Pseudo-Media Sites, Polarization, and Pandemic Skepticism in Spain

- Department of Language Theory and Communication Sciences, University of Valencia, Valencia, Spain

The Coronavirus pandemic has triggered an authentic infodemic, which is a global epidemic of disinformation that has spread throughout most of the world. Social media platforms and pseudo-media outlets have contributed to the problem by producing and disseminating misleading content that is potentially dangerous to public health. This research focuses on a rather unknown phenomenon, which involves digital sites that mimic the appearance of news media but provide pseudo-information. Five Spanish pseudo-media have been analyzed with the aim of enhancing understanding of the issues and the frames presented. The results show clear links with the far-right ideology as well as the presence of a populist, polarized discourse through the use of belligerent, offensive expressions to refer to institutions and their representatives. Politics is the main issue represented, with a frame that clearly points out the incompetence and cynicism of the Spanish government. Conspiracy theories associate the origins of the pandemic to a Chinese laboratory and emphasize a global plan to establish systemic control. Measures to stop the virus are framed as harmful and ineffective, linked to a euthanasia scheme targeted at older people, especially regarding vaccination, which is presented as a solution offered for economic interests.

Introduction

The pandemic has fomented a wave of conspiracy theories (Boberg et al., 2020), as well as skepticism (Brubaker, 2020) regarding preventive measures and the vaccination program against Covid-19. From the outset, authorities warned of the dangers of disinformation, including the General Director of the WHO, Tedros Adhanom Ghebreyesus, on February 15th, 2020, when he made the following statement: “We’re not just fighting an epidemic; we’re fighting an infodemic.” The term “infodemic” has been promptly adopted by scholars (Bechmann, 2020; Cinelli et al., 2020; Zarocostas, 2020) in order to explain how the current hybrid media context (Chadwick, 2017) has fostered the dissemination of conspiracy theories (Bruder and Kunert, 2020; Romer and Jamieson, 2020), as well as disinformation regarding the coronavirus (Nguyen and Catalan, 2020). Most of them have been fed by a cluster of digital pseudo-media (Rathnayake, 2018), created worldwide in the last few years, whose aim is to serve as a loudspeaker for far-right parties and collectives, but at the same time to take advantage of the economic gains of the clickbait economy (Munger, 2020).

Among a plethora of definitions for alternative media (Wasilewski, 2019), most emphasize the aim of these outlets to present unconventional coverage of the social reality, unorthodox compared to the offering of the mainstream media. The criticism offered by the former involves the newsworthiness factor as well as the production and distribution process (Holtz-Bacha, 2020). “Alternative journalism proceeds from dissatisfaction not only with the mainstream coverage of certain issues and topics, but also with the epistemology of news” (Atton and Hamilton, 2008: 1). Alternative media challenge the power of mainstream media and try to reverse the leading role of political and economic issues and actors, in order to empower social groups usually silenced and marginalized (Atton, 2008).

The terms “alternative media,” or “alternative journalism,” have been associated with left-wing activism since the 1970s when many “left-wing movements founded their own media outlets to counter mainstream media companies which were seen as a part of the establishment” (Haller and Holt, 2019: 1868). Some researchers, however, have noted the ambiguity of these terms and presented more suitable options, such as “community media,” “radical media,” “citizen media” or “activist media” (Downing, 2001; Rodríguez, 2001; Waltz, 2005). Controversy is especially acute since “alternative” is also associated with far-right media platforms that portray themselves as “alternative” to mainstream media and politics (Wasilewski, 2019). Figenschou and Ihlebaek highlight the “upsurge” of far-right alternative news providers over the last decade (2019: 1223). Heft et al. add that “despite being a rather new phenomenon, right-wing alternative news sites have rapidly become a cornerstone of the broader right-wing digital news infrastructure” (2019: 3). In fact, they present themselves as “journalistic outlets in their own right” (2019: 3), rather than mere opinion suppliers (Benkler et al., 2017).

Unlike the original progressive counter-hegemonic media, right-wing outlets fall short of strengthening democratic culture (Downing, 2001), empowering their users (Wasilewski, 2019), or encouraging openness. As emphasized by Atton, they represent “a community with closure, where the principles of authoritarian populism prevent any meaningful debate and work against any notion of democratic communication, insisting instead on hierarchical control” (2006: 575). The “relative absence of creativity, freedom and exploration of ideas and arguments,” “with similarly curtailed forms and styles of presentation and structure” (Atton, 2006: 575) focus on the “collective repetition” of stereotypes (Wasilewski, 2019).

Haller and Holt (2019) affirm that most research on alternative media focuses on the left-wing spectrum and its positive effect on democratic discourse, “inspired by anti-global, anti-capitalist viewpoints” (Figenschou and Ihlebaek, 2019: 1223). Nonetheless, other studies suggest that they are also linked to conspiracy theories, disinformation and populism (Van Prooijen et al., 2015), even if this reality is more prominent among right-wing media (Krouwel et al., 2017; Douglas et al., 2019). Until recently, little attention has been paid to right-wing media (Atton, 2006; Haller and Holt, 2019; Heft et al., 2020). However, the role of the Breitbart News in the 2016 United States Presidential elections and the increasing number of digital platforms in diverse countries has raised awareness of the relationship between the rise of populism and hyper-partisan media (Benkler et al., 2017; Wells et al., 2020).

Although the term “alternative media” has been associated with the “far-right media” (Atton, 2006) or “hyper-partisan media” (Benkler et al., 2017), its ambiguity prevented us from adopting the concept. We consider the term “pseudo-media” to be more appropriate, as these outlets mimic “compositional forms and styles used by mainstream journalists” (Rathnayake, 2018), while infringing journalistic conventions and mixing information, commentary, and ideology (Del-Fresno-García, 2019). This term is also consistent with research that highlights the blended nature of such texts that combine “moderate levels of sensationalism, disinformation, and partisanship to provide antiestablishment narratives” (Mourão and Robertson, 2019: 2077).

Unlike the positive connotation of alternative, the term pseudo-media clearly indicates the fraudulent character of the outlets that try to hide their real character. In fact, criticism directed at the mainstream media is not based on rational, democratic dialogue, but on “an emotional judgement that seeks to create mistrust” (Figenschou and Ihlebaek, 2019: 1224). By focusing the research on a country such as Spain, which is part of a media system defined as a Mediterranean, or as a Polarized Pluralist Model (Hallin and Mancini, 2004), the term pseudo-media is more accurate than any derivative term associated with partisan. Pseudo-media is also associated with “pseudo-information,” a concept that includes “all types (of) false or inaccurate information” (Kim and Gil de Zúñiga, 2021: 165). As the authors emphasize, “pseudo-information is not a counter concept to information. Rather, it is still under the umbrella of “information,” but discerns information causing harmful consequences or social externalities on information subscribers” (2020: 165).

Waisbord (2018) perceives the current communicative condition and populist beliefs in terms of “elective affinity” linked to the right-wing spectrum that embraces “post-truth.” In a hybrid media system (Chadwick, 2017), where traditional media are facing high levels of mistrust–82% of Spanish people have little or no trust in the media (Fernández, 2020)–, right-wing alternative media have found a breeding ground in which to flourish. The growing presence of the latter in terms of users and social media sharing can be considered as “one example of an ongoing polarization and fragmentation of the political discourse in liberal democracies” (Haller and Holt, 2019: 1668). Mistrust toward the mainstream media is related to the support of the populist agenda (Fawzi, 2019). Despite the vagueness of the term “populism,” it is often referred to by its ideological and communicative style (Schulz et al., 2018; Boberg et al., 2020). In this sense, it is characterized as a “thin-centered ideology” (Mudde, 2004) with “three sub-dimensions: anti-elitism attitudes, a preference for popular sovereignty, and a belief in the homogeneity and virtuousness of the people” (Schulz et al., 2018); and, on a communicative level, by its focus on “emotion-eliciting appeals” (Wirz, 2018).

The aim of this paper is to analyze the right-wing pseudo-media ecosystem in Spain regarding disinformation provided in relation to the coronavirus issues. Our study harnesses an important source, which is web-based content from digital outlets that try to imitate the formal aspects of the news media, yet produce misleading, biased, and polarized content that contributes to the problem of disinformation on fundamental issues such as public health. This research attempts to offer insight into the issues and frames in which the pandemic has been presented in several right-wing pseudo-media outlets, in order to know whether they adopt populist strategies and how they exploit the pandemic. The study adds a comparative perspective to this emerging field of research and contributes to a better understanding of the communicative ecosystem.

Materials and Methods

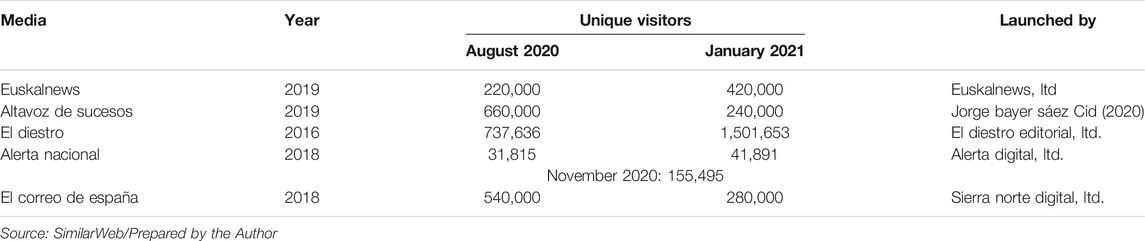

This study is based on the analysis of five right-wing digital outlets (Table 1) that are prominent in the Spanish disinformation ecosystem. Based on an extensive search of online information and bibliographic references (Hernández Conde and Fernández García, 2019; Vila Márquez, 2020), we first compiled a list of potential outlets to include in the research (11). From this group, we finally selected five: 1) digital news providers offering at least a rudimentary form of “current, nonfiction content with a given periodicity”; 2) the inclusion of a self-description as alternative, or anti-mainstream, among others; 3) a right-wing adscription explicitly stated or displayed in their topic focus, and 4) country-based, in this case Spain (Heft et al., 2020: 28). The selection added two more prerequisites: their regular activity between March 2020 and February 2021, and the ability to conduct specific word searches in their archives. Based on these requirements, outlets such as Diario Patriota, Despiertainfo and Caso Aislado were discarded due to their lack of activity or regular updating. Sites not offering a consistent system of word searches were also rejected, such as Mediterráneo Digital or La Nación Digital, as well as one that described itself as a “personal blog” (Contando Estrelas).

Although El Diestro was the only outlet that openly admitted being the “benchmark newspaper of the Spanish right,” the ideological background of the other four is also connected to right-wing extremist ideology. In spite of their self-presentation, an assessment of the founders’ identities clearly reveals links to far-right ideology. In fact, Euskalnews was launched by David Pasarín-Gegunde, leader of the Liga Foralista party, a Basque version of far-right ideology (Del Moral, 2020). El Correo de España is led by Eduardo García Serrano, who worked in the past for different far-right media, and portrays himself as a “Falangist.” The team of collaborators includes a wide group of names associated with the remains of the dictatorship, and even includes the president of the Francisco Franco National Foundation, dedicated to extolling the figure of the dictator. The organization also channels its activity through the SND Editores publishing house, which is dedicated to far-right topics and actors. Altavoz de Sucesos is owned by Jorge Bayer Sáez (Cid, 2020), founder of Diario Patriota and Caso Aislado, both characterized by the spread of disinformation (Ramírez and Castellón, 2018). Alerta Nacional and Alerta Digital both belong to Armando Robles, an entrepreneur who portrays himself as the “Spanish Donald Trump,” who was also the previous communication manager of Jesús Gil, a populist businessman and politician during the 1990s (Del Castillo, 2020).

Despite ideological connections, the analyzed outlets assure their journalistic independence. Euskalnews affirms that it offers “current affairs news in the Basque Country without censorship.” Similarly, El Correo de España portrays itself as “a newspaper independent of any political party that aims to fulfill the commitment with our readers.” Moreover, Altavoz de Sucesos underscores that they “work daily to report all national and international news with a team of professionals who work from all parts of Spain to bring all the events to your home first.” The newsroom team has just three people and the director. Considering the above, we pose the following question:

RQ1: What are the characteristics of the pseudo-media?

In order to obtain a sample for analysis, three data selections were made, coinciding with the three first waves of the coronavirus in Spain, according to the Spanish Ministry of Health (2020). Data gathering was carried out at the peak of each wave–March 15th, 2020, October 20th, 2020, and January 15th, 2021–and included the 30 following days as well. The first step in selecting the sample was to search for the word *covid* on the internal search engine of each media archive to identify the news items published in the periods analyzed. We completed the sample with a new search with specific terms: *lockdown*, *mask*, and *vaccine*, in order to access the main articles published about the pandemic (N = 1,330). After removing duplicates and press release news, the sample was reduced to N = 1,009 articles, including Euskalnews (EU, n = 152), Altavoz de Sucesos (AS, n = 79), El Diestro (ED, n = 89), Alerta Nacional (AN, n = 413), and El Correo de España (CO, n = 276). The links to these items were saved in an Excel file. The following research questions have been analyzed by using qualitative and quantitative methodologies:

RQ2: What are the most relevant topics addressed in quantitative terms?

RQ3: What are the dominant frames regarding pandemic topics?

Content analysis of the final sample involved analyzing each text completely to identify 1) the main topics of the items; and 2) the frames associated with the topics. To guarantee reliability and consistency in the qualitative analysis, the one codifier used performed a test-retest of 33% of the registers until complete agreement was reached before continuing to complete the entire data codification. With the aim of delving into the arguments highlighted by the pseudo-media, once the main topics were determined among the publications gathered, we analyzed which frames were used to refer to those topics in order to discover the main ideas associated with each. To frame something involves a process of “selection” and “salience,” by which the definition, diagnosis, moral evaluation, and proposal of solutions concerning certain topics are developed (Entman, 1993: 52). Framing analysis (Scheufele, 1999; Tankard, 2001) has been part of the communication research field in recent decades for the purpose of gaining knowledge regarding the central message of a news item and the proposed interpretation.

Results

The three following sections present the quantitative and qualitative results of the research conducted in order to answer the research questions above.

Pseudo-Media Characteristics

The five sites analyzed can be defined as pseudo-media, considering that even if they seek to mimic the appearance of traditional media, none of them respects the minimum standards of journalistic practice (Table 2). Firstly, the published texts almost never identify the sources and, when they rarely do so, the data is based on social networks or unreliable outlets, as they refer to other pseudo-media, mostly from other countries. However, in some cases they provide the source, but it is not the most appropriate for assessing the risk of infection after vaccination [i.e., an orthopaedic surgeon rather than an epidemiologist (Euskalnews, January 23, 2021)], or they offer a misleading interpretation of the data obtained from official sources [i.e., El Correo de España published that in 2020 fewer people had died in Spain than in the five previous years (January 24, 2021)]. The absence of ethical and professional criteria is reflected in the fact that most of the articles seemingly presented as news are not bylined. Secondly, the texts included on the sites do not meet the professional rule of separation between news and commentary. In fact, they rely on biased headlines that explicitly show an orientation toward right-wing extremist ideology. Thirdly, their publications are detached from deontological codes and ethical concerns (i.e., the International Federation of Journalists (IFJ, 2020), particularly regarding sensitive topics such as public health or migration.

The outlets analyzed are not only examined and contested frequently by fact-checking platforms in Spain due to their overriding tendency to publish disinformation, but some have even been involved in legal proceedings as a result of their activity (Sánchez Castrillo, 2021). Their willingness to portray themselves as anti-mainstream (Heft et al., 2020) encourages them to display the image of being the victims of censorship. On its Facebook webpage, Euskalnews claims it is “the most censored media on the internet,” and adds, “There must be a reason.” Likewise, El Correo de España asserts on the same social network that it “has become the main communication media with a dissident line in Spain and is being persecuted by Facebook and the rest of the verifiers,” referring to the fact-checking platforms.

The five sites show large discrepancies, not only in the number of items published on the covid-19 issue, but also regarding the type of texts disseminated. Two principle models can be identified. The first, which El Correo de España follows, is characterized by its productivity, with nearly 550 articles published and two clear approaches: one focused on press release news (n = 272) and another on a mix of pseudo-information and commentary with a clear bias toward far-right ideology (n = 276): “Morocco invades Spain since 1975: the Canary Islands, its springboard” (November 20, 2020) or “Squandering the money we do not have with subsidies to “feminazi issues”” (November 9, 2020). Considering the aim of this research, we analyzed only pseudo-information and commentary, in order to avoid distorting the data. The second model, which the four remaining outlets follow, also involves differences in production and style. Euskalnews and Alerta Nacional mostly publish non-bylined pseudo-information while the majority of the articles gathered from Altavoz de Sucesos are bylined. El Diestro offers pseudo-information and commentary that is indistinguishable one from the other, with irregular criteria for bylining them. The models identified are relevant in order to show the diversity of options adopted and the need to avoid generic approaches.

Issues

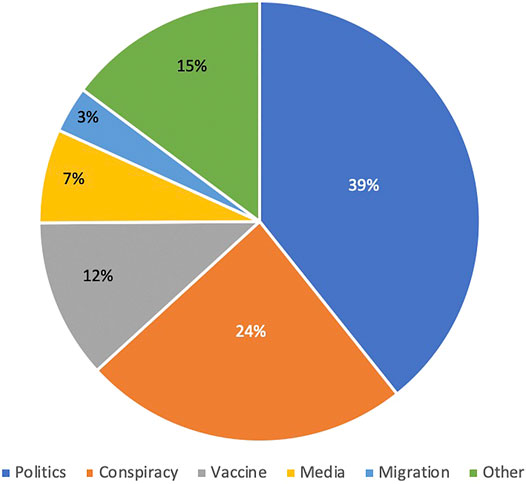

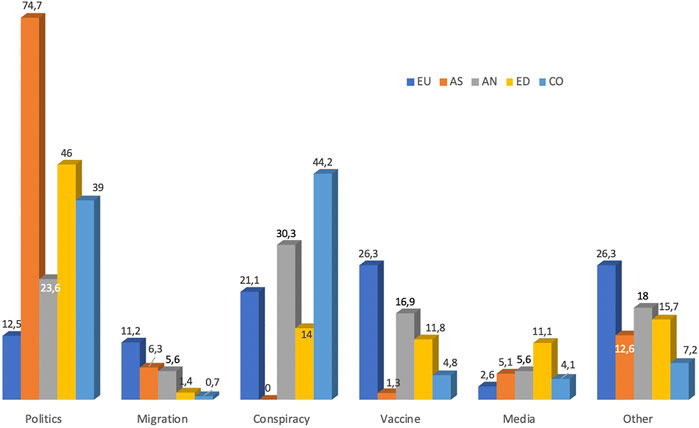

In order to answer RQ2, the news items were first classified to define the main issues covered. Five main issues were identified, in addition to a sixth that included other. We proceeded by assigning one issue to each item, except in the case of 16 items, which were linked to two issues (N = 1,024). The results show that politics is the main issue among the outlets analyzed, composing four out of ten of the items gathered (see Figure 1). The majority of them refer to the representatives of the Spanish government, mainly the Socialist Party President Pedro Sánchez and the second Vice President Pablo Iglesias, leader of the Podemos party. Conspiracy theories regarding the origins, interests, and decisions made about the pandemic appear in nearly a quarter of the texts, while the vaccination program to fight it are present in 11.7%. Finally, nearly 7% of the items focus on criticism directed at the media and journalists for their coverage of the coronavirus, while migration (an issue that is a priori issue and not even linked to the pandemic),–received attention as well.

Even if the pseudo-media rely on similar strategies to feed disinformation, they are not homogeneous in their publishing interests (Figure 2). The vaccine was the main topic for Euskalnews (26.3%). However, it was irrelevant for Altavoz de Sucesos. Nonetheless, the latter outlet focused on politics, with 75% of the items devoted to that topic. El Diestro also showed interest in politics, though to a lesser extent, without downplaying the importance of conspiracy theories and vaccines. The former, conspiracy theories, was the most relevant topic for El Correo de España and Alerta Nacional, with politics being the second most important issue for both of them.

Frames

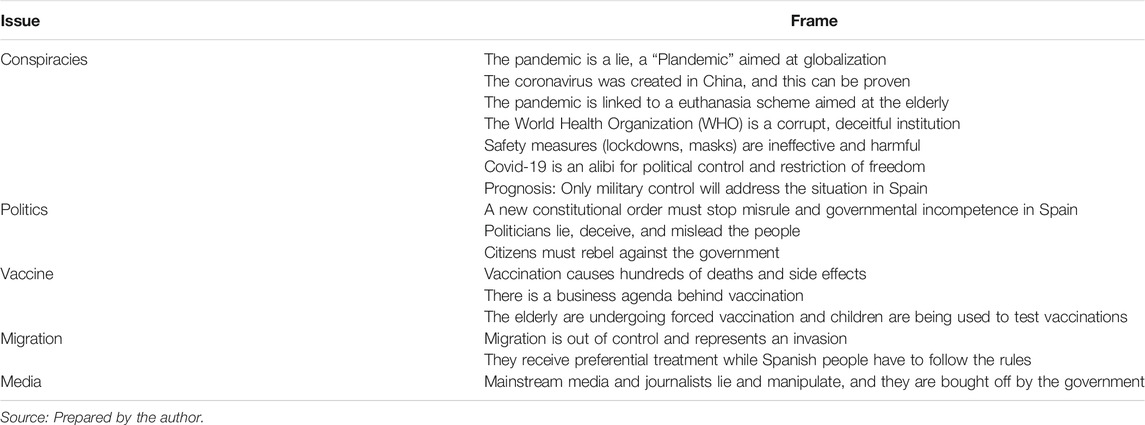

After having identified the issues, a framing analysis was carried out in order to determine which values and interpretations are present in each pseudo-media. The qualitative research developed in the following sections is summarized in Table 3. The issue of conspiracy theories was the most productive, with six associated frames, while vaccination and politics were each linked to three frames. Despite the fact that the frames associated with vaccines involve some kind of conspiracy, the issue Vaccine has been disassociated from Conspiracy, as it was considered to be a stand-alone issue.

Euskalnews

This media outlet focuses on the negative effects of vaccination by presenting the vaccine as the cause of hundreds of deaths and side effects, as well as new outbreaks of the disease. This is done through the use of misleading headlines that link receiving a vaccination with increased mortality, disregarding the nuance that there is no evidence to support an allergic response: “The coronavirus vaccine can kill a person in 25 min: it happened in New York” (February 10, 2021). The site gathers this pseudo-information from foreign countries, relying on second hand sources from unreliable outlets (mpr21. info, Daily Mail), without additional verification or contextualization for the Spanish audience. It also echoes all types of objections and warnings, regardless of the background or specialization of the doctor cited–“Does Pfizer’s vaccine increase the risk of COVID infection? A French doctor believes a link exists” (January 23, 2021)–or taking advantage of a clickbait strategy in a headline by stressing the alleged scoop that is not even developed in the text: “Bombshell! The WHO questions the effectiveness of the vaccines due to new virus mutations” (February 11, 2021).

The site also employs a sensationalist style to highlight a second frame: the forced vaccination of the most unprotected members of the society, which include the elderly–“Two Alicante judges order forced vaccinations of two disabled elderly people despite strong opposition from their families and assistants: Scoundrels!” (January 27, 2021)–, and minors–“Six-year-old children used as guinea pigs to experiment with the controversial Oxford-Astrazeneca vaccine” (February 14, 2021). Both headlines are misleading because they leave out key information.

In Euskalnews, conspiracy theories play a key role, with three focuses of attention: the origins of the pandemic, the corruption of the different institutions managing the crisis, and the ineffectiveness of the measures taken to combat it. The thesis of a laboratory-created virus not only insists on referring to the pandemic as the “Chinese virus” (January 20, 2021), but includes headlines that explicitly appeal to the readers: “In China they celebrate Halloween with massive parties without masks or social distancing. Are they joking with us?” (April 2, 2020), or they insinuate that there is evidence that will soon be announced by relying on a British tabloid: “Daily Mail claims Pompeo will reveal evidence about the true origin of the Coronavirus” (January 15, 2021). The second frame insists on the idea of corrupt and deceitful institutions: “More corruption in the WHO. One of its researchers received money from the Communist party of China” (February 14, 2021). The willingness to undermine the legitimacy of the WHO is also expressed in the following example: “The WHO ridicules everyone about the origin of the coronavirus. Now they say it came from foreign frozen products” (February 2, 2021). Both the start of the headline and the text express an explicit ideological position over the issue, yet they fail to mention that it was published by Breitbart.

By giving voice to scientists who are not specialists in epidemiology, such as the dean of the Euskadi Professional Institute of Biologists, this media outlet frames the ineffectiveness of the measures and the economic interests involved. More than a third of the items gathered are related to this issue. While stressing that the source is a “leading member of the Euskadi Biologists organization” (October 28, 2020), the outlet also reproduces the tweets of a Spanish singer to reinforce the view that the pandemic aims to scar the country: “They lie about figures and deaths” (January 20, 2021).

It is also important to underscore the focus on migration, whether to note the contagion among minors in reception centers or to criminalize them in various ways, among which is not having a home where they can stay during lockdown. This fact is used to show them as privileged and not subject to the strict regulations: “Coronaprivilege: seven violent magrebies roam uncontrollably through Bilbao while the rest are bored at home” (March 27, 2020).

Altavoz de Sucesos

Politics plays a central role for this media outlet, as three quarters of the gathered items focus on the coronavirus topic. They represent a collection of strongly critical statements that frame governmental incompetence and serious irregularities: “The Supreme Court puts the Sánchez Government on the ropes: it will analyze its disastrous management of the coronavirus” (April 1, 2020), publishing misleading headlines that are unsubstantiated in the text: “The Imperial College confirms Government negligence: the 8M triggered the contagion of up to two million people” (April 2, 2020). A second frame stresses the aim of left-wing parties to curtail freedom of expression–“Podemos presents an initiative to monitor social networks and eliminate hate messages” (October 25, 2020)–and to act as censors of political freedom: “The left uses the riots throughout Spain to call for VOX to be outlawed: “It’s a criminal organization”” (November 1, 2020). To emphasize these ideas, Altavoz de Sucesos echoes a plethora of attacks expressed by political opponents, gathered on social networks, and introduced by using demeaning language: “Trump tramples Pedro Sánchez and points to his administration as an example of what the United States should avoid” (March 31, 2020), “Isabel Díaz Ayuso puts Pedro Sánchez in his place in the online meeting” (March 29, 2020), or “Toni Cantó dismantles communist totalitarianism in six wonderful minutes that sink Podemos” (October 29, 2020).

A third frame related to politics shows their members as cynical, wasteful public sector managers who are “incapable of stopping the increase of coronavirus deaths”: “The Government spends 28,000€ to install screens in official cars to protect its members from the coronavirus” (April 14, 2020), “The Government of the PSOE-Podemos coalition spends nearly 56 million euros a year on “silver-spooned” personnel and advisers” (October 31, 2020), or “Irene Montero wastes a fortune on a frivolous study that concludes that the color pink oppresses girls” (October 29, 2020).

Though to a lesser extent than politics, the issue of uncontrolled migration is severely criticized by this outlet–“The lack of immigration control continues: more than 350 illegal immigrants arrived in Spain in the last few hours” (November 2, 2020)–and blames migrants for the unrest and thefts during a protest against coronavirus restrictions, while getting preferential treatment: “The Ministry of Justice offers its condolences to Muslims and ignores the more than 13,000 deceased Spaniards” (April 6, 2020). Attacks on the mainstream media are clearly framed in this headline: “The Government will give 15 million in subsidies to TV channels such as La Sexta and Antena three in the midst of the coronavirus pandemic crisis” (March 31, 2020).

Alerta Nacional

Conspiracy theories are built on the foundation of para-normality. The pandemic is predominantly framed as a “previously anticipated” phenomenon, a “prophecy fulfilled” (March 22, 2020), heralding the “apocalypse” (March 17, 2020) and causing a “viral holocaust” (March 20, 2020) with Biblical references to the “Angel of Death” (March 19, 2020). However, at the same time, covid-19 is portrayed as “a deliberately created Chinese virus,” “hidden” by the “communist regime” (April 10, 2020). Secondly, conspiracy theories are framed within the argument of the “extermination of the elderly”: “(TREMENDOUS VIDEO) They are letting the elderly DIE in nursing homes without treating them: VERY RESPONSIBLE GOVERNMENT” (March 31, 2020). Moreover, they insinuate a type of elderly genocide: ““The old must die.” Netherlands criticizes Spain and Italy for admitting “people who are too old” into the ICU” (March 30, 2020). The plot ends with a third frame that also emphasizes that left-wing parties in power in Spain take advantage of this situation in order to “nationalize banks” (March 17, 2020), “conduct a coup d’état” (March 20, 2020), or force an “Orwellian society” (April 13, 2020). Globally, the pandemic will be the alibi for various constraints: refugee camps for violators of COVID rules, compulsory vaccination, and identification: “The Number of the Beast in everyone: Bill Gates plans to implant chips in all humans to “fight” COVID 19” (March 28, 2020).

Although Alerta Nacional does not publish items framing vaccination as having serious adverse effects, it insists on its ineffectiveness: “The pharmaceutical company MERCK abandons the development of its vaccine AND IT TELLS THE TRUTH! “Catching the virus and being cured is much safer and more effective”” (February 1, 2021). However, the site extols the virtues of the Russian vaccine Sputnik V by relying on previous items published by Russia Today (RT). Alerta Nacional frequently includes capital letters to stress polarizing messages.

Items related to politics are associated with two frames. The first portrays an incompetent government that lies to its citizens, buys fraudulent tests, and does not implement the economic measures required, while the number of covid deaths and infections increases. The second insists on the scarce criticism received, both from civil society –“A nation of sheep begets a government of wolves” (March 30, 2020)– and from political opponents –“This is how the Government LIES to us with the permission of the drooling, dumb opposition from the PP: COME IN AND SEE! THEY LAUGH AT YOU!” (October 25, 2020).

Despite the fact that the media issue only includes five items, this outlet does not miss the opportunity to accuse the mainstream media of complicity with the government: “Sánchez forces the self-employed to pay two more installments while preparing 100 million euros in advertising for the media mafia” (April 8, 2020), and they attack any effort to stop disinformation by echoing other pseudo-media along the same lines.

El Diestro

Politics is the main concern of El Diestro, with nearly 40% of its publications focused on the issue. The analysis shows that two frames play a central role. The first is the thesis of Spanish “misrule” in the hands of an irresponsible government that despizes its citizens. In order to build this argument, this outlet not only rejects any intention to inform, but also uses abusive expressions to discredit the government: “We are in the hands of lunatics!!” (April 5, 2020), “(President) Pedro Sánchez laughs during his speech in Congress. Can a person be more despicable?” (April 9, 2020) or “Carajillito’ (coffee with cognac) (minister of Transport and Mobility José Luis) Ábalos demonstrating, once again, that if he bites his tongue he will be poisoned” (April 13, 2020). To reinforce the attacks, El Diestro reproduces a wide variety of critical expressions found on social networks, particularly Twitter and YouTube, adopting a type of war language that fuels political mistrust: “How the rabid left lies, manipulates, and invents” (April 2, 2020). Secondly, this media focuses on economic measures in order to accuse the government of lying and making false announcements, particularly toward self-employed workers: “The lie of 200 billion euros in public investment to reactivate the economy” (March 24, 2020), or “Never before seen: The government of Pedro Sánchez THREATENS the self-employed to pay” (March 22, 2020).

Conspiracy theories had a secondary role in the texts gathered. On the one hand, the goal was to stress the limitation of rights and censorship. This frame is expressed in headlines such as, “The declaration of a state of alarm violates our fundamental rights” (March 19, 2020), or “The genocidal coup government of Pedro Sánchez” (March 21, 2020), or “Sánchez and the Gag Law of the 21st century” (April 10, 2020), which emphasize that the government took advantage of the health situation to impose their policies, even on sensitive issues like justice –“With the excuse of the coronavirus, the government controls Justice” (March 28, 2020) –or property –“Scandalous!!! Be very careful with this: In today’s BOE, the communist government charges private property” (March 31, 2020) –or freedom of expression–“Be careful with what you publish because the Government, with your taxes, is going to censor you in networks” (April 11, 2020). References to the use of masks, lockdowns, and globalism can only be found in texts gathered at the end of 2020 and the beginning of 2021–“What is Globalism? This is how it all began, and the reasons why the current situation around the world is taking place, and the RESET (Davos 2021)” (October 26, 2020). On the other hand, the second frame is connected with conspiracy theories, and it links the pandemic to a euthanasia scheme, especially aimed at the elderly–“Future elderly, current corpses”–and insinuates an attempt to hide it: “They want to hide the real pain that exists in Spain, these are the photographs that the government doesn’t want you to see” April 8, 2020).

In absolute terms, El Diestro is the media outlet that focuses more attention on the vaccination issue. Moreover, the items are concentrated in one month, coinciding with the beginning of the program. This media includes approximately fifty items that frame vaccination as a danger with the potential for hundreds of deaths and side effects, linked to murky economic interests as well. The first idea is encouraged by using alarming pseudo-information from different countries as well as from Spanish retirement homes, with misleading headlines that refer to the death of people not yet immunized. The second idea is framed by headlines that insist that vaccination is a business ploy–“The big historical lie: first the vaccine was created, and then the pandemic, not the other way around” (January 28, 2021), or “Pfizer announces staggering revenues for the year from vaccines” (February 02, 2021)–or asserting that denouncements about some politicians being vaccinated irregularly are uncertain and are intended “to create the desire to do so among the population” (January 24, 2021), in a kind of “childish psychological game” (January 29, 2021).

The frame that accuses traditional media and progressive journalists of lies and manipulation, El Diestro attacks both groups. However, at the same time it praizes those who criticize the coalition government of the Socialist Party and Podemos, or have been closed down due to accusations of disinformation. Language connotation is used to describe prominent TV anchors–“the submissive Xavier Fortes” (April 14, 2020) or “Ferreras continues to demonstrate a pathetic and ridiculous sectarianism that is even embarrassing” (April 14, 2020)– or to make a joke using the name of the fact-checking platform Newtral, launched by a journalist: “Ana Pastor, the Newtrolera” (April 10, 2020). The same journalists are always displayed as being at the service of the government in power and receiving benefits for it: “Scandalous: The government intends to pay for the services rendered by Wyoming, Mejide, Griso, Ferreras, Pastor, Vázquez and company” (March 31, 2020), while accusing them of giving misleading information about the most conservative representatives: “The progressive press never stops lying about Díaz Ayuso” (April 14, 2020).

Xenophobic discourse is present when framing migration as an “organized invasion” (November 8, 2020) to “destroy us” (Spanish culture) (November 15, 2020), mixed with references to the alleged privileges of migrants compared to the restrictions of local people: “The new affront of the government: Ramadan yes, Holy Week no” (April 11, 2020).

El Correo de España

This site has turned the coronavirus into a great opportunity to disseminate an endless variety of conspiracy theories surrounding the pandemic, devoting half of its texts to the idea. El Correo de España builds its strategy with five interlinked frames. The first, expressed by the term “Plandemic,” refers to a denial strategy that rejects not only scientific explanations, but even deaths. Mixing unconnected data, opinion, and a typical clickbait headline, the texts “Ten certainties that confirm a Plandemic” (October 18, 2020), and “Remembering thirty pieces of evidence that demonstrate the Big Lie of the coronavirus” (October 28, 2020), underscore the idea that “The pandemic is a lie: fewer people died in Spain last year than in the last five” (January 24, 2021).

The second conspiracy frame emphasizes the thesis that the pandemic was created in China and uses different expressions with ideological and xenophobic biases that link the “yellow virus” (April 13, 2020), the “communist dictatorship” (March 31, 2020), and the “communist putsch” (March 26, 2020) with a plan to replace the “cosmopolitan, liberal West.” Though possibly inconsistent with the previous statement, as a third frame this media insists there is a “complot” designed and orchestrated by a “New Global religion” (November 14, 2020) associated with the Global Economic Forum and powerful businessmen such as Bill Gates and George Soros, aimed at a “Global reset” and the “extermination of nation-states” (March 15, 2020). Conspiracy theories are also supported by using a strategy of fear toward measures that are paradoxically causing the deaths: “Lockdown has killed more elderly than the alleged covid-19” (November 12, 2020).

The fourth frame highlights that the coronavirus is “the perfect alibi to establish a communist dictatorship” (March 31, 2020), to control justice, sink the economy, and end private property. Along these lines, it refers to the measures taken as examples of the “covidian dictatorship” (January 25, 2021) and crimes committed against humanity. The site calls the lockdown a “house arrest” (October 21, 2020), and the state of alarm declaration a violation of fundamental rights. After portraying this chaotic scenario, the fifth frame emerges as the only option to overcome the situation with the following headline: “For massive evil, the military is the remedy” (April 7, 2020). Far-right appeals to military intervention are common in the texts analyzed, including one entitled, “There is only one way to save Spain” (March 28, 2020), which concludes that the country is “at war,” and compares “today’s dictatorship with the authoritarian social democracy of the Franco regime” (February 3, 2020).

The permanent attack on government decisions characterizes the first frame associated with the issue of politics, with no argument other than insults, as in the case of “The ever-so-evil left,” “Not just fools, even worse,” or “The Government is the real virus in Spain” (January 24, 2021). The thesis of the pseudo-media, which has launched a “call for a new constitutional order” (November 5, 2020), is linked with the last conspiracy frame, especially when restoring references to the dictatorship–“The desecration of Franco’s tomb was only the first step in everything we are seeing, and everything yet to come” (January 16, 2020)–or, in the article “Catatonic Spain,” the call for “the emergence of leadership without fear of anything, with firm convictions” (October 31, 2020), released by the president of the Francisco Franco foundation. Following the previous frame, the second stresses that the government deserves harsher criticism from citizens–“Finally a neighborhood federation protests against the Sánchez Government” (January 26, 2021), or “The Government deserves more protests than (King) Felipe VI” from political opponents. While the most extreme are applauded–“VOX is not a political caste, it is leading by example” (April 4, 2020), or “Madrid resists social-communist harassment” (November 11, 2020)–lukewarm criticism is questioned: “Casado whitewashes the Government” (October 24, 2020).

Though less so than the previous one, references to the mainstream media emphasize the frame of buying allegiance to silence the media and connivance with politicians, as this headline suggests: “The big media press the Government: “Either subsidies or criticism for the management of Covid-19” (May 5, 2020).

Discussion and Conclusion

The relevance of this research is founded upon the increasing levels of disinformation and polarization and their implications for democracy (Bennett and Livingston, 2018; Casero-Ripollés, 2020), particularly in a country such as Spain with low levels of trust in the media (Newman et al., 2019). Dissatisfaction with the mainstream media is an important driving force (Müller and Schulz, 2021) in the emergence of these pseudo-media outlets. This situation has been occurring simultaneously with an upsurge of far-right wing parties such as Vox and the latter’s entry into Spanish democratic institutions for the first time in 4 decades (González-Enríquez, 2017). From the time it entered the Andalusian Parliament in December of 2018, this party has obtained representation not only in various regional parliaments, but in the Spanish National Parliament as well, where it has consolidated its role as the third political force based on representation.

Although certain characteristics define the five media analyzed as “pseudo-media,” they are not homogenous in their style or editorial focus, nor even in their frequency of publication, which reveals diverse patterns (Haller and Holt, 2019). This indicates a variety of models, strategies and interests, and prevents “simplistic interpretations of hyper-partisan media” (Heft et al., 2020: 38). Our research shows two organizational models that range from a more conventional appearance, regular publishing, and structure (El Correo de España and El Diestro), and to a lesser extent Alerta Nacional, Altavoz de Sucesos, and Euskalnews. El Correo de España, for instance, presents a dual model that combines press release news–mainly from local and regional institutions of Madrid in the hands of the Popular Party–together with a blend of pseudo-information and commentary. These results are consistent with research that stresses the increasing difficulty that audiences have in differentiating between hyper-partisan and standard online news (Heft et al., 2020).

A clear emphasis on the issues and the frames used to outline such issues show the heterogeneity of editorial interests regarding the coronavirus coverage that range from turning the health crisis into an opportunity to attack the Spanish government to focusing on conspiracy theories. While criticism of the government and claims of a new political order in Spain are more prevalent in Altavoz de Sucesos and El Diestro, conspiracy theories are mostly associated with Alerta Nacional, Euskalnews, and El Correo de España. In the last case, frames discrediting the progressive government are also significant. Euskalnews completes this approach with two common obsessions of far-right wing media, such as vaccines (Douglas, 2021) and migration (Rone, 2020), even if its connection to the coronavirus is tangential. In all cases, one can clearly identify the pattern of a populist (Müller and Schulz, 2021; Rae, 2020) and polarized discourse (Stroud, 2010), aligned with far-right ideology.

The populist approach is framed by using expressions that describe the elites of politics, science, and the media as betraying, deceitful people (Schulz et al., 2018). The Spanish government, as the representative of the political elite (even worse, a progressive left-wing coalition) is the target of attacks due to its incompetence and deception of citizens. The political authorities managing the health crisis are portrayed not only as incapable of carrying out the task, but as detrimental to the people, causing them severe harm and even exploiting the situation for their own political interests, limiting the fundamental freedoms of their citizens. Though not the first target, international institutions such as the WHO are portrayed as corrupt and contemptible (Mudde, 2004).

Criticism of the mainstream media, one of the cardinal points of the populist strategy (Haller and Holt, 2019), is easy to recognize with frequent accusations and personal attacks on renowned journalists and TV anchors, who presumably conceal relevant information in complicity with the establishment and, accordingly, receive financial support from the Spanish government. However, the pseudo-media analyzed rely on their “media peers.” They use diverse online outlets and social media programs on platforms as references–from Spain and abroad–to feed and support their content. That not only reinforces their editorial viewpoint but also provides feedback to the far-right alternative ecosystem and, consequently, enhances selective exposure and the echo-chamber effect (Bruns, 2017).

Our research also confirms the link between populism and disinformation (Müller and Schulz, 2019; Corbu and Negrea-Busuioc, 2020) as the items analyzed are mostly developed on the basis of using misleading headlines (Mourão and Robertson, 2019), or even reframing the mainstream news media (Holt et al., 2019). The hostility toward expertize as an expression of scientific elitism is replaced by the proliferation of quasi or pseudo-experts. Curiously, these outlets quoted several scientific sources with two prerequisites: their lack of specialization–doctors, but not epidemiologists–and their contribution to feeding conspiracy theories. Moreover, they capitalized on the superabundance and accessibility of pandemic-related data to exacerbate the “systemic and long-standing” crisis of expertize (Brubaker, 2020: 6).

The ideological strategy is reinforced by a communicative style that relies on a sensational approach aimed at eliciting emotion (Wirz, 2018). To this end, they capitalize on clickbait patterns to present headlines characterized by expressiveness, appeals to the reader, and colloquial language (Palau-Sampio, 2016). In fact, headlines not only mislead, but they also emphasize the ideological content by means of vocatives, capitalizations, and frequent abusive expressions. The latter often occurs when the main people involved are representatives of the political and media realm, who represent the corrupt elite (Mudde, 2004). Likewise, this is a clear expression of the political polarization fueled by these pseudo-outlets. The use of belligerent language to harshly criticize certain actors turns the public sphere into a battlefield, and prioritizes confrontation over dialogue and the exchange of ideas (Stroud, 2010), with obvious costs to issues such as public health and the pandemic (Makridis and Rothwell, 2020).

The three-fold rejection of politics, expertize (including the WHO), and the mainstream media allows for a plethora of pandemic disinformation, bolstered by pseudo-information that even rejects the very existence of covid-19, thereby confronting these populist outlets with a paradox. Ordinarily protectionist, they are challenging the restrictions and promoting skepticism toward the preventive measures (Brubaker, 2020), while polarizing audiences. Even more importantly, some of these pseudo-media are capitalizing on the complex scenario to fuel emotional responses by means of calling people to action and protest, and prognostic frames that encourage military intervention.

Despite the audience fluctuations of these five outlets, it is striking that they have reached 2.5 million monthly unique users (February 2021). Even if the research has noted that the consumption of these pseudo-outlets accompanies the use of other traditional media information (Rauch, 2015), it reveals a strong demand for this type of pseudo-information (Heft et al., 2020). The findings confirm, as Schulze suggests, that right-wing alternative online media “should not be underestimated or dismissed as a peripheral phenomenon” (2020: 16).

This research is not without limitations, and these should be addressed in future studies. Firstly, pseudo-media outlets warrant more research in order to understand their diversity and interests, as well as their characteristics at the organizational, structural, and financial levels, including the clickbait economy. Secondly, this research sampled five Spanish pseudo-media that focused on the pandemic, and consequently, it has not provided information regarding the entire scope of interests of these organizations. Moreover, the research focuses on right-wing outlets but does not explore the involvement of left-wing outlets in the pseudo-media ecosystem. Finally, it is essential for future studies to evaluate the impact of these pseudo-media outlets on the public discourse and their potential to polarize attitudes.

This article contributes to mapping out the far right-wing pseudo-media outlets in Spain and identifying their characteristics. The research carried out reveals a three-way relationship between disinformation, polarization, and populism. These pseudo-media not only publish half-truths and distorted information but also encourage polarization by means of war expressions and frames that repudiate political, scientific and media expertize. Rooted in populism, this strategy found a perfect breeding ground during the pandemic. Exploiting the potential of emotion, the pseudo-media has capitalized on this aspect as an opportunity to expand right-wing ideology cloaked in conspiracy theories and discourses against vaccination and migration.

Data Availability Statement

The raw data supporting the conclusions of this article will be made available by the authors, without undue reservation.

Author Contributions

The author confirms being the sole contributor of this work and has approved it for publication.

Funding

This project has benefitted from the support of the R and D project “The ecology of disinformation: the construction of fake news and its impact on the public space” (AICO2020/224), funded by the Conselleria of Innovation, Universities and Digital Society, Generalitat Valenciana 2020–2021) and from the “Art/Place/Economy to democratize society. Research placemaking for alternative narratives” (Trans-Making H2020-MSCA-RISE, 2017–2021).

Conflict of Interest

The author declares that the research was conducted in the absence of any commercial or financial relationships that could be construed as a potential conflict of interest.

References

Atton, C. (2006). Far-right media on the Internet: Culture, Discourse and Power. New Media Soc. 8 (4), 573–587. doi:10.1177/1461444806065653

Atton, C. (2008). “Alternative Media Theory and Journalism Practice,” in Digital media and Democracy: Tactics in Hard Times. Editor M. Boler (Cambridge and London: The MIT Press), 213–228.

Atton, C., and Hamilton, J. (2008). Alternative Journalism. Thousand Oaks, CA: Sage. doi:10.1002/9781405186407.wbiecc027

Bechmann, A. (2020). Tackling Disinformation and Infodemics Demands Media Policy Changes. Digital Journalism 8 (6), 855–863. doi:10.1080/21670811.2020.1773887

Benkler, Y., Faris, R., Roberts, H., and Zuckerman, E. (2017). Study: Breitbart-Led Right-Wing Media Ecosystem Altered Broader Media Agenda. Columbia Journalism Rev. 3. Available at: https://www.cjr.org/analysis/breitbart-media-trump-harvard-study.php.

Boberg, S., Quandt, T., Schatto-Eckrodt, T., and Frischlich, L. (2020). Pandemic Populism: Facebook Pages of Alternative News Media and the Corona Crisis--A Computational Content Analysis. arXiv:2004.02566 (Accessed March 5, 2121).

Brubaker, R. (2020). Paradoxes of Populism During the Pandemic. Thesis Eleven 164, 73–87. doi:10.1177/0725513620970804

Bruder, M., and Kunert, L. (2020). The Conspiracy Hoax? Testing Key Hypotheses About the Correlates of Generic Beliefs in Conspiracy Theories during the COVID-19 Pandemic. PsychArchives, 1–23. doi:10.23668/psycharchives.3158

Bruns, A. (2017). Echo Chamber? what echo Chamber? Reviewing the Evidence [Conference Presentation] 6th Biennial Future of Journalism Conference (FOJ17). UK: Cardiff UniversityAvailable at: http://snurb.info/files/2017/Echo%20Chamber.pdf (Accessed March 3, 2021).

Casero-Ripollés, A. (2020). Impacto del Covid-19 en el sistema de medios. Consecuencias comunicativas y democráticas del consumo de noticias durante el brote. Profesional de la Información 29 (2), 1–12. doi:10.3145/epi.2020.mar.23

Chadwick, A. (2017). The Hybrid media System: Politics and Power. Oxford: Oxford University Press. doi:10.1093/oso/9780190696726.001.0001

Cid, G. (2020). 1M de clics al mes por cabrearte: las webs de desinformación se disparan con el covid. El Confidencial. 08/05/2020 Available at: https://www.elconfidencial.com/tecnologia/2020-05-08/webs-desinformacion-trafico-bulos-extrema_2582735/ (Accessed February 18, 2021).

Cinelli, M., Quattrociocchi, W., Galeazzi, A., Valensise, C. M., Brugnoli, E., Schmidt, A. L., et al. (2020). The Covid-19 Social media Infodemic. Scientific Rep. 10 (1), 1–10. doi:10.1038/s41598-020-73510-5

Corbu, N., and Negrea-Busuioc, E. (2020). “Populism Meets Fake News: Social Media, Stereotypes and Emotions,” in Perspectives on Populism and the Media: Avenues for Research. Editors B. Krämer, and C. Holtz-Bacha (Baden-Baden: Nomos), 181–200. doi:10.5771/9783845297392-181

Del Castillo, C. (2020). El ex jefe de prensa de Jesús Gil burla a Facebook con su nueva página de fakes y ya planea “ponerla al servicio de Trump”. Eldiario.es. 13 February. Available at: https://bit.ly/3f2fjGx (Accessed February 19, 2021).

Del Moral, J. A. (2020). Así se cuelan los radicales vascos en las redes sociales locales. Gananzia5 August 2020. Available at: https://gananzia.com/asi-se-cuelan-los-radicales-vascos-en-las-redes-sociales-locales (Accessed February 21, 2021).

Del-Fresno-García, M. (2019). Desórdenes Informativos: Sobreexpuestos e Infrainformados en la era de la Posverdad. El profesional de la información 28 (3), 1–11. doi:10.3145/epi.2019.may.02

Douglas, K. M. (2021). COVID-19 Conspiracy Theories. Group Process. Intergroup Relations 24 (2), 270–275. doi:10.1177/1368430220982068

Douglas, K. M., Uscinski, J. E., Sutton, R. M., Cichocka, A., Nefes, T., Ang, C. S., et al. (2019). Understanding Conspiracy Theories. Polit. Psychol. 40, 3–35. doi:10.1111/pops.12568

Downing, J. D. H. (2001). Radical media: Rebellious Communication and Social Movements. Thousand Oaks, CA: Sage.

Entman, R. M. (1993). Framing: toward Clarification of a Fractured Paradigm. J. Commun. 43 (4), 51–58. doi:10.1111/j.1460-2466.1993.tb01304.x

Fawzi, N. (2019). Untrustworthy News and the Media as “Enemy of the People?” How a Populist Worldview Shapes Recipients' Attitudes Toward the Media. The Int. J. Press/Politics 24 (2), 146–164. doi:10.1177/1940161218811981

Fernández, R. (2020). Confianza de los españoles en los medios de comunicación a mayo de 2019. Available at: https://es.statista.com/estadisticas/538852/confianza-en-los-medios-de-comunicacion-espana/ (Accessed April 30, 2021).

Figenschou, T. U., and Ihlebæk, K. A. (2019). Challenging Journalistic Authority: Media Criticism in Far-Right Alternative Media. Journalism Studies 20 (9), 1221–1237. doi:10.1080/1461670X.2018.1500868

González-Enríquez, C. (2017). The Spanish Exception: Unemployment, Inequality and Immigration, but No Right-wing Populist Parties. WP No 3/2017. Elcano Royal. Available at: https://bit.ly/3s1KnK9 (Accessed March 3, 2021).

Haller, A., and Holt, K. (2019). Paradoxical Populism: How PEGIDA Relates to Mainstream and Alternative media. Inf. Commun. Soc. 22 (12), 1665–1680. doi:10.1080/1369118x.2018.1449882

Hallin, D. C., and Mancini, P. (2004). Comparing Media Systems: Three Models of Media and Politics. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press. doi:10.1017/cbo9780511790867

Heft, A., Mayerhöffer, E., Reinhardt, S., and Knüpfer, C. (2020). Beyond Breitbart: Comparing Right‐Wing Digital News Infrastructures in Six Western Democracies. Policy & Internet 12 (1), 20–45. doi:10.1002/poi3.219

Hernández Conde, M., and Fernández García, M. (2019). Partidos Emergentes de la Ultraderecha: ¿Fake News, Fake Outsiders? Vox y la web Caso Aislado en las Elecciones Andaluzas de 2018. Tekn 16, 33–53. doi:10.5209/TEKN.63113

Holt, K., Ustad Figenschou, T., and Frischlich, L. (2019). Key Dimensions of Alternative News Media. Digital Journalism 7 (7), 860–869.

Holtz-Bacha, C. (2020). “Putting the Screws on the Press: Populism and Freedom of the Media. Perspectives on Populism and the Media,”. Editors B. Krämer, and C. Holtz-Bacha (Baden-Baden: Nomos), 109–124. doi:10.5771/9783845297392-109

International Federation of Journalists, IFJ (2020). IFJ Global Charter of Ethics for Journalists. Available at: https://www.ifj.org/fileadmin/user_upload/Global_Charter_of_Ethics_EN.pdf (Accessed April 29, 2021).

Kim, J.-N., and Gil de Zúñiga, H. (2021). Pseudo-Information, Media, Publics, and the Failing Marketplace of Ideas: Theory. Am. Behav. Scientist. 65 (2), 163–179. doi:10.1177/0002764220950606

Krouwel, A., Kutiyski, Y., Van Prooijen, J.-W., Martinsson, J., and Markstedt, E. (2017). Does Extreme Political Ideology Predict Conspiracy Beliefs, Economic Evaluations and Political Trust? Evidence from Sweden. J. Soc. Polit. Psych. 5 (2), 435–462. doi:10.5964/jspp.v5i2.745

Makridis, C., and Rothwell, J. T. (2020). The Real Cost of Political Polarization: Evidence from the COVID-19 Pandemic. SSRN J. 34, 1–44. doi:10.2139/ssrn.3638373

Márquez, F. V. (2020). “Ecosistema De Fake News En España,” in Ética, Comunicación Y Género: Debates Actuales. Editors J. C. Suárez Villegas, and S. Marín Conejo (Madrid: Dykinson), 68–77. doi:10.2307/j.ctv153k408.9

Mourão, R. R., and Robertson, C. T. (2019). Fake News as Discursive Integration: An Analysis of Sites that Publish False, Misleading, Hyperpartisan and Sensational Information. Journalism Stud. 20 (14), 2077–2095. doi:10.1080/1461670x.2019.1566871

Mudde, C. (2004). Populist Zeitgeist. Government Opposition 39, 542–563. doi:10.1111/j.1477-7053.2004.00135.x

Müller, P., and Schulz, A. (2021). Alternative Media for a Populist Audience? Exploring Political and Media Use Predictors of Exposure to Breitbart, Sputnik, and Co. Inf. Commun. Soc. 24 (2), 277–293. doi:10.1080/1369118x.2019.1646778

Munger, K. (2020). All the News That's Fit to Click: The Economics of Clickbait Media. Polit. Commun. 37 (3), 376–397. doi:10.1080/10584609.2019.1687626

Newman, N., Fletcher, R., Kalogeropoulos, A., Levy, D. A., and Nielsen, R. K. (2019). Digital News Report 2019. Oxford: Reuters Institute. doi:10.1287/52ec34df-5527-47cb-8fec-2a3d63fba96d

Nguyen, A., and Catalan-Matamoros, D. (2020). Digital Mis/disinformation and Public Engagement with Health and Science Controversies: Fresh Perspectives from Covid-19. Media Commun. 8 (2), 323–328. doi:10.17645/mac.v8i2.3352

Palau-Sampio, D. (2016). Reference Press Metamorphosis in the Digital Context: Clickbait and Tabloid Strategies in Elpais.Com. Commun. Soc. 29 (2), 63–79. doi:10.15581/003.29.2.63-79

Rae, M. (2020). Hyperpartisan News: Rethinking the media for Populist Politics. New Media & Society. doi:10.1177/1461444820910416

Ramírez, V., and Castellón, J. (2018). Caso Aislado', el fabricante español de 'fake news' vinculado a VOX. La Sexta, 9 Octuber. Available at: https://bit.ly/38ZXNyU https://bit.ly/38ZXNyU (Accessed March 6, 2021).

Rathnayake, C. (2018). Conceptualizing Satirical Fakes as a New media Genre: An Attempt to legitimize'post-truth Journalism' [Conference Presentation]. The Internet, Policy & Politics Conference 2018. UK: University of OxfordAvailable at: https://bit.ly/2Qs6lIy (Accessed March 4, 2021).

Rauch, J. (2015). Exploring the Alternative-Mainstream Dialectic: What “Alternative Media” Means to a Hybrid Audience. Commun. Cult. Critique 8 (1), 124–143. doi:10.1111/cccr.12068

Rodríguez, C. (2001). Fissures in the Mediascape: An International Study of Citizens’ media. Cresskill, NJ: Hampton Press.

Romer, D., and Jamieson, K. H. (2020). Conspiracy Theories as Barriers to Controlling the Spread of COVID-19 in the U.S. Soc. Sci. Med. 263, 113356. doi:10.1016/j.socscimed.2020.113356

Rone, J. (2020). Far Right Alternative News media as ‘indignation Mobilization Mechanisms’: How the Far Right Opposed the Global Compact for Migration. Information, Communication & Society, 1–18. doi:10.1080/1369118X.2020.18640

Sánchez Castrillo, Á. (2021). Alerta Digital, la fábrica de noticias falsas del exjefe de prensa de Jesús Gil y algunos curas franquistas que pide cerrar la Fiscalía. Infolibre, 4 March. Available at: https://bit.ly/3tJBbKU (Accessed March 8, 2021).

Scheufele, D. A. (1999). Framing as a Theory of Media Effects. J. Commun. 49, 103–122. doi:10.1111/j.1460-2466.1999.tb02784.x

Schulz, A., Müller, P., Schemer, C., Wirz, D. S., Wettstein, M., and Wirth, W. (2018). Measuring Populist Attitudes on Three Dimensions. Int. J. Public Opin. Res. 30 (2), 316–326. doi:10.1093/ijpor/edw037

Schulze, H. (2020). Who Uses Right-Wing Alternative Online Media? an Exploration of Audience Characteristics. Politics and Governance 8 (3), 6–18. doi:10.17645/pag.v8i3.2925

Spanish Ministry of Health (2020). Covid -19 Pandemic Evolution. Available at: https://cnecovid.isciii.es/covid19/#ccaa (Accessed March 15, 2021).

Stroud, N. J. (2010). Polarization and Partisan Selective Exposure. J. Commun. 60 (3), 556–576. doi:10.1111/j.1460-2466.2010.01497.x

Tankard, J. W. (2001). “An Empirical Approach to the Study of Media Framing,” in Framing Public Life: Perspectives of Media and Our Understanding of the Social World. Editor S. D. Reese (Mahwah, NJ: Erlbaum).

Van Prooijen, J.-W., Krouwel, A. P. M., and Pollet, T. V. (2015). Political Extremism Predicts Belief in Conspiracy Theories. Soc. Psychol. Personal. Sci. 6 (5), 570–578. doi:10.1177/1948550614567356

Vila Márquez, F. (2020). Ecosistema de Fake News en España: Una Aproximación al Análisis de los Portales de Noticias Falsas y su Implicación en la Creación de Opinión Pública. Ética, Comunicación y Género: Debates Actuales in Suárez Villegas, J. C., and Marín Conejo, S. Madrid: Dykinson (5), 68–77.

Waisbord, S. (2018). The Elective Affinity between post-truth Communication and Populist Politics. Commun. Res. Pract. 4 (1), 17–34. doi:10.1080/22041451.2018.1428928

Wasilewski, K. (2019). US Alt-Right media and the Creation of the Counter-collective Memory. J. Altern. Community Media 4 (1), 77–91. doi:10.1386/joacm_00044_1

Wells, C., Shah, D., Lukito, J., Pelled, A., Pevehouse, J. C., and Yang, J. (2020). Trump, Twitter, and News media Responsiveness: A media Systems Approach. New Media Soc. 22 (4), 659–682. doi:10.1177/1461444819893987

Wirz, D. (2018). Persuasion through Emotion? an Experimental Test of the Emotion-Eliciting Nature of Populist Communication. Int. J. Commun. 12, 1114–1138.

Keywords: hyper-partisan media, polarization, pandemic skepticism, COVID-19, right-wing ideology, populism, Spain, pseudo-media

Citation: Palau-Sampio D (2021) Pseudo-Media Sites, Polarization, and Pandemic Skepticism in Spain. Front. Polit. Sci. 3:685295. doi: 10.3389/fpos.2021.685295

Received: 24 March 2021; Accepted: 30 June 2021;

Published: 21 July 2021.

Edited by:

Anna Herranz-Surrallés, Maastricht University, NetherlandsReviewed by:

Jose Javier Olivas Osuna, National University of Distance Education (UNED), SpainLesley-Ann Daniels, Institut Barcelona d’Estudis Internacionals, Spain

Copyright © 2021 Palau-Sampio. This is an open-access article distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution License (CC BY). The use, distribution or reproduction in other forums is permitted, provided the original author(s) and the copyright owner(s) are credited and that the original publication in this journal is cited, in accordance with accepted academic practice. No use, distribution or reproduction is permitted which does not comply with these terms.

*Correspondence: Dolors Palau-Sampio, dolors.palau@uv.es

Dolors Palau-Sampio

Dolors Palau-Sampio