Published online Aug 21, 2008. doi: 10.3748/wjg.14.4968

Revised: July 14, 2008

Accepted: July 21, 2008

Published online: August 21, 2008

Primary malignant melanoma of the liver is an exceedingly rare tumor. Only 12 cases have been reported in the worldwide literature. We present a case of isolated malignant melanoma of the liver occurring in a 36-year-old Chinese male patient. Comprehensive dermatologic and ophthalmologic examinations revealed no evidence of a cutaneous or ocular primary lesion. Other lesions in brain, respiratory tract, lung, gastrointestinal tract and anus, were not demonstrated by serial position emission tomography (PET). Microscopic examination of the resected specimen revealed a malignant melanoma, which was confirmed by immunohistochemical staining for HMB-45, S-100 protein, melanoma-pan and vimentin. Moreover, electron microscopy demonstrated melanosomes in tumor cell cytoplasm. Our case shows that primary malignant melanoma may occur in the liver and should be considered when the histopathological appearance is not typical for other hepatic neoplasm.

- Citation: Gong L, Li YH, Zhao JY, Wang XX, Zhu SJ, Zhang W. Primary malignant melanoma of the liver: A case report. World J Gastroenterol 2008; 14(31): 4968-4971

- URL: https://www.wjgnet.com/1007-9327/full/v14/i31/4968.htm

- DOI: https://dx.doi.org/10.3748/wjg.14.4968

Malignant melanoma occurs most frequently in skin but also in many organs and tissues of the body. However, primary hepatic malignant melanoma is exceedingly rare. Only 12 cases, including 8 cases from PubMed and 4 cases from Chinese literature[1-4], have been reported. In PubMed, there are only 3 cases of definite primary melanoma[5-7]. Microscopically, it may be easily misdiagnosed because of morphological heterogeneity and hypomelanotic appearance. The present case represents the only case encountered in our department. In this report, we describe our pathological observations and review the literature in order to improve our understanding of the disease, avoid misdiagnosis and provide evidence for its clinical treatment and prognosis.

A 36-year-old man was admitted to the Department of General Surgery, Tangdu Hospital, Fourth Military Medical University (Xi’an, Shaanxi Province, China) because a mass in his liver was found 4 d ago at a routine health check. He had no history of alcohol abuse or hepatitis. No record of hepatocellular carcinoma (HCC) or any hereditary disease was found in his family members. Routine clinical biochemistry showed normal levels of aspartate aminotransferase (AST), alanine aminotransferase (ALT), lactate dehydrogenase (LDH), γ-glutamyltransferase (γ-GTP), α-fetoprotein (AFP) and plasma proteins. Laboratory tests failed to show any positive hepatitis B surface antigen (HBsAg) or anti-hepatitis C virus (HCV) antibody. Contrast-enhanced abdominal computerized tomography (CT) displayed a 10.1 cm × 12.8 cm well-defined hepatic mass in the right-posterior lobe of the liver without evidence for spread to neighboring lymph nodes or abdominal dropsy (Figure 1). The resected fresh tissue was fixed in 40 g/L formaldehyde solution, embedded in paraffin. Sections of 4 μm in thickness were prepared and stained with hematoxylin and eosin (HE). Immunostaining was carried out using a streptavidin-labeled peroxidase (S-P) kit (KIT9730) according to its manufacturer’s instructions. Primary antibodies used in this study included those against HMB-45, melanoma-pan, epithelial membrane antigen (EMA), carcinoembryonic antigen (CEA), cytokeratins (18, 19, 7, 8), high-MW-CK, chromogranin A (CgA), synaptophysin (syn), sesmin, nerve specificity enolase (NSE), smooth muscle actin (SM-actin), vimentin, CD34, AFP, S-100 protein, CD117, human chorionic gonadotrophin (HCG), leucocyte common antigen (LCA), HBsAg, hepatitis B core antigen (HBcAg), as well as anti-HCV antibody. All of the reagents for immunostaining were supplied by Maxim Biotechnology Corporation Ltd, Fuzhou, China.

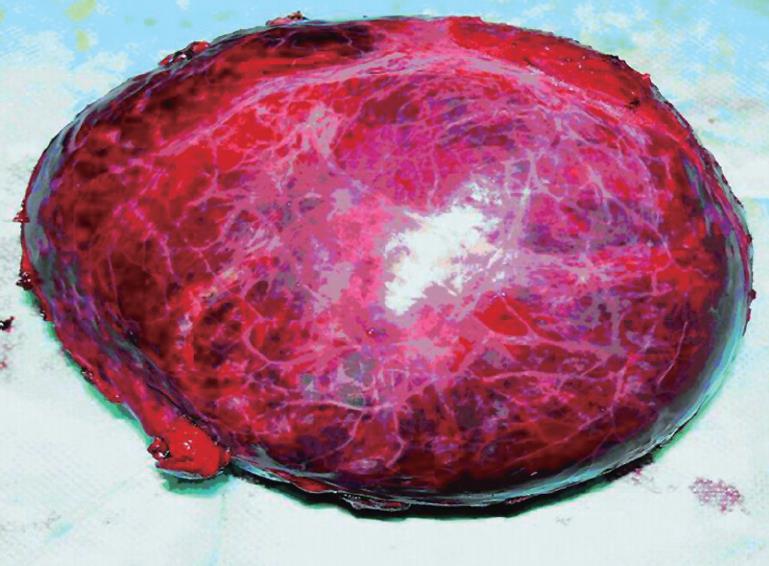

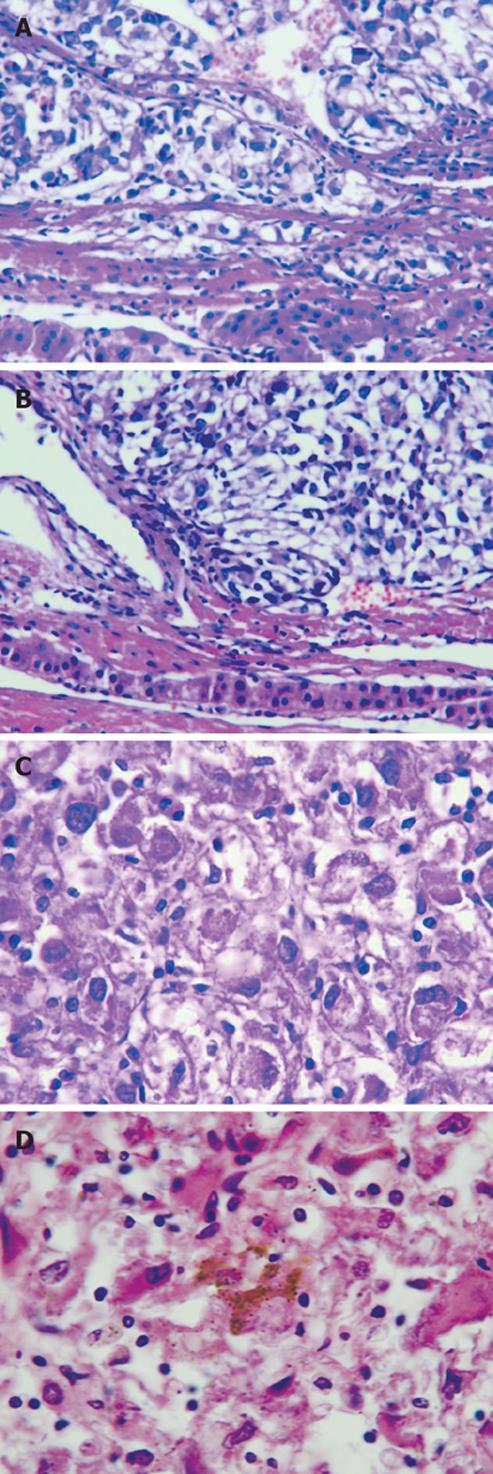

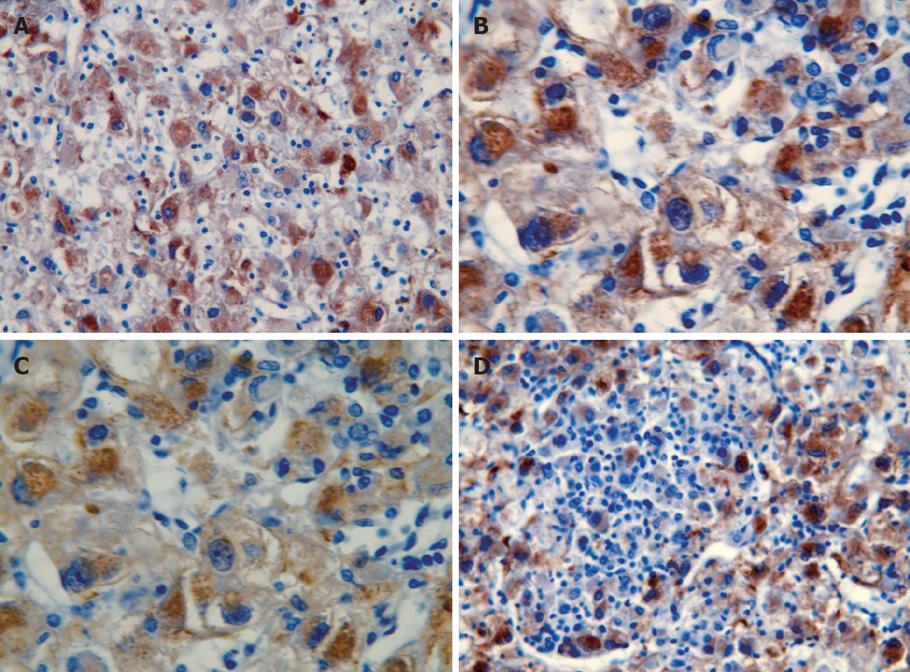

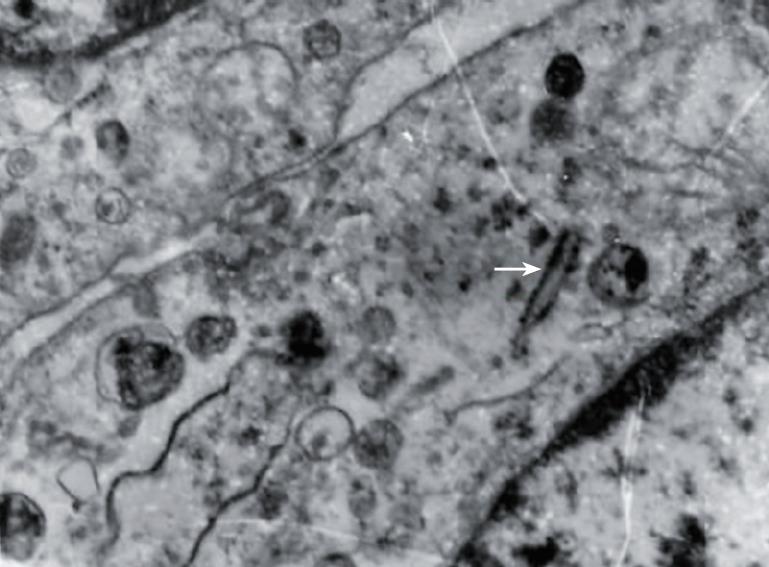

Grossly, the resected mass measured 12 cm × 11 cm × 6 cm (Figure 2). There was a clear differentiation between the mass and its surrounding normal tissue, and the cut surface of the tumor was grayish-yellow in color. Microscopically, the tumor cells showed a diffuse infiltration, and fibrous tissue could be observed between the lesion and normal hepatocytes. A few tumor cells breaking through the capsule infiltrated the adjacent liver tissue (Figure 3A and B). The tumor cells were pleomorphic, with round, spindle-shaped and irregular morphologies. The tumor cell nuclei were round or oval, and the nucleoli were prominent, with both eosinophilic and basophilic varieties observed (Figure 3C). Some tumor cells contained melanin deposition (Figure 3D). Immunohistochemically, the tumor cells were positive for vimentin (Figure 4A), melanoma-pan (Figure 4B), HMB-45 (Figure 4C) and S-100 protein (Figure 4D), but did not display AFP, high-MW-CK, CK18, CEA, CK19, CD34, CD117, NSE, LCA, CgA, HCG, EMA, desmin, SM-actin, SC-actin, myoglobin and immunoreactivity. Electron microscopy revealed occasional melanosomes in cytoplasm (Figure 5).

The complete absence of evidence for any cutaneous, ocular, mucosal lesions in all organs examined by serial position emission tomography (PET) supported the final diagnosis of primary melanoma.

After a wide local surgical resection, the patient received a 4-wk immunomodulatory therapy at a high dose of IV interferon alpha-2b, once a day. He then received a lower dose subcutaneous regimen, three times a week for a further 9 wk. This regimen was well-tolerated. He was regularly followed up. Three months after operation, he had no recurrence of the disease. However, recurrent foci were found 5 mo after operation.

Melanoma is a melanin-induced malignant tumor, most prevalent in patients over the age of 30 years. It mainly occurs in skin, but may be found in retina, anorectal canal, genital tract, gastrointestinal (GI) tract, accessory nasal cavity and parotid. Non-cutaneous primary melanomas carry a particularly high mortality because of their propensity for dissemination and invasion, often before they are clinically apparent.

Primary malignant melanoma of the liver is an extremely rare non-epithelial neoplasm, and few cases have been reported. We thus summarize, in this paper, the clinical characteristics and histopathologic manifestations of this unusual tumor.

Malignant melanomas of the skin originate from epidermal melanocytes or neural cells, both are derived from neural crest precursors[8]. Several factors, including race, heredity, tissue injury, stimulation, viral infection, sun-exposure and immunization, can lead to malignant transformation[9]. The origin of mucosal malignant melanoma is unclear. Most experts hold that malignant melanomas of non sun-exposed tissues are linked to stimulation by the blood-borne sunlight circulation factor, expressed in sun-exposed melanoblasts[10]. Based on the origin of primary melanomas of the esophagus and stomach, some authors believe that these alimentary tract neoplasms originate from migrating melanocytes invaginated by digestive tract epithelial cells during embryogenesis[11,12], which is supported by the distribution of melanocytes in other typically-occurring mucosal cells of the rectum[13]. However, the origin and pathogenesis of primary melanomas arising in parenchymal organs are still unclear.

It is difficult to show the clinical characteristics of primary hepatic malignant melanoma because case reports are available prior to the 1970s, except for 5 Chinese patients (2 males and 3 females, mean age 42.2 years, range 27-60 years). Previously reported patients had no readily identifiable risk factors when compared to patients with primary HCC.

Pathologically, hepatic malignant melanoma resembles that of the skin or mucosa, exhibiting morphologic variability within the tumor sample. Microscopically, the tumor mass is comprised of epithelioid cells arranged in nests, or spindle cells arranged in fascicles, with or without melanin pigment deposition. Mitotic figures are readily apparent. However, our case suggests that it may be difficult to identify malignant melanoma from a biopsy sample in some cases, because portions of the tumor may be amelanotic. In these cases, ancillary immunohistochemical staining may be extremely valuable[14]. In our case, when specimens of HCC, haemangioma, large-B cell lymphoma, smooth muscle tumor and rhabdomyosarcoma were all considered in the differential diagnosis, all of which were potentially consistent with the inact capsule, large size, and well-circumscribed boundaries. However, all the above tumors could be ultimately excluded based on their histopathologic characteristics and immunohistochemical staining. After reviewing a number of additional sections and detecting sporadic pigment granules in the tumor cytoplasm, we considered a diagnosis of malignant melanoma. The tumor cells expressed HMB45, S-100 protein, vimentin and melanoma-pan, all of which were consistent with hepatic melanoma. Our preliminary diagnosis was then confirmed by electron microscopy.

Once the pathologic diagnosis was established, whether the tumor was a primary or secondary lesion should be considered. An extensive investigation of potential primary sites demonstrated no evidence for hepatic melanoma, suggesting that the tumor is a primary melanoma of the liver.

Given the rarity of this tumor, the optimal therapeutic regimen is not known. In fact, the natural history of these cases also remains unclear. Since surgical therapy is usually palliative, a more aggressive oncologic regimen consisting of chemotherapy, immunotherapy and radiotherapy may be required. With the natural history largely unknown, it is necessary to find treatment modalities for other deep primary melanomas,

Peer reviewers: Gianluigi Giannelli, MD, Dipartimento di Clinica Medica, Immunologia e Malattie Infettive, Sezione di Medicina Interna, Policlinico, Piazza G Cesare 11, Bari 70124, Italy; Jose JG Marin, Professor, Department of Physiology and Pharmacology, University of Salamanca, CIBERehd, Campus Miguel de Unamuno, ED-S09, Salamanca 37007, Spain; Xin Chen, Professor, University of California, San Francisco, 513 Parnassus Ave. S-816, Box 0912, San Francisco 94143, United States

S- Editor Li DL L- Editor Wang XL E- Editor Ma WH

| 1. | Hu XR. A case of primary malignant melanoma of the liver. Zhonghua Fangshexue Zazhi. 2006;40:1115. [Cited in This Article: ] |

| 2. | Li HC, Xu HB, Wang HM. A case of malignant melanoma of the liver showing a enormous cystic occupy. Zhonghua Zhongliu Zazhi. 2003;25:110. [Cited in This Article: ] |

| 3. | Wang CF, An DJ, Zhang C. A case of primary malignant melanoma of the liver. Zhonghua Gandanyi Waike Zazhi. 2005;11:480. [Cited in This Article: ] |

| 4. | Zhang H, Zhao JM. Primary enormous malignant melanoma of the liver: a case report. Zhongguo Yike Daxue Xuebao. 1995;24:93. [Cited in This Article: ] |

| 5. | Boj E. [Case of primary malignant melanoma of the liver according to world literature; review and critical evaluation of cases of primary malignant pigmented tumors of the liver.]. Patol Pol. 1954;5:17-24. [Cited in This Article: ] |

| 6. | Furuta M, Suto H, Nakamoto S, Suzuki R, Hirai Y, Asanuma K. MRI of malignant melanoma of liver. Radiat Med. 1995;13:143-145. [Cited in This Article: ] |

| 7. | Tacquet A, Clay A, Guerrin F, Demaille A. [Case of probable primary melanoma of the liver.]. Arch Mal Appar Dig Mal Nutr. 1959;48:89-92. [Cited in This Article: ] |

| 8. | Liu TH. Diagnostic Pathology. Beijing: People publishing company 1994; 983-985. [Cited in This Article: ] |

| 9. | Yu CP, Zhao TE. The study and development of malignant melanoma. Shiyong Yiyuan Linchuang Zazhi. 2006;3:51. [Cited in This Article: ] |

| 10. | Takubo K, Kanda Y, Ishii M, Nonose N, Saida T, Fujita K, Nakagawa H, Fujiwara M. Primary malignant melanoma of the esophagus. Hum Pathol. 1983;14:727-730. [Cited in This Article: ] |

| 11. | Alberti JE, Bodor J, Torres AD, Pini N. [Primary malignant melanoma of the esophagus associated with melanosis of the esophagus and stomach]. Acta Gastroenterol Latinoam. 1984;14:139-148. [Cited in This Article: ] |

| 12. | De La Pava S, Nigogosyan G, Pickren JW, Cabrera A. Melanosis of the esophagus. Cancer. 1963;16:48-50. [Cited in This Article: ] |

| 13. | Clemmensen OJ, Fenger C. Melanocytes in the anal canal epithelium. Histopathology. 1991;18:237-241. [Cited in This Article: ] |

| 14. | Chang F, Deere H. Esophageal melanocytosis morphologic features and review of the literature. Arch Pathol Lab Med. 2006;130:552-557. [Cited in This Article: ] |