEA hypothesis in action. The IDEA hypothesis states that internally attended information is more intrusive, and thus a stronger determinant of behavior, than externally attended information. That is, when information in the external (i.e., perception) and internal (i.e., memory) environment is activated simultaneously, the latter more readily enters the focus of attention. For example, when we are attending a lecture, there may exist a competition between directing attention toward the information that is (externally) presented during a lecture or toward internally generated information, such as memories of a beautiful hiking trip in the mountains. The thickness of the upper arrow represents the bias or pull of attention toward the latter kind of information, despite the incentives to attend externally

However, there are naturally also contexts in which external information intrudes while attending internally. For example, when you are mentally rehearsing a shopping list and are suddenly interrupted by an acquaintance, your internal thread of thoughts is interrupted and attention reallocated externally. Our point here is not that the focus of attention is always directed toward internal information, but rather that the internal pull is inherently stronger and that therefore the focus of attention is more often allocated internally than externally. We assume this bias to be inherent to the operation of attention. As we examine further on in this paper, such an inherent bias can likely be attributed to the relatively stable and predictable environments in which our cognitive apparatus has evolved (see also Egner, 2014). Such predictability reduces the need for external processing and promotes the reliance on internal representations (such as prior knowledge), thus drawing attention inward, as also noted by scholars of memory (e.g., Tulving, 1983). Similarly, the highly influential predictive coding framework suggests that internal predictions are weighed or attended more strongly than bottom-up signals when navigating stable environments (e.g., Yon & Frith, 2021). Thus, even though there is copious evidence that the direction of attention can be dynamically modulated by context, we here contend that the human mind has evolved a default internal attention bias, explaining why IDEA is so commonplace in cognition.

In this article, this hypothesis is fleshed out in the light of the more recent progress in the study of internal attention (van Ede & Nobre, 2023, for a recent review). Our point here is more profound than just highlighting this exciting progress, however. We are addressing the question of the balance between external and internal attention as it usually operates and the primacy that internal information takes. To support the IDEA hypothesis, we review literatures on switching between external and internal attention, on intrusions between them (as studied, for example, in the visual search and working memory literatures), on mind wandering, and on meditation. As we maintain in this paper, a number of fundamental findings in these diverse literatures can be coherently understood in the light of IDEA. That being said, the evidence base is not fully mature at this time and lacks studies explicitly designed to test this proposal directly. Thus, the IDEA hypothesis is not a full-fledged theory of attention, but rather a provocative proposal meant to stimulate a critical reevaluation of conceptions of attention in the literature, which often view it as primarily externally oriented, and internal attention as derivative from external attention.

Finally, we believe this hypothesis provides a useful lens on some psychopathologies that can arguably be characterized by an imbalance in external and internal attention (see also Narhi-Martinez et al., 2023), including ruminative depression (e.g., Nolen-Hoeksema et al., 2008) and attention deficit hyperactivity disorder (e.g., Lanier et al., 2021). We examine how applying the IDEA hypothesis can help our understanding of these conditions. More specifically, we speculate on a potential mechanism underlying IDEA, and how it can be modulated when attentional selection has become dysfunctional.

In sum, guided by recent progress in the scientific literature on (internal) attention, we propose to redefine the relationship between external and internal attention in terms of IDEA. In the first part of this paper, we describe the IDEA hypothesis and its underlying rationale in greater detail. The second part provides a brief and selective review of research on attending external versus internal information, followed by an examination of the evidence for a single or alternating focus of attention between these two domains. In the third part, we review several strands of literature that provide empirical support for IDEA. As we hope that this hypothesis will introduce a new chapter in attention research aimed at collecting more relevant evidence on the balance between external and internal attention, we finish by describing key future directions and novel empirical tests of IDEA.

The Internal Dominance over External Attention (IDEA) hypothesis

At face value, the IDEA hypothesis might seem counterintuitive to many readers. We submit that this is due to two reasons. First, the vast majority of cognitive research and theorizing in the 20th century has considered attention almost exclusively as directed towards external stimuli (reviewed in Driver, 2001; Nobre & Kastner, 2014). However, it is likely that this focus was driven in large part by practical considerations, as the use of external stimuli makes experimental control of participants’ behavior more straightforward, rather than by the demands imposed by the topic under study itself. This (historically) one-sided use of external stimuli for attention research obscures just how commonly our attention is internally focused in everyday life. As a matter of fact, before the advent of systematic empirical research on (external) attention, attention was—more in line with subjective experience itself—conceptualized as internally focused (Mole, 2017). For example, Locke’s (1689) definition emphasized both the internal nature of attention and the subjective difficulty of escaping our “train of ideas”:

When the ideas that offer themselves (for, as I have observed in another place, whilst we are awake, there will always be a train of ideas succeeding one another in our minds) are taken notice of, and, as it were, registered in the memory, it is attention. (II, p. 19)

Second, even though we are often preoccupied with information that is internally generated (e.g., Killingsworth & Gilbert, 2010; but see Seli et al., 2018), we usually lack meta-awareness of the frequency and the amount of time we are preoccupied with internal representations of this nature (e.g., Schooler, 2002; Seli et al., 2013), which further biases our conception of attention toward its external application. This might seem contradictory with the previous point, but noticing the internal bias in attention in daily life requires keen observation of our conscious life. During times when we lack meta-awareness, we are often not actively controlling attention, allowing it to follow its biases undetected. Incidentally, the first example of internal bias we provided concerned meditation, which is a technique that can make us more aware of this internal absorption and, over time, can help us actually counter it (if that is considered desirable). We will return to this technique and its implications further on, but it is important to first consider the theoretical questions surrounding IDEA.

Arguably, there are two key theoretical questions that IDEA needs to address. The first one is why attention would be preferentially biased towards internal information. The second one is how the assumed bias for internally directed attention is instantiated in terms of cognitive and neural mechanisms. We posit that to reveal a detailed answer to the latter question should be an exciting, key goal of future studies of attention (see below). With respect to the former, we speculate that internal dominance of attention is due to the fact that human cognition has evolved (and is most commonly applied) in stable and predictable environments (see Egner, 2014), and is fundamentally predictive in nature (Clark, 2013). Evolutionary arguments have been successfully applied in understanding various aspects of cognition by assuming that the mind has been functionally organized through evolutionary pressures to generate adaptive behavior (e.g., Kurzban et al., 2013; see also Tooby & Cosmides, 1992). As noted by Kurzban and colleagues (2013), such an assumption does not entail that all behavior is adaptive or that the mind is optimally designed (e.g., environments change over time and some adaptations might not generalize to new ones), which applies to IDEA as well. This caveat aside, we take an evolutionary perspective here on Tulving’s (1983) proposal that, at any given moment, we are either in an encoding state or a retrieval state, and the balance between the two is a function of the volatility of the environment (for a review, see Honey et al., 2017; Tarder-Stoll et al., 2020). The encoding state corresponds to our construct of external attention, as here, information processing is biased toward (especially novel) external input, whereas in the retrieval state—corresponding to internal attention—processing is biased toward retrieving and manipulating information from long-term memory (see also Hasselmo & Schnell, 1994; Tulving, 1983, 2002).

Importantly, in a stable and predictable environment, people will primarily stay in a retrieval mode, as they can rely on internally stored information to guide actions. In a volatile environment, on the other hand, people will preferentially enter an encoding mode, promoting attention to, and learning of, potentially relevant new information. Thus, in the predictable context of our standard commute home, we can daydream or plan dinner (internal attention or retrieval mode) while driving, but when road construction shunts us on an unfamiliar detour, we need to truly pay attention to the road (external attention or encoding mode). We propose that navigating stable, familiar environments is (and has been) the norm for our species, and this has given rise to the dominance of internally over externally focused attention. The “familiarity” of the environment is a relative claim, but it is tangentially supported by a large body of research on perception. For instance, psychophysics studies have shown that humans are biased to expect current perceptual input to be highly auto-correlated with (or predicted by) perceptual input we received in the recent past (Cheadle et al., 2014; Cicchini et al., 2018; Fischer & Whitney, 2014; Gallagher & Benton, 2022). In other words, what we are currently seeing (in combination with efference copies of eye movement and other motor acts) reliably predicts our visual input in the next moment, due to a high level of spatiotemporal correlation in natural, time-varying images (Dong & Atick, 1995; see Pascucci et al., 2023, for a recent review). Moreover, this temporal predictability in itself aids in shielding internal attention against interference (e.g., Gresch et al., 2021).

Finally, there are more deliberate or goal-directed reasons for why internal attention has become the default state when the environment allows it. For instance, the unique human ability for detaching from the present moment and traveling through imagined scenarios is considered a great evolutionary strength (Bulley et al., 2016; Suddendorf & Corballis, 2007; Waytz et al., 2015). It has moreover been shown that mind wandering can have a beneficial impact in several ways (reviewed in Mooneyham & Schooler, 2013; Smallwood & Schooler, 2014), such as allowing for planning and preparation for the future (e.g., Oettingen & Schwörer, 2013), creativity (e.g., Baird et al., 2012; Ruby et al., 2013), finding meaning in one’s experiences (e.g., Waytz et al., 2015), and taking mental breaks (e.g., Baird et al., 2010).

In sum, there are experiential and theoretical arguments that speak in favor of IDEA. To reiterate, the IDEA hypothesis does not claim that attentional preferences for external or internal attention cannot be modulated by context; rather, we posit that there is a pervasive default bias for internal attention that can be overcome when the current context favors external processing, but the latter requires extra effort. Before discussing the empirical evidence in favor of the IDEA hypothesis, in the next section, we present, and provide evidence for, the core assumptions that underlie it.

Theoretical background

In this section, we outline the assumptions on which the IDEA hypothesis rests. We first examine selection for external and internal attention separately, after which we discuss evidence for the idea that external and internal attention share a single selection mechanism, which forces the focus of attention to alternate between them.

Selection from internal and external information

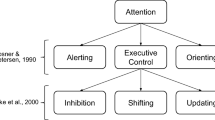

The empirical study of attention during the 20th century has mostly treated it as the selective prioritization of a subset of external stimuli, which has yielded much progress in our understanding of how attention operates in that domain (for reviews, see Driver, 2001; Nobre & Kastner, 2014; Lepsien & Nobre, 2006). External attention can be directed to a specific sensory modality (e.g., visual) and to different dimensions of the sensory input within each modality, such as spatial, temporal, feature, or object dimensions (reviewed in Chun et al, 2011). Sensory processing is facilitated for objects that are selected in the focus of attention (e.g., Carrasco et al., 2004; Posner & Petersen, 1990), resulting in faster and more accurate identification of attended stimuli (Jonides, 1980; Posner, 1980; Theeuwes, 1994; Wright & Ward, 2008; Yantis & Jonides, 1984). A typical demonstration of this attentional advantage can be found in the Posner precuing task (Posner, 1980). In this paradigm, after participants’ attention is (pre-)cued to a specific location on the screen, a target is presented to which a response needs to be made. The cue can be valid (i.e., directing attention to the same location as the target) or invalid (i.e., directing attention to the wrong location). Participants are faster and more accurate on valid trials than on trials with no or uninformative cues. Conversely, on invalid trials, participants are slower and more error prone, indicating that attention needs to be redirected from the cued location on these trials. Thus, a flexible (here, cue informed) external focus of attention selectively prioritizes behaviorally relevant information by amplifying its input (e.g., a spatial location). There are many ways of modeling the details of this perceptual prioritization, with perhaps the most influential one being the idea that attention biases the competition for selection or representation between different external stimuli by providing a relative gain in processing to the information that is relevant for behavior (Desimone & Duncan, 1995; Reynolds & Heeger, 2009).

Despite the historical focus on the processing of external stimuli in attention research, the notion that the selection, maintenance, and manipulation of internal information, or working memory (WM), is also an attentional process has found broader acceptance over the past 2 decades (Awh & Jonides, 2001; Chun et al., 2011; Cowan, 1999; Gazzaley & Nobre, 2012; Kiyonaga & Egner, 2013; Oberauer, 2002, 2019; Panichello & Buschman, 2021; Postle, 2006; van Ede & Nobre, 2023; Verschooren et al., 2019a, b). WM, more specifically, fulfills different attentional functions that underlie complex cognition in the absence of direct sensory input, ranging from the maintenance and manipulation of information to selective retrieval from long-term memory (Baddeley & Hitch, 1974; Cowan, 2017; Oberauer, 2002, 2009). In influential embedded-process models of WM, these functions are achieved through the activation (by attention) of the relevant internal representations (Cowan, 1999; Oberauer, 2002). We can tie this definition back to the examples we provided in the introductory section, which described cases in which such selection of internal information (e.g., paying attention to intrusive thoughts) takes precedence over external selection.

Empirical support for the claim that internal selection or prioritization is an attentional process has been obtained by using cues during a retention interval that direct the focus of attention to internal information (reviewed in Myers et al., 2017). These cues are used to refresh an item that was previously presented (Chun & Johnson, 2011), to select a subset of items that are held in working memory (Oberauer, 2002), or to probabilistically retro cue one out of several possible items during the retention interval (Griffin & Nobre, 2003; Landman et al., 2003). In these retro-cuing paradigms, in contrast to precueing paradigms (e.g., Posner, 1980), the (informative) cue is shown during the retention interval, after a set of visual stimuli has been removed from the display (reviewed in Myers et al., 2017; Souza & Oberauer, 2016). In other words, a retro cue directs attention towards an internal representation of a recently perceived stimulus. Similar to precueing, responses to the retro-cued item are faster and less error-prone than those to uncued items when probed. Consequently, retro cueing is a way to investigate how the (internal) focus of attention prioritizes a representation that is maintained in memory (Griffin & Nobre, 2003; Landman et al., 2003), which makes it more robust and easier to access for behavioral purposes (Myers et al., 2017).

It should be noted that there are differences in the nature of external versus internal selection, such as the ease of access to and items held in WM and the degree to which they are action oriented (see Myers et al., 2017; Souza & Oberauer, 2016; van Ede & Nobre, 2023, for discussions). However, as we show in the next section, these differences seem to relate mostly to certain representational features (e.g., whether they were previously individuated and processed to a relatively elaborate degree) and not to selection in the focus of attention itself (see also Panichello & Buschman, 2021; Zhou et al., 2022). For our purposes, the key point is that there is a shared attentional selection mechanism between them that can result in interference and competition. We discuss evidence for this overlap and competition in more detail in the next section (see further on in this paper for a discussion of cooperation between external and internal attention).

Overlapping selection mechanisms

Following the findings from retro cuing and related research, the view that selection of internal mental representations requires attention (see Cowan, 1999, for an early proponent) has become broadly accepted (Amir & Bernstein, 2021; Chun et al., 2011; Kiyonaga & Egner, 2013; Oberauer, 2019; Verschooren, Schindler, et al., 2019a, b). In their influential taxonomy of attention, Chun et al. (2011) have argued that attention is a property of multiple, different perceptual and cognitive operations. These authors suggested that attention can be split up into two distinct mechanisms based on the substrate it works on (i.e., stimuli in the external environment versus representations that are internally maintained). The question then arises whether there is one unitary attentional selection mechanism operating across external sensory input and internal mental representations or several, domain-specific ones. Whereas several authors have argued that there exist independent mechanisms for external and internal attentional selection (e.g., Bae & Luck, 2018; Baizer et al., 1991; Harrison & Bays, 2018; Hollingworth & Henderson, 2002; Mendoza-Halliday & Martinez-Trujillo, 2017; Tas et al., 2016; Woodman et al., 2001), others have championed the position that attention is unitary, sometimes directed externally and at other times directed internally (e.g., Awh & Jonides, 2001; Gazzaley & Nobre, 2012; Kiyonaga & Egner, 2013; Postle, 2006). We review the recent evidence in this debate next.

To begin with, even though some neuroimaging studies in humans suggest that brain areas involved in directing attention internally vs. externally are partly different (e.g., Hutchinson et al., 2009), many others have found overlapping activation for attending externally and internally, thus suggesting an overlapping mechanism (reviewed in Awh & Jonides, 2001; D’Esposito & Postle, 2015; Gazzaley & Nobre, 2012; Postle, 2006). For example, in an fMRI study, Nee and Jonides (2009) instructed participants to either filter out irrelevant perceptual or mnemonic information and found largely overlapping activation in the dorsolateral prefrontal cortex (dlPFC), frontal eye fields, premotor cortex, and superior parietal lobule for both conditions. These findings are in line with the attention-to-memory model, which proposes that the dorsal/ventral system distinction present in external attention also applies for attending to internal (mnemonic) representations (Cabeza et al., 2011; Ciaramelli et al., 2008; see also Asplund et al., 2010).

The most convincing evidence for a common neural selection mechanism for internal and external attention, however, has recently been obtained in both human and nonhuman primate studies using a decoding approach (Panichello & Buschman, 2021; Zhou et al., 2022). Zhou and colleagues (2022) obtained fMRI data while human subjects performed a probe-to-target matching task with both pre- and postcuing trials. In precuing trials, the fixation point cued the relevant color, after which three colored Gabor patches appeared. Following a (masked) delay, a Gabor probe appeared centrally and participants responded whether the orientation of the probe was tilted clockwise or counter-clockwise compared with the target orientation. In retro-cue trials, the three colored Gabor patches were first memorized, and, after a (masked) delay, the relevant orientation was color cued. Following this, a Gabor probe appeared, for which participants decided whether the orientation was titled clockwise or counterclockwise compared with the target orientation. Classifiers trained on patterns in visual, parietal, and (to some degree) frontal areas during (external) precuing predicted these patterns during (internal) postcuing, and vice versa. As decoding across conditions performed at 90% of the accuracy of decoding within conditions, the authors concluded that these patterns were nearly interchangeable. These results corroborate the existence of a single frontoparietal selection mechanism for both external and internal attention (see also Corbetta & Shulman, 2002; Cowan, 1999, 2019; Jerde et al., 2012).

Even more direct evidence for a single attentional selection mechanism was obtained using multi-unit cell recordings in nonhuman primates (Panichello & Buschman, 2021). Panichello and Buschman (2021) trained two monkeys to perform a pre- and a retro-cueing task while recording single-cell activity in several brain regions. On precueing trials, a spatial cue indicated which of two subsequently appearing colors needed to be reported (using a color wheel) after a memory interval. On retro-cueing trials, the cue indicating the location of the color that needed to be reported after the interval was presented after the two colors had been committed to WM. If there were a single selection mechanism for external and internal attention, it should be possible to use a classifier trained to decode the target location on external attention trials to accurately decode this location on internal attention trials, and vice versa. Panichello and Buschman (2021) indeed found that dlPFC neuronal responses generalized with above-chance decoding accuracy for external and internal trials. Similar to the findings reported by Zhou and colleagues (2022), this finding indicates that there exists a common selection mechanism for both external and internal attention.

Finally, when carefully considering the function of WM, a single focus for external and internal attention is sensible on theoretical grounds. We have seen earlier that the main mechanism for selecting information in the internal domain is thought to be WM, with information in the focus of attention being in the most activated state (Cowan, 1999; Oberauer, 2002). However, WM is not merely a mechanism for internal selection from long-term memory, but it sits at the interface between processing of the external and internal environments (Chun et al., 2011; Hollingworth & Luck, 2009; Narhi-Martinez et al., 2023; Verschooren et al., 2019b). Activation of WM contents through external input is in fact how WM is often operationalized in experimental tasks: Participants process an external stimulus and, following removal of that stimulus, maintain it in WM for the duration of the trial. In this situation, the information in the focus of attention is thus not retrieved from long-term memory, but initially activated via perceptual input. In line with the idea that the same focus of attention operates for external and internal input, Verschooren et al. (2021) have recently demonstrated that WM relies on a single (gating) mechanism to select from either external (perceptual) or internal (memory) sources. Taken together, the above findings converge on the idea of a single mechanism that can be activated by, and directed at, either external or internal input.

It is important to note here that the shared attentional selection assumed by the IDEA hypothesis does not imply identical mechanisms for the activation of objects in long-term memory and perception (which, at the neural level, is clearly not the case; see also Panichello & Buschman, 2021; Zhou et al., 2022). Rather, the key assumption, supported by the literature reviewed above, is that at a more central processing stage, only one source of information can be in the focus of attention (and driving behavior) at any one moment in time. This is the shared attention or attentional bottleneck that necessitates frequent switching between internal and external sources of information, and which we contend has a bias for internal sources. The IDEA hypothesis is therefore also compatible with nonunitary views of attention that nevertheless assume a central winner-takes-all mechanism. For example, a recent proposal of attention as a multilevel system of weights and balances that allow for mental prioritization argues that attention dynamically assign priority levels or weights to both externally and internally generated signals (Narhi-Martinez et al., 2023). The “winner” on each (local) level (i.e., the information with the highest weight) is then selected for a more global level where it competes with other information, and so forth, until the highest level of attentional selection. Crucially, such a view is still compatible with the IDEA hypothesis: Even though there may be several independent attentional mechanisms at different levels, the main point is that at the highest level of the processing or selection cascade, only one item can be selected, resulting in a necessary balancing act between external and internal attention.

To sum up, in the current section, we have argued that there is good evidence to suggest a single (likely prefrontal cortex mediated) focus of attention responsible for selecting both external and internal information. Since only a small set of either external or internal information can be attended at any one time, this leads to competition for attention between externally and internally activated representations. This raises the question of how the allocation of attention is balanced between them. In the following section, we review experimental evidence in support of the IDEA hypothesis. It is important to note that these findings were not originally interpreted in terms of imbalances between external and internal attention, and the focus of this research is not (explicitly) on an overall dominance of internal attention. Instead, we believe that IDEA provides an overarching perspective that can unify these disparate findings across a variety of different literatures in cognitive psychology.

Empirical support

In the previous sections, we have discussed key empirical findings on the relationship between external and internal attention that provide the foundational assumption for IDEA. We next examine relevant findings from several independent lines of research that provide empirical support for the core claim of the IDEA hypothesis—namely, that there is an inherent bias of attention towards internally driven information processing. We start by presenting recent findings on switch costs between external and internal attention, which suggest that shielding of attended stimuli from interference is more efficient for internal attention. We then review research on attention intrusions between the internal and external domains, as derived from the working memory, attention, and visual search literatures. We argue that, even though some of the evidence is still immature, the majority of it supports the hypothesis that internal-to-external intrusions are more potent and common than external-to-internal intrusions. This conclusion is echoed by a review of the mind wandering, sustained attention, and mental effort literatures, which provide strong evidence that even when participants are performing a purely externally oriented task, for a substantial proportion of the time they are nevertheless attending internally. Finally, we consider recent progress in research on meditation as an informative lens on how the balance between external and internal attention can be regulated explicitly.

Switching between external and internal attention

In the previous sections, we have mostly focused on the competition between external and internal information for attention. However, in most everyday situations, internally attended representations and externally geared attention cooperate (e.g., Stokes et al., 2012; Summerfield et al., 2006). Take as an example a visit to the grocery store with a memorized grocery list. This situation requires both external (scanning of the aisles) and internal (retrieving the items from the memorized list) attention. The single focus of attention discussed in the previous section entails that we cannot attend to both simultaneously but instead frequently switch our attention between external and internal sources of information (Barrouillet et al., 2011; Calzolari et al., 2022; Honey et al., 2017; Poskanzer & Aly, 2022; Servais et al., 2022; Tarder-Stoll et al., 2020; Verschooren et al., 2019b). Accordingly, after we have retrieved an item from our memorized grocery list, we switch attention externally to find this product among other products in the aisle. During the retrieval period, attention is drawn away from the products on the aisles. After the item is retrieved, it is maintained in WM, at the interface of internal and external attention, to guide the external search process (e.g., Stokes et al., 2012). However, despite the benefits of such cooperation (Summerfield et al., 2006), there are costs associated with switches between external and internal attention. In this section, we examine how these costs can inform us about the relationship between external and internal attention.

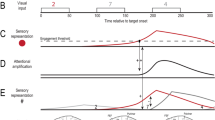

Verschooren, Liefooghe, and colleagues (2019) investigated such switches with a probe-to-target matching paradigm in which the targets were externally presented or internally retrieved on a trial-by-trial basis (see Fig. 2A). They found a cost for switching between external and internal attention: on switch trials (where an external trial is preceded by an internal one, or the other way around), participants were slower and more error prone than on repetition trials. Moreover, this cost was asymmetrical, being larger for switches towards internal compared with external attention (Fig. 2B).

Asymmetrical cost for switching between external and internal attention. A Example trial sequence. Before the start of the experiment, participants memorize a 2 × 2 array of internal stimuli and are familiarized with a 2 × 2 array of external stimuli in separate training sessions. On each trial, arrows point toward either the external targets presented on-screen or the internal ones in memory (represented by question marks), for external and internal trials, respectively. One of the targets, selected by a color cue, is compared with the centrally presented probe. The random trial transitions create four conditions of interest: external-repeat, external-switch, internal-repeat, and internal-switch. The (external and internal) switch costs can be calculated by subtracting the repeat trials from switch trials. B Representative results showing a larger internal (Int-Cost) than external (Ext-Cost) switch cost (see Hautekiet et al., 2022; Verschooren et al., 2019a, b, 2020)

This asymmetry might intuitively suggest that external attention is dominant, as it is harder to switch towards internal attention (see below), but empirical research on switching between dominant and non-dominant task sets has found that the opposite is true. Switch cost asymmetries are often observed under those conditions and they have played a central role in developing a theoretical understanding of how switching between different task sets may be regulated (Allport et al., 1994; Gilbert & Shallice, 2002; Mayr et al., 2014; Yeung & Monsell, 2003a, b). For example, Allport and colleagues (1994) used the Stroop task (Stroop, 1935), in which different color words are presented in different color fonts on each trial. People are a lot more practiced at word reading than color naming, so reading out the word it is the more dominant or prepotent response compared with naming the word’s ink color, resulting in robust congruency costs when participants are asked to name the color of a word, but the color and word activate competing responses (e.g., the word “red” printed in green). Allport and colleagues (1994) cued participants to either repeat or switch between color naming and word reading trials and observed typical switch costs, slower and less accurate responses on task switch than task repeat trials. Notably, this cost was larger when switching to word naming trials (i.e., from the less to the more dominant task set) than in the other direction.

Two opposing theories, priming (Allport et al., 1994; Gilbert & Shallice, 2002; Yeung & Monsell, 2003a, b) and associative interference (e.g., Mayr et al., 2014; Waszak et al., 2003), have been proposed to explain why it is more costly to switch towards the dominant task set (and to account for switch cost more generally, see Monsell, 2003; Vandierendonck et al., 2010, for reviews). Verschooren et al. (2020) pitted these accounts against each other in a series of experiments and found that associative interference provided a better explanation for the cost asymmetry for switching between external and internal attention (see also Hautekiet et al., 2022, for lack of evidence for an alternative account). This associative interference account is a learning account, insofar as it states that participants start associating the task stimuli and context with memory traces of external and internal attentional states when they carry out the task (see also Braem & Egner, 2018; Mayr et al., 2014). After this association has been formed, the task context automatically triggers the retrieval of the appropriate (most likely) attentional set (i.e., whether attention is primarily directed externally versus internally). On switch trials, the attentional set needs to be updated, which makes performance vulnerable to interference from the competing attentional set, resulting in a general switch cost. In line with this assumption, the switch cost asymmetry can be explained by differences in set shielding on repetition trials (see also the “Mechanism” section below for a detailed mechanistic interpretation). If performance is notably better on repetition than switch trials (that is, a large switch cost is incurred), it implies that the attentional set on these trials can be efficiently shielded. On the other hand, if there is only a small difference in performance between repetition and switch trials (a small switch cost), it implies that the attentional set cannot be shielded efficiently on these trials. When we apply this understanding to the cost asymmetry for switches between external and internal attention, it follows that an internal attentional set can be shielded more efficiently (reflected in a large switch cost) than an external attentional set (reflected in a small switch cost). In other words, this interpretation implies more stable internal than external attentional sets.

An alternative interpretation of these data might be that there are differences between external and internal attention in terms of difficulty that better explain the cost asymmetry than internal dominance. For instance, the reaction times and error rates are in general higher in the internal than the external condition (Hautekiet et al., 2022; Verschooren et al., 2019a, b; Verschooren et al., 2020). Several arguments can be put forward against a simple difficulty interpretation of the cost asymmetry, however. To begin with, Verschooren and colleagues (2020) compared the predictions from the associative interference (and priming) account with those of a memory retrieval account, which corresponds closely to a difficulty-based interpretation (i.e., an additional, effortful retrieval process is required for internal trials, especially when switching to internal), and they did not find evidence for this account. Relatedly, a recent study used degraded external stimuli to better match the external and internal trials in terms of difficulty, but the asymmetry remained (Hautekiet et al., 2022). Finally, even when participants were overtrained in the internal attention condition and responded faster to these trials than to external trials (Verschooren et al., 2019a, Exp. 1), the cost asymmetry was still present. As such, the available evidence clearly indicates that a difficulty account cannot fully explain the switch cost asymmetry, though future studies should systematically investigate whether it may nevertheless be a contributing factor.

Taken together, the larger cost for switching attention from external to internal sources of information can be attributed to the more stable maintenance of internal (than external) attentional sets on repetition trials. As this stable maintenance is, by definition, relaxed on switch trials, there is a larger difference between repetition and switch trials (and thus, a larger switch cost). For external attentional sets, stable maintenance on repetition trials is less effective, resulting in a smaller difference for repetition and switch trials (i.e., a smaller switch cost). More efficient internal than external shielding is a natural consequence of the default internal bias proposed by the IDEA hypothesis, which assumes that internal attention is indeed dominant. In the next section, we present several other findings that speak to such an internal shielding benefit.

Intrusions

Mine inner sense predominates in such a way over my five senses that I see things in this life—I do believe it—in a way different from other men. (Pessoa, 1966, pp. 13–14)

This quote by Fernando Pessoa (1888–1935), a philosopher and poet well known for his acute perception of how we experience the world, illustrates his intuition that internal information (pre)dominates external attention to the five senses. A key prediction of IDEA is indeed that there will be more intrusions from internally available information when processing external information than the other way around. More specifically, we reason that, if internal attention is dominant and can be more easily shielded (see the previous section), there should be less intrusions from irrelevant external information when actively engaging in this attentional state, than vice versa. This is a question that has not been directly assessed yet, but available evidence on both types of intrusions has recently been reviewed (Oberauer, 2019; see also Kiyonaga & Egner, 2013). We first review the evidence for internal-to-external intrusions, after which we turn our attention to external-to-internal ones.

When considering (unintended) intrusions from internal to external processing, interference studies and studies on WM guidance (i.e., internal attention) of external attention report strong and quasi-automatic impacts (for reviews, see Olivers et al., 2011; Soto et al., 2008). For instance, Soto and colleagues (2008) instructed participants to maintain a colored shape in memory for a delayed match-to-sample working memory test. Subsequently, during the delay interval, participants performed an unrelated visual search task but—crucially—the target or distracter stimuli of the search display can be shown in the color of the WM item. The key finding is that when the WM color coincides with the target color (“validly cued” trials) participants respond faster than on the baseline trials in which the memorized color was absent, whereas when the WM color coincides with a distracter (“invalidly cued” trials), participants respond slower than on baseline trials. Crucially, this interference occurs even in situations where it is predictably counterproductive, for instance in blocks where 100% of trials are invalid (Kiyonaga et al., 2012), which suggests a strong internal bias or automaticity. In a similar vein, it has been found that the paradigmatic Stroop effect can be induced when participants merely keep a color word in WM and are asked to respond to the color of a nonword stimulus (a colored rectangle) presented on screen during the WM retention interval (i.e., the WM Stroop effect; Kiyonaga & Egner, 2014; Pan et al., 2019; Vo et al., 2021; Wang, 2021). When the (internal) color word is congruent with the (external) stimulus color, responses are sped up and more accurate. Conversely, when they are incongruent, responses to the color of the external stimulus are slowed down and less accurate. These studies indicate that internal information can easily penetrate attention to the external environment even when this is not the goal of the agent.

With respect to external-to-internal intrusions, the evidence base is arguably more mixed (see also Lorenc et al., 2021). To begin with, there is some direct evidence for such intrusions from studies on time-based resource-sharing between internal and external attention (or “maintenance” versus “processing” demands; e.g., Barrouillet et al., 2004; Vergauwe et al., 2010). According to the time-based resource-sharing account, there is a domain-general, limited attentional resource that is shared between processing and maintenance of information, which results in a trade-off between them (in line with the literature reviewed above). The attentional resource is held to support both maintenance of (internal) information by refreshing its memory traces, which would otherwise decay, and the online processing of new (external) information. For example, Fougnie and Marois (2009) report that WM maintenance deteriorates when attention is directed to an external task during the WM delay. Moreover, this deterioration is a function of the duration of processing required by the external task (Barrouillet at al., 2011; Vergauwe et al., 2010; see also Woodman & Vecera, 2011). Similarly, in the WM Stroop study by Kiyonaga and Egner (2014), WM maintenance of the color word was deteriorated in incongruent trials, compared with congruent trials, suggesting that the perceptual categorization of the incongruent color interfered with maintaining the color word in WM. It has also been shown that salient but irrelevant external distractors disrupt control over the (visual) WM filter and thus can erroneously get encoded into WM (Dube & Golomb, 2021) and that such distractors can hurt long-term memory retrieval (Wais & Gazzaley, 2011; Wais et al., 2010). Finally, van Ede and colleagues (2020) provide direct evidence that internal selective attention is not only subject to goal-directed influences, but can also be driven by sensory-capture-like mechanisms (i.e., externally driven capture of internal attention; arguably the reverse equivalent of the internally guided capture of external attention discussed above). These findings provide proof-of-principle evidence that external-to-internal intrusions can occur, as one would expect given the single attentional focus between external and internal attention. However, the findings we discuss below indicate that such intrusions may be less common and less potent than internal-to-external ones, in line with the IDEA hypothesis.

Oberauer (2019) discusses two findings that further support the case that external content does not as readily intrude into internal attention. First, as we have discussed above, it has been found that the advantage provided by a retro cue does not suffer if an intervening task takes place that requires external attention, suggesting that retro cuing transforms internal representations to a format that is quite resistant to external interference (Hollingworth & Maxcey-Richard, 2013; Rerko et al., 2014; see Myers et al., 2017; Souza & Oberauer, 2016 for reviews). Second, the object-repetition benefit in WM (i.e., the finding that participants are faster in updating a mental object if the same mental object [compared with another one] needed to be updated in the previous trial) does not suffer if external attention needs to be directed to a stimulus in between two updating operations (Hedge et al., 2015). As a caveat, Oberauer (2019) cautions against interpreting these findings as evidence against external interference on internal attention, as the mechanism behind the retro-cuing and object-repetition benefits likely stems from binding the cued item or mental object to its context. After this binding process has been concluded, sustained internal attention is less necessary (Rerko et al., 2014). Lorenc et al. (2021) similarly emphasize that a unified account of WM’s resistance to external distraction needs to take into consideration the role and the degree of activation of the items in WM, and its relationship to the external task (see also Kim et al., 2005). For example, the findings discussed in this paragraph differ from the time-based resource-sharing studies, where interference was induced during the period where the binding takes place. Future research is required to disentangle this question.

In sum, there is evidence for the existence of both external and internal intrusions, but the impact of external distraction seems to be minimal for certain internal functional states. However, this is a tentative conclusion based on immature evidence, so further empirical testing is necessary. An informative within-study comparison of the magnitude of the interference effects from external to internal attention and the other way around has not been carried out yet. In the next section, we review the mind-wandering literature, which can be seen as a different kind of internal-to-external intrusion, in relation to IDEA.

Mind wandering

The studies examined in the previous section are diverse, but all of them have in common that external and/or internal intrusions are deliberately provoked by the experimental design. However, even when participants are not maintaining experimenter-induced (facilitative or interfering) information in memory, internal thoughts routinely disrupt performance of an external task. The role and impact of such intrusions are investigated in mind-wandering research (reviewed in Seli et al., 2016, 2018; Smallwood & Schooler, 2014). Mind wandering has been defined as a shift in the contents of thought away from an ongoing task and/or from events in the external environment to self-generated thoughts and feelings (Smallwood & Schooler, 2014), which we argue represents internally directed attention. Killingsworth and Gilbert (2010) found that, using an experience-sampling approach (“Are you thinking about something other than what you’re currently doing?”), participants’ minds wandered for roughly 50 percent of the sampled time. However, this might considerably underestimate the times during which participants are engaging in internal thoughts, for reasons discussed below.

To begin with, it is worth clarifying the relationship between mind wandering and internal attention. We embrace previous theoretical work on mind wandering that supposes three different attentional states, on-task, off-focus, and mind wandering, to capture task performance (Mittner et al., 2016). When participants are on-task, attention is focused on task-relevant inputs and responses. The off-focus state is a transient and (mostly) subconscious state of distraction in which the attentional focus is broadened, allowing for more explorative engagement with task-irrelevant information. Mind wandering occurs when this off-task state transitions into (focused, attentional) engagement with task-irrelevant, internally generated information (e.g., thinking about what to have for lunch later). The distinction between the off-focus and mind-wandering state clarifies that, even though an initial release of the focus of attention is required to arrive in a mind-wandering state (i.e., the off-focus state), this release is not equivalent to mind wandering itself. Rather, it is a (necessary) intermediate step between being on-task and mind wandering. The implication of this distinction is that actual mind wandering is not a passive process merely reflecting the absence of externally focused attention, but a cognitive state that involves internally directed attention. This point has been supported by findings showing executive control processes are involved in the coordination of the back-and-forth between mind-wandering and on-task states, but not for the off-focus state (Groot et al., 2022). As such, in light of the IDEA hypothesis, to the degree that mind wandering can be seen as a form of active internal attention, we assume it to be dominant over external attention, in the sense that it exerts a strong pull on attention (e.g., in the form of internal-to-external intrusions discussed here above).

At the empirical level, given that mind wandering itself is defined as self-generated mental content, it is not straightforward to manipulate this phenomenon experimentally (see Kane et al., 2007; Levinson et al., 2012). To estimate the frequency of participants’ mind wandering, researchers have employed several different indices (reviewed in Smallwood & Schooler 2014). The most widely used index is the probe-caught method (Smallwood & Schooler, 2006), where participants perform some form of (external) continuous performance task and are occasionally probed on whether they were focused on the task at hand or not. A benchmark finding is that participants have worse task performance during episodes of mind wandering compared with periods of on-task focus (Smallwood & Schooler, 2014; see also deBettencourt et al., 2019).

Of relevance for our purposes, some researchers have included probes that ask not just about mind wandering itself, but also other kinds of distraction from internal and external sources. This allows us to compare the relative proportion of time participants are distracted by these different types of (deliberate or spontaneous) intrusions. For example, Unsworth and Robison (2018) used a probe with six different response options and provided the proportion with which each response was selected (see also Robison et al., 2017; Stawarczyk et al., 2011; Unsworth & Robison, 2016; Ward & Wegner, 2013). Apart from mind wandering (both spontaneously and deliberately), the response options also included the occurrence of external distraction (e.g., sounds or sensations), task-related interference (i.e., thoughts about the task at hand, such as whether one is performing well), and mind blanking (i.e., thinking of nothing). These probes were presented during three different cognitive tasks at random intervals. Averaged over the three tasks, participants reported being on task 44% of the time, 29% task-related interference, 3% external distraction, 12% spontaneous and 3% deliberate mind wandering, and 9% mind blanking.

A comparison is often made between the proportion of time participants direct their attention on task (here, 44%) versus the proportion of time they spend mind wandering (here, 15%). This is interpreted as a comparison between external attention (on task) and internal distraction (mind wandering). However, mind-wandering probes are rarely used with tasks requiring internal attention, which makes it hard to conclude something concerning IDEA, for which this comparison would be necessary (e.g., are there more external intrusions during internal tasks than the other way around?). That is, within our framework, we are mostly interested in the amount of time internal attention interferes with external attention, and vice versa. This question can nonetheless be answered in this context if we compare the amount of mind wandering (interference from an internal source) to external distraction (interference from an external source). This comparison reveals that participants experience substantially more of the former (15% versus 3%). Moreover, IDEA is about internal attention in general and therefore encompasses task-related interference as well, which are internal thoughts about task performance that draw attention away from the task. If we add this type of distraction to self-reported mind wandering, we end up with 44% distraction from internal sources compared with 3% from external sources, which is strongly in line with the IDEA hypothesis. A similar analysis can be applied to a study by Stawarczyk and colleagues (2011). Even though they reported higher levels of distraction from external sources (around 20%), mind wandering and task-related internal thoughts together accounted for a far larger proportion of distraction (52%).

Moreover, considering that these numbers stem from a time when people are actively engaged in an instructed, external attention task, they are likely low-ball estimates of mind wandering in everyday life when the focus of attention is typically less constrained. Accordingly, it has been found that mind wandering occurs more frequently in nondemanding environments (Kane et al., 2007; Levinson et al. 2012). In the context of the IDEA hypothesis, this can be linked to the notion that in stable and predictable environments, we enter a retrieval mode, biasing attention more internally. Another reason that the above estimates are likely lower bounds on the time normally spent orienting attention internally is that the very use of regular mind-wandering probes tends to draw participants back to the externally oriented task (see also Schooler, 2002; Seli et al., 2013). Without these probes, the frequency and duration of mind wandering would likely be considerably longer. Relatedly, Seli and colleagues (2018) found that the frequency of mind wandering varied when allowing for graded responses from 10% (completely off task) to 60% (somewhat off task). More conceptual work is required on what exactly constitutes mind wandering, for which the IDEA hypothesis can help, as we argue further on.

Apart from these basic findings from the probe-caught method, researchers have been interested in the relationship between mind wandering and meta-awareness (Schooler, 2002), the explicit awareness of the current content of one’s thoughts (Smallwood & Schooler, 2014). It has been found that participants often lack this type of awareness when mind wandering, and that the impact of mind wandering is more pronounced when meta-awareness is absent (Schooler, 2002; Smallwood et al., 2007; but see Seli et al., 2013). Moreover, when participants need to report, without the help of probes, when they are mind wandering (i.e., when using the self-caught method), a relationship between mind wandering and task performance is often not observed (Schooler et al., 2004). Such a relationship is often found, however, with objective measures of mind wandering such as pupillometry (e.g., Smallwood et al., 2011), suggesting that the self-caught method does not accurately capture the frequency with which people’s minds are wandering due to a lack of awareness: we are frequently mind wandering without awareness. In sum, even though attention is often drawn inwardly, we are not always aware that this is happening, especially when we are not being probed about it. An intriguing possibility is that the IDEA hypothesis has not been explicitly recognized before because of this lack of meta-awareness.

Finally, research closely related to mind wandering, on sustained attention and mental effort, provides further support for—and insight into—the IDEA hypothesis. This research is conceptually similar to mind wandering but takes the (effort related to) time one spends on a task as the primary variable of interest. A particularly relevant model in the context of IDEA is the resource-control theory (Thomson et al., 2015), which was developed in the context of sustained attention and is able to account for commonly observed time-on-task effects (i.e., decreased performance over time; see Esterman & Rothlein, 2019; Fortenbaugh et al., 2017, for reviews). Much like IDEA, this model explicitly conceptualizes mind wandering as the default state of our cognitive system and assumes we rely on effortful cognitive control to counter this ever-present bias for attention to gravitate toward internal thought. Moreover, it is supported by empirical research on vigilance tasks, which are often deemed effortful by participants (Boksem et al., 2005, 2006; Lorist et al., 2005; Müller & Apps, 2019).

More broadly, we can also link these ideas to research on mental effort, which has suggested that our resources for exerting cognitive control (e.g., in overcoming attention biases) are limited (see Shenhav et al., 2017, for a review) and that exerting mental effort is experienced as aversive (Vermeylen et al., 2019, 2020). An influential idea explaining these feelings of effort and aversion, the opportunity cost model (Kurzban et al., 2013), proposes that the more one stays on task, the more one incurs opportunity costs, and the higher the probability of engaging in mind wandering. Specifically, this model explains why controlled states are costly (put differently, why default states are preferred) by positing the subjective cost of cognitive control can be quantified by the relationship between the subjective value of the mental activity currently engaged in compared with the subjective value of all other possible mental activities, including mind wandering (see also Esterman & Rothlein, 2019; Fortenbaugh et al., 2017).

In sum, findings from a substantial literature on mind wandering are largely in accord with the IDEA hypothesis. In the next section, we discuss a research field that is usually not considered in basic attention research (i.e., meditation), but, as we will explain, this practice is very informative to IDEA as well.

Meditation

The idea that our attention is drawn more to internal content than to our immediate environment might go against our intuition, especially as trained cognitive scientists. However, this insight is central to meditation practice, a millennia-old discipline specifically dedicated to figuring out how the internal pull on attention may be overcome, so that we can stay aware and attentive in the present moment (Laukkonen & Slagter, 2021, for a recent review). That is, not unlike the mind-wandering and sustained-attention literature reviewed here, above, the practice of meditation reveals how hard it is to keep internal thoughts from intruding, which again is in line with a pervasive internal bias (e.g., Jain et al., 2007; Lutz et al., 2008). As we have seen in the previous section, such an internal pull that draws attention away from external information is a form of internal attention. Moreover, from the research presented in the previous section, we know that participants often lack (meta-)awareness during mind wandering, which suggests that attention is directed internally by default in its absence. Research on (mindfulness) meditation speaks directly to this point, and has some links to the IDEA hypothesis as well, and we therefore discuss this literature here.

There are many different forms of meditation (Davidson & Kaszniak, 2015; Van Dam et al., 2018), but the best-studied techniques from an empirical perspective are focused attention and open monitoring (Josipovic, 2010; Laukkonen & Slagter, 2021; Lutz et al., 2008, 2015). These techniques represent successive stages of progress in meditation, but with respect to the IDEA hypothesis we can generalize across them (see Laukkonen & Slagter, 2021, for a more detailed analysis). The practice of these types of meditation consists of focusing attention on a single object, most often a somatosensory sensation such as the breath, or just openly monitoring whatever sensation, thought, or emotion arises (Goldstein, 2013; Laukkonen & Slagter, 2021). Repeated practice is expected to promote the meta-awareness of intrusive thoughts that is often lacking during episodes of mind wandering (see also Barinaga, 2003). It has indeed been found that meditation reduces mind wandering (Levinson et al., 2014; MacLean et al., 2010; Mrazek et al., 2012) and promotes sustained attention (Lutz et al., 2008), executive control (Jha et al., 2007), and self-regulation (Brown & Ryan, 2003; Chambers et al., 2008). Moreover, focusing on the direct experience of sensations from the body should prevent elaborative, ruminative processing, which would otherwise draw attention inwardly (Bishop et al., 2004; see also Teasdale et al., 1995). This is supported by a study from Slagter and colleagues (2007), which found that meditators were better at detecting the second target in an attentional blink paradigm. This finding was interpreted as resulting from decreased elaborative processing of the first target, which freed up attention for detection of the second target.

Moreover, meditation has recently been conceptualized within a predictive coding account of the mind (Laukkonen & Slagter, 2021; see also Lutz et al., 2019; Pagnoni, 2019), which further emphasizes the commonalities between certain assumptions of meditation and the IDEA hypothesis. A central aspect of the predictive processing account is that the internal model of the world is hierarchical, with predictions ranging from the concrete (e.g., sensorimotor and interoceptive sensations) to the abstract (e.g., internal thoughts; Friston & Stephan, 2007). It is these abstract predictions that allow us to break free from the current embodied context and make space for counterfactual thinking or mind wandering (Friston, 2018; Metzinger, 2017). Laukkonen and Slagter (2021) propose that meditation operates by deconstructing the internal model and countering our habit of forming predictions about stimuli and thoughts. This is in line with the IDEA hypothesis, which entails that in the absence of a strong internal model, an encoding mode, reflecting a bias to processing (especially novel) external input, becomes easier to maintain.

In sum, the meditation tradition shares with the IDEA hypothesis the notion that our minds are by nature absorbed in internal thoughts and adds the insight that meta-awareness can remedy the imbalance between external and internal attention. More specifically, the literature reviewed above indicates that when we are not mindful of where attention is directed (i.e., not being meta-aware), it follows its natural bias toward internal sources of information. Meditation practice is assumed to overcome this lack of meta-awareness and the associated internal bias by training practitioners to keep their attention in the experience of the present, and this is largely backed up by findings from empirical research. Rephrased into IDEA, this means that (mindfulness) meditation is about practicing to remain in an encoding mode, even though the meditation environment is typically stable enough to let the mind wander in retrieval mode. To be clear, this is not to imply that an encoding mode is intrinsically preferrable to a retrieval mode. Rather, given the existing internal bias, practicing the maintenance of an encoding mode may allow us more deliberate control in exploiting the advantages of each. We discuss in the practical implications section why and when this might be important.

Future directions and implications

In this paper, we have proposed a new perspective on the relationship between external and internal attention. More specifically, we formulated the IDEA hypothesis, which states that a shared focus of attention is biased towards internal sources of information, and reviewed several strands of literature in its favor. The foremost implication of the IDEA hypothesis is a recognition that our conscious life is mostly internally oriented, especially in stable contexts, even if we are not consistently aware of it. We hope that this insight can help bring about a shift in focus of research to a more ecologically valid understanding of attention, and cognition more broadly. In what follows, we briefly sketch out what this might mean at the theoretical and applied levels.

Mechanism

When we introduced the IDEA hypothesis, we argued that there are two key theoretical points that need resolving. The first one (i.e., why attention would be biased internally in the first place) we have already addressed by referring to the stable and predictable environments in which human cognition has evolved and usually takes place. In these types of environments, we can rely on our internal models and free up resources for further processing of internal information, which consolidates the internal bias. The second one concerns the exact manner in which IDEA is implemented, which is still an open question. The IDEA hypothesis primarily reflects a phenomenon or outcome and, as such, it might be sustained by several mechanisms. However, even though IDEA is likely multiply determined, it is nevertheless stimulating for future research to provide some specific conjecture on a plausible mechanistic implementation.

As we examined above, the associative interference interpretation of the switch cost asymmetry in part inspired the formulation of the IDEA hypothesis (Verschooren et al., 2019a, b, 2020). It is therefore worth examining this account in more detail here to see whether it can be applied more broadly than just switching contexts. Associative interference assumes that memory traces of attentional top-down settings are automatically encoded with and bound to a stimulus one is interacting with (e.g., Waszak et al., 2003; for reviews, see Monsell, 2003; Vandierendonck et al., 2010). If the same stimulus or task context is encountered again later on, it serves as a retrieval cue for these attentional top-down settings (Logan, 1988), which include the abstract control setting involved in responding to the stimulus (for reviews, see Abrahamse et al., 2016; Braem & Egner, 2018; Chiu & Egner, 2019; Egner, 2014). In a task switching context, this implies that competing attentional top-down settings are activated on each trial. The impact of the competing setting is more detrimental on switch than on repeat trials, however, as a WM update has to take place when switching from one attentional set to the other, rendering the settings more susceptible to interference (Dreisbach & Haider, 2008, 2009; Dreisbach & Wenke, 2011).

A mechanistic explanation for this vulnerability on switch trials comes from the prefrontal basal ganglia working memory model (PBWM), which assumes a basal ganglia input-gating mechanism protects current contents in WM from internal (e.g., competing attentional top-down settings) and external (e.g., distracting stimuli) interference (Frank et al., 2001; Hazy et al., 2006). That is, when the gate is closed (i.e., on repetition trials), the current content is maintained, but when it is opened (i.e., on switch trials), new information can enter WM. As the gate is opened on switch trials, the competing attentional set can exert more influence on performance (Mayr et al., 2014). This specific application of the PBWM applies mainly to task-switching contexts, but it is reasonable to assume that, if gating is more efficient for internal attention in those contexts, it will be more efficient in other contexts as well. As such, this mechanism might apply to internal intrusions and shielding more broadly. Indeed, the PBWM mechanism has been applied to gating of external and internal information in general, but past research has mostly focused on the overlap between them (Verschooren et al., 2021). Future research into potential differences between gating for external and internal attention could provide a mechanism underlying IDEA.

Alternatively, IDEA can be integrated with research on encoding and retrieval states (e.g., Tulving, 1983), which we have equated with external and internal attention, respectively. At the mechanistic level, the retrieval mode is assumed to operate through recurrent, auto-associative connections in the memory systems of the brain, such as the CA3 subfield of the hippocampus (Aly & Turk-Browne, 2017, 2018). These recurrent connections are a good candidate mechanism for the bias toward internally oriented processing, as they need to be overcome through neuromodulation (e.g., from acetylcholine) when the system requires a switch to an encoding state (Poskanzer & Aly, 2022; Ruiz et al., 2021; Tarder-Stoll et al., 2020). This additional step away from the default mode of the system (i.e., recurrent, auto-associative connections) is strongly compatible with the IDEA hypothesis, which would indeed assume that internal attention is the default state.

To sum up, we have examined two potential mechanisms underlying IDEA. It could be that the PBWM gating mechanism is less efficient for external sources of information, or that recurrent connections in hippocampus need to be overcome to activate an encoding mode. These are however speculative explanations that require further theoretical and empirical elaboration and perhaps integration. For example, at the empirical level, new experimental procedures need to be developed that can directly compare intrusions from external-to-internal attention, and vice versa. At the theoretical level, one import step moving forward will be to formalize the IDEA hypothesis quantitatively and investigate its subcomponents using a computational modeling approach (see also Trutti et al., 2021; van Rooij, 2022).

Practical implications

With a kind of effort he began almost unconsciously, from some inner craving, to stare at all the objects in front of him, as though looking for something to distract his attention; but he did not succeed, and kept dropping every moment into brooding. (Dostoeysky, 1866, p. 73 )

In the introduction of this paper, we included a quote by Locke (1689) which emphasized how difficult it can be to escape our train of thought. In this last section, we include the quote above from Crime and Punishment (1866), in which Dostoevsky’s dissects in minute detail how excessive rumination affects our mental and physical health. As we examine in this section, there is much evidence for a relationship between an excessive internal focus and psychopathology (see also Narhi-Martinez et al., 2023). The IDEA hypothesis provides an overarching framework for this internal bias as the default state, which is a better starting point than the status quo for understanding how it becomes dysfunctional sometimes.

We have indeed seen that there are good reasons for (and benefits of) an internal attention bias, but there can be downsides to it as well. First, being distracted by thoughts often has a detrimental influence on ongoing task performance (as, for example, demonstrated in the mind-wandering literature). Moreover, it seems that for most people, too strong an internal bias can have a negative impact on their quality of life (e.g., Killingsworth & Gilbert, 2010). This is a well-documented finding in research on depression and rumination (Keller et al., 2019; Nolen-Hoeksema et al., 2008; Watkins & Brown, 2002), which are characterized by an excessive internal focus on negative thoughts. Thus, while a moderate level of internal reflection and meta-cognition may be a core component of a life well-lived, an excessive internal focus can lead to psychopathology. This inference is further supported by a substantial literature on the relationship between mood and the balance of external and internal attention (reviewed in Vanlessen et al., 2016). Vanlessen and colleagues (2016) synthesized a broad range of these findings and proposed that whereas positive mood tips attention externally, negative mood tips it internally. Taken together, these research lines suggest that there are bidirectional interactions between the balance of attention, mood, and psychopathology.

Similarly, imbalances between external and internal attention are assumed to underlie ADHD, potentially producing the signature symptoms of inattention and distractibility (Lanier et al., 2021). We have highlighted above, based on work by Aly and colleagues (Aly & Turk-Browne, 2017, 2018; Ruiz et al., 2021; Tarder-Stoll et al., 2020), that the hippocampus may function as an important hub in the balancing of external and internal attention. In people with ADHD symptoms, hippocampal function is deregulated (Plessen et al., 2006), which could underlie the reduced control over attentional balance. Moreover, ADHD shows strong co-morbidity with post-traumatic stress disorder (PTSD; Antshel et al., 2013). PTSD has the spontaneous retrieval of unwanted thoughts and memories as one of its defining symptoms, which is also common in rumination and depression (Keller et al., 2019; Nolen-Hoeksema et al., 2008). These lines of research in different pathologies point towards switches between external and internal attention, and excessive internal biases, as being central to pathogenesis and symptomatology.