Utilization of Spirituality and Spiritual Care in Nursing Practice in Public Hospitals in KwaZulu-Natal, South Africa

Abstract

:1. Introduction

The Conceptual Framework

2. Literature Review

2.1. Spirituality Defined

2.2. Nurses Views on Spirituality and Spiritual

2.3. Spiritual Care Activities in Patient Care

2.3.1. Prayer

2.3.2. Therapeutic Touch

2.3.3. Privacy for Self-Transcendental Reflection

2.3.4. Empathic Listening and Being Present

3. Research Methodology

3.1. Design

3.2. Validity and Reliability

3.3. Ethical Considerations

3.4. Data Collection and Analysis

4. Findings

4.1. Demographic Data Was Related to Age, Gender, Race and Years of Experience

4.2. Nurses Personal Spiritual/Religious Orientation

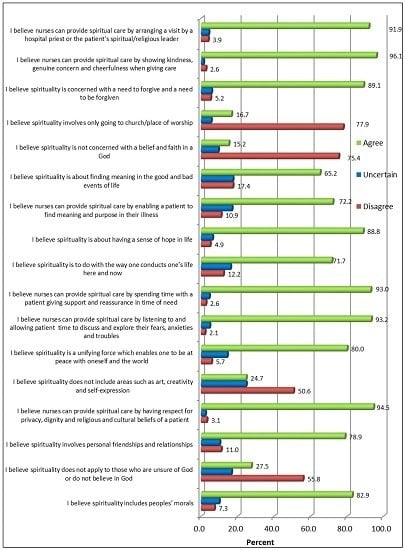

4.3. The Role of Spirituality and Spiritual Care in Nursing Practice

5. Discussion

5.1. Role of Spirituality and Spiritual Care in Nursing Practice

5.2. Salience of Spirituality and Spiritual Care to Patients

6. Conclusions

Acknowledgments

Author Contributions

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Wilfred McSherry, and Steve Jamieson. “An online survey of nurses’ perception of spirituality and spiritual care.” Journal of Clinical Nursing 20 (2010): 1757–67. Available online: http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/21385257 (accessed on 13 September 2013). [Google Scholar]

- Arleen Barlow. “Spirituality in nursing.” School Nursing News, 2011. Available online: http://allnurses.com/showthread.php (accessed on 17 February 2012). [Google Scholar]

- Linda L. Dunn. “Spirituality and Nursing: Personal Responsibility.” Journal of Rural Nursing and Health Care 8 (2012): 3–4. Available online: http:/mobile.journal./ww.com/hnpjournal/-layouts/ (accessed on 21 September 2013). [Google Scholar]

- Sarah N. Mahlungulu, and Leana R. Uys. “Spirituality in nursing: an analysis of the concept.” Curationis 27 (2004): 15–26. Available online: http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/m/pubmed/15974016/ (accessed on 18 September 2013). [Google Scholar]

- Denise Miner-Williams. “Putting a puzzle together: Making spirituality meaningful for nursing using an evolving theoretical framework.” Journal of Clinical Nursing 15 (2006): 811–21. Available online: http://10.1111/j1365-2702.2006.01351.x (accessed on 13 September 2013). [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Patricia E. Mahon Graham. “Nursing Students’ Perception of How Prepared They Are to Assess Patient’s Spiritual Needs.” Ed.D. Thesis, College of Saint Mary, Omaha, NE, USA, May 2008. [Google Scholar]

- Jean Watson. “Holistic nursing and caring. A value based approach.” Journal of Japan Academy of Nursing Science 22 (2002): 69–74. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Marg G. Hutchinson. “Holism and Spiritual Care in Practice.” 1998. Available online: http://members.tripod.com/marg_hutchison/nurse-4.html (accessed on 17 September 2013).

- Viktor Emil Frankl. Man’s Search for Meaning: An Introduction to Logotherapy, 2nd ed. New York: Simon and Schuster, 2006. [Google Scholar]

- Christina M. Puchalski. “The role of spirituality in health care.” Baylor University Medical Centre Proceedings 14 (2001): 352–57. [Google Scholar]

- Theris A. Touhy. “Nurturing hope and spirituality in nursing home.” Holistic Nursing Practice 15 (2001): 45–56. Available online: http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/m/pubmed/12120495/ (accessed on 18 October 2013). [Google Scholar]

- Loralee Sessanna, Deborah S. Finnell, Meghan Underhill, Yu-Ping Chang, and Hsi-Ling Peng. “Measures assessing spirituality as more than religiosity: A methodological review of nursing and health related literature.” Journal of Advanced Nursing 67 (2010): 1677–94. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Anita E. Molzahn, and Laurene Sheilds. “Why is it so hard to talk about spirituality? ” The Canadian Nursing Journal 101 (2008): 25. Available online: http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/m/pubmed/18286982 (accessed on 18 October 2013). [Google Scholar]

- Elizabeth O’Connell, and Margaret Landers. “The importance of critical care nurses’ behaviours as perceived by nurses and relatives.” Intensive Critical Care Nursing 24 (2008): 349–52. Available online: http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/m/pubmed/18499460/ (accessed on 17 October 2013). [Google Scholar]

- John Swinton, and Stephen Pattison. “Moving beyond clarity: A thin, vague and useful understanding of spirituality in nursing care.” Nursing Philosophy 11 (2010): 226–37. Available online: http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/m/pubmed/20840134/ (accessed on 18 September 2013). [Google Scholar]

- Madeline M. Maier-Lorentz. “The Importance of Prayer for Mind/Body Healing.” Nursing Forum 39 (2004): 23–32. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Michele Sloma. “Impact of Nursing Models in a Professional Environment: Linking Spiritual End of Life Care to Nursing Theory.” International Journal of Healing and Care, 2011. Available online: http://www.hospicemardelplata.org/documentos/Morir%20en%20casa%20o%20en%20el%20hospital.pdf (accessed on 18 September 2013). [Google Scholar]

- Lucia Thornton. “Holistic Nursing: A way of Being, A Way of Living, A way of Practice.” Holistic Nursing Practice 19 (2005): 106–15. Available online: http://www.ahna.org/AboutUs/whatisHolisticnursing/ (accessed on 10 September 2013). [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Linda S. Rieg, Carolyn H. Mason, and Kelly Preston. “Spiritual Care: Practical Guidelines for Rehabilition Nurses.” Rehabilitation Nursing 31 (2006): 249–56. Available online: http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/m/pubmed/17133926/ (accessed on 18 September 2013). [Google Scholar]

- Andrew A. Eric, Eric C. W. Kwong, Frances K. Y. Wong, and Elsa S. W. Tsang. “A review of the concept of spirituality and spiritual assessment tools.” Macau Journal of Nursing 6 (2007): 23–27. [Google Scholar]

- Joy Penman. “Motivations driving spiritual engagement based on a phenomenological study of spirituality among palliative care clients and caregivers.” World Journal of Nursing Education and Practice 2 (2012): 135–47. Available online: www.sciedu.ca/journal/index.php/ (accessed on 20 September 2013). [Google Scholar]

- Belinda Deal. “Pilot Study of Nurses’ Experience of Giving Spiritual Care.” The Qualitative Report 15 (2010): 852–63. Available online: http://eric.ed.gov/?id=Ej896174 (accessed on 10 September 2013). [Google Scholar]

- Sandra Courtney Sellers, and Barbara A. Haag. “Spiritual Nursing Interventions.” Journal of Holistic Nursing 16 (1998): 338–54. Available online: http://m.jhn.sagepub.com/content/16/3/338.ful.pdf (accessed on 21 October 2013). [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Moon Fai Chan. “Factors affecting nursing staff in practising spiritual care.” Journal of Clinical Nursing 16 (2009): 2128–36. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Belinda Deal. “The Lived Experience of Giving Spiritual Care.” Ph.D. Thesis, Woman Graduate University of Denton, Denton, TX, USA, December 2008. [Google Scholar]

- Belinda Deal, and Jane S. Grassley. “The Lived Experience of Giving Spiritual Care: A Phenomenological Study of Nephrology Nurses Working in Acute and Chronic Haemodialysis settings.” Nephrology Nursing Journal 39 (2012): 471–81. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Masoud Fallahi Khoshknab, Monir Mazaheri, Sadat S. B. Maddah, and Mehdi Rahgozar. “Validation and reliability test of Persian version of The Spirituality and Spiritual Care rating Scale (SSCRS).” Journal of Clinical Nursing 19 (2010): 2939–41. Available online: http://10.5402/2011/534803 (accessed on 13 September 2013). [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lodovico Balducci. “Suffering and Spirituality: Analysis of Living Experiences.” Journal of Pain and Symptom Management 42 (2011): 479–86. Available online: http://dutlib.dut.ac.za:2056/science/article (accessed on 12 September 2013). [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Waheedha Emmamally. “Demystifying Spiritual Care in Nursing.” Nursing Update 38 (2013): 24–25. [Google Scholar]

- Lynn Clark Callister, A. Elaine Bond, Gerry Matsumura, and Sandra Mangum. “Threading spirituality throughout nursing education.” Holistic Nursing Practice 18 (2004): 160–66. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Gabriel Kiley. “Nursing schools deans view spirituality as a core competency.” Catholic Health World 24 (2008): 1–2. Available online: https://www.chausa.org/hp (accessed on 17 September 2013). [Google Scholar]

- Arndt Büssing, and Harold G. Koenig. “Spiritual Needs of Patients with Chronic Disease.” Religions: Spiritual and Health Journal 1 (2010): 18–27. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Elizabeth Johnston Taylor. “Nurses caring for the spirit: Patients with cancer and family/caregivers expectations.” Oncology Nursing Forum 30 (2007): 585–90. Available online: http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/m/pubmed/12861319/ (accessed on 18 September 2013). [Google Scholar]

- Cynthia I. Shores. “Spiritual Perspectives of Nursing Students.” Nursing Education Perspectives 31 (2010): 8–11. Available online: http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/20397473 (accessed on 17 September 2013). [Google Scholar]

- Karen S. Dunn, and Ann L. Horgas. “The prevalence of prayer as a spiritual self-care modality in elders.” Journal of Holistic Nursing 18 (2000): 337–51. Available online: http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/m/pubmed/11847791/ (accessed on 18 October 2013). [Google Scholar]

- Harold G. Koenig. “Research on Religion, Spirituality and Mental Health: A Review.” Canadian Journal of Psychiatry 54 (2009): 283–91. Available online: http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/m/pubmed/19497160/ (accessed on 17 October 2013). [Google Scholar]

- Michael J. Balboni, Amenah Babar, Jennifer Dillinger, Andrea C. Phelps, Emily George, Susan D. Block, and Lisa Kachnic. “’It Depends’: Viewpoints of Patients, Physicians, and Nurses on Patient-Practitioner Prayer in the Setting of Advanced Cancer.” Journal of Pain and Symptom Management 41 (2011): 836–47. Available online: http://dut.summon.serialssolutions.com (accessed on 17 September 2013). [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- G. Hussein Rassool. “The crescent of Islam: Healing, nursing and the spiritual dimension. Some consideration to the understanding of the Islamic perception of caring.” Journal of Advanced Nursing 32 (2000): 1476–80. Available online: http://onlinelibrary.wiley.com/doi/10.1046/j.1365-2648.2000.01614.x/ (accessed on 18 September 2013). [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Jacklyn R. Barber. “Nursing Students’ Perception of Spiritual Awareness after Participating in a Spiritual Project.” Ed.D. Thesis, College of Saint Mary, Omaha, NE, USA, January 2008. [Google Scholar]

- Anne Vitale. “Nurses lived experiences of Reki for self-care.” Ph.D. Thesis, Nursing, College of nursing, Villanova University, Villanova, PA, USA, December 2008. [Google Scholar]

- Barbara Dossey. “Florence Nightingale and Holistic Nursing.” Journal of Holistic Nursing 52 (2005): 56–58. Available online: http://www.nsna.org/imprint_febmar 05 (accessed on 21 October 2013). [Google Scholar]

- Denise A. Du Toit, and S. Johann Van Staden. Nursing Sociology, 4th ed. Pretoria: Van Schaik Publishers, 2008. [Google Scholar]

- Mary Elizabeth O’brien. Spirituality in Nursing: Standing on Holy Ground, 4th ed. Burlington: Jones & Bartlett Learning, 2011. [Google Scholar]

- Mary Elizabeth O’brien. “Spirituality and Nursing.” Ezine Articles Nursing, 2009. Available online: http://EzineArticles.com/ (accessed on 10 September 2013). [Google Scholar]

- Lydia V. Monareng. “Spiritual nursing care: A concept analysis.” Curationis 35 (2012): 1–9. Available online: http://dx.doi.org/10.4102/curationis.v35i1.28 (accessed on 12 September 2013). [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Michael R. Levenson, Patricia A. Jennings, Carolyn M. Aldwin, and Ray W. Shiraishi. “Self-transcendence: conceptualization and measurement.” Internal Journal of Aging and Human Development 6 (2005): 127–43. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dee Marie Zyblock. “Nursing presence in contemporary nursing practice.” Nursing Forum 45 (2010): 120–24. Available online: http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/m/pubmed/20536761/ (accessed on 18 October 2013). [Google Scholar]

- Denise F. Polit, and Cheryl Tatano Beck. Nursing Research Generating and Assessing Evidence for Nursing Practice, 8th ed. Philadelphia: Lippincott Williams and Wilkins, 2008. [Google Scholar]

- Nancy Burns, and Susan K. Grove. The Practice of Nursing Research: Appraisals, Synthesis and Generation of Evidence, 6th ed. Maryland Heights: Saunders Elsevier, 2008. [Google Scholar]

- McSherry Wilfred. “Nurse’s perception of spirituality.” Nursing Standards 13 (1998): 36–49. Available online: http://www.proquest.umi.com (accessed on 10 September 2013). [Google Scholar]

- McSherry Wilfred. “The principal component model: a model for advancing spirituality and spiritual care practice.” Journal of Clinical Nursing 15 (2006): 905–17. Available online: http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/m/pubmed/16879383/ (accessed on 18 September 2013). [Google Scholar]

- Bhagwan Raisuyah. “The Role of Religion and Spirituality in Social Work Practice: Guidelines for Curricula Development at South African Schools of Social Work.” Ph.D. Thesis, University of Natal, Durban, South Africa, January 2002. [Google Scholar]

- Kathleen Lovanio, and Meredith Wallace. “Promoting spiritual knowledge and attitudes: A student nurse education project.” Holistic Nursing Practice 2 (2007): 42–47. Available online: http://oaks.journals.mobile/articleviewer.aspx?year=2007&issue=0100&article=00008 (accessed on 18 October 2013). [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lay H. Tiew, Vicki Drury, and Debra Creedy. “Singapore nursing student’s perception about spirituality and spiritual care: A qualitative study.” BMJ Palliative Support Journal 1 (2011): 84. Available online: http://espace.library.curtin.edu.au:80/ (accessed on 18 September 2013). [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Robert D. Mason, Douglas A. Lind, and William G. Marchal. Statistical Techniques in Business and Economics, 11th ed. New York: McGraw Hill, 2004. [Google Scholar]

- Hilla Brink, Christa van der Walt, and Gisela van Rensburg. Fundamentals of Research Methodology for Healthcare Professionals, 3rd ed. Cape Town: Juta and Co.Ltd, 2012. [Google Scholar]

- Maria E. Bailey, Sue Moran, and Margaret M. Graham. “Creating a spiritual tapestry of nurses’ experiences of delivering spiritual care to patients in an Irish hospice.” International Journal of Palliative Nursing 15 (2009): 42–48. Available online: http://dutlib.dut.ac.za:2062/ehost/ (accessed on 12 September 2013). [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Rebecca Carron, and Sharon Ann Cumbie. “Development of a conceptual nursing model for the implementation of spiritual care in adult primary health care.” Journal of American Academy of Nursing Practioners 23 (2011): 552–60. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- South African Nursing Council. “SANC Geographical Distribution.” Pretoria. 2012. Available online: http://www.sanc.org.za/stats/stat2012/ (accessed on 12 April 2012).

© 2016 by the authors; licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons by Attribution (CC-BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Chandramohan, S.; Bhagwan, R. Utilization of Spirituality and Spiritual Care in Nursing Practice in Public Hospitals in KwaZulu-Natal, South Africa. Religions 2016, 7, 23. https://doi.org/10.3390/rel7030023

Chandramohan S, Bhagwan R. Utilization of Spirituality and Spiritual Care in Nursing Practice in Public Hospitals in KwaZulu-Natal, South Africa. Religions. 2016; 7(3):23. https://doi.org/10.3390/rel7030023

Chicago/Turabian StyleChandramohan, Sandhya, and Raisuyah Bhagwan. 2016. "Utilization of Spirituality and Spiritual Care in Nursing Practice in Public Hospitals in KwaZulu-Natal, South Africa" Religions 7, no. 3: 23. https://doi.org/10.3390/rel7030023