1. Introduction

Urban public services (UPS) can be defined as those activities that meet citizen needs through a physical system of the production, distribution, provision, and consumption of basic goods [

1,

2,

3]. Many studies have influenced both the technical and economic importance afforded to UPS, which are fundamental for the operation of cities [

4,

5,

6,

7] and which include the provision of resources and the collection and disposal of waste [

8,

9], the distribution of energy and public lighting [

10,

11], and the maintenance of communication and transport infrastructure [

12,

13]. Among them, water management is a key element, being provided by means of various UPS: on the one hand, the supply and distribution of drinking water [

14,

15,

16] and, on the other, the sewage collection system [

17]. Moreover, a municipality’s urban policy is typically dependent on a combination of public, private, and mixed UPS management. Indeed, while the ownership of the services remains public, there are many instances around the world where municipalities prefer to outsource these services and privatize their management to achieve greater efficiency [

18,

19].

The proper planning of UPS provides citizens with a better quality of living. Here, the relationship between the core and the periphery can take on particular importance. Thus, suburbs usually experience complex problems related to a UPS deficit [

20,

21,

22], and rural areas with low population density likewise present problems of accessibility for UPS [

23,

24,

25,

26], typified by few transportation and mobility resources [

27,

28]; an intermittent water supply system [

29,

30]; and scarce or remote health facilities [

31,

32,

33], schools [

34,

35], and police and fire stations [

36,

37]. Indeed, various studies propose an enhanced distribution of UPS in rural areas based on a location-allocation approach using Geographic Information System (GIS) techniques [

38,

39,

40,

41].

Policies to decentralize and improve accessibility to UPS are one of the challenges faced by governance at different territorial levels, including border areas [

42,

43,

44,

45,

46,

47]. Such policies, as noted above, are necessary in remote and rural areas. Furthermore, if these areas are located along national or regional peripheral borders (i.e., external or internal borders, respectively), the outlook may be even worse in the absence of both cordial relations and inter-administrative cooperation. Indeed, the “barrier effect” can result in a testing situation for the administrations involved [

48,

49,

50], making cooperation between cross-border areas essential in such sectors as tourism [

51,

52,

53,

54], healthcare [

55,

56], and natural resource management [

57,

58,

59], among others. The policy of supra-state entities—most notably, the European Union (EU)—has, in recent decades, worked in this direction—that is, the strengthening of cooperation between states and a curtailing of the adverse effects of the classic border [

60,

61,

62,

63,

64,

65].

Inter-administrative cooperation is more readily addressed in internal border areas that form part of the same state and which share common policies, such as UPS management. However, cooperation is closely linked to the state’s internal policy of organization; for example, in most decentralized states the barrier effect of the state’s internal borders tends to be more acute, as is the case in Spain [

66,

67]. The need for the cooperative, shared management of UPS becomes essential for proper spatial planning in territories located some distance from the metropolitan region and suffering marked socioeconomic deficiencies.

The aim of this paper is to describe the role and determine the performance of UPS management in a peripheral rural border area, and to explore and analyze the perceptions that stakeholders have of inter-administrative cooperation between the border regions in the same decentralized state. The border area we study here is differentiated at an administrative level between the Spanish regions or Autonomous Communities of Aragon and Catalonia, yet the territory shares a common physical environment (the basin of the river Ebro) and presents considerable potential for implementing common objectives centered on the management of their UPS. A further aim of our study is that its results might be taken into account by the corresponding administrations and practitioners so as to create the appropriate instruments to solve existing deficiencies and to achieve greater efficiency in the management of UPS.

In seeking to fulfil these aims, this paper (1) reports a quantitative study conducted in the internal border area between two Spanish regions (Aragon and Catalonia); (2) identifies and analyzes inter-administrative cooperation in the delivery of UPS using quantitative methods; and (3) proposes future research on the issues addressed.

2. Materials and Methods

The present study is framed in the context of a broader research project, focused on the analysis of different types of problem and conflict that have been generated in recent times (especially over the last four decades) in the internal border area (IBA) between three Spanish Autonomous Communities: Aragon, Catalonia, and the Valencian Community. The results of this research have been reported in a number of studies conducted at different scales and focusing on different themes [

68,

69,

70]. These previous studies, based on the conducting of focus groups with public stakeholders (mayors and town clerks) in the territory analyzed, conclude that, for a significant majority of the problems considered, it is essential that cooperation be promoted between the autonomous administrations. The present article seeks to build on the findings of these earlier studies by employing a questionnaire as a valid and rigorous methodology for collecting information about stakeholder perceptions [

71,

72,

73,

74,

75].

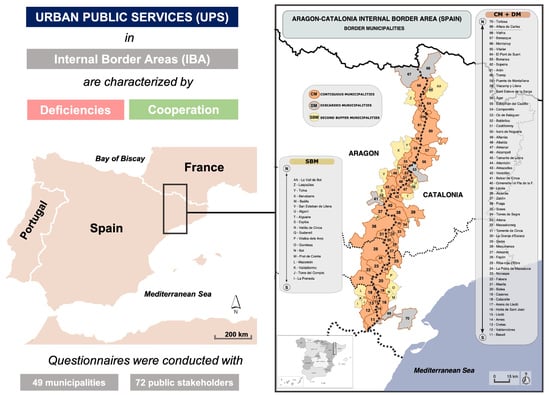

While some of our previous studies have focused on the Catalonia–Valencian Community IBA, the present study focuses solely on the Aragon–Catalonia IBA (ARCAT-IBA,

Figure 1). This area, with a border extending some 360 km, forms part of the Ebro basin and is characterized by its tributaries that run from north to south (Noguera Ribagorçana, Cinca, Matarranya) and a sub-tributary (Algars), which serve as the boundary. Specifically, a total of 57 border municipalities make up the ARCAT-IBA (CM in

Figure 1), with an additional 19 (SBM in

Figure 1) which, due to their size and proximity, play a secondary role in the border dynamics.

A questionnaire for the ARCAT-IBA public stakeholders (mayors and town clerks) was created with five main objectives: (i) to determine their perception of the deficiencies in UPS management as a result of the different regulations being operated in Aragon and Catalonia, respectively (Q1 in

Table 1); (ii) to identify the existence of any formal or informal mechanisms of cooperation being employed by the Catalan and Aragonese administrations (Q2 and Q3 in

Table 1); (iii) to appreciate their willingness to strengthen inter-municipal cooperation in the management of UPS, so that the citizens of ARCAT-IBA municipalities might access these services regardless of their origin (Q4 and Q5 in

Table 1); (iv) to identify instruments to correct the deficiencies detected (Q6 in

Table 1); and, finally, (v) to determine their perception of deficiencies at higher administrative levels (Q7 in

Table 1). The questionnaire was answered in person between January and June 2017, following focus group sessions analyzed in previous studies devoted to water management [

70]. Although there is evidence of general problems affecting local government in Spain and UPS management (e.g., budget deficits and shortages of administrative personnel), the questionnaire focuses on the specific problems attributable to their condition as border municipalities. Note that Q5 refers to the UPS specifically listed in Spanish regulations [

76].

The study carried out presents a series of specific methodological characteristics: (i) to facilitate comparison with our previous studies, the numbering given to the contiguous border municipalities (CM) is respected (11–70 in

Figure 1); (ii) the second buffer municipalities (SBM) (AA-I in

Figure 1) are those located adjacent to the CM and play a secondary role in the border dynamics, so are not included in this study; (iii) as in previous studies, some border municipalities (DM in

Figure 1) have been discarded due to their secondary role in the border dynamics resulting from physical geographical barriers or the extent of their border area; (iv) 8 of the 57 Catalan and Aragonese municipalities did not participate (

Table 2); (v) 72 stakeholders participated in our study by answering the questionnaire (38 mayors and 34 town clerks), representing 57.1% of the potential stakeholders (

Table 1); (vi) in most municipalities, both stakeholders participated (mayor and town clerk), but in some only one of the two participated: mayors only (11, 12, 36, 42, 45, 54, 57, 60, and 64 in

Figure 1) and town clerks only (15, 25, 32, 35, 38, 39, 52, and 53 in

Figure 1).

4. Discussion and Conclusions

UPS management is essential for the well-being of the population, whose basic needs must be met through the provision of these services by different administrative levels (local and supralocal). Rural areas, located far from metropolitan urban centers, are more likely to suffer a lack of proper UPS management. Moreover, when rural areas are also peripheral border areas, this situation is likely to be exacerbated. Here, with the aim of analyzing the management of UPS in rural-border areas, we have carried out a quantitative study of the perception of public stakeholders (mayors and town clerks) in the case of the Spanish internal border area between Catalonia and Aragon (ARCAT-IBA), characterized by the river municipalities of the Ebro basin.

The perception of the existence of deficiencies in UPS management is shared on both sides of the border. Moreover, there is also a common perception that there are not enough cooperation mechanisms to correct these deficiencies. In fact, on both sides of the border, a significant percentage of stakeholders agree that the creation and implementation of cooperation mechanisms for UPS management would be a positive step forward.

The differences in perception regarding the degree of cooperation (existing or desirable) between the municipalities on both sides of the border cannot be considered significant in themselves. There are a number of factors of a geographical nature, linked to the heterogeneity of the whole border area (including the discontinuous distribution of urban settlements and the weak relationship between some municipalities), which condition this perception and which mean that, in many cases, the same situation or problem is interpreted differently on the two sides of the border. These divergences in perception (which can be considered inherent to the border territories, given their usual condition of “periphery” in relation to their respective “centres”) could be better understood by conducting a detailed study of just a few municipalities and, in this way, leaving to one side the problems faced by the whole border area.

There is also a shared perception of the positive effects of the collaborative management of UPS for achieving common objectives for people on both sides of the border. This is particularly the case for both local and supralocal UPS competences, such as the promotion of river tourism, town access roads, urban collective passenger transport, and environmental protection, which Catalan and Aragonese public stakeholders alike feel would benefit from greater cooperation. There is also a moderate level of agreement that other competences, such as civil defence, healthcare, police, the paving and maintenance of public roadways, and social services, would benefit from cooperation. All these competences are basic for the social and economic development of peripheral rural border areas.

The promotion of cooperation mechanisms via the creation of a new special entity in the Spanish legal system (the “border municipality”) could be way to achieve a satisfactory agreement between the two sides in the long term. This entity could usher in the establishment of different, specific, and more favorable regulations for the socioeconomic development of peripheral municipalities located on Spain’s internal borders. In contrast, other more frequently employed formal solutions (i.e., agreements, consortiums, and commonwealths) do not, in many instances, result in a significant degree of cooperation, as they are usually designed for specific scenarios or to address specific problems.

Furthermore, the common perception is that the supralocal administration has been indifferent and distant (neither contrary nor favorable) in its stance to the mechanisms of cooperation. We conclude that the ARCAT-IBA is a territory that is favorable to cooperation in different competences that directly affect UPS management, and that local and supralocal public administrations should take into account this perception of stakeholders to achieve beneficial outcomes for both sides of the border.

Further quantitative research on the questions studied here is needed. The geolocation of UPS and associated statistical analyses aimed at creating efficient location-allocation models should help promote the willingness to cooperate that has been detected using the quantitative methods employed in this study. In addition, the need should be stressed for good decentralization policies and for the consideration of IBAs as a whole territory subject to the same deficiencies in UPS management and, hence, sharing the same common objectives. Finally, more research on possible cooperation mechanisms, including at the international level, should shed further light on the subject.

We would like to complete this study by highlighting the need also to undertake further research on the management of public services. First of all, because we start from the principle that public services should be implemented equally throughout a territory (whatever its scale) and that it is not admissible, from the point of view of the provision of these services, that a distinction be made by the administration between “central” territories, on the one hand, and “peripheral” territories on the other. From an academic point of view, it is important to highlight that border areas (whether at the regional or state scale) often tend to become peripheral spaces (that is, spaces where deficits accumulate and where the limitations of administrative action are accentuated) and that, in such circumstances, it is essential that public authorities seek to correct these situations of imbalance in order to guarantee equity and territorial cohesion. Secondly, our research illustrates, we believe, the rich scientific possibilities opened up by conducting research in the field and more specifically by entering into dialogue with the stakeholders involved in the situations analyzed. In the course of this study, we have been able to observe that, above and beyond the problems identified and the material difficulties that often exist to address them when taking a “top-down” approach, cooperation mechanisms (which, as a rule, operate from the “bottom-up”) often offer practical and highly effective solutions that are worth careful consideration with a view to the future.