The Membrane-Anchoring Region of the AcMNPV P74 Protein Is Expendable or Interchangeable with Homologs from Other Species

Abstract

:1. Introduction

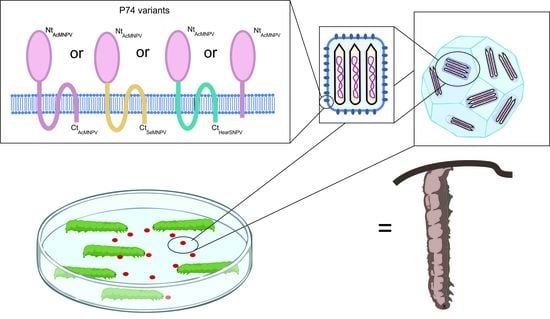

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. In Vitro Cell Culture and Insect Rearing

2.2. Bioinformatics Studies

2.3. P74 Gene Knockout in AcMNPV-bacmid

2.4. AcMNPV-bacmidΔp74 Complementation

2.5. OB Generation for the Recombinant Baculoviruses

2.6. Bioassays with Recombinant AcMNPVs

3. Results

3.1. P74 Phylogeny and Protein Domains

3.1.1. Phylogeny

3.1.2. Protein Domains

3.2. AcMNPV Knockout in p74 Gene and Complementation

3.2.1. CRISPR/Cas9 Application

3.2.2. AcMNPV OBs with P74 Variants

3.3. Infectivity of AcMNPV Variants

3.3.1. Infectivity of AcMNPV Variants in S. exigua

3.3.2. Infectivity of AcMNPV Variants in R. nu

4. Discussion

5. Conclusions

Supplementary Materials

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Szewczyk, B.; Rabalski, L.; Krol, E.; Sihler, W.; De Souza, M.L. Baculovirus Biopesticides—A Safe Alternative to Chemical Protection of Plants. J. Biopestic. 2009, 209, 209–216. [Google Scholar]

- Rohrmann, G.F. The AcMNPV Genome: Gene Content, Conservation, and Function. In Baculovirus Molecular Biology; National Center for Biotechnology Information: Bethesda, MD, USA, 2019; Volume 113. [Google Scholar]

- Williams, T.; Bergoin, M.; van Oers, M.M. Diversity of Large DNA Viruses of Invertebrates. J. Invertebr. Pathol. 2017, 147, 4–22. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Slack, J.; Arif, B.M. The Baculoviruses Occlusion-Derived Virus: Virion Structure and Function. Adv. Virus Res. 2006, 69, 99–165. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Herniou, E.A.; Jehle, J.A. Baculovirus Phylogeny and Evolution. Curr. Drug Targets 2007, 8, 1043–1050. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Jehle, J.A.; Blissard, G.W.; Bonning, B.C.; Cory, J.S.; Herniou, E.A.; Rohrmann, G.F.; Theilmann, D.A.; Thiem, S.M.; Vlak, J.M. On the Classification and Nomenclature of Baculoviruses: A Proposal for Revision Brief Review. Arch. Virol. 2006, 151, 1257–1266. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hu, Z.H.; Arif, B.M.; Jin, F.; Martens, J.W.M.; Chen, X.W.; Sun, J.S.; Zuidema, D.; Goldbach, R.W.; Vlak, J.M. Distinct Gene Arrangement in the Buzura Suppressaria Single-Nucleocapsid Nucleopolyhedrovirus Genome. J. Gen. Virol. 1998, 79, 2841–2851. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Lung, O.; Westenberg, M.; Vlak, J.M.; Zuidema, D.; Blissard, G.W. Pseudotyping Autographa Californica Multicapsid Nucleopolyhedrovirus (Ac M NPV): F Proteins from Group II NPVs Are Functionally Analogous to Ac M NPV GP64. J. Virol. 2002, 76, 5729–5736. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Green Version]

- Oomens, A.G.P.; Blissard, G.W. Requirement for GP64 to Drive Efficient Budding of Autographa Californica Multicapsid Nucleopolyhedrovirus. Virology 1999, 254, 297–314. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Jkel, W.F.J.; Lebbink, R.J.; Op Den Brouw, M.L.; Goldbach, R.W.; Vlak, J.M.; Zuidema, D. Identification of a Novel Occlusion Derived Virus-Specific Protein in Spodoptera Exigua Multicapsid Nucleopolyhedrovirus. Virology 2001, 284, 170–181. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Pearson, M.N.; Groten, C.; Rohrmann, G.F. Identification of the Lymantria Dispar Nucleopolyhedrovirus Envelope Fusion Protein Provides Evidence for a Phylogenetic Division of the Baculoviridae. J. Virol. 2000, 74, 6126–6131. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Pearson, M.N.; Rohrmann, G.F. Transfer, Incorporation, and Substitution of Envelope Fusion Proteins among Members of the Baculoviridae, Orthomyxoviridae, and Metaviridae (Insect Retrovirus) Families. J. Virol. 2002, 76, 5301–5304. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Blissard, G.W.; Theilmann, D.A. Baculovirus Entry and Egress from Insect Cells. Annu. Rev. Virol. 2018, 5, 113–139. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dong, Z.Q.; Zhang, J.; Chen, X.M.; He, Q.; Cao, M.Y.; Wang, L.; Li, H.Q.; Xiao, W.F.; Pan, C.X.; Lu, C.; et al. Bombyx Mori Nucleopolyhedrovirus ORF79 Is a per Os Infectivity Factor Associated with the PIF Complex. Virus Res. 2014, 184, 62–70. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gutiérrez, S.; Kikhno, I.; Ferber, M.L. Transcription and Promoter Analysis of Pif, an Essential but Low-Expressed Baculovirus Gene. J. Gen. Virol. 2004, 85, 331–341. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Haas-Stapleton, E.J.; Washburn, J.O.; Volkman, L.E. P74 Mediates Specific Binding of Autographa Californica M Nucleopolyhedrovirus Occlusion-Derived Virus to Primary Cellular Targets in the Midgut Epithelia of Heliothis virescens Larvae. J. Virol. 2004, 78, 6786–6791. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Green Version]

- Peng, K.; van Oers, M.M.; Hu, Z.; van Lent, J.W.M.; Vlak, J.M. Baculovirus Per Os Infectivity Factors Form a Complex on the Surface of Occlusion-Derived Virus. J. Virol. 2010, 84, 9497–9504. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Faulkner, P.; Kuzio, J.; Williams, G.V.; Wilson, J.A. Analysis of P74, a PDV Envelope Protein of Autographa Californica Nucleopolyhedrovirus Required for Occlusion Body Infectivity in Vivo. J. Gen. Virol. 1997, 78, 3091–3100. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Kuzio, J.; Jaques, R.; Faulkner, P. Identification of P74, a Gene Essential for Virulence of Baculovirus Occlusion Bodies. Virology 1989, 173, 759–763. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kikhno, I.; Gutiérrez, S.; Croizier, L.; Croizier, G.; Ferber, M.L. Characterization of Pif, a Gene Required for the per Os Infectivity of Spodoptera Littoralis Nucleopolyhedrovirus. J. Gen. Virol. 2002, 83, 3013–3022. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Pijlman, G.P.; Pruijssers, A.J.P.; Vlak, J.M. Identification of Pif-2, a Third Conserved Baculovirus Gene Required for per Os Infection of Insects. J. Gen. Virol. 2003, 84, 2041–2049. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Fang, M.; Nie, Y.; Wang, Q.; Deng, F.; Wang, R.; Wang, H.; Wang, H.; Vlak, J.M.; Chen, X.; Hu, Z. Open Reading Frame 132 of Heliocoverpa Armigera Nucleopolyhedrovirus Encodes a Functional per Os Infectivity Factor (PIF-2). J. Gen. Virol. 2006, 87, 2563–2569. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ohkawa, T.; Washburn, J.O.; Sitapara, R.; Sid, E.; Volkman, L.E. Specific Binding of Autographa Californica M Nucleopolyhedrovirus Occlusion-Derived Virus to Midgut Cells of Heliothis virescens Larvae Is Mediated by Products of Pif Genes Ac119 and Ac022 but Not by Ac115. J. Virol. 2005, 79, 15258–15264. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Li, X.; Song, J.; Jiang, T.; Liang, C.; Chen, X. The N-Terminal Hydrophobic Sequence of Autographa Californica Nucleopolyhedrovirus PIF-3 Is Essential for Oral Infection. Arch. Virol. 2007, 152, 1851–1858. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Fang, M.; Nie, Y.; Harris, S.; Erlandson, M.A.; Theilmann, D.A. Autographa Californica Multiple Nucleopolyhedrovirus Core Gene Ac96 Encodes a Per Os Infectivity Factor (Pif-4). J. Virol. 2009, 83, 12569–12578. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Huang, H.; Wang, M.; Deng, F.; Wang, H.; Hu, Z. ORF85 of HearNPV Encodes the per Os Infectivity Factor 4 (PIF4) and Is Essential for the Formation of the PIF Complex. Virology 2012, 427, 217–223. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Green Version]

- Harrison, R.L.; Sparks, W.O.; Bonning, B.C. Autographa Californica Multiple Nucleopolyhedrovirus ODV-E56 Envelope Protein Is Required for Oral Infectivity and Can Be Substituted Functionally by Rachiplusia Ou Multiple Nucleopolyhedrovirus ODV-E56. J. Gen. Virol. 2010, 91, 1173–1182. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sparks, W.O.; Harrison, R.L.; Bonning, B.C. Autographa Californica Multiple Nucleopolyhedrovirus ODV-E56 Is a per Os Infectivity Factor but Is Not Essential for Binding and Fusion of Occlusion-Derived Virus to the Host Midgut. Virology 2011, 409, 69–76. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Nie, Y.; Fang, M.; Erlandson, M.A.; Theilmann, D.A. Analysis of the Autographa Californica Multiple Nucleopolyhedrovirus Overlapping Gene Pair Lef3 and Ac68 Reveals That AC68 Is a Per Os Infectivity Factor and That LEF3 Is Critical, but Not Essential, for Virus Replication. J. Virol. 2012, 86, 3985–3994. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Green Version]

- Liu, J.; Zhu, L.; Zhang, S.; Deng, Z.; Huang, Z.; Yuan, M.; Wu, W.; Yang, K. The Autographa Californica Multiple Nucleopolyhedrovirus Ac110 Gene Encodes a New per Os Infectivity Factor. Virus Res. 2016, 221, 30–37. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Javed, M.A.; Biswas, S.; Willis, L.G.; Harris, S.; Pritchard, C.; van Oers, M.M.; Donly, B.C.; Erlandson, M.A.; Hegedus, D.D.; Theilmann, D.A. Autographa Californica Multiple Nucleopolyhedrovirus AC83 Is a Per Os Infectivity Factor (PIF) Protein Required for Occlusion-Derived Virus (ODV) and Budded Virus Nucleocapsid Assembly as Well as Assembly of the PIF Complex in ODV Envelopes. J. Virol. 2017, 91, 2115–2131. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Green Version]

- Zhu, S.; Wang, W.; Wang, Y.; Yuan, M.; Yang, K. The Baculovirus Core Gene Ac83 Is Required for Nucleocapsid Assembly and Per Os Infectivity of Autographa Californica Nucleopolyhedrovirus. J. Virol. 2013, 87, 10573–10586. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Boogaard, B.; Evers, F.; van Lent, J.W.M.; van Oers, M.M. The Baculovirus Ac108 Protein Is a per Os Infectivity Factor and a Component of the ODV Entry Complex. J. Gen. Virol. 2019, 100, 669–678. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wang, X.; Shang, Y.; Chen, C.; Liu, S.; Chang, M.; Zhangh, N.; Hu, H.; Zhang, F.; Zhang, T.; Wang, Z.; et al. Baculovirus Per Os Infectivity Factor Complex: Components and Assembly. J. Virol. 2019, 93, 1–17. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Green Version]

- Garavaglia, M.J.; Miele, S.A.B.; Iserte, J.A.; Belaich, M.N.; Ghiringhelli, P.D. The Ac53, Ac78, Ac101, and Ac103 Genes Are Newly Discovered Core Genes in the Family Baculoviridae. J. Virol. 2012, 86, 12069–12079. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Wang, X.; Liu, X.; Makalliwa, G.A.; Li, J.; Wang, H.; Hu, Z.; Wang, M. Per Os Infectivity Factors: A Complicated and Evolutionarily Conserved Entry Machinery of Baculovirus. Sci. China Life Sci. 2017, 60, 806–815. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Peng, K.; van Lent, J.W.M.; Boeren, S.; Fang, M.; Theilmann, D.A.; Erlandson, M.A.; Vlak, J.M.; van Oers, M.M. Characterization of Novel Components of the Baculovirus Per Os Infectivity Factor Complex. J. Virol. 2012, 86, 4981–4988. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Boogaard, B.; van Oers, M.M.; van Lent, J.W.M. An Advanced View on Baculovirus per Os Infectivity Factors. Insects 2018, 9, 84. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Mu, J.; van Lent, J.W.M.; Smagghe, G.; Wang, Y.; Chen, X.; Vlak, J.M.; van Oers, M.M. Live Imaging of Baculovirus Infection of Midgut Epithelium Cells: A Functional Assay of per Os Infectivity Factors. J. Gen. Virol. 2014, 95, 2531–2539. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Green Version]

- Braunagel, S.C.; Williamson, S.T.; Saksena, S.; Zhong, Z.; Russell, W.K.; Russell, D.H.; Summers, M.D. Trafficking of ODV-E66 Is Mediated via a Sorting Motif and Other Viral Proteins: Facilitated Trafficking to the Inner Nuclear Membrane. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 2004, 101, 8372–8377. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Braunagel, S.; Summers, M. Molecular Biology of the Baculovirus Occlusion-Derived Virus Envelope. Curr. Drug Targets 2007, 8, 1084–1095. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Slack, J.M.; Dougherty, E.M.; Lawrence, S.D. A Study of the Autographa Californai Multiple Nucleopolyhedrovirus ODV Envelope Protein P74 Using a GFP Tag. J. Gen. Virol. 2001, 82, 2279–2287. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Peng, K.; van Lent, J.W.M.; Vlak, J.M.; Hu, Z.; van Oers, M.M. In Situ Cleavage of Baculovirus Occlusion-Derived Virus Receptor Binding Protein P74 in the Peroral Infectivity Complex. J. Virol. 2011, 85, 10710–10718. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Slack, J.M.; Lawrence, S.D.; Krell, P.J.; Arif, B.M. Trypsin Cleavage of the Baculovirus Occlusion-Derived Virus Attachment Protein P74 Is Prerequisite in per Os Infection. J. Gen. Virol. 2008, 89, 2388–2397. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Slack, J.M.; Lawrence, S.D.; Krell, P.J.; Arif, B.M. A Soluble Form of P74 Can Act as a per Os Infectivity Factor to the Autographa Californica Multiple Nucleopolyhedrovirus. J. Gen. Virol. 2010, 91, 915–918. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Song, J.; Wang, R.; Deng, F.; Wang, H.; Hu, Z. Functional Studies of per Os Infectivity Factors of Helicoverpa Armigera Single Nucleocapsid Nucleopolyhedrovirus. J. Gen. Virol. 2008, 89, 2331–2338. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Song, J.; Wang, X.; Hou, D.; Huang, H.; Liu, X.; Deng, F.; Wang, H.; Arif, B.M.; Hu, Z.; Wang, M. The Host Specificities of Baculovirus per Os Infectivity Factors. PLoS ONE 2016, 11, 1–12. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Green Version]

- Hsu, P.D.; Scott, D.A.; Weinstein, J.A.; Ran, F.A.; Konermann, S.; Agarwala, V.; Li, Y.; Fine, E.J.; Wu, X.; Shalem, O.; et al. DNA Targeting Specificity of RNA-Guided Cas9 Nucleases. Nat. Biotechnol. 2013, 31, 827–832. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Suenaga, T.; Kohyama, M.; Hirayasu, K.; Arase, H. Engineering Large Viral DNA Genomes Using the CRISPR-Cas9 System. Microbiol. Immunol. 2014, 58, 513–522. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Pazmiño-Ibarra, V.; Mengual-Martí, A.; Targovnik, A.M.; Herrero, S. Improvement of Baculovirus as Protein Expression Vector and as Biopesticide by CRISPR/Cas9 Editing. Biotechnol. Bioeng. 2019, 116, 2823–2833. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Cui, Y.; Xu, J.; Cheng, M.; Liao, X.; Peng, S. Review of CRISPR/Cas9 SgRNA Design Tools. Interdiscip. Sci. Comput. Life Sci. 2018, 10, 455–465. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wyman, C.; Kanaar, R. DNA Double-Strand Break Repair: All’s Well That Ends Well. Annu. Rev. Genet. 2006, 40, 363–383. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Vaughn, J.L.; Goodwin, R.H.; Tompkins, G.J.; McCawley, P. The Establishment of Two Cell Lines from the Insect Spodoptera Frugiperda (Lepidoptera; Noctuidae). In Vitro 1977, 13, 213–217. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Larkin, M.A.; Blackshields, G.; Brown, N.P.; Chenna, R.; McGettigan, P.A.; McWilliam, H.; Valentin, F.; Wallace, I.M.; Wilm, A.; Lopez, R.; et al. Clustal W and Clustal X Version 2.0. Bioinformatics 2007, 23, 2947–2948. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Green Version]

- Kumar, S.; Stecher, G.; Tamura, K. MEGA7: Molecular Evolutionary Genetics Analysis Version 7.0 for Bigger Datasets. Mol. Biol. Evol. 2016, 33, 1870–1874. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Green Version]

- Le, S.Q.; Gascuel, O. An Improved General Amino Acid Replacement Matrix. Mol. Biol. Evol. 2008, 25, 1307–1320. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Green Version]

- Crooks, G.E.; Hon, G.; Chandonia, J.-M.; Brenner, S.E. WebLogo: A Sequence Logo Generator. Genome Res. 2004, 14, 1188–1190. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Krogh, A.; Larsson, B.; Von Heijne, G.; Sonnhammer, E.L.L. Predicting Transmembrane Protein Topology with a Hidden Markov Model: Application to Complete Genomes. J. Mol. Biol. 2001, 305, 567–580. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Green Version]

- Ceroni, A.; Passerini, A.; Vullo, A.; Frasconi, P. DISULFIND: A Disulfide Bonding State and Cysteine Connectivity Prediction Server. Nucleic Acids Res. 2006, 34, W177–W181. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Green Version]

- Ferrè, F.; Clote, P. Disulfide Connectivity Prediction Using Secondary Structure Information and Diresidue Frequencies. Bioinformatics 2005, 21, 2336–2346. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- La Cour, T.; Kiemer, L.; Mølgaard, A.; Gupta, R.; Skriver, K.; Brunak, S. Analysis and Prediction of Leucine-Rich Nuclear Export Signals. Protein Eng. Des. Sel. 2004, 17, 527–536. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Green Version]

- Luckow, V.A.; Lee, S.C.; Barry, G.F.; Olins, P.O. Efficient Generation of Infectious Recombinant Baculoviruses by Site-Specific Transposon-Mediated Insertion of Foreign Genes into a Baculovirus Genome Propagated in Escherichia Coli. J. Virol. 1993, 67, 4566–4579. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Green Version]

- O’Reilly, D.R.; Miller, L.K.M.; Luckow, V.A. Baculovirus Expression Vectors: A Laboratory Manual; Oxford University Press: Oxford, UK, 1994. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Green, M.R.; Hughes, H.; Sambrook, J.; MacCallum, P. Molecular Cloning: A Laboratory Manual; Cold Spring Harbor Laboratory Press: New York, NY, USA, 2012; p. 1890. [Google Scholar]

- King, L.A.; Hitchman, R.; Possee, R.D. Recombinant Baculovirus Isolation. Methods Mol. Biol. 2016, 1350, 73–94. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mena, J.A.; Ramírez, O.T.; Palomares, L.A. Titration of Non-Occluded Baculovirus Using a Cell Viability Assay. Biotechniques 2003, 34, 260–264. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hughes, P.R.; Wood, H.A. A Synchronous Peroral Technique for the Bioassay of Insect Viruses. J. Invertebr. Pathol. 1981, 37, 154–159. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wu, W.; Wang, J.; Xie, F.; Long, Q.; Wang, X. Baculovirus P74 Gene Is a Species-Specific Gene. Acta Biochim. Biophys. Sin. 2003, 35, 834–840. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Makalliwa, G.A.; Wang, X.; Zhang, H.; Zhang, N.; Chen, C.; Li, J.; Deng, F.; Wang, H.; Wang, M.; Hu, Z. HearNPV Pseudotyped with PIF1, 2, and 3 from MabrNPV: Infectivity and Complex Stability. Virol. Sin. 2018, 33, 187–196. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wang, Y.; Kleespies, R.G.; Huger, A.M.; Jehle, J.A. The Genome of Gryllus Bimaculatus Nudivirus Indicates an Ancient Diversification of Baculovirus-Related Nonoccluded Nudiviruses of Insects. J. Virol. 2007, 81, 5395–5406. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Green Version]

- Fu, S.-C.; Fung, H.Y.J.; Cağatay, T.; Baumhardt, J.; Chook, Y.M. Correlation of CRM1-NES Affinity with Nuclear Export Activity. Mol. Biol. Cell. 2018, 29, 2037–2044. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yao, L.; Zhou, W.; Xu, H.; Zheng, Y.; Qi, Y. The Heliothis Armigera Single Nucleocapsid Nucleopolyhedrovirus Envelope Protein P74 Is Required for Infection of the Host Midgut. Virus Res. 2004, 104, 111–121. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Huang, Z.; Pan, M.; Zhu, S.; Zhang, H.; Wu, W.; Yuan, M.; Yang, K. The Autographa Californica Multiple Nucleopolyhedrovirus Ac83 Gene Contains a Cis-Acting Element That Is Essential for Nucleocapsid Assembly. J. Virol. 2017, 91, e02110–e02116. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Green Version]

- Jiao, Y.; Wang, J.; Deng, R.; Yu, X.; Wang, X. AcMNPV-MiR-3 Is a MiRNA Encoded by Autographa Californica Nucleopolyhedrovirus and Regulates the Viral Infection by Targeting Ac101. Virus Res. 2019, 267, 49–58. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Miele, S.A.B.; Cerrudo, C.S.; Parsza, C.N.; Nugnes, M.V.; Mengual Gómez, D.L.; Belaich, M.N.; Ghiringhelli, P.D. Identification of Multiple Replication Stages and Origins in the Nucleopolyhedrovirus of Anticarsia Gemmatalis. Viruses 2019, 11, 648. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Green Version]

| Primer | Sequence (5′ to 3′) |

|---|---|

| FwP74seq | GGTTTTAACAGCCGTCGATTTA |

| RvP74seq | TAAGATGCATTTGTTGTCGAGC |

| pFwp74Ac | GAAGATCTATGGCGGTTTTAACAG |

| pRevp74Ac | CCCAAGCTTAAAATAACAAATCAATTG |

| pRevBamAc | TAACCGAACGGATCCCATAGCGC |

| pFwBamAc | GCGCTATGGGATCCGTTCGGTTA |

| pFwP74Se | ATCAGATCTGCTATGCTCACTTTTGTAGAC |

| pRvP74Se | ATCAAGCTTATTCCGAATAGAGATTGTCGTAC |

| pFwP74Ha | ATCAGATCTTTCATGTCGAATATCATTTATATAC |

| pRvP74Ha | ATCAAGCTTATGTGTATAAATTGTGGTACC |

| FwMe53 | GCTTTGAAATGCACAACG |

| P74 | AcMNPV | SeMNPV | HearSNPV | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| AcMNPV | 100 | 55 | 52 | |

| Complete | SeMNPV | 82 | 100 | 55 |

| HearSNPV | 82 | 82 | 100 | |

| AcMNPV | 100 | 59 | 57 | |

| Nt | SeMNPV | 85 | 100 | 59 |

| HearSNPV | 83 | 84 | 100 | |

| AcMNPV | 100 | 46 | 42 | |

| Ct | SeMNPV | 78 | 100 | 46 |

| HearSNPV | 77 | 77 | 100 |

Publisher’s Note: MDPI stays neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations. |

© 2021 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Nugnes, M.V.; Targovnik, A.M.; Mengual-Martí, A.; Miranda, M.V.; Cerrudo, C.S.; Herrero, S.; Belaich, M.N. The Membrane-Anchoring Region of the AcMNPV P74 Protein Is Expendable or Interchangeable with Homologs from Other Species. Viruses 2021, 13, 2416. https://doi.org/10.3390/v13122416

Nugnes MV, Targovnik AM, Mengual-Martí A, Miranda MV, Cerrudo CS, Herrero S, Belaich MN. The Membrane-Anchoring Region of the AcMNPV P74 Protein Is Expendable or Interchangeable with Homologs from Other Species. Viruses. 2021; 13(12):2416. https://doi.org/10.3390/v13122416

Chicago/Turabian StyleNugnes, María Victoria, Alexandra Marisa Targovnik, Adrià Mengual-Martí, María Victoria Miranda, Carolina Susana Cerrudo, Salvador Herrero, and Mariano Nicolás Belaich. 2021. "The Membrane-Anchoring Region of the AcMNPV P74 Protein Is Expendable or Interchangeable with Homologs from Other Species" Viruses 13, no. 12: 2416. https://doi.org/10.3390/v13122416