Published online Feb 7, 2006. doi: 10.3748/wjg.v12.i5.784

Revised: July 9, 2005

Accepted: August 3, 2005

Published online: February 7, 2006

AIM: To determine the efficacy of an interferon alpha and ribavirin combination treatment for Japanese patients infected with hepatitis C virus (HCV) of genotype 2, a multi-center study was retrospectively analyzed.

METHODS: In total, 173 patients with HCV genotype 2 started to receive interferon-alpha subcutaneously thrice a week and 600–800 mg of ribavirin daily for 24 wk.

RESULTS: The overall sustained virological response (SVR), defined as undetectable HCV RNA in serum, 24 wk after the end of treatment, was remarkably high by 84.4 %, (146/173) by an intention-to-treat analysis. A significant difference in SVR was found between patients with and without the discontinuation of ribavirin (46.9% vs 92.9 %), but no difference was found between those with and without a dose reduction of ribavirin. A significant difference in SVR was also found between patients with less than 16 wk and patients with 16 or more weeks of ribavirin treatment (34.8 % vs 92.0 %).

CONCLUSION: The 24-wk interferon and ribavirin treatment is highly effective for Japanese patients with HCV genotype 2. The significant predictor of SVR is continuation of the ribavirin treatment for up to 16 weeks.

- Citation: Furusyo N, Katoh M, Tanabe Y, Kajiwara E, Maruyama T, Shimono J, Sakai H, Nakamuta M, Nomura H, Masumoto A, Shimoda S, Takahashi K, Azuma K, Hayashi J, Group KULDS. Interferon alpha plus ribavirin combination treatment of Japanese chronic hepatitis C patients with HCV genotype 2: A project of the Kyushu University Liver Disease Study Group. World J Gastroenterol 2006; 12(5): 784-790

- URL: https://www.wjgnet.com/1007-9327/full/v12/i5/784.htm

- DOI: https://dx.doi.org/10.3748/wjg.v12.i5.784

The heterogeneity of the hepatitis C virus (HCV) genome has warranted the classification of the virus into different genotypes, with six major genotypes and more than 50 subtypes of HCV having been described till date[1-3]. The different genotypes may be important to the pathogenesis of the disease[4], response to antiviral therapy[5], and the diagnosis[6], as shown by molecular epidemiological studies and research on vaccine development.

A currently popular treatment regimen for the treatment of chronic HCV infection in the world is pegylated interferon (IFN) alpha in combination with ribavirin. However, there was no data of response to such combination treatment for Japanese patients, because the treatment was just approved by the Japanese Minister of Health, Labour and Welfare in December 2004. Treatment with these drugs has resulted in a high rate of sustained virological response (SVR), over 50 %[7,8]; however, the treatment duration is long, 48 wk and it causes various side effects, which are sometimes serious. Such a combination treatment is also expensive; a 24-wk treatment course costs approximately $20 000[9]. The efficacy and economic aspects need to be analyzed. Quite recently, a very short duration treatment for acute hepatitis C was shown to be highly effective[10].

The HCV genotype has been reported to be the most important predictor of IFN treatment response[7-13]. Patients infected with genotypes 2 and 3 have achieved about 65 % SVR in a trial of 24-wk IFN alpha in combination with ribavirin, in contrast to patients with genotype 1 who had under 30 % SVR[14,15]. Recently, multicenter studies in Europe and North America showed that patients with genotypes 2 and 3 were able to achieve a high SVR in a trial of 14-16 wk of pegylated IFN alpha in combination with ribavirin[16,17]. However, their analysis included very few genotype 2 patients: one included 23 genotype 2 patients and the other had 43 patients.

The distribution of HCV genotypes in Japan includes about 70 % genotype 1b, with the remaining 30 % genotypes 2a and 2b[18]. The SVRs to treatment of even shorter duration have not yet been reported for Japanese patients. Data are needed to define whether or not the duration of treatment with IFN alpha in combination with ribavirin can be reduced from 24 wk without compromising antiviral efficacy in patients chronically infected with HCV of genotype 2. This investigation has assessed the efficacy of a 24-wk combination treatment of IFN alpha and ribavirin for Japanese patients with HCV genotype 2 infection and focussed on the issue of the relationship between the duration of treatment and the efficacy.

A retrospective study was done on Japanese patients treated between December 2000 and March 2004 that included 173 patients, 20 years or older, who satisfied the following criteria: (1) chronically infected with HCV genotype 2a or 2b; and (2) a history of an increased alanine aminotransferase (ALT) level for over 6 months. Criteria for exclusion were: (1) clinical or biochemical evidence of hepatic decompensation; (2) hemoglobin level less than 115 g/L, white blood cell count less than 3 × 109/L, and platelet count less than 50 × 109/L; (3) concomitant liver disease other than hepatitis C (hepatitis B surface antigen- or human immunodeficiency virus-positive); (4) alcohol or drug abuse; (5) suspected hepatocellular carcinoma; (6) severe psychiatric disease; and (7) treatment with antiviral or immunosuppressive agents prior to enrolment. Patients who fulfilled the above criteria were recruited at Kyushu University Hospital and 32 affiliated hospitals in the northern Kyushu area of Japan.

Informed consent was obtained from all the patients before enrollment in this study. The study was approved by the institutional Ethics Committees of the hospitals involved and conducted in accordance with the ethical guidelines of the Declaration of Helsinki and the International Conference on Harmonization of guidelines for good clinical practice.

All patients were treated with 6 -10 MU of IFN alpha-2b (Intron A; Schering-Plough, Osaka, Japan) subcutaneously daily for the first 2 wk, then thrice a week for 22 wk. Ribavirin (Rebetol; Schering-Plough) was administrated orally for 24 wk at a daily dose of 600 - 800 mg based on the body weight (600 mg for patients weighing less than 60 kg and 800 mg for those weighing 60 kg or more). The above duration and dose were approved by the Japanese Minister of Health, Labour and Welfare. The 48-wk combination treatment and the ribavirin dosage of 1 000-1 200 mg recommended by the international guidelines were not permitted under the rules of the Japanese national health insurance system during the period of this study. The dose of ribavirin was reduced by 200 mg if the hemoglobin level fell to 100 g/L. Patients were considered to have ribavirin-induced anemia if the hemoglobin level decreased to less than 100 g/L. In such cases, a reduction in the dose of ribavirin was required. Both IFN alpha-2b and ribavirin were discontinued if the hemoglobin level, white blood cell count, or platelet count fell below 85 g/L, 1 × 109/L, and 2.5 × 109/L, respectively. The treatment was also discontinued if severe malaise developed, the continuation of treatment was judged not to be possible by the attending physician, or the patient desired to discontinue treatment.

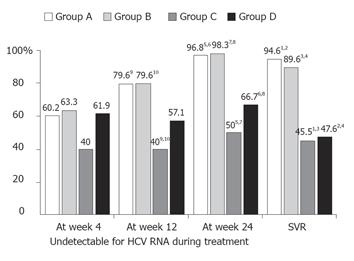

Patients were divided into the following four categories: Group A, patients who well tolerated the 24-wk comb-ination treatment with IFN and ribavirin without a reduction in the dose of either drug; Group B, patients who received the full 24-wk combination treatment but who needed a reduction of the dose of IFN or ribavirin, or both; Group C, patients who discontinued the ribavirin treatment but continued the 24-wk IFN treatment; and Group D, patients who did not complete the 24 wk of treatment, because of adverse effects or who dropped out.

The serum HCV RNA level was examined with an Amplicor HCV monitor assay (version 2.0) (Roche, Tokyo, Japan), with a lower limit of quantitation of 500 IU (135 copies/mL) and an outer limit of quantitation of 850 000 IU/mL. Samples with HCV RNA over the limit of 850 000 IU/L were not diluted to determine the levels between 850 000-5 000 000 IU/mL. HCV RNA was also examined with the qualitative Amplicor HCV assay (Roche). HCV genotype was determined by type-specific primer from the core region of the HCV genome. The protocol for genotyping was carried out as described earlier[11,12].

Liver biopsy was done for 117 patients infected with genotype 2 within the 6 months before the start of the treatment. For each specimen, a stage of fibrosis and a grade of activity were established according to the following criteria. Fibrosis was staged on a scale of 0 - 4: F0 = no fibrosis, F1 = portal fibrosis without septa, F2 = few septa, F3 = numerous septa without cirrhosis, F4 = cirrhosis. The grading of activity, including the intensity of the necroinflammation, was scored as follows: A0 = no histological activity, A1= mild activity, A2 = moderate activity, A3 = severe activity. Liver biopsy was not available from 56 patients who declined to have a biopsy.

The SVR was defined as undetectable HCV RNA by the qualitative Amplicor HCV assay (Roche) and a normal ALT level (under 40 IU/L) at 6 months after the end or stoppage of the treatment. Patients not achieving a SVR were considered as non-SVR. Patients who had undetectable HCV RNA within 4 wk of the start of treatment were considered to have had an early virological response (EVR).

The analysis of SVR was done on an intention-to-treatment basis, including dropouts, who were counted as non-sustained virological responders, and patients who stopped treatment. The χ2 test or Fisher’s exact test was used to examine the association between baseline characteristics and SVR. The Mann-Whitney U test was also used to compare responders and non-responders with regard to various characteristics, when appropriate. Independent factors associated with SVR were studied using forward stepwise logistic regression analysis of the variables. Forward stepwise logistic regression analysis was done using a commercially available software package (BMDP Statistical Software Inc., Los Angeles, CA, USA) for the IBM 3090 system computer. A P-value of less than 0.05 was considered significant. All P-values were two tailed.

The distribution of Groups A, B, C, and D patients was 93 (53.8 %), 48 (27.7 %), 11 (6.4 %), and 21 (12.1 %), re-spectively. Completing the 24-week ribavirin treatment were 141 patients in Groups A and B. Thirty-two patients of Groups C and D discontinued the ribavirin treatment. The pretreatment characteristics of these four groups of patients are summarized in Table 1 and 2. The median age was significantly younger in Group A (51 years) than in Groups B (56 years) and C (59 years). Significantly more men were in Group A (71.0 %) than in Group B (33.3 %). The median creatinine clearance was significantly higher in Group A (110 mL/min) than Groups B (92 mL/min) and C (85 mL/min). The median hemoglobin level was significantly higher in Group A (150 g/L) than Groups B (136 g/L), C (134 g/L), and D (134 g/L). The median platelet count was significantly higher in Group A (168×109/L) than in Group C (127×109/L). No notable differences between the groups were found in body weight, ribavirin dose, HCV RNA level, genotype, or histology.

| Complete Ribavirin treatment(n = 141) | Discontinued Ribavirin treatment(n = 32) | All patients | |||

| Group A | Group B | Group C | Group D | ||

| Characteristic | (n = 93) | (n = 48) | (n = 11) | (n = 21) | (n = 173) |

| Median age (yr) | 5112 | 561 | 592 | 50 | 53 |

| (range) | (20 - 73) | (25 - 70) | (53 - 73) | (29 - 73) | (20 - 73) |

| Male (%) | 66 (71.0)3 | 16 (33.3)3 | 5(50.0) | 13 (61.9) | 100 (57.8) |

| Body weight | |||||

| 60 kg or more (%) | 60 (64.5) | 23 (47.9) | 6 (54.5) | 12 (57.1) | 101 (58.3) |

| Ribavirin dose by weight | |||||

| 12 mg/kg or more (%) | 24 (25.8) | 20 (41.7) | 4 (36.4) | 9 (42.8) | 57 (32.9) |

| Creatinine clearance (mL/min) | 11045 | 924 | 855 | 101 | 102 |

| (range) | (53 - 261) | (46 - 167) | (60 - 111) | (41 - 203) | (41 - 261) |

| HCV RNA level | |||||

| 500 kIU/mL or more (%) | 44 (47.3) | 22 (45.8) | 4 (36.4) | 9 (42.8) | 79 (45.7) |

| Genotype 2a (%) | 67 (72.0) | 28 (58.3) | 6 (54.5) | 13 (61.9) | 114 (65.9) |

SVR was achieved by 146 (84.4 %) of 173 patients. The SVR did not differ between patients with genotypes 2a and 2b (83.1 % vs 84.6 %). The SVRs were 82.4% (14 of 17) (under 100 kIU/mL), 84.2% (16 of 19) (100-199 kIU/mL), 85.7% (24 of 28) (200 - 299 kIU/mL), 83.3% (15 of 18) (300 - 399 kIU/mL), 100% (12 of 12) (400 - 499 kIU/mL), 76.9% (10 of 13) (500 - 599 kIU/mL), 77.8% (7 of 9) (600 - 699 kIU/mL), 90.9% (10 of 11) (700-799 kIU/mL), and 82.6% (38 of 46) (800 and over kIU/mL). The SVRs were 76.9 - 100%. The SVRs of the HCV genotype 2 patients with any level of viremia level did not significantly differ.

Figure 1 shows the SVR and undetectable HCV viremia rate during the treatment of 173 patients, classified by continuation and discontinuation of combination treatment. The SVRs were significantly higher in Groups A (94.6 %) and B (89.6 %) than in Groups C (45.5 %) and D (47.6 %). A significant difference of SVR was found between patients with and without discontinuation of ribavirin (46.9 %, 15 of 32 of Groups C and D patients vs 92.9%, 131 of 141 of Groups A and B patients, P < 0.0001). During the treatment period, except for at week 4, the rates of undetectable HCV RNA were also significantly higher in Groups A and B than in Groups C and D.

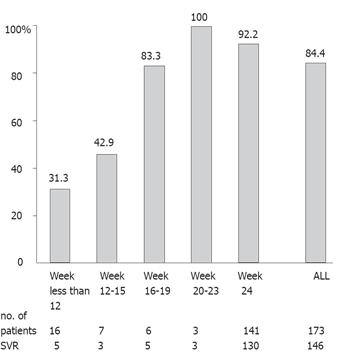

Figure 2 shows the relationship between SVR and the ribavirin treatment period in all the patients. A significant difference was found between patients with less than 16 wk of treatment period and patients with longer periods (34.8 %, 8 of 23 vs 92.0 %, 138 of 150, P < 0.0001), showing that 16 wk of ribavirin treatment significantly contributed to a SVR. Of the 173 studied patients, 104 (60.1 %) had an EVR, defined as undetectable HCV RNA within 4 wk of the start of treatment. The SVR was 94 (90.4 %) of these 104 patients with EVR, which was significantly higher than the non-EVR patients (52 of 69, 75.4 %) (P = 0.0142). No significant differences were found between patients with and without undetectable HCV RNA at 8 or 12 wk of the start of treatment. Moreover, we analyzed the relationship between SVR and the length of ribavirin treatment in the 104 patients with EVR. A significant difference was found between patients with less than 16 wk of ribavirin treatment and those with a longer treatment period (46.2%, 6 of 13 vs 96.7 %, 88 of 91, P < 0.0001). These findings showed that 16 wk of ribavirin treatment significantly contributed to a SVR, even in patients with EVR.

To assess the independent role of the IFN and ribavirin combination treatment on SVR, an adjustment by forward stepwise logistic regression analysis for all other independent risk factors identified was done. The continuation of ribavirin treatment (P < 0.0001) was significantly associated with SVR in analysis of all the patients. A higher SVR (odds ratio = 13.15) was found for patients who continued to receive ribavirin treatment than for those who discontinued it. Other factors such as sex, age, HCV genotype, pretreatment-HCV RNA level, histological findings, pretreatment platelet count and creatinine clearance, history of prior IFN, and dose reduction of IFN or ribavirin were not significantly, independently associated with a SVR.

The large number of Japanese HCV genotype 2 patients enrolled in this study was sufficient to provide for meaningful statistical analysis, even though it was retrospective. This study demonstrated that a 24-wk IFN and ribavirin combination treatment was highly effective and resulted in a remarkably high SVR (84.4 %) in genotype 2 patients, as expected. Importantly, we also showed that dose reductions of ribavirin were not associated with a poor outcome in these patients, only ribavirin discontinuation, and that the addition of ribavirin for up to 16 wk contributed to the high SVR.

In December 2004, pegylated IFN plus ribavirin combination treatment received the official approval in Japan. The combination treatment was not yet approved for clinical use for patients with chronic HCV viremia by the Japanese Ministry of Health, Labour and Welfare at the time of the present study. So far, our most effective and available treatment is the 6-month IFN-alpha plus ribavirin combination.

Remarkably high SVRs were observed for our patients with genotype 2 who took the IFN and ribavirin combination treatment. IFN monotherapy does not result in a satisfactory outcome for patients with chronic hepatitis C, particularly those with genotype 1, which is known to be IFN-resistant, whereas genotype 2 is IFN-sensitive[11-13]. The addition of ribavirin, a synthetic purine nucleoside analog, to IFN enhances the virological response[8,9,13-17]. Our research group, KULDS, also analyzed the data of patients with genotype 1 who were treated with this 24-wk combination treatment: SVR was achieved by 21% of 528 patients with genotype 1 by intention-to-treat analysis (data not published). Differences between genotype 1 and 2 patients still existed following the ribavirin combination treatment. Moreover, a striking finding in our study was that there were no differences among the patients with genotype 2 of any HCV RNA level (76.9 - 100%). The precise mechanism is unclear, although it possibly originates in different nucleotide sequence of their genome. Further study is needed to clarify the reasons for the differences in antiviral effect, by the use of novel and new tools for the quantification of the HCV replication system[19,20].

How long the ribavirin needs to be administrated to achieve the best efficacy with IFN alpha-treated patients of genotype 2 is unclear. In the present study, SVR after 16 or more weeks of treatment ranged from 83.3% to 100% and was not dependent on the dose reduction of ribavirin treatment but on the discontinuation of IFN or ribavirin treatment. A pilot study from Norway showed that patients with genotype 2 and an EVR obtained a high SVR after 14 weeks of pegylated IFN and ribavirin combination treatment[21]. The Zeuzem group also demonstrated a very high SVR in a 24-week pegylated IFN and ribavirin treatment for genotype 2 patients, and 16-week treatment duration was observed to be a significant independent predictor[17]. In view of the adverse effects, high cost of ribavirin, and the above mentioned findings along with our results, a 16-week ribavirin addition to IFN treatment would seem to produce a high rate of SVR for patients with genotype 2, especially for those with EVR, defined as undetectable HCV RNA within 4 wk of the start of the treatment.

The Davis group attempted to confirm that an EVR in patients with chronic hepatitis C undergoing initial treatment with a combination therapy of pegylated IFN alpha and ribavirin was predictive of SVR[22]. Retrospective analysis of data from other trials[23] has also suggested that patients who do not attain EVR have a nominal chance of SVR with additional weeks of treatment. While the primary goal, or “holy grail”, of treatment of chronic hepatitis C is SVR, it must be acknowledged there are other secondary goals that compel physicians to continue treatment without EVR. In fact, patients who do not achieve EVR or SVR may have histological benefit[24], leading to a decreased risk of hepatocellular carcinoma[19]. Thus, it remains to be determined whether or not early discontinuation of treatment would reduce economic costs if a long-term perspective is taken.

Several adverse reactions are associated with ribavirin. One of the most significant reactions is hemolytic problems, especially anemia[15]. Most of our patients who had to have a dose reduction or who discontinued ribavirin were observed to have anemia. It is important to reduce the dose of ribavirin at as early a stage as possible to allow the safe continuation of the combination treatment. The Nomura group pointed out that careful administration is necessary in patients over 60 years, in female patients, and in patients receiving a ribavirin dose by body weight of

12 mg/kg or more[21]. Our forward stepwise logistic regression analysis showed that the continuation of ribavirin treatment was significantly associated with SVR. This combination treatment, which could depend on hemolytic adverse reaction, has a high efficacy, if physicians are able to continue the ribavirin treatment for as short a period as 16 wk, even when taking into account of the dose reductions necessary for patients with a dangerous decrease of hemoglobin caused by ribavirin, as often seen in genotype 2 patients with a low hemoglobin level at pretreatment.

In conclusion, the 24-week IFN and ribavirin combination treatment was highly effective and resulted in a remarkably high SVR in Japanese HCV patients with genotype 2 from the retrospective study of ours. The most significant predictor was continuation of the ribavirin treatment for up to 16 wk. These findings are not pertinent to the other different genotypes.

In addition to the authors, the following investigators of the KULDS Group were involved in the present study: H Nakashima and M Murata, Haradoi Hospital, Fukuoka, K Toyoda, Yokota Hospital, Hirokawa, Fukuoka, H Takeoka, T Kuga and A Mitsutake, Mitsutake Hospital, Iki, Nagasaki, R Sugimoto, Harasanshin Hospital, Fukuoka: H Amagase and S Tominaga, Mihagino Hospital, Kitakyushu: K Yanagita, Saiseikai Karatsu Hospital, Karatsu: K Ogiwara, Kyusyu Rosai Hospital, Kitakyushu: M Tokumatsu, Saiseikai Fukuoka Hospital, Fukuoka: S Tabata, Hayashi Hospital, Fukuoka: M Yokota, National Kyushu Cancer Center, Fukuoka: H Tanaka, Chihaya Hospital, Fukuoka: S Nagase, Fukuoka Teishin Hospital, Fukuoka: S Tsuruta, Nakabaru Hospital, Fukuoka: S Tada, Moji Rosai Hospital, Kitakyushu: M Nagano, Kyushu Koseinenkin Hospital, Kitakyushu: M Honda, Nishi-Fukuoka Hospital, Fukuoka: T Umeno, Sawara Hospital, Fukuoka: T Sugimura, National Hospital Organization Fukuoka Higashi Hospital, Fukuoka: S Ueno, Kitakyushu Municipal Wakamatsu Hospital, Kitakyushu: K Miki, Kitakyushu Municipal Moji Hospital, Kitakyushu: H Okubo, Shineikai Hospital, Kitakyushu: H Fujimoto, Mitsubishikagaku Hospital, Kitakyushu: N Higuchi, Shin-Nakama Hospital, Kitakyushu: S Shigematsu, Kouseikan Hospital, Saga: N Higashi, National Hospital Organization Beppu Hospital, Beppu, Japan.

We greatly thank Hironori Ebihara, Kazukuni Kawasaki and Toshihiro Ueda for their advice for this study.

S- Editor Guo SY L- Editor Elsevier HK E- Editor Wu M

| 1. | Simmonds P, Holmes EC, Cha TA, Chan SW, McOmish F, Irvine B, Beall E, Yap PL, Kolberg J, Urdea MS. Classification of hepatitis C virus into six major genotypes and a series of subtypes by phylogenetic analysis of the NS-5 region. J Gen Virol. 1993;74:2391-2399. [PubMed] [DOI] [Cited in This Article: ] [Cited by in Crossref: 931] [Cited by in F6Publishing: 966] [Article Influence: 31.2] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 2. | Lauer GM, Walker BD. Hepatitis C virus infection. N Engl J Med. 2001;345:41-52. [PubMed] [DOI] [Cited in This Article: ] [Cited by in Crossref: 2042] [Cited by in F6Publishing: 1987] [Article Influence: 86.4] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 3. | Hoofnagle JH. Course and outcome of hepatitis C. Hepatology. 2002;36:S21-S29. [PubMed] [DOI] [Cited in This Article: ] [Cited by in Crossref: 387] [Cited by in F6Publishing: 355] [Article Influence: 16.1] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 4. | Pozzato G, Kaneko S, Moretti M, Crocè LS, Franzin F, Unoura M, Bercich L, Tiribelli C, Crovatto M, Santini G. Different genotypes of hepatitis C virus are associated with different severity of chronic liver disease. J Med Virol. 1994;43:291-296. [PubMed] [DOI] [Cited in This Article: ] [Cited by in Crossref: 101] [Cited by in F6Publishing: 103] [Article Influence: 3.4] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 5. | Hopf U, Berg T, König V, Küther S, Heuft HG, Lobeck H. Treatment of chronic hepatitis C with interferon alpha: long-term follow-up and prognostic relevance of HCV genotypes. J Hepatol. 1996;24:67-73. [PubMed] [Cited in This Article: ] |

| 6. | Neville JA, Prescott LE, Bhattacherjee V, Adams N, Pike I, Rodgers B, El-Zayadi A, Hamid S, Dusheiko GM, Saeed AA. Antigenic variation of core, NS3, and NS5 proteins among genotypes of hepatitis C virus. J Clin Microbiol. 1997;35:3062-3070. [PubMed] [Cited in This Article: ] |

| 7. | Lindsay KL, Trepo C, Heintges T, Shiffman ML, Gordon SC, Hoefs JC, Schiff ER, Goodman ZD, Laughlin M, Yao R. A randomized, double-blind trial comparing pegylated interferon alfa-2b to interferon alfa-2b as initial treatment for chronic hepatitis C. Hepatology. 2001;34:395-403. [PubMed] [DOI] [Cited in This Article: ] [Cited by in Crossref: 479] [Cited by in F6Publishing: 502] [Article Influence: 21.8] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 8. | Manns MP, McHutchison JG, Gordon SC, Rustgi VK, Shiffman M, Reindollar R, Goodman ZD, Koury K, Ling M, Albrecht JK. Peginterferon alfa-2b plus ribavirin compared with interferon alfa-2b plus ribavirin for initial treatment of chronic hepatitis C: a randomised trial. Lancet. 2001;358:958-965. [PubMed] [DOI] [Cited in This Article: ] [Cited by in Crossref: 4736] [Cited by in F6Publishing: 4508] [Article Influence: 196.0] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 9. | Wong JB, Davis GL, McHutchison JG, Manns MP, Albrecht JK. Economic and clinical effects of evaluating rapid viral response to peginterferon alfa-2b plus ribavirin for the initial treatment of chronic hepatitis C. Am J Gastroenterol. 2003;98:2354-2362. [PubMed] [DOI] [Cited in This Article: ] [Cited by in Crossref: 38] [Cited by in F6Publishing: 33] [Article Influence: 1.6] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 10. | Nomura H, Sou S, Tanimoto H, Nagahama T, Kimura Y, Hayashi J, Ishibashi H, Kashiwagi S. Short-term interferon-alfa therapy for acute hepatitis C: a randomized controlled trial. Hepatology. 2004;39:1213-1219. [PubMed] [DOI] [Cited in This Article: ] [Cited by in Crossref: 124] [Cited by in F6Publishing: 125] [Article Influence: 6.3] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 11. | Hayashi J, Kishihara Y, Ueno K, Yamaji K, Kawakami Y, Furusyo N, Sawayama Y, Kashiwagi S. Age-related response to interferon alfa treatment in women vs men with chronic hepatitis C virus infection. Arch Intern Med. 1998;158:177-181. [PubMed] [DOI] [Cited in This Article: ] [Cited by in Crossref: 76] [Cited by in F6Publishing: 71] [Article Influence: 2.7] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 12. | Furusyo N, Hayashi J, Ueno K, Sawayama Y, Kawakami Y, Kishihara Y, Kashiwagi S. Human lymphoblastoid interferon treatment for patients with hepatitis C virus-related cirrhosis. Clin Ther. 1997;19:1352-1367. [PubMed] [DOI] [Cited in This Article: ] [Cited by in Crossref: 23] [Cited by in F6Publishing: 21] [Article Influence: 0.8] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 13. | Furusyo N, Kubo N, Toyoda K, Takeoka H, Nabeshima S, Murata M, Nakamuta M, Hayashi J. Helper T cell cytokine response to ribavirin priming before combined treatment with interferon alpha and ribavirin for patients with chronic hepatitis C. Antiviral Res. 2005;67:46-54. [PubMed] [DOI] [Cited in This Article: ] [Cited by in Crossref: 22] [Cited by in F6Publishing: 20] [Article Influence: 1.1] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 14. | Poynard T, Marcellin P, Lee SS, Niederau C, Minuk GS, Ideo G, Bain V, Heathcote J, Zeuzem S, Trepo C. Randomised trial of interferon alpha2b plus ribavirin for 48 weeks or for 24 weeks versus interferon alpha2b plus placebo for 48 weeks for treatment of chronic infection with hepatitis C virus. International Hepatitis Interventional Therapy Group (IHIT). Lancet. 1998;352:1426-1432. [PubMed] [DOI] [Cited in This Article: ] [Cited by in Crossref: 1667] [Cited by in F6Publishing: 1627] [Article Influence: 62.6] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 15. | McHutchison JG, Gordon SC, Schiff ER, Shiffman ML, Lee WM, Rustgi VK, Goodman ZD, Ling MH, Cort S, Albrecht JK. Interferon alfa-2b alone or in combination with ribavirin as initial treatment for chronic hepatitis C. Hepatitis Interventional Therapy Group. N Engl J Med. 1998;339:1485-1492. [PubMed] [DOI] [Cited in This Article: ] [Cited by in Crossref: 2509] [Cited by in F6Publishing: 2416] [Article Influence: 92.9] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 16. | Dalgard O, Bjøro K, Hellum KB, Myrvang B, Ritland S, Skaug K, Raknerud N, Bell H. Treatment with pegylated interferon and ribavarin in HCV infection with genotype 2 or 3 for 14 weeks: a pilot study. Hepatology. 2004;40:1260-1265. [PubMed] [DOI] [Cited in This Article: ] [Cited by in Crossref: 240] [Cited by in F6Publishing: 247] [Article Influence: 12.4] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 17. | Zeuzem S, Hultcrantz R, Bourliere M, Goeser T, Marcellin P, Sanchez-Tapias J, Sarrazin C, Harvey J, Brass C, Albrecht J. Peginterferon alfa-2b plus ribavirin for treatment of chronic hepatitis C in previously untreated patients infected with HCV genotypes 2 or 3. J Hepatol. 2004;40:993-999. [PubMed] [DOI] [Cited in This Article: ] |

| 18. | Hayashi J, Kishihara Y, Yamaji K, Yoshimura E, Kawakami Y, Akazawa K, Kashiwagi S. Transmission of hepatitis C virus by health care workers in a rural area of Japan. Am J Gastroenterol. 1995;90:794-799. [PubMed] [Cited in This Article: ] |

| 19. | Lohmann V, Körner F, Koch J, Herian U, Theilmann L, Bartenschlager R. Replication of subgenomic hepatitis C virus RNAs in a hepatoma cell line. Science. 1999;285:110-113. [PubMed] [DOI] [Cited in This Article: ] [Cited by in Crossref: 2294] [Cited by in F6Publishing: 2224] [Article Influence: 89.0] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 20. | Kato T, Date T, Miyamoto M, Furusaka A, Tokushige K, Mizokami M, Wakita T. Efficient replication of the genotype 2a hepatitis C virus subgenomic replicon. Gastroenterology. 2003;125:1808-1817. [PubMed] [DOI] [Cited in This Article: ] [Cited by in Crossref: 487] [Cited by in F6Publishing: 470] [Article Influence: 22.4] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 21. | Nomura H, Tanimoto H, Kajiwara E, Shimono J, Maruyama T, Yamashita N, Nagano M, Higashi M, Mukai T, Matsui Y. Factors contributing to ribavirin-induced anemia. J Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2004;19:1312-1317. [PubMed] [DOI] [Cited in This Article: ] [Cited by in Crossref: 64] [Cited by in F6Publishing: 51] [Article Influence: 2.6] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 22. | Davis GL, Wong JB, McHutchison JG, Manns MP, Harvey J, Albrecht J. Early virologic response to treatment with peginterferon alfa-2b plus ribavirin in patients with chronic hepatitis C. Hepatology. 2003;38:645-652. [PubMed] [DOI] [Cited in This Article: ] [Cited by in Crossref: 596] [Cited by in F6Publishing: 568] [Article Influence: 27.0] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 23. | Fried MW, Shiffman ML, Reddy KR, Smith C, Marinos G, Gonçales FL, Häussinger D, Diago M, Carosi G, Dhumeaux D. Peginterferon alfa-2a plus ribavirin for chronic hepatitis C virus infection. N Engl J Med. 2002;347:975-982. [PubMed] [DOI] [Cited in This Article: ] [Cited by in Crossref: 4847] [Cited by in F6Publishing: 4689] [Article Influence: 213.1] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 24. | Poynard T, McHutchison J, Davis GL, Esteban-Mur R, Goodman Z, Bedossa P, Albrecht J. Impact of interferon alfa-2b and ribavirin on progression of liver fibrosis in patients with chronic hepatitis C. Hepatology. 2000;32:1131-1137. [PubMed] [DOI] [Cited in This Article: ] [Cited by in Crossref: 209] [Cited by in F6Publishing: 221] [Article Influence: 9.2] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |