ZnO Nanostructures for Drug Delivery and Theranostic Applications

Abstract

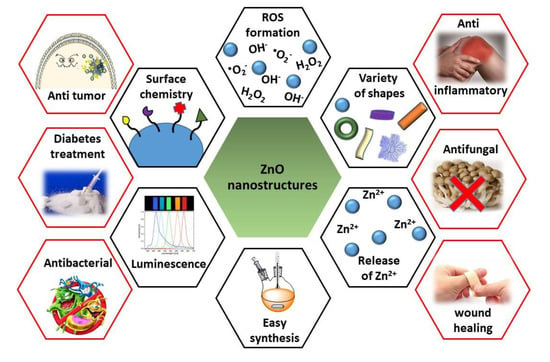

:1. Introduction

2. ZnO Nanoplatforms for Theranostic in Cancer

2.1. ZnO Core Nanosystems

2.2. ZnO Core Nanocomposites

2.3. ZnO Coated Nanodevices

2.4. ZnO QDs as Pore Caps

2.5. ZnO QDs That Provides an Added Value to Other Systems

3. ZnO Nanoplatforms for Bacterial Infection

3.1. ZnO Nanoplatforms for Planktonic Bacteria Treatment

3.2. ZnO Nanoplatforms for Biofilm Treatment

3.3. ZnO Nanoplatforms for Planktonic and Biofilm Treatment

4. Antifungal Capacity of ZnO Nanoplatforms

5. ZnO Nanoplatforms for Diabetes Treatment

6. ZnO Nanoplatforms with Anti-Inflammatory Properties

7. ZnO Nanoplatforms for Wound Healing

8. Conclusions and Future Outlook

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Jia, Z.; Misra, R.D.K. Tunable ZnO quantum dots for bioimaging: synthesis and photoluminescence. Mater. Technol. 2013, 28, 221–227. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Resch-Genger, U.; Grabolle, M.; Cavaliere-Jaricot, S.; Nitschke, R.; Nann, T. Quantum dots versus organic dyes as fluorescent labels. Nat. Methods 2008, 5, 763–775. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Volokitin, Y.; Sinzig, J.; de Jongh, L.J.; Schmid, G.; Vargaftik, M.N.; Moiseevi, I.I. Quantum-size effects in the thermodynamic properties of metallic nanoparticles. Nature 1996, 384, 621–623. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Asok, A.; Gandhi, M.N.; Kulkarni, A.R. Enhanced visible photoluminescence in ZnO quantum dots by promotion of oxygen vacancy formation. Nanoscale 2012, 4, 4943. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zhang, Z.-Y.; Xiong, H.-M. Photoluminescent ZnO Nanoparticles and Their Biological Applications. Materials 2015, 8, 3101–3127. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vandebriel, R.J.; De Jong, W.H. A review of mammalian toxicity of ZnO nanoparticles. Nanotechnol. Sci. Appl. 2012, 5, 61–71. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Espitia, P.J.P.; Soares, N.F.F.; Coimbra, J.S.; dos de Andrade, R.; Cruz, R.S.; Medeiros, E.A.A. Zinc Oxide Nanoparticles: Synthesis, Antimicrobial Activity and Food Packaging Applications. Food Bioprocess Technol. 2012, 5, 1447–1464. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, L.; Yin, L.; Wang, C.; Qi, Y.; Xiang, D. Origin of Visible Photoluminescence of ZnO Quantum Dots: Defect-Dependent and Size-Dependent. J. Phys. Chem. C 2010, 114, 9651–9658. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xiong, H.-M.; Shchukin, D.G.; Möhwald, H.; Xu, Y.; Xia, Y.-Y. Sonochemical Synthesis of Highly Luminescent Zinc Oxide Nanoparticles Doped with Magnesium(II). Angew. Chem. Int. Ed. 2009, 48, 2727–2731. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Manaia, E.B.; Kaminski, R.C.K.; Caetano, B.L.; Briois, V.; Chiavacci, L.A.; Bourgaux, C. Surface modified Mg-doped ZnO QDs for biological imaging. Eur. J. Nanomed. 2015, 7, 109–120. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fan, Z.; Lu, J.G. Zinc Oxide Nanostructures: Synthesis and Properties. J. Nanosci. Nanotechnol. 2005, 5, 1561–1573. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zhang, H.; Chen, B.; Jiang, H.; Wang, C.; Wang, H.; Wang, X. A strategy for ZnO nanorod mediated multi-mode cancer treatment. Biomaterials 2011, 32, 1906–1914. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Driscoll, K.E.; Howard, B.W.; Carter, J.M.; Janssen, Y.M.W.; Mossman, B.T.; Isfort, R.J. Mitochondrial-Derived Oxidants and Quartz Activation of Chemokine Gene Expression BT—Biological Reactive Intermediates VI: Chemical and Biological Mechanisms in Susceptibility to and Prevention of Environmental Diseases; Dansette, P.M., Snyder, R., Delaforge, M., Gibson, G.G., Greim, H., Jollow, D.J., Monks, T.J., Sipes, I.G., Eds.; Springer US: Boston, MA, USA, 2001; pp. 489–496. ISBN 978-1-4615-0667-6. [Google Scholar]

- Wilson, M.R.; Lightbody, J.H.; Donaldson, K.; Sales, J.; Stone, V. Interactions between ultrafine particles and transition metals in vivo and in vitro. Toxicol. Appl. Pharmacol. 2002, 184, 172–179. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Rasmussen, J.W.; Martinez, E.; Louka, P.; Wingett, D.G. Zinc Oxide Nanoparticles for Selective Destruction of Tumor Cells and Potential for Drug Delivery Applications. NIH Public Accsess 2011, 7, 1063–1077. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kim, Y.J.; Yu, M.; Park, H.O.; Yang, S.I. Comparative study of cytotoxicity, oxidative stress and genotoxicity induced by silica nanomaterials in human neuronal cell line. Mol. Cell. Toxicol. 2010, 6, 337–344. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ostrovsky, S.; Kazimirsky, G.; Gedanken, A.; Brodie, C. Selective cytotoxic effect of ZnO nanoparticles on glioma cells. Nano Res. 2009, 2, 882–890. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liou, M.-Y.; Storz, P. Reactive Oxygen Species in Cancer; Taylor & Francis: Oxfordshire, UK, 2010; Volume 44, ISBN 1071576100. [Google Scholar]

- Lepot, N.; Van Bael, M.K.; Van den Rul, H.; D’Haen, J.; Peeters, R.; Franco, D.; Mullens, J. Synthesis of ZnO nanorods from aqueous solution. Mater. Lett. 2007, 61, 2624–2627. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xi, Y.; Hu, C.G.; Han, X.Y.; Xiong, Y.F.; Gao, P.X.; Liu, G.B. Hydrothermal synthesis of ZnO nanobelts and gas sensitivity property. Solid State Commun. 2007, 141, 506–509. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tripathi, R.M.; Bhadwal, A.S.; Gupta, R.K.; Singh, P.; Shrivastav, A.; Shrivastav, B.R. ZnO nanoflowers: Novel biogenic synthesis and enhanced photocatalytic activity. J. Photochem. Photobiol. B Biol. 2014, 141, 288–295. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Samadipakchin, P.; Mortaheb, H.R.; Zolfaghari, A. ZnO nanotubes: Preparation and photocatalytic performance evaluation. J. Photochem. Photobiol. A Chem. 2017, 337, 91–99. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, W.C.; Cai, W. Synthesis and characterization of ZnO nanorings with ZnO nanowires array aligned at the inner surface without catalyst. J. Cryst. Growth 2008, 310, 843–846. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cho, E.B.; Volkov, D.O.; Sokolov, I. Ultrabright fluorescent mesoporous silica nanoparticles. Small 2010, 6, 2314–2319. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zhang, X.; Zhao, Y.; Cao, L.; Sun, L. Fabrication of degradable lemon-like porous silica nanospheres for pH/redox-responsive drug release. Sens. Actuators B Chem. 2018, 257, 105–115. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zamani, M.; Rostami, M.; Aghajanzadeh, M.; Kheiri Manjili, H.; Rostamizadeh, K.; Danafar, H. Mesoporous titanium dioxide@ zinc oxide–graphene oxide nanocarriers for colon-specific drug delivery. J. Mater. Sci. 2018, 53, 1634–1645. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kawabata, Y.; Wada, K.; Nakatani, M.; Yamada, S.; Onoue, S. Formulation design for poorly water-soluble drugs based on biopharmaceutics classification system: Basic approaches and practical applications. Int. J. Pharm. 2011, 420, 1–10. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hu, J.; Johnston, K.P.; Williams, R.O. Nanoparticle Engineering Processes for Enhancing the Dissolution Rates of Poorly Water Soluble Drugs. Drug Dev. Ind. Pharm. 2004, 30, 233–245. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Martínez-Carmona, M.; Lozano, D.; Colilla, M.; Vallet-Regí, M. Selective topotecan delivery to cancer cells by targeted pH-sensitive mesoporous silica nanoparticles. RSC Adv. 2016, 6, 50923–50932. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Manuscript, A.; Barriers, G.M. Oral Drug Delivery with Polymeric Nanoparticles: The Gastrointestinal Mucus Barriers. NIH Public Access 2013, 64, 557–570. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bahrami, B.; Hojjat-Farsangi, M.; Mohammadi, H.; Anvari, E.; Ghalamfarsa, G.; Yousefi, M.; Jadidi-Niaragh, F. Nanoparticles and targeted drug delivery in cancer therapy. Immunol. Lett. 2017, 190, 64–83. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kou, L.; Bhutia, Y.D.; Yao, Q.; He, Z.; Sun, J.; Ganapathy, V. Transporter-Guided Delivery of Nanoparticles to Improve Drug Permeation across Cellular Barriers and Drug Exposure to Selective Cell Types. Front. Pharmacol. 2018, 9, 27. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ghaemi, B.; Mashinchian, O.; Mousavi, T.; Karimi, R.; Kharrazi, S.; Amani, A. Harnessing the Cancer Radiation Therapy by Lanthanide-Doped Zinc Oxide Based Theranostic Nanoparticles. ACS Appl. Mater. Interfaces 2016, 8, 3123–3134. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ye, D.X.; Ma, Y.Y.; Zhao, W.; Cao, H.M.; Kong, J.L.; Xiong, H.M.; Möhwald, H. ZnO-Based Nanoplatforms for Labeling and Treatment of Mouse Tumors without Detectable Toxic Side Effects. ACS Nano 2016, 10, 4294–4300. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Król, A.; Pomastowski, P.; Rafińska, K.; Railean-Plugaru, V.; Buszewski, B. Zinc oxide nanoparticles: Synthesis, antiseptic activity and toxicity mechanism. Adv. Colloid Interface Sci. 2017, 249, 37–52. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Mirzaei, H.; Darroudi, M. Zinc oxide nanoparticles: Biological synthesis and biomedical applications. Ceram. Int. 2017, 43, 907–914. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Singh, A.; Singh, N.B.; Afzal, S.; Singh, T.; Hussain, I. Zinc oxide nanoparticles: a review of their biological synthesis, antimicrobial activity, uptake, translocation and biotransformation in plants. J. Mater. Sci. 2018, 53, 185–201. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Naveed Ul Haq, A.; Nadhman, A.; Ullah, I.; Mustafa, G.; Yasinzai, M.; Khan, I. Synthesis Approaches of Zinc Oxide Nanoparticles: The Dilemma of Ecotoxicity. J. Nanomater. 2017, 2017, 1–14. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ludi, B.; Niederberger, M. Zinc oxide nanoparticles: chemical mechanisms and classical and non-classical crystallization. Dalt. Trans. 2013, 42, 12554–12568. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- David, C.A.; Galceran, J.; Rey-Castro, C.; Puy, J.; Companys, E.; Salvador, J.; Monné, J.; Wallace, R.; Vakourov, A. Dissolution kinetics and solubility of ZnO nanoparticles followed by AGNES. J. Phys. Chem. C 2012, 116, 11758–11767. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bisht, G.; Rayamajhi, S. ZnO Nanoparticles: A Promising Anticancer Agent. Nanobiomedicine 2016, 3, 9. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sharma, H.; Kumar, K.; Choudhary, C.; Mishra, P.K.; Vaidya, B. Development and characterization of metal oxide nanoparticles for the delivery of anticancer drug. Artif. Cells Nanomed. Biotechnol. 2016, 44, 672–679. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Liu, J.; Ma, X.; Jin, S.; Xue, X.; Zhang, C.; Wei, T.; Guo, W.; Liang, X.J. Zinc Oxide Nanoparticles as Adjuvant to Facilitate Doxorubicin Intracellular Accumulation and Visualize pH-Responsive Release for Overcoming Drug Resistance. Mol. Pharm. 2016, 13, 1723–1730. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wang, J.; Lee, J.S.; Kim, D.; Zhu, L. Exploration of Zinc Oxide Nanoparticles as a Multitarget and Multifunctional Anticancer Nanomedicine. ACS Appl. Mater. Interfaces 2017, 9, 39971–39984. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Barick, K.C.; Nigam, S.; Bahadur, D. Nanoscale assembly of mesoporous ZnO: A potential drug carrier. J. Mater. Chem. 2010, 20, 6446. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Muhammad, F.; Guo, M.; Guo, Y.; Qi, W.; Qu, F.; Sun, F.; Zhao, H.; Zhu, G. Acid degradable ZnO quantum dots as a platform for targeted delivery of an anticancer drug. J. Mater. Chem. 2011, 21, 13406. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Puvvada, N.; Rajput, S.; Prashanth Kumar, B.; Sarkar, S.; Konar, S.; Brunt, K.R.; Rao, R.R.; Mazumdar, A.; Das, S.K.; Basu, R.; Fisher, P.B.; Mandal, M.; Pathak, A. Novel ZnO hollow-nanocarriers containing paclitaxel targeting folate-receptors in a malignant pH-microenvironment for effective monitoring and promoting breast tumor regression. Sci. Rep. 2015, 5, 1–15. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Vimala, K.; Shanthi, K.; Sundarraj, S.; Kannan, S. Synergistic effect of chemo-photothermal for breast cancer therapy using folic acid (FA) modified zinc oxide nanosheet. J. Colloid Interface Sci. 2017, 488, 92–108. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Deng, Y.; Zhang, H. The synergistic effect and mechanism of doxorubicin-ZnO nanocomplexes as a multimodal agent integrating diverse anticancer therapeutics. Int. J. Nanomed. 2013, 8, 1835–1841. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hackenberg, S.; Scherzed, A.; Harnisch, W.; Froelich, K.; Ginzkey, C.; Koehler, C.; Hagen, R.; Kleinsasser, N. Antitumor activity of photo-stimulated zinc oxide nanoparticles combined with paclitaxel or cisplatin in HNSCC cell lines. J. Photochem. Photobiol. B Biol. 2012, 114, 87–93. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Han, Z.; Wang, X.; Heng, C.; Han, Q.; Cai, S.; Li, J.; Qi, C.; Liang, W.; Yang, R.; Wang, C. Synergistically enhanced photocatalytic and chemotherapeutic effects of aptamer-functionalized ZnO nanoparticles towards cancer cells. Phys. Chem. Chem. Phys. 2015, 17, 21576–21582. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Yan, Z.; Zhao, A.; Liu, X.; Ren, J.; Qu, X. A pH-switched mesoporous nanoreactor for synergetic therapy. Nano Res. 2017, 10, 1651–1661. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dumontel, B.; Canta, M.; Engelke, H.; Chiodoni, A.; Racca, L.; Ancona, A.; Limongi, T.; Canavese, G.; Cauda, V. Enhanced biostability and cellular uptake of zinc oxide nanocrystals shielded with a phospholipid bilayer. J. Mater. Chem. B 2017, 5, 8799–8813. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Qiu, H.; Cui, B.; Zhao, W.; Chen, P.; Peng, H.; Wang, Y. A novel microwave stimulus remote controlled anticancer drug release system based on Fe3 O4 @ZnO@mGd2 O3:Eu@P(NIPAm-co-MAA) multifunctional nanocarriers. J. Mater. Chem. B 2015, 3, 6919–6927. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Peng, H.; Cui, B.; Li, G.; Wang, Y.; Li, N.; Chang, Z.; Wang, Y. A multifunctional β-CD-modified Fe3O4ZnO:Er3 +,Yb3 +nanocarrier for antitumor drug delivery and microwave-triggered drug release. Mater. Sci. Eng. C 2015, 46, 253–263. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Muhammad, F.; Guo, M.; Qi, W.; Sun, F.; Wang, A.; Guo, Y.; Zhu, G. PH-triggered controlled drug release from mesoporous silica nanoparticles via intracelluar dissolution of ZnO nanolids. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2011, 133, 8778–8781. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Muhammad, F.; Wang, A.; Guo, M.; Zhao, J.; Qi, W.; Yingjie, G.; Gu, J.; Zhu, G. PH dictates the release of hydrophobic drug cocktail from mesoporous nanoarchitecture. ACS Appl. Mater. Interfaces 2013, 5, 11828–11835. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wang, Y.; Song, S.; Liu, J.; Liu, D.; Zhang, H. ZnO-functionalized upconverting nanotheranostic agent: Multi-modality imaging-guided chemotherapy with on-demand drug release triggered by pH. Angew. Chem. Int. Ed. 2015, 54, 536–540. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Qiu, L.; Zhao, Y.; Li, B.; Wang, Z.; Cao, L.; Sun, L. Triple-stimuli (protease/redox/pH) sensitive porous silica nanocarriers for drug delivery. Sens. Actuators B Chem. 2017, 240, 1066–1074. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Huang, X.; Wu, S.; Du, X. Gated mesoporous carbon nanoparticles as drug delivery system for stimuli-responsive controlled release. Carbon N. Y. 2016, 101, 135–142. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, J.; Chen, L.; Chen, J.; Wu, D.; Feng, J. Dextran microgels loaded with ZnO QDs: pH-triggered degradation under acidic conditions. J. Appl. Polym. Sci. 2018, 135, 1–6. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, G.-Y.; Pang, D.W.-P.; Hwang, S.-M.; Tuan, H.-Y.; Hu, Y.-C. A graphene-based platform for induced pluripotent stem cells culture and differentiation. Biomaterials 2012, 33, 418–427. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Chen, G.-Y.; Chen, C.-L.; Tuan, H.-Y.; Yuan, P.-X.; Li, K.-C.; Yang, H.-J.; Hu, Y.-C. Graphene Oxide Triggers Toll-Like Receptors/Autophagy Responses In Vitro and Inhibits Tumor Growth In Vivo. Adv. Healthc. Mater. 2014, 3, 1486–1495. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hanley, C.; Layne, J.; Punnoose, A.; Reddy, K.M.; Coombs, I.; Coombs, A.; Feris, K.; Wingett, D. Preferential killing of cancer cells and activated human T cells using ZnO nanoparticles. Nanotechnology 2008, 19, 295103. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wang, H.; Wingett, D.; Engelhard, M.H.; Feris, K.; Reddy, K.M.; Turner, P.; Layne, J.; Hanley, C.; Bell, J.; Tenne, D.; Wang, C.; Punnoose, A. Fluorescent dye encapsulated ZnO particles with cell-specific toxicity for potential use in biomedical applications. J. Mater. Sci. Mater. Med. 2009, 20, 11–22. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Colilla, M.; González, B.; Vallet-Regí, M. Mesoporous silicananoparticles for the design of smart delivery nanodevices. Biomater. Sci. 2013, 1, 114–134. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Baeza, A.; Colilla, M.; Vallet-Regí, M. Advances in mesoporous silica nanoparticles for targeted stimuli-responsive drug delivery. Expert Opin. Drug Deliv. 2015, 12, 319–337. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Martínez-Carmona, M.; Colilla, M.; Vallet-Regí, M. Smart Mesoporous Nanomaterials for Antitumor Therapy. Nanomaterials 2015, 5, 1906–1937. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Van Oosten, M.; Schäfer, T.; Gazendam, J.A.C.; Ohlsen, K.; Tsompanidou, E.; De Goffau, M.C.; Harmsen, H.J.M.; Crane, L.M.A.; Lim, E.; Francis, K.P.; et al. Real-time in vivo imaging of invasive- and biomaterial-associated bacterial infections using fluorescently labelled vancomycin. Nat. Commun. 2013, 4. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Israel, O.; Keidar, Z. PET/CT imaging in infectious conditions. Ann. N. Y. Acad. Sci. 2011, 1228, 150–166. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sievert, D.M.; Ricks, P.; Edwards, J.R.; Schneider, A.; Patel, J.; Srinivasan, A.; Kallen, A.; Limbago, B.; Fridkin, S. Antimicrobial-Resistant Pathogens Associated with Healthcare-Associated Infections: Summary of Data Reported to the National Healthcare Safety Network at the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention, 2009–2010. Infect. Control Hosp. Epidemiol. 2013, 34, 1–14. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Høiby, N.; Bjarnsholt, T.; Givskov, M.; Molin, S.; Ciofu, O. Antibiotic resistance of bacterial biofilms. Int. J. Antimicrob. Agents 2018, 35, 322–332. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Pinto-Alphandary, H.; Andremont, A.; Couvreur, P. Targeted delivery of antibiotics using liposomes and nanoparticles: Research and applications. Int. J. Antimicrob. Agents 2000, 13, 155–168. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dinjaski, N.; Suri, S.; Valle, J.; Lehman, S.M.; Lasa, I.; Prieto, M.A.; García, A.J. Near-infrared fluorescence imaging as an alternative to bioluminescent bacteria to monitor biomaterial-associated infections. Acta Biomater. 2014, 10, 2935–2944. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Manzoor, U.; Siddique, S.; Ahmed, R.; Noreen, Z.; Bokhari, H.; Ahmad, I. Antibacterial, structural and optical characterization of mechano-chemically prepared ZnO nanoparticles. PLoS ONE 2016, 11, 1–12. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Reddy, K.M.; Feris, K.; Bell, J.; Wingett, D.G.; Hanley, C.; Punnoose, A. Selective toxicity of zinc oxide nanoparticles to prokaryotic and eukaryotic systems. Appl. Phys. Lett. 2007, 90, 213902–213903. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wang, L.; Hu, C.; Shao, L. The antimicrobial activity of nanoparticles: Present situation and prospects for the future. Int. J. Nanomed. 2017, 12, 1227–1249. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Applerot, G.; Lipovsky, A.; Dror, R.; Perkas, N.; Nitzan, Y.; Lubart, R.; Gedanken, A. Enhanced Antibacterial Activity of Nanocrystalline ZnO Due to Increased ROS-Mediated Cell Injury. Adv. Funct. Mater. 2009, 19, 842–852. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Raghupathi, K.R.; Koodali, R.T.; Manna, A.C. Size-dependent bacterial growth inhibition and mechanism of antibacterial activity of zinc oxide nanoparticles. Langmuir 2011, 27, 4020–4028. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Xie, Y.; He, Y.; Irwin, P.L.; Jin, T.; Shi, X. Antibacterial activity and mechanism of action of zinc oxide nanoparticles against Campylobacter jejuni. Appl. Environ. Microbiol. 2011, 77, 2325–2331. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Jafari, A.R.; Mosavi, T.; Mosavari, N.; Majid, A.; Movahedzade, F.; Tebyaniyan, M.; Kamalzadeh, M.; Dehgan, M.; Jafari, S.; Arastoo, S. Mixed metal oxide nanoparticles inhibit growth of Mycobacterium tuberculosis into THP-1 cells. Int. J. Mycobacteriol. 2016, 5, S181–S183. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Gupta, J.; Bahadur, D. Visible Light Sensitive Mesoporous Cu-Substituted ZnO Nanoassembly for Enhanced Photocatalysis, Bacterial Inhibition, and Noninvasive Tumor Regression. ACS Sustain. Chem. Eng. 2017, 5, 8702–8709. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kadiyala, U.; Tulari-Emre, E.S.; Bahng, J.H.; Kotov, N.A.; VanEpps, J.S. Unexpected insights into antibacterial activity of zinc oxide nanoparticles against methicillin resistant Staphylococcus aureus (MRSA). Nanoscale 2018, 4927–4939. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sehmi, S.K.; Noimark, S.; Bear, J.C.; Peveler, W.J.; Bovis, M.; Allan, E.; MacRobert, A.J.; Parkin, I.P. Lethal photosensitisation of Staphylococcus aureus and Escherichia coli using crystal violet and zinc oxide-encapsulated polyurethane. J. Mater. Chem. B 2015, 3, 6490–6500. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, H.; Zhang, M.; Li, B.; Chen, D.; Dong, X.; Wang, Y.; Gu, Y. Versatile antimicrobial peptide-based ZnO quantum dots for invivo bacteria diagnosis and treatment with high specificity. Biomaterials 2015, 53, 532–544. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Aponiene, K.; Serevičius, T.; Luksiene, Z.; Juršėnas, S. Inactivation of bacterial biofilms using visible-light-activated unmodified ZnO nanorods. Nanotechnology 2017, 28, 365701. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Dwivedi, S.; Wahab, R.; Khan, F.; Mishra, Y.K.; Musarrat, J.; Al-Khedhairy, A.A. Reactive oxygen species mediated bacterial biofilm inhibition via zinc oxide nanoparticles and their statistical determination. PLoS ONE 2014, 9, 1–9. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lee, J.H.; Kim, Y.G.; Cho, M.H.; Lee, J. ZnO nanoparticles inhibit Pseudomonas aeruginosa biofilm formation and virulence factor production. Microbiol. Res. 2014, 169, 888–896. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Shakerimoghaddam, A.; Ghaemi, E.A.; Jamalli, A. Zinc oxide nanoparticle reduced biofilm formation and antigen 43 expressions in uropathogenic Escherichia coli. Iran. J. Basic Med. Sci. 2017, 20, 451–456. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sarwar, S.; Chakraborti, S.; Bera, S.; Sheikh, I.A.; Hoque, K.M.; Chakrabarti, P. The antimicrobial activity of ZnO nanoparticles against Vibrio cholerae: Variation in response depends on biotype. Nanomed. Nanotechnol. Biol. Med. 2016, 12, 1499–1509. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Schey, K.L.; Luther, J.M.; Rose, K.L. Zinc Oxide Nanoparticle Suspensions and Layer-By-Layer Coatings Inhibit Staphylococcal Growth. Nanomedicine 2016, 12, 1–21. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Alves, M.M.; Bouchami, O.; Tavares, A.; Córdoba, L.; Santos, C.F.; Miragaia, M.; De Fátima Montemor, M. New Insights into Antibiofilm Effect of a Nanosized ZnO Coating against the Pathogenic Methicillin Resistant Staphylococcus aureus. ACS Appl. Mater. Interfaces 2017, 9, 28157–28167. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Liao, H.; Miao, X.; Ye, J.; Wu, T.; Deng, Z.; Li, C.; Jia, J.; Cheng, X.; Wang, X. Falling Leaves Inspired ZnO Nanorods-Nanoslices Hierarchical Structure for Implant Surface Modification with Two Stage Releasing Features. ACS Appl. Mater. Interfaces 2017, 9, 13009–13015. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hsueh, Y.H.; Ke, W.J.; Hsieh, C. Te; Lin, K.S.; Tzou, D.Y.; Chiang, C.L. ZnO nanoparticles affect bacillus subtilis cell growth and biofilm formation. PLoS ONE 2015, 10, 1–23. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ghasemi, F.; Jalal, R. Antimicrobial action of zinc oxide nanoparticles in combination with ciprofloxacin and ceftazidime against multidrug-resistant Acinetobacter baumannii. J. Glob. Antimicrob. Resist. 2016, 6, 118–122. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Spadaro, D.; Garibaldi, A.; Gullino, M.L. Control of Penicillium expansum and Botrytis cinerea on apple combining a biocontrol agent with hot water dipping and acibenzolar-S-methyl, baking soda, or ethanol application. Postharv. Biol. Technol. 2004, 33, 141–151. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- He, L.; Liu, Y.; Mustapha, A.; Lin, M. Antifungal activity of zinc oxide nanoparticles against Botrytis cinerea and Penicillium expansum. Microbiol. Res. 2011, 166, 207–215. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Surendra, T.V.; Roopan, S.M.; Al-Dhabi, N.A.; Arasu, M.V.; Sarkar, G.; Suthindhiran, K. Vegetable Peel Waste for the Production of ZnO Nanoparticles and its Toxicological Efficiency, Antifungal, Hemolytic, and Antibacterial Activities. Nanoscale Res. Lett. 2016, 11. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Gunalan, S.; Sivaraj, R.; Rajendran, V. Green synthesized ZnO nanoparticles against bacterial and fungal pathogens. Prog. Nat. Sci. Mater. Int. 2012, 22, 693–700. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Arciniegas-Grijalba, P.A.; Patiño-Portela, M.C.; Mosquera-Sánchez, L.P.; Guerrero-Vargas, J.A.; Rodríguez-Páez, J.E. ZnO nanoparticles (ZnO-NPs) and their antifungal activity against coffee fungus Erythricium salmonicolor. Appl. Nanosci. 2017, 7, 225–241. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sierra-Fernandez, A.; De La Rosa-García, S.C.; Gomez-Villalba, L.S.; Gómez-Cornelio, S.; Rabanal, M.E.; Fort, R.; Quintana, P. Synthesis, Photocatalytic, and Antifungal Properties of MgO, ZnO and Zn/Mg Oxide Nanoparticles for the Protection of Calcareous Stone Heritage. ACS Appl. Mater. Interfaces 2017, 9, 24873–24886. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Jasim, N.O. Antifungal Activity of Zinc Oxide Nanoparticles on Aspergillus Fumigatus Fungus & Candida Albicans Yeast. Citeseer 2015, 5, 23–28. [Google Scholar]

- Hong, R.Y.; Li, J.H.; Chen, L.L.; Liu, D.Q.; Li, H.Z.; Zheng, Y.; Ding, J. Synthesis, surface modification and photocatalytic property of ZnO nanoparticles. Powder Technol. 2009, 189, 426–432. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Palmquist, D.L.; Lock, A.L.; Shingfield, K.J.; Bauman, D.E. Biosynthesis of Conjugated Linoleic Acid in Ruminants and Humans. In Advances in Food and Nutrition Research; Academic Press: Cambridge, MA, USA, 2005; Volume 50, pp. 179–217. [Google Scholar]

- Barad, S.; Roudbary, M.; Omran, N.A.; Daryasari, P.M. Preparation and characterization of ZnO nanoparticles coated by chitosan-linoleic acid; fungal growth and biofilm assay. Bratisl. Med. J.-Bratisl. Lek. List. 2017, 118, 169–174. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Decelis, S.; Sardella, D.; Triganza, T.; Brincat, J.-P.; Gatt, R.; Valdramidis, V.P. Assessing the anti-fungal efficiency of filters coated with zinc oxide nanoparticles. R. Soc. Open Sci. 2017, 4, 1–9. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Esteban-Tejeda, L.; Prado, C.; Cabal, B.; Sanz, J.; Torrecillas, R.; Moya, J.S. Antibacterial and antifungal activity of ZnO containing glasses. PLoS ONE 2015, 10. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- National Diabetes Statistics Report. 2017. Available online: https://www.cdc.gov/diabetes/data/statistics-report/index.html (accessed on 23 April 2018).

- Abel, J.J. Crystalline Insulin. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 1926, 12, 132–136. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ranasinghe, P.; Pigera, S.; Galappatthy, P.; Katulanda, P.; Constantine, G.R. Zinc and diabetes mellitus: Understanding molecular mechanisms and clinical implications. DARU J. Pharm. Sci. 2015, 23, 1–13. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Umrani, R.D.; Paknikar, K.M. Zinc oxide nanoparticles show antidiabetic activity in streptozotocin-induced Type 1 and 2 diabetic rats. Nanomedicine 2014, 9, 89–104. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Nazarizadeh, A.; Asri-Rezaie, S. Comparative Study of Antidiabetic Activity and Oxidative Stress Induced by Zinc Oxide Nanoparticles and Zinc Sulfate in Diabetic Rats. AAPS PharmSciTech 2016, 17, 834–843. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wahba, N.S.; Shaban, S.F.; Kattaia, A.A.A.; Kandeel, S.A. Efficacy of zinc oxide nanoparticles in attenuating pancreatic damage in a rat model of streptozotocin-induced diabetes. Ultrastruct. Pathol. 2016, 40, 358–373. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Shanker, K.; Naradala, J.; Mohan, G.K.; Kumar, G.S.; Pravallika, P.L. A sub-acute oral toxicity analysis and comparative in vivo anti-diabetic activity of zinc oxide, cerium oxide, silver nanoparticles, and Momordica charantia in streptozotocin-induced diabetic Wistar rats. RSC Adv. 2017, 7, 37158–37167. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- El-Gharbawy, R.M.; Emara, A.M.; Abu-Risha, S.E.S. Zinc oxide nanoparticles and a standard antidiabetic drug restore the function and structure of beta cells in Type-2 diabetes. Biomed. Pharmacother. 2016, 84, 810–820. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kitture, R.; Chordiya, K.; Gaware, S.; Ghosh, S.; More, P.A.; Kulkarni, P.; Chopade, B.A.; Kale, S.N. ZnO Nanoparticles-Red Sandalwood Conjugate: A Promising Anti-Diabetic Agent. J. Nanosci. Nanotechnol. 2015, 15, 4046–4051. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Gupta, M.; Mahajan, V.K.; Mehta, K.S.; Chauhan, P.S. Zinc therapy in dermatology: A review. Dermatol. Res. Pract. 2014, 2014. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ilves, M.; Palomaki, J.; Vippola, M.; Lehto, M.; Savolainen, K.; Savinko, T.; Alenius, H. Topically applied ZnO nanoparticles suppress allergen induced skin inflammation but induce vigorous IgE production in the atopic dermatitis mouse model. Part. Fibre Toxicol. 2014, 11, 1–12. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Nagajyothi, P.C.; Cha, S.J.; Yang, I.J.; Sreekanth, T.V.M.; Kim, K.J.; Shin, H.M. Antioxidant and anti-inflammatory activities of zinc oxide nanoparticles synthesized using Polygala tenuifolia root extract. J. Photochem. Photobiol. B Biol. 2015, 146, 10–17. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Li, J.; Chen, H.; Wang, B.; Cai, C.; Yang, X.; Chai, Z.; Feng, W. ZnO nanoparticles act as supportive therapy in DSS-induced ulcerative colitis in mice by maintaining gut homeostasis and activating Nrf2 signaling. Sci. Rep. 2017, 7, 1–11. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Singh, B.N.; Rawat, A.K.S.; Khan, W.; Naqvi, A.H.; Singh, B.R. Biosynthesis of stable antioxidant ZnO nanoparticles by Pseudomonas aeruginosa Rhamnolipids. PLoS ONE 2014, 9. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Agren, M.S. Studies on zinc in wound-healing. Acta Derm. Venereol. 1990, 1–36. [Google Scholar]

- Lansdown, A.B.G.; Mirastschijski, U.; Stubbs, N.; Scanlon, E.; Ågren, M.S. Zinc in wound healing: Theoretical, experimental, and clinical aspects. Wound Repair Regen. 2007, 15, 2–16. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kogan, S.; Sood, A.; Granick, M.S. Zinc and Wound Healing: A Review of Zinc Physiology and Clinical Applications. WOUNDS-A Compend. Clin. Res. Pract. 2017, 29, 102–106. [Google Scholar]

- Sudheesh Kumar, P.T.; Lakshmanan, V.K.; Anilkumar, T.V.; Ramya, C.; Reshmi, P.; Unnikrishnan, A.G.; Nair, S.V.; Jayakumar, R. Flexible and microporous chitosan hydrogel/nano ZnO composite bandages for wound dressing: In vitro and in vivo evaluation. ACS Appl. Mater. Interfaces 2012, 4, 2618–2629. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Raguvaran, R.; Manuja, B.K.; Chopra, M.; Thakur, R.; Anand, T.; Kalia, A.; Manuja, A. Sodium alginate and gum acacia hydrogels of ZnO nanoparticles show wound healing effect on fibroblast cells. Int. J. Biol. Macromol. 2017, 96, 185–191. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Croisier, F.; Jérôme, C. Chitosan-based biomaterials for tissue engineering. Eur. Polym. J. 2013, 49, 780–792. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Karahaliloglu, Z.; Kilicay, E.; Denkbas, E.B. Antibacterial chitosan/silk sericin 3D porous scaffolds as a wound dressing material. Artif. Cells Nanomed. Biotechnol. 2017, 45, 1172–1185. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Cahú, T.B.; Silva, R.A.; Silva, R.P.F.; Silva, M.M.; Arruda, I.R.S.; Silva, J.F.; Costa, R.M.P.B.; Santos, S.D.; Nader, H.B.; Bezerra, R.S. Evaluation of Chitosan-Based Films Containing Gelatin, Chondroitin 4-Sulfate and ZnO for Wound Healing. Appl. Biochem. Biotechnol. 2017, 183, 765–777. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

| Type of Cell/Animal Used a | Type of Device b | Responsive Phenomena c | Drug/Antibiotic d | Reference |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| MCF-7 | ZnO QDs | - | Adsorbed DOX | [42] |

| MCF-7R, MCF-7S | ZnO QDs | pH | Loaded DOX | [43] |

| MDA-MB-231, HeLa, NCI/ADR-RES, MES-SA/Dx5 | ZnO QDs | pH | Adsorbed DOX | [44] |

| - | ZnO QDs | pH, ultrasounds | Loaded DOX | [45] |

| HeLa | FA Mg ZnO QDs | pH | Adsorbed DOX | [46] |

| MCF-7, MDA-MB-231, nude mice | FA Hollow ZnO NPs | pH | Loaded paclitaxel | [47] |

| MDA-MB-231, HBL-100, mice | FA ZnO Nanosheets | pH, heat | Loaded DOX | [48] |

| SMMC-7721 | ZnO nanorod | UV radiation | - | [12] |

| HeLa, PC3 | Lanthanide–ZnO QDs | UV, X-ray, γ-ray radiation | - | [33] |

| SMMC-7721 | ZnO nanorod | UV radiation | DOX complex | [49] |

| HNSCC | ZnO QDs | UVA irradiation | Paclitaxel, cisplatin | [50] |

| MCF-7 | MUC1 aptamer S2.2. ZnO QDs | UV radiation | Loaded DOX | [51] |

| BxPC-3, tumour-bearing nude mice | Gd-Polymer–ZnO QDs | pH | Adsorbed DOX | [34] |

| HEK 293T, HeLa | FA-SiO2 ZnO NPs | pH | Loaded DOX | [52] |

| HeLa | Lipid ZnO NCs | pH | - | [53] |

| Caco-2 | TiO2@ZnO–GO and TiO2@ZnO | pH | Loaded Cur | [26] |

| - | Fe3O4@ZnO@mGd2O3:Eu@P(NIPAm-co-MAA) | Microwave, Magnetic radiation | VP-16 | [54] |

| MCF-7 | β-CD-Fe3O4@ZnO: Er3+, Yb3+ | Microwave, Magnetic radiation | VP-16 | [55] |

| HeLa | ZnO MSNs | pH | Loaded DOX | [56] |

| BxPC-3 | Mg ZnO MSNs | pH | Loaded CPT, adsorbed Cur | [57] |

| HeLa, mouse | UCNPs@mSiO2-ZnO | pH | Loaded DOX | [58] |

| - | ZnO-pSiO2-GSSG NPs | Protease, redox, pH | Loaded amoxicillin | [59] |

| HepG2 | l-pSiO2/Cys/ZnO NPs | Redox, pH | Loaded DOX | [25] |

| A549 | ZnO-MCNs | pH | Loaded MIT | [60] |

| HeLa | ZnO@-Dextran microgels | pH | Loaded DOX | [61] |

| Type of Bacteria Used a | Type of Device b | Responsive Phenomena c | Drug/Antibiotic d | Reference |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| C. jejuni | ZnO QDs | - | - | [80] |

| EPEC, C. jejuni, V. Cholerae, MRSA | ZnO QDs | - | - | [75] |

| THP-1, M. tuberculosis | ZnO QDs + Ag QDs | - | - | [81] |

| A. baumannii | ZnO QDs | - | Coadministered Cip, Cef | [95] |

| E. coli | Cu-ZnO NAs | Visible light | - | [82] |

| MRSA | ZnO-NPYs, ZnO QDs | - | - | [83] |

| S. aureus, E. coli | CVZnO polyurethane surface | White light | Loaded CV | [84] |

| S. aureus, B. subtilis, MRSA, S. aureusor B. subtilis infected mouse | MPA@ZnO-PEP | - | Loaded Met, Van | [85] |

| MSCL 302, ATCL3C 7644, O157:H7 | ZnO NRs | UV light | - | [86] |

| P. aeruginosa | ZnO QDs | - | - | [87] |

| P. aeruginosa | ZnO QDs | - | - | [88] |

| E. coli | ZnO QDs | - | - | [89] |

| V. cholerae, Mouse intestinal loop | ZnO QDs | - | Coadministered kanamycin | [90] |

| S. epidermidis, S. aureus, K. pneumonia, E. coli | ZnO (spheres, plates, pyramids) | - | - | [91] |

| MRSA | Nano- and micro-sized ZnO coatings | - | Coadministered, Gent, Trim, Rif, Cip, Van | [92] |

| S. aureus, E. coli, mice | NHS, ZnO NRs, ZnO NSs | - | - | [93] |

| Type of Fungi Used a | Type of Device b | Responsive Phenomena c | Reference |

|---|---|---|---|

| B. cinerea, P. expansum | ZnO QDs | - | [97] |

| A. saloni, S. rolfii | ZnO QDs | - | [98] |

| R. stolonifera, A. flavus, A. nidulans, T. harzianum | ZnO QDs | - | [99] |

| E. salmonicolor | ZnO QDs | - | [100] |

| A. niger, P. oxalicum, Paraconiothyrium sp., P. maculans | Zn/Mg Oxide QDs | UV light | [101] |

| A. fumigatus, C. albicans | ZnO QDs | - | [102] |

| C. albicans | CS-LiA ZnO QDs | - | [105] |

| R. stolonifera, P. expansum | ZnO QDs | - | [106] |

| C. krusei | ZnO QDs | - | [107] |

| Model Used | Type of Device a | Drug/Antibiotic b | Reference |

|---|---|---|---|

| Rats | ZnO QDs | - | [111] |

| Rats | ZnO QDs, ZnSO4 | - | [112] |

| Rats | ZnO QDs | - | [113] |

| Rats | ZnO, CeO2, Ag QDs, MC | - | [114] |

| Rats | ZnO QDs | Coadministered Vildagliptin | [115] |

| Murine Pancreatic and Small Intestinal Extracts | ZnO QDs | Conjugated RSW | [116] |

| Model Used a | Type of Device b | Reference |

|---|---|---|

| AD model mouse | nZnO, bZnO | [118] |

| RAW 264.7 | ZnO QDs | [119] |

| mice | ZnO QDs | [120] |

| Model Used a | Type of Device b | Reference |

|---|---|---|

| nHDF cells, SD rats | CZBs | [125] |

| PBMC, sheep fibroblast cells | SAGA-ZnO QDs hydrogels | [126] |

| HaCaT | CHT/SS/ZnO QDs, CHT/SS/LA | [128] |

| rats | CHT/gel/C4S/ZnO films | [129] |

© 2018 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Martínez-Carmona, M.; Gun’ko, Y.; Vallet-Regí, M. ZnO Nanostructures for Drug Delivery and Theranostic Applications. Nanomaterials 2018, 8, 268. https://doi.org/10.3390/nano8040268

Martínez-Carmona M, Gun’ko Y, Vallet-Regí M. ZnO Nanostructures for Drug Delivery and Theranostic Applications. Nanomaterials. 2018; 8(4):268. https://doi.org/10.3390/nano8040268

Chicago/Turabian StyleMartínez-Carmona, Marina, Yurii Gun’ko, and María Vallet-Regí. 2018. "ZnO Nanostructures for Drug Delivery and Theranostic Applications" Nanomaterials 8, no. 4: 268. https://doi.org/10.3390/nano8040268