Key Issues in Slow Fashion: Current Challenges and Future Perspectives

Abstract

:1. Introduction

2. Slow Fashion: Current Knowledge and Challenges

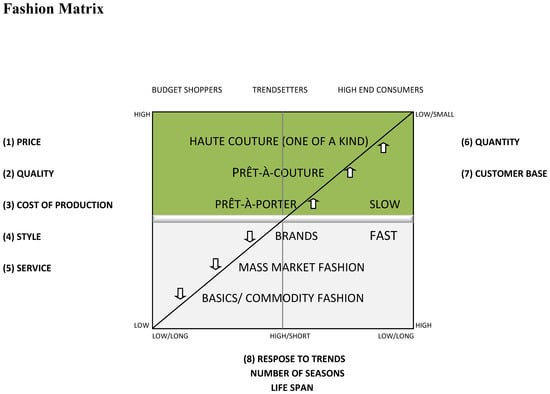

3. Fashion Matrix

3.1. Price

3.2. Quality

3.3. Cost of Production

3.4. Style

3.5. Service

3.6. Quantity

3.7. Customers

3.8. Response to Trends

3.9. Networks

4. Discussion

Author Contributions

Funding

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Thompson, H.; Whittington, N. Remake It Clothes: The Essential Guide to Resourceful Fashion: With over 500 Tricks, Tips and Inspirational Designs, 1st ed.; Thames & Hudson: London, UK, 2012; p. 272. ISBN 9780500516324. [Google Scholar]

- Fletcher, K. Slow Fashion: An Invitation for Systems Change. Fash. Pract. J. Des. Creat. Process Fash. Ind. 2010, 2, 259–266. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Clark, H. Slow + Fashion—An Oxymoron—Or a Promise for the Future …? Fash. Theory J. Dress Body Cult. 2008, 12, 427–446. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Leslie, D.; Brail, S.; Hunt, M. Crafting an Antidote to Fast Fashion: The Case of Toronto’s Independent Fashion Design Sector. Growth Chang. 2014, 45, 222–239. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Thomas, S. From “Green Blur” to Ecofashion: Fashioning an Eco-Lexicon. Fash. Theory 2015, 12, 525–539. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Holt, T. Is the Time Right for Slow Fashion? Christian Science Monitor: Boston, MA, USA, 2009. Available online: http://www.csmonitor.com/The-Culture/2009/0210/p17s01-lign.html (accessed on 29 May 2018).

- Doeringer, P.; Crean, S. Can Fast Fashion Save the US Apparel Industry? Socio Econ. Rev. 2006, 4, 353–377. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Watson, M.Z.; Yan, R. An Exploratory Study of the Decision Processes of Fast Versus Slow Fashion Consumers. J. Fash. Market. Manag. Int. J. 2013, 17, 141–159. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pookulangara, S.; Shephard, A. Slow Fashion Movement: Understanding Consumer Perceptions—An Exploratory Study. J. Retail. Consum. Serv. 2013, 20, 200–206. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fletcher, K. Slow Fashion. Ecologist 2007, 37, 61. [Google Scholar]

- Freestone, O.M.; McGoldrick, P.J. Motivations of the Ethical Consumer. J. Bus. Ethics 2008, 79, 445–467. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cachon, G.P.; Swinney, R. The Value of Fast Fashion: Quick Response, Enhanced Design, and Strategic Consumer Behavior. Manag. Sci. 2011, 57, 778–795. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Fashion Revolution. Garment Worker Diaries the Lives and Wages of Garment Workers. 2018. Available online: http://workerdiaries.org/ (accessed on 28 May 2018).

- Jung, S.; Jin, B. From Quantity to Quality: Understanding Slow Fashion Consumers for Sustainability and Consumer Education. Int. J. Consum. Stud. 2016, 40, 410–421. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Litavcova, E.; Bucki, R.; Stefko, R.; Suchánek, P.; Jenčová, S. Consumer’s Behaviour in East Slovakia after Euro Introduction during the Crisis. Prague Econ. Pap. 2015, 24, 332–353. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Gam, H.J.; Cao, H.; Farr, C.; Heine, L. C2CAD: A Sustainable Apparel Design and Production Model. Int. J. Cloth. Sci. Technol. 2009, 21, 166–179. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pookulangara, S.; Shephard, A.; Mestres, J. University Community’s Perception of Sweatshops: A Mixed Method Data Collection. Int. J. Consum. Stud. 2011, 35, 476–483. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hyunsook, K.; Choo, H.J.; Yoon, N. The Motivational Drivers of Fast Fashion Avoidance. J. Fash. Market. Manag. Int. J. 2013, 17, 243–260. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Carrigan, M.; Attalla, A. The Myth of the Ethical Consumer—Do Ethics Matter in Purchase Behaviour? J. Consum. Market. 2001, 18, 560–578. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bhaduri, G.; Ha-Brookshire, J.E. Do Transparent Business Practices Pay? Exploration of Transparency and Consumer Purchase Intention. Cloth. Text. Res. J. 2011, 29, 135–149. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Brown, R. Everlane’s Take on Supply and Demand. Wwd 2013, 206. Available online: http://wwd.com/accessories-news/handbags/everlanes-take-on-supply-and-demand-7326470/ (accessed on 29 May 2018).

- Stefko, R.; Fedorko, I.; Bacik, R.; Fedorko, R. An Analysis of Perceived Topicality of Website Content Influence in Terms of Reputation Management. Pol. J. Manag. Stud. 2015, 12, 177–185. [Google Scholar]

- Karr, A.J. Fast-Fashion Retailers Outpace Competitors. Women’s Wear Daily 2009, 26, 14. [Google Scholar]

- Stefko, R.; Bacik, R.; Fedorko, I. Facebook Content Analysis of Banks Operating on Slovak Market. Pol. J. Manag. Stud. 2014, 10, 145–152. [Google Scholar]

- Stefko, R.; Fedorko, R.; Bacik, R. The Role of E-marketing Tools in Constructing the Image of a Higher Education Institution. Procedia Soc. Behav. Sci. 2015, 175, 431–438. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- O’Brien, C. The Emergence of the Social Media Empowered Consumer. Irish Market. Rev. 2011, 21, 32–40. [Google Scholar]

- Ertekin, Z.O.; Atik, D. Sustainable Markets Motivating Factors, Barriers, and Remedies for Mobilization of Slow Fashion. J. Macromarket. 2014, 35, 53–69. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Greblikaite, J.; Gerulaitiene, N.; Sroka, W. From Traditional Business to Social One: New Possibilities for Entrepreneurs in Rural Areas. In Proceedings of the International Scientific Conference Rural Development, Jelgava, Latvia, 9–11 May 2018. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Stefko, R.; Kiralova, A.; Mudrik, M. Strategic Marketing Communication in Pilgrimage Tourism. Procedia Soc. Behav. Sci. 2015, 175, 423–430. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Stefko, R.; Fedorko, R.; Bacik, R. Website Content Quality in Terms of Perceived Image of Higher Education Institution. Pol. J. Manag. Stud. 2015, 13, 153–163. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ha-Brookshire, J.E.; Hodges, N.N. Socially Responsible Consumer Behavior? Exploring Used Clothing Donation Behavior. Cloth. Text. Res. J. 2009, 27, 179–196. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Morgan, L.R.; Birtwistle, G. An Investigation of Young Fashion Consumers’ Disposal Habits. Int. J. Consum. Stud. 2009, 33, 190–198. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Johansson, E. Slow Fashion: The Answer for a Sustainable Fashion Industry? Master’s Thesis, University of Borås, Borås, Sweden, 2010. [Google Scholar]

- Bly, S.; Gwozdz, W.; Reisch, L. Exit from High Street: An Exploratory Study of Sustainable Fashion Consumption Pioneers. Int. J. Consum. Stud. 2015, 39, 125–135. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Guillen-Royo, M.; Wilhite, H.L. Wellbeing and Sustainable Consumption. In Global Handboook of Quality of Life; Springer: Dordrecht, The Netherlands, 2015; pp. 301–316. [Google Scholar]

- Barnes, L.; Lea-Greenwood, G. Fast Fashioning the Supply Chain: Shaping the Research Agenda. J. Fash. Market. Manag. Int. J. 2006, 10, 259–271. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wood, Z. Slow Fashion: As Times Get Hard and Green Consciousness Grows, Lasting Styles Made with Organic and Fair Trade Materials Are Gaining in Popularity; The Observer: London, UK, 2009; Available online: http://eartheasy.com/blog/2009/01/slow-fashion (accessed on 15 October 2017).

- Law, K.M.; Zhang, Z.; Leung, C. Fashion Change and Fashion Consumption: The Chaotic Perspective. J. Fash. Market. Manag. 2004, 8, 362–374. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- McAfee, A.; Dessain, V.; Sjoman, A. Zara: IT for Fast Fashion; Harvard Business School: Boston, MA, USA, 2009; pp. 1–23. [Google Scholar]

- Mitkus, T. Internationalization Process of Creative Industries: Tendencies, Problems and Challenges. Forum Sci. Oecon. 2016, 4, 27–38. [Google Scholar]

- Bruneel, J.; Ratinho, T.; Clarysse, B.; Groen, A.J. The Evolution of Business Incubators: Comparing Demand and Supply of Business Incubation Services across Different Incubator Generations. Technovation 2012, 32, 110–121. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hansen, M.T.; Chesbrough, H.W.; Nohria, N.; Sull, D.N. Networked Incubators: Hothouses of the New Economy. Harv. Bus. Rev. 2012, 78, 74. [Google Scholar]

- Yli-Renko, H.; Autio, E.; Sapienza, H.J. Social Capital, Knowledge Acquisition, and Knowledge Exploitation in Young Technology-Based Firms. Strateg. Manag. J. 2001, 22, 587–613. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Scillitoe, J.L.; Chakrabarti, A.K. The Role of Incubator Interactions in Assisting New Ventures. Technovation 2010, 30, 155–167. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Stefko, R.; Steffek, V. A Study of Creative Industry Entrepreneurial Incubation. Pol. J. Manag. Stud. 2017, 15, 250–261. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lalkaka, R.; Thorburn, L.; Bishop, J. Business Incubators in Economic Development: An Initial Assessment in Industrializing Countries. Prometheus 1998, 16, 98–101. [Google Scholar]

- Chwistecka-Dudek, H. Corporate Social Responsibility: Supporters vs. Opponents of the Concept. Forum Sci. Oecon. 2016, 4, 171–180. [Google Scholar]

| Factors * | Current Knowledge | Future Perspectives and Challenges |

|---|---|---|

| 1. Price |

|

|

| 2. Quality |

|

|

| 3. Cost of Production |

|

|

| 4. Style |

|

|

| 5. Service |

|

|

| 6. Quantity |

|

|

| 7. Customers |

|

|

| 8. Response to Trends |

|

|

© 2018 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Štefko, R.; Steffek, V. Key Issues in Slow Fashion: Current Challenges and Future Perspectives. Sustainability 2018, 10, 2270. https://doi.org/10.3390/su10072270

Štefko R, Steffek V. Key Issues in Slow Fashion: Current Challenges and Future Perspectives. Sustainability. 2018; 10(7):2270. https://doi.org/10.3390/su10072270

Chicago/Turabian StyleŠtefko, Róbert, and Vladimira Steffek. 2018. "Key Issues in Slow Fashion: Current Challenges and Future Perspectives" Sustainability 10, no. 7: 2270. https://doi.org/10.3390/su10072270