Barriers and facilitators to interhospital transfer of acute pulmonary embolism: An inductive qualitative analysis

- 1Department of Medicine, University of Pittsburgh, Pittsburgh, PA, United States

- 2Department of Medicine, Temple University, Philadelphia, PA, United States

- 3Department of Medicine, Emory University, Atlanta, GA, United States

- 4Massachusetts General Hospital and Harvard Medical School, Boston, MA, United States

- 5Abbott Northwestern Hospital, Minneapolis, MN, United States

- 6Cedars-Sinai Medical Center, Los Angeles, CA, United States

- 7College of Medicine, University of Cincinnati, Cincinnati, OH, United States

- 8School of Medicine, University of California San Francisco, San Francisco, CA, United States

- 9Houston Methodist Hospital, Houston, TX, United States

- 10A. Cardarelli Hospital, Naples, Italy

- 11Baystate Medical Center, University of Massachusetts Baystate, Springfield, MA, United States

- 12Piedmont Atlanta Hospital, Atlanta, GA, United States

Background: Interhospital transfer (IHT) of patients with acute life-threatening pulmonary embolism (PE) is necessary to facilitate specialized care and access to advanced therapies. Our goal was to understand what barriers and facilitators may exist during this transfer process from the perspective of both receiving and referring physicians.

Methods: This qualitative descriptive study explored physician experience taking care of patients with life threatening PE. Subject matter expert physicians across several different specialties from academic and community United States hospitals participated in qualitative semi-structured interviews. Interview transcripts were subsequently analyzed using inductive qualitative description approach.

Results: Four major themes were identified as barriers that impede IHT among patients with life threatening PE. Inefficient communication which mainly pertained to difficulty when multiple points of contact were required to complete a transfer. Subjectivity in the indication for transfer which highlighted the importance of physicians understanding how to use standardized risk stratification tools and to properly triage these patients. Delays in data acquisition were identified in regards to both obtaining clinical information and imaging in a timely fashion. Operation barriers which included difficulty finding available beds for transfer and poor weather conditions inhibiting transportation. In contrast, two main facilitators to transfer were identified: good communication and reliance on colleagues and dedicated team for transferring and treating PE patients.

Conclusion: The most prominent themes identified as barriers to IHT for patients with acute life-threatening PE were: (1) inefficient communication, (2) subjectivity in the indication for transfer, (3) delays in data acquisition (imaging or clinical), and (4) operational barriers. Themes identified as facilitators that enable the transfer of patients were: (1) good communication and (2) a dedicated transfer team. The themes presented in our study are useful in identifying opportunities to optimize the IHT of patients with acute PE and improve patient care. These opportunities include instituting educational programs, streamlining the transfer process, and formulating a consensus statement to serve as a guideline regarding IHT of patients with acute PE.

Introduction

Acute pulmonary embolism (PE) is the third leading cause of cardiovascular death in the United States (1, 2). Timely triage, diagnosis, risk stratification and treatment of an acute PE are critical. With recent advances, the treatment of acute PE has become complex, ranging from anticoagulation alone to catheter-based interventions, and surgical thrombectomy with mechanical support (3–5). Given the breadth of advanced therapies available, in certain settings, patients may require interhospital transfer (IHT) to a tertiary care facility to have access to multidisciplinary pulmonary embolism response teams (PERT) (6).

The most recent European Guidelines for management of acute PE recognize the value of PERTs in the management of intermediate and high-risk PE patients (4). In some centers, PERT implementation has led to increased number of advanced therapies, without an increase in major bleeding (7). Additionally, numerous studies have demonstrated that having a PERT decreases length of stay, costs and even mortality (8–13).

Transferring patients between institutions, to facilitate advanced care may be necessary to achieve optimal clinical outcomes and salvage of life, but it also represents a period of heightened vulnerability for patients as well as physicians responsible for their care. IHT has been extensively studied, for numerous acute medical conditions such as trauma, acute ST-elevation myocardial infarction and stroke (14–16). However, the process of IHT for PE is less well understood. The aim of this study was to investigate barriers and facilitators of transferring patients with acute PE amongst physicians who are responsible for both the transferring and receiving of patients, with the eventual goal of learning how to better streamline the process and improve patient safety.

Methods

A writing group was established by members of the Clinical Protocols Committee of the PERT Consortium™. This study was approved by the University of Pittsburgh Institutional Review Board (Study #20070380). The consolidated criteria for reporting qualitative studies (COREQ) guidelines was reviewed and adhered to, where applicable (17).

Recruitment

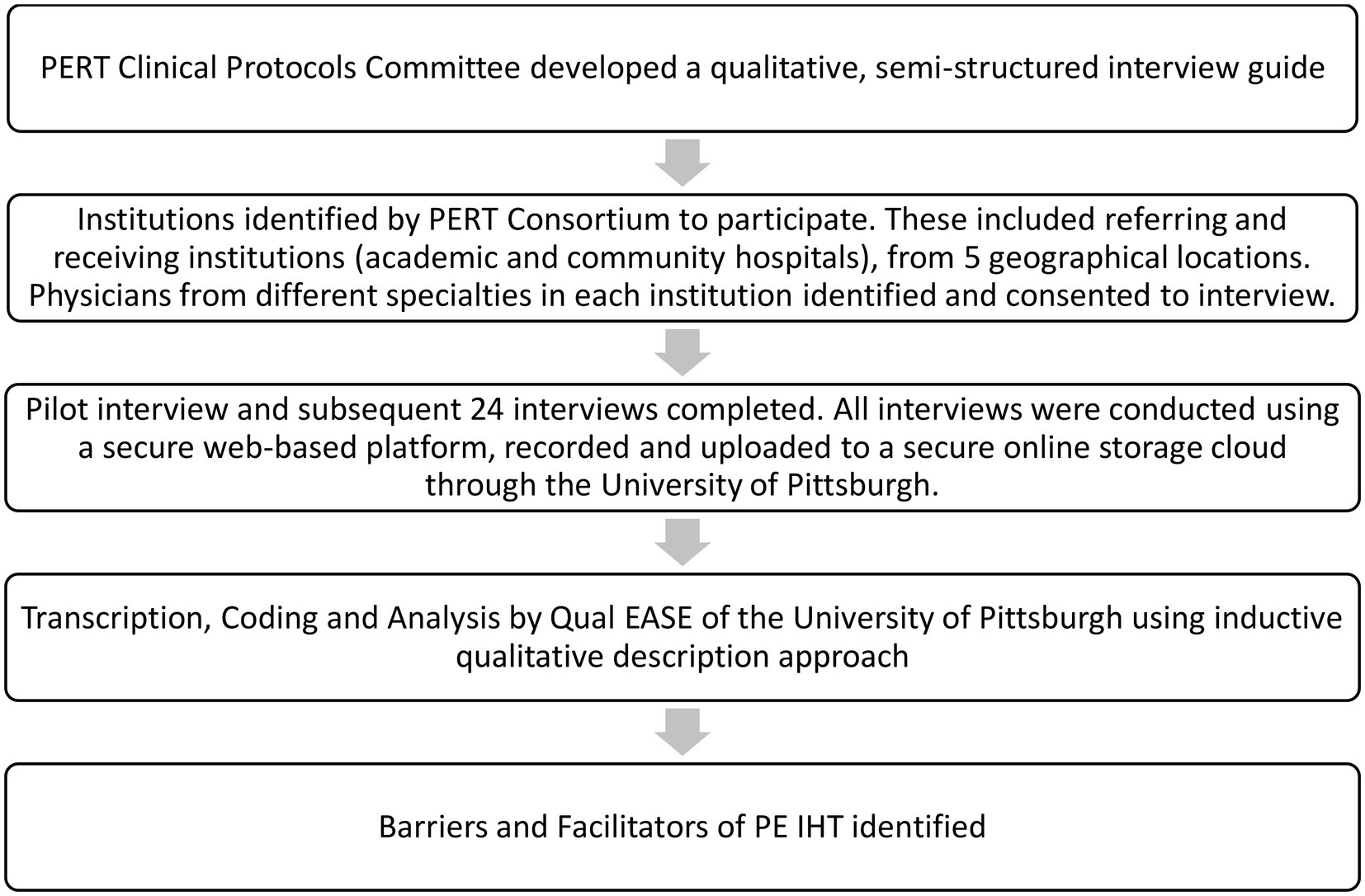

Twenty-nine subject matter expert physicians who typically refer (“referring physicians”) and physicians who typically receive (“receiving physicians”) PE patients were identified by members from the Clinical Protocols Committee of the PERT Consortium™ (Figure 1). Twenty-five of the identified expert physicians participated in the study, while four of the physicians were omitted because there was no email correspondence back from them. The physicians who were recruited and interviewed were colleagues of members of The PERT Consortium™, but not active members. Consortium members were asked to identify participants from different specialists (pulmonary, critical care, anesthesiology, and emergency medicine), different types of hospitals (academic and community) and different geographic areas in the United States. An invitation letter was sent to each physician via email that explained the goal of the study and included the study consent form. Twenty-four of the participants were provided a $250 honorarium to compensate them for their time, while one participant declined the honorarium citing that it could be seen as a conflict of interest. Funding was provided by a grant from the Boston Scientific Corporation to the PERT Consortium™.

Figure 1. Methods flow chart. PERT, pulmonary embolism response team. Qual EASE, qualitative, evaluation, and stakeholder engagement research core of the Center for Research on Healthcare’s Data Center at the University of Pittsburgh. IHT, interhospital transfer. PE, pulmonary embolism.

Interviews

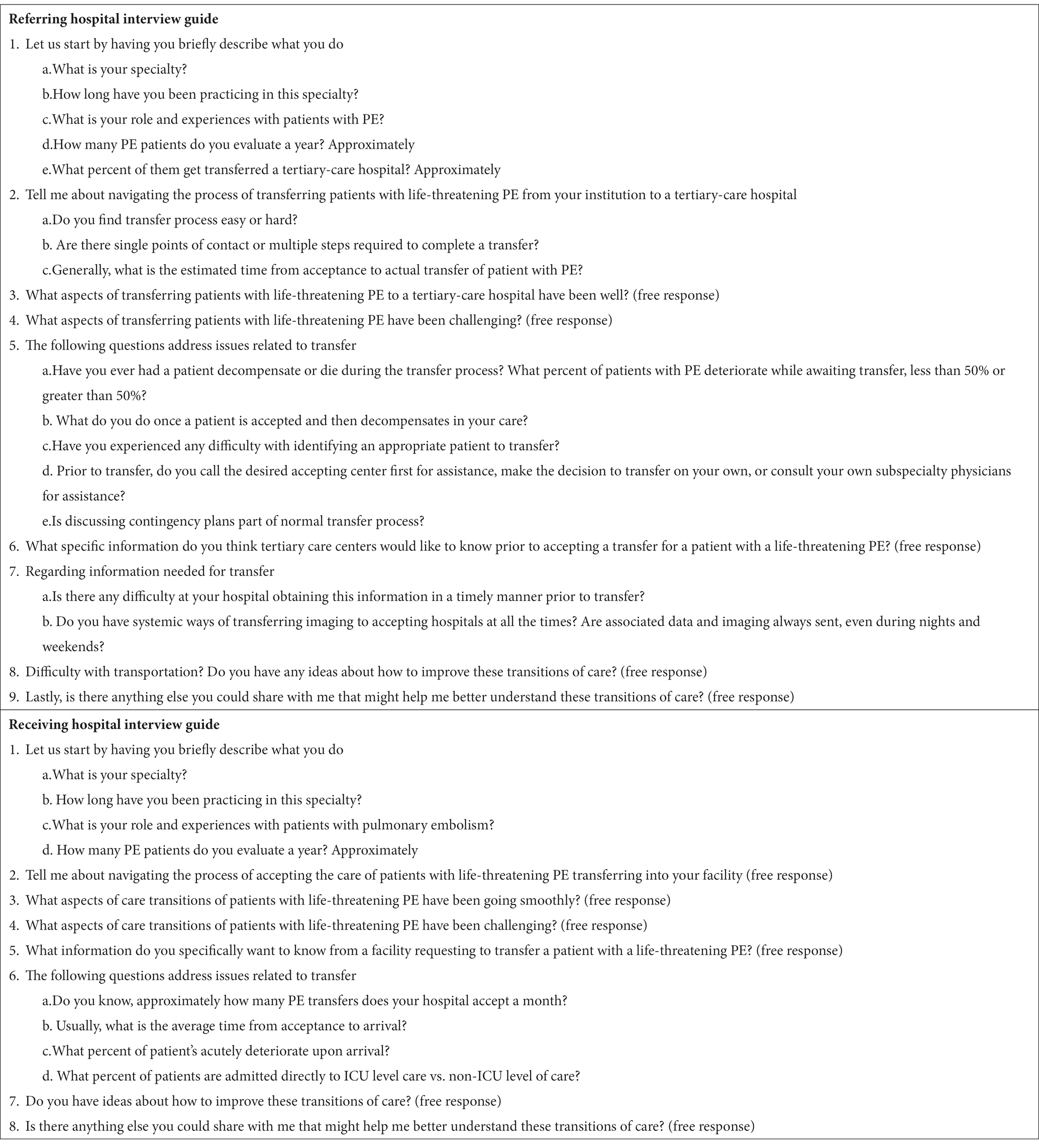

A semi-structured interview guide was created by members of the Clinical Protocols Committee of The PERT Consortium™ for the referring physicians and for the receiving physicians (Table 1). It included questions on the process of transferring or receiving patients with life threatening PE, its barriers, and facilitators. Most questions had an open answer. Seven iterations were revised before the final interview guide was agreed upon.

A pilot interview was conducted by a study investigator (JD), a male internal medicine physician. JD was familiar with basic interview techniques, but did not have formal training with semi-structured interviews. The pilot interview was completed with one receiving physician, and reviewed by another study investigator (BRL) who is a female pulmonary and critical physician, to ensure all questions were easily understood and relevant. After the pilot interview, no additional changes were made to the study questions. All interviews were conducted remotely with video interface by JD using a secure web-based platform and were recorded with password protection. Once completed, the interviews were uploaded to a secure online storage service through the University of Pittsburgh. The interviewer, JD, had no prior relationships with the physicians that were interviewed.

Data collection and analysis

The interviews were evaluated by the Qualitative, Evaluation, and Stakeholder Engagement Research Core of the Center for Research on Healthcare’s Data Center at the University of Pittsburgh (Qual EASE) for analysis. All audio files were transcribed verbatim with identifying details redacted.

Analysis followed an inductive qualitative description approach (18, 19), a common qualitative approach in medical studies, in which the analysts focused on describing the viewpoints of the interviewees as closely as possible without abstracting to the level of social theory. Interview analysis was completed by a team of trained qualitative analysts at the Qual EASE within the University of Pittsburgh. An experienced Qual EASE analyst created a codebook inductively from the content of the interviews and categorized participant responses to “barriers” or “facilitators” of PE patient care during the IHT process. This analyst and a second analyst then practiced using the codebook on 4 transcripts, meeting afterwards to adjudicate coding and refine the codebook as necessary. Subsequently, they then independently coded 10 transcripts for the purposes of measuring intercoder reliability using Cohen’s kappa scores for each code in the codebook. The average kappa score was 0.75, indicating substantial agreement (20). The two coders adjudicated all coding disagreements to full agreement, and then the primary coder coded the remaining transcripts independently. The resulting coding was used to conduct both conventional content (21) and thematic (22, 23) analyses of the results. The content analysis summarized was discussed in the interviews and served as step one of the six-phase guide to thematic analysis by Braun and Clarke (14), which was followed in order to conduct a thematic analysis: (1) familiarization with data, (2) generation of initial code, (3) search for themes, (4) review of themes, (5) definition and names of themes, and (6) production of the report. Final analysis consisted of sorting coded barriers and facilitators to transfer in the text into themes, which were then shared with the broader study team for corroboration by the interviewer, and to allow the study team to give the coders and analysts feedback that helped to better flesh out resulting themes.

Results

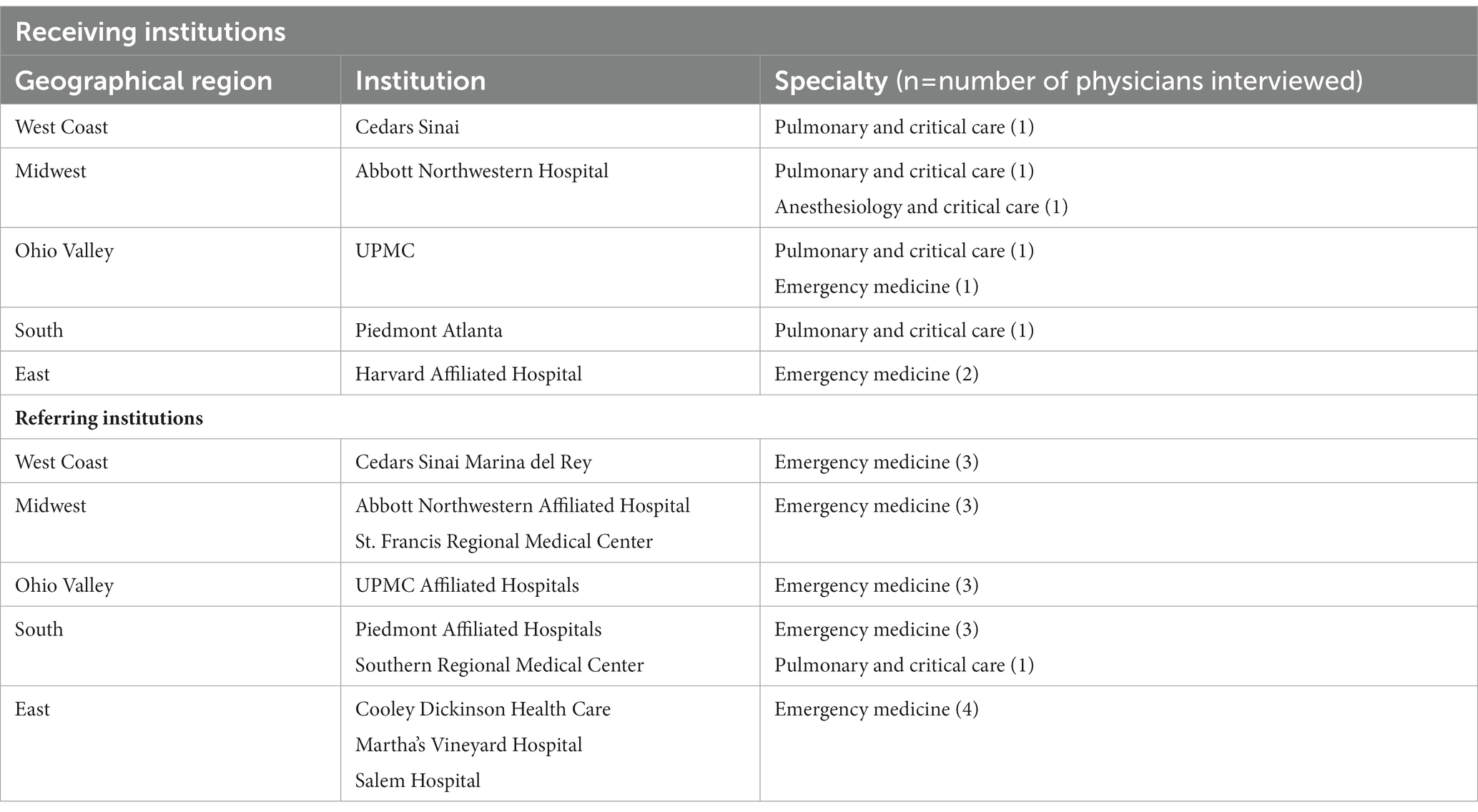

Twenty-five interviews were conducted between September 21, 2020 and December 11, 2020 (Table 2). Themes are described in depth below, with supporting quotes presented both in-text and in Table 3. Quotes in the table are cited with a quote number, (e.g., Quote 1).

Table 2. Referring and receiving institutions and specialties that participated in semi-structured interviews.

Table 3. Quotes representing barriers and facilitators to interhospital transfer of pulmonary embolism (PE) patients.

Barriers to interhospital transfer of pulmonary embolism patients

Several barriers to a smooth transfer process for PE patients were identified. Barriers to transfer process include: (1) inefficient communication, (2) subjectivity in the indication for transfer, (3) delays in data acquisition (imaging or clinical), and (4) operational barriers, including lack of available beds and poor weather conditions inhibiting transportation, and patient desires and/or informed decision making, to avoid transfer for personal or financial reasons.

Inefficient communication

Inefficient communication among physicians causes perceived delays transferring PE patients. For initiating transfers, referring physicians struggle in their efforts to make initial contact with receiving centers. Having no single point of contact may cause time delays (Quote 1). For referring physicians not part of a larger network, it can take multiple phone calls to different facilities to find one that will accept a transfer. Furthermore, lack of centralized call systems was reported as a contributor to physicians not being able to efficiently initiate a transfer.

Physicians also reported challenges when they do not share the same medical record system, radiology images or patient data. The inability to share images and data in real time delays care. Although images can be sent with the patient on a disk, this approach still represents a delay for accepting physicians. The more information receiving physicians have prior to patient arrival, the sooner they can prepare for the patient. Also, receiving physicians can make better clinical judgments when they can evaluate all the patient’s data while talking on the phone with the referring physician (Quote 2).

Subjectivity in the indication for transfer

The subjectivity involved in identifying and triaging PE patients between referring and receiving physicians creates challenges on both ends, in that physicians can struggle to decide if a patient needs to be transferred. Participants report that it is not always clear which patients need to be transferred. This lack of clarity can lead to disagreements amongst physicians. For example, a referring physician may risk stratify a patient using imaging alone but receiving physicians might refer to imaging and biomarkers or other test results that the referring physician may not have access to or may not routinely use in their clinical practice (Quote 3). Referring physicians find it frustrating when they want to transfer a patient and the transfer is not approved by the accepting facility (Quote 4).

The referring physician may feel that their center lacks the proper treatment, level of care or expertise for the patient, or may personally feel uncomfortable starting treatments beyond anticoagulation alone. “It’s hard to make that decision to [either use heparin or tissue plasminogen activator (tPA) and then start heparin after the tPA after an undisclosed period of time.” [Emergency medicine (EM) physician 1] Sometimes referring physicians are not comfortable administering tPA and will transfer a patient without doing so. This deferment can delay patient care and affect patient outcomes.

Additionally, managing patients that decompensate prior to or during transfer is a challenge. Referring physicians may not adequately stabilize a patient prior to transfer or the transport team may need to manage decompensating patients in route. Additionally, waiting for the appropriate emergency medical service crew (ground or air, personnel, equipment and monitoring required during transfer, etc.) to transfer PE patients may cause delays in patients receiving the care they need. Patients who are too unstable also might not qualify for transfer.

Delays in data acquisition

Referring physicians described difficulty reaching other individuals needed to perform imaging, particularly off-hours (Quote 5). Delays in imaging result in delays in patient care (Quote 6). High patient volume can also cause delays in obtaining imaging (Quote 7).

Furthermore, delays may be caused by lack of understanding of the urgency of the situation by those involved in imaging. Referring physicians found a lack of urgency from radiologists and computed tomography (CT) technicians. Radiologists want documentation of the medical risks, such as acute kidney injury patients may experience, before approving scans (Quote 8). On the receiving end, physicians encounter a lack of urgency from providers for hemodynamically unstable PE patients. It is “frustrating from an emergency medicine perspective” [EM 2] that these patients must wait to be triaged before they are evaluated by a PE consultant.

Operational barriers

Several structural and situational barriers interfere with the transfer process. A lack of bed availability impacts both accepting and referring physicians. If the referring physician’s facility does not have an open bed for a PE patient, they must transfer that patient. Receiving facilities are not able to accept patients if there are no beds available in their institution and may subsequently, deny a transfer based on this circumstance alone (Quote 9).

Further delays can come from poor weather for transport, which can prevent helicopters from flying. Moreover, poor weather conditions particularly impact hospitals in unique locations, such as islands or remote locations, in that both ground and air transportation may be hindered (Quote 10).

Additionally, physicians encounter barriers to transfer from their patients. Patients worry about staying local and close to their families as well as covering the cost of transfer. These concerns need to be mediated by the referring physician before they initiate transfer. The time it takes to assure patients that transferring them is best for their care can cause significant delays, during which time they may not be getting the necessary care they need. Further, getting the patient’s insurance to authorize and cover the cost for the transfer and higher level of care may delay the patients’ getting to the accepting site (Quotes 11 and 12).

Facilitators to interhospital transfer of pulmonary embolism patients

Facilitators of the transfer process are often the inverse of the barriers. Two main facilitators to transfer were identified: (1) Good communication and reliance on colleagues and, (2) The use of a dedicated team for transferring and treating PE patients (i.e., PERT) helps facilitate better communication between physicians and identify appropriate patients for transfer. Each of these will be discussed in turn.

Good communication and reliance on colleagues

Physicians find that centralized call centers are useful in facilitating transfers, because centralized call centers provide a single point of contact at receiving facilities with staff available at all times to quickly discuss and initiate a transfer. As one participant put it: “So, for PE, [PERT] is generally one-stop shopping.” [EM 3] A centralized call center is “much more streamlined” [EM 4] than having to call multiple facilities to find one that will receive a transfer.

Additionally, sharing a medical record system is “seamless in terms of the continuity. All our notes, labs, x-rays, everything is available to that institution.” [EM 5] Physicians are able to access patient information while on the phone with the referring physician and communicate in real time what the treatment plan would be. Receiving physicians also can view patient data prior to the patient’s arrival to determine and coordinate the treatment plan before the patient arrives. This is particularly useful for those patients in whom a catheter-based or surgical intervention is anticipated.

Physicians also praised the personnel support they received during the transfer process. Pharmacists in the referring emergency department help initiate necessary medications (Quote 13). Transport teams were praised for their quick response times and the care they provide patients in route (Quote 14).

Dedicated transfer and treatment teams (i.e., pulmonary embolism response teams)

PERT was praised as helping to facilitate the transfer process. Participants describe that PERT defines clear treatment protocols that identify massive (or high risk) versus submassive (or intermediate risk) PE. These protocols help physicians determine where patients go once transferred, e.g., the intensive care unit or a lower level of care, and if advanced therapies are indicated. This accessibility allows physicians who are unsure what to do with a patient to consult PERT for next steps (Quote 15).

Discussion

The transfer of critically ill patients can be complex but is often necessary. To our knowledge, this is the first qualitative study to examine the perceived barriers of IHT in patients with an acute PE. Previous qualitative research has examined barriers and perceived risk related to IHT for patients with life threatening medical condition other than PE. Overarching themes identified included inadequate communication, gaps in clinical practice, and lack of structure guiding the IHT process as barriers to care. Other studies have identified transfer delays, failure to transmit records, and setting unrealistic expectations as threats to the safety of patients requiring IHT (24).

In a recent review (6), our group described topics that should be included in the discussions between transferring and receiving physicians. Topics included patient presentation, current hemodynamic status, anticoagulation, relevant medical history, code status, laboratory and imaging results, and contingencies for management in case of deterioration. Many of these topics were evident in the interviews conducted for the current study. Education for transferring physicians on an “optimal transfer process” including items such as “checklists for discussion” may smooth the transfer process and represents another opportunity in our ongoing work to further improve this process.

Studies demonstrate that patients have improved 30 day survival when transferred to a high volume center with physicians who are more experienced with treating acute PE (25). Thus, it is important that the IHT process be as seamless as possible.

It appears that lack of communication can be generalized across all four barriers identified in the transfer process. Inefficient communication may include poor physician-to-physician communication, poor communication with call centers, and lack of access to electronic medical records (EMR), all of which hinder IHT. Lack of access to medical information presents a difficult challenge when an accepting physician is faced with the decision to accept a patient with an acute PE, particularly without being able to review relevant imaging and laboratory studies. Importantly, communication barriers also exist among patients and physicians which may be exacerbated when patients sometimes are resistant to the idea of transfer for reasons such as cost or distance from their home or family members.

In contrast, facilitators to IHT identified from our interviews translate to utilizing a central transfer center, discussing the case with a dedicated PERT member, and sharing the electronic medical record system. All of these factors, facilitate communication, and expedite the transfer process with the intent of improving patient care.

Limitations

While a potential limitation to this study is the number of interviews conducted (25), physicians from different geographical locations and specialties across the United States were recruited, which diversified our understanding of the processes of transfer, EMRs, and patient population. Another limitation is that the physicians interviewed were either from institutions with a PERT (“receiving physicians”) or referring to an institution with a PERT (“accepting physicians”), their experiences with managing acute PE may not be representative of all providers. A single pilot interview was performed; however, no changes were deemed necessary after this pilot interview, and the subsequent interviews that were conducted yielded consistent codable data. Lastly, while we identified these broad themes related to barriers and facilitators to IHT, they may not all pertain to all hospital systems. It should be noted that having a clear understanding of a specific hospital system is needed prior to considering which barrier or facilitator is relevant.

Conclusion

By identifying these broad themes, the current study can be used for process improvement and should stimulate further investigation into the safety of patient transfers. These activities may include educational programs for transferring facilities on risk stratification and indications for advanced therapies, which may then help identify which patients are most appropriate for transfer. Furthermore, the development of a checklist to standardize the course of transferring and receiving acute PE patients may help assure adequate information is readily available to the receiving institution, similar the one already developed by The PERT Consortium™ (6). Ultimately, formulating consensus and best practices to serve as a guideline in IHT may improve the care of patients with life-threatening acute PE.

Data availability statement

The raw data supporting the conclusions of this article will be made available by the authors, without undue reservation.

Ethics statement

The studies involving human participants were reviewed and approved by University of Pittsburgh Institutional Review Board (Study #20070380). The patients/participants provided their written informed consent to participate in this study.

Author contributions

JD, BR-L, CK, PR, MM, RR, RM, OF, MH, AK, and CR were responsible for content development. JD, BR-L, CK, PR, MM, RR, RM, MH, AK, and CR wrote the first draft. JE, VB, SS, EB, MF, JD, BR-L, CK, PR, MM, RR, RM, OF, MH, AK, and CR contributed to concept, critical revision, and final approval of the manuscript. All authors contributed to the article and approved the submitted version.

Funding

Funding was provided by a grant from the Boston Scientific Corporation to the PERT Consortium™.

Conflict of interest

CK is consultant for BMS and Abbott, and provided by a grant from Grifols and Diagnostica Stago. RR is consultant for Abbott, BMS, Dova, Janseen, Inari Medical, and Penumbra, and provided by a grant from Janssen and BMS. OF is consultant for Inari Medical. BR-L is consultant for Inari Medical and Johnson & Johnson, and provided by a grant from Johnson & Johnson.

The remaining authors declare that the research was conducted in the absence of any commercial or financial relationships that could be construed as a potential conflict of interest.

Publisher’s note

All claims expressed in this article are solely those of the authors and do not necessarily represent those of their affiliated organizations, or those of the publisher, the editors and the reviewers. Any product that may be evaluated in this article, or claim that may be made by its manufacturer, is not guaranteed or endorsed by the publisher.

References

1. MMWR. Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC). Venous thromboembolism in adult hospitalizations–United States, 2007–2009. Morb Mortal Wkly Rep. (2012) 61:401–4.

2. Martin, KA, Molsberry, R, Cuttica, MJ, Desai, KR, Schimmel, DR, and Khan, SS. Time trends in pulmonary embolism mortality rates in the United States, 1999 to 2018. J Am Heart Assoc. (2020) 9:e016784. doi: 10.1161/JAHA.120.016784

3. Rivera-Lebron, B, McDaniel, M, Ahrar, K, Alrifai, A, Dudzinski, DM, Fanola, C, et al. Diagnosis, treatment and follow up of acute pulmonary embolism: consensus practice from the PERT consortium. Clin Appl Thromb Off J Int Acad Clin Appl Thromb. (2019) 25:3037. doi: 10.1177/1076029619853037

4. Konstantinides, SV, Meyer, G, Becattini, C, Bueno, H, Geersing, GJ, Harjola, VP, et al. 2019 ESC guidelines for the diagnosis and management of acute pulmonary embolism developed in collaboration with the European Respiratory Society (ERS). Eur Heart J. (2020) 41:543–603. doi: 10.1093/eurheartj/ehz405

5. Stevens, SM, Woller, SC, Kreuziger, LB, Bounameaux, H, Doerschug, K, Geersing, GJ, et al. Antithrombotic therapy for VTE disease: second update of the CHEST guideline and expert panel report. Chest. (2021) 160:e545–608. doi: 10.1016/j.chest.2021.07.055

6. Rali, P, Sacher, D, Rivera-Lebron, B, Rosovsky, R, Elwing, JM, Berkowitz, J, et al. Interhospital transfer of patients with acute pulmonary embolism: challenges and opportunities. Chest. (2021) 160:1844–52. doi: 10.1016/j.chest.2021.07.013

7. Rosovsky, R, Chang, Y, Rosenfield, K, Channick, R, Jaff, MR, Weinberg, I, et al. Changes in treatment and outcomes after creation of a pulmonary embolism response team ( PERT ), a 10-year analysis. J Thromb Thrombolysis. (2019) 47:31–40. doi: 10.1007/s11239-018-1737-8

8. Fleitas Sosa, D, Lehr, AL, Zhao, H, Roth, S, Lakhther, V, Bashir, R, et al. Impact of pulmonary embolism response teams on acute pulmonary embolism: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Eur Respir Rev an Off J Eur Respir Soc. (2022) 31:220023. doi: 10.1183/16000617.0023-2022

9. Wright, C, Goldenberg, I, Schleede, S, McNitt, S, Gosev, I, Elbadawi, A, et al. Effect of a multidisciplinary pulmonary embolism response team on patient mortality. Am J Cardiol. (2021) 161:102–7. doi: 10.1016/j.amjcard.2021.08.066.

10. Chaudhury, P, Gadre, SK, Schneider, E, Renapurkar, RD, Gomes, M, Haddadin, I, et al. Impact of multidisciplinary pulmonary embolism response team availability on management and outcomes. Am J Cardiol. (2019) 124:1465–9. doi: 10.1016/j.amjcard.2019.07.043

11. Annabathula, R, Dugan, A, Bhalla, V, Davis, GA, Smyth, SS, and Gupta, VA. Value-based assessment of implementing a pulmonary embolism response team (PERT). J Thromb Thrombolysis. (2021) 51:217–25. doi: 10.1007/s11239-020-02188-3

12. Myc, LA, Solanki, JN, Barros, AJ, Nuradin, N, Nevulis, MG, Earasi, K, et al. Adoption of a dedicated multidisciplinary team is associated with improved survival in acute pulmonary embolism. Respir Res. (2020) 21:159. doi: 10.1186/s12931-020-01422-z

13. Porres-Aguilar, M, Rosovsky, RP, Rivera-Lebron, BN, Kaatz, S, Mukherjee, D, Anaya-Ayala, JE, et al. Pulmonary embolism response teams: changing the paradigm in the care for acute pulmonary embolism. J Thromb Haemost. (2022) 20:2457–64. doi: 10.1111/jth.15832

14. Viel, IL, Moura, BRS, Martuchi, SD, and de Souza, NL. Factors associated with interhospital transfer of trauma victims. J Trauma Nurs. (2019) 26:257–62. doi: 10.1097/JTN.0000000000000452

15. Burstein, B, Bibas, L, Rayner-Hartley, E, Jentzer, JC, van Diepen, S, and Goldfarb, M. National Interhospital Transfer for patients with acute cardiovascular conditions. CJC open. (2020) 2:539–46. doi: 10.1016/j.cjco.2020.07.003

16. Finn, EB, Campbell Britton, MJ, Rosenberg, AP, Sather, JE, Marcolini, EG, Feder, SL, et al. A qualitative study of risks related to interhospital transfer of patients with non-traumatic intracranial hemorrhage. J Stroke Cerebrovasc Dis. (2019) 28:1759–66. doi: 10.1016/j.jstrokecerebrovasdis.2018.12.048

17. Tong, A, Sainsbury, P, and Craig, J. Consolidated criteria for reporting qualitative research (COREQ): a 32-item checklist for interviews and focus groups. Int J Qual Heal care J Int Soc Qual Heal Care. (2007) 19:349–57. doi: 10.1093/intqhc/mzm042

18. Sandelowski, M. Whatever happened to qualitative description? Res Nurs Health. (2000) 23:334–40. doi: 10.1002/1098-240x(200008)23:4<334::aid-nur9>3.0.co;2-g

19. Kim, H, Sefcik, JS, and Bradway, C. Characteristics of qualitative descriptive studies: a systematic review. Res Nurs Health. (2017) 40:23–42. doi: 10.1002/nur.21768

20. McHugh, ML. Inter-rater reliability: the kappa statistic. Biochem Med. (2012) 22:276–82. doi: 10.11613/BM.2012.031

21. Hsieh, H-F, and Shannon, SE. Three approaches to qualitative content analysis. Qual Health Res. (2005) 15:1277–88. doi: 10.1177/1049732305276687

22. Braun, V, and Clarke, V. Using thematic analysis in psychology. Qual Res Psychol. (2006) 3:77–101. doi: 10.1191/1478088706qp063oa

23. Guest, G, MacQueen, K, and Namey, E. Applied thematic analysis. SAGE Publications, Inc., (2012) doi: 10.4135/9781483384436

24. Mueller, SK, and Schnipper, JL. Physician perspectives on interhospital transfers. J Patient Saf. (2019) 15:86–9. doi: 10.1097/PTS.0000000000000312

Keywords: pulmonary embolism, interhospital transfer, pulmonary embolism response team, catheter–directed thrombolysis, surgical embolectomy

Citation: DeBerry J, Rali P, McDaniel M, Kabrhel C, Rosovsky R, Melamed R, Friedman O, Elwing JM, Balasubramanian V, Sahay S, Bossone E, Farmer MJS, Klein AJP, Hamm ME, Ross CB and Rivera-Lebron BN (2023) Barriers and facilitators to interhospital transfer of acute pulmonary embolism: An inductive qualitative analysis. Front. Med. 10:1080342. doi: 10.3389/fmed.2023.1080342

Edited by:

Carlos Jerjes-Sanchez, Escuela de Medicina y Ciencias de la Salud TecSalud del Tecnológico de Monterrey, MexicoReviewed by:

Héctor David Meza-Comparán, Instituto Nacional de Geriatría, MexicoVedant Arun Gupta, University of Kentucky, United States

Copyright © 2023 DeBerry, Rali, McDaniel, Kabrhel, Rosovsky, Melamed, Friedman, Elwing, Balasubramanian, Sahay, Bossone, Farmer, Klein, Hamm, Ross and Rivera-Lebron. This is an open-access article distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution License (CC BY). The use, distribution or reproduction in other forums is permitted, provided the original author(s) and the copyright owner(s) are credited and that the original publication in this journal is cited, in accordance with accepted academic practice. No use, distribution or reproduction is permitted which does not comply with these terms.

*Correspondence: Belinda N. Rivera-Lebron, riveralebronbn@upmc.edu

Jacob DeBerry1

Jacob DeBerry1  Sandeep Sahay

Sandeep Sahay Eduardo Bossone

Eduardo Bossone Mary Jo S. Farmer

Mary Jo S. Farmer Charles B. Ross

Charles B. Ross Belinda N. Rivera-Lebron

Belinda N. Rivera-Lebron