Published online Jan 28, 2013. doi: 10.3748/wjg.v19.i4.528

Revised: August 6, 2012

Accepted: November 6, 2012

Published online: January 28, 2013

AIM: To investigate whether endoscopic submucosal dissection (ESD) can be safely performed at small clinics, such as the Shirakawa Clinic.

METHODS: One thousand forty-seven ESDs to treat gastrointestinal tumors were performed at the Shirakawa Clinic from April 2006 to March 2011. The efficacy, technical feasibility and associated complications of the procedures were assessed. The ESD procedures were performed by five endoscopists. Sedation was induced with propofol for esophagogastorduodenal ESD.

RESULTS: One thousand forty-seven ESDs were performed to treat 64 patients with esophageal cancer (E), 850 patients with gastric tumors (G: 764 patients with cancer, 82 patients with adenomas and four others), four patients with duodenal cancer (D) and 129 patients with colorectal tumors (C: 94 patients with cancer, 21 patients with adenomas and 14 others). The en bloc resection rate was 94.3% (E: 96.9%, G: 95.8%, D: 100%, C: 79.8%). The median operation time was 46 min (range: 4-360 min) and the mean size of the resected specimens was 18 mm (range: 2-150 mm). No mortal complications were observed in association with the ESD procedures. Perforation occurred in 12 cases (1.1%, E: 1 case, G: 9 cases, D: 1 case, C: 1 case) and postoperative bleeding occurred in 53 cases (5.1%, G: 51 cases, D: 1 case, C: 1 case); however, no case required either emergency surgery or blood transfusion. All of the perforations and postperative bleedings were resolved by endoscopic clipping or hemostasis. The other problematic complication observed was pneumonia, which was treated with conservative therapy.

CONCLUSION: ESD can be safely performed in a clinic with established therapeutic methods and medical services to address potential complications.

- Citation: Sohara N, Hagiwara S, Arai R, Iizuka H, Onozato Y, Kakizaki S. Can endoscopic submucosal dissection be safely performed in a smaller specialized clinic? World J Gastroenterol 2013; 19(4): 528-535

- URL: https://www.wjgnet.com/1007-9327/full/v19/i4/528.htm

- DOI: https://dx.doi.org/10.3748/wjg.v19.i4.528

One-piece resection is considered the gold standard for endoscopic mucosal resection (EMR) because it provides an accurate histological assessment and reduces the risk of recurrence[1-5]. However, it is difficult to resect large and ulcerative lesions en bloc using conventional EMR techniques. Therefore, a new technique, endoscopic submucosal dissection (ESD), has been developed[6-8]. ESD is a minimally invasive treatment for gastrointestinal cancer. It is usually performed in general hospitals because of the high frequency of complications and the need for a high level of technical skill[9-12]. The occurrence of complications negatively affects the quality life of patients and sometimes requires surgical treatment. Bleeding is one of the most common complications of ESD[13]. The use of hemostatic devices or endoscopic clipping prevents the occurrence of bleeding after ESD procedures[13]. Therefore, cases that require surgical treatment for bleeding after therapeutic procedures are quite rare. Perforation is also one of the most common complications of ESD[13]. Surgical treatment for iatrogenic perforation should be avoided at local clinics because most of these clinics do not have appropriate equipment for such surgeries.

The Shirakawa Clinic, a 19 bed inpatient clinic, was founded as a special clinic for endoscopic surgery. The main procedures performed at this clinic include endoscopy and endoscopic treatments. This clinic does not have surgeons or appropriate equipment for surgery. When surgical treatment is required, patients are transferred to a related tertiary hospital.

This study investigated whether ESD can be safely performed at small clinics such as the Shirakawa Clinic. The efficacy, technical feasibility and associated complications of ESD were assessed in the Shirakawa Clinic.

We reviewed all cases of endoscopy and ESD to treat gastrointestinal tumors performed at the Shirakawa Clinic from April 2006 to March 2011. ESD was performed not only for treatment purposes, but also to make accurate histological diagnoses. Indications for ESD primarily included mucosal types of gastrointestinal cancers, excepting poorly differentiated cancers. A detailed description of the indications has been previously reported[9-12]. Depending on the procedure, we followed the guidelines of either the Japan Esophageal Society[14], the Japanese Gastric Cancer Association[15] or the Japanese Society for Cancer of the Colon and Rectum[16].

The Shirakawa Clinic includes 19 inpatient beds, 5 endoscopists and 5 endoscopical technicians certified by the Japan Gastroenterological Endoscopy Society. The endoscopic treatment room and treatment procedures are shown in Figure 1. The treatment teams included two doctors (one operator and one doctor who administered propofol sedation), two nurses and two endoscopical technicians. The years of experience of the endoscopists who performed the endoscopic treatment, including EMR, were as follows: 24 (Onozato Y), 20 (Sohara N), 16 (Hagiwara S), 14 (Iizuka H), and 11 (Arai R) years. The number of years of experience with ESD treatment were 10 (Onozato Y), 5 (Sohara N), 4 (Hagiwara S), 8 (Iizuka H), and 2 (Arai R) years. The numbers of ESD treatments performed were about 1000 (Onozato Y), 250 (Sohara N), 150 (Hagiwara S), 300 (Iizuka H), and 50 (Arai R) cases, respectively. All ESD procedures were supervised by Onozato Y, who had most experience performing ESD among the five endoscopists. As a result, all ESD cases were similarly treated because of the careful supervision.

The intravenous administration of pethidine hydrochloride and propofol was used for sedation, except in colorectal ESDs. The tumors were treated using standard ESD procedures as previously described[9-12]. For each patient, a data collection sheet was used to obtain relevant clinical information about the patient, tumor, procedure and complications. The data sheets were reviewed retrospectively. Findings from abdominal X-P, physical examinations and blood tests were assessed using a clinical pathway as a basis. Patients without complications were permitted to eat soft foods two days after ESD and then were discharged after endoscopic follow-up on the seventh day. The efficacy and complications of ESD were assessed.

One-piece resection was defined as en bloc resection. The resections were considered to be curative when tumor-free vertical and horizontal margins were achieved, en bloc resection was performed and resection criteria were met[14-16]. The operation time was calculated from the data of digital versatile disc recording systems for endoscopic procedures. Time from the start of the mucosal incision to the completion of the dissection was defined as the operation time. The time for marking or hemostasis after dissection was excluded from the operation time.

Procedure-related bleeding was subdivided into intra- and postoperative groups. Intraoperative bleeding was defined as large amounts of bleeding during the procedure and difficult cases of hemostasis. Postoperative bleeding was defined as clinical evidence of bleeding as evidenced by hematemesis or melena at 0-30 d after ESD and requiring endoscopic treatment. Furthermore, postoperative bleeding was subdivided into early postoperative (within three days of ESD) and delayed postoperative (more than three days after ESD) groups. We also recorded the incidence of perforation during endoscopy and after the procedures based on clinical evidence.

Endoscopic follow-up examinations were performed routinely one week, three months, nine months and every six months after ESD. To exclude distant metastases, abdominal ultrasonography (and/or computed tomography) was performed before ESD and three months and every six months after ESD on the same day as endoscopy.

The continuous variables are presented as the mean ± SD. The data were analyzed using the Fisher’s exact probability test, and Mann-Whitney’s U-test. A P value < 0.05 was considered to be significant.

From April 2006 to March 2011, a total of 35 540 endoscopies were performed at the Shirakawa Clinic. A total of 1047 lesions in 873 patients were resected with ESD (Table 1). Sixty-four patients with esophageal cancer (E), 850 patients with gastric tumors (G: 764 patients with cancer, 82 patients with adenomas and four others), four patients with duodenal cancer (D) and 129 patients with colorectal tumors (C: 94 patients with cancer, 21 patients with adenomas and 14 others) were treated. The en bloc resection rate was 94.3% (E: 96.9%, G: 95.8%, D: 100%, C: 79.8%). The median operation time was 46 min (range: 4-360 min) and the mean size of the resected specimens was 18 mm (range: 2-150 mm). No mortal complications were observed in association with the ESD procedures. Perforation occurred in 12 cases (1.1%, E: 1 case, G: 9 cases, D: 1 case, C: 1 case) and postoperative bleeding occurred in 53 cases (5.1%, G: 51 cases, D: 1 case, C: 1 case); however, no cases required emergency surgery or blood transfusion. All of the perforations were resolved using endoscopic clipping or hemostasis. The other problematic complication observed was pneumonia, which was treated with conservative therapy.

| Total | Esophagus | Stomach | Duodenum | Colorectum | |

| Patients, n | 873 | 59 | 681 | 4 | 129 |

| Age (yr), mean (range) | 69.9 (44-91) | 68.0 (46-81) | 70.9 (45-91) | 65.5 (54-77) | 65.9 (44-80) |

| Sex (male:female), n | 549:324 | 52:7 | 408:273 | 2:2 | 87:42 |

| Lesions, n | 1047 | 64 | 850 | 4 | 129 |

| Tumor size (mm), mean (range) | 22.2 (2-150) | 23 (4-46) | 20.8 (2-150) | 16.8 (9-31) | 31.6 (2-92) |

| Tumor diagnosis and depth, n | |||||

| Benign tumor | 121 | 0 | 86 | 0 | 35 |

| Cancer (m) | 808 | 56 | 668 | 4 | 80 |

| Cancer (sm1) | 61 | 4 | 48 | 0 | 9 |

| Cancer (sm2 or deeper) | 57 | 4 | 48 | 0 | 5 |

| En bloc resection rate, % | 94.3 | 96.9 | 95.8 | 100 | 79.8 |

| Operation time (min), mean (range) | 46 (4-360) | 62 (48-206) | 42 (4-360) | 90 (50-114) | 60 (7-300) |

| Complications associated with ESD, n (%) | |||||

| Perforation | 12 (1.1) | 1 (1.7) | 9 (1.1) | 1 (25.0) | 1 (0.8) |

| Postoperative bleeding | 53 (5.1) | 0 (0.0) | 51 (6.0) | 1 (25.0) | 1 (0.8) |

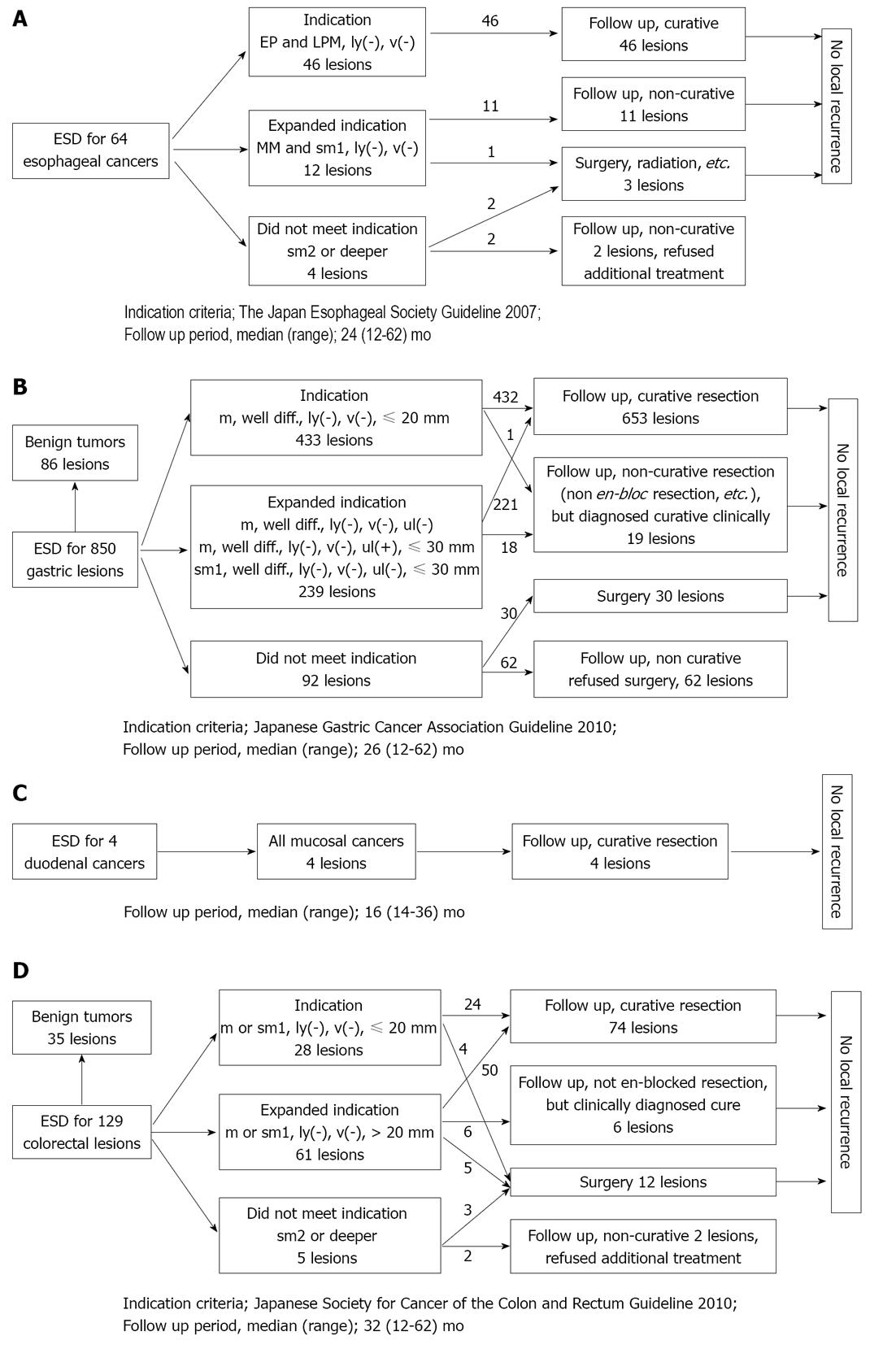

The follow-up results of the 64 patients with esophageal cancer are shown in Figure 2A. The median follow-up period was 24 mo (range: 12-62 mo). Forty-six patients met the absolute indication criteria of the guidelines issued by the Japan Esophageal Society in 2007[14]. Twelve patients with lesions did not meet the conventional absolute criteria and instead met expanded indication criteria. Four patients did not meet the indication criteria. The en bloc resection rate was 96.9%. One of the 12 patients who met the expanded indication criteria and two of the four patients who did not meet the indication criteria received additional treatment. No local recurrences were observed in the patients who met the indication criteria.

The follow-up results of the 850 patients with gastric tumors (764 patients with cancer, 82 patients with adenomas and 4 others) are shown in Figure 2B. The median follow-up period was 26 mo (range: 12-62 mo). Four hundred and thirty-three of the 764 patients with gastric cancer met the absolute indication criteria of the guidelines issued by the Japanese Gastric Cancer Association in 2010[15]. Two hundred and thirty-nine patients with lesions did not meet the conventional absolute indication criteria and instead met expanded indication criteria. Ninety-two patients with lesions exceeded the indication criteria. The en bloc resection rate was 95.8%. Curative resection was achieved in 653 of the 764 patients with gastric cancer (85.5%). Nineteen patients with lesions underwent non-curative resection (non en bloc resection was performed, etc.) but were diagnosed curative clinically. No local recurrences were observed in the patients who met the indication criteria or in those who underwent clinically curative resection.

The follow-up results of the four patients with duodenal cancer are shown in Figure 2C. The median follow-up period was 16 mo (range: 14-36 mo). All four patients underwent curative resection, and the en bloc resection rate was 100%.

The follow-up results of the 129 patients with colorectal tumors (C: 94 patients with cancer, 21 patients with adenomas and 14 others) are shown in Figure 2D. The median follow-up period was 32 mo (range: 12-62 mo). Twenty-eight of the 94 patients with colorectal cancer met the absolute indication criteria of the guidelines issued by the Japanese Society for Cancer of the Colon and Rectum in 2010[16]. Sixty-one patients with lesions did not meet the conventional absolute indication criteria and instead met expanded indication criteria. Five patients with lesions exceeded the indication criteria. The en bloc resection rate was 79.8%. Curative resection was achieved in 74 of the 94 patients with colorectal cancer (78.7%). Six patients with lesions underwent non-curative resection (because non en bloc resection was performed, etc.) but were diagnosed curative clinically. No local recurrences were observed in the patients who met the indication criteria or in those who underwent clinically curative resection.

No mortal complications were observed in association with the ESD procedures. Perforations occurred in 12 cases (1.1%, E: 1 case, G: 9 cases, D: 1 case, C: 1 case) and postoperative bleeding occurred in 53 cases (5.1%, G: 51 cases, D: 1 case, C: 1 case) (Table 1). No problematic complications related to sedation were observed. One patient who experienced postoperative pneumonia was treated with an infusion of antibiotics and recovered in one week.

Operation times and tumor size for the cases with and without complications are shown in Table 2. Because the number of esophageal, duodenal and colorectal cases complicated by perforation or bleeding was small, it was not possible to make a statistical comparison between a no complication group and a complication group. It was possible to analyze the cases of gastric lesions statistically. Tumor size and operation times in the gastric cases with perforations were significantly larger than those observed in the cases without complications (P < 0.05).

| Number of lesions | Size of treated lesions (mm) | Operation time (min) | |

| Esophagus | |||

| All lesions | 64 | 23.0 ± 11.0 | 76.4 ± 45.4 |

| No complication | 58 | 23.0 ± 11.1 | 76.4 ± 45.7 |

| Complication | |||

| Perforation | 1 | 24 | 57 |

| Postoperative bleeding | 0 | ND | ND |

| Stomach | |||

| All lesions | 850 | 20.2 ± 13.4 | 63.2 ± 47.2 |

| No complication | 791 | 19.9 ± 13.2 | 62.1 ± 46.9 |

| Complication | |||

| Perforation | 8 | 31.7 ± 14.7a | 108.9 ± 45.7a |

| Postoperative bleeding | 51 | 23.5 ± 15.5 | 73.1 ± 47.9a |

| Duodenum | |||

| All lesions | 4 | 16.8 ± 10.1 | 94.5 ± 29.9 |

| No complication | 2 | 20.0 ± 15.6 | 112.0 ± 2.8 |

| Complication | |||

| Perforation | 1 | 10 | 104 |

| Postoperative bleeding | 1 | 17 | 50 |

| Colorectum | |||

| All lesions | 129 | 31.6 ± 16.5 | 86.6 ± 66.4 |

| No complication | 127 | 31.3 ± 16.4 | 84.5 ± 64.5 |

| Complication | |||

| Perforation | 1 | 35 | 135 |

| Postoperative bleeding | 1 | 65 | 300 |

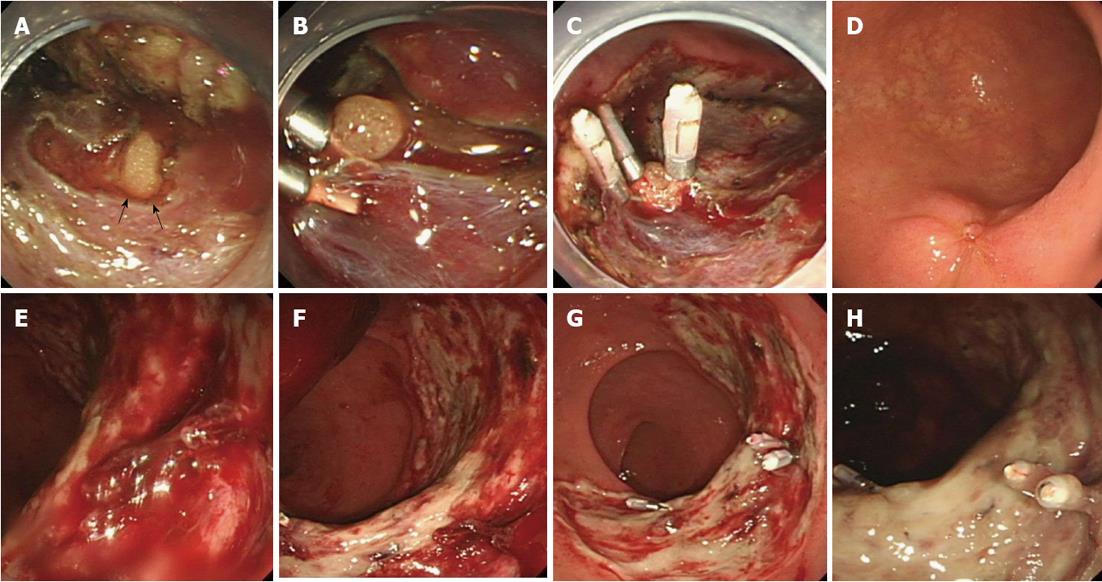

All perforations were managed endoscopically using endoclips, a patch of omentum or conservative therapy. None of the patients with perforations required further surgery, and each of these patients were hospitalized for an additional zero to two days. A representative case of perforation is shown in Figure 3. Briefly, after detecting a perforation hole, the air was removed using an endoscopic fiber. Next, endoscopic clipping was performed. When the omentum became visible through the perforation hole, we attempted to aspirate the omentum through the perforation hole and clip the omentum to the hole.

All cases of intraoperative bleeding were controlled with endoscopic procedures such as soft coagulation with hemostatic forceps (Coagrasper; FD-410LR or FD-410QR, Olympus, Tokyo). No case of intraoperative bleeding required surgical intervention or blood transfusion. Postoperative bleeding occurred in 53 cases. Early postoperative bleeding (within three days of ESD) occurred in 25/53 cases and delayed postoperative bleeding (more than three days after ESD) occurred in 28/53 lesions. All cases of postoperative bleeding were controlled with endoscopic treatment (clipping and/or electrocoagulation). No case of postoperative bleeding required surgical intervention or blood transfusion. A representative case of bleeding treated endoscopically is shown in Figure 3. Briefly, bleeding from a post-ESD ulcer was detected. After removing the coagulation, the bleeding point was detected. Clips were used to achieve hemostasis endoscopically.

ESD allows for the treatment of large and ulcerative lesions and has revolutionized the management of gastrointestinal tumors[6,7,17,18]. ESD is a minimally invasive treatment for gastrointestinal cancer. However, ESD requires a high level of expertise and experience[19,20]. It is usually performed in general hospitals because of the high frequency of complications and the need for a high level of technical skill. Hemostatic devices and/or endoscopic clipping prevents the occurrence of complications after ESD. In this study, all complications of ESD were resolved using non-surgical therapies. Therefore, ESD can be safely performed in clinics with established therapeutic methods and medical services to address potential complications. This study showed that ESD can be safely performed in small clinics.

Since ESD is an endoscopic surgical procedure, the risk of complications is unavoidable[13]. Bleeding and perforation are most common complications of ESD procedures[13]. The incidence of complications[13] associated with ESD are reported to be: 0% for bleeding in the esophagus, 4.0%-6.0% for perforation of the esophagus[21,22], 1.8%-15.6% for bleeding in the stomach, 1.2%-4.7% for perforation of the stomach[23-26], 0.3%-1.5% for bleeding in the colon and 2.2%-5.5% for perforation of the colon[27-29]. Except in cases of esophageal ESD, bleeding is a common complication. It can be treated endoscopically using soft coagulation with hemostatic forceps or hemoclips[13]. In most reports, the incidence of bleeding is less than 10%[13]. In this study, the incidence of complications was 0% for bleeding in the esophagus, 1.7% for perforation of the esophagus, 6.0% for bleeding in the stomach, 1.1% for perforation of the stomach, 0.8% for bleeding in the colon and 0.8% for perforation of the colon. These complication rates are acceptable in comparison to those seen at other institutes[13].

Perforation is another common complication of ESD. Since mediastinitis and peritonitis occuring consequent to esophageal perforation and colon perforation, respectively, have high mortality rates, surgery was previously the method of choice for treating gastrointestinal perforations. Currently, conservative or endoscopic treatment tends to be selected to treat smaller perforations when the lesions are clean[30,31]. Most perforations resulting from ESD are smaller and tend to be treated in a non-surgical manner[32,33]. It is very important to recognize the occurrence of a perforation immediately. Endoscopic closure should be considered if the lesion is clean (i.e. without feces and so on). Matsui et al[13] have suggested the indications for endoscopic clipping of perforations to include (1) a small defect size (less than 10 mm); (2) the ability to prepare the bowel adequately; and (3) a stable patient condition immediate following perforation. After successful endoscopic closure is completed, the patient should be fasted and treated with antibiotics. Formal guidelines for fasting periods have not been established; however, one report regarding colonic perforations indicates a mean fasting period of 4.2 d and a mean duration of intravenous antibiotics of 5.5 d[34]. Surgical treatment should be considered when the perforated lesion cannot be closed with endoclips, abdominal pain has exacerbated or severe peritonitis is suspected. Of course, if there is any concern regarding the patient’s condition, the patient should be transferred to surgery without hesitation. In this study, all perforations were managed endoscopically using endoclips, patches of the omentum or conservative therapy. No patient required additional surgery due to perforation in this study.

Because ESD requires a high level of technical skill, an endoscopist’s skill level[9-12], rather than the size of a clinic or hospital, may be more strongly related to the results of ESD, such as the success of en bloc resections, the length of operations and the rate of complications. In this study, all five endoscopists had more than 10 years of experience with endoscopic treatment, including EMR. Furthermore, all ESD procedures were supervised by the most experienced endoscopist in our clinic. As a result, all ESD cases received similar levels of treatment. This is one of the important reasons why ESD can be safely performed in small clinics. The patient volume may also strongly affect the ESD results. In this study, a total of 1047 lesions in 873 patients were treated during the five-year period, averaging approximately 210 ESDs each year. This is considered to be a moderate to high patient volume. Many experiences with cases and a relatively high patient volume are also needed for the improvement of ESD skills and were found to be important for safely performing ESD.

Two patients with cancer of the esophagus, 62 patients with cancer of the stomach and two patients with cancer of the colon refused additional treatment/surgery in spite of a non-curative resection in this study. The reasons for refusing additional treatment/surgery were varied, including advanced age, complicated diseases, etc. The long-term outcomes for such non-curative ESD patients who refused additional treatment/surgery may be of interest. It also may be important data for deciding on the indications for the treatment of elderly patients. However, we did not analyze the overall data in terms of the long-term outcomes for such non-curative ESD patients in this study, so a future study will be needed to clarify these issues.

In conclusion, ESD is associated with a few problematic complications. However, in this study, all complications were resolved using non-surgical therapies such as endoscopic clipping. ESD can be safely performed in clinics with established therapeutic methods and medical services to address potential complications.

Endoscopic submucosal dissection (ESD) is a minimally invasive treatment for gastrointestinal cancer. It is usually performed in general hospitals because of the high frequency of complications and the need for a high level of technical skill. The aim of this study was to determine whether ESD can be safely performed at small clinics. The efficacy, technical feasibility and associated complications of the procedures were assessed.

ESD is usually performed in general hospitals. Treatment data and outcome of ESD at general hospitals were reported. However, such reports from clinics were rare. The efficacy, technical feasibility and associated complications of the ESD procedures at a local clinic were assessed.

This study showed that ESD can be safely performed in clinics with established therapeutic methods and medical services to address potential complications. ESD is associated with a few problematic complications. However, in this study, all complications were resolved using non-surgical therapies such as endoscopic clipping.

ESD can be safely performed in clinics with established therapeutic methods and medical services to address potential complications.

ESD is a minimally invasive treatment for gastrointestinal cancer. One-piece resection is considered the gold standard for endoscopic treatment because it provides an accurate histological assessment and reduces the risk of recurrence. ESD enable us to resect large and ulcerative lesions en bloc.

This study investigated whether ESD can be safely performed at small clinics. The authors indicated ESD can be safely performed in their small 19-bed clinic with similar ESD results as previously published from general hospitals. This is an interesting topic.

P- Reviewers Oda I, Fujishiro M S- Editor Huang XZ L- Editor A E- Editor Xiong L

| 1. | Ono H, Kondo H, Gotoda T, Shirao K, Yamaguchi H, Saito D, Hosokawa K, Shimoda T, Yoshida S. Endoscopic mucosal resection for treatment of early gastric cancer. Gut. 2001;48:225-229. [PubMed] [DOI] [Cited in This Article: ] [Cited by in Crossref: 1134] [Cited by in F6Publishing: 1104] [Article Influence: 48.0] [Reference Citation Analysis (4)] |

| 2. | Ahmad NA, Kochman ML, Long WB, Furth EE, Ginsberg GG. Efficacy, safety, and clinical outcomes of endoscopic mucosal resection: a study of 101 cases. Gastrointest Endosc. 2002;55:390-396. [PubMed] [DOI] [Cited in This Article: ] [Cited by in Crossref: 273] [Cited by in F6Publishing: 296] [Article Influence: 13.5] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 3. | Hirao M, Masuda K, Asanuma T, Naka H, Noda K, Matsuura K, Yamaguchi O, Ueda N. Endoscopic resection of early gastric cancer and other tumors with local injection of hypertonic saline-epinephrine. Gastrointest Endosc. 1998;34:264-269. [PubMed] [DOI] [Cited in This Article: ] [Cited by in Crossref: 270] [Cited by in F6Publishing: 250] [Article Influence: 6.9] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 4. | Tada M, Murakami A, Karita M, Yanai H, Okita K. Endoscopic resection of early gastric cancer. Endoscopy. 1993;25:445-450. [PubMed] [DOI] [Cited in This Article: ] [Cited by in Crossref: 297] [Cited by in F6Publishing: 289] [Article Influence: 9.3] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 5. | Kojima T, Parra-Blanco A, Takahashi H, Fujita R. Outcome of endoscopic mucosal resection for early gastric cancer: review of the Japanese literature. Gastrointest Endosc. 1998;48:550-554; discussion 554-555. [PubMed] [DOI] [Cited in This Article: ] [Cited by in Crossref: 201] [Cited by in F6Publishing: 211] [Article Influence: 8.1] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 6. | Gotoda T, Kondo H, Ono H, Saito Y, Yamaguchi H, Saito D, Yokota T. A new endoscopic mucosal resection procedure using an insulation-tipped electrosurgical knife for rectal flat lesions: report of two cases. Gastrointest Endosc. 1999;50:560-563. [PubMed] [DOI] [Cited in This Article: ] [Cited by in Crossref: 320] [Cited by in F6Publishing: 330] [Article Influence: 13.2] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 7. | Yamamoto H, Kawata H, Sunada K, Sasaki A, Nakazawa K, Miyata T, Sekine Y, Yano T, Satoh K, Ido K. Successful en-bloc resection of large superficial tumors in the stomach and colon using sodium hyaluronate and small-caliber-tip transparent hood. Endoscopy. 2003;35:690-694. [PubMed] [DOI] [Cited in This Article: ] [Cited by in Crossref: 288] [Cited by in F6Publishing: 290] [Article Influence: 13.8] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 8. | Oda I, Gotoda T, Hamanaka H, Eguchi T, Saito Y, Matsuda T, Bhandari P, Emura F, Saito D, Ono H. Endscopic submucosal dissection for early gastric cancer: Technical feasibility, operation time and complications from a large consecutive series. Dig Endosc. 2005;17:54-58. [DOI] [Cited in This Article: ] [Cited by in Crossref: 336] [Cited by in F6Publishing: 345] [Article Influence: 18.2] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 9. | Onozato Y, Ishihara H, Iizuka H, Sohara N, Kakizaki S, Okamura S, Mori M. Endoscopic submucosal dissection for early gastric cancers and large flat adenomas. Endoscopy. 2006;38:980-986. [PubMed] [DOI] [Cited in This Article: ] [Cited by in Crossref: 101] [Cited by in F6Publishing: 117] [Article Influence: 6.5] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 10. | Onozato Y, Kakizaki S, Ishihara H, Iizuka H, Sohara N, Okamura S, Mori M, Itoh H. Endoscopic submucosal dissection for rectal tumors. Endoscopy. 2007;39:423-427. [PubMed] [DOI] [Cited in This Article: ] [Cited by in Crossref: 68] [Cited by in F6Publishing: 76] [Article Influence: 4.5] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 11. | Iizuka H, Okamura S, Onozato Y, Ishihara H, Kakizaki S, Mori M. Endoscopic submucosal dissection for colorectal tumors. Gastroenterol Clin Biol. 2009;33:1004-1011. [PubMed] [DOI] [Cited in This Article: ] [Cited by in Crossref: 27] [Cited by in F6Publishing: 32] [Article Influence: 2.1] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 12. | Onozato Y, Kakizaki S, Ishihara H, Iizuka H, Sohara N, Sohara N, Okamura S, Mori M. Feasibility of endoscopic submucosal dissection for elderly patients with early gastric cancers and adenomas. Dig Endosc. 2008;20:12-16. [DOI] [Cited in This Article: ] [Cited by in Crossref: 15] [Cited by in F6Publishing: 16] [Article Influence: 0.9] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 13. | Matsui N, Akahoshi K, Nakamura K, Ihara E, Kita H. Endoscopic submucosal dissection for removal of superficial gastrointestinal neoplasms: A technical review. World J Gastrointest Endosc. 2012;4:123-136. [PubMed] [DOI] [Cited in This Article: ] [Cited by in CrossRef: 32] [Cited by in F6Publishing: 30] [Article Influence: 2.5] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 14. | The Japan Esophageal Society. Guidelines for the Diagnosis and Treatment of Esophageal Cancer. Tokyo: Kanehara & Co. Ltd 2007; . [Cited in This Article: ] |

| 15. | Japanese Gastric Cancer Association. Japanese gastric cancer treatment guidelines 2010 (ver. 3). Gastric Cancer. 2011;14:113-123. [PubMed] [DOI] [Cited in This Article: ] [Cited by in Crossref: 1723] [Cited by in F6Publishing: 1840] [Article Influence: 141.5] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 16. | Watanabe T, Itabashi M, Shimada Y, Tanaka S, Ito Y, Ajioka Y, Hamaguchi T, Hyodo I, Igarashi M, Ishida H. Japanese Society for Cancer of the Colon and Rectum (JSCCR) guidelines 2010 for the treatment of colorectal cancer. Int J Clin Oncol. 2012;17:1-29. [PubMed] [DOI] [Cited in This Article: ] [Cited by in Crossref: 528] [Cited by in F6Publishing: 559] [Article Influence: 43.0] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 17. | Yamamoto H. Endoscopic submucosal dissection of early cancers and large flat adenomas. Clin Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2005;3:S74-S76. [PubMed] [DOI] [Cited in This Article: ] [Cited by in Crossref: 81] [Cited by in F6Publishing: 90] [Article Influence: 4.7] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 18. | Hirasawa K, Kokawa A, Oka H, Yahara S, Sasaki T, Nozawa A, Tanaka K. Superficial adenocarcinoma of the esophagogastric junction: long-term results of endoscopic submucosal dissection. Gastrointest Endosc. 2010;72:960-966. [PubMed] [DOI] [Cited in This Article: ] [Cited by in Crossref: 70] [Cited by in F6Publishing: 80] [Article Influence: 5.7] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 19. | Ohkuwa M, Hosokawa K, Boku N, Ohtu A, Tajiri H, Yoshida S. New endoscopic treatment for intramucosal gastric tumors using an insulated-tip diathermic knife. Endoscopy. 2001;33:221-226. [PubMed] [DOI] [Cited in This Article: ] [Cited by in Crossref: 295] [Cited by in F6Publishing: 314] [Article Influence: 13.7] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 20. | Rösch T, Sarbia M, Schumacher B, Deinert K, Frimberger E, Toermer T, Stolte M, Neuhaus H. Attempted endoscopic en bloc resection of mucosal and submucosal tumors using insulated-tip knives: a pilot series. Endoscopy. 2004;36:788-801. [PubMed] [DOI] [Cited in This Article: ] [Cited by in Crossref: 181] [Cited by in F6Publishing: 198] [Article Influence: 9.9] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 21. | Oyama T, Tomori A, Hotta K, Morita S, Kominato K, Tanaka M, Miyata Y. Endoscopic submucosal dissection of early esophageal cancer. Clin Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2005;3:S67-S70. [PubMed] [DOI] [Cited in This Article: ] [Cited by in Crossref: 438] [Cited by in F6Publishing: 430] [Article Influence: 22.6] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 22. | Ono S, Fujishiro M, Niimi K, Goto O, Kodashima S, Yamamichi N, Omata M. Long-term outcomes of endoscopic submucosal dissection for superficial esophageal squamous cell neoplasms. Gastrointest Endosc. 2009;70:860-866. [PubMed] [DOI] [Cited in This Article: ] [Cited by in Crossref: 311] [Cited by in F6Publishing: 319] [Article Influence: 21.3] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 23. | Kato M, Nishida T, Tsutsui S, Komori M, Michida T, Yamamoto K, Kawai N, Kitamura S, Zushi S, Nishihara A. Endoscopic submucosal dissection as a treatment for gastric noninvasive neoplasia: a multicenter study by Osaka University ESD Study Group. J Gastroenterol. 2011;46:325-331. [PubMed] [DOI] [Cited in This Article: ] [Cited by in Crossref: 79] [Cited by in F6Publishing: 88] [Article Influence: 6.8] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 24. | Mannen K, Tsunada S, Hara M, Yamaguchi K, Sakata Y, Fujise T, Noda T, Shimoda R, Sakata H, Ogata S. Risk factors for complications of endoscopic submucosal dissection in gastric tumors: analysis of 478 lesions. J Gastroenterol. 2010;45:30-36. [PubMed] [DOI] [Cited in This Article: ] [Cited by in Crossref: 110] [Cited by in F6Publishing: 119] [Article Influence: 8.5] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 25. | Isomoto H, Shikuwa S, Yamaguchi N, Fukuda E, Ikeda K, Nishiyama H, Ohnita K, Mizuta Y, Shiozawa J, Kohno S. Endoscopic submucosal dissection for early gastric cancer: a large-scale feasibility study. Gut. 2009;58:331-336. [PubMed] [DOI] [Cited in This Article: ] [Cited by in Crossref: 470] [Cited by in F6Publishing: 496] [Article Influence: 33.1] [Reference Citation Analysis (1)] |

| 26. | Chung IK, Lee JH, Lee SH, Kim SJ, Cho JY, Cho WY, Hwangbo Y, Keum BR, Park JJ, Chun HJ. Therapeutic outcomes in 1000 cases of endoscopic submucosal dissection for early gastric neoplasms: Korean ESD Study Group multicenter study. Gastrointest Endosc. 2009;69:1228-1235. [PubMed] [DOI] [Cited in This Article: ] [Cited by in Crossref: 429] [Cited by in F6Publishing: 447] [Article Influence: 29.8] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 27. | Saito Y, Uraoka T, Yamaguchi Y, Hotta K, Sakamoto N, Ikematsu H, Fukuzawa M, Kobayashi N, Nasu J, Michida T. A prospective, multicenter study of 1111 colorectal endoscopic submucosal dissections (with video). Gastrointest Endosc. 2010;72:1217-1225. [PubMed] [DOI] [Cited in This Article: ] [Cited by in Crossref: 497] [Cited by in F6Publishing: 535] [Article Influence: 38.2] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 28. | Fujishiro M, Yahagi N, Kakushima N, Kodashima S, Muraki Y, Ono S, Yamamichi N, Tateishi A, Oka M, Ogura K. Outcomes of endoscopic submucosal dissection for colorectal epithelial neoplasms in 200 consecutive cases. Clin Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2007;5:678-683; quiz 645. [PubMed] [DOI] [Cited in This Article: ] [Cited by in Crossref: 250] [Cited by in F6Publishing: 281] [Article Influence: 16.5] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 29. | Toyonaga T, Man-i M, Fujita T, East JE, Nishino E, Ono W, Morita Y, Sanuki T, Yoshida M, Kutsumi H. Retrospective study of technical aspects and complications of endoscopic submucosal dissection for laterally spreading tumors of the colorectum. Endoscopy. 2010;42:714-722. [PubMed] [DOI] [Cited in This Article: ] [Cited by in Crossref: 89] [Cited by in F6Publishing: 101] [Article Influence: 7.2] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 30. | Wesdorp IC, Bartelsman JF, Huibregtse K, den Hartog Jager FC, Tytgat GN. Treatment of instrumental oesophageal perforation. Gut. 1984;25:398-404. [PubMed] [DOI] [Cited in This Article: ] [Cited by in Crossref: 84] [Cited by in F6Publishing: 88] [Article Influence: 2.2] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 31. | Yoshikane H, Hidano H, Sakakibara A, Ayakawa T, Mori S, Kawashima H, Goto H, Niwa Y. Endoscopic repair by clipping of iatrogenic colonic perforation. Gastrointest Endosc. 1997;46:464-466. [PubMed] [DOI] [Cited in This Article: ] [Cited by in Crossref: 118] [Cited by in F6Publishing: 121] [Article Influence: 4.5] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 32. | Minami S, Gotoda T, Ono H, Oda I, Hamanaka H. Complete endoscopic closure of gastric perforation induced by endoscopic resection of early gastric cancer using endoclips can prevent surgery (with video). Gastrointest Endosc. 2006;63:596-601. [PubMed] [DOI] [Cited in This Article: ] [Cited by in Crossref: 243] [Cited by in F6Publishing: 222] [Article Influence: 12.3] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 33. | Neuhaus H, Costamagna G, Devière J, Fockens P, Ponchon T, Rösch T. Endoscopic submucosal dissection (ESD) of early neoplastic gastric lesions using a new double-channel endoscope (the “R-scope”). Endoscopy. 2006;38:1016-1023. [PubMed] [DOI] [Cited in This Article: ] [Cited by in Crossref: 96] [Cited by in F6Publishing: 107] [Article Influence: 5.9] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 34. | Taku K, Sano Y, Fu KI, Saito Y, Matsuda T, Uraoka T, Yoshino T, Yamaguchi Y, Fujita M, Hattori S. Iatrogenic perforation associated with therapeutic colonoscopy: a multicenter study in Japan. J Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2007;22:1409-1414. [PubMed] [DOI] [Cited in This Article: ] [Cited by in Crossref: 131] [Cited by in F6Publishing: 117] [Article Influence: 6.9] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |