Fuel for Dominance

Summary

Excerpt

Table Of Contents

- Cover

- Title

- Copyright

- About the editor

- About the book

- This eBook can be cited

- Translator

- List of Contents

- Chapter 1 Theoretical Background

- People’s Republic of China

- Chapter 2 China as a Re-emerging Power

- Chapter 3 China’s Geoeconomics

- Chapter 4 China’s Monetary Power: Internationalization of Yuan as an Example of PRC’s Geoeconomic Strategy

- Europe

- Chapter 5 The German Paradox: A European Economic or Political Power?

- Chapter 6 Development of Defense Policy and Armaments Industry in the European Union

- Chapter 7 The Climate and Energy Policy of the European Union As Fuel for Political and Economic Dominance

- Chapter 8 The Energy Policy of Russia, or the Energy Basis of Geopolitical Supremacy

- United States of America

- Chapter 9 Bretton Woods as an Economic Regime

- Chapter 10 The Energy Sector as an Instrument of Power of the United States in the 21st Century

- Chapter 11 The USA Policy on the Development of Military Technologies

- Chapter 12 Conclusion

- Bibliography

- Biographical notes

- Series index

Tomasz Grzegorz Grosse

Chapter 1 Theoretical Background

Abstract: The introductory part of this chapter presents two notions that are fundamental for the whole volume, namely geopolitics and geoeconomics. The author highlights the ways in which these notions are defined in the literature on the subject, presents the terminological interpretations he has chosen as well as geoeconomic instruments and endowments. Then he proceeds to discussing theoretical foundations taking into account three main schools analyzing the role of the state in the economy, namely (1) liberalism, (2) Marxism and close to (3) realism – statism, mercantilism and concepts of the developmental state. Both the definitions and further presentations constitute the key to the later discussion over the analysis of examples illustrating the selected economic policies that exist in the European Union and are implemented by global or regional powers. In the summary, the author identifies the common objectives for all the chapters in the volume.

Keywords: geopolitics, geoeconomics, theoretical foundations, economic regime

Introduction

Primarily, this book aims to show the economic basis for power in international relations using selected examples. In this context, power is understood by me as an attempt to increase political influence over other actors or to gain more autonomy from external actors and excessive influence from particular internal interests. Economic policy instruments provide the basis for power in foreign policy. The economy is one of the most important components of power. It can be vividly described as a fuel for achieving strategic goals. Although economic exchange usually brings benefits to all stakeholders, it may also be asymmetric, i.e., unevenly distributed to the participating parties. If such asymmetry persists over a long period of time and is not counterbalanced by commercial exchange in other areas, it may have structural consequences as it may lead to disproportionate increases in benefits for one party and higher costs for the other. The effects of such an economic exchange usually have political consequences. Indeed, economic advantages can lead to dependence of weaker players and dominance of stronger ones. Thus, the two spheres of geopolitics and economics permeate each other.

←9 | 10→In the introductory part of this chapter, I will present two basic terms: geopolitics and geoeconomics.1 It is my intention to highlight the ways in which these terms are defined in the literature on the subject as well as to present the terminological interpretations I have chosen. This also applies to the theoretical foundations adopted herein. They constitute the key to the later analysis of examples illustrating the selected economic policies that exist in the European Union (EU) and are implemented by global or regional powers.

What is geopolitics?

As a notion, geopolitics appeared in social sciences in the 19th century. Its interpretations refer to two main schools of international relations: realism and liberalism. In classical terms, i.e., from the perspective of the 19th century, geopolitics is understood as a rivalry of great powers for dominance and territory or for power in the geographical dimension.2 It is an interpretation close to the realistic school in international relations.

The interpretation focuses on the largest countries that are central to the shaping of international governance and also focuses on the external conditions of this rivalry, i.e., relations between individual powers and less on the internal conditions prevailing in individual countries. An important assumption of a realistic school is the conviction that there are “objective” geopolitical interests, which can also be defined as the Raison d’État (the reason of the state) of a given country. It is the consequence of external structural and geographical factors on the international scene. Internal conditions – in terms of realism – may be important only in the context of forming the potential of a given country, but not for example for the shaping of “subjective” interpretations of geopolitical interests.

←10 | 11→Scholars point to the successive stages of conducting geopolitical analyses.3 In the first half of the 19th century it was focused on rivalry (or cooperation) between the main European powers, which held a central position in the then international order. At the same time, it included the colonial expansion of these powers and the exploitation of peripheral areas as important sources of their power. Hence, the main geopolitical division was the civilizational criterion separating the European center from the peripheries. In the mid-19th century, at a time when nation states were becoming stronger and nationalism was flourishing, the main geopolitical divisions concerned, on the one hand, the individual European powers and, on the other hand, the distinction between civilized Europe and subordinate and exploited regions of the world.4 This approach culminated in the 1930s and then in the Second World War. Later on, the main geopolitical division was marked by ideological differences between the capitalist and democratic West and the block of communist countries.5

What was highlighted in the aftermath of the classical geopolitical analysis was the role of national political community. Raison d’État or the geopolitical interest of a particular state was being related to the whole community, and thus not to particular individual or group interests.6 It was also not understood as the aggregation of partial interests at the national level. The geopolitical interest of the state (and of a given political community) was primarily the result of external conditions. This is an important feature of the realistic approach, which contrasts with the interpretation offered by the liberal school.

In liberal terms, internal conditions, including dominant political ideas as well as political deliberations concerning the interpretation of the strategic situation, are of great importance for the formation of interests. The final assessment of geopolitical interests is therefore not “objective” and does not only serve as a derivative of external conditions. It is rather the result of pressure from the most ←11 | 12→influential economic and social interests or the result of a public debate on the foreign policy of a given country. A liberal approach to geopolitics is linked to a “God’s eye view of the world,”7 i.e., to the dominating political ideology or political paradigm that exists in a given community. It focuses on the “grand strategy” and the mechanisms for its implementation in internal politics. Admittedly, the aforementioned strategy is shaped in relation to a specific international situation, including geographical conditions.8 However, for liberals, the territorial context and the international situation are not always decisive for the interpretation of geopolitical interests. Sometimes, in the theoretical approach discussed here, the main role is played by completely different conditions, e.g. social, economic or ideological. This is the case with feminist and alter globalist geopolitics.9 Moreover, an additional argument of liberals is the thesis regarding the importance of global economic and political interdependencies which weaken the earlier significance of geography (and thus the classical understanding of geopolitics).

The liberal approach also revisits historical examples of classical geopolitics. It recognizes, among other things, that in the 19th century the geopolitical goal of national elites was not only to gain advantage in international relations, but also to strengthen potential and internal structures of given state. This included reinforcing the national economy and other resources that had military applications. This also included the consolidation of society within state structures, based, among other things, on nationalist ideology. The “building of a nation,” i.e., a stable and integrated political community within a given great power, had a great significance for its geopolitical power on the international arena. In addition to nationalist ideas, these efforts could include the promotion of democracy, civil rights and social privileges (initially for soldiers and their families and war veterans, but later also for all other citizens). Hence the term “social geopolitics” to highlight these processes.10

In the conclusion to these considerations it is worthwhile to present the so-called critical geopolitics, which is most often connected with the Marxist ←12 | 13→theory.11 It negates the basic assumptions of classical geopolitics and realism (therefore it is sometimes referred to as anti-geopolitics12) and criticizes, among other things, the treatment of the largest states as major geopolitical actors. It is because it recognizes the growing importance of social and economic interest groups operating across national borders, i.e., most often on a global or supranational scale. It also undermines the leading role of “objective” external conditions (structural or geographical). Rather, it emphasizes the role of cultural and ideological factors, as well as political discourse and the interplay of various interests in constructing geopolitical interpretations.

In the present volume, I use the term geopolitics as a combination of realistic and liberal approaches. (1) Geopolitics, understood in a classical way, as a rivalry of great powers (regional and world ones) for dominance, is of fundamental importance for my arguments. (2) I refer geopolitical interests first of all to the Raison d’État of each particular political community. In the case of the European Union, such communities exist at Member State level. A similar type of community has not yet developed at European level. There is, therefore, no European sovereignty or Raison d’État. This entails fundamental consequences for the understanding of geopolitical interests on the Old Continent since it explains the superiority of national interests and the deficit of geopolitical thinking on a pan-European scale. Moreover, I distinguish between the geopolitical Raison d’État of the entire community and the policy “appropriated” by particular interests. Even if French and German politicians mention European sovereignty,13 it can be assumed that they refer to a vision of the development of the EU (and its external policies) in line with the interests of France or Germany. (3) However, in accordance with the liberal approach, I refer the term geopolitics more to the “grand strategy” and leading political idea than to geographical conditions. In ←13 | 14→this context, I also interpret economic factors. For me, it is essential if there exists a public authorities’ strategy to stimulate economic development. It is equally important whether such a strategy aims to strengthen the geopolitical potential of a given country on the international arena and whether it is used for geopolitical purposes as a geoeconomic strategy.

What is geoeconomics?

The above considerations on geopolitics constitute a necessary introduction to clarify the very term. This is because, in my opinion, geoeconomics is a combination of geopolitics and economic policy, but also a combination of political science (mainly in the fields of international relations and European studies) and economics. Thus, we can distinguish two basic aspects of geoeconomics. On the one hand, it is a scientific discipline, and on the other, it is a political and economic practice.14 Geoeconomics links geopolitical strategy and economic policy in a complementary manner.15 While the two categories (i.e., social science and political activity) may be separate, in practice they often complement and stimulate each other. Most often, geoeconomics is defined as the use of economic instruments for geopolitical purposes.16 Such an approach assumes not only the interdependence of both areas (or these two scientific disciplines), but also the primacy of geopolitical objectives and interests over economic ones and the subordination of economic policy to geopolitical strategy.17

←14 | 15→The economy ceases to be treated only as a source of geopolitical potentials, i.e., resources increasing power in international relations or enabling military activity. Such is the strategic place of the economy according to the realistic school.18 In terms of geoeconomics, the economy is becoming an additional important instrument for gaining advantages in international relations, as well as an area of rivalry between the largest countries. According to Edward Luttwak, the creator of contemporary geoeconomics, with the end of the Cold War the rivalry among the superpowers shifted away from the sphere of military confrontation towards – in the first place – the field of the economy.19 In his conception, what remains of utmost importance is the rivalry for power, i.e., for which countries will assume the role of leaders and which will continue as subordinate. It is therefore an approach that is close to realism, as it presupposes confrontational and hierarchical shaping of international relations. Power is not distributed equally, and its essence is the asymmetry of mutual relations between states. For Luttwak, what constitutes the field of power rivalry is primarily the economy, and the economic instruments used by the states are aimed at gaining an advantage over their rivals. Other scholars have a similar approach.20 According to Samuel Huntington, at the end of the 20th century, economic power increasingly decided about the primacy (or political dominance) and subordination (dependence) of states, thus influencing the hierarchical geopolitical structure.21 ←15 | 16→According to other scholars,22 rivalry among great powers during this period increasingly focused on the control of economic resources, and less on territorial control (which is one of the main objectives of geopolitics). Geopolitical goals were still pursued through coercive measures (i.e., thanks to power exerted in international relations), but to a lesser extent by means of military instruments and more often through economic or regulatory pressure.23

Although the confrontation between the major powers has shifted towards the economy, this does not mean that there are no military conflicts between the powers. These are referred to as proxy wars24 and usually concern peripheral areas (although of strategic importance) rather than direct confrontation between the main rivals on a global scale.25 Thus, economic rivalry constitutes the transfer of conflict from the final (military) stage to the earlier one, i.e., related to the accumulation of potentials (different types of capital). It is a stage where one can gain asymmetrical advantage or even domination over rivals without the need to resort to costly and destructive military confrontation. That is why such actions are most often taken by emerging great powers, which seek to avoid premature rivalry (especially military) with the existing world powers.26

The geoeconomics of China is an example, which aimed at gaining geopolitical advantage over the western great powers, in particular the United States of America – to a large extent basing on the strategy of a “peaceful economic development.” Therefore, according to Luttwak,27 “strategic logics” will inevitably force deterring the growth of the Chinese power in the region and all over the world, by other great powers – first of all in the economic area.

←16 | 17→Geoeconomics is also considered as soft geopolitics.28 In the presented stance emphasis should be placed on achieving the political dominance, not only by means of accumulation of wealth, but by means of establishing lasting mechanisms of economic exchange, including regional or global economic regime which will be favorable to the leading power. Another element of the discussed approach is defining the authority/power in international relationships as – among others – an autonomy of a specific political entity. This mainly relates to external relations, hence the independence from the political or economic pressure. This also concerns internal autonomy, understood as an immunity of the public authorities to the abuse from the particular interests. This includes controllability of those authorities over the economy and the ability to use economic instruments for the foreign policy purposes. It can also be added that the internal autonomy stands for the capability to identify and pursue the geoeconomic objectives of the entire political community (also called – national interest or Raison d’État), rather than promoting only the most influential economic interests.

In accordance with the liberal tradition in the political sciences – the geoeconomic analysis should focus on the internal policy29. The goal of the geoeconomics under this approach is the accumulation of capitals (financial, technological, human and social), which is to lead to developing a highly competitive and pro-export economy, and thus to strengthen the geopolitical position of the state concerned. Regional policy may be an important geoeconomic instrument, which aims at strengthening the economic structures of own territory, as well as the social and educational policies whose goals are the development of a high quality of human and social capital.30 Therefore, the discussed approach towards geoeconomics can be determined as social one (and relates to the social geopolitics). It also provides a completely different geographical context for the geopolitical analysis. It is centered around the regional policy that is supposed to ←17 | 18→strengthen the economy in both most dynamic, and the slowly developing areas of the country.

Literature refers to a notion of “economic patriotism,” close to geoeconomics. It is defined as a political idea that supports specific groups of economic interests due to their territorial affiliation (e.g. to a specific state or political community)31. This brings about consequences in the external economic policy which mainly aims at economic benefits. However, it is the geopolitical goals that are of essential importance in the geoeconomic approach – even if economic actions are leading in them. Researchers using the term of economic patriotism indicate the widely varying mechanisms of its execution in practice. In addition to the traditional mercantilist or protectionist instruments, the methods of economic liberalism are applied more and more frequently, or a mixed approach is visible.32

It should be noted that it was before the end of Cold War that the scholars indicated the approach in foreign policy that was similar to geoeconomics, however they did not call it that. Most often it was a foreign (or international) economic policy, which – in addition to economic goals – could also have some political objectives33. The concept of economic statecraft in foreign policy was related to that.34 Others called it by the name of an economic leverage, i.e., use of economic resources in foreign policy.35 Still others used the term of economic warfare, i.e., using resources aiming at dominating the opponent or acting to their disadvantage.36 Undoubtedly, geoeconomics makes use of the earlier academic achievements, at the same time making it systematic and applying to the post-Cold-War reality.

In Polish literature, one of the pioneering works using geoeconomic terminology is a book edited by Edward Haliżak.37 It treats wealth and security as ←18 | 19→two equal needs of the state. According to the editor of this volume, geoeconomics is the “antithesis of geopolitics.” While the goal of geopolitics is security and its instrument is military strength, the goal of geoeconomics is to build a geoeconomic space that provides wealth.38 Richard Rosecrance presents a similar approach in this matter.39 According to him, countries have two parallel areas of strategic interest: geopolitical security and economic development. In the era of liberal order and growing interdependence – countries are increasingly preferring the economic pole over the geopolitical one. In this context, it is worth presenting the definition of geoeconomics that I have adopted.

Geoeconomics combines geopolitics, or “grand strategy” in international relations – with the economic policy embraced both in external relations, and the internal one. Geoeconomics subordinates economic policy to the geopolitical goals. It uses economic instruments to increase the power in international relations. Wealth (or accumulation of various types of capitals) is in my opinion a goal that is not equivalent to the safety, but it is to provide safety. Hence, geoeconomics is not an “antithesis of geopolitics,” but a geopolitical strategy that treats economy as the main geopolitical store, as well as an action instrument and the area of international rivalry.40

Geoeconomic instruments and endowments

Therefore, economic development serves to increase the power of the state, both enabling the influence on other actors and to maintain political or economic autonomy. Thus, economic growth strengthens the structural position of the given entity on a regional and global scale. For Robert Blackwell and Jennifer Harris, building long-term advantages or endowments in international relations is of fundamental importance in geoeconomic strategy. They should be formed in several areas.41 First of all, the size of the internal market, its level of growth, ←19 | 20→as well as skillful control of access to this market are important both for the import of services and goods, as well as external investment capital (especially in the field of industry and technology). Opening up access to external outlets for domestic exports is another important element. It is best when state authorities can ensure an advantage of exports over imports, because this leads to the accumulation of financial reserves. Another factor is securing raw materials, especially energy, for the development of the national economy. Finally, the potential of the financial system and the international currency, which can be a source of advantages in trade exchange and capital flows, are of great importance.

In turn, for Samuel Huntington, it is crucial to build the strength of the domestic industry, which should prioritize the interests of this sector of the economy over consumer interests. An important aspect of these activities is the government’s industrial policy focused on selected sectors that are important for the strategic development and competitiveness of the economy. Another factor is the expansion of markets for production, including through technological advantage or dominance (monopolistic position) in specific sectors. At the same time, geoeconomics assume protecting its own market and limiting imports. Finally, the accumulation of financial capital is important, especially reserves that can be directed towards investments.42

In relation to these academic papers I wanted to present my own catalogue of areas or activities that can build geoeconomic advantages. In part, they complement and in part repeat the previously mentioned factors. As I said before, capital accumulation is crucial. It is about the development of resources in finances, technology, raw materials, employment sectors (primarily population size and education) and social fields (understood as the level of integration, motivation, identification and trust towards own political community and public authorities). From the point of view of geoeconomics, the combination of innovation and industrial policy as well as scientific and educational policy are of major importance. They build the foundations for long-term growth, international competitiveness of the specific economy, technological advantages, and thus the possibility of capital accumulation resulting from export activities. Currency exchange rate policy is also important, as it can stimulate an exchange rate that is favorable for exports. In addition, capital flow control and control over the financial system (banks) is of great importance. They ensure economic stability and credit for industrial and service investments43. Like Blackwill and Harris, ←20 | 21→I think that the international role of the currency is important, as is the security of supply of raw materials, especially those related to energy. Another factor supporting economic exchange and energy security is the suitable development of transmission and communication infrastructure.44

An important aspect of geoeconomics is striving to build lasting economic exchange relations that will be maximally beneficial for a given country, and at the same time less convenient or even leading to economic dependence for its rivals. This includes constructing economic regimes on an international scale, as well as using them to obtain lasting competitive advantages or asymmetrical benefits over major competitors. These economic systems can be a source of wealth, including through the exploitation of dependent areas. They can also form the basis for political power in international relations. Here, control over international regulations or even transferring national solutions to a regional or global level is of crucial importance.

The scholars indicate45 various geoeconomic instruments, such as economic sanctions, embargos (including on access to resources), boycott of imports or punitive duties imposed on imports, capital control, within this scope supervision of domestic companies acquisition by foreign capital, suspending developmental (or anti-crisis) aid, etc. Positive instruments are also mentioned, for example subsidies, financial guarantees or other forms of support for export, providing preferential access to the internal market (among others, the status of the most-favored nation). It is worth noting that the source literature had included work before, which proved that the economic instruments are often used for geopolitical purposes.46 The examples of international sanctions, development and anti-crisis aid, including those with political conditions attached, were most often cited.47 In recent years, this catalog has been expanded, proving ←21 | 22→that the geoeconomic instruments also include controlling the ownership of the means of production and the chain of production processes. Investment restrictions for foreign entities are another such instrument, especially in industries that are considered strategic. Foreign investments may be aimed at taking over and dominating the local sales market, as well as acquiring unique technologies. Another geoeconomic instrument may be the regulatory obligation of technology transfer by foreign investors to local companies or the theft of technology organized by special services. As you can see from all these examples, one of the most valuable resources of strategic importance is possessing technologies that are not only a source of competitive advantages on global markets, but also often have military applications, thus directly affect geopolitical competition.48 Therefore, in the early 21st century, IT technologies, including work on artificial intelligence, have been some of the most important areas of geoeconomic competition.

Theoretical interpretations of geoeconomics

As part of political economy, there are three main schools analyzing the role of the state in the economy, included within the scope of international economic relations. These are (1) liberalism, (2) Marxism and close to (3) realism – statism, mercantilism and concepts of the developmental state. The geoeconomic perspective is most strongly present in the latter mentioned theoretical trend, although it can also be found in other paradigms.

An example is the work of representatives of classical liberalism. The Adam Smith’s political economy sought to explain the causes of the wealth of nations, and especially to develop the best policy for the Great Britain of that time. The goal of public authorities was to be the wealth, which is close to the geoeconomic accumulation of capital. Both Smith and David Ricardo recognized capital accumulation as a fundamental factor of development (in addition, Ricardo emphasized the importance of technological innovation49). In addition, it was important ←22 | 23→to strive for the value of exports to be higher than imports50. This is also in line with geoeconomic assumptions.

Both of them criticized mercantilism, assumed that the state would refrain from economic interventionism, and promoted the idea of self-regulation of markets. For example, Ricardo recognized that state intervention leads to inefficient allocation of capital, and thus reduces overall welfare.51 The classic approach recognizes that the state only creates a general framework for economic activity, including ensuring contract enforceability and peaceful conditions for international trade. This deviates from geoeconomic assumptions, under which state policy can also increase the competitiveness of the local economy, including through industrial and innovation policy, and actively supports the development of export.

However, some passages in the works of classic economy theorists quite well refer to the geoeconomic approach. For example, Smith was a pragmatist, above all. Liberal principles had to give way in the face of strictly geoeconomic principles. According to Smith, state interventionism was necessary in a situation of a threat to national (and thus geopolitical) security. In addition, protectionism for domestic production was possible, for example, when imported goods had lower taxation in the country of origin or when retaliation was required for earlier restrictions imposed on the export of goods from England. Finally, the liberalization of trade, according to Smith, should be introduced gradually, so that the domestic industry had the opportunity to improve competitiveness and face up to foreign rivals. He described the excessive attachment to the total liberalization of British trade as “utopian.”52

The subsequent liberal concepts were increasingly moving away from thinking in geoeconomic terms. An example is the theory of interdependence, which has a big impact on shaping the liberal paradigm in political economy. The precursor ←23 | 24→of this direction was Norman Angell.53 A few years before the outbreak of World War I, he argued that the growing economic interdependence between states made war in Europe irrational – as well as the geopolitical competition for territory. Continuers of this approach in the second half of the twentieth century assumed54 that growing globalization not only brings economic and political interdependence, but gradually limits states. The importance of military rivalry, and therefore also geopolitics, is diminishing. The role of economic networks and non-state actors, e.g. large corporations, is growing. Interdependence of economic relations is more a source of shared benefits than unequal distribution of benefits and costs. Although there is an asymmetry of potentials and wealth between individual actors, it is not a source of the growing hierarchical power of one state over another. Rather, it leads to a limitation of state power. It is able to control domestic resources to some extent and as it may initiate international activities, it still has no effect on their results. Liberals rarely use the term geoeconomics, but if so, then they assume that it serves the administrative apparatus to support achieving economic goals.55 All this means that in a liberal world of interdependence and mutual benefits, as well as the limited possibilities of states in economic policy, it is more difficult to find justification for geoeconomic purposes. This does not mean, however, that this way of thinking is deprived of aspects of this type. In fact, economic development, increasing international economic exchange and interdependence ensure international stability, and thus promote peace.

However, with the passage of time in the liberal approach to political economy, the advantage of economic rationality over geopolitics gradually increased, which hindered the possibility of applying geoeconomic interpretations. To the greatest extent, it concerned the theoretical thought arising from the inspiration of neoliberalism in economics. Under its influence, further restrictions were imposed on state interventionism, including in external economic policy. Rather, recommendations were for a consistent liberalization of regulations or for leaving regulations to market entities (on the basis of the ←24 | 25→so-called self-regulation)56. This led to the rejection or at least the limitation of thinking in geoeconomic terms in those countries that were guided by the neoliberal paradigm.57 At the same time, it is an interesting example of the impact of economic ideas on shaping state policy.

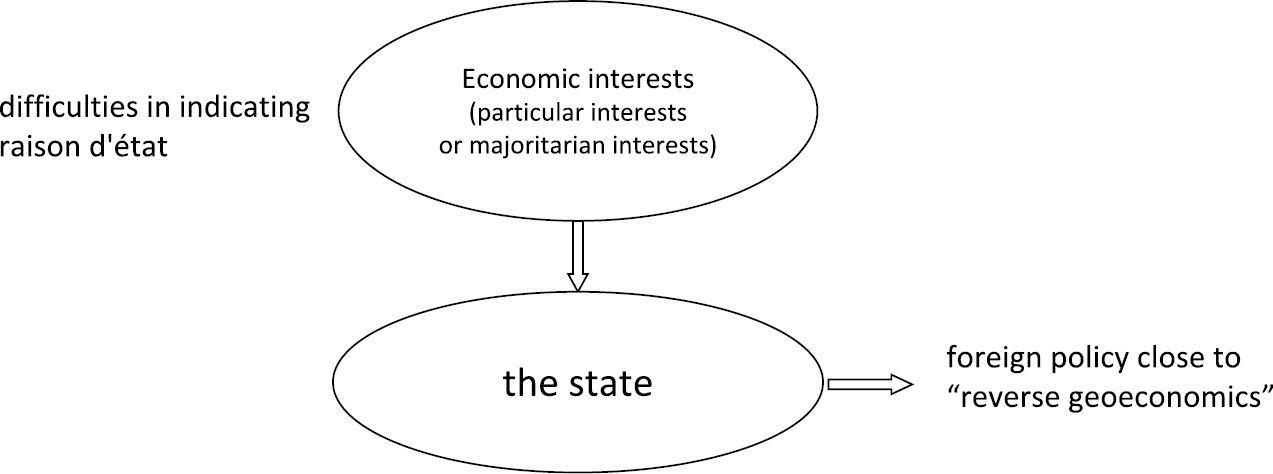

A characteristic feature of the liberal approach – this time derived from political sciences – is the emphasis on the role of grassroots economic interests in formulating goals in external economic policy.58 According to this approach, these interest groups often have an overwhelming influence on foreign policy directions, smuggling into it their own understanding of distribution benefits.59 For example, according to the Stolper-Samuelson theorem, scholars predict60 that the large capital supports the liberalization of economic exchange with foreign countries, while groups representing employees’ interests are against it. In this way, the liberal approach considers it natural that external economic policy is shaped primarily by the most influential national economic interests, and not, for example, by external and objective geopolitical considerations. This has major implications for geoeconomic analysis. In liberal thinking, there is no supreme national interest with a geopolitical dimension that would direct economic policy instruments or create conditions for supporting national economic interests in external relations. Instead, the logical consequence of using liberal thinking may be the phenomenon of “appropriation” of foreign policy or its “capture” by the strongest economic interests. This can also be referred to as “reverse geoeconomics.” It is not the geopolitical interests that subordinate the economic policy tools and direct the actions of entrepreneurs or investors, but the opposite – it is the most influential economic interests that use the state apparatus in foreign policy. Critics of liberalism indicate that, according to this paradigm, the ←25 | 26→state and its foreign policy only have a utilitarian role in relation to economic interests, i.e., most often the largest corporations or financial institutions.61 They also point to the lack of autonomy of the state towards particular interests.62

Figure 1 Model of external economic policy from the liberal perspective

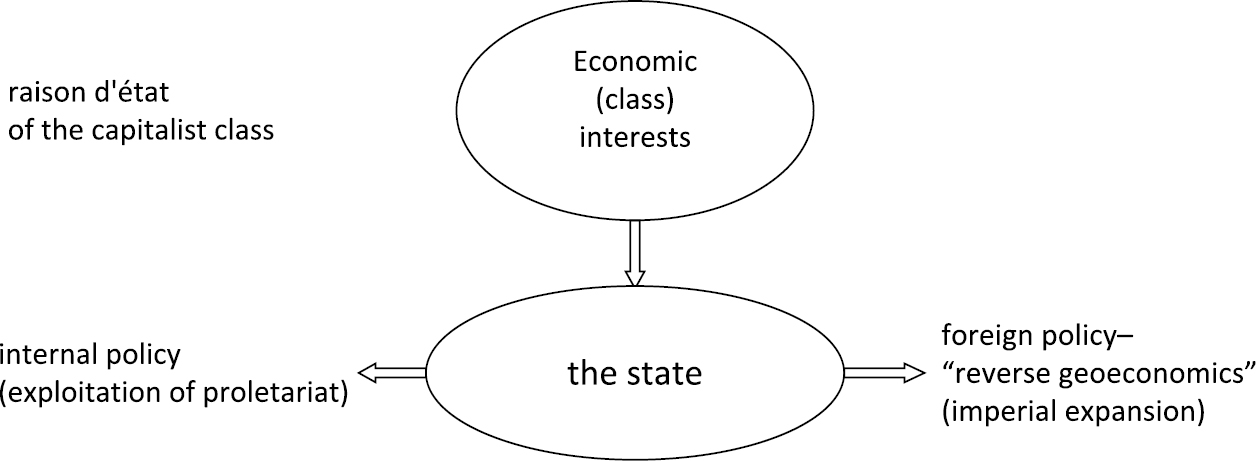

Marxism is another paradigm in political economy that is relevant to the geoeconomics deliberations. The central assumption of the discussed theory is that capitalist states perform a service role for capital accumulation.63 Under the class social system, capitalists gain the highest position and power in the state. They use state structures on the one hand for internal exploitation of subordinate classes (proletariat), and on the other hand, for external expansion, which is to increase their profitability.64 Thus, foreign policy provides economic benefits to the ruling class, including through the exploitation of colonies, preferential conditions for foreign trade or the introduction of mechanisms of dependent development in areas with weaker geopolitical position. Marxist concepts do not deny existence of geopolitics, but subordinate it to the interests of the capitalist class. The extension of these views is the “imperial geopolitics” of Vladimir I. Lenin.65 In this approach, the highest stage of the capitalist economy is the transition from productive activity to financial activity, which focuses power in the hands of the ←26 | 27→financial oligarchy. The possibilities of capital accumulation on a large scale are created only by external expansion, which means that capitalist great powers are heading to hegemony on a regional or global scale. It is noteworthy that Lenin took some thoughts from John Hobson.66 For example, the view that the imperialism of European great powers resulted from the earlier accumulation of capital and the search for ways to find better opportunities to invest surplus savings (i.e., higher rates of return due to colonial expansion). This is somewhat reminiscent of the spread of financial investments from wealthy Western countries as part of the modern stage of economic globalization.

In Marxist terms, it is the economic interests that are superior to the geopolitical ones – they even set directions for foreign policy. This is reminiscent of a “reverse geoeconomics” situation in which the greatest economic interests make use of the instruments of state authority and foreign policy to achieve their own goals. They are not, however, the particular interests or those arising as a result of aggregation of partial interests or discourse between them (which creates interests that can be described as those of majority), as is the case in the liberal approach. Marxists recognize the specific national interest which is the collective interest of the entire capitalist class and is not the sum of individual economic interests.67 As I have mentioned, the main class goal is the accumulation of capital (wealth). Nevertheless, capitalists in the Marxist approach do not lose geopolitical instincts and, above all, responsibility for their own state, which is the main vehicle for the realization of their interests. The “power of the state” – including the military one and this in the international perspective – is therefore an important assumption of the Marxist geoeconomics model. For example, for the representatives of critical Marxist geopolitics,68 the US military operations in the Middle East conducted since the 1980’s have served geoeconomic purposes, i.e., securing free trade in energy resources in the Persian Gulf. The wars waged in Iraq and in Afghanistan were supposed to lead to the later economic reconstruction of both countries and their integration into the global economic exchange.

Some theorists of critical geopolitics69 point to the changing geoeconomics of the largest powers. While in the 19th century the capitalist class encouraged European great powers to carry out colonial conquests, in the 20th century the ←27 | 28→USA largely departed from the logic of territorial conquest as a means of capitalist expansion. For the United States, dominance over the global economy was sufficient, including control of major institutions, regulatory influence, international dominance of the US dollar, and the advantage of American corporations on world markets. This approach follows the typology of David Harvey.70 He distinguishes the territorial logic that states use for geopolitical purposes and the capitalist logic aimed at the accumulation of capital on a global scale, which will not be limited either by national borders or state territory. Both logics are interrelated and interdependent for Harvey, but for a critical geopolitical approach, territorial logic began to lose its significance in the age of globalization. The aforementioned scientific approach is close to constructivists, because geoeconomic narrative is crucial in this research.71 It served in the largest extent the expansion of capitalists, including the elimination of limitations on this expansion resulting from the existing borders and state protectionism. The narrative could also serve regional and global integration, which was beneficial for great capital and limited the power of states, especially the smaller ones. Over time, some critical geopolitics scholars began to see the interdependence of capitalist and territorial logic, which they referred to as “geoeconomic dialectics.”72 The first logic, according to Marxist tradition, meant using the instruments of the state (or regional organization) to promote the interests of the big capital. However, it was associated with the simultaneous process of instrumentalizing the economy for geopolitical purposes, primarily by the largest countries. In the latter case, the narrative referring to economic goals could justify or even legitimize in the international forum the geopolitical intervention including the military one.73 In this way, the concept of “geoeconomic dialectics” was an important complement to Marxist thought. That is because it noticed the bilateral possibility of using both the state ←28 | 29→by capitalists and the economic instruments by the state apparatus, for geopolitical purposes.

Figure 2 Geoeconomics model as viewed by Marxism

Mercantilism or a related statist approach, as well as other concepts originating from the realistic school, are another type of political economy that is important for geoeconomic analysis. In the discussed paradigm, the state plays a key role both in achieving goals in international politics and in supporting economic development. Both goals complement each other, although realism gives the dominant importance to geopolitical interests. This means that the economy is an important potential and instrument for implementing a geopolitical strategy, and economic entities can thrive within the political framework established and guaranteed by a given geopolitical order.

Friedrich List was the precursor of the mercantilist approach in political economy. The distinction between social (of a specific political community) and individual interests is fundamental to his views.74 At the same time, he recognizes the primacy of the common interest over the particular ones, and the need for the state to pursue this interest. This includes, in particular, the need to support the local economy, however not individual enterprises, but rather entire industries or sectors. For example, the state has a duty to protect weaker economies against competition from the stronger ones. According to List, the promotion of liberal principles by English economists at the turn of the 18th and 19th centuries was associated with the fact that the contemporary UK economy was stronger than most other European economies, and thus benefited from liberal trade.

←29 | 30→List finds it of a fundamental significance to focus the public authorities’ policy on the interest of the entire political community, which is close to my understanding of the national interest. In addition, he recognizes that the economic development policy, including the promotion of exports and possibly the protection of domestic industry against stronger foreign competition, is an important community goal. It is an approach close to geoeconomics, in which the national economy is an important geopolitical resource.

A realist approach to political economy emphasizes the superiority of geopolitics (represented by the state apparatus) over economic interests (e.g. the goals of the largest companies). The work of Robert Gilpin is an example of this position.75 He sees the possibility of “emancipation” of large corporations above their own nation-state, and thus functioning on a global scale and without a sense of responsibility for the domestic economy and society. However, he doubts that these economic elites could “appropriate” the political structures of their countries for their own purposes. However, he emphasizes that economic interests can be developed in international relations only thanks to the geopolitical strength of their native countries and within the regulatory framework established by the major powers. The stronger the state in the geopolitical system, the bigger its impact on organizing the economic order. He also recognizes that corporations often contribute to the promotion of geopolitical interests or otherwise strengthen the power of their own countries in external relations. At the same time, countries tend to maximize economic benefits as part of international exchange. An example of such behavior is the economic regime created by the USA after World War II. According to Gilpin, although it was developed around liberal ideas, it still favored and protected American economic interests, and thus contributed to the political domination of this superpower in the world.

Several basic geoeconomic assumptions can be found in this approach. First of all, the superiority of geopolitics over economics, as well as the use of economic policy instruments for geopolitical purposes. There is also a feedback mechanism between both realms.76 It consists in the fact that the geopolitical power of the largest countries originates, among others, from the resources of the national economy and uses its instruments. At the same time, the interests ←30 | 31→of business entities are implemented thanks to the support of states, including in the international arena.

Three categories of authority introduced by scholars using the realist paradigm in political economy are also important for geoeconomic analysis. It is primarily about the distinction between “structural power” and “relational power” in international relations.77 In the first case, the authority of a given state causes automatic structural adjustments of other entities, in line with its interests, but without the need for any direct political intervention. In contrast, “relational authority” means exerting pressure on external entities, as a result of which they adapt their policies to the expectations of the dominant state. Another important category concerns the maintenance of power over its own territory, including the national economy. It is an indispensable element of effective geoeconomics which combines controllability in internal policy with exerting influence in external relations. In the internal context, we can mention the concept of autonomy of public authorities discussed earlier (autonomy from excessive influence on the part of particular interests) and recall the term of “state capacity,” understood inter alia as the ability of state administration to effectively and efficiently implement economic policies.78

Details

- Pages

- 506

- Year

- 2020

- ISBN (PDF)

- 9783631824627

- ISBN (ePUB)

- 9783631824634

- ISBN (MOBI)

- 9783631824641

- ISBN (Hardcover)

- 9783631812167

- DOI

- 10.3726/b17064

- Language

- English

- Publication date

- 2020 (June)

- Keywords

- geoeconomics energy sector internationalization of currency military technologies geopolitics

- Published

- Berlin, Bern, Bruxelles, New York, Oxford, Warszawa, Wien, 2020. 506 pp., 19 fig. b/w, 3 tables.