Published online Feb 21, 2008. doi: 10.3748/wjg.14.1141

Revised: December 3, 2007

Published online: February 21, 2008

Trichobezoar is a rare intriguing disorder in which swallowed hairs accumulates in the stomach. Being indigestible and slippery, it could not be propulsed and becomes entrapped within the stomach. Large amounts can thus accumulate over the years forming a hair ball. Rapunzel syndrome is a variant where hair accumulation reaches the small gut and beyond in some cases. Although the syndrome has been known for many years, only 24 cases have been reported in the literature and the discovery of a new case is always surprising. In this report, we present two cases discovered within a period of three months. One of them was pregnant and had small bowel intussusception and perforation, a very rare combination. We hereby add two more cases to the literature. To our knowledge, this is the first report on two cases of Rapunzel syndrome, the diagnosis of which demands a high index of suspicion.

- Citation: Rabie ME, Arishi AR, Khan A, Ageely H, El-Nasr GAS, Fagihi M. Rapunzel syndrome: The unsuspected culprit. World J Gastroenterol 2008; 14(7): 1141-1143

- URL: https://www.wjgnet.com/1007-9327/full/v14/i7/1141.htm

- DOI: https://dx.doi.org/10.3748/wjg.14.1141

Reported in the 18th century[1], trichobezoar is a com-bination of “trich” meaning hair in Greek and “bezoar” meaning poison antidote in Arabic or Persian[2]. The habitual swallowing of hairs over the years leads to the formation of a hair ball in the stomach. Extension of hairs beyond the stomach into the small bowel in the form of a tail has been termed Rapunzel syndrome[3], after Rapunzel, the heroine of a German fairy tale[4].

An 11-year-old female, was referred with an abdominal mass associated with epigastric pain, sense of fullness and vomiting after meals, for the previous 15 days. She was a poor school performer and had a history of pica (habitual ingestion of foreign bodies) and habitual thumb sucking. Her siblings, two brothers and two sisters, were all healthy and she had no family or social strains.

On examination, she was uncooperative and mildly dehydrated. Her temperature was 37°C, blood pressure 110/60 mmHg and pulse 90/min. The chest and heart examination were normal. Abdominal examination showed a firm mass about 8 cm × 10 cm in the epigastrium.

Her white blood cell count was 12 800/&mgr;L (reference range 4000-10 000), Hb 12.9 g/dL (reference range 12.1-15.1), platelet count 574 000/&mgr;L (reference range 190 000-405 000). The rest of laboratory investigations showed serum proteins of 6.6 g/dL (reference range 6.4-8.2) and serum albumin of 2.7 g/dL (reference range 3.4-5.0). There was no electrolyte disturbance and liver functions, serum amylase and lipase were normal.

Computed axial tomography showed a mass with a hazy outline, filling the stomach. There were air pockets and the mass showed no contrast enhancement. So, the patient was prepared for surgery.

During surgery, a hair ball was found occupying the whole stomach (Figure 1A and B) and extending as far down as the jejunum. By gentle manipulation, it was extracted intact (Figure 2), and a gastric ulcer was also found (Figure 3).

After operation, the patient convalesced well, and her hospital stay was uneventful. She was discharged for follow-up in the Paediatric Psychiatry Clinic.

A 19-year-old primigravida, at the end of the second trimester, was referred with upper abdominal pain, greenish vomiting, constipation and abdominal distension, for five days. Her history was positive for anorexia and failure to gain weight since childhood. There were no other medical or psychiatric problems.

On examination, the patient was cachectic and dehydrated, her blood pressure was 120/70 mmHg, pulse 105/min, and temperature 36.8°C. The chest and heart examination were normal.

Abdominal examination revealed a well defined, smooth and firm mass, 18 cm × 20 cm, occupying the epigastrium and almost both hypochondria. The mass was resonant to percussion and moved freely with breathing.

Her white blood cell count was 5400/&mgr;L (reference range 4000-10 000), Hb 9.2 g/dL (reference range 12.1-15.1), platelet count 260 000/&mgr;L (reference range 190 000-405 000), Na 138 mEq/L (reference range 135-153), K 2.4 mEq/L (reference range 3.5-5.3). Her random blood sugar, renal values, liver function tests, serum lipase and amylase were within the normal range.

Abdominal ultrasound showed a large epigastric mass, with acoustic shadow suggestive of a calcified margin. Upper endoscopy disclosed the nature of the mass as a large hair ball occupying the whole stmoch, and the patient was posted for surgery.

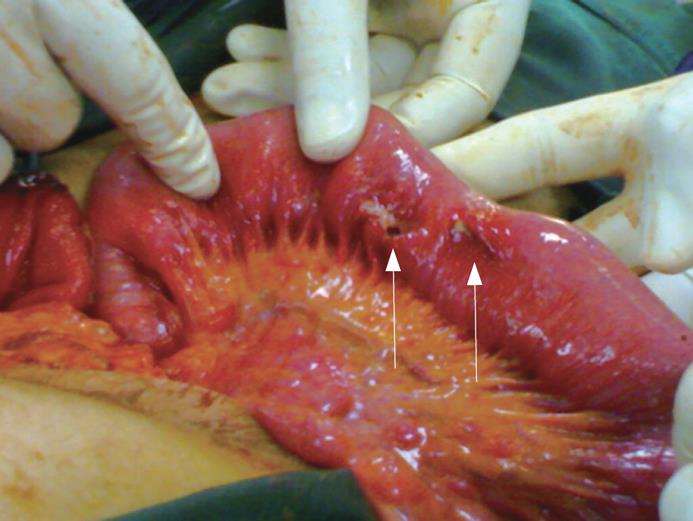

At operation, a gastrotomy was done and the hair ball was found extending down to the upper jejunum, causing jejuno-jejunal intussusception. The intussusception was reduced and the hair ball was manipulated out. Two jejunal necrotic perforations were found at the mesenteric border necessitating resection (Figure 4). The gastrotomy was closed in two layers and the abdomen was closed with drainage.

The recovery period was complicated by foetal loss, wound infection and limited ability to receive enough oral feeds. A psychiatric evaluation diagnosed her having an adjustment disorder. The patient finally recovered well and was discharged for psychiatric follow-up.

Trichobezoar was first reported in 1779 by Baudamant[1]. The word is a combination of “trich” and “bezoar”, with the former meaning hair in Greek, and the later meaning poison antidote in Arabic or Persian[2]. By necessity, trichotillomania (plucking of hairs) and trichophagia (swallowing of hairs) are the leading events.

Rapunzel syndrome, described first by Vaughan and colleagues in 1968[3], is an extension of the gastric trichobezoar into the small gut in the form of a long tail. It is named after Rapunzel, the heroine of a German fairy tale by the Grimm brothers. She used to let her long golden hair tress down the tower where she was imprisoned, to allow her prince lover to climb up.

The syndrome has been rarely reported. In their report in 1999, Dalshaug and colleagues found only 11 cases[4], whereas in a recent search in 2007, only 24 cases were retrieved from the literature[5].

The reason why hair collects in the stomach is not fully understood. Debakey and Oschner suggested that hair entrapment in the gastric folds is the initiating event[6]. Due to its indigestibility, resilience and slippery nature, it becomes entrapped within the mucosal folds where it gets enmeshed, and acquires more hairs and thus a larger size.

The clinical picture ranges from abdominal pain, nausea, vomiting, early satiety and weight loss, to bleeding ulcer, intestinal obstruction and perforation. Intussusception has also been reported[4].

Although a psychiatric trouble is usually present[7], this is not always the case as the syndrome may affect healthy women[8]. In the first case reported here, the patient had a history of pica, which should be an alarming sign, mandating behavioural or psychiatric intervention. In the second case, although the patient denied any psychiatric troubles or social strains, on careful enquiry, her husband revealed that she had the habit of putting hair in her mouth while thinking.

Anaemia and hypoalbuminaemia associated with chronic gastritis usually go unnoticed until the case is brought to light by the onset of severer complications such as hemorrhage, enteric or pancreatic or biliary obstruction. The onset of perforation and peritonitis is largely responsible for an attendant mortality of about 30%[9]. In the second case, it was evident that intestinal perforation was a very recent onset as the patient showed no relevant signs on initial evaluation.

Trichobezoar affects young females almost exclusively[9] and it has been previously reported during pregnancy[10]. The presence of pregnancy may complicate the management, and foetal loss, as occurred in our second patient, is always a possibility. Provided there is no eminent danger, it might be wise to postpone intervention till the patient delivers.

As mentioned in the classic series of Debakey et al[6], an upper abdominal mass remains the commonest presenting sign. In our cases, an upper abdominal mass was easily visible due to its large size and the cachectic habitus of the patients.

Diagnostic modalities include US, CT scan and upper endoscopy. CT scan has a high accuracy rate, but the accuracy of US in such cases is not so high[12]. On CT scan, a well-circumscribed lesion, composed of concentric whorls of different densities with pockets of air enmeshed within it, appears in the region of stomach. Oral contrast fills the more peripheral interstices of the lesion and a thin band of contrast circumscribes it. Absence of significant post intravenous contrast enhancement precludes a neoplastic lesion[13]. In our second case, US failed to give the correct diagnosis, and as CT scan was not an option due to the presence of pregnancy, upper endoscopy was needed to reach the diagnosis. Endoscopy has also been reported to have a therapeutic potential[11]. It is probable that US is not the modality of choice in such conditions[1112].

Laparoscopy may be successful in extracting the hair ball[1014]. In our cases, this would not be an easy undertaking due to the young age of the first case and the presence of intussusception and pregnancy in the second. Other minimally invasive modalities like extracorporeal lithotripter, endoscopic lithotripter, and laser fragmentation[9] are emerging. Their role and success rates need to be defined and open surgery remains the gold standard.

In conclusion, surgeons, physicians, and radiologists should consider trichobezoar in the differential diagnosis of gastrointestinal obstruction in young females, especially in the presence of an upper abdominal mass. Timely diagnosis and treatment are of utmost importance to avoid a possible fatal outcome. As recurrences are known, each patient should have a proper psychiatric evaluation and follow-up.

| 1. | Baudamant WW. Memoire sur des cheveux trouves dans l’estomac et dans les intestines grêles. J Med Chir Pharm. 1779;52:507-514. [Cited in This Article: ] |

| 2. | Williams RS. The fascinating history of bezoars. Med J Aust. 1986;145:613-614. [Cited in This Article: ] |

| 3. | Vaughan ED Jr, Sawyers JL, Scott HW Jr. The Rapunzel syndrome. An unusual complication of intestinal bezoar. Surgery. 1968;63:339-343. [Cited in This Article: ] |

| 4. | Dalshaug GB, Wainer S, Hollaar GL. The Rapunzel syndrome (trichobezoar) causing atypical intussusception in a child: a case report. J Pediatr Surg. 1999;34:479-480. [Cited in This Article: ] |

| 5. | Naik S, Gupta V, Naik S, Rangole A, Chaudhary AK, Jain P, Sharma AK. Rapunzel syndrome reviewed and redefined. Dig Surg. 2007;24:157-161. [Cited in This Article: ] |

| 6. | Debakey M, Oschner A. Bezoars and concretions: Comprehensive review of literature with analysis of 303 collected cases and presetitations of 8 additional cases. Surgery. 1939;5:132-160. [Cited in This Article: ] |

| 7. | Salaam K, Carr J, Grewal H, Sholevar E, Baron D. Untreated trichotillomania and trichophagia: surgical emergency in a teenage girl. Psychosomatics. 2005;46:362-366. [Cited in This Article: ] |

| 8. | Coulter R, Antony MT, Bhuta P, Memon MA. Large gastric trichobezoar in a normal healthy woman: case report and review of pertinent literature. South Med J. 2005;98:1042-1044. [Cited in This Article: ] |

| 9. | Phillips MR, Zaheer S, Drugas GT. Gastric trichobezoar: case report and literature review. Mayo Clin Proc. 1998;73:653-656. [Cited in This Article: ] |

| 10. | Meyer-Rochow GY, Grunewald B. Laparoscopic removal of a gastric trichobezoar in a pregnant woman. Surg Laparosc Endosc Percutan Tech. 2007;17:129-132. [Cited in This Article: ] |

| 11. | Kuroki Y, Otagiri S, Sakamoto T, Tsukada K, Tanaka M. Case report of trichobezoar causing gastric perforation. Digestive Endoscopy. 2000;12:181-185. [Cited in This Article: ] |

| 12. | Sharma Y, Chhetri RK, Makaju RK, Chapagain S, Shrestha R. Epigastric mass in a young girl: trichobezoar. Imaging diagnosis. Nepal Med Coll J. 2006;8:211-212. [Cited in This Article: ] |

| 13. | Morris B, Shah ZK, Shah P. An intragastric trichobezoar: computerised tomographic appearance. J Postgrad Med. 2000;46:94-95. [Cited in This Article: ] |

| 14. | Sharma UK, Sharma Y, Chhetri RK, Makaju RK, Chapagain S, Shrestha R. Epigastric mass in a young girl: trichobezoar. Imaging diagnosis. Nepal Med Coll J. 2006;8:211-212. [Cited in This Article: ] |