Let’s Talk about Circular Economy: A Qualitative Exploration of Consumer Perceptions

Abstract

:1. Introduction

1.1. Circular Economy: Rethinking Both the Supply and Demand Sides

1.2. Consumer Perspective on Circular Economy

1.3. Aim of This Study

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Procedure

2.2. Participant Selection

2.3. Measures

2.4. Data Analysis

3. Results

3.1. Associations with the Circular Economy as a Term

3.2. Ranking the Circular Economy and Related Terms

3.3. Perceptions of Food-Related Examples of a CE

3.3.1. Motives and Advantages of Food-Related Examples of a CE

3.3.2. Objections and Disadvantages of Food-Related Examples of a CE

3.3.3. Consumer Perceptions of Behaviour and Participation in the CE

3.4. General Perceptions of the Focus Group Discussion on the CE

4. Discussion

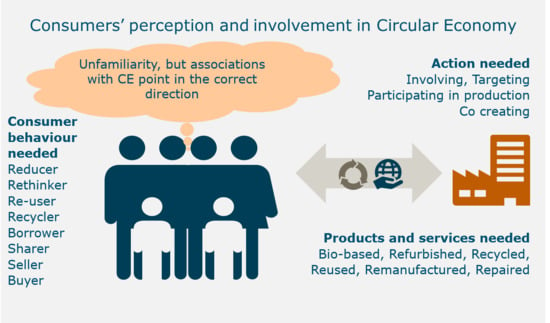

4.1. Key Observations on Consumer Attitudes, Perceptions and Behaviours

4.2. Implications and Recommendations for Consumer Involvement

4.3. Limitations and Future Research

5. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

Appendix A. Description of the Practice Cases

| Gentlemen farming: Producing sustainable food jointly. Several (approximately 200) families share a farm and own it jointly. It is a partnership where citizens invest money (in land or buildings). Together, they decide what they want to eat from their farm, what is planted, and if/which animals should be kept. They employ a farmer whose job it is to take care of the land and other daily activities on the farm. In case the families want to help with harvesting, this is possible. |

| Circular pig: In this example, pigs are kept on a farm close to or in a city and are fed with bostel, a residual product from breweries. As such, the pigs eat (food) waste from the city, including waste from bakeries, supermarkets and cheese farmers. Local residents also help to keep the pigs. In the end, when the pigs are slaughtered, the pig meat could be eaten during a neighbourhood activity. |

| Home takeaway: Sharing meals with your neighbours. By means of an online platform, people are able to share meals. You can either prepare meals or pick them up in the neighbourhood. It is possible to share with and meet other people. The platform was initially created to facilitate social contact by having chance meetings. |

| Avoiding waste factory: New products are made from foods that otherwise would be waste. The basis of the avoiding waste factory is upcycling food waste into new, edible products. Such factories make use of residual streams such as tomatoes, peppers, mushrooms or potatoes and produce soup or a basic sauce for pizzas and pasta. |

| Paper-like box made from manure: Manure contains fibres that can be used to produce paper similar to sheets of paper or boxes as packaging for, e.g., tomatoes. The fibres come from the grass that cows eat, which is the raw material for paper and cardboard (this process will not work for manure of pigs and chickens because they do not eat grass). |

| Bio-based bag made from sewage water: In the past, sludge was a residual product that went to waste incineration, but now it is used as raw material for (biodegradable) bioplastic. This plastic can be used for a wide variety of plastic products, such as plastic bags. |

| Peerby loan platform: This is an online platform where you can borrow and share items that you need instead of buying them, such as a hand-held blender or an electric drill. This initiative is illustrated by the following sentences: “Sometimes you just need something you do not have at home. Why would you buy it if you can borrow it from your neighbours?” and “An electric drill is used for 13 min during its lifespan. Why not share it if it is just lying around somewhere collecting dust?!” |

References

- Repo, P.; Anttonen, M.; Mykkänen, J.; Lammi, M. Lack of congruence between european citizen perspectives and policies on circular economy. Eur. J. Sustain. Dev. 2018, 7, 249–264. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Towards the Circular Economy, Economic and Business Rationale for an Accelerated Transition; EMF (Ellen MacArthur Foundation): Cowes, UK, 2013.

- Kirchherr, J.; Reike, D.; Hekkert, M. Conceptualizing the circular economy: An analysis of 114 definitions. Resour. Conserv. Recycl. 2017, 127, 221–232. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Camacho-Otero, J.; Boks, C.; Pettersen, I.N. Consumption in the Circular Economy: A Literature Review. Sustainability 2018, 10, 2758. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Maitre-Ekern, E.; Dalhammar, C. Towards a hierarchy of consumption behaviour in the circular economy. Maastricht J. Eur. Comp. Law 2019, 26, 394–420. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kirchherr, J.; Piscicelli, L.; Bour, R.; Kostense-Smit, E.; Müller, J.; Huibrechtse-Truijens, A.; Hekkert, M. Barriers to the Circular Economy: Evidence from the European Union (EU). Ecol. Econ. 2018, 150, 264–272. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Van Weelden, E.; Mugge, R.; Bakker, C. Paving the way towards circular consumption: Exploring consumer acceptance of refurbished mobile phones in the Dutch market. J. Clean. Prod. 2016, 113, 743–754. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Vehmas, K.; Raudaskoski, A.; Heikkilä, P.; Harlin, A.; Mensonen, A. Consumer attitudes and communication in circular fashion. J. Fash. Mark. Manag. Int. J. 2018, 22, 286–300. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Spangenberg, J.H.; Lorek, S. Sufficiency and consumer behaviour: From theory to policy. Energy Policy 2019, 129, 1070–1079. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Edbring, E.G.; Lehner, M.; Mont, O. Exploring consumer attitudes to alternative models of consumption: Motivations and barriers. J. Clean. Prod. 2016, 123, 5–15. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Muranko, Z.; Andrews, D.; Newton, E.J.; Chaer, I.; Proudman, P. The Pro-Circular Change Model (P-CCM): Proposing a framework facilitating behavioural change towards a Circular Economy. Resour. Conserv. Recycl. 2018, 135, 132–140. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Roodhuyzen, D.; Luning, P.; Fogliano, V.; Steenbekkers, L. Putting together the puzzle of consumer food waste: Towards an integral perspective. Trends Food Sci. Technol. 2017, 68, 37–50. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Quested, T.; Marsh, E.; Stunell, D.; Parry, A. Spaghetti soup: The complex world of food waste behaviours. Resour. Conserv. Recycl. 2013, 79, 43–51. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Grunert, K.G.; van Trijp, H.C.M. Consumer-oriented new product development. Encycl. Agric. Food Syst. 2014, 2, 375–386. [Google Scholar]

- Dagevos, H.; Sijtsema, S.J.; Reinders, M.J.; Meeusen, M. The Roles of Citizens and Consumers. In Technical Options for Retrofitting Energy Industries with Bioenergy: A Handbook for Non-Technicians; Rutz, R., Janssen, D., Eds.; WIP Renewable Energies: München, Germany, 2019; pp. 11–19, forthcoming. [Google Scholar]

- De Jesus, A.; Mendonça, S. Lost in Transition? Drivers and Barriers in the Eco-innovation Road to the Circular Economy. Ecol. Econ. 2018, 145, 75–89. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Guerrero, L.X.J. New Approaches to Focus Groups, in Methods in Consumer Research. New Approaches to Classic Methods. In Series in Food Science, Technology and Nutrition; Woodhead Publishing: Sawston, UK, 2018. [Google Scholar]

- Mesías, F.J.; Escribano, M. Projective Techniques, in Methods in Consumer Research, Volume 1 New Approaches to Classic Methods. In Series in Food Science, Technology and Nutrition; Woodhead Publishing: Sawston, UK, 2018; pp. 79–102. [Google Scholar]

- Sijtsema, S.J.; Onwezen, M.C.; Reinders, M.J.; Dagevos, H.; Partanen, A.; Meeusen, M. Consumer perception of bio-based products—An exploratory study in 5 European countries. NJAS Wagening. J. Life Sci. 2016, 77, 61–69. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Krueger, R.A.; Casey, M.A. Focus Groups: A Practical Guide for Applied Research; Sage Publications: Thousand Oaks, CA, USA, 2014. [Google Scholar]

- Haan, M.; Konijn, E.A.; Burgers, C.; Eden, A.; Brugman, B.C.; Verheggen, P.P. Identifying sustainable population segments using a multi-domain questionnaire: A five factor sustainability scale. Soc. Mark. Q. 2018, 24, 264–280. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Verain, M.C.; Bartels, J.; Dagevos, H.; Sijtsema, S.J.; Onwezen, M.C.; Antonides, G. Segments of sustainable food consumers: A literature review. Int. J. Consum. Stud. 2012, 36, 123–132. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Phau, S.; Vos, J.; Dammer, L.; Arendt, O. Public Perception of Bio-Based Products; European Union’s: Brussels, Belgium, 2017. [Google Scholar]

- Trope, Y.; Liberman, N. Temporal construal and time-dependent changes in preference. J. Pers. Soc. Psychol. 2000, 79, 876–889. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Heidbreder, L.M.; Bablok, I.; Drews, S.; Menzel, C. Tackling the plastic problem: A review on perceptions, behaviors, and interventions. Sci. Total Environ. 2019, 668, 1077–1093. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

© 2019 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Sijtsema, S.J.; Snoek, H.M.; van Haaster-de Winter, M.A.; Dagevos, H. Let’s Talk about Circular Economy: A Qualitative Exploration of Consumer Perceptions. Sustainability 2020, 12, 286. https://doi.org/10.3390/su12010286

Sijtsema SJ, Snoek HM, van Haaster-de Winter MA, Dagevos H. Let’s Talk about Circular Economy: A Qualitative Exploration of Consumer Perceptions. Sustainability. 2020; 12(1):286. https://doi.org/10.3390/su12010286

Chicago/Turabian StyleSijtsema, Siet J., Harriëtte M. Snoek, Mariët A. van Haaster-de Winter, and Hans Dagevos. 2020. "Let’s Talk about Circular Economy: A Qualitative Exploration of Consumer Perceptions" Sustainability 12, no. 1: 286. https://doi.org/10.3390/su12010286